Abstract

Although primary liver cancer is rare, its incidence rate has been rising quickly in Canada, more than tripling since the early 1980s. This cancer is more common in men than women, and the age-specific incidence rates in men have been increasing significantly in all age groups from 40 years of age onward. The death rate has followed a similar upward trajectory, in part because of the low 5-year survival rate of 18% in both sexes. Infection with the hepatitis B or C virus continues to be the most common risk factor, but other factors may also play a role. Risk reduction strategies, such as viral hepatitis screening, have been recommended in other countries and warrant consideration in Canada as part of a coordinated strategy of disease prevention and control.

Keywords: Liver cancer, surveillance, risk factors, trends, prevention

1. INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer originates in the bile ducts, blood vessels, or connective tissue of the liver. Worldwide, this cancer is the fifth most common among men and the seventh most common among women1. Primary liver cancer remains relatively uncommon in Canada, accounting for an estimated 1% of all new cancer diagnoses and deaths in 2012, but it is a rising cause of cancer-related deaths and liver transplants. We used data from the Canadian Cancer Registry to examine the incidence and mortality trends for primary liver cancer between 1980 and 2007.

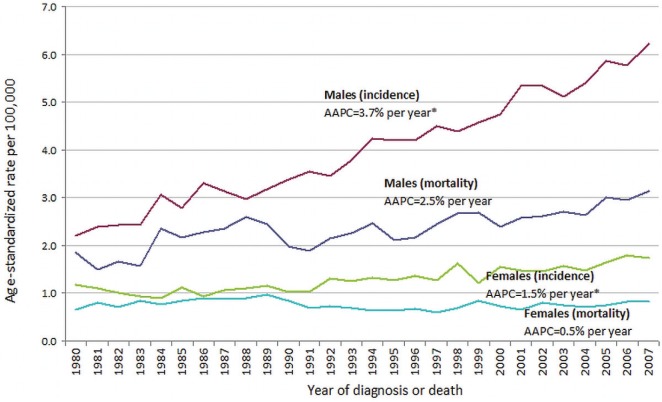

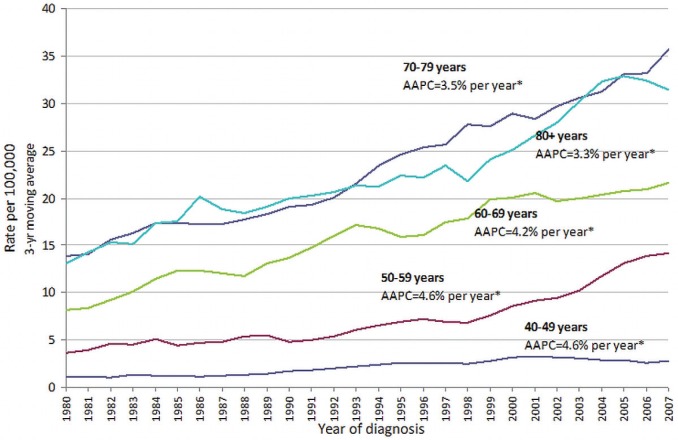

Our review shows that incidence and mortality rates have increased substantially in Canada since the early 1980s (Figure 1), particularly for hepatocellular carcinoma (hcc), which is the predominant histologic type4, comprising about 70% of new cases. The incidence rate is higher in men than in women, and in men, it tripled to 6.8 from 2.2 per 100,000 between 1980 and 20075 and is projected to increase into the future6. An examination of age-specific incidence rates in men shows the highest incidence occurring among those 70–79 years of age, although statistically significant rate increases have occurred in all age groups examined (that is, 40+ years) since 1980 (Figure 2). The death rate has followed a similar upward trajectory, reflecting the poor prognosis with this cancer and the late-stage at which it is commonly detected7. The 5-year relative survival in all stages of the disease is currently only 18% in Canada8.

FIGURE 1.

Age-standardized incidence and mortality rates (per 100,000) of primary liver cancer, Canada, 1980–2007. Primary liver cancer incidence was defined as C22.02, and mortality, as C22.0, C22.2–C22.73. * p < 0.05 (statistically significant). aapc = average annual percentage change, calculated using the JoinPoint Regression Program (version 3.5.4: U.S. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.).

FIGURE 2.

Age-specific incidence rates (per 100,000) of primary liver cancer in men, Canada, 1980–2007. Primary liver cancer incidence was defined as C22.02. * p < 0.05 (statistically significant). aapc = average annual percentage change, calculated using the JoinPoint Regression Program (version 3.5.4: U.S. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.).

2. RISK FACTORS

The major risk factor for primary liver cancer is infection with viral hepatitis. Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (hbv) accounts for approximately 23% of hcc cases in developed countries, but the percentage is much higher in the developing world, including Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa9. Patients with chronic hbv have a risk of developing liver cancer that is 20–100 times higher than that for uninfected individuals10. Chronic inflammation and repeated cellular regeneration is thought to be the mechanism by which such cases develop, typically after 25–30 years of hbv infection11. Most hbv infections in the developing world are transmitted from mother to child at birth, but worldwide, the virus is also commonly transmitted between sexual partners or through household contact or other activities (for example, needle-sharing) that result in exposure to contaminated blood or body fluids11.

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (hcv), believed to be associated with exposure to contaminated blood, is a more pertinent risk factor for non-hbv-related liver cancers in developed countries12, especially in high-risk populations such as injection drug users and blood transfusion recipients (before hcv screening of blood was implemented in Canada in the early 1990s). Some cases of hcv infection are also attributable to immigration from high-prevalence countries such as Egypt, Italy, and Japan12.

In the United States and some northern European countries, more than half of hcc cases are found to be both hbv- and hcv-negative13, implying that other risk factors may play a role. Those factors include alcohol-related cirrhosis of the liver14,15, fatty liver disease associated with obesity16,17, diabetes18, smoking19, and oral contraceptives20. Less-common risk factors include hereditary hemachromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson disease, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis20.

3. PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The asymptomatic nature of liver cancer means that patients often present with late-stage or advanced malignancy7. Symptoms at presentation can include abdominal pain, abdominal mass, and on occasion, paraneoplastic syndromes, including hypercalcemia, watery diarrhea, hypoglycemia, and erythrocytosis21. Routine ultrasonographic screening of patients with chronic viral hepatitis or cirrhosis may identify asymptomatic early-stage disease that is amenable to treatment and, conceivably, improve survival21. Further details can be found in the recently published Canadian recommendations for the clinical management of hcc22.

4. RISK REDUCTION

In 2008, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc) published updated guidelines for broadening hbv screening to all individuals in the United States who have lived or were born in world regions with intermediate or high hbv prevalence23. Recommendations by the U.S. Institute of Medicine were also recently expanded to include community-based programs for hbv screening, testing, and vaccination services for immigrants24. The cdc also recently released draft guidelines proposing a onetime hcv test for people in the United States born between 1945 and 1965, many of whom are unaware that they are infected with the virus25.

Similar national strategies have not been implemented in Canada, but other options have been recommended, including catch-up hbv immunization for adolescents, screening for hbv in adults and children immigrating from at-risk regions, and prompt screening and treatment of household contacts of liver cancer patients26,27. Those efforts could be complemented with efforts to reduce stigma and to raise awareness in at-risk populations about chronic hbv and hcv infection. Such efforts could include developing a national education and awareness campaign targeting the general public and at-risk communities, creating a national advocacy plan to educate policymakers about the importance of viral hepatitis infections, and ensuring that health care professionals are educated about whom to vaccinate for hbv and to screen for both hbv and hcv28. Primary health care providers can play an additional important role by providing culturally relevant education about the risk factors for liver cancer to their patients as part of the range of disease prevention and control activities outlined in Table i.

TABLE I.

What can primary health care providers do about liver cancer?

|

5. IMPLICATIONS

Liver cancer trends in Canada are partly a result of greater immigration from areas of the world in which liver cancer and hbv are endemic29,30. Census data indicate an ongoing rise in immigration from Asia, with immigrants from other regions of the world making up a smaller percentage of all new arrivals to Canada31,32. There is also some evidence of declining liver cancer incidences in high-risk countries33,34, which might be the result of control of aflatoxin exposure and improvements in coverage with childhood hbv immunization35. How such changes will affect the burden of liver cancer in Canada and other developed countries in relation to chronic hcv infection and fatty liver disease has yet to be seen.

6. SUMMARY

Incidence and mortality rates for primary liver cancer are among the fastest rising for all cancers in Canada, which represents an increasing concern. The role of chronic viral hepatitis infection—together with the potential roles of other risk factors—poses many challenges and calls for a coordinated strategy of disease prevention and control.

7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Steering Committee for Canadian Cancer Statistics for their critical review of this manuscript. In addition to the authors, other members of the Steering Committee on Canadian Cancer Statistics included Maureen MacIntyre (Cancer Care Nova Scotia), Loraine Marrett (Cancer Care Ontario), Les Mery (Public Health Agency of Canada), Hannah Weir (cdc), Larry Ellison (Statistics Canada), Heather Chappell (Canadian Cancer Society), and Lin Xie (Public Health Agency of Canada). The Steering Committee is responsible for the annual production of Canadian Cancer Statistics. The data source for this article was the Canadian Cancer Registry, Statistics Canada.

8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial disclosures to make and no conflicts of interest to report.

9. REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F, et al. globocan 2008 . Ver 1.2. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: iarc CancerBase No 10 [Web resource] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr; cited March 2, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (who) International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (who) International Classification of Diseases. 10th rev. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyer Z, Peltekian K, van Zanten SV. Review article: the changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Canada. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2012. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pocobelli G, Cook LS, Brant R, Lee SS. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence trends in Canada: analysis by birth cohort and period of diagnosis. Liver Int. 2008;28:1272–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas MB, Zhu AX. Hepatocellular carcinoma: the need for progress. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2892–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison LF, Wilkins K. An update on cancer survival. Health Rep. 2010;21:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordenstedt H, White DL, El-Serag HB. The changing pattern of epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42(suppl 3):S206–14. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(10)60507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu CM. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adults with emphasis on the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(suppl):E25–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavanchy D, McMahon B. Worldwide prevalence and prevention of hepatitis C. In: Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, editors. Hepatitis C. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 185–202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Risk factors for the rising rates of primary liver cancer in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3227–30. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makimoto K, Higuchi S. Alcohol consumption as a major risk factor for the rise in liver cancer mortality rates in Japanese men. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:30–4. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ioannou GN, Splan MF, Weiss NS, McDonald GB, Beretta L, Lee SP. Incidence and predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:938–45. 945.e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Fu S, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2005;42:218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldwell SH, Crespo DM, Kang HS, Al-Osaimi AM. Obesity and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(suppl 1):S97–103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:369–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu K, Moriarty C, Caplan LS, Levine RS. Cigarette smoking and primary liver cancer: a population-based case-control study in US men. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:315–21. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blonski W, Kotlyar DS, Forde KA. Non-viral causes of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3603–15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i29.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVita VT, Rosenberg SA, Lawrence TS, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman M, Burak K, Maroun J, et al. Multidisciplinary Canadian consensus recommendations for the management and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:228–40. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i5.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc) Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell AE, Colvin HM, Palmer Beasley R. Institute of Medicine recommendations for the prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Hepatology. 2010;51:729–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.23561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pottie K, Greenaway C, Feightner J, et al. on behalf of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. 2011;183:E824–925. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis B: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(suppl C):5C–24C. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States, Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health (omh) Chronic Hepatitis B in Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders: Goals and Strategies [Web page] Rockville, MD: OMH; 2008. [Available at: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=7241&lvl=2&lvlID=190; cited September 19, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed F, Foster GR. Global hepatitis, migration and its impact on Western healthcare. Gut. 2010;59:1009–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.206763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Yi Q, Mao Y. Cluster of liver cancer and immigration: a geographic analysis of incidence data for Ontario 1998–2002. Int J Health Geogr. 2008;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Statistics Canada. Place of Birth, Generation Status, Citizenship and Immigration Reference Guide, 2006 Census. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2006. Cat. no. 97-557-GWE2006003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Citizenship and Immigration Canada (cic) Facts and Figures 2010: Immigration Overview, Permanent and Temporary Residents. Ottawa, ON: CIC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGlynn KA, London WT. The global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: present and future. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15:223–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Center MM, Jemal A. International trends in liver cancer incidence rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2362–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 4):5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]