Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to determine which factors characterize mothers who expressed their milk by the end of 4 weeks postpartum as well as the duration for which they continued any breastmilk feeding.

Methods

This prospective longitudinal cohort study was conducted with women who donated their milk and clinical data to the Cincinnati Children's Research Human Milk Bank (Cincinnati, OH). We examined the characteristics and length of breastmilk feeding of mothers who expressed their milk within the first month postpartum compared with those mothers who only fed directly at the breast.

Results

By the end of the first 4 weeks postpartum, 63% (37 of 59) of the mothers had begun milk expression. Predictors of milk expression by 1 month were planned work by 6 months, lower infant birth weight, and higher maternal body mass index. Milk expression by 4 weeks did not significantly influence duration of breastmilk feeding.

Conclusions

Breastmilk expression in this cohort was common even within the first month postpartum before mothers in the United States typically go back to work. “Breastfeeding” classification needs to be updated to include options for breastmilk expression so the appropriate study of health outcomes related to this practice can be determined.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is the normative standard to which all other feeding methods should be compared.1 When direct breastfeeding is not possible and an infant is not able to latch to the breast, he or she should be fed the mother's expressed milk.1,2 Out of necessity, infants are routinely fed expressed milk in cases of infant prematurity,3–6 multiple gestation birth,7 and when women return to work.8–10

Even without barriers to directly latching their infant to the breast, however, mothers of full-term, singleton healthy infants also routinely express their milk. In the recent Infant Feeding Practices Study II, the largest study on milk expression in the United States thus far, 85% of the approximately 1,500 breastfeeding mothers of healthy infants expressed their milk at some time between 1.5 and 4.5 months postpartum.11 Approximately 6% of these mothers only expressed their milk without ever putting their infants to the breast.12 In two smaller studies in California, near-exclusive breastfeeding was positively associated with “use of a breast pump” in the first 6 months,13 and low-income mothers given a breast pump did not ask for formula until 4 months after mothers who did not get a pump.14 In two separate cohorts in Australia, mothers who ever expressed their milk were less likely to have discontinued breastfeeding by 6 months compared with those women who never did any expression,15 and 27% of mothers reported that they breastfed longer as a result of breastmilk expression.16 The definition and timing of “breast pump use” and measurement of “breastfeeding” duration were variable for these studies, but all authors recommended further research into the impact of breastmilk expression on duration and outcomes of breastmilk feeding.

The goal of our study was to determine which factors characterized mothers who expressed their milk early in the postpartum period as well as the duration for which they continued any breastmilk feeding. Because breastmilk expression is now an integral part of “breastfeeding”-related activities, characterizing the practice of breastmilk expression is an imperative step in better understanding the related health outcomes.

Subjects and Methods

This prospective longitudinal cohort study was conducted with women who donated their milk and clinical data to the Cincinnati Children's Research Human Milk Bank (Cincinnati, OH).17 The Research Human Milk Bank serves as a repository in which human milk and corresponding data are collected for use for a wide range of research purposes. The Research Human Milk Bank is a voluntary program in which mothers agree to provide milk samples and clinical data weekly for the first month of lactation and then monthly thereafter until they have finished lactating or until 18 months. Participants receive a nominal reimbursement and can discontinue participation at any time. The milk samples are kept within the bank freezers and are available to investigators who have a proposal approved by the Research Human Milk Bank's scientific advisory committee and the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center's Institutional Review Board.

Cohort identification

The cohort for this study included all of the participants enrolled in the Research Human Milk Bank from 2004 until 2007. Participants were solicited in the antepartum and immediate postpartum period through flyers in doctors' offices, maternity hospitals, childbirth classes, and the local print and news media. Mothers were eligible if they were over 18 years old, in good health, and intended to feed their infant at least half breastmilk for 6 months or more. At delivery, all infants were singletons, born at greater than 37 weeks of gestation, weighed more than 2,500 g, and were considered to be medically stable. A trained lactation nurse went to the mother's home within the first week postpartum and reviewed the milk bank protocol and consent form with the mother before final approval.

Clinical data collection

We conducted a literature review of other breastfeeding-related studies to create a standard set of questions that were asked to the mother at the home visits.18 At the first visit mothers were asked their: race (Caucasian or not Caucasian), age (years), highest level of education (not college graduate, college graduate, postgraduate study), marital status (married, single, separated/divorced), parity (first baby or at least second baby), insurance (private insurance or public), type of delivery (cesarean section or vaginal), and gestation of pregnancy (weeks). Mothers were asked their intended length of breastfeeding (months), plans to work at any time in next 6 months (yes or no), and plans to send the infant to child care within the next 6 months (yes or no). At each visit, the nurse asked the mother about feeding-related issues, including the usual method of breastmilk feeding over the past week (at the breast only, expressed and fed breastmilk by bottle only, or a combination of direct breast feedings and expressed milk feedings), type of milk fed (all breastmilk, mostly breastmilk/some formula, half breastmilk/half formula, mostly formula/some breastmilk, all formula), perceived low milk supply (yes or no), maternal-related complications (yes or no to the occurrence of engorgement, sore or cracked nipples, sore breasts or mastitis, plus option for “other”), and infant-related problems (yes or no to the occurrence of poor latch or suck, plus option for “other”) with the first 4 weeks. The terminology “breastmilk feeding” rather than “breastfeeding” was used in all questionnaires and conversations with the mothers as to always be inclusive of expressed milk feedings.

Anthropometric measures

Anthropometric measures used in the analysis were infant birth weight (in grams) and maternal body mass index (BMI) at week 1 postpartum (in kilograms per square meter). Infant birth weight was recorded from maternal report. Maternal weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using an E-Z Carry Portable Digital Scale (Hopkins Medical Products, Baltimore, MD). Standing height was measured with the mother wearing socks, heels together, toes apart at a 45° angle, and head in a horizontal plane. The height was marked on the wall, and the vertical distance to the floor was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Milk sample collection

After completion of the questionnaire and measurements, the nurse helped mothers extract the contents of one breast using the Lactina single-sided, electric breast pump (Medela, McHenry, IL). The mothers were told on the scheduling phone call to try not to feed the infant or express milk from the breast from which they were planning to provide the milk sample. Before the collection, the nurse cleaned the pump with sanitary wipes and assembled all the parts. The nurse helped the mother attach the pump to her breast for the collection. All milk collections were performed by the nurse. The mother did not operate the machinery by herself. Mothers were not given specific instructions on how to express milk beyond the study visit, and the pumping session with the nurse did not count toward the usual method of breastmilk feeding for the infant during that time period. As long as the breast was emptied, any amount of milk collected with each pumping session was considered an appropriate collection. Mothers in the study for the full 18 months provided 21 samples.

Study variables

To classify mothers who expressed their milk by the fourth postpartum week, we examined weekly responses to the survey question, “During the past week of life, how was your breastmilk usually fed?” Mothers who answered “only at the breast” at each of the four home visits were compared with those who answered “pumped then fed by a bottle” or “a combination of at the breast and pumped milk” at any of the four weekly visits within the first month. We derived exclusive breastmilk feeding during the first month postpartum from weekly answers to the question, “Which of the following best describes the type of milk that (infant name) was fed?” Participants were asked to recall within the past week and asked again to recall within the past 24 hours. To be classified as exclusive breastmilk feeding during the first month postpartum, mothers must have answered “all breastmilk” for both the weekly recall and 24-hour recall at each of the first four weekly visits.

Statistical analysis

For the purposes of analyses, breastmilk feeding problems reported in any of the first four home visits were categorized into three groups: perceived low milk supply, maternal problems (including engorgement, sore or cracked nipples, sore breasts, or mastitis), and infant problems (poor latch or suck). We evaluated differences in means using Student's t test and differences in proportions using χ2 or Fisher's exact test for each independent variable (maternal characteristics, anthropometric measures, feeding-related issues, and maternal intentions) with the dependent variable (expressed milk by 4 weeks). Variables associated with early breastmilk pumping with p values of ≤0.2 in bivariate analysis were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model using backward selection and assessed using the Wald χ2 statistic. We used the Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test and area under the curve to evaluate overall model fit.19

We used survival analysis to examine which factors were associated with the duration of any breastmilk feeding and specifically to evaluate whether or not breastmilk expression by 4 weeks postpartum was associated with differences in duration of breastmilk feeding. The mother's last monthly visit time point was used as the time to breastmilk feeding cessation or censoring for mothers who were lost to follow-up. We censored mothers who continued to feed breastmilk beyond the end of the study at 18 months postpartum. We used log-rank tests to evaluate differences in Kaplan–Meier survival curves by milk expression by 4 weeks, maternal and infant birth characteristics, anthropometric measures, feeding-related issues, and maternal intentions. We included variables associated with breastmilk feeding duration in bivariate analysis with p values of ≤0.2 in Cox proportional hazards regression models, and we computed hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We determined changes in estimates of the log likelihood and Wald statistics to assess covariate contribution. Statistical significance was determined at α = 0.05. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct all analyses.

The Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved the methods of cohort identification, consent, data collection, and subsequent data analysis used in this study.

Results

Sixty women enrolled in the milk bank donation program. One mother dropped out before the first home visit, citing that the father of the baby did not want her to breastfeed. The other 59 women in the cohort initiated breastmilk feeding. In the first week, 14% (eight of 59) of the mothers started some milk expression. By the end of the first 4 weeks postpartum, 63% (37 of 59) had begun some milk expression, whereas only 37% (22 of 59) of mothers had only directly fed their infants at the breast since birth. Over three-quarters of the mothers in both groups had not used formula within the first month (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Mothers by Milk Expression Status by 1 Month Postpartum

| |

Milk expression by 4 weeks |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not (n = 22) | Did (n = 37) | p value | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Caucasian | 20 (91%) | 31 (84%) | 0.70 |

| Maternal age (years) | 32.1 ± 4.9 | 31.5 ± 4.3 | 0.62 |

| College graduate | 18 (82%) | 27 (73%) | 0.44 |

| Married | 21 (95%) | 34 (92%) | 1.0a |

| Primiparous | 6 (27%) | 18 (49%) | 0.10 |

| Private insurance | 19 (86%) | 35 (95%) | 0.35 |

| Cesarean section delivery | 6 (27%) | 10 (27%) | 0.98 |

| Gestational weeks at delivery | 40 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 0.81 |

| Anthropometric measures | |||

| Infant birth weight (g) | 3,591 ± 338 | 3,304 ± 431 | 0.01 |

| Maternal BMI at week 1 | 25.42 ± 3.02 | 26.98 ± 3.87 | 0.14 |

| Feeding-related issues | |||

| Exclusive breastmilk feeding during first month postpartum | 19 (86%) | 30 (81%) | 0.73a |

| Perceived low milk supply by 4 weeks | 0 | 4 (11%) | — |

| Maternal problems by 4 weeks | 18 (82%) | 34 (92%) | 0.41a |

| Infant problems by 4 weeks | 4 (18%) | 12 (32%) | 0.29a |

| Maternal intentions | |||

| Breastmilk feeding intent | 0.20a | ||

| 6–9 months | 4 (18%) | 14 (38%) | |

| 12–15 months | 14 (64%) | 20 (54%) | |

| 18–24 months | 4 (18%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Planned work by 6 months | 8 (38%) | 28 (76%) | 0.005 |

| Planned daycare by 6 months | 3 (14%) | 17 (46%) | 0.01 |

Data are reported as number (%) or mean ± SD values.

Statistically significant p values are given in boldface.

By Fisher's exact test.

BMI, body mass index.

The descriptive characteristics of the mothers who fed only at the breast versus those who expressed their milk by 4 weeks are compared in Table 1. Infants of mothers who expressed milk by 4 weeks had significantly lower infant birth weights than those who fed only at the breast. A greater proportion of mothers who expressed milk by 4 weeks planned to work and use child care by 6 months compared with those who fed only from the breast. The frequencies of breastmilk feeding-related problems by 4 weeks postpartum, including perceived low milk supply and maternal or infant-related latch and feeding issues, were not statistically different between these two groups.

Table 2 summarizes the results for the multivariable logistic regression model used to examine predictors of breastmilk expression by 4 weeks postpartum. In the adjusted model, planned work by 6 months, infant birth weight, and maternal BMI at the first visit were associated with expression by the end of the first month. Model diagnostics indicated that the model fit the data well (Hosmer–Lemeshow p value = 0.99) and had good discrimination between those who expressed their milk and those who did not in the first 4 weeks (area under the curve = 0.82 [95% confidence interval 0.71, 0.92]).

Table 2.

Predictors Associated with Breastmilk Expression by 4 Weeks Postpartum Using Logistic Regression

| |

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Unadjusted | Adjusted | p value |

| Planned work by 6 months | 5.06 (1.59, 16.09) | 7.67 (1.86, 31.67) | 0.005 |

| Birth weight (per 100 g decrease) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.38) | 1.34 (1.08, 1.66) | 0.009 |

| Maternal BMI at week 1 | 1.12 (0.95, 1.32) | 1.28 (1.01, 1.60) | 0.04 |

Statistically significant p values are given in boldface.

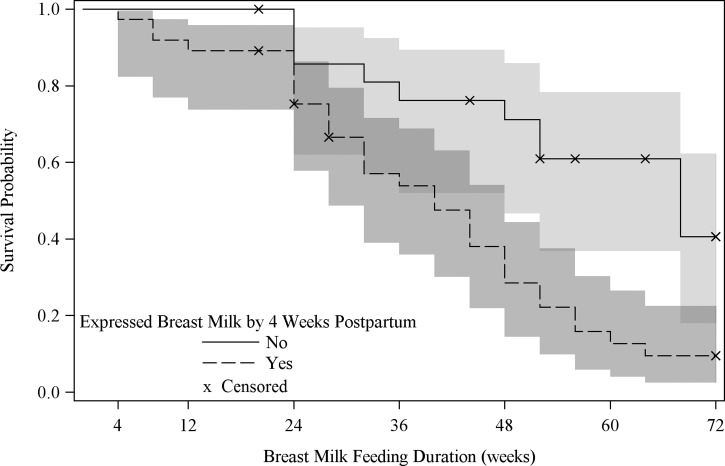

Unadjusted median breastmilk feeding duration was longer in the group of infants who were not fed expressed milk in the first 4 weeks postpartum (median, 68 weeks) compared with those who were (median, 40 weeks) (p < 0.001). The corresponding Kaplan–Meier survival curve is shown in Figure 1. This effect did not persist, however, after adjusting for marital status, parity, maternal BMI at the first home visit, exclusive feeding of breastmilk in the first 4 weeks, and intended length of breastmilk feeding (Table 3). Being married, having more than one child, exclusively breastmilk feeding in the first 4 weeks, and initial intent to feed breastmilk for a longer period of time were associated with decreased hazard ratio (corresponding to an increase in the duration of breastmilk feeding).

FIG. 1.

Unadjusted survival curves with 95% confidence intervals of duration of any breastmilk feeding by mothers who expressed breastmilk by 4 weeks postpartum.

Table 3.

Proportional Hazards Regression Model for Time to End of Breastfeeding

| Predictor | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 0.11 | 0.03–0.44 | 0.002 |

| Single/separated/divorced | Reference | ||

| Parity | |||

| Multiparous | 0.39 | 0.18–0.84 | 0.02 |

| Primaparous | Reference | ||

| Maternal BMI at 1 week (per 1 unit increase) | 1.13 | 1.03–1.25 | 0.01 |

| Exclusive breastmilk feeding in 1st 4 weeks postpartum | |||

| Yes | 0.32 | 0.13–0.82 | 0.02 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Breastmilk feeding intent | |||

| 18–24 months | 0.11 | 0.03–0.48 | 0.003 |

| 12–15 months | 0.16 | 0.07–0.36 | <0.001 |

| 6–9 months | Reference | ||

| Expressed breastmilk during the 1st 4 weeks postpartum | |||

| Yes | 1.78 | 0.83–3.82 | 0.14 |

| No | Reference | ||

Statistically significant p values are given in boldface.

Discussion

The goal of our study was to determine which factors characterized mothers who expressed their milk early in the postpartum period as well as the duration for which they continued any breastmilk feeding. Sixty-three percent (37 of 59) of the mothers in this cohort said that they had expressed their milk by 4 weeks. Although previous studies have shown that maternal employment is strongly predictive of breastmilk expression, our study is unique in that it showed that mothers expressed their milk even prior to returning to work. Mothers who planned to work by 6 months had almost an eight times greater odds of pumping breastmilk by 4 weeks postpartum compared with mothers who did not plan to work by 6 months. Unadjusted rates of breastmilk feeding duration were longer for infants who were not fed expressed milk within the first month after birth. This could indicate that infants' feeding cues were more readily recognized by their mothers and that infants were more effective and efficient at nursing over the long term if they were not fed with bottles.

We also found that the birth weight of the infant and BMI of the mother were associated with milk expression by 4 weeks postpartum. Although mothers did not report that their supply was low, mothers and/or healthcare providers may have been worried that infants with a smaller birth weight were not growing fast enough so mothers may have subsequently expressed their milk so to carefully measure the amount produced and consumed. Heavier women may have had difficulty with delayed lactogenesis, latch and positioning, or poor body image, as has been seen in other studies,20 and more readily resorted to milk expression. Although breastmilk feeding difficulties were not predictive of milk expression in this study, the potential connection with overweight mothers using breastmilk expression is beginning to be recognized.21,22

Women in our cohort who fed their infants breastmilk longer were married, had a baby previously, had a lower BMI at 1 week postpartum, did not use supplemental formula within the first month, and intended to provide breastmilk for a greater period of time (Table 3). Although our study results are not conclusive about the relationship between breastmilk expression by 4 weeks postpartum and duration of breastmilk feeding, it does appear that mothers who express during this early postpartum time may stop breastmilk feeding sooner. We acknowledge that this is a small study with a select group of mothers who may have been more likely to pump their milk because the study nurse helped them with the pump. However, in the two Australian cohorts even more mothers expressed milk—76%15 and 66%,16 respectively—by 4 weeks than in our cohort. Fourteen percent of the mothers in our study expressed their milk prior to the first home visit. All of these studies highlight that healthcare professionals and researchers cannot assume that mothers are feeding their infants directly at the breast even “early” in the postpartum period.

The main advantages to this study were the prospective design curtailing recall bias, systematic data collection, options for mothers to choose a “combination” of at the breast and pumped milk feeding, and direct maternal BMI measurement. Limitations in our sample selection were that it only includes healthy mothers over the age of 18 years who had delivered a healthy, term infant weighing more than 2,500 g whom they said they would try to feed breastmilk for at least 6 months. Mothers who donated to the research milk bank also knew that they were going to be assisted periodically with pumping in order to donate their sample and thus were most likely comfortable with pumping from the outset.

Because this was a secondary analysis, we were limited by the size of the cohort, responses already in the database, and measurements taken for the larger research milk bank purposes. In a subsequent primary study examining the duration of at the breast versus expressed milk feeding, the appropriate sample size could be based on local breastmilk feeding rates and an estimate of the percentage of infants fed pumped milk in the area. Maternity hospitals, lactation consultants, and infant primary care providers may be the best sources for such expressed milk feeding information. We also acknowledge that the question that mothers were asked, “During the past week of life, how was your breast milk usually fed?,” may have resulted in the misclassification of some infants. A mother may have interpreted that an infant fed a bottle of pumped milk only two to three times in a week was not “usually” fed pumped milk; thus she may have chosen the option “At the breast.” Questions in a primary study could be more precisely worded to more accurately assess when an infant is first fed expressed milk and the quantity of feedings either at the breast or expressed. In addition, the research milk bank nurse measured the first postpartum weight to calculate BMI. Pre-pregnancy BMI measurements have been used in large cohort studies evaluating breastfeeding outcomes.23–25 This precludes, therefore, comparison of our results with results in these studies. However, because difficulties related to postpartum BMI may give mothers challenges with latching leading them look for alternatives such as pumping,20 our BMI assessment may, in fact, be more predictive of milk expression when studied in a larger sample. Future studies of breastmilk expression ideally would compare the maternal BMI both prepartum and after delivery, comparing maternal pumping incidence and duration.

We acknowledge that early infant feeding of at the breast versus expressed milk needs to be repeated in a larger, more generalized population. The frequency of breastmilk expression seen in this study and others highlights the necessity to more clearly understand breastmilk expression, however. The seminal studies that established the benefits of “breastfeeding” compared outcomes for mothers and infants directly feeding at the breast with those dyads using breastmilk substitute from a bottle or cup. Feeding expressed breastmilk out of a bottle or cup creates a combination of these once two distinct feeding behaviors. Updated studies are urgently needed to determine the safety and effectiveness of breastmilk production using mechanical means and breastmilk consumption via routes other than at the mother's breast. Just as 20 years ago when the call to more accurately define “breastfeeding” was addressed,26 “breastfeeding” needs to be redefined once again, including options for breastmilk expression starting immediately after birth.27

Conclusions

This study shows that breastmilk expression is common even within the first month postpartum, before mothers in the United States typically go back to work. Breastmilk expression by 4 weeks did not influence the duration of breastmilk feeding in this cohort. The prospective monitoring of breastmilk expression's influence on duration of breastmilk feeding needs to be repeated in a larger, more generalized population with mothers of varying breastmilk feeding intention. “Breastfeeding” classification needs to be updated to include options for breastmilk expression so the appropriate study of health outcomes related to this practice can be determined.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gartner LM. Morton J. Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson PC. Complementary and alternative methods of increasing breast milk supply for lactating mothers of infants in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2010;29:225–230. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.29.4.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier PP. Breastfeeding in the special care nursery. Prematures and infants with medical problems. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:425–442. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(08)70035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier PP. Brown LP. State of the science. Breastfeeding for mothers and low birth weight infants. Nurs Clin North Am. 1996;31:351–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sisk PM. Lovelady CA. Dillard RG, et al. Lactation counseling for mothers of very low birth weight infants: Effect on maternal anxiety and infant intake of human milk. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e67–e75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geraghty SR. Khoury JC. Kalkwarf HJ. Human milk pumping rates of mothers of singletons and mothers of multiples. J Hum Lact. 2005;21:413–420. doi: 10.1177/0890334405280798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biagioli F. Returning to work while breastfeeding. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2201–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fein SB. Mandal B. Roe BE. Success of strategies for combining employment and breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S56–S62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtagh L. Moulton AD. Working mothers, breastfeeding, and the law. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:217–223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labiner-Wolfe J. Fein SB. Shealy KR, et al. Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S63–S68. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shealy KR. Scanlon KS. Labiner-Wolfe J, et al. Characteristics of breastfeeding practices among US mothers. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S50–S55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabritz HA. Hinton BG. Babb J. Maternal hospital experiences associated with breastfeeding at 6 months in a northern California county. J Hum Lact. 2010;26:274–285. doi: 10.1177/0890334410362222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meehan K. Harrison GG. Afifi AA, et al. The association between an electric pump loan program and the timing of requests for formula by working mothers in WIC. J Hum Lact. 2008;24:150–158. doi: 10.1177/0890334408316081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Win NN. Binns CW. Zhao Y, et al. Breastfeeding duration in mothers who express breast milk: A cohort study. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:28. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clemons SN. Amir LH. Breastfeeding women's experience of expressing: A descriptive study. J Hum Lact. 2010;26:258–265. doi: 10.1177/0890334410371209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geraghty SR. Davidson BS. Warner BB, et al. The development of a research human milk bank. J Hum Lact. 2005;21:59–66. doi: 10.1177/0890334404273162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Léon-Cava N. Lutter C. Ross J, et al. Quantifying the Benefits of Breastfeeding: A Summary of the Evidence. Pan American Health Organization; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell FE. Regression Model Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amir LH. Donath S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonard SA. Labiner-Wolfe J. Geraghty SR, et al. Associations between high prepregnancy body mass index, breast-milk expression, and breast-milk production and feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:556–563. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.002352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen KM. Dieterich CM. Zelek ST, et al. Interventions to increase the duration of breastfeeding in obese mothers: The Bassett Improving Breastfeeding Study. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6:69–75. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker JL. Michaelsen KF. Sorensen TI, et al. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:404–411. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilson JA. Rasmussen KM. Kjolhede CL. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with poor lactation outcomes among white, rural women independent of psychosocial and demographic correlates. J Hum Lact. 2004;20:18–29. doi: 10.1177/0890334403261345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nohr EA. Timpson NJ. Andersen CS, et al. Severe obesity in young women and reproductive health: The Danish National Birth Cohort. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labbok M. Krasovec K. Toward consistency in breast-feeding definitions. Stud Family Plann. 1990;21:226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geraghty SR. Rasmussen KM. Redefining “breastfeeding” initiation and duration in the age of breastmilk pumping. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:135–137. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]