Abstract

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) may be the most commonly observed adverse event (AE) associated with the combination of radiation therapy (RT) and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). A significant number of men are trying phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5s) such as sildenafil to treat ED, yet sildenafil studies to date shed little light on the response to ED after ADT.

Aim

The purpose of this trial was to evaluate sildenafil in the treatment of ED in prostate cancer patients previously treated with external beam RT and neoadjuvant and concurrent ADT.

Methods

In this randomized, double-blinded crossover trial, eligible patients received RT/ADT for intermediate risk prostate cancer and currently had ED as defined by the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF). Patients were randomized to 12 weeks of sildenafil or placebo followed by 1 week of no treatment then 12 weeks of the alternative. Treatment differences were evaluated using a marginal model for binary crossover data.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary end point was improved erectile function, as measured by the IIEF.

Results

The study accrued 115 patients and 61 (55%) completed all three IIEF assessments. Sildenafil effect was significant (P = 0.009) with a difference in probabilities of erectile response of 0.17 (95% confidence interval: 0.06, 0.29), and 0.21 (0.06, 0.38) for patients receiving ≤120 days of ADT. However, as few as 21% of patients had a treatment-specific response, only improving during sildenafil but not during the placebo phase.

Conclusions

This is the first controlled trial to suggest a positive sildenafil response for ED treatment in patients previously treated with RT/ADT, however, only a minority of patients responded to treatment. ADT duration may be associated with response and requires further study. The overall low response rate suggests the need for study of additional or preventative strategies for ED after RT/ADT for prostate cancer.

Keywords: Erectile Dysfunction, Sildenafil, Prostate Cancer, Patient Reported Outcomes, Radiation Therapy, Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors Following Prostate Cancer Treatment

Introduction

The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study found that 61.5% of men reported erectile dysfunction (ED) within 2 years following standard four-field radiotherapy (RT) for prostate cancer (PC) [1]. The advent of newer RT technologies, i.e., three-dimensional conformal RT (3D-CRT) and intensity-modulated RT, increased the possibility of sparing a greater amount of normal tissue, and as a result, 3-year post-treatment ED rates ranging from 38% to 41% are now reported [2,3]. However, improvements in normal tissue sparing with 3D-CRT may be offset by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [4]. Multiple clinical trials have shown improved disease outcome when RT is combined with neoadjuvant or adjuvant ADT (RT/ADT) for localized disease [5-7]. However, even short-term ADT increases the rate of ED [8,9], which may be the most commonly observed adverse event (AE) associated with the combination of RT/ADT. ADT alone carries a risk of ED of at least 80% [10]. Conventional wisdom previously held that erectile function after discontinuation of short-term ADT would be equivalent to that after RT alone. However, in our previous work where we reported ED rates of 45% for RT only, 33% for RT/ADT after ADT discontinued and 15% for age-matched controls, rates of ED were 12% higher with RT/ADT even after ADT was discontinued [11].

A significant number of men are trying phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5-Is) such as sildenafil (Viagra®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) to treat ED. Sildenafil is an oral medication that works by enhancing smooth muscle relaxation and inflow of blood into the corpora cavernosa, which occurs in conjunction with sexual stimulation [12]. With minimal side effects, sildenafil has shown efficacy in treating ED after RT in several small, single-institution nonrandomized studies. Among men with various histories and concomitant medical conditions, including men who underwent prior radical prostatectomy or RT, studies suggest that about two-thirds of patients with ED respond to sildenafil [13-18]. However, sildenafil studies to date shed little light on the response to ED after ADT. Unlike RT that primarily causes ED through neurovascular changes over time, ADT affects the central hormonal pathways mediating sexual activity by reducing plasma testosterone levels similar to that of castration. In addition, androgens are key regulators in the expression of many neuronal and endogenous vasodilators (e.g., PDE5-Is) and in connective tissue metabolism; and therefore, ADT can further contribute to ED by impairing the response to endogenous vasodilators [19]. However, the efficacy of the PDE5-Is in treating ED following RT/ADT has not been well studied. As a result, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) sought to address this void by conducting a randomized clinical trial (0215) to evaluate sildenafil in the treatment of ED in PC patients previously treated with RT and neoadjuvant and concurrent ADT. Partner satisfaction with ED treatment outcomes was also assessed and will be reported separately.

Methods

Protocol Development

This symptom management trial was developed as a companion to RTOG 9910, a phase III treatment trial evaluating ADT/RT in intermediate-risk PC. However, in accordance with current Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) funding, which supports infrastructure only, obtaining additional extramural funding was necessary for the distribution of study drug and placebo, which delayed opening of the companion by 3 years after the parent trial opened. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the American College of Radiology and all participating sites.

Patients

Patients receiving treatment at RTOG member or CCOP institutions were candidates for inclusion. Eligibility criteria included clinical T1b-T4 adenocarcinoma of the prostate, no known nodal (N0) or distant metastases (M0), and serum total prostate-specific antigen (PSA) that was ≤100 ng/mL before ADT initiation. All patients were treated with external beam RT without brachytherapy. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was excluded from the parent study. ADT had to include a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue with or without an anti-androgen that was continuously administered for 8–28 weeks prior to RT, maintained until RT completion, and then discontinued post-RT. Initially, a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 18 months must have elapsed since RT completion, but as accrual lagged, the maximum time since RT was expanded to 5 years. In addition, participants were required to have baseline ED as measured by ratings of 0–3 on the International Index of Erec-tile Function (IIEF) Q1 (“How often were you able to get an erection during sexual activity?”).

Study Design

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled two-way crossover clinical trial. Patients were randomized to receive a 12-week supply of either sildenafil or placebo followed by a 1-week washout period before receiving a 12-week supply of the alternative. A flexible dosing schedule was used starting with a 50-mg dose (1 pill) 1-hour prior to desired sexual activity and increasing up to 100 mg (2 pills) daily as needed. Additional pills were made available if necessary. Patient pill diaries were used to record the number of pills used on each date. Patients were requested to take at least two pills per month (6 pills per 12-week period). Patients who took fewer than three pills per period were considered to be non-compliant. AEs were reported according to the Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0.

Study personnel and patients were blinded to treatment assignment for the duration of the study. Patients were stratified before randomization using the Zelen treatment allocation scheme to ensure that within each stratum a balanced number of patients would be allocated to each treatment arm [20]. Stratification factors included: (i) prior use of sildenafil after RT (i.e., no; yes/unsatisfactory response; yes/satisfactory response); (ii) ADT duration (i.e., ≤120 days; >120 days); and (iii) score on the baseline pretreatment IIEF Q1 (i.e., 0–1; 2–3).

Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs)

PRO measures were assessed with the IIEF, the Sexual Adjustment Questionnaire (SAQ), and Locke’s Marital Adjustment Test. Participants were asked to complete PROs at pretreatment, week 12, and 12 weeks after crossover.

The IIEF is a 15-item validated questionnaire developed as a measure of erectile function [21]. Questions specific to erectile function include how often in the past 4 weeks were you able to—“get an erection during sexual activity (Q1),” “penetrate your partner (Q3),” and “maintain your erection (Q4).” Item scores range from 0 to 5: no sexual activity (0); almost never/never (i); a few times (ii); sometimes (iii); most times (iv); and almost always/always (v). The domains of sexual function assessed by this instrument include: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction [22]. Of specific interest was the erectile function domain; scores range from 1 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of erectile function. The series of RT related trials on which we based our hypothesis used Q1 as the primary outcome; however, as time elapsed since the design of the trial, it has become more common to use the sum of Q3/Q4 as the primary outcome in ED trials. We therefore report both for comparison.

The RTOG-modified SAQ is a 20-item questionnaire adapted from the original [23] to reduce patient burden. Psychometric analysis of the modified version demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity and identified five subscales: dysfunction, satisfaction, desire, activity, and fatigue. The RTOG-modified SAQ scores range from to 100, with higher scores indicating an improved quality of sexual life [24].

Statistical Methods

The primary end point of this study was improvement in erectile function as measured by a score of ≥4 on IIEF Q1 post-treatment. Non response/failure was defined as a score of 0–3. The marginal model for binary data [25] was selected to evaluate the efficacy of sildenafil while adjusting for potential period or interaction effects. An effect size of 0.367 was determined as clinically meaningful for this trial assuming that 20% of patients would respond to placebo [26], and (based on lower-bound data from the single institution, nonrandomized RT and sildenafil series [22,27-30]) 75% of patients would respond to sildenafil.

Based on a two-sided comparison at the 0.05 significance level, and adjusting for retrospectively ineligible patients, a sample size of 332 patients would ensure 90% statistical power to detect this difference. The analysis was based on intention to treat and noncompliant patients were included if all IIEF assessments were completed.

Secondary end points included the SAQ and the IIEF erectile function domain. Composite scores were computed using the guidelines associated with each PRO instrument [22,24,31]. Patients must have completed all items in the IIEF erectile function domain and must have completed 15 out of the 20 SAQ items to have a composite score. Missing SAQ item values were determined based on the average values of the completed items. The change scores from placebo to sildenafil treatment were determined for each patient. The paired t-test was utilized to test for a significant treatment difference in the mean change scores at the 0.05 significance level. A clinically meaningful change (CMC) for the SAQ was determined to be 7.0 [24]. A CMC for the IIEF erectile function domain was assumed to be the standard deviation of the baseline scores. The treatment difference in the proportion of patients achieving a CMC was evaluated using McNemar’s test at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Pretreatment Characteristics

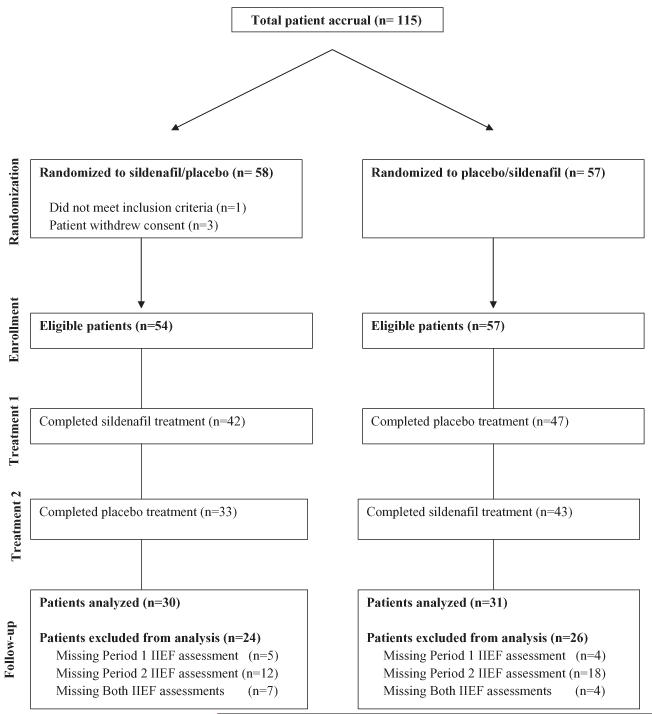

The study accrued 115 patients (35% of planned sample size) from January 3, 2003 to February 17, 2006, and closed because of slow accrual. One patient was ineligible and three patients withdrew their consent (Figure 1). The racial and ethnic distributions of the 111 eligible patients were: 1% Asian; 26% African American; 72% Caucasian; 1% were not reported; and 4% were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Patient characteristics were well-balanced between treatment arms. The mean age was 70 years (range 52, 86). The majority of patients (70%) on each arm had no or poor sexual function upon study entry as indicated by a score of ≤1 on IIEF Q1 and had not previously used sildenafil after RT (82%). Median time from completion of RT was 12 months (range 5.5, 48). The majority of patients (83%) were within 24 months of RT completion. Mean radiation dose was 70.5 Gy (range 70.20, 73.80). Mean testosterone level at study entry was below normal values of 24–95 ng/mL at 14.2 ng/mL (range 0.01, 683). In this study, 96 patients (86%) were castrate at study entry and 11 patients (10%) had subnormal (5–24 ng/mL) testosterone levels. More than three-quarters of the participants had a partner (77%).

Patients were asked about prior sildenafil use (Table 1) and use of mechanical or other agents for ED. Only 4 patients reported prior use of vacuum pump device and no patients reported a penile implant or other agents. Our study was activated January 3, 2003. Vardenafil was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) until August 19, 2003 and tadalafil was not approved by the FDA until November 21, 2003. No patient reported use of these agents.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with missing and complete International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) assessments

| Patients missing IIEF assessments (N = 50) |

Patients completing all IIEF assessments (N = 61) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 71 (7) | 69 (7) | 0.22 | ||

| Range | 52–82 | 55–86 | |||

| Radiation dose (Gy) | |||||

| Mean (standard deviation [SD]) | 70.6 (0.82) | 70.4 (0.63) | 0.64 | ||

| Range | 70.2–72.2 | 70.2–73.8 | |||

| Serum testosterone level (ng/ml) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (56) | 14.7 (88) | 0.97 | ||

| Range | 0.01–294 | 0.23–683 | |||

| Months from completion of radiation therapy/androgen deprivation therapy | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.1 (11.2) | 14.6 (9.4) | 0.45 | ||

| Range | 3.1–48.9 | 3.6–48.3 | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Treatment arm | |||||

| Arm 1 (sildenafil/placebo) | 24 | 48 | 30 | 49 | 0.99 |

| Arm 2 (Placebo/sildenafil) | 26 | 52 | 31 | 51 | |

| Treatment completed per protocol | |||||

| No | 32 | 64 | 5 | 8 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 18 | 36 | 56 | 92 | |

| Zubrod performance status | |||||

| 0 | 48 | 96 | 56 | 92 | 0.45 |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 8 | |

| Prior use of mechanical agents after RT | |||||

| No | 50 | 100 | 57 | 93 | 0.13 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | |

| Prior use of organic nitrates | |||||

| No | 47 | 94 | 61 | 100 | 0.09 |

| Yes | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Penile implant | |||||

| No | 50 | 100 | 61 | 100 | NA |

| Prior use of sildenafil after RT | |||||

| No | 43 | 86 | 49 | 80 | 0.70 |

| Yes—unsatisfactory response | 4 | 8 | 6 | 10 | |

| Yes—satisfactory | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 | |

| IIEF Question 1 Score | |||||

| 0–1 | 35 | 70 | 43 | 70 | 0.99 |

| 2–3 | 15 | 30 | 18 | 30 | |

| Hormonal therapy duration | |||||

| ≤120 days | 25 | 50 | 34 | 56 | 0.57 |

| >120 days | 25 | 50 | 27 | 44 | |

| Partner status | |||||

| No partner | 7 | 14 | 19 | 31 | 0.10 |

| Not married to partner | 6 | 12 | 7 | 12 | |

| Married to partner | 37 | 74 | 35 | 57 | |

| Partner willingness to participate in study | |||||

| No partner | 7 | 14 | 19 | 31 | 0.01 |

| No | 24 | 48 | 14 | 27 | |

| Yes | 19 | 38 | 28 | 46 | |

T-test (continuous) or Fisher’s exact test (discrete).

Mild AEs caused by sildenafil were reported by 4% of all patients including two patients reporting mild changes in vision. Additionally, one patient reported moderate flushing and two patients reported severe headaches. Mild AEs caused by placebo were also reported by 4% of all patients including one patient with abnormal vision. Additionally, three patients on placebo reported moderate headache, flushing, or nasal congestion. No severe AEs caused by placebo were reported.

Compliance

There were no significant differences in pill compliance between the treatment arms. Sixty-seven percent of patients completed both treatment periods per protocol (>150 mg per period). The median number of pills taken during period 1 was 21 (range 3–138). The median number of days pills were taken was 14 (range 2–84). The median number of pills taken during period 2 was 26 (range 3–117). The median number of days pills were taken was 15 (range 3–84).

Completion of PRO Measures and Missing Data

Patients missing the baseline, after placebo, or after sildenafil assessment were excluded from analysis of the primary end point. Standard multiple imputation methods were not applied because of the binary primary end point and crossover trial design. Sixty-one patients (55%) completed all three IIEF assessments and were included in the analysis of the primary end point. Thirty-nine patients (35%) completed one post-treatment assessment and were included in analysis of the secondary end points. Eleven patients (10%) did not complete any post-treatment assessments. Patients included in the primary analysis were more likely to have completed treatment per protocol (P < 0.01). Therefore, the data cannot be assumed to be missing completely at random, and excluding patients with missing data may lead to biased results. However, minimal bias is anticipated as there were no significant differences in the key prognostic factors that could influence treatment response, e.g., prior use of sildenafil, age, partnership status, baseline IIEF score, or duration of hormones between patients excluded from and included in analysis (Table 1).

Response to Sildenafil

IIEF item scores are reported in Table 2. Per the IIEF Q1 score, stratified response rates are detailed in Table 3. Overall, 40 patients (66%) did not respond to either placebo or sildenafil; 6 patients (10%) responded to both placebo and sildenafil; 13 patients (21%) responded to sildenafil, but not placebo; and two patients (3%) responded to placebo, but not sildenafil (Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses with respect to missing data indicate that, if the data were complete, the percentage of patients not responding to either treatment could be as low as 36%. However, with complete data, the percentage of patients responding to sildenafil, but not placebo could only be as large as 31%. A sildenafil effect adjusted for period effects could not be estimated within each stratum because of the small number of informative patients with discordant responses. Overall, there was not a statistically significant period or carry-over effect (P = 0.40 and 0.64, respectively). The response to sildenafil within Arm 1 was equivalent to the sildenafil effect within Arm 2 (P = 0.52), and the overall sildenafil effect was statistically significant (P = 0.009). The estimate of the difference in response between the placebo and sildenafil treatments was 0.17 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.06, 0.29] for all patients and 0.21 [0.06, 0.38] among patients receiving ≤120 days of ADT. There were insufficient numbers of differential responders to accurately examine a difference in patients receiving >120 days of ADT.

Table 2.

International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) item scores at baseline and after each treatment

| Mean scores (SD) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with severe ED (baseline Q1 Score 0–1) (N = 43) |

Patients with moderate ED (baseline Q1 Score 2–3) (N = 18) |

All patients (N = 61) |

|||||||

| IIEF Question | Baseline | Placebo | Sildenafil | Baseline | Placebo | Sildenafil | Baseline | Placebo | Sildenafil |

| Erection frequency (Q1) | 0.23 (0.4) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.7) | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.2) | 0.86 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.8) |

| Erection firmness (Q2) | 0.46 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.1 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.3) | 0.93 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.9) |

| Penetration ability (Q3) | 0.50 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.6(1.7) | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.5) | 0.98 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.8) |

| Maintenance frequency (Q4) | 0.38 (0.7) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.4) | 0.84 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.9) |

| Maintenance ability (Q5) | 0.45 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.7) | 2.2 (2.0) |

| Intercourse frequency (Q6) | 0.83 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.8) |

| Intercourse satisfaction (Q7) | 0.64 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.9) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.6) | 2.3 (2.0) |

| Intercourse enjoyment (Q8) | 0.93 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.3) | 4.0 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.8) | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.5 (2.0) |

| Ejaculation frequency (Q9) | 0.86 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.6 (1.6) | 2.0 (1.8) |

| Orgasm frequency (Q10) | 0.95 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.6) | 3.5 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.9) |

| Desire frequency (Q11) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.4 (0.9) | 4.1 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.3) |

| Desire level (Q12) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.1) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.7 (0.9) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.1) |

| Overall satisfaction (Q13) | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.4) | 3.8 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.5) |

| Relationship satisfaction (Q14) | 2.4 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.6) |

| Erection confidence (Q15) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.1) | 3.2 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.3) |

Scores: 0—no activity; 1—almost never/never; 2—a few times; 3—sometimes; 4—most times; 5—almost always/always.

Those in bold indicate P< 0.001, between sildenafil and placebo treatments (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Table 3.

Response rates to International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Question 1*

| N | Placebo responders only |

Sildenafil responders only |

Placebo and sildenafil responders |

Placebo and sildenafil nonresponders |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 61 | 2 (3%) | 13 (21%) | 6 (10%) | 40 (66%) |

| Prior use of sildenafil | |||||

| No/unsatisfactory response | 55 | 2 (4%) | 12 (22%) | 5 (9%) | 36 (65%) |

| Yes/satisfactory response | 6 | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (67%) |

| Baseline IIEF Question 1 Score | |||||

| 0–1 | 43 | 1 (2%) | 6 (14%) | 2 (5%) | 34 (79%) |

| 2–3 | 18 | 1 (6%) | 7 (39%) | 4 (22%) | 6 (33%) |

| Hormonal therapy duration | |||||

| ≤120 days | 34 | 2 (6%) | 9 (26%) | 4 (12%) | 19 (56%) |

| >120 days | 27 | 0 (0%) | 4 (15%) | 2 (7%) | 21 (78%) |

IIEF Q1: How often were you able to get an erection during sexual activity?

Responders have score of 4—most times or 5—almost always/always.

Figure 2.

Responses to International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Question 1 after each treatment. IIEF Q1: How often were you able to get an erection during sexual activity? Numbers in parentheses represent frequency counts. Responders (+) have score of: 4—most times or 5—almost always/always. n (x, y) represents response status to placebo and sildenafil treatments, respectively.

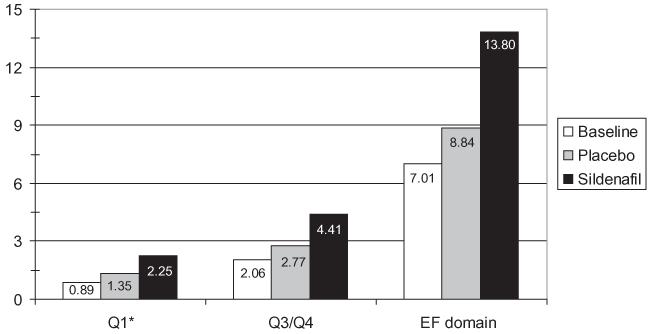

Erectile Function and Sexual Adjustment

Based on the Q3/Q4, nonresponders scored 0–8 and responders scored 9–10. There were 59 patients with baseline to follow-up Q3/Q4 data, of which 47 (79%) did not respond to either treatment, 1 (2%) responded to both treatment and placebo, 10 (17%) responded to sildenafil only, and 1 (2%) responded to placebo only. Sildenafil effects on the IIEF Q3/ Q4 and the IIEF erectile function domain (Q1-Q5, Q15) were evaluated and the mean improvements from placebo to sildenafil were 1.26 and 4.03, respectively (both P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) scores at baseline and after each treatment. Scores: 0—no activity; 1—almost never/never; 2—a few times; 3—sometimes; 4—most times; 5—almost always/always. *IIEF Q1 (primary end point): how often were you able to get an erection during sexual activity? IIEF Q3: When attempting intercourse, how often were you able to penetrate your partner? IIEF Q4: During intercourse, how often were you able to maintain your erection after penetration? IIEF-erectile function (EF) domain score (Q1–Q5, Q15).

For the SAQ total score, the mean improvement was 2.58 (P = 0.02). Although statistically significant, these magnitudes are not clinically significant. Based on the proportion of patients achieving a CMC, there was no sildenafil effect on the SAQ (18% placebo only vs. 23% sildenafil only, P = 0.53). There was, however, a significant sildenafil effect on the IIEF erectile function domain score (8% placebo only vs. 25% sildenafil only, P = 0.03).

Discussion

Patients who are treated for localized PC generally have a low risk of cancer-specific mortality, but may have their life complicated by long-term treatment-related side-effects. The importance of sexual functioning as a quality-of-life (QOL) issue is significant. In a controlled study of 522 men, satisfaction with sexual life was found to be a powerful predictor of satisfaction with life as a whole [32]. Similarly, among cancer survivors, a QOL study concluded that cancer survivors enjoy QOL similar to their noncancer counterparts in all but one aspect of daily life: sexual functioning [33].

There have been five observational reports of the efficacy of sildenafil in the treatment of ED in patients who have either received RT alone [14] or RT/ADT [17,18,34,35]. All of these studies were nonrandomized, single-institution studies with convenience samples of small sizes ranging from 21 to 50 patients, with one study accruing 152 subjects [34]. Mean age among three of the studies [17,18,35] were similar to the current sample of men who completed the IIEF at age 69, with one study reporting on men with a mean age of 65.7 years [14] and another on men with a mean age of 62 years [34]. As in the current study, three [14,18,35] of the four studies employed 3D-CRT, one reported on patients treated with 3D-CRT or brachytherapy [34] and one study used a four-field technique [17]. Most prescribed sildenafil 50 mg titrated to 100 mg as needed, but not all studies reported on compliance, doses taken or frequency of use. The sildenafil response rates for improvement in erectile function ranged widely from 26% to 91%. However, all studies used different metrics for reporting response. One study used a measure of ED that was not validated [18] and one used a validated measure other than the IIEF [14,35]. Three studies used the IIEF [14,17,34] but reported on different domains or items and one, which excluded patients treated with ADT, reported response by individual IIEF items and overall response was reported with the single global item that assessed frequency of ability to achieve firm erections, which was not part of the scoring of the IIEF [14].

The study by Weber and colleagues, reported an improved total IIEF score in 50% of patients who had received concomitant hormones [17]. Compared with the current study where patients had been off hormones a mean of 14.6 months, the patients in this study had been off hormones a mean of 20.5 months. While testosterone levels were not reported in the study by Weber and no conclusions can be drawn, it is plausible to hypothesize that the better response to sildenafil in men previously treated with concomitant hormones may have been associated with better testosterone recovery over the additional 6 months before starting sildenafil post-RT compared with the current study. Of note is that the Weber study treated patients using the less precise four-field technique, which theoretically should have had higher rates of ED compared with the more normal tissue-sparing conformal technique employed in the current study, regardless of testosterone status.

The study by Teloken et al. [34] specifically assessed response to sildenafil in patients previously treated with ADT. ADT resulted in lower response rates to sildenafil at 24-month follow-up as compared with patients treated with RT alone (47% vs. 61%, P = 0.032), however how long patients had been on ADT, how long ADT had been discontinued, and testosterone recovery were not reported [34].

To date, there has only been one other controlled trial of the efficacy of sildenafil for ED in PC patients, but this trial excluded patients who had previously been treated with ADT [36]. In this randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled trial, PC patients were treated with 3D-CRT alone. In terms of ED, sildenafil was found to be effective in 45% of the patients vs. 8% after placebo, and successful intercourse was reported in 55% of the patients after sildenafil vs. 18% after placebo. We observed a lower response rate (31%) to sildenafil than reported by this study [36], but their work excluded patients treated with ADT. We also observed a lower response rate than reported in the smaller nonrandomized studies of patients treated with RT/ADT [17,18,35] or RT alone [14].

Differences in findings among the current and previous studies may be related to study design or patient characteristics. In terms of design, this study was prospective, placebo-controlled, and used validated self-report questionnaires to ascertain sildenafil efficacy. Further, although this study did not meet its accrual goal, it included almost twice the number of analyzable participants (N = 61) than the sum of patients treated with RT/ADT in other nonrandomized reports (N = 35) [17,18,35]. In terms of patient characteristics, it is possible that sildenafil may have been less effective than in previous trials because most of our participants had substantially impaired erectile function at baseline. For example, the mean IIEF Q1 (erectile frequency) score was 0.89 in the current study as compared with 1.7 in the randomized study by Incrocci et al. [36] and 2.19 in the study by Kedia et al. [14], neither of which included ADT. The men in this study were also slightly older than many of the other studies reported here, and were hypogonadal at study entry.

Patients may also have had ED prior to ADT/RT, so there may have been multiple causes for their ED; it is possible this may have contributed to a lesser than previously observed sildenafil response rate. Furthermore, our study did not require the use of highly conformal image-guided RT methods to minimize dose to erectile tissues and their vascular supply. These factors may have contributed individually or in some collective fashion to the results. Nonetheless, these observations suggest that future research should focus on alternatives to reverse ED in this patient population through earlier intervention or through preventative strategies.

In this study, patients who received a shorter duration of ADT (≤120 days) appeared to receive a greater benefit in erectile response to sildenafil than was noted in the overall study group. This raises a question for future research whether there is a synergistic effect of RT/ADT that continues after the ADT discontinuation on erectile function and response to PDE5-Is.

The major limitations of this study were the lower than expected accrual and the amount of missing data, a common challenge with PROs, which prevented a more conclusive examination of the possible effect of ADT duration on response to sildenafil therapy. To this point RTOG is prospectively testing a new method of electronic PRO data capture to assess if this technology is able to decrease data attrition.

In addition, while many factors may have contributed to slow accrual, the additional burden of obtaining extramural funding for symptom management trials is a major barrier to the conduct of such trials in the cooperative group setting. While the NCI-funded analysis of the cooperative group protocol development process has recently been published, few solutions have been proposed that may help inform new initiatives trying to streamline the process specifically for symptom management trials [37].

Another study limitation was the incomplete recovery of testosterone levels, which may have reduced both the total number of days the drug was used (because of decreased libido) and the response rate. Testosterone recovery to normal levels was not an eligibility criterion to this study, nor was testosterone level followed longitudinally in these patients. Further, emerging data on other biomarkers may be pertinent in future work that may better predict responders vs. nonresponders to ED interventions. For example, one recent report of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) suggests that men with the XRCC1 rs25489 G/A (Arg280His) genotype were more likely to develop ED after RT than men who had the G/G genotype (67% compared with 24%; P = 0.048) [38].

A limitation to this and most similar trials is the absence of data on co-morbidities. There are several well documented factors that may contribute to ED including diabetes, smoking, and psychological issues, as well as certain medications, all highly prevalent in aging men, that may affect response to ED medications. They were not included in this trial for pragmatic reasons of patients being on two trials simultaneously and the concern for patient burden. However, future trials would be strengthened by assessing these factors. Finally, while a flexible daily dosing of sildenafil was encouraged, only a minimum of two pills per month was required per protocol with a minimum of three pills per 12-week period considered for analysis. The median number of pills taken during each 12 week period 1 and 2 was 21 and 14, respectively. Since the protocol was written in 2002 a number of sexual rehabilitation articles following radical prostatectomy have been published suggesting more frequent dosing of at least three times per week [39] or daily [40] may be more efficacious, although some studies indicated no difference compared with on-demand dosing [41,42]. A more intensive dosing and possibly a longer regimen may be necessary for optimal results and should be considered in future trials. As with penile rehabilitation with radical prostatectomy, starting ED treatment earlier in this patient population may also have benefit, however the challenge of compliance with earlier treatment in patients with low libido while on ADT would need careful consideration.

Conclusions

It is important to understand ED in the context of ADT used in combination with RT because of the frequent use of ADT with RT in men with localized PC. This is the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate that at least some patients with ED who received prior RT and short-term ADT will respond to sildenafil. Nonetheless, the findings raise the concern that only about one in four patients respond better to sildenafil than to placebo and that overall sexual adjustment for the group demonstrated no clinically significant improvement. These findings, if substantiated in larger trials, may have a significant impact on patient decision making if the incremental improvements in intermediate stage PC treated with ADT are weighed against the incidence of ED and low response to PDE5-Is. However, the results noted in this study are suggestive and should be considered as an exploratory basis for a larger clinical trial that includes an assessment of the interaction among PDE5-Is, ADT duration, hypogonadal status, and possible genetic predictors of response.

Acknowledgment

This research was made possible by financial support from the National Institute of Nursing Research R01 NR07971-01, the National Cancer Institute through the Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP), the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Grant CA21661, CA32115, and CA37422 awarded by the National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Prevention. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Pfizer, Inc. supported this trial with drug and placebo, no other payments were received.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Statement of Authorship

Category 1

(a) Conception and Design

Deborah Watkins Bruner; Thomas Pisansky; Lisa Kachnic; Lawrence Berk

(b) Acquisition of Data

Marvin Rotman; Thomas Corbett; Joycelyn Speight; Roger Byhardt; Howard Sandler

(c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Jennifer James; Soren Bentzen

Category 2

(a) Drafting the Article

Deborah Watkins Bruner; Jennifer James; Charlene Bryan; Thomas Pisansky; Soren Bentzen

(b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

Deborah Watkins Bruner; Thomas Pisansky

Category 3

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Article

Deborah Watkins Bruner; Lisa Kachnic; Lawrence Berk; Howard Sandler

References

- 1.Potosky A, Legler J, Albertsen PC, Stanford JL, Gilliland FD, Hamilton AS, Eley JW, Stephenson RA, Harlan LC. Health outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1582–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little DJ, Kuban DA, Levy LB, Zagars GK, Pollack A. Quality-of-life questionnaire results 2 and 3 years after radiotherapy for prostate cancer in a randomized dose-escalation study. Urology. 2003;62:707–13. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Wielen GJ, van Putten WL, Incrocci L. Sexual function after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Results from a dose-escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Ward E, Ries LA, Schrag D, Jamison PM, Jemal A, Wu XC, Friedman C, Harlan L, Warren J, Anderson RN, Pickle LW. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1407–27. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:289–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanks GE, Pajak TF, Porter A, Grignon D, Brereton H, Venkatesan V, Horwitz EM, Lawton C, Rosenthal SA, Sandler HM, Shipley WU. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Phase III trial of long-term adjuvant androgen deprivation after neoadjuvant hormonal cytoreduction and radiotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the prostate: The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Protocol 92–02. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3972–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roach M, 3rd, Bae K, Speight J, Wolkov HB, Rubin P, Lee RJ, Lawton C, Valicenti R, Grignon D, Pilepich MV. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy and external-beam radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: Long-term results of RTOG 8610. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:585–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollenbeck BK, Wei JT, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Sandler HM. Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy impairs sexual outcome among younger men who undergo external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2004;63:946–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelefsky MJ, Chan H, Hunt M, Yamada Y, Shippy AM, Amols H. Long-term outcome of high dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2006;176(Pt 1):1415–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potosky AL, Reeve BB, Clegg LX, Hoffman RM, Stephenson RA, Albertsen PC, Gilliland FD, Stanford JL. Quality of life following localized prostate cancer treated initially with androgen deprivation therapy or no therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:430–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.6.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruner DW. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness outcomes of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Sonoma, CA: Report, First Sonoma Conference on Prostate Cancer. ONC News International. 1997;6(supplement 3)(11) [Google Scholar]

- 12.McVary KT. Clinical practice. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2472–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp067261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boolell M, Allen MJ, Ballard SA, Gepi-Attee S, Muirhead GJ, Naylor AM, Osterloh IH, Gingell C. Sildenafil: An orally active type 5 cyclic GMP specific phosphodisterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kedia S, Zippe CD, Agarwal A, Nelson DR, Lakin MM. Treatment of erectile dysfunction with sildenafil citrate (Viagra) after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54:308–12. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merrick GS, Butler WM, Lief JH, Stipetich RL, Abel LJ, Dorsey AT. Efficacy of sildenafil citrate in prostate brachytherapy patients with erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1999;53:1112–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreland R, Goldstein I, Traish I. Sildenafil, a novel inhibitor of phosphodiesterase type 5 in human corpus cavernosum smooth muscle cells. Life Science. 1998;62:PL309–18. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber DC, Bieri S, Kurtz JM, Miralbell R. Prospective pilot study of sildenafil for treatment of postradiotherapy erectile dysfunction in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3444–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelefsky MJ, McKee AB, Lee H, Leibel SA. Efficacy of oral sildenafil in patients with erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for carcinoma of the prostate. Urology. 1999;53:775–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00594-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greco EA, Spera G, Aversa A. Combining testosterone and PDE5 inhibitors in erectile dysfunction: Basic rationale and clinical evidences. Eur Urol. 2006;50:940–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:365–75. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IEFF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson AM, Speakman MJ, Dinsmore WW, Giuliano F, Gingell C, Maytom M, Smith MD, Osterloh I, Sildenafil Multicentre Study Group. Sildenafil multicentre study group Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) is effective and well tolerted for treating erectile dysfunction of psychogenic or mixed aetiology. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54:561–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waterhouse J, Metcalfe M. Development of the sexual adjustment questionnaire. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1986;23:451–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruner DW, Scott C, McGowan D, Lawton C, Hanks G, Prestidge B, Han S, Gore E, Asbell S, Rotman M. Factors influencing sexual outcomes in prostate cancer patients enrolled on radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) studies 90-20 and 94-08 [Abstract]; Paper presented at: 5th Annual Conference of the The International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISQOL); Baltimore, MD. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker MP, Balagtas CC. Marginal modeling of binary crossover data. Biometrics. 1993;49:997–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meuleman E, Cuzin B, Opsomer RJ, Hartmann U, Bailey MJ, Maytom MC, Smith MD, Osterloh IH. A dose-escalation study to assess the efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in men with erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2001;87:75–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawton K, Catalan J, Fagg J. Sex therapy for erectile dysfunction: Characteristics of couples, treatment outcome, and prognostic factors. Arch Sex Behav. 1992;21:161–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01542591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hultling C. Partners’ perceptions of the efficacy of sildenafil citrate (VIAGRA) in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;102(suppl):16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintz D. Unusual case report: Nonpharmacologic effects of sildenafil. Psychiatric Service. 2000;51:674–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roach M, III, Chinn DM, Holland J, Clarke MA. A pilot survey of sexual function and quality of life following 3D conformal radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:869–74. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimmel D, Van Der Veer F. Factors of marital adjustment in Locke’s Marital Adjustment Test. J Marriage Fam. 1974:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fugl-Meyer AR, Lodnert G, Branholm IB, Fugl-Meyer KS. On life satisfaction in male erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1997;9:141–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olweny CLM, Juttner CA, Rofe P, Barrow G, Esterman A, Waltham R, Abdi E, Chesterman H, Seshadri R, Sage E, Andary C, Katsikitis M, Roberts M, Selva-Nayagam S. Long-term effects of cancer treatment and consequences of cure: Cancer survivors enjoy quality of life similar to their neighbors. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:826–30. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teloken PE, Ohebshalom M, Mohideen N, Mulhall JP. Analysis of the impact of androgen deprivation therapy on sildenafil citrate response following radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;178:2521–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valicenti RK, Choi E, Chen C, Lu JD, Hirsch IH, Mulholland GS, Gomella LG. Sildenafil citrate effectively reverses sexual dysfunction induced by three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy. Urology. 2001;57:769–73. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Incrocci L, Koper PC, Hop WC, Slob AK. Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and erectile dysfunction following external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:1190–5. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01767-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dilts DM, Sandler AB. Invisible barriers to clinical trials: The impact of structural, infrastructural, and procedural barriers to opening oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4545–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burri RJ, Stock RG, Cesaretti JA, Atencio DP, Peters S, Peters CA, Fan G, Stone NN, Ostrer H, Rosenstein BS. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in SOD2, XRCC1 and XRCC3 with susceptibility for the development of adverse effects resulting from radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiat Res. 2008;170:49–59. doi: 10.1667/RR1219.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee DJ, Cheetham P, Badani KK. Penile rehabilitation protocol after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Assessment of compliance with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy and effect on early potency. BJU Int. 2010;105:382–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathers MJ, Klotz T, Brandt AS, Roth S, Sommer F. Long-term treatment of erectile dysfunction with a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor and dose optimization based on nocturnal penile tumescence. BJU Int. 2008;101:1129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirone V, Imbimbo C, Rossi A, Sicuteri R, Valle D, Longo N, Fusco F, Italian Sure Study Group Evaluation of an alternative dosing regimen with tadalafil, three times per week, for men with erectile dysfunction: SURE study in Italy. Asian J Androl. 2007;9:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shindel AW. 2009 update on phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy part 1: Recent studies on routine dosing for penile rehabilitation, lower urinary tract symptoms, and other indications (CME) J Sex Med. 2009;6:1794–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01347.x. quiz 1793, 1809–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]