Abstract

The cognitive function of breast cancer survivors (BC, n = 52) and individually-matched healthy controls (n = 52) was compared on a battery of sensitive neuropsychological tests. The BC group endorsed significantly higher levels of subjective memory loss and scored significantly worse than controls on learning and delayed recall indices from the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT). Defining clinically significant impairment as scores at or below the 7th percentile of the control group, the rate of cognitive impairment in the BC sample was 17% for total learning on the AVLT, 17% for delayed recall on the AVLT, and 25% for either measure. Findings indicate that a sizeable percentage of breast cancer survivors have clinically significant cognitive impairment.

Keywords: breast cancer, neuropsychological test, memory, cognition, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Up to 83% of breast cancer survivors report some form of subjective cognitive dysfunction (Jenkins et al., 2006). A recent meta-analysis of seven studies and over 300 breast cancer survivors indicated that survivors, as a group, showed lower performance on objective tests of cognitive function relative to controls; however, the effect sizes were in the small to medium range (Stewart et al., 2006) suggesting that while cognitive complaints may be ubiquitous, the severity of the cognitive dysfunction may be less striking.

Our interest is in documenting the frequency of clinically significant cognitive dysfunction among breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer is the most prevalent form of cancer among women (accounts for 28% of all cancers (Black et al., 1997) and it has a relatively high survival rate (e.g., about 90% across all types [localized and regional] and all ages (Capocaccia et al., 1990; Chu et al., 1996)). In this context, even if residual cognitive impairment is relatively infrequent, these problems will affect large numbers of women. Therefore, it is critically important to generate accurate estimates of the rate of clinically significant cognitive impairment in this large cohort of survivors.

The range of potential mechanisms underlying cognitive function in breast cancer patients are many including: host factors (immune response to cancer, genetic variability in metabolic processes, and physiologic variability in oxidative and inflammatory reactivity), disease factors (cancer type and staging), treatment factors (exposure to surgical, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormone interventions), and interactions of these factors, for example see (Ahles & Saykin, 2007;Vardy, et al., 2008 ). Since multiple pathways to cognitive dysfunction may exist in this group, it is reasonable to attempt to understand the frequency of clinically significant impairments in all survivors as an initial first step.

The critical issue here is to fully understand the frequency of serious deficits in individual patients. In this area, cut-off scores denoting normal versus impaired performance are defined in relation to some reference standard. When approached from this perspective, the rate of clinically significant cognitive impairment among breast cancer survivors varies considerably according to the type of reference sample used to define impairment (e.g. published norms versus a recruited control group). For example, a study comparing survivors to published norms for cognitive performance found that 75% of the survivor sample met criteria for cognitive impairment (Wieneke & Dienst, 1995). One limitation inherent in using published norms as the criterion is that a demographic mismatch between the patient sample and the published reference norms could well be the source for diverging cognitive levels as opposed to breast cancer status per se. Even if the samples appear to be comparable, there may be differences in how the samples are constituted in terms of the clustering of individual demographic variables (e.g., age, education) within a sample. Further, there may be important differences between how tests are administered for the normative project versus the research study (e.g., differences in the number and types of other tests administered and the order of these tests). Differences along these dimensions confound results making it difficult to ascribe impairment unambiguously to the critical health factor under study - in this case breast cancer status.

Studies using recruited control groups are in a better position to examine the role of disease status on cognition. A recent study using a healthy control group as a reference standard found that between about 10-22% of breast cancer survivors had clinically significant cognitive impairments six months after primary cancer therapy (Schagen et al., 2006); however, there was a significant difference in age between the controls and the cancer patients and this could have contributed to the findings. In addition, while a large battery of tests was used, the rates of impairment by test were not reported making it difficult to determine which cognitive domains were more or less affected in the breast cancer survivors. Another recent study compared rates of cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients and demographically-matched healthy controls (Fan et al., 2005) using a screening test immediately after chemotherapy and at 1 and 2 year follow-up. Patients had significantly higher rates of moderate to severe impairment compared to controls initially (16% versus 5%, respectively) and at 1 year follow-up (4.4% vs. 3.6%, respectively); however, the screening test uses an algorithm to establish impairment and performance patterns in the screening domains were not reported making it difficult to determine which cognitive domains were more or less affected.

In this study, we individually-matched healthy controls to breast cancer survivors on age and education and administered a brief battery of sensitive cognitive tests and self-report measures of mood and cognition. We define clinically significant impairment on the basis of the healthy control performance and report on the rate of impairment in the breast cancer sample by individual test.

METHOD

Sample

The subjects in this project were part of another study that demonstrated the comparability of telephone-versus in-person neuropsychological assessment (Unverzagt et al., 2007). The study was approved by and subject to ongoing review by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. All participants gave written informed consent.

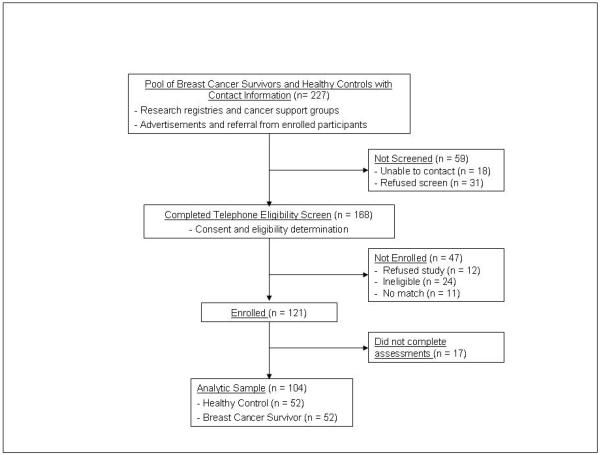

Participants were recruited from research registries, cancer support groups, advertisements posted in local churches and community centers, and by referral from enrolled participants. Breast cancer survivors were eligible for the study as follows: a) at least one-year after completion of primary cancer therapy (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) for breast cancer with no self-reported history of cancer relapse, metastatic disease, other cancer diagnosis except for participants with a history of non-metastatic skin cancer who received only local surgical treatment; b) female gender; c) age 40 years or older; and d) absence of self-reported history of major medical, neurologic, or psychiatric illness (i.e., absence of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, learning disability, head injury with loss of consciousness more than 60 minutes, epilepsy, stroke, brain tumor, brain infection, or brain degeneration). Healthy controls met the same eligibility criteria as BC participants except there had to be an absence of self-reported history of cancer (excepting skin cancer). In addition, HC were individually matched to BC participants on age (+/− 5 years) and education (+/− 3 years). A total of 227 women were identified for initial screening and 59 were not screened (18 unable to contact and 31 refused). 168 women completed the eligibility screen and 121 were enrolled (12 refused, 24 were ineligible, and 11 had no demographic match). 17 of the enrolled subjects did not complete all aspects of the assessment leaving 52 breast cancer survivors and 52 individually-matched healthy controls in this analytic sample.

Design and Procedure

Upon completion of the eligibility screening, participants were scheduled for an appointment at the research center. Upon arrival at the center, participants gave written informed consent and were randomly assigned to one of four conditions. Each subject was administered the same neuropsychological test battery (see below) on two occasions separated by one week in the research clinic by experienced and certified research technicians. Subjects were randomly assigned, stratified by breast cancer status, to one of four conditions: 1) to have the battery administered in-person on both occasions, 2) over the telephone on both occasions, 3) via telephone at Time 1 and in-person at Time 2, or 4) in-person at Time 1 and via telephone at Time 2. Participants were paid $25 for each appointment ($50 total).

The neuropsychological test battery was individually administered by trained and experienced psychometricians in an office in the research center. When a telephone administration format was used, the subject was placed in an office in the research center and the psychometrician called the subject over a hardwired telephone line using standard business-grade telephones. Before telephone assessments, subjects were given stimulus sheets (Symbol Digit form and self-report response options) and instructed to keep these sheets nearby during the call. They were told not to mark or write on the forms at any time. All test instructions were presented to the subject by the examiner over the telephone. Subjects provided verbal responses over the telephone to the examiner who then entered responses onto to typical clinical record forms.

At the conclusion of each assessment, the examiner made ratings of the subject’s hearing, comprehension, and behavioral and attitudinal response to testing on Likert scales. Each assessment was also coded for validity on a three-point scale (adequate, borderline, inadequate) using clinical judgment based on quality of the examination (e.g., telephone connection, extraneous noises, interruptions) and subject characteristics (e.g., hearing, confusion, abnormal motivation or effort, and abnormal events such as sounds of writing or perfect serial order responding on word list recall). Motivation and effort were rated according to the subject’s general cooperativeness which was captured, in part, by how readily the subject abandoned tasks and expressed negative emotions (e.g., frustration, anger, hopelessness).

Results indicated that a telephone administration format captured cognitive test scores (and self-reported mood and memory ratings) as reliably and precisely as traditional in-person assessment. Specifically, test–retest correlations, standard error of measurement, practice effects, and mean scores were similar whether obtained via in-person examination or over the telephone.

For this study, we used only data gathered from the Time 1 assessment collapsed across administration format as our prior study (Unverzagt et al., 2007) indicated that there was no affect of administration format on cognitive test performance.

The cancer history of BC participants was obtained by self-report including: age at diagnosis, stage of disease, estrogen and progesterone receptor status of the tumor, menopausal status, type of surgical treatment, and presence or absence of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy.

Instruments

The assessment battery took about 35 minutes to complete and included the following tests (in order of administration). Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) (Rey, 1941), a 15-item, 5-trial word list learning task in which Sum Recall is the total number of words recalled across all five learning trials, and Delayed Recall is free recall of the list after completion of the remaining tests in the battery. Digit Span from the WAIS-III (Wechsler, 1997) requires verbal repetition of ever longer digit strings forward and then backward. Total score is the number of strings correctly recalled. Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Oral Response Version (Smith, 1982) requires decoding a series of symbols by verbally stating the number that should be paired with each symbol by reference to a constantly available legend or key. For the telephone administration format, participants were given a folder containing the Symbol Digit stimulus page before being left alone to await the examiner’s telephone call in the research assessment room. Participants were instructed not to open the folder until being prompted by the examiner. At the proper time during the assessment, participants were instructed to take the form out of the folder at which time the instructions were presented. The participant’s verbal responses into the telephone were recorded by the research technician. Controlled Oral Word Association (COWA) (Benton & Hamsher, 1989) is a test of executive function that requires the spontaneous production of words beginning with a given letter. Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; (Radloff, 1977) measures self-reported depression with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Finally, an adapted version of the Squire Self-Report Scale (SRS; (Squire & Zouzounis, 1988) assesses subjective perception of memory functioning. The SRS has 18-items in which participants compare themselves to “the average person” on a 9-point scale (1 = ‘Worse than the Average Person,’ 5 = ‘Same as the average person,’ and 9 = ‘Better than the Average Person’).

Statistical Analysis

We determined the frequency of clinically significant impairment on the cognitive tests by adapting the procedures of Rao and colleagues (Rao et al., 1991) such that raw scores at or below the 7th percentile (1.5 SD below the mean) of the HC group defined clinically significant impairment. Count and percent of impaired subjects within the BC group was cross tabulated by test. In addition, independent samples t-tests and chi-squares were used to compare BC and HC groups on demographic, cognitive, and self-report variables.

In a secondary analysis, we used analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) within the BC group, controlling for age, education, and format of test administration to examine the role of cancer treatment variables on measured cognitive performance. All variables were binary coded as present vs. absent except for time since completion of primary cancer therapy which was coded via median split (i.e., less than 4 years vs. 4 or more years).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The analytic data set included 104 female volunteers (52 HC and 52 BC). Nearly 85% were white (the rest were African American [14%] or biracial [1%]), average age was 58.6 (± 9.0) years, mean education was 14.9 (± 2.6) years, and just over 62% were married (the rest were divorced [15.4%], widowed [14.4%], never married [5.8%], or living as married [1.9%], see Table 1). There were no significant group differences in age, t(102) = 0.45, p = .65; education, t(102) = 0.11, p =.91; proportion of whites, χ2 (104) = 1.18, p =.28; or proportion of married participants, χ2 (104) = 0.37, p = .54.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of Healthy Control and Breast Cancer groups.

| Healthy Control (n = 52) |

Breast Cancer (n = 52) |

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (M, SD) | 59.0 | 9.0 | 58.2 | 9.2 | .53 |

| Education, years (M, SD) | 14.9 | 2.4 | 14.9 | 2.8 | .98 |

| Race | .46 | ||||

| White (n, %) | 42 | 80.8 | 46 | 88.5 | |

| Non-white (n, %) | 10 | 19.2 | 6 | 11.5 | |

| Marital Status | .80 | ||||

| Married | 31 | 59.6 | 34 | 65.4 | |

| Non-married | 21 | 40.4 | 18 | 34.6 | |

Most BC participants had early stage breast cancer (50% at Stage II or lower). Time since completion of primary therapy ranged from 1.2 to 15.8 years (M = 4.6, SD = 2.76). All had undergone surgery with approximately two thirds limited to lumpectomy. The majority had received radiation therapy (80.8%) and chemotherapy (55.8%). Almost 79% of the survivors were exposed to hormone therapy.

Group-level Comparisons in Cognition and Mood

The BC participants’ self-rated memory function was significantly below healthy controls on the Squire SRS (t[102] = 2.49, p = .014, see Table 2). The BC group also had significantly lower objectively-measured memory performance compared to healthy controls on AVLT Sum Recall (t[102] = 2.68, p = .009) and Delayed Recall (t[102] = 2.30, p = .023). There was a non-significant trend for BC participants to have lower verbal fluency on the COWA compared to the HC sample (t[102] = 1.77, p = .08). No significant group differences were observed on measures of attention (Digit Span) or processing speed (Digit Symbol, all p’s > .78). The effect size for each test is also displayed in Table 2. The effect sizes are in the small to moderate range with larger effects for the AVLT markers of new learning and delayed recall (.53 to .45) and verbal fluency (.35). Not shown in the table, there were no group differences in self-reported depressive symptoms on the CES-D (survivors group M = 10.8, SD = 8.1; healthy control group M = 9.5 SD = 8.2; t[102] = 0.82, p = .415).

Table 2.

Comparison of cognitive test scores for Healthy Controls (n = 52) and Breast Cancer Survivors (n = 52).

| Healthy Control |

Breast Cancer |

p | Effect Size |

Percent BC Sample Impairedb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| AVLT Sum Recall (41)a | 52.4 | 8.1 | 48.5 | 7.2 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 17 |

| AVLT Delayed Recall (6) |

10.9 | 2.8 | 9.6 | 2.8 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 17 |

| Digit Span (12) | 17.7 | 4.1 | 17.8 | 4.0 | 0.89 | −0.03 | 2 |

| Symbol Digit (39) | 54.1 | 10.4 | 53.6 | 8.2 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 6 |

| COWA (24) | 42.2 | 12.4 | 38.2 | 10.9 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 12 |

| Squire SRS (68) | 102.9 | 22.6 | 92.9 | 17.9 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 14 |

Note. BC = breast cancer survivor, AVLT = Auditory Verbal Learning Test; COWA = Controlled Oral Word Association; SRS = memory Self-report Scale.

Raw score corresponding to the 7th percentile (or 1.5 SD below the mean) of HC performance is listed in parentheses.

For each test, the frequency of impairment in the BC group was calculated as the percent of BC participants scoring below the 7th percentile (or 1.5 SD below the mean) of the HC distribution.

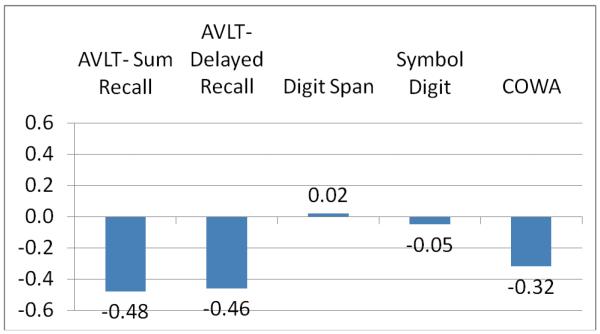

Figure 2 shows a plot of z-scores for the breast cancer survivors indexed on the controls ([mean BCS - mean HC]/SD of HC) for each test. This has the desirable effect of putting all scores on the same scale thus facilitating comparisons across tests. The largest effects are found on measures of memory and executive function.

Figure 2.

Plot of Z-score Transformed Test Scores in Breast Cancer Survivors (n = 52).

Note: AVLT = Auditory Verbal Learning Test; COWA = Controlled Oral Word

Frequencies of Clinically Significant Impairment

Clinically significant impairment was defined as a score at or below the 7th percentile of HC performance. Table 2 shows that 17% of the BC sample was classified as impaired on AVLT Sum Recall and 17% were clinically impaired on AVLT Delayed Recall. A total of 25% of the BC group was impaired on one or both of these indices. In the area of executive cognitive function, approximately 12% of BC sample had clinically significant impairment on the COWA.

A count of number of BC subjects who were impaired on the five major objectively-measured cognitive indices (AVLT Sum Recall, AVLT Delayed Recall, Digit Span Total, Symbol Digit, and COWA) revealed that 64% (33/52) had no scores at or below the 7th percentile of HC cut-off, 21% (11/52) had 1 test below cut-off, and 15% (8/52) had 2 or more indices below cut-off. This compares to 79% of the HC with no scores below cut-off, 13% with one score below cut-off, and 6% with 2 or more scores below cut-off.

Approximately 14% (7/52) of the BC sample self-reported clinically significant levels of memory impairment on the Squire SRS (i.e., score at or below the 7th percentile of HC, i.e., raw score of 68 or less). This subgroup of BC patients with significant complaints of memory loss did not perform significantly differently from non-complaining BC subjects on any of the objective cognitive measures nor in self-reported depressive symptoms (all p’s > .16). The same set of comparisons among healthy controls revealed a similar pattern of no difference between complainers (n = 4) and non-complainers (n = 48) on cognitive test performance. In the case of the HC, however, self-reported depressive symptoms were significantly more abundant in the HC with cognitive complaints (CES-D M = 21.1, SD = 12.1) than HC without cognitive complaint (CES-D M = 8.5 SD = 7.1; t[50] = 3.28, p = .002).

Secondary Analysis

Within the BC group, we examined the role of time from completion of primary therapy on cognitive function controlling for age, education, and test administration format. Results indicated that survivors less than four years removed from primary therapy had significantly lower AVLT Delayed Recall scores than survivors four or more years removed from primary therapy (see Table 3). Cancer stage, exposure to radiation therapy, exposure to chemotherapy, and exposure to endocrine therapy were equally represented among patients less than 4 years and those 4 or more years from completion of primary therapy (all p’s > 0.20).

Table 3.

Test performance in BC sample as a function of time since therapy.

| Time from Completion of Primary Cancer Therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 4 years (n = 25) | 4 year and more (n = 24) | |||

| Mb | SD | Mb | SD | |

| AVLT Sum Recall (75)a | 47.8 | 6.6 | 49.3 | 8.0 |

| AVLT Delayed Recall (15) | 8.7 | 2.5 | 10.6* | 2.9 |

| Digit Span (30) | 17.4 | 3.2 | 18.0 | 4.8 |

| Symbol Digit (110) | 53.9 | 5.3 | 54.4 | 9.7 |

| COWA | 36.3 | 9.6 | 41.5 | 11.7 |

| Squire SRS (162) | 91.8 | 15.4 | 92.8 | 20.6 |

| CES-D (60) | 10.6 | 9.0 | 10.2 | 6.5 |

Note. AVLT = Auditory Verbal Learning Test; COWA = Controlled Oral Word Association; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; SRS = memory Self-report Scale.

Number in parenthesis is maximum possible score.

Means are adjusted for format of administration, age, and education. Three subjects were missing one or more co-variate values leading to total sample size of 49 in this analysis.

p < .05

Within the BC group, there was no significant relation between exposure to chemotherapy (coded as present or absent) controlling for age, education, and test administration format and cognitive test performance. A similar analysis examining the affects of exposure to endocrine therapy on cognitive performance was also non-significant.

DISCUSSION

As a group, breast cancer survivors in this study reported significantly more memory loss and exhibited significantly worse memory test performance than individually-matched healthy controls. At an individual level, 17% of the survivor group had clinically significant impairment in the efficiency of new learning as measured by Sum Recall on the AVLT, 17% were impaired on Delayed Recall, and 25% were impaired on one or both measures. About 12% of the survivors had significant executive function impairment (as measured by COWA). Across all five performance-based cognitive test indices, 15% of breast cancer survivors had impairment on two or more markers.

The rates of clinically significant breast cancer-associated cognitive impairment we report here are comparable to those from another control-group based study (Schagen et al., 2002). Our rates are a fair bit lower than those reported by Shilling and colleagues (which ranged up to 46% for methods most comparable to ours (Shilling et al., 2006). However, their breast cancer patients had just completed chemotherapy while all subjects in our study were at least one year removed from primary therapy with the average being approximately four years removed. If longer time from therapy is associated with lower rates of dysfunction, as is suggested by recent literature (see below), that may explain the pattern of findings between our two studies. Our rates of impairment are somewhat higher than those reported by Fan and colleagues for breast cancer patients 1 year from completion of therapy (Fan et al., 2005). That study used a screening instrument to document cognitive function. If the screener has limited sensitivity, then lower rates of impairment may result.

To put these findings in a larger clinical context, studies of patients with neurological disease using comparable methods tend to report rates of cognitive impairment that are higher. For example, almost one third of community-dwelling multiple sclerosis patients (Rao et al., 1991) and essentially all patients with Alzheimer disease (Welsh et al., 1991) exhibit clinically significant memory impairment on psychometric tests. While the frequency of memory impairment may be lower in breast cancer survivors, our data suggest that the problem is a clinically relevant one for a fair proportion of these patients (between 17-25%). In addition, the finding that 15% of the sample exhibited impairment on two or more cognitive tests across the full battery is significant, as less than 5% would be expected to do so by chance alone (Ingraham & Aiken, 1996).

The effect sizes we found for memory deficits in breast cancer survivors (0.45 - 0.53) were larger than in the Falleti meta-analysis of breast cancer patients (0.26) (Falleti et al., 2005) which may reflect the fact that the meta-analysis included studies that used less sensitive tests of memory (e.g. prose recall and recognition indices). Our effect sizes for attention (0.03 on Digit Span) and executive function (0.20 [average of COWA and Digit Symbol]) closely mirror the effect sizes reported by Faletti in those domains (0.03 and 0.18 respectively). The prominence of memory and executive deficits in cancer patients in general is reflected in the findings from another meta-analysis involving 14 controlled studies and over 700 subjects (with a wide array of cancer types, treatment regimens, and time since treatment) which showed that some of the largest effect sizes were in the memory and executive function domains (0.61 in each case) (Anderson-Hanley et al., 2003).

Our results are consistent with the idea that time from completion of primary cancer therapy may be an important variable in the assessment of cognitive function in breast cancer patients. In our study, participants who were less than four years removed from completion of therapy had significantly worse cognitive performance compared to those four or more years removed from treatment. These two groups did not differ in stage of disease at diagnosis and exposure to other treatments (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and endocrine therapy); however, our small sample size did not allow us to conduct a multivariable analysis controlling for all these factors simultaneously. Our results are consistent with other cross-sectional (Ahles et al., 2002) and longitudinal (Jenkins et al., 2006; Schagen et al., 2002; Fan et al., 2005) studies suggesting a time-dependent deleterious effect of cancer and/or cancer-related treatment on cognition.

Our results also indicated that exposure to chemotherapy or hormonal therapy did not appear to be related to current cognitive status in the breast cancer survivors. While our small sample size likely contributed to low power for this secondary analysis, the finding of no association between chemotherapy and cognitive status has been reported by others (Donovan et al., 2005; Jenkins et al., 2006). Several other studies have found relationships (van Dam et al., 1998; Brezden et al., 2000; Ahles et al., 2002; Tchen et al., 2003; Castellon et al., 2004b) although it may be time-limited (Schagen et al., 2002). Large studies with well matched patient subgroups that use multivariable analyses to account for variations in treatment approaches, age at diagnosis, and time from treatment will likely be required before these factors can be fully disentangled.

Consistent with much prior research involving older adults, we found that self-report of memory had little correspondence to actual measured memory performance and perhaps a closer linkage to depression (see (Reid & MacLullich, 2006) for review). A similar pattern has been reported specifically within breast cancer patients (Castellon et al., 2004a). Conversely, a recent study involving patients with clinically diagnosed mild cognitive disorder did show a significant correlation of self-estimates of memory and objectively measured memory independent of depression (Cook & Marsiske, 2006). Our small sample size may have limited our power to detect a relationship. It also likely that the relatively restricted range of memory dysfunction in our sample (milder impairments predominantly) attenuated the relationship between self-report and actual performance.

This study has limitations. Self-section bias is a significant limitation of this study. Our patient sample consisted of volunteers and therefore, may not be representative of the larger population of breast cancer survivors. However, the risk that our sample is extremely skewed seems unlikely since it is quite comparable, in age, cancer history, and extent of cognitive complaints, to a large observational study (n = 448) focused on late effects of primary cancer therapy in breast cancer survivors (Berglund et al., 1991). Another limitation of this study is the reliance on self-reported medical and treatment history (as opposed to medical record extraction) which can lead to inaccuracies and missing information that may obscure relationships between these factors and cognition. The battery of tests used in this study, while sensitive to a variety of causes of brain dysfunction (Zakzanis et al., 1999), was brief and lacked spatial processing and motor speed assessments. This could have contributed to an under-detection of dysfunction in this sample. Also, we did not collect information regarding the participants and healthy control’s menopausal or functional status. Future studies would benefit from including these assessments as it would help inform our understanding of potential contributing factors as well as support that the cognitive deficits identified are truly clinically relevant. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to make inferences regarding the cause of the cognitive dysfunction in our breast cancer survivors. A recent prospective longitudinal study suggests that a significant proportion of women with breast cancer had low cognitive function prior to treatment (Wefel et al., 2004). Further research is required to assess the impact of host, disease, and treatment factors in the cause and maintenance of cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer.

In conclusion, the breast cancer survivors in this study reported significantly more memory dysfunction and performed significantly worse than age- and education-matched healthy controls on tests of learning and memory. The psychometrically measured memory deficits reached levels of clinical impairment for 17-25% of the breast cancer survivor group. While the rate of clinically significant memory and cognitive impairment may be lower in breast cancer survivors than in other neurologic patient groups (e.g., multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer disease), the problem is important given the number of women affected and the relatively young age of the patients. Continued study of the role of disease and treatment variables in cognitive dysfunction associated with breast cancer is needed particularly as they use prospective, longitudinal designs and large sample sizes.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the American Cancer Society (RSGPB-04-089-01-PBP), the Mary Margaret Walther Program of the Walther Cancer Institute (100-200-20572), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG10133), and National Institute of Nursing Research training fellowship to Dr. Von Ah (T32 NR007066). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Anne Murphy-Knudsen and Ms. Sara Hickey.

Reference List

- Ahles TA, Saykin AJ. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007;7:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, Cole B, Mott LA, Skalla K, Whedon MB, Bivens S, Mitchell T, Greenberg ER, Silberfarb PM. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Hanley C, Sherman ML, Riggs R, Agocha VB, Compas BE. Neuropsychological effects of treatments for adults with cancer: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2003;9:967–982. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703970019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K. d. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. AJA Associates; Iowa City, Iowa: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund G, Bolund C, Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Sjoden PO. Late Effects of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Postoperative Radiotherapy on Quality-Of-Life Among Breast-Cancer Patients. European Journal of Cancer. 1991;27:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90295-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RJ, Bray F, Ferlay J, Parkin DM. Cancer incidence and mortality in the European Union: Cancer registry data and estimates of national incidence for 1990. European Journal of Cancer. 1997;33:1075–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezden C, Phillips K, Abdolell M, Bunston T, Tannock I. Cognitive function in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:2695–2701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.14.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capocaccia R, Verdecchia A, Micheli A, Sant M, Gatta G, Berrino F. Breast-Cancer Incidence and Prevalence Estimated from Survival and Mortality. Cancer Causes & Control. 1990;1:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00053180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellon SA, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Petersen L, Abraham L, Greendale GA. Neurocognitive performance in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy and tamoxifen. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004a;26:955–969. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellon SA, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Petersen L, Abraham L, Greendale GA. Neurocognitive performance in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy and tamoxifen. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004b;26:955–969. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KC, Tarone RE, Kessler LG, Ries LAG, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Edwards BK. Recent trends in US breast cancer incidence, survival, and mortality rates. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:1571–1579. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S, Marsiske M. Subjective memory beliefs and cognitive performance in normal and mildly impaired older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10:413–423. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Schmitt FA, Munster P, Jacobsen PB. Cognitive functioning after adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2499–2507. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falleti MG, Sanfilippo A, Maruff P, Weih LA, Phillips KA. The nature and severity of cognitive impairment associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: A meta-analysis of the current literature. Brain and Cognition. 2005;59:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan HGM, Houede-Tchen N, Yi QL, Chemerynsky I, Downie FP, Sabate K, Tannock IF. Fatigue, menopausal symptoms, and cognitive function in women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: 1-and 2-year follow-up of a prospective controlled study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:8025–8032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham LJ, Aiken CB. An empirical approach to determining criteria for abnormality in test batteries with multiple measures. Neuropsychology. 1996;10:120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Shilling V, Deutsch G, Bloomfield D, Morris R, Allan S, Bishop H, Hodson N, Mitra S, Sadler G, Shah E, Stein R, Whitehead S, Winstanley J. A 3-year prospective study of the effects of adjuvant treatments on cognition in women with early stage breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2006;94:828–834. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41:685–691. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid LM, MacLullich AMJ. Subjective memory complaints and cognitive impairment in older people. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2006;22:471–485. doi: 10.1159/000096295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. L’examen psychologique dans les cas d’encephalopathie traumatique. Archives de Psychologie. 1941;28:286–340. [Google Scholar]

- Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Mellenbergh GJ, van Dam FSAM. Change in cognitive function after chemotherapy: a prospective longitudinal study in breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:1742–1745. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Rosenbrand RM, van Rhijn D, Rodenhuis S, van Dam FSAM. Late effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognitive function: a follow-up study in breast cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13:1387–1397. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling V, Jenkins V, Trapala IS. The (mis)classification of chemo-fog - methodological inconsistencies in the investigation of cognitive impairment after chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2006;95:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zouzounis JA. Self-ratings of memory dysfunction: different findings in depression and amnesia. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology. 1988;10:727–738. doi: 10.1080/01688638808402810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Bielajew C, Collins B, Parkinson M, Tomiak E. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2006;20:76–89. doi: 10.1080/138540491005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchen N, Juffs HG, Downie FP, Yi QL, Hu H, Chemerynsky I, Clemons M, Crump M, Goss PE, Warr D, Tweedale ME, Tannock IF. Cognitive function, fatigue, and menopausal symptoms in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:4175–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverzagt FW, Monahan PO, Moser LR, Zhao Q, Carpenter JS, Sledge GW, Champion VL. The Indiana university telephone-based assessment of neuropsychological status: A new method for large scale neuropsychological assessment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:799–806. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707071020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam FSAM, Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, v.d.Wall E, Droogleever Fortuyn ME, Rodenhuis S. Impairment of cognitive function in women receiving adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose chemotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:210–218. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy J, Wefel JS, Ahles T, Tannock IF, Schagen SB. Cancer and cancer-therapy related cognitive dysfunction: An international perspective from the Venice cognitive workshop. Annals of Oncology. 2002;19:623–629. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-III Administration and Scoring Manual. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, Davis RN, Meyers CA. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2292–2299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh KA, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs RC, Heyman A. Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer’s disease using the CERAD neuropsychological measures. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48:278–281. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530150046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieneke MH, Dienst ER. Neuropsychological Assessment of Cognitive-Functioning Following Chemotherapy for Breast-Cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1995;4:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zakzanis K, Leach L, Kaplan E. Neuropsychological Differential Diagnosis. Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers; Lisse, Netherlands: 1999. [Google Scholar]