Abstract

The insolubility of the disease-causing isoform of the prion protein (PrPSc) has prevented studies of its three-dimensional structure at atomic resolution. Electron crystallography of two-dimensional crystals of N-terminally truncated PrPSc (PrP 27–30) and a miniprion (PrPSc106) provided the first insights at intermediate resolution on the molecular architecture of the prion. Here, we report on the structure of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 negatively stained with heavy metals. The interactions of the heavy metals with the crystal lattice were governed by tertiary and quaternary structural elements of the protein as well as the charge and size of the heavy metal salts. Staining with molybdate anions revealed three prominent densities near the center of the trimer that forms the unit cell, coinciding with the location of the β-helix that was proposed for the structure of PrPSc. Differential staining also confirmed the location of the internal deletion of PrPSc106 at or near these densities.

Keywords: electron microscopy, immuno-labeling, two-dimensional crystals, miniprion, uranyl binding, ammonium molybdate

INTRODUCTION

Prion diseases, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie, are caused by an alternatively folded prion protein (PrP) isoform designated PrPSc [1]. PrPSc seems to be the sole component of the infectious prion particle, as demonstrated by the ability of recombinant (rec) PrP, derived from E. coli and refolded into a β-rich isoform, to induce prion disease in mice [2]. PrPSc is formed from cellular PrP (PrPC) by a profound, conformational change [3]. PrPSc is characterized by its insolubility, while PrPC is amenable to solubilization with non-denaturing detergents [4]. The unremitting insolubility of PrPSc has hampered all attempts to study its structure by conventional techniques such as X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy [5, 6].

In contrast to PrPSc, the structure of unglycosylated recPrP produced in E. coli, a useful surrogate for PrPC, has been solved by NMR spectroscopy. recPrP contains a bundle of three α-helices and little β-structure [7–16]. The results of an NMR spectroscopical study on PrPC isolated from bovine brain are consistent with the data obtained from recPrP [17]. X-ray crystallography of recPrP shows structures similar to those determined by NMR spectroscopy [18–20]; furthermore, crystals of recPrP with the human sequence may have revealed a domain-swapped dimer [18].

The first insights into the structure of PrPSc emerged from studies of sucrose gradient fractions highly enriched for prion infectivity. Those fractions contained PrP 27–30, which polymerized into rod-shaped particles with the ultrastructural and tinctorial properties of amyloid [21]. All amyloids are filamentous polymers of proteins with a high β-sheet content [22]. PrP 27–30 is the protease-resistant fragment of PrPSc consisting of the C-terminal ~140 amino acids. Optical spectroscopy confirmed the high β-sheet structure of both PrPSc and PrP 27–30 [3, 23–26] and X-ray fiber diffraction of prion rods gave very weak but characteristic reflections at 4.7 Å indicative of cross-βstructure [27]. Antibody mapping studies argued that when PrPC is converted into PrPSc, a conformational rearrangement occurs in a central domain consisting of residues 90–176 [19, 28, 29].

Previously, we reported two-dimensional (2D) crystals of PrP 27–30 that appeared to be alternative multimerization products of prion rods. Digital image processing enabled us to improve the quality of the images considerably, allowing the visualization of molecular details [30]. In addition, we observed isomorphous 2D crystals in preparations of a miniprion, PrPSc106, formed from PrP106 that lacks residues 23–88 and 141–176 [31]. Transgenic mice expressing PrP106 on a Prnp0/0 background produce miniprions [32]. By mapping the differences between the two crystal forms, we were able to localize the internal deletion of PrPSc106. In addition, we obtained a difference signal for the N-linked oligosaccharides of PrP 27–30, reflecting the differences in glycosylation between PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 [30, 32, 33]. The location of the N-linked sugars was independently confirmed by specific labeling with Monoamino Nanogold. These results were used to constrain structural models of PrPSc and only models containing a parallel β-helix satisfied all experimental constraints [30].

Here, we report the binding and interaction of different heavy metal salts, used as negative stains to PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106. By expanding earlier studies on the binding of uranyl salts to PrP 27–30 [30], we discovered that the counter-ion of the uranyl salt participates in complex formation and that the size of the anion can sterically constrain the interaction. Furthermore, we observed that PrPSc106 — in contrast to PrP 27–30 — does not bind uranyl oxalate, showing that partial or full negative charges contribute substantially to the interaction since almost all negatively charged residues are deleted from PrPSc106. This finding, in turn, allowed us to localize the internal deletion of PrPSc106 at the center of the trimeric oligomer, independently confirming our earlier interpretation [30]. The negative stain ammonium molybdate revealed a three-fold symmetry of the unit cell; these stain-excluding densities overlap with the locations of the proposed parallel β-helices in our model of PrP 27–30. This model readily explains the staining behavior of both PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 with a variety of heavy metal, negative stains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106

Murine (Mo) PrP 27–30 was prepared from the brains of scrapie sick, RML-infected, wild-type FVB mice; SHa PrP 27–30 was prepared from the brains of ill, Sc237-infected Syrian hamsters. PrPSc106 was prepared from the brains of RML-infected mice harboring the chimeric mouse-hamster (MHM2) PrP106 transgene [31, 32]. The purification was performed as published [34]. The final step of this procedure consisted of a sucrose gradient centrifugation. As previously described [30], we discovered that some fractions of the sucrose gradient contain, in addition to the normally observed prion rods, 2D crystals. The crystals co-purified with the prion rods and migrated to the same density step in the sucrose gradients. Silver-stained SDS gels of these samples routinely showed only the three bands of PrP 27–30 (representing the di-, mono-, and unglycosylated isoforms of PrP 27–30); no other proteins were detected. These 2D crystals are different from those that were grown from PrP 27–30 solubilized in reverse micelles [5]. The current 2D crystals originate in preparations that have high titers of infectivity and have not been treated by denaturing agents; therefore we consider these crystals to be fully infectious.

Negative-stain electron microscopy

Negative staining was performed on carbon-coated, 600-mesh copper grids that were glow-discharged prior to staining. Five-µl samples were adsorbed for up to 5 min, briefly washed with 0.1 M and 0.01 M ammonium acetate buffer, pH 7.4, and stained with two droplets (50 µl each) of freshly filtered staining solutions. We used the following staining solutions: 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate (unbuffered, pH ~3.6, or in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0); 2% (w/v) ammonium molybdate (unbuffered, pH ~5.5); 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate in 200 mM sodium oxalate buffer, pH 4.0 (to form uranyl oxalate); and 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate in 200 mM sodium phthalate buffer, pH 4.0 (to form uranyl phthalate). After drying, the stained samples were viewed in either a Jeol JEM 100 CX II electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV or an FEI Tecnai F20 electron microscope at acceleration voltages of either 80 kV or 200 kV. Images were recorded on Kodak 4489 photographic film or a digital camera (either a 1024 × 1024 Gatan 694 Slow-Scan CCD camera or a 4096 × 4096 Gatan UltraScan 4000 CCD camera) at magnifications between 40,000 and 120,000. For the digital electron micrographs, the effective pixel size ranged from ~1.2 Å/pixel to ~3.5 Å/pixel, depending on the magnification.

Immunolabeling

The immunolabeling was performed essentially as described [35]. Briefly, 5-µl aliquots of samples rich in 2D crystals were adsorbed for 5 min onto glow-discharged formvar/carbon-coated nickel grids. The grids were washed 3 times with ammonium acetate buffer (0.1 M and 0.01 M), prestained with 3 drops of 2% uranyl acetate, and rinsed with Tris buffered saline (TBS: 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl). Afterwards, the grids were blocked for 10 min with 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS, incubated with the primary antibody (R1, R2, 28D [28, 36], and 3F4 [37]) for 1 h, rinsed 5 times with 0.1% BSA in TBS, incubated with a bridging rabbit anti-mouse antibody for 30 min, again rinsed 5 times with 0.1% BSA in TBS, incubated with a 10-nm-gold–conjugated, goat anti-rabbit antibody (Ted Pella, Inc.) for 30 min, rinsed 5 times with 0.1% BSA in TBS, 2 times with TBS alone, and 2 times with water. Controls were treated identically, except that the primary antibody was omitted. Finally, the grids were counter-stained with 3 drops of 2% uranyl acetate and air-dried.

Image processing

Images of reasonably well ordered 2D crystals were taken at a calibrated magnification of 121,200, which is equivalent to either ~1.2 Å/pixel or ~2.2 Å/pixel depending on which digital camera was used. For image processing, only images of 2D crystals taken with the Tecnai F20 electron microscope operating at 200 kV were used. The image processing was completed essentially as described previously [30]. Briefly, the contrast transfer function (CTF) was corrected using the CRISP software package [38]. In case of the uranyl acetate-stained 2D crystals, CRISP was also used to compensate partially for the dampening of the CTF function at higher resolution. The CTF-corrected images were processed using a single-particle, real-space approach by correlation-mapping a manually chosen 256 × 256 pixel reference onto the original image [39, 40]. The reference image contained typically ~40 unit cells. The resulting average was used in a rotational and translational search to align the individual subsets of the original image. Correlation-mapping and -averaging were completed using routines written for the SPIDER and WEB software package [41]. After up to ~25 iterations, the algorithm converged and no further improvements could be achieved.

Previously, the power spectra of the final correlation averages showed spots out to ~7 Å, which we recognized as unlikely to reflect the true resolution limit of the 2D crystals [30]. At the time, we attributed the appearance of these artificial, high-resolution data to the binding of uranyl ions to the crystal lattice. After processing the current, higher-resolution electron micrographs, the power spectra again revealed unexpectedly high-resolution spots (data not shown). By adjusting our image processing routine, we were now able to suppress these artificially high-resolution data and obtained a more realistic resolution limit of 10–15 Å.

The aligned subsets from the 2D crystal were examined by correspondence analysis [41] to ensure that only a homogeneous population of images was averaged. The final correlation average was used for crystallographic analysis and averaging, again using the CRISP software package [38]. As seen before [30], both the raw 2D crystals as well as the correlation averages showed a clear p3 plane group symmetry (Table 1), hence a p3 symmetry was applied during crystallographic averaging.

Table 1.

Plane group statistics for a typical PrP 27–30 2D crystal.

| Plane group residual (°) |

Amplitude Rsym factor (%) | Amplitude-weighted phase |

|---|---|---|

| p1 | — | — |

| p21 | — | 34.2 |

| p3 | 13.2 | 14.3 |

| p312 | 20.8 | 30.5 |

| p321 | 20.8 | 28.2 |

| p6 | 13.2 | 37 |

| p622 | 24.1 | 49.5 |

To calculate an average from several, independent 2D crystals, we took one of the images as a reference and aligned the other images pairwise with the reference in order to find the best alignment parameters. In addition to the routine rotational and translational alignment procedure, we rotated one of the images by 180°, mirrored the image along the y-axis, or both. This step allowed us to escape local minima in our search for an optimal alignment. The parameters that gave the lowest variance value in the pairwise alignments were used to calculate the final average. For the difference-mapping procedure, we used the same approach to determine the best alignment parameters.

RESULTS

Uranyl complexation and staining properties of the 2D crystals

Previously, we reported that 2D crystals of PrP 27–30 stained with certain uranyl salts (uranyl acetate and uranyl oxalate, but not uranyl citrate) show a mixture of positive and negative staining. We observed that the binding of uranyl ions onto the 2D crystal lattice of PrP 27–30 competes with the intrinsic stability of the uranyl–counter-ion complex. The 2D crystals of PrP 27–30 showed the same staining behavior, i.e. complexation pattern, with uranyl acetate and uranyl oxalate [30]. Uranyl acetate and uranyl oxalate have stability constants (pK) of 3.2 and 6.5, respectively [42, 43]. That PrP 27–30 forms complexes with uranyl oxalate indicates a strong binding between the uranyl ions and the protein. However, uranyl citrate with a pK value of 18.9 [42, 43] showed a different staining behavior. The uranyl ions formed tight complexes with the citrate and prevented it from binding PrP 27–30, thus acting as a negative stain, which contrasts with the positive staining observed with uranyl acetate and uranyl oxalate [30].

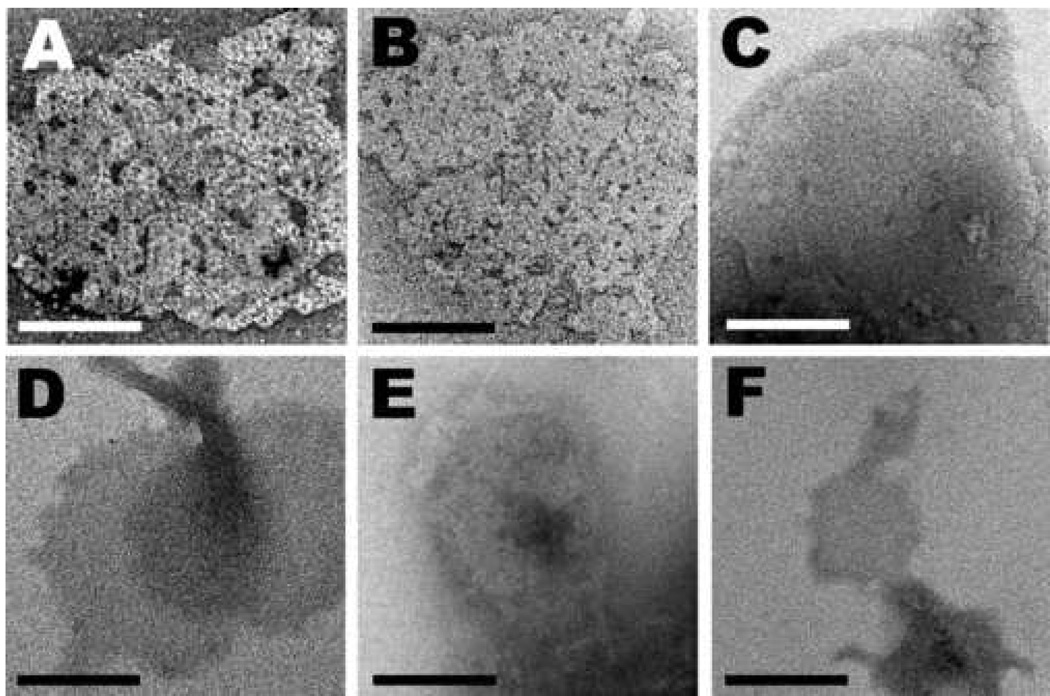

To explore further the interaction of uranyl ions with PrP, we stained PrPSc106 with uranyl oxalate. In contrast to PrP 27–30 (Figures 1A and 1B), PrPSc106 cannot compete with the oxalate counter-ion to bind uranyl ions in the center of the subunit (Figure 1C). This finding demonstrates that the negatively charged residues that are deleted in PrP106 contribute to the strength of the uranyl•PrP complex. Most important, this finding confirms independently the localization of the internal deletion of PrPSc106 to the center of the unit cell.

Fig. 1.

Staining of 2D crystals with 2% uranyl oxalate (top row) or with 2% uranyl phthalate (bottom row). (A, D) Crystals of PrP 27–30 prepared from Syrian hamster-adapted Sc237 prions. (B, E) Crystals of PrP 27–30 prepared from mouse-adapted RML prions. (C, F) Crystals of PrPSc106 prepared from MHM2 mouse-adapted RML prions. Uranyl oxalate is complexed onto the crystal lattice of wild-type Mo and SHa PrP 27–30 (A and B) but not onto the crystal lattice of PrPSc106 (C). Uranyl phthalate cannot bind to the crystal lattice of either PrP 27–30 or PrPSc106 (D, E, and F). Bars represent 100 nm.

After studying the influence of the stability constants of various uranyl salts on complex formation [30], we then examined the effect of the size of the counter-ion. For these studies, we used uranyl phthalate, which has a pK of 4.4 [42] and a counter-ion volume of 522 Å3, considerably larger than those of oxalate or acetate (Table 2), allowing us to probe the physical dimensions of the binding site. Interestingly, neither PrP 27–30 nor PrPSc106 was able to form complexes with uranyl phthalate (Figures 1D–1F), which provides only a very weak contrast. This observation suggests that the size of the counter-ion is an important factor in the formation of the uranyl–PrP complexes.

Table 2.

Uranyl complexation of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106.

| COMPLEX FORMATION WITH:‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uranyl salt | Stability constant* |

Counter-ion volume†(Å3) |

SHaPrP 27–30 | MoPrP 27–30 | MHM2 PrPSc106 |

| Uranyl acetate | 3.2 | 240 | 99 | 100 | 87 |

| Uranyl oxalate | 6.5 | 290 | 100 | 60 | ND¶ |

| Uranyl citrate | 18.9 | 541 | ND¶ | ND¶ | ND¶ |

| Uranyl phthalate | 4.4 | 522 | ND¶ | ND¶ | ND¶ |

To determine the size of the respective counter-ion, we calculated the accessible volume for each ion by starting with the accessible surface computed from the van der Waals radius by using the Voidoo program [48, 49].

Relative quantification of the uranyl ions bound to the center of the unit cell: we calculated the ratio between the total optical density within a unit cell and the density in the center only. The numbers were then normalized for each uranyl salt.

Not determined; quantification not possible, since complexation of uranyl ions was not observed.

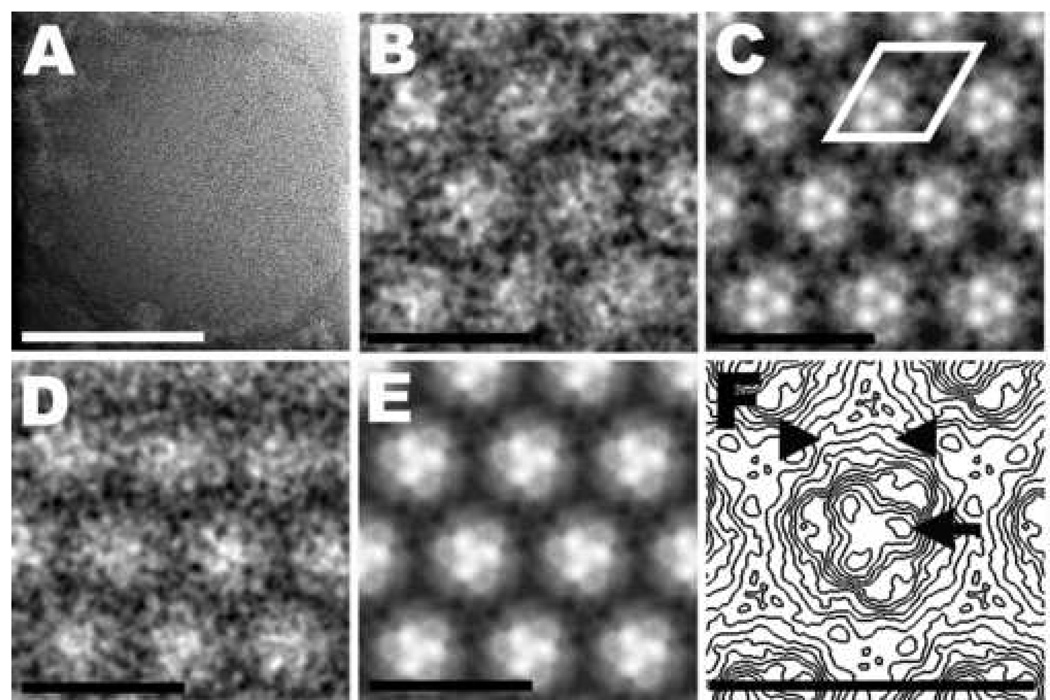

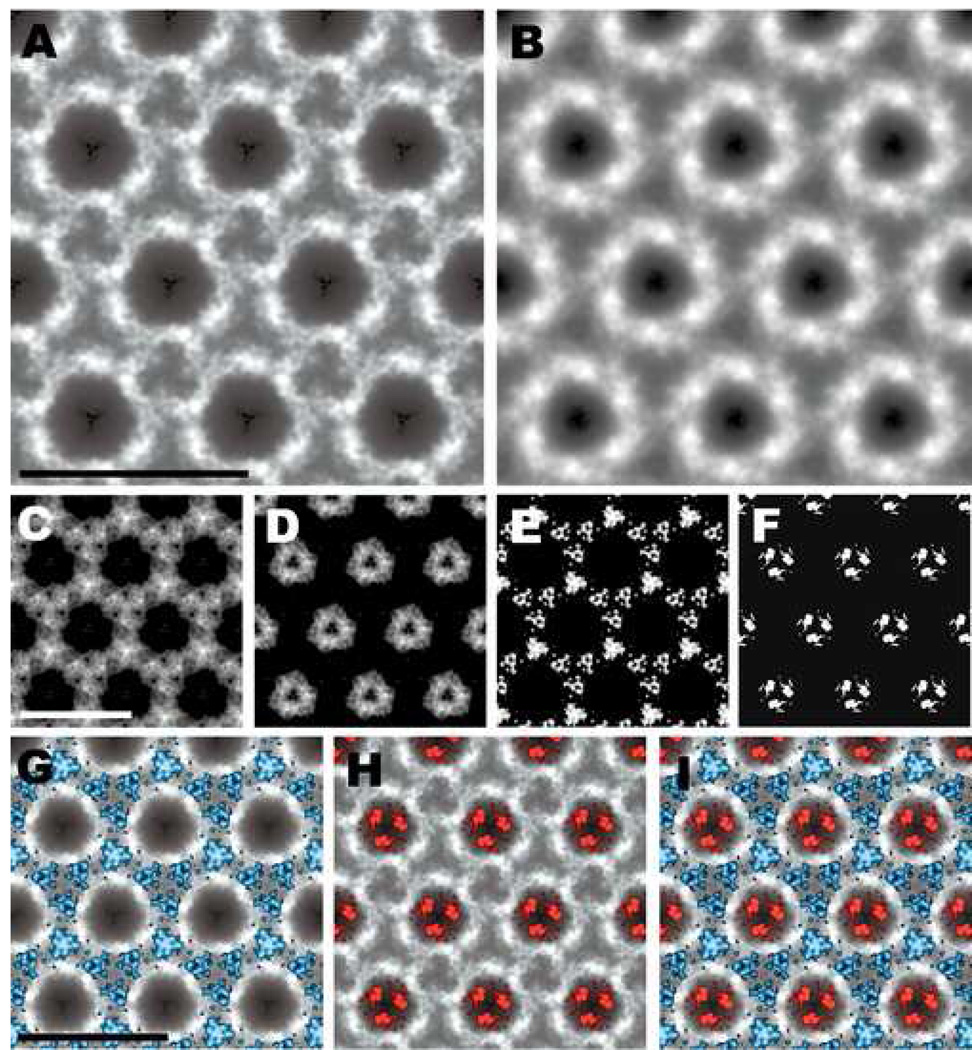

Ammonium molybdate was used as a negative stain for the crystals of both PrP 27–30 (data not shown) and PrPSc106 (Figure 2). The low contrast of this stain makes it difficult to recognize the 2D crystal lattice (Figures 2A), but image processing reveals a partially reversed contrast of the unit cells (Figures 2B and 2D) compared to uranyl acetate–stained specimens. The center of the unit cell contains three major, stain-excluding densities grouped around the center of the trimeric subunit (Figures 2C and 2E). These densities presumably are part of the protein moiety within the unit cell (Figure 2F, arrow). In addition, the presence of partial or full negative charges may repel the molybdate anions from the center region of the unit cell. The periphery of the subunit shows numerous densities, some of which correlate with the densities of the N-linked oligosaccharides (Figure 2F, arrowheads) as previously determined by difference mapping between uranyl acetate–stained PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 [30].

Fig. 2.

Ammonium molybdate–stained 2D crystal of MHM2 PrPSc106 and image-processing results. (A) Raw image of a 2D crystal. The low contrast makes it difficult to see the regularity of the crystal lattice. (B) High magnification view of a correlation average. Dark areas indicate the presence of the heavy-metal stain; light areas correspond to protein or carbohydrate density. (C) Crystallographic average obtained from the correlation average. The regions occupied by heavy-metal stain and protein or carbohydrate density have become much clearer. A unit cell, with dimensions of 6.9 nm (a=b) and γ = 120°, is outlined in white. (D) High magnification view of a group average obtained from three independent correlation averages. (E) Group average of three independent crystallographic averages. (F) Contour map of an enlarged unit cell taken from panel (E). The arrow points toward one of three stain-excluding densities that presumably represent a part of the protein moiety of PrP 27–30. The arrowheads indicate densities that correlate with the presumed position of the N-linked oligosaccharides. Bar in (A) represents 100 nm; bars in (B, C, D, E, F) represent 10 nm.

Noticeably, the apparent resolution of the image processing results from the ammonium molybdate–stained crystals is somewhat lower than the results of the uranyl acetate–stained specimens. The image-processing algorithm is very sensitive to the amount of contrast and the low contrast of the ammonium molybdate–stained 2D crystals greatly reduces the processing efficiency. The lower quality of the 2D crystals of mouse (Mo) PrP 27–30 prevented the image-processing algorithm from converging, thereby rendering the results of the iterative procedure useless (data not shown). Only the higher quality crystals of MHM2 PrPSc106 allowed the image-processing algorithm to converge, yielding interpretable results (Figure 2). This unfortunately prevented us from calculating difference maps between ammonium molybdate–stained crystals of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 and to compare them with difference maps obtained from uranyl acetate–stained crystals (see below).

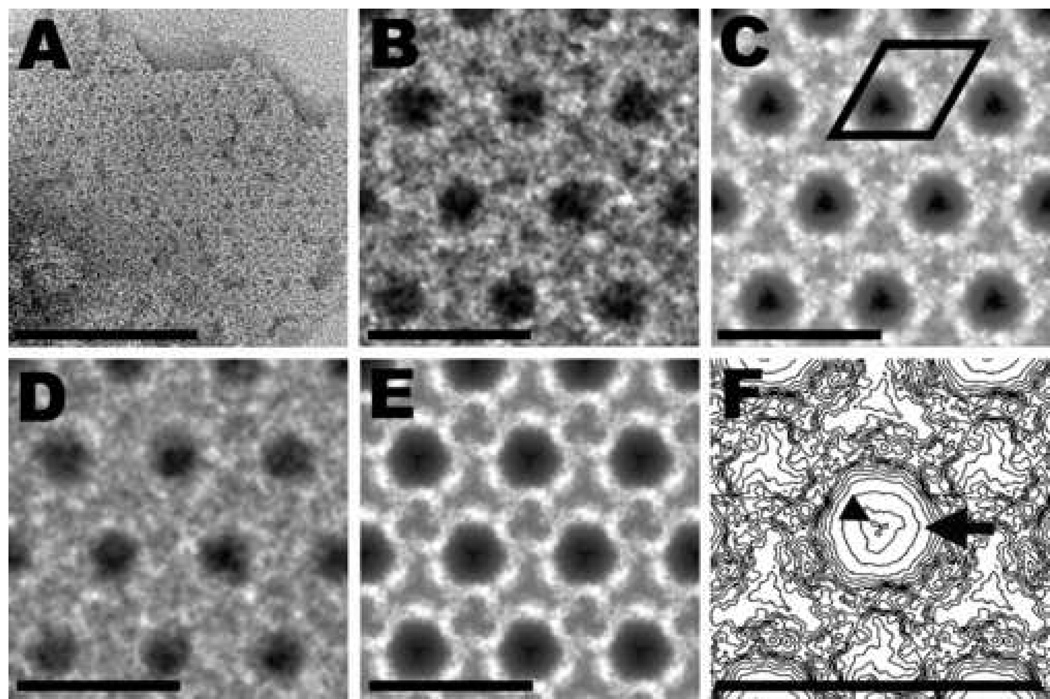

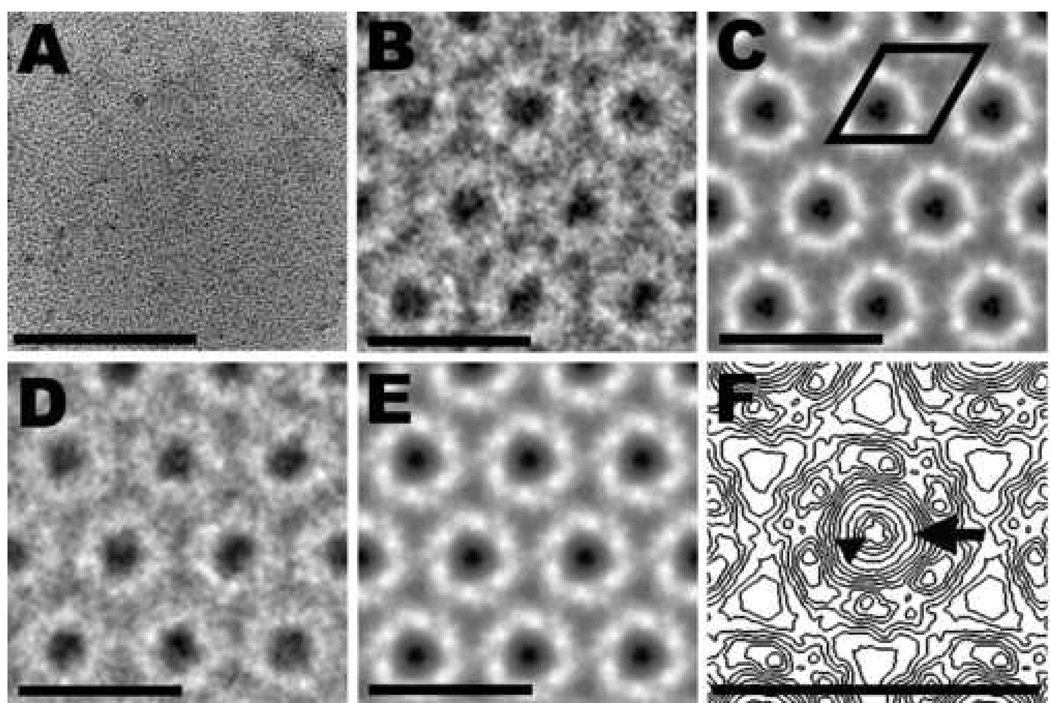

Improved images of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106

We previously published electron micrographs of 2D crystals of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106; these micrographs were obtained with a Jeol JEM 100 CX II electron microscope [30]. The technical limitations of the electron microscope restricted the quality of the electron micrographs. In addition, the relatively low quality of these 2D crystals prevented us from using low-dose, cryo-imaging techniques. The 2D crystals of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 were relatively small, contained numerous holes, and the lattices were bent (Figures 3A and 4A, respectively). We revisited these 2D crystals using a state-of-the-art electron microscope (FEI Tecnai F20). Imaging the 2D crystals with a more coherent, field-emission gun-derived, 200-kV electron beam enabled us to visualize additional molecular details.

Fig. 3.

Uranyl acetate–stained 2D crystal of MoPrP 27–30 and image-processing results. (A) Raw image of a 2D crystal. (B) High magnification view of the final correlation average. Very dark areas (in the center of the unit cell) indicate the presence of many, tightly bound uranyl ions (positive staining); intermediate gray areas represent unspecific binding by uranyl ions (negative staining); light areas correspond to protein or carbohydrate density. (C) Crystallographic average obtained from the correlation average. The regions occupied by heavy-metal stain and protein or carbohydrate density have become much clearer. A unit cell, with dimensions of 6.9 nm (a=b) and γ = 120°, is outlined in black. (D) High magnification view of a group average obtained from three independent correlation averages. (E) Group average of three independent crystallographic averages. (F) Contour map of an enlarged unit cell taken from panel (E). The arrow points toward the center of the trimeric subunit where many uranyl ions bound to the crystal lattice of PrP 27–30. Distinct densities of uranyl ions were seen in three symmetrically arranged positions, one of which is indicated by the arrowhead. Bar in (A) represents 100 nm; bars in (B, C, D, E, F) represent 10 nm.

Fig. 4.

Uranyl acetate–stained 2D crystal of MHM2 PrPSc106 and image-processing results. (A) Raw image of a 2D crystal. (B) High magnification view of the final correlation average. Very dark areas (in the center of the unit cell) indicate the presence of many, tightly bound uranyl ions (positive staining); intermediate gray areas represent unspecific binding by uranyl ions (negative staining); light areas correspond to protein or carbohydrate density. (C) Crystallographic average from the correlation average. The regions occupied by heavy-metal stain and protein or carbohydrate density have become much clearer. A unit cell, with dimensions of 6.9 nm (a=b) and γ = 120°, is outlined in black. (D) High magnification view of a group average obtained from three independent correlation averages. (E) Group average of three independent crystallographic averages. (F) Contour map of an enlarged unit cell taken from panel (E). The arrow points toward the center of the trimeric subunit where many uranyl ions bound to the crystal lattice of PrPSc106. Distinct densities of uranyl ions were seen in three symmetrically arranged positions. One of these densities is indicated by the arrowhead, but the contour map does not fully resolve the distinct densities. Bar in (A) represents 100 nm; bars in (B, C, D, E, F) represent 10 nm.

The center of the unit cell showed enhanced structural detail apparently due to the higher penetrating power of the electron beam (Figures 3C, 3E, 3F, 4C, 4E and 4F). Previously, the uranyl ions that bind in the center of the unit cell apparently caused inelastic and multiple scattering of the electrons, which severely limited the amount of structural information in the electron micrographs [30]. The 200-kV electron beam reduced these unwanted effects substantially, but residual blurring at the center region was still noticeable, as demonstrated by the lack of distinct features in the center of the subunits (Figures 3F and 4F, arrows).

In addition to higher-resolution electron micrographs, we improved the image-processing routines. The iterative correlation-mapping and -averaging procedures enhanced the quality of the crystal images considerably (Figures 3B and 4B). To increase the detail further, we employed crystallographic analysis and averaging. Crystallographic analysis indicated a p3 plane group symmetry for the 2D crystals (Table 1). Therefore, a p3 symmetry was applied to all images during crystallographic averaging (Figures 3C and 4C). To obtain a final average, group averages were determined from the correlation and crystallographic averages from three independent 2D crystals of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106, respectively (Figures 3D and 3E, 4D and 4E, respectively). These pictures show substantially more detail than was evident in our earlier study [30]. Distinct densities for the protein and carbohydrate moieties could be discerned (in light gray or white). Under these imaging conditions, the uranyl ions show a highly concentrated and specific binding pattern on the 2D crystal lattice as demonstrated by the pronounced, dark spots in the center of the unit cell (Figures 3F and 4F, arrowheads).

Difference mapping

The N-terminus of PrP106 was engineered to start at residue 89 (Mo numbering), the same residue at which the most prevalent form of MoPrP 27–30 begins. MHM2 PrPSc106 differs from MoPrP 27–30 in three respects: (i) it lacks residues 141–176 and (ii) it is almost exclusively diglycosylated whereas PrP 27–30 is a mixture of di-, mono-, and unglycosylated forms (iii) the sequence differs at two residues: 108 and 111 [31, 32]. MHM2 PrPSc106 has methionine residues at positions 108 and 111, which create an epitope that is recognized by the 3F4 monoclonal antibody (mAb) [31, 44, 45]. The 3F4 epitope is buried in native PrPSc but exposed in PrPC [28, 46].

Subtraction maps between PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 produced higher-resolution difference maps and revealed a number of notable features (Figures 5C and 5D), most of which proved to be statistically significant (Figures 5E and 5F). The difference signals attributed to the N-linked oligosaccharides (Figure 5E) were contiguous, in contrast to those described earlier in which such densities were quite scattered [30]. The difference signal ascribed to the missing peptide density of the internal deletion was similar to that reported previously (Figure 5F). The combined difference maps for the N-linked oligosaccharides and the internal deletion of PrP106 are shown in Figures 5G–I.

Fig. 5.

Difference maps between PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106. (A and B) Crystallographic averages of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106, respectively (compare Figs. 3E and 4E). (C) Map of the difference of [(PrP 27–30) – (PrPSc106)]. (D) Map of the difference of [(PrPSc106) – (PrP 27–30)]. (E and F) Statistically significant differences (in white) between (A) and (B) calculated by subtracting three times the standard error from the respective subtraction maps (C and D). (G) The statistically significant difference from panel E overlaid onto the PrP 27–30 projection map (A) localizes the N-linked sugars. (H) The statistically significant difference from panel F overlaid onto the PrP 27–30 projection map localizes the internal deletion of PrPSc106 (A). (I) The statistically significant differences from panels E (blue) and F (red) overlaid onto the PrP 27–30 projection map (A). Bar in (A) represents 10 nm and also applies to panel (B); bar in (C) represents 10 nm and also applies to panels (D) through (F); bar in (G) represents 10 nm and also applies to panels (H) and (I).

Native PrP 27–30 forms the 2D crystals

Numerous experiments indicate that the 2D crystals described in our current and previous studies [30, 47] contain native and fully infectious PrP 27–30. We base this conclusion on (i) immuno-gold labeling experiments and (ii) the high titers of prion infectivity determined by bioassays in wild-type or transgenic mice.

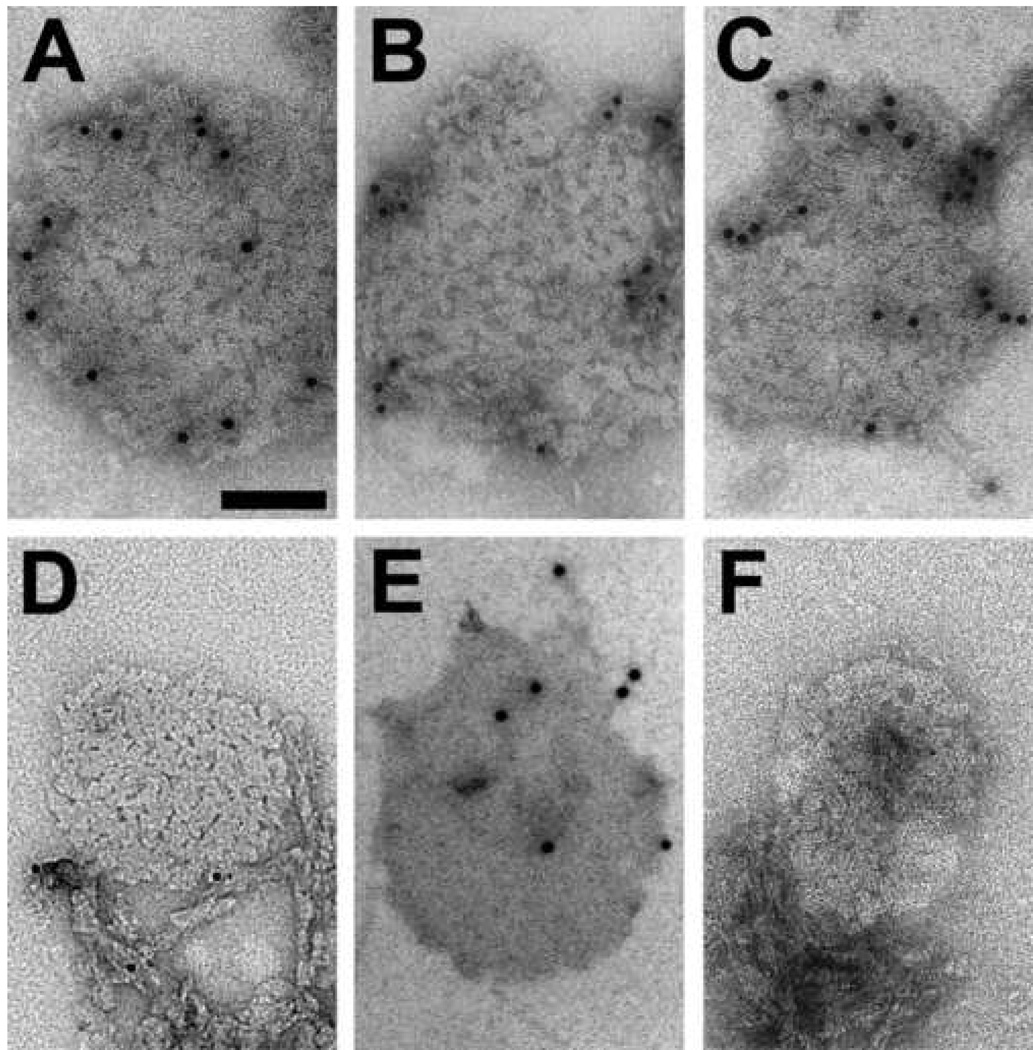

Immuno-gold labeling with the anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies R1, R2, 28D, and 3F4 (Figures 6A–E) established that PrP is an integral constituent of the 2D crystals. The antibodies R1 and R2 recognize residues 225–231 [28]. Antibody 3F4 binds in the region of residues 104–113 [44, 45], which is accessible in PrPC and denatured PrP but buried in PrPSc [28, 46]. The epitope of 28D has not been mapped [36]. Decoration with the 3F4 antibody could only be achieved after urea denaturation (Figure 6D and 6E), demonstrating that samples contained PrPSc. Generally, the labeling density for all antibodies may appear to be low (Figure 6A–C, and 6E), but it is not uncommon to encounter low labeling densities when trying to immuno-label tightly packed structures such as 2D crystals. Controls lacking the primary antibody showed very little, unspecific background labeling (Figure 6F).

Fig. 6.

Immunolabeling of PrP 27–30 2D crystals with different anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies: R1 (A), R2 (B), 28D (C), and 3F4 (D and E). The 2D crystals did not label with 3F4 (D) unless the samples were denatured with 2 M urea (E), which invariably obliterated the crystal lattice. (F) Immunolabeling control without primary antibody. Virtually no gold particles were found on the 2D crystals or prion rods, demonstrating the specificity of the antibody labeling (A–E). Bar in (A) represents 100 nm and applies to all panels.

Furthermore, the 2D crystals originate in preparations that have very high titers of infectivity. The preparation shown in Figures 1A and 1D had a titer of 9.2 log ID50/ml at a total protein concentration of 11.2 µg/ml. The preparation that was used for Figures 1B, 1E, and 3 had a titer of 7.5 log ID50/ml at a total protein concentration of 14.7 µg/ml. Currently, we are unable to determine the precise titers of the PrPSc106 preparations (Figures 2 and 4), since we have not yet calibrated the incubation period assay for this particular construct and this line of transgenic mice [32]. Throughout this study, the samples were not treated with denaturing or otherwise harsh agents (except Figure 6D), which argues that the titers measured by bioassay were maintained in our samples and that the PrP 27–30 (and presumably PrPSc106) within the 2D crystals are fully infectious.

DISCUSSION

By using different heavy metal salts, we investigated the structure of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106. We report here the effects of different counter-ions on the binding of uranyl ions to the 2D crystal lattices of PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106. Previously, we observed that PrP 27–30 could bind both uranyl acetate and uranyl oxalate, despite their substantially different stability constants (Table 2). Extending our analysis to PrPSc106, we discovered that the redacted protein could not bind uranyl oxalate (Figure 1C). Because PrPSc106 lacks most of the negatively charged residues of PrP 27–30, it apparently cannot compete with the complexing strength of the oxalate anion. In contrast to the oxalate anion, the considerably weaker acetate anion was apparently displaced by PrPSc106 (Figure 4 and Table 2). This observation gave us a second, independent method by which to localize the internal deletion of PrP106 to the center region of the trimeric oligomer, in good agreement with the results of our earlier approach that used difference mapping between PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Localization of the N-linked oligosaccharides and the internal deletion of PrP106.

| Localization method | Residues 141–176 | N-linked sugars |

|---|---|---|

| Difference mapping*† | Projection map of PrP 27–30 minus projection map of PrPSc106 | Projection map of PrPSc106 minus projection map of PrP 27–30 |

| Labeling / staining | Differential staining with uranyl oxalate† | Specific labeling with Monoamino Nanogold followed by difference mapping* |

Published in [30].

This study.

The higher resolution projection maps which we obtained for uranyl acetate–stained PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 clearly show the uranyl ions concentrated in three spots near the center of the unit cell (Figures 3E and 4E). Within the framework of our molecular model for the structure of PrP 27–30 [47], this location would indicate a binding of uranyl ions to the β-helical region of the molecule. The model shows a tightly packed interface between the three β-helices. Therefore, the size of the counter-ion could influence the complexation of the uranyl ions to the 2D crystal lattice as steric constrains might restrict access of large ions. We tested uranyl phthalate, which has a considerably larger counter-ion than uranyl acetate or uranyl oxalate but has an intermediate stability constant (Table 2). Interestingly, uranyl phthalate could not bind to the PrP molecules in the crystal lattice, indicating that the size of the anion is an important factor in determining the binding properties of heavy metal stains (Figures 1D–1F). Furthermore, the low contrast obtained with uranyl phthalate indicates that most of the details in the uranyl acetate–stained specimens are affected by the complexation of uranyl ions.

The trimeric model for the structure of PrP 27–30 [47] can provide an additional explanation for at least some of the tightly bound uranyl ions: exposed at the corners of the proposed β-helices that face the center of the trimer, backbone carbonyls are in close proximity to polar side chains from a neighboring monomer. In principle, this configuration provides a suitable arrangement to coordinate uranyl ions within the trimer, at locations that correspond to the high electron densities observed in the center of the unit cell (Figures 3, 4, and 5). For uranyl acetate, the coordination of uranyl ions can be accomplished by substituting either one or two acetate counter-ions as well as bound water molecules for the polar moieties (carbonyl groups and polar side chains) of the trimer. Consequently, the ability of uranyl ions to bind the 2D crystal depends both on the dissociation constant and size of the counter-ion. The size of the counter-ion may be a factor related to steric hindrance that could prevent binding in the crowded center of the β-helical trimer. However, this interpretation cannot account entirely for the observed differences in uranyl oxalate binding to PrP 27–30 and PrPSc106 (Figure 1 and Table 2). Clearly, residues 141–176 exert substantial influence on the complexation of the uranyl ions, because this deletion (which encompasses five negatively charged residues) results in the loss of binding of uranyl oxalate.

The densities around the center of the unit cell that became apparent by staining with ammonium molybdate (Figure 2) coincide with the location of the proposed β-helices. The negatively charged residues that presumably contribute to the complexation of uranyl cations would also repel the molybdate anions from these structures, thereby heightening their apparent density. A more detailed analysis how these experimental data fit with the various models that were proposed for the structure of PrP 27–30 will be published elsewhere (Wille et al., manuscript in preparation).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David A. Agard (UCSF) for his advice on various practical aspects of electron microscopy and image processing and his critical reading of the manuscript. Furthermore, we thank Gatan Inc. for the temporary loan of a Gatan 694 Slow-Scan CCD camera. C.G. was supported by fellowships from the Belgian American Educational Foundation and the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG02132, AG021601, and AG10770), generous support from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation, and a gift from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation. F.E.C. and S.B.P. have financial interest in InPro Biotechnology, Inc.

Abbreviations

- CTF

contrast transfer function

- FTIR

Fourier-transform infrared

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

normal cellular isoform

- PrPSc

disease-causing isoform

- PrP 27–30

N-terminally truncated PrPSc

- PrPSc106

miniprion of 106 residues

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prusiner SB. Prions. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 3059–3092. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legname G, Baskakov IV, Nguyen H-OB, Riesner D, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Synthetic mammalian prions. Science. 2004;305:673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1100195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan K-M, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Huang Z, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Conversion of a-helices into b-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:10962–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan K-M, Stahl N, Prusiner SB. Purification and properties of the cellular prion protein from Syrian hamster brain. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1343–1352. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wille H, Prusiner SB. Ultrastructural studies on scrapie prion protein crystals obtained from reverse micellar solutions. Biophys. J. 1999;76:1048–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77270-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govaerts C, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Structural studies of prion proteins. In: Prusiner SB, editor. Prion Biology and Diseases. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. pp. 243–282. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Billeter M, Glockshuber R, W�thrich K. NMR structure of the mouse prion protein domain PrP(121–231) Nature. 1996;382:180–182. doi: 10.1038/382180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donne DG, Viles JH, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, James TL, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein PrP(29–231): the N terminus is highly flexible. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:13452–13457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James TL, Liu H, Ulyanov NB, Farr-Jones S, Zhang H, Donne DG, Kaneko K, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Solution structure of a 142-residue recombinant prion protein corresponding to the infectious fragment of the scrapie isoform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:10086–10091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riek R, Hornemann S, Wider G, Glockshuber R, W�thrich K. NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein, mPrP(23–231) FEBS Lett. 1997;413:282–288. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00920-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Farr-Jones S, Ulyanov NB, Llinas M, Marqusee S, Groth D, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, James TL. Solution structure of Syrian hamster prion protein rPrP(90–231) Biochemistry. 1999;38:5362–5377. doi: 10.1021/bi982878x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López García F, Zahn R, Riek R, W�thrich K. NMR structure of the bovine prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:8334–8339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahn R, Liu A, L�hrs T, Riek R, von Schroetter C, López García F, Billeter M, Calzolai L, Wider G, Wüthrich K. NMR solution structure of the human prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:145–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calzolai L, Lysek DA, Perez DR, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Prion protein NMR structures of chickens, turtles, and frogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:651–655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408939102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gossert AD, Bonjour S, Lysek DA, Fiorito F, Wuthrich K. Prion protein NMR structures of elk and of mouse/elk hybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:646–650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409008102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lysek DA, Schorn C, Nivon LG, Esteve-Moya V, Christen B, Calzolai L, von Schroetter C, Fiorito F, Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wuthrich K. Prion protein NMR structures of cats, dogs, pigs, and sheep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:640–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408937102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornemann S, Schorn C, Wuthrich K. NMR structure of the bovine prion protein isolated from healthy calf brains. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knaus KJ, Morillas M, Swietnicki W, Malone M, Surewicz WK, Yee VC. Crystal structure of the human prion protein reveals a mechanism for oligomerization. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eghiaian F, Grosclaude J, Lesceu S, Debey P, Doublet B, Treguer E, Rezaei H, Knossow M. Insight into the PrPC-->PrPSc conversion from the structures of antibody-bound ovine prion scrapie-susceptibility variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:10254–10259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400014101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haire LF, Whyte SM, Vasisht N, Gill AC, Verma C, Dodson EJ, Dodson GG, Bayley PM. The crystal structure of the globular domain of sheep prion protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:1175–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prusiner SB, McKinley MP, Bowman KA, Bolton DC, Bendheim PE, Groth DF, Glenner GG. Scrapie prions aggregate to form amyloid-like birefringent rods. Cell. 1983;35:349–358. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glenner GG, Eanes ED, Bladen HA, Linke RP, Termine JD. Beta-pleated sheet fibrils - a comparison of native amyloid with synthetic protein fibrils. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1974;22:1141–1158. doi: 10.1177/22.12.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caughey BW, Dong A, Bhat KS, Ernst D, Hayes SF, Caughey WS. Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27–30 in water by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7672–7680. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasset M, Baldwin MA, Fletterick RJ, Prusiner SB. Perturbation of the secondary structure of the scrapie prion protein under conditions that alter infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:1–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safar J, Roller PP, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr Conformational transitions, dissociation, and unfolding of scrapie amyloid (prion) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:20276–20284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wille H, Zhang G-F, Baldwin MA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Separation of scrapie prion infectivity from PrP amyloid polymers. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;259:608–621. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen JT, Inouye H, Baldwin MA, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Kirschner DA. X-ray diffraction of scrapie prion rods and PrP peptides. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;252:412–422. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peretz D, Williamson RA, Matsunaga Y, Serban H, Pinilla C, Bastidas RB, Rozenshteyn R, James TL, Houghten RA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Burton DR. A conformational transition at the N-terminus of the prion protein features in formation of the scrapie isoform. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;273:614–622. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paramithiotis E, Pinard M, Lawton T, LaBoissiere S, Leathers VL, Zou WQ, Estey LA, Lamontagne J, Lehto MT, Kondejewski LH, Francoeur GP, Papadopoulos M, Haghighat A, Spatz SJ, Head M, Will R, Ironside J, O'Rourke K, Tonelli Q, Ledebur HC, Chakrabartty A, Cashman NR. A prion protein epitope selective for the pathologically misfolded conformation. Nat. Med. 2003;9:893–899. doi: 10.1038/nm883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wille H, Michelitsch MD, Guénebaut V, Supattapone S, Serban A, Cohen FE, Agard DA, Prusiner SB. Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein by electron crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:3563–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052703499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muramoto T, Scott M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Recombinant scrapie-like prion protein of 106 amino acids is soluble. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:15457–15462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Supattapone S, Bosque P, Muramoto T, Wille H, Aagaard C, Peretz D, Nguyen H-OB, Heinrich C, Torchia M, Safar J, Cohen FE, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Scott M. Prion protein of 106 residues creates an artificial transmission barrier for prion replication in transgenic mice. Cell. 1999;96:869–878. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudd PM, Merry AH, Wormald MR, Dwek RA. Glycosylation and prion protein. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:578–586. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prusiner SB, Bolton DC, Groth DF, Bowman KA, Cochran SP, McKinley MP. Further purification and characterization of scrapie prions. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6942–6950. doi: 10.1021/bi00269a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leffers KW, Wille H, Stohr J, Junger E, Prusiner SB, Riesner D. Assembly of natural and recombinant prion protein into fibrils. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:569–580. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson RA, Peretz D, Pinilla C, Ball H, Bastidas RB, Rozenshteyn R, Houghten RA, Prusiner SB, Burton DR. Mapping the prion protein using recombinant antibodies. J. Virol. 1998;72:9413–9418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9413-9418.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J. Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hovmöller S. CRISP: Crystallographic image processing on a personal computer. Ultramicroscopy. 1992;41:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crepeau RH, Fram EK. Reconstruction of imperfectly ordered zinc-induced tubulin sheets using cross-correlation and real space averaging. Ultramicroscopy. 1981;6:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3991(81)80173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank J. New methods for averaging non-periodic objects and distorted crystals in biologic electron microscopy. Optik. 1982;63:67–89. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frank J, Radermacher M, Penczek P, Zhu J, Li Y, Ladjadj M, Leith A. SPIDER and WEB: Processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;116:190–199. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martell AE, Smith RM. Critical stability constants, ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganesh R, Robinson KG, Reed GD, Sayler GS. Reduction of hexavalent uranium from organic complexes by sulfate- and iron-reducing bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:4385–4391. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4385-4391.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers M, Serban D, Gyuris T, Scott M, Torchia T, Prusiner SB. Epitope mapping of the Syrian hamster prion protein utilizing chimeric and mutant genes in a vaccinia virus expression system. J. Immunol. 1991;147:3568–3574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanyo ZF, Pan K-M, Williamson A, Burton DR, Prusiner SB, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE. Antibody binding defines a structure for an epitope that participates in the PrPC ->PrPSc conformational change. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:855–863. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Eight prion strains have PrPSc molecules with different conformations. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Govaerts C, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Evidence for assembly of prions with left-handed β-helices into trimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:8342–8347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402254101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleywegt GJ. Detection, delineation, measurement and display of cavities in macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:178–185. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993011333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kleywegt GJ, Zou J-Y, Kjeldgaard M, Jones TA. Around O. In: Rossman MG, Arnold E, editors. Crystallography of biological macromolecules. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]