Health care reform evolves in distinct phases. Insurance reform, the critical first step, has been established with the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The nation now enters payment reform, a second chapter motivated by the need to slow health care spending. Payers across the country are increasingly putting health care on a budget, moving from fee-for-service to lump-sum payments for bundles of services or populations of patients.

Hospitals, health care centers, and physicians, in turn, are consolidating into Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) to address these new payment contracts, which reward lower spending and higher quality. In July, 89 new ACOs were launched in Medicare. Combined with 59 Medicare ACOs started in January, these organizations bring more than 130,000 physicians and 2.2 million beneficiaries into a new approach of organization-based health care.1 Global budget contracts from private insurers are doing the same for millions more working-age adults, their families, and their physicians.2

While insurance and payment reform have dominated policy attention, the third phase of health care reform—delivery system reform—has largely been ignored. Quietly underway in many parts of the country, this phase focuses attention on the culture of medicine. Its main actors are different. Where policymakers and economists led on insurance reform and payment reform, delivery system reform shines a spotlight on the modern physician organization, and asks these organizations to lead a cultural shift towards lower cost, higher value health care.

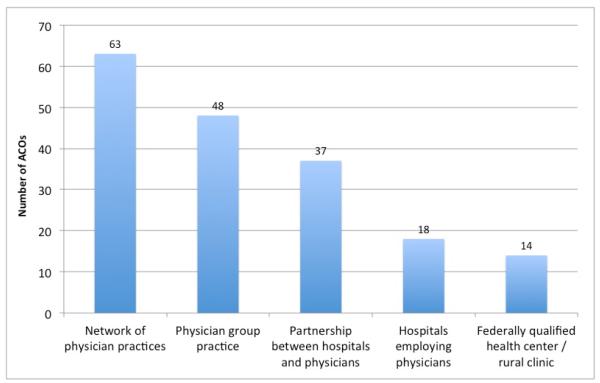

In today’s environment, the modern physician organization must be large enough to manage population health, nimble enough to cultivate teamwork across multiple specialties, and small enough to give each patient a home for his or her care. As physicians merge into ACOs, these organizations are assuming a variety of sizes and structures. Accountable care organizations in Medicare range from small group practices, to practices banded with hospitals, to integrated delivery systems consisting of academic medical centers and thousands of clinicians (Figure). From this starting point, little is known about how organizations can manufacture teamwork, about how they can overcome the historic silos of specialization to promote joint accountability, and about how they can turn a habit for volume into a passion for value.

Figure. Organizational Attributes of ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program*.

* Organizational attributes for the 89 Shared Savings Program (SSP) ACOs launched in July 2012 are collected as reported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; those for the 27 SSP ACOs launched in January 2012 are as gathered by the authors. Organizations with multiple attributes are counted multiple times. On average, SSP ACOs had about 1.5 attributes each.

Although some physician organizations were created with cultures that prepared them to be ACOs, such as Kaiser Permanente and Geisinger Health System, little is known about how to change the culture of organizations that began with a different DNA. Yet changing the culture of practice—beyond financial incentives and penalties and beyond merely putting clinicians under the same roof—is the best long-run hope for slowing spending from the ground up. Policy makers may help align incentives, but to truly shift medical practice, physicians must take the lead.

How does the modern physician organization embark on delivery system reform? The process begins with recognizing that “organizational knowledge,” which motivates the culture of practice, comes from organizational learning.3-4 In this era of delivery system reform, 3 domains are important building blocks for such learning.

First is leadership. The modern physician organization needs leaders who can motivate an organizational ethos that complements the professional ethos of medicine; not only is there a sacred patient-physician relationship, there is an equally important physician-physician relationship. In a global payment world, clinicians in an organization are truly in it together. When a physician chooses against an unnecessary test, savings accrue to the organization. When a case manager calls a patient and prevents an unnecessary visit to the emergency department, the organization benefits. When patients are satisfied with their care, the organization is rewarded. The modern physician organization must motivate its members to feel invested in one another. Organizations must value the clinician who counsels a patient about smoking as much as the one who removes the cancerous lung. This will require leadership that can unite clinicians in a shared vision as well as keep them together through difficult trade-offs. Shifting global payment dollars from inpatient care to primary care or from certain specialty services to others may be necessary, with potential implications for the composition of the physician workforce.

Second is incentives. The modern physician organization needs its clinicians to improve the collective value of their care, rather than advocate solely for their own portfolios of work. A focus on collective value orients the organization toward clinical benefit per dollar, encouraging reflections about how physicians work with one another, consult one another, and refer patients to one another, all of which affect resource utilization. Financial and nonfinancial incentives that reward value, particularly through teamwork, need to be carefully designed. Some organizations seem capable of delivering high-value care with physicians on salary. Other organizations have developed creative incentives to motivate physicians to care about their colleagues’ patients as well as their own.5 Still others have found new ways to measure and motivate team performance around common clinical scenarios, such as myocardial infarction and stroke.6 In designing incentives, the modern physician organization will likely benefit from an understanding of the behavioral economics of physician decision making and the emerging sociology of physician networks.7-8

Third is the patient’s role. The modern physician organization benefits not only when patients are satisfied with their physician, but also when patients are satisfied with the organization that integrates their care. The organization benefits not only when patients feel invested in their care, but also when the organization invests in its patients. To be sure, this reciprocity must be earned, but earning it is critical to reducing unnecessary spending. The economics of ACOs puts physicians and patients on the same team. As beneficial as reducing the supply of unnecessary care may be, reducing the demand for it is just as important. Adherence to medication regimens is key; judicious use of the emergency department even more so. For population health management to work, the population must feel empowered to manage its health. Indeed, the organization must motivate patients to actively partake in its mission, rather than simply be the means to its mission.

In an increasingly constrained health care environment, the imperative for medicine to look deep within itself is stronger than ever. Modern physician organizations must provide leadership for a health care system that needs a common vision. Undoubtedly, these organizations will compete—for patients, for physicians, and for resources. But through their size, influence, and training of new physicians, they are endowed with the opportunity to lead.

Physician organizations will need help, not just from patients, but also from payers at the bargaining table, drug companies at the checkout line, and a legal system that protects physicians when choosing against unnecessary care. But if these organizations can begin to shift the culture of medicine—if they can find ways to deliver better care at lower cost—they can begin to navigate health care through the era of delivery system reform.

Acknowledgements

Zirui Song acknowledges support from a National Institute on Aging Predoctoral M.D./Ph.D. National Research Service Award (F30 AG039175) and a Pre-doctoral Fellowship in Aging and Health Economics from the National Bureau of Economic Research (T32 AG000186).

Footnotes

Disclosures Dr Song is a medical student at Harvard Medical School. Dr Lee is network president of Partners HealthCare and chief executive officer for Partners Community HealthCare.

References

- 1.HHSannounces89newaccountablecareorganizations[newsrelease] [Accessed December 7, 2012];USDept of Health and Human Services. 2012 Jul 9; http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2012pres/07/20120709a.html.

- 2.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Safran DG. Building the path to accountable care. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2445–2447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohmer RMJ, Lee TH. Theshiftingmissionofhealthcaredeliveryorganizations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):551–553. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabow P, Halvorson G, Kaplan G. Marshalingleadershipforhigh-valuehealth care: an Institute of Medicine discussion paper. JAMA. 2012;308(3):239–240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee TH, Bothe A, Steele GD. How Geisinger structures its physicians’ compen- sation to support improvements in quality, efficiency, and volume. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(9):2068–2073. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TH. Care redesign: a path forward for providers. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):466–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1204386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groopman J. How Doctors Think. Houghton Mifflin; New York, NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landon BE, Keating NL, Barnett ML, et al. Variation in patient-sharing net- works of physicians across the United States. JAMA. 2012;308(3):265–273. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]