Abstract

Approximately 22,700 Canadian women were expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2012. Despite improvements in screening and adjuvant treatment options, a substantial number of postmenopausal women with hormone receptor positive (hr+) breast cancer will continue to develop metastatic disease during or after adjuvant endocrine therapy. Guidance on the selection of endocrine therapy for patients with hr+ disease that is negative for the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2–) and that has relapsed or progressed on earlier nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor (nsai) therapy is of increasing clinical importance. Exemestane, fulvestrant, and tamoxifen are approved therapeutic options in this context. Four phase iii trials involving 2876 patients—efect, sofea, confirm, and bolero-2—have assessed the efficacy of various treatment options in this clinical setting. Data from those trials suggest that standard-dose fulvestrant (250 mg monthly) and exemestane are of comparable efficacy, that doubling the dose of fulvestrant from 250 mg to 500 mg monthly results in a 15% reduction in the risk of progression, and that adding everolimus to exemestane (compared with exemestane alone) results in a 57% reduction in the risk of progression, albeit with increased toxicity. Multiple treatment options are now available to women with hr+ her2– advanced breast cancer recurring or progressing on earlier nsai therapy, although current clinical trial data suggest more robust clinical efficacy with everolimus plus exemestane. Consideration should be given to the patient’s age, functional status, and comorbidities during selection of an endocrine therapy, and use of a proactive everolimus safety management strategy is encouraged.

Keywords: Advanced breast cancer, endocrine therapy, mtor-inhibitor, nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, everolimus, fulvestrant, exemestane, endocrine resistance

1. INTRODUCTION

Approximately 22,700 Canadian women were expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2012, and 5100 women were expected to die of their disease1. Between 70% and 75% of breast cancers are hormone receptor–positive (hr+)2–4. Despite significant improvements in outcomes since the early 1990s, a substantial number of women with hr+ breast cancer continue to develop metastatic disease. In the advanced breast cancer (abc) setting, sequential endocrine therapy (et) is an optimal treatment strategy for women with reasonably limited and indolent disease; for rapidly progressive or symptomatic disease, chemotherapy is commonly considered optimal5,6. Aromatase inhibitors (ais) have improved abc outcomes in postmenopausal women in the adjuvant and metastatic settings and have become important options in sequential et7–9.

Despite the efficacy of et for hr+ abc, approximately 30% of women with metastatic disease will have primary resistance to et, which is commonly defined as recurrence within the first 2 years on adjuvant et or as progressive disease within 6 months of treatment initiation for advanced disease10,11. Furthermore, many patients with initial response to et will acquire secondary resistance, commonly defined as disease progression more than 6 months after et initiation11,12. While there appears to be clinical benefit in combining therapies targeted to the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2) with et in her2-positive (her2+) abc13,14, attempts at combining other receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors with et in the her2-negative (her2–) setting have met with limited success14–16, highlighting an unmet clinical need in this population.

Sequential et with selective estrogen receptor modulators, steroidal ais, and estrogen receptor downregulators remains the current standard of care for postmenopausal women with hr+ her2– abc. Considering the increased use of nonsteroidal ai (nsai) therapy in both the adjuvant and the first-line metastatic setting, the question of which et to use upon recurrence or progression during prior nsai therapy is of increasing clinical interest. Historically, high-dose estrogen and megestrol acetate—and the more established selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen—have demonstrated clinical benefit while being reasonably well-tolerated among patients with hr+ abc17–24. However, megestrol acetate and tamoxifen have not been investigated in large phase iii trials for hr+ abc disease progressing or recurring on nsai therapy and are therefore not considered in this consensus statement. Exemestane (exe), a steroidal ai, acts by binding irreversibly to the substrate binding site of aromatase, a mechanism that contrasts with the reversible binding of nsais25. Exemestane has demonstrated activity comparable to that of tamoxifen as initial therapy for hr+ metastatic disease in postmenopausal women9, is not fully cross-resistant with nsais26, and is commonly recommended as the next line of therapy after disease progression on a nsai. Unlike tamoxifen, the estrogen receptor downregulator fulvestrant is devoid of any agonist activity27. On binding to the estrogen receptor, fulvestrant induces rapid degradation of the estrogen and progesterone receptors28,29. Fulvestrant has demonstrated activity similar to that of tamoxifen when used as initial therapy for metastatic hr+ abc progressing on prior et17,30–33.

Researchers studying resistance to et in hr+ abc have sought to identify new therapeutic strategies that enhance the efficacy of ets34. A recently identified mechanism of endocrine resistance is aberrant signalling through the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase–Akt–mammalian target of rapamycin (mtor) signalling pathway35–37. Targeted inhibition of this pathway using mtor inhibitors has therefore become a key clinical research strategy in the attempt to reverse resistance to et. Three mtor inhibitors— temsirolimus, sirolimus, and everolimus (eve)—have been tested in combination with et in the treatment of hr+ abc10,38–41. Temsirolimus was not found to improve outcomes when combined with letrozole as initial therapy for women with hr+ abc38,40; however, sirolimus and eve have both demonstrated activity when combined with et in hr+ her2– patients recurring or progressing on prior et10,39.

Postmenopausal women with hr+ her2– abc recurring or progressing on nsais have an unmet clinical need. The present consensus statement weighs available phase iii evidence and clinical issues to formulate evidence-based recommendations for et in this patient population.

2. FORMULATION OF PANEL DISCUSSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The discussions and author recommendations that follow were developed in a two-step consensus development process. Authors first participated in a Web-based consensus panel discussion on September 10, 2012, to review and discuss available evidence and to formulate treatment recommendations. The second phase of the development process involved the refinement both of the consensus discussions and of the recommendations with the active involvement of all participants in the iterative manuscript development process.

3. OVERVIEW OF KEY TRIALS OF ET FOR HR+ HER2– ABC PATIENTS RESISTANT TO NSAI THERAPY

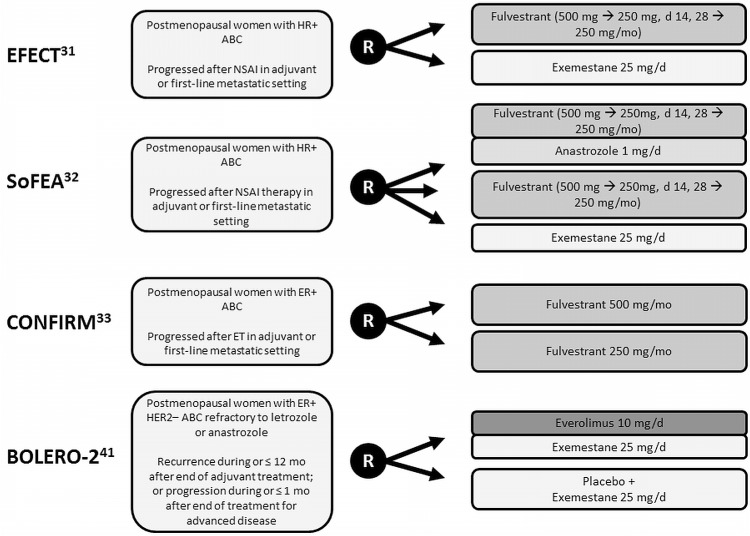

Results from four large phase iii trials evaluating et for postmenopausal patients with hr+ abc that relapsed or progressed on prior nsai therapy have been reported to date (Figure 1)31–33,41.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design summary. hr+ = hormone receptor–positive; abc = advanced breast cancer; nsai = nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor; R = randomization; er+ = estrogen receptor–positive; et = endocrine therapy; her2– = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative.

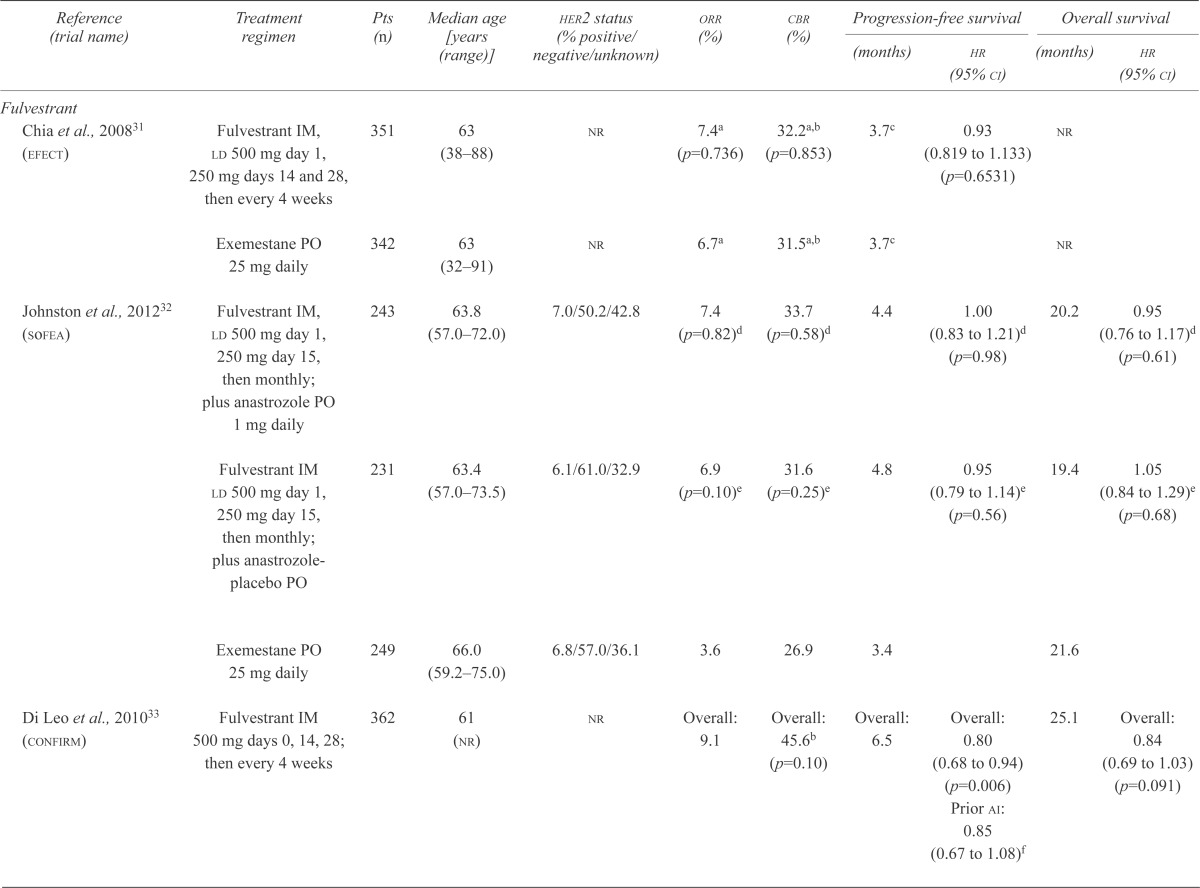

The efect trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of fulvestrant compared with exe in patients with advanced disease31. This placebo-controlled trial enrolled 693 patients and compared fulvestrant delivered intramuscularly [beginning with a loading dose of 500 mg on day 1, followed by 250 mg on days 14 and 28, and monthly thereafter (F250)] with once-daily oral exe at 25 mg (Figure 1). The primary endpoint was time to progression (ttp), and baseline patient and disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment arms. The two regimens demonstrated comparable objective response rates (orr: 7.4% and 6.7%; p = 0.74) and ttp (3.7 months in both arms, p = 0.653, Table i). Survival data have yet to be reported31.

TABLE I.

Efficacy outcomes: phase iii clinical trials of endocrine therapy for advanced breast cancer failing prior nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors

| Reference (trial name) | Treatment regimen | Pts (n) | Median age [years (range)] | her2 status (% positive/negative/unknown) | orr (%) | cbr (%) |

Progression-free survival

|

Overall survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (months) | hr (95% ci) | (months) | hr (95% ci) | |||||||

| Fulvestrant | ||||||||||

| Chia et al., 200831 (efect) | Fulvestrant IM, ld 500 mg day 1, 250 mg days 14 and 28, then every 4 weeks | 351 | 63 (38–88) | nr | 7.4a (p=0.736) | 32.2a,b (p=0.853) | 3.7c | 0.93 (0.819 to 1.133) (p=0.6531) |

nr | |

| Exemestane PO 25 mg daily | 342 | 63 (32–91) | nr | 6.7a | 31.5a,b | 3.7c | nr | |||

| Johnston et al., 201232 (sofea) | Fulvestrant IM, ld 500 mg day 1, 250 mg day 15, then monthly; plus anastrozole PO 1 mg daily | 243 | 63.8 (57.0–72.0) | 7.0/50.2/42.8 | 7.4 (p=0.82)d | 33.7 (p=0.58)d | 4.4 | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.21)d (p=0.98) |

20.2 | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.17)d (p=0.61) |

| Fulvestrant IM ld 500 mg day 1, 250 mg day 15, then monthly; plus anastrozole-placebo PO | 231 | 63.4 (57.0–73.5) | 6.1/61.0/32.9 | 6.9 (p=0.10)e | 31.6 (p=0.25)e | 4.8 | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.14)e (p=0.56) |

19.4 | 1.05 (0.84 to 1.29)e (p=0.68) |

|

| Exemestane PO 25 mg daily | 249 | 66.0 (59.2–75.0) | 6.8/57.0/36.1 | 3.6 | 26.9 | 3.4 | 21.6 | |||

| Di Leo et al., 201033 (confirm) | Fulvestrant IM 500 mg days 0, 14, 28; then every 4 weeks | 362 | 61 (nr) | nr | Overall: 9.1 | Overall: 45.6b (p=0.10) | Overall: 6.5 | Overall: 0.80 (0.68 to 0.94) (p=0.006) Prior ai: 0.85 (0.67 to 1.08)f |

25.1 | Overall: 0.84 (0.69 to 1.03) (p=0.091) |

| Fulvestrant IM 250 mg days 0 and 28, then every 4 weeks | 374 | 61 (nr) | nr | Overall: 10.2 | Overall: 39.6b | Overall: 5.5 | Overall: 22.8 | |||

| Everolimus | ||||||||||

| Baselga et al., 201241 (bolero-2) | Everolimus PO 10 mg daily, exemestane PO 25 mg daily | 485 | 62 34–93 | 9.5 (p<0.001) | 79.6 (p<0.001) | 6.9 | 0.43 (0.35 to 0.54) (p<0.001) |

nr | ||

| 0.0/100.0/0.0 | Central assessment: 10.6 | Central assessment: 0.36 (0.27 to 0.47) (p<0.001) |

||||||||

| Everolimus-placebo PO, exemestane PO 25 mg daily | 239 | 61 (28–90) | 0.4 | 59.0 | 2.8 Central assessment: 4.1 |

nr | ||||

Response-evaluable population: fulvestrant, n=270; exemestane n=270.

Clinical benefit defined as complete response plus partial response plus stable disease ≥ 24 weeks.

Time to progression.

Fulvestrant plus anastrozole versus fulvestrant plus anastrozole-placebo.

Fulvestrant plus anastrozole-placebo versus exemestane.

hr and 95% ci estimated from forest plots.

Pts = patients; her2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; orr = objective response rate; cbr = clinical benefit rate; hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval; IM = intramuscular injection; ld = loading dose; nr = not reported; PO = oral.

The sofea trial compared both fulvestrant alone and fulvestrant plus anastrozole with exe. This threearm trial accrued 750 hr+ patients and compared an intramuscular injection of fulvestrant [beginning with a loading dose of 500 mg, followed by 250 mg on day 15, and monthly thereafter (F250)] plus an oral daily dose of anastrozole 1 mg with F250 plus placebo and with an oral daily dose of exe 25 mg (Figure 1)32. Baseline patient and disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment arms, and the primary endpoint was progression-free survival (pfs). Compared with exe, neither F250 alone nor F250 combined with anastrozole resulted in a significantly improved orr (6.9% vs. 7.4% vs. 3.6%), pfs (4.8 months vs. 4.4 months vs. 3.4 months), or overall survival (os: 19.4 months vs. 20.2 months vs. 21.6 months; Table i).

In both the foregoing trials, F250 and exe were well tolerated, with low rates of treatment discontinuation because of toxicity and low rates of serious adverse events. The most common adverse events of any grade for the sofea trial were nausea (43.5% F250 vs. 37.2% exe), arthralgia (42.6% vs. 46.6%), and lethargy (62.6% vs. 54.3%, Table ii).

TABLE II.

Summary of adverse events of any grade reported at 40% or more frequentlya in phase iii endocrine therapy trials

| Adverse event | Reference (study name) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chia et al., 200831 (efect) | Johnston et al., 201232 (sofea) | Di Leo et al., 201033 (confirm) |

Baselga et al., 201241 Hortobagyi et al., 201142 (bolero-2) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Ful (n=351) | Exe (n=340) | Ful (n=230) | Exe (n=247) | F500 (n=361) | F250 (n=374) | Eve plus Exe (n=482) | Pbo plus Exe (n=238) | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Anyb (%) | Anyb (%) | Any (%) | Grades 3 and 4 (%) | Any (%) | Grades 3 and 4 (%) | Anyc (%) | Grades 3 and 4d (%) | Anyc (%) | Grades 3 and 4d (%) | Any (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Grade 4 (%) | Any (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Grade 4 (%) | |

| Stomatitis | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | 56 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | 50 | 4 | 2 | 25 | 2 | 0 |

| Nausea | 6.8 | 7.9 | 43.5e | 0.9e | 37.2e | 3.2e | nr | nr | nr | nr | 27 | <1 | <1 | 27 | 1 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 3.7 | 5.6 | 42.6 | 3.0 | 46.6 | 3.2 | 18.8f | 2.2f | 18.7f | 2.1f | 16 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Lethargy | 3.1g | 2.1g | 62.6 | 4.8 | 54.3 | 4.5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

Adverse events reported at 40% or more often (all grades) in one or more of the included trials; rates of those adverse events are given across all trials, even if less than 40% incidence.

Adverse events with more than 2% incidence.

Grades 1–4.

Grade 3 or higher.

Nausea or vomiting.

Joint disorders.

Asthenia.

Ful = fulvestrant; Exe = exemestane; F500 = fulvestrant 500 mg; F250 = fulvestrant 250 mg; Eve = everolimus; Pbo = placebo; nr = not reported.

The phase iii double-blind placebo-controlled confirm trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of doubling the dose of fulvestrant for patients with prior exposure to et33. A total of 736 patients with recurrent or progressive disease on either prior ai therapy (42.5%) or prior anti-estrogen therapy (57.5%) were enrolled in the trial. Patients were randomized to receive an intramuscular dose of fulvestrant either 500 mg or 250 mg monthly (F500 vs. F250, Figure 1). The primary endpoint was pfs. Baseline patient and disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment arms. Doubling the dose of fulvestrant did not improve the orr (9.1% F500 vs. 10.2% F250, p = 0.795) or os (25.1 months vs. 22.8 months, p = 0.91, Table i). Patients receiving the higher dose of fulvestrant experienced a statistically significant improvement in median pfs [6.5 months vs. 5.5 months; hazard ratio (hr): 0.80; 95% confidence interval (ci): 0.68 to 0.94; p = 0.006], which trended toward significance in patients recurring or progressing on prior ais (estimated hr: 0.85; 95% ci: 0.67 to 1.08). No substantial differences in the incidence or severity of adverse events were observed in the two arms. With F500, no adverse events with an overall incidence of 40% or greater were observed (Table ii). Although F500 is clearly superior to F250, the optimal dose and schedule of fulvestrant remains unclear43,44.

The placebo-controlled phase iii bolero-2 trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of adding eve to exe in this patient population41. A total of 724 patients were randomized 2:1 to either a daily oral dose of eve 10 mg and exe 25 mg or to placebo and exe (Figure 1). The primary endpoint was investigator-assessed pfs. Baseline patient and disease characteristics were balanced between the treatment arms. Results of the primary analysis demonstrated statistically significant improvements in orr and in both the investigator-assessed and the centrally-reviewed pfs favouring the experimental arm (Table i). Updated outcomes reported at a median follow-up of 18 months confirmed significant improvements in orr (12.6% vs. 1.7%, p < 0.0001) and investigator-assessed median pfs (7.8 months vs. 3.2 months; hr: 0.45; 95% ci: 0.38 to 0.54; p < 0.0001) favouring the addition of eve to exe45. Fewer deaths were reported in the eve plus exe arm (os events: 25.4% vs. 32.2%)45, although os results remain immature at the time of writing. Adverse events observed in the eve plus exe arm were consistent with those reported in other studies, with increased toxicity observed for the addition of eve to exe41. Stomatitis and infection were the most common adverse events associated with eve plus exe (grade 3 or 4: 8% eve+exe vs. 1% placebo+exe, and 6% vs. 2%; any grade: 56% vs. 11%, and 50% vs. 25%; Table ii).

4. PANEL DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

4.1. Management of Postmenopausal Patients with HR+ HER2– ABC Recurring or Progressing on Prior NSAI Therapy

4.1.1. Discussion

In first- and second-line treatment of abc, pfs and os are both important measures of clinical benefit. However, clinical trials are often underpowered to effectively evaluate os as a primary endpoint in the endocrine-sensitive abc patient population because of sequential treatment options and the protracted post-progression survival interval, which often confound detection of et-related os benefits46. Determining whether, in this clinical setting, nonsignificant os differences are a result of limitations in trial design or a true measure of lack of os benefit is therefore difficult. As a result, pfs as a primary endpoint is gaining importance in first- and second-line settings. However, pfs is often considered a less reliable measure, being more complex and possibly more susceptible to bias and error. Results from trials that control for investigator bias through the use of a double-blind trial design and independent review assessment are therefore considered more reliable46.

Four clinical trials have assessed the benefit of et therapy in postmenopausal women with hr+ disease recurring or progressing on prior nsai therapy. In all four trials, investigator-assessed pfs was the primary endpoint, and two of them—the confirm and bolero-2 trials—reported statistically significant improvements in pfs. Both trials used a double-blind design to control for investigator bias, and the bolero-2 results were also independently assessed.

In the confirm trial, patients receiving a higher dose of fulvestrant (F500 compared with F250) experienced a 20% reduction in the risk of progression (hr: 0.80; 95% ci: 0.68 to 0.94) and an incremental gain in median pfs of 1.0 month (6.5 months vs. 5.5 months, p = 0.006). In the bolero-2 trial, patients receiving eve plus exe experienced a reduction in the risk of progression of between 57% and 64% (locally assessed hr: 0.43; 95% ci: 0.35 to 0.54; centrally assessed hr: 0.36; 95% ci: 0.27 to 0.47) and a net gain in median pfs of between 4.1 and 6.5 months (locally assessed: 6.9 months vs. 2.8 months, p < 0.001; centrally assessed: 10.6 months vs. 4.1 months, p < 0.001)41. At a median follow-up of 18 months, the os data remained immature45.

Subgroup analyses are used to identify treatment effects i n s pecific p opulations, b ut t hey a re o ften limited in statistical power and may be susceptible to bias related to imbalances in patient or disease characteristics between treatment arms. Investigators conducting the confirm and bolero-2 trials carried out preplanned subgroup analyses based on endocrine sensitivity, burden of disease, and age. Patients in the confirm trial were stratified based on institutional affiliation, and patients in the bolero-2 trial were stratified according to the presence or absence of visceral disease and endocrine sensitivity. In confirm, a statistically significant pfs benefit favouring F500 was observed in patients demonstrating resistance to prior et therapy and in those without visceral disease. Robust statistically significant effects were seen in all subgroups in the bolero-2 trial, regardless of burden of disease, endocrine sensitivity, and age.

In both the confirm and bolero-2 trials, most patients were described as having endocrine-sensitive disease (63%–67% and 84% respectively), defined as disease recurrence lasting at least 2 years after initiation of adjuvant et or progression after more than 6 months on et for advanced disease33,41. Subgroup analyses were conducted for endocrine-sensitive patients in both trials. Overall benefits for eve plus exe were confirmed in the subpopulation of 610 endocrine-sensitive patients (estimated hr: 0.43; 95% ci: 0.34 to 0.54; Table iii). The overall benefits of F500 were not statistically significant in the endocrine-sensitive population (estimated hr: 0.86; 95% ci: 0.72 to 1.05), but the results are likely similar to those observed in the overall population.

TABLE III.

Phase iii subgroup outcomes by degree of sensitivity to prior endocrine therapy

| Reference (study name) | Regimen | Prior et |

Sensitivity to prior

et

|

Progression-free survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Proportion (%) | Prior sensitivity | Prior resistance | |||

| Fulvestrant | ||||||

| Chia et al., 200831 (efect) | Fulvestrant 250 mg vs. exemestane | nsai | ≥6 Months before recurrence or progression | 61–64 |

hr: 0.90 (95% ci: 0.73 to 1.08)a (ttp, n=434) |

hr: 1.01 (95% ci: 0.79 to 1.35)a (ttp, n=259) |

| Johnston et al., 201232 (sofea) | Fulvestrant 250 mg vs. exemestane | nsai | >1 Year before progression | 1–2 Years: 26–35 >2 Years: 27–31 |

hr: 0.75 (95% ci: 0.54 to 1.06) (1–2 years, n=149)b hr: 1.06 (95% ci: 0.75 to 1.50) (>2 years, n=139)b |

hr: 1.27 (95% ci: 0.84 to 1.91)c (n=100) |

| Di Leo et al., 201033 (confirm) | Fulvestrant 500 mg vs. fulvestrant 250 mg | Tamoxifen or ai | >2 Years before recurrence ≥6 Months before progression |

63–67 |

hr: 0.86 (95% ci: 0.72 to 1.05)a |

hr: 0.72 (95% ci: 0.57 to 0.93)a,d |

| Everolimus | ||||||

| Baselga et al., 201241 (bolero-2) | Everolimus plus exemestane vs. exemestane | nsai | ≥2 Years before recurrence ≥6 Months before progression |

84 |

hr: 0.43 (95% ci: 0.34 to 0.54)a (n= 610) |

hr: 0.49 (95% ci: 0.30 to 0.81)a (n=114) |

hr and 95% ci estimated from forest plots.

Does not include patients receiving nsais in the adjuvant setting.

Locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer and less than 1 year on nsai therapy.

Poorly responsive or status unknown.

et = endocrine therapy; nsai = nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor; hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval; ttp = time to progression; ai = aromatase inhibitor.

A substantial proportion of patients in both the confirm and bolero-2 trials lacked visceral involvement (approximately 45%)33,41. Patients without visceral disease receiving F500 in the confirm trial experienced a 25% reduction in the risk of progression compared with patients receiving F250 (estimated hr: 0.75; 95% ci: 0.57 to 0.95); patients without visceral involvement receiving eve plus exe in the bolero-2 trial experienced a 59% reduction in the risk of progressive disease (9.9 months vs. 4.2 months; hr: 0.41; estimated 95% ci: 0.30 to 0.56; Table iv)45. The benefit of eve plus exe was pronounced in patients with bone-only disease; those patients experienced a 67% reduction in the risk of progression and a net median pfs gain of 7.6 months (12.9 months vs. 5.3 months; hr: 0.33; estimated 95% ci: 0.20 to 0.55) compared with those receiving placebo plus exe45. It is notable that exe alone increased bone turnover and that the addition of eve reversed the exe-induced increase in bone resorption and appears to have contributed to a significant reduction in the cumulative incidence of disease progression from bone metastases in patients receiving eve plus exe compared with those receiving placebo plus exe (p = 0.036)47.

TABLE IV.

Phase iii subgroup outcomes by burden of disease

| Reference (study name) | Regimen | Visceral disease (%) | orra (%) |

Progression-free survival by visceral disease status

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Fulvestrant | |||||

| Chia et al., 200831 (efect) | Fulvestrant 250 mg vs. exemestane | 57.0 | 7.4 vs. 6.7 (p=0.736) |

hr: 0.89 (95% ci: 0.75 to 1.10)b (ttp, n=395) |

hr: 1.00 (95% ci: 0.80 to 1.35)b (ttp, n=298) |

| Johnston et al., 201232 (sofea) | Fulvestrant 250 mg vs. exemestane | Visceral: 60.0 Soft tissue or node: 25.2 Bone: 14.4 |

6.9 vs. 3.6 (p=0.10) |

hr: 0.93 (95% ci: 0.73 to 1.18) (viscera dominant site of relapse, n=288) |

hr: 0.79 (95% ci: 0.54 to 1.16) (soft tissue or node, n=121) hr: 1.37 (95% ci: 0.83 to 2.25) (bone, n=69) |

| Di Leo et al., 201033 (confirm) | Fulvestrant 500 mg vs. fulvestrant 250 mg | 54.8 | 9.1 vs. 10.2 |

hr: 0.80 (95% ci: 0.65 to 1.00)b (n=471) |

hr: 0.75 (95% ci: 0.57 to 0.95)b (n=265) |

| Everolimus | |||||

| Piccart et al., 201245 (bolero-2) | Everolimus plus exemestane vs. exemestane | 56 | 12.6 vs. 1.7 (p<0.0001) |

6.8 vs. 2.8 months hr: 0.47 (95% ci: 0.38 to 0.60)b (n=406) |

9.9 vs. 4.2 months hr: 0.41 (95% ci: 0.30 to 0.56)b (n=318) |

Response rates for overall population.

hr and 95% ci estimated from forest plot.

orr = objective response rate; hr = hazard ratio; ci = confidence interval; ttp = time to progression.

No significant differences in the incidence or severity of adverse events were observed between F500 and F250 in the confirm trial. However, higher rates of trial discontinuation for toxicity were observed when eve was added to exe (19% vs. 4%), with increased rates of serious adverse events attributable to treatment (11% eve+exe vs. 1% placebo+exe) and a slightly higher proportion of deaths attributable to adverse events (1% vs. <1%)41. However, despite those differences, quality of life was not compromised for patients receiving eve plus exe compared with those receiving placebo plus exe (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer qlq–C30 Global Health Status—Time to Definitive Deterioration minimally important difference: 5% change from baseline, 8.3 months vs. 5.8 months, p = 0.0084; 10% change from baseline, 11.7 months vs. 8.4 months, p = 0.1017)48.

4.1.2. Recommendation

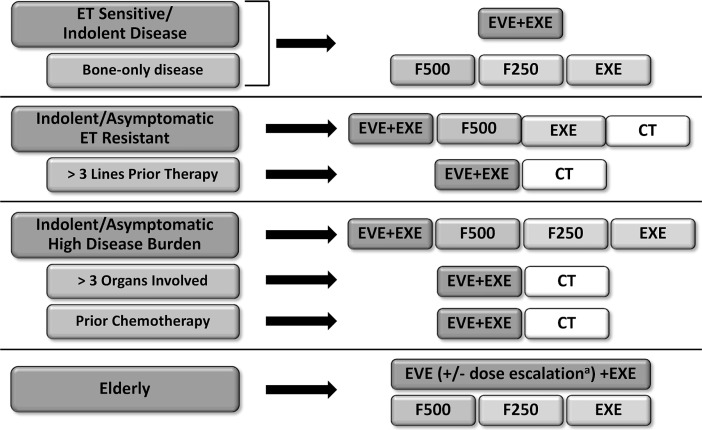

Multiple treatment options are available to women with hr+ her2– abc recurring or progressing on prior nsai therapy, including exe, F250, F500, and eve plus exe31–33,41. When considering et, thought should be given to disease extent, degree of symptomatology, and duration of clinical benefit on prior et. For patients with relatively indolent progression and endocrine-sensitive disease for whom et is indicated, the available evidence supports the use of eve plus exe, which may be of particular benefit for patients with bone-only disease. But this combination may not be ideal for all patients; when selecting et, consideration should be given to patient age, functional status, and extent of comorbidities. Other et options should be considered in the event that a patient is unable to tolerate eve.

Because of the increased risk of serious adverse events with the addition of eve to exe, together with the potential for early onset of select adverse events, careful proactive safety monitoring and toxicity management is strongly recommended for patients on eve plus exe, so as to maximize clinical benefit and treatment adherence49. For appropriate patients, eve should begin at the prescribed dose of 10 mg, with a first follow-up appointment within 2 weeks to ensure early detection of hematologic or pulmonary adverse events, oral mucositis, or fatigue. Patients should undergo regular monthly clinical monitoring, including functional inquiry and symptom-directed physical examination, complete blood count and glucose level, and disease imaging every 3 months. For grade 3 adverse events, treatment may be interrupted until resolution and then resumed at the same or a lower dose. In the event of symptomatic pneumonitis, infection should be ruled out, treatment interrupted, and oral corticosteroids administered until symptoms resolve. Resolution may take between 7–10 days, at which point eve may be reinitiated at a lower dose. Treatment should be discontinued in the event of grade 4 adverse events. If a patient is unable to tolerate eve plus exe, treatment with F500 or exe is also an option.

4.2. Management of ET-Resistant Disease

4.2.1. Discussion

Although fewer in number, endocrine-resistant patients were represented in both the confirm (33%–37%) and the bolero-2 (16%) trials33,41. Compared with endocrine-resistant patients receiving F250 in the confirm trial, those receiving F500 experienced a 28% reduction in the risk of progression (estimated hr: 0.72; 95% ci: 0.57 to 0.93), and in the bolero-2 trial, compared with patients receiving placebo plus exe, those receiving eve plus exe experienced a 51% reduction in the risk of progression (estimated hr: 0.49; 95% ci: 0.30 to 0.81; Table iii). The benefits of eve plus exe extended to patients receiving 3 or more lines of prior systemic therapy. These heavily pretreated patients experienced a 59% reduction in the risk of progression (hr: 0.41; estimated 95% ci: 0.32 to 0.53) and incremental median pfs gains of 5.2 months (8.2 months vs. 3.0 months)45.

4.2.2. Recommendation

Treatment options in women with hr+ her2– abc recurring or progressing on prior nsai therapy who have relatively indolent progression and resistant disease are limited to F500, eve plus exe, chemotherapy, and exe31–33,41. For those patients, the magnitude of the clinical benefit, balanced with tolerability and convenience relative to chemotherapy, support the use of eve plus exe regardless of prior therapies. Chemotherapy remains the recommended treatment choice for patients with symptomatic visceral disease. Because eve plus exe may not be ideal for all patients, consideration should be given to the patient’s age, functional status, and comorbidities, and alternative et options should be considered if a patient is unable to tolerate eve. A proactive eve safety management strategy is recommended, and for patients for whom eve plus exe is not well tolerated, treatment with F500, exe alone, or chemotherapy should be considered.

4.3. Treatment of Patients with High Burden of Disease

4.3.1. Discussion

Endocrine therapy is the preferred option for hr+ abc, even in the presence of visceral disease6, and chemotherapy is recommended for patients with rapidly progressive or symptomatic visceral disease5,6. More than half the patients in both the confirm and the bolero-2 trials had visceral disease (55%–56%). Among patients with visceral disease in the confirm trial, those receiving F500 (compared with those receiving F250) experienced a 20% reduction in the risk of progression (estimated hr: 0.80; 95% ci: 0.65 to 1.00)33, and in the bolero-2 trial, compared to those receiving placebo plus exe, those receiving eve plus exe experienced a 53% reduction in the risk of progression (pfs: 6.8 months vs. 2.8 months; hr: 0.47; estimated 95% ci: 0.38 to 0.60)45 and a significantly improved orr (9.5% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001) overall41. Additionally, at a median follow-up of 18 months, patients with extensive visceral involvement and those who had received prior chemotherapy both experienced a 59% reduction in the risk of progression (>3 organs involved: 6.9 months vs. 2.6 months; hr: 0.41; estimated 95% ci: 0.30 to 0.55; prior chemotherapy: 8.2 months vs. 3.2 months; hr: 0.41; estimated 95% ci: 0.33 to 0.52)45.

4.3.2. Recommendation

Chemotherapy is recommended for women with hr+ her2– abc with symptomatic or rapidly progressive disease5,6. For patients with more indolent visceral disease or those declining chemotherapy, a number of treatment options, including exe, F250, F500, and eve plus exe are available31–33,41. The strength of the evidence and the magnitude of clinical benefit observed in bolero-2 supports the use of eve plus exe in patients with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic visceral disease, regardless of disease extent and receipt of prior chemotherapy. A proactive eve safety management strategy is recommended, and for those in whom eve plus exe is not well-tolerated, treatment with F500, exe, or chemotherapy should be considered.

4.4. Treatment of Elderly Patients with HR+ Disease Refractory to NSAIs

4.4.1. Discussion

Elderly patients are more likely to have multiple comorbidities that may limit life expectancy or tolerance of therapies50. A comprehensive geriatric assessment is an important component in the decision to pursue systemic therapies. A substantial proportion of patients in both the confirm and bolero-2 trials were 65 years of age or older (median: 61 years and 61–62 years respectively), and preplanned subgroup analyses in elderly populations were conducted for both trials. In the confirm trial, elderly patients receiving F500 (compared with those receiving F250) experienced a 14% reduction in the risk of progression (hr: 0.86; 95% ci: 0.67 to 1.09) and no observed increase in the rate of adverse events. At 18 months’ follow-up, patients receiving eve plus exe in the bolero-2 trial experienced a 41% (for those 65 years of age or older) and a 55% reduction in the risk of progression (for those 70 years of age or older)51. The most common adverse events in elderly patients were stomatitis, fatigue, decreased appetite, and diarrhea. Treatment with eve was also associated with a greater incidence of on-treatment death in elderly women than in younger patients (Pritchard K. Unpublished data, November 2012). Most of the deaths were reported in very elderly patients (70 years of age and older) and might have been associated with comorbidities and overall health status at study entry.

4.4.2. Recommendation

Many treatment options are available to elderly post-menopausal hr+ her2– patients who have recurrent or progressive disease on prior nsai therapy, including exe, F250, F500, and eve plus exe31–33,41. Clinical judgment should be used when selecting an et, and elderly patients should be well informed about the need for early toxicity reporting. Current evidence supports use of eve plus exe in conjunction with thorough and proactive adverse event management. In very elderly patients or in those with comorbidities or compromised health status, a dose escalation strategy should be considered, beginning with a starting dose of 5 mg and slowly increasing to a dose of 10 mg with demonstrated tolerance. In the event that an elderly patient is unable to tolerate eve plus exe, the use of F500 or another et regimen is encouraged.

5. RE-BIOPSY

5.1. Discussion

There is evidence that receptor status may change over time and over the course of treatment. Guidelines from the Advanced Breast Cancer First International Consensus Conference therefore recommend biopsy of a metastatic lesion, if easily accessible, to confirm diagnosis and to evaluate hormone receptor and her2 expression52,53. In the context of hr+ her2– disease, a previously her2– tumour may be found to be her2+ upon re-biopsy, which would increase the number of treatment options by adding her2-targeted therapies. In contrast, discovery of a change from hr+ to hr– potentially suggests resistance to et and a need to try alternative therapies. Regardless of findings, re-biopsy results should be interpreted with caution and within the context of the patient’s unique disease and treatment history, because variations in tissue processing and sampling can produce erroneous results.

5.2. Recommendation

The re-biopsy of a tumour once over the course of treatment for advanced disease is a reasonable practice if sample collection is straightforward and does not pose undue risk to the patient. Re-biopsy is strongly encouraged in women whose disease is not following the expected pattern of progression based on tumour receptor profile or in the case of an isolated lesion. Caution should be used when interpreting re-biopsy results, especially in instances in which loss of receptor status expression might result in the withholding of targeted therapy.

6. SUMMARY

With the increased use of nsai therapy in both the adjuvant and first-line settings, there is a need to identify the optimal sequencing of et in women with hr+ her2– abc who have recurrent or progressive disease on nsai therapy. Sequential et remains the goal of treatment for these patients5. Four large phase iii trials—efect, sofea, confirm, and bolero-2—assessed the benefits of particular et regimens in this patient population31–33,41. Those studies demonstrated that F250 and exe are of comparable efficacy and that, compared with fulvestrant alone, the addition of anastrozole to fulvestrant does not improve outcomes. Data also demonstrate that F500 and eve plus exe result in statistically significant improvements in pfs compared with control regimens, with associated reductions of 20% and 57% respectively in the risk of progression. Increasing the dose of fulvestrant from F250 to F500 did not increase toxicity, but an increase in toxicity was seen with the addition of eve to exe. Of the many available et options for patients with hr+ her2– disease who have experienced disease recurrence or progression on prior nsai therapy, the rigour of the evidence and the magnitude of the clinical benefit support the use of eve plus exe in most clinical cohorts (Figure 2). Consideration should be given to the patient’s age, functional status, and comorbidities when selecting an et, and use of a proactive eve safety management strategy is encouraged.

FIGURE 2.

Endocrine therapy (et) treatment guidelines for postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer recurring or progressing on prior nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy. a For patients 70 years of age or older, or for those with multiple comorbidities or frailties compromising overall health status, consideration should be given to a reduced starting dose of 5 mg daily, followed by potential dose escalation based on tolerance. eve = everolimus; exe = exemestane; F500 = fulvestrant 500 mg; F250 = fulvestrant 250 mg; ct = chemotherapy.

7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Loretta Collins of Kaleidoscope Strategic for her editorial assistance in preparing the review and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. for the unrestricted educational grant that funded Kaleidoscope Strategic’s editorial and support services.

8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

KIP is a consultant for Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abraxis, Pfizer, and Amgen, and has received honoraria from Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abraxis, Pfizer, Boehringer–Ingelheim, and Amgen. KAG is a consultant for Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Amgen, and has received research funding from Roche. LP is a consultant for Roche and Novartis. She has received honoraria from Roche, Novartis, and Amgen, and research funding from Roche and Pfizer. DR is a consultant for Roche and Novartis, has received honoraria from Roche and Novartis, and has received research funding from Roche. MW is a consultant for Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca, and has received honoraria from Novartis, Astra-Zeneca, and Roche. DM is owner and founder of Kaleidoscope Strategic. SV is a consultant for Novartis, AstraZeneca, Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline, has received honoraria from Novartis, Astra Zeneca, and Roche, and has received research funding from Roche and Sanofi-Aventis.

Support for the preparation of the consensus panel discussion and development of the manuscript was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. Authors received honoraria for participation in the consensus panel discussion, but no remuneration was provided for development of the consensus manuscript.

9. REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society . Breast Cancer Statistics at a Glance [Web page] Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2012. [Available at: http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/About%20cancer/Cancer%20statistics/Stats%20at%20a%20glance/Breast%20cancer.aspx?sc_lang=EN; cited September 27, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennecke HF, Ellard S, O’Reilly S, Gelmon KA. New guidelines for treatment of early hormone-positive breast cancer with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors. BC Med J. 2006;48:121–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villarreal–Garza C, Cortes J, Andre F, Verma S. mtor inhibitors in the management of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the latest evidence and future directions. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2526–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang HJ, Neven P, Drijkoningen M, et al. Association between tumour characteristics and her-2/neu by immunohistochemistry in 1362 women with primary operable breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:611–16. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.022772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) Breast Cancer. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2012. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Ver 3.2012. [Available online at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (free registration required); cited September 16, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, et al. 1st International consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (abc 1) Breast. 2012;21:242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonneterre J, Buzdar A, Nabholtz JM, et al. Anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen as first-line therapy in hormone receptor positive advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:2247–58. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2247::AID-CNCR1570>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, et al. Superior efficacy of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: results of a phase iii study of the International Letrozole Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2596–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paridaens RJ, Dirix LY, Beex LV, et al. Phase iii study comparing exemestane with tamoxifen as first-line hormonal treatment of metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4883–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. Randomized phase ii trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a gineco study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2718–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedard PL, Freedman OC, Howell A, Clemons M. Overcoming endocrine resistance in breast cancer: are signal transduction inhibitors the answer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:307–17. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, et al. tamrad: a gineco randomized phase ii trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone in patients (pts) with hormone-receptor positive, her2 negative metastatic breast cancer (mbc) with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors (ai) [abstract S1–6]. Presented at the 33rd Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 8–12, 2010; San Antonio, TX. [Available online at: http://www.abstracts2view.com/sabcs10/view.php?nu=SABCS10L_230&terms=; cited September 28, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman B, Mackey JR, Clemens MR, et al. Trastuzumab plus anastrozole versus anastrozole alone for the treatment of postmenopausal women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive, hormone receptor–positive metastatic breast cancer: results from the randomized phase iii tandem study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5529–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartzberg LS, Franco SX, Florance A, O’Rourke L, Maltzman J, Johnston S. Lapatinib plus letrozole as first-line therapy for her-2+ hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:122–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cristofanilli M, Valero V, Mangalik A, et al. Phase ii, randomized trial to compare anastrozole combined with gefitinib or placebo in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1904–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osborne CK, Neven P, Dirix LY, et al. Gefitinib or placebo in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: a randomized phase ii study. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1147–59. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell A, Robertson JF, Quaresma Albano J, et al. Fulvestrant, formerly ici 182,780, is as effective as anastrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer progressing after prior endocrine treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3396–403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingle JN, Ahmann DL, Green SJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of diethylstilbestrol versus tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:16–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101013040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allegra JC, Bertino J, Bonomi P, et al. Metastatic breast cancer: preliminary results with oral hormonal therapy. Semin Oncol. 1985;12:61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill PG, Gebski V, Snyder R, et al. Randomized comparison of the effects of tamoxifen, megestrol acetate, or tamoxifen plus megestrol acetate on treatment response and survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:741–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingle JN, Ahmann DL, Green SJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of megestrol acetate versus tamoxifen in paramenopausal or castrated women with advanced breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:155–60. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198204000-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan LR. Megestrol acetate v tamoxifen in advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal patients. Semin Oncol. 1985;12:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muss HB, Wells HB, Paschold EH, et al. Megestrol acetate versus tamoxifen in advanced breast cancer: 5-year analysis—a phase iii trial of the Piedmont Oncology Association. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1098–106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.7.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paterson AH, Hanson J, Pritchard KI, et al. Comparison of antiestrogen and progestogen therapy for initial treatment and consequences of their combination for second-line treatment of recurrent breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1990;17:52–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller WR, Bartlett J, Brodie AM, et al. Aromatase inhibitors: are there differences between steroidal and nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors and do they matter? Oncologist. 2008;13:829–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonning PE. Lack of complete cross-resistance between different aromatase inhibitors; a real finding in search for an explanation? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakeling AE, Dukes M, Bowler J. A potent specific pure anti-estrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3867–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeFriend DJ, Howell A, Nicholson RI, et al. Investigation of a new pure antiestrogen (ici 182780) in women with primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:408–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson JF, Nicholson RI, Bundred NJ, et al. Comparison of the short-term biological effects of 7alpha-[9-(4,4,5,5,5-pentafluoropentylsulfinyl)-nonyl]estra-1,3,5, (10)-triene-3,17beta-diol (Faslodex) versus tamoxifen in postmeno-pausal women with primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6739–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howell A, Robertson JF, Abram P, et al. Comparison of fulvestrant versus tamoxifen for the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women previously untreated with endocrine therapy: a multinational, double-blind, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1605–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chia S, Gradishar W, Mauriac L, et al. Double-blind, randomized placebo controlled trial of fulvestrant compared with exemestane after prior nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor therapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, advanced breast cancer: results from efect. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1664–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston S, Kilburn LS, Ellis P, et al. Fulvestrant alone or with concomitant anastrozole vs. exemestane following progression on non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor—first results of the sofea trial (cruke/03/021 and cruk/09/007) (isrctn44195747) [abstract LBA2] Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(suppl 3):S2. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(12)70687-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Leo A, Jerusalem G, Petruzelka L, et al. Results of the confirm phase iii trial comparing fulvestrant 250 mg with fulvestrant 500 mg in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4594–600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston SR. New strategies in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1979–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burstein HJ. Novel agents and future directions for refractory breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(suppl 2):S17–24. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston SR. Clinical efforts to combine endocrine agents with targeted therapies against epidermal growth factor receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and mammalian target of rapamycin in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1061s–8s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiff R, Massarweh SA, Shou J, Bharwani L, Mohsin SK, Osborne CK. Cross-talk between estrogen receptor and growth factor pathways as a molecular target for overcoming endocrine resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:331S–6S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-031212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baselga J, Roche H, Fumoleau P. Treatment of postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer with letrozole alone or in combination with temsirolimus: a randomized, 3-arm, phase 2 study [abstract 1068] Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94(suppl 1):S62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhattacharyya GS, Biswas J, Singh JK, et al. Reversal of tamoxifen resistance (hormone resistance) by addition of sirolimus (mtor inhibitor) in metastatic breast cancer [abstract 16LBA] Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(suppl 2):9. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70115-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow L, Sun Y, Jassem J, et al. Phase 3 study of temsirolimus with letrozole or letrozole alone in postmenopausal women with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer [abstract 6091] Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100(suppl 1):S286. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hortobagyi GN, Piccart M, Rugo H, et al. Everolimus for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: updated results of the bolero-2 phase iii trial [abstract S3–7]. Presented at the 34th Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio, TX. December 6–9, 2011; [Available online at: http://www.abstracts2view.com/sabcs11/view.php?nu=SABCS11L_1653; cited November 15, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaniklidis C. Fulvestrant loading, tumor markers, and ongoing trials. Comm Oncol. 2007;4:649–50. doi: 10.1016/S1548-5315(11)70154-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young OE, Renshaw L, Macaskill EJ, et al. Effects of fulvestrant 750 mg in premenopausal women with oestrogen-receptor-positive primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piccart M, Noguchi S, Pritchard K, et al. Everolimus for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: updated results of the bolero-2 phase iii trial [abstract 559] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=114&abstractID=101092; cited November 1, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma S, McLeod D, Batist G, Robidoux A, Martins IR, Mackey JR. In the end what matters most? A review of clinical endpoints in advanced breast cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16:25–35. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gnant M, Baselga J, Rugo HS, et al. Effects of everolimus on disease progression in bone and bone markers in patients with bone metastases [abstract 512] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=114&abstractID=100783; cited December 20, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beck JT, Rugo HS, Burris HA, et al. bolero-2: health-related quality-of-life in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with everolimus and exemestane versus exemestane [abstract 539] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=114&abstractID=101451; cited November 8, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK, Carpentier MY, Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:459–78. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson RW, Moench S, Hurria A, et al. nccn Task Force Report: breast cancer in the older woman. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(suppl 4):S1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pritchard KI, Burris HA, Rugo HS, et al. Safety of everolimus for women over 65 years of age with advanced breast cancer (bc): 12.5-mo follow-up of bolero-2 [abstract 551] J Clin Oncol. 201230 [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=114&abstractID=101036; cited November 15, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amir E, Miller N, Geddie W, et al. Prospective study evaluating the impact of tissue confirmation of metastatic disease in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:587–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindstrom LS, Karlsson E, Wilking UM, et al. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2601–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]