Summary

During infection, CD8+ T cells not only respond to antigenic signals through their T cell receptor (TCR), but also incorporate inflammatory signals from cytokines produced in the local infected microenvironment. Transient TCR-mediated stimulation will result in programmed proliferation that continues despite removal of the antigenic stimulus, but it remains unclear whether brief exposure to specific cytokines will elicit similar effects. Here, we have demonstrated that brief stimulation of memory T cells with interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 resulted in tightly regulated programmed proliferation in addition to acquisition of enhanced virus-specific cytokine production and cytolytic activity. CD8+ T cells briefly exposed to IL-12+IL-18 in vitro showed improved antiviral activity in vivo as demonstrated by increased proliferation and reduced viremia. These results indicate that even transitory exposure to inflammatory cytokines may provide a selective advantage to infiltrating CD8+ T cells by triggering a developmental program that is initiated prior to direct contact with virus-infected cells.

Introduction

T cell exposure to inflammatory cytokines is common during viral and microbial infections, but little is known about the short-term or long-term consequences that this may have on pre-existing memory T cells or their subsequent antiviral functions. Although the majority of T cells that respond to a given infection are antigen-specific (Butz and Bevan, 1998; Miller et al., 2008; Murali-Krishna et al., 1998), heterologous infection may nonetheless trigger a degree of bystander activation and proliferation of memory T cells (Ehl et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2002; Masopust et al., 2007). This may be due to a combination of inflammatory cytokine release (Kim et al., 2002; Tough et al., 1997) as well as potential stimulation by cross-reactive peptide epitopes (Brehm et al., 2002). Further studies have indicated that administration of inflammatory agents such as lipopolyssacharide (LPS) or poly I:C, will also induce limited CD8+ T cell proliferation in vivo (Kim et al., 2002; Tough et al., 1997), but it is unclear which cytokines are induced under these conditions or how long T cells are exposed to the inflammatory microenvironment. Although it was initially believed that continuous antigenic stimulation was required to maintain CD8+ T cell proliferation, several studies have demonstrated that T cells may undergo programmed proliferation in the absence of continued stimulation through the TCR (Kaech and Ahmed, 2001; Masopust et al., 2004; Mercado et al., 2000; van Stipdonk et al., 2003; van Stipdonk et al., 2001; Wong and Pamer, 2001, 2004). Bearing this in mind, a number of questions remain. For instance, can cytokines alone trigger programmed proliferation and differentiation of memory T cells following removal of the initial inflammatory signal? Could non-antigenic, cytokine-induced programmed proliferation of CD8+ T cells have a measurable impact on their antiviral functions?

In these studies, we examined several memory T cell characteristics including proliferative capacity, cytokine production, and cytolytic potential following a brief (5 hour) exposure to a defined inflammatory microenvironment containing the cytokines, IL-12 and IL-18. We found that virus-specific memory T cells did not require further antigenic stimulation in order to initiate programmed proliferation in response to IL-12+IL-18 and that during the course of programmed proliferation, these cells differentiated into strong effector T cells with enhanced antiviral functions. Moreover, brief exposure to IL-12+IL-18 provided a proliferative advantage during acute viral infection in vivo and resulted in reduced viremia. The IL-12+IL-18-induced programmed proliferation by CD8+ T cells was tightly regulated by CD4+ T cell help in the form of local paracrine IL-2 production and this may be a mechanism for limiting excessive bystander activation of T cells during heterologous infection. Based on these results, we propose a model in which memory CD8+ T cells begin to proliferate and differentiate into activated effector T cells upon encounter with an inflammatory microenvironment found at the periphery of a site of infection and that this enhances the host CD8+ T cell response by initiating a proliferative program and upregulating antiviral functions (e.g., enhanced cytokine production and cytolytic activity) prior to engagement with virus-infected target cells during migration into the infectious foci.

Results

Programmed proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells following exposure to IL-12+IL-18

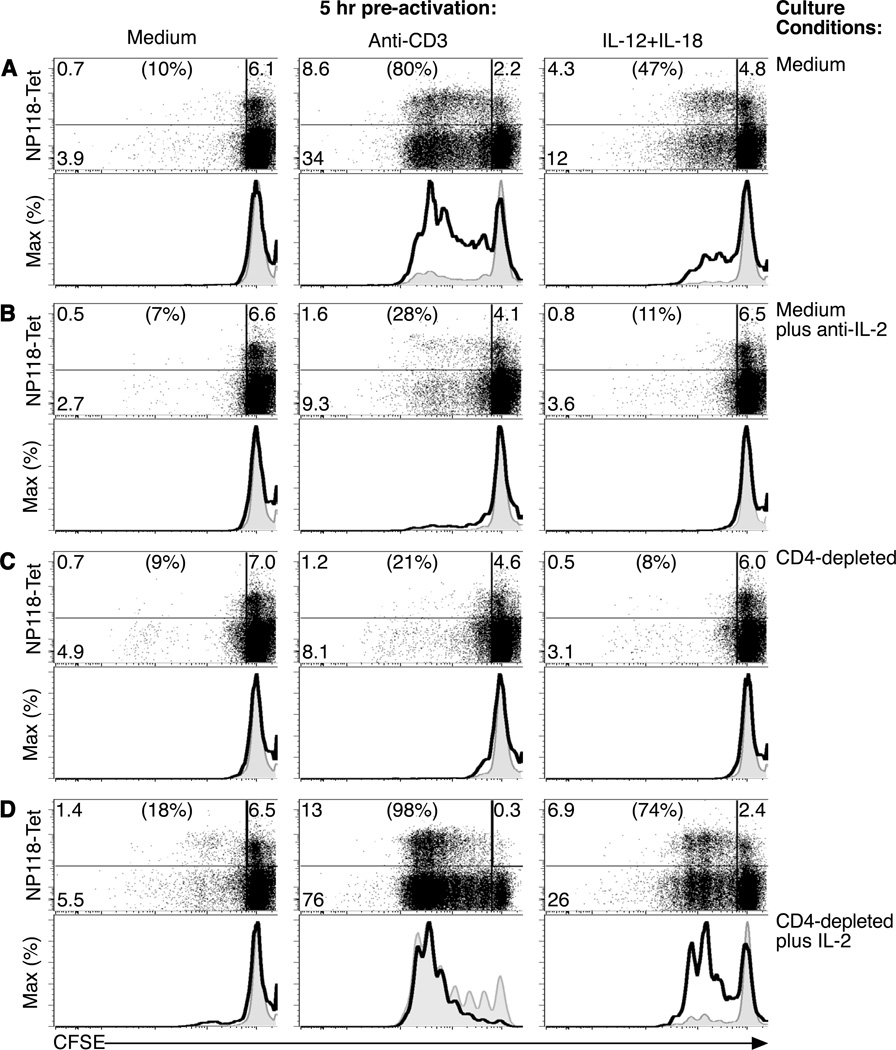

IL-12 and IL-18 are well-established activators of CD8+ T cells (Freeman et al., 2012) and exposure to this cytokine combination leads to the rapid activation of LCMV-specific T cells and production of IFNγ at concentrations that are comparable to that elicited by stimulation through the TCR [Supplemental Figure 1A, (Beadling and Slifka, 2005; Raue et al., 2004)]. This phenomenon is limited to CD8+ T cells with a CD11ahi phenotype since naïve T cells with a CD11alo phenotype are unresponsive to stimulation by this cytokine pair (Raue et al., 2004). In addition, exposure to IL-12+IL-18 or TCR stimulation by plate-bound anti-CD3 for as little as 5 hours induced upregulation of CD69 (Supplemental Figure 1B), an early marker of T cell activation and an inhibitor of T cell egress from sites of inflammation (Shiow et al., 2006) as well as upregulation of CD25 (Supplemental Figure 1C), another important activation marker that also comprises a subunit of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor. These observations indicate that both TCR stimulation and cytokine stimulation are effective at activating CD8+ T cells but little is known about the downstream outcome on proliferation, cytokine production, or cytolytic activity when measured in parallel. For these studies, spleen cells from mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) were stained with the vital dye, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE), which has been used extensively to examine the role of cell division in the differentiation of T cells (Bird et al., 1998; Goldrath et al., 2000; Murali-Krishna and Ahmed, 2000; Murali-Krishna et al., 1999). After 3 days of in vitro culture, LCMV NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cells that had been pre-cultured for 5 hours in medium alone failed to proliferate without exposure to either cytokines or antigenic stimulation through the TCR (Figure 1A). As expected, 5 hours of pre-activation with anti-CD3 was sufficient to trigger programmed proliferation by a subset of T cells after removal of the TCR-mediated stimulus. Similarly, we found that a subpopulation of LCMV NP118-specific CD8+ T cells that had been pre-activated with IL-12+IL-18 for just 5 hours would also reproducibly undergo 3–4 rounds of cell division in the absence of activation through the TCR (Figure 1A and data not shown). Residual IL-12 and IL-18 was not a factor since >99.999% of these cytokines were removed during the washing steps performed immediately after the initial 5 hour stimulation period (Beadling and Slifka, 2005). To determine the mechanisms underlying the observed programmed proliferation of T cells following either TCR-mediated or cytokine-mediated stimulation, we cultured the pre-activated T cells in medium containing a neutralizing antibody to IL-2 (10 µg/mL). Blocking IL-2 activity resulted in sharply reduced programmed proliferation (Figure 1B). Autocrine IL-2 production by briefly stimulated CD8+ T cells (Feau et al., 2011; Spierings et al., 2006) was an unlikely mechanism of action since we found that purified CD8+ T cells [obtained by magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS)] that were pre-activated with either anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18 failed to proliferate in vitro unless the cultures were supplemented with exogenous IL-2 (Supplemental Figure 1D). To determine if CD4+ T cells were the cellular source of IL-2, we specifically depleted CD4+ T cells by MACS (>90% depletion; data not shown) prior to the 3-day culture period (Figure 1C). Removal of CD4+ T cells resulted in dramatic inhibition of CD8+ T cell proliferation induced by brief exposure to anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18, thus indicating a need for CD4+ T cell help in this process. Culturing purified CD8+ T cells from LCMV-immune mice with naïve CD4+ T cells in a mixed splenocyte population was insufficient to rescue cytokine-induced programmed proliferation (Supplemental Figure 1E), further suggesting the importance of local cross-talk between memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations during the early stages of an inflammatory immune response. Although CD4+ T cells provide help to CD8+ T cells (Matloubian et al., 1994; Shedlock and Shen, 2003; Sun and Bevan, 2003; von Herrath et al., 1996) by a variety of means including CD40-CD40L interactions (Andreasen et al., 2000; Borrow et al., 1996; Whitmire et al., 1996) or by secretion of stimulatory cytokines such as IL-21 (Elsaesser et al., 2009; Gagnon et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2009), we found that specific depletion of IL-2 alone would block CD8+ T cell proliferation (Figure 1B), indicating that this cytokine is necessary for programmed proliferation to proceed. CD8+ T cells appeared to be highly sensitive to low concentrations of IL-2 since only a small fraction of CD4+ T cells from LCMV-immune mice spontaneously produced IL-2 directly ex vivo and this was not augmented by incubation with IL-12+IL-18 (Supplemental Figure 2A). To determine if IL-2 was sufficient for orchestrating programmed proliferation, CD4+ T cell-depleted cultures were supplemented with exogenous IL-2 during the 3-day culture period (1.5 ng/mL; Figure 1D). Although virus-specific memory T cells cultured in medium alone remained non-responsive to low-dose IL-2, programmed proliferation by anti-CD3-stimulated CD8+ T cells or IL-12+IL-18-stimulated CD8+ T cells was restored (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure 1D and 1E). Together, these results indicate that IL-2 is both necessary and sufficient for programmed proliferation of CD8+ T cells in vitro following stimulation through the TCR or following brief encounter with the inflammatory cytokines, IL-12+IL-18.

Figure 1. IL-12+IL-18 programs CD8+ T cells to proliferate in the absence of stimulation through the TCR.

Spleen cells from LCMV-immune mice (>100 days post-infection) were CFSE-labeled and cultured for 5 hours with medium, plate-bound anti-CD3, or IL-12+IL-18 (10 ng/mL, each). Cells were washed and then cultured for 3 days in (A) medium alone, (B) medium containing neutralizing anti-IL-2 antibody (10 µg/mL), (C) medium after depletion of CD4+ T cells, or (D) medium in which CD4+ T cells were depleted and cultures supplemented with exogenous IL-2 (1.5 ng/mL). Dotplots were gated on CD8+ T cells and the associated histograms were gated on NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cells (thick solid line) or NP118-tetramer− CD8+ T cells (thin line, gray fill). Proliferation is indicated by the step-wise loss of CFSE label. After 3 days of in vitro culture, NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cell recoveries were 3.9 × 104 (IL-12+IL-18), 3.2 × 104 (anti-CD3), and 3.1 × 104 (medium) per well. Data are representative of 6 experiments.

Cytokine-induced proliferating CD8+ T cells demonstrate enhanced peptide-specific cytokine production

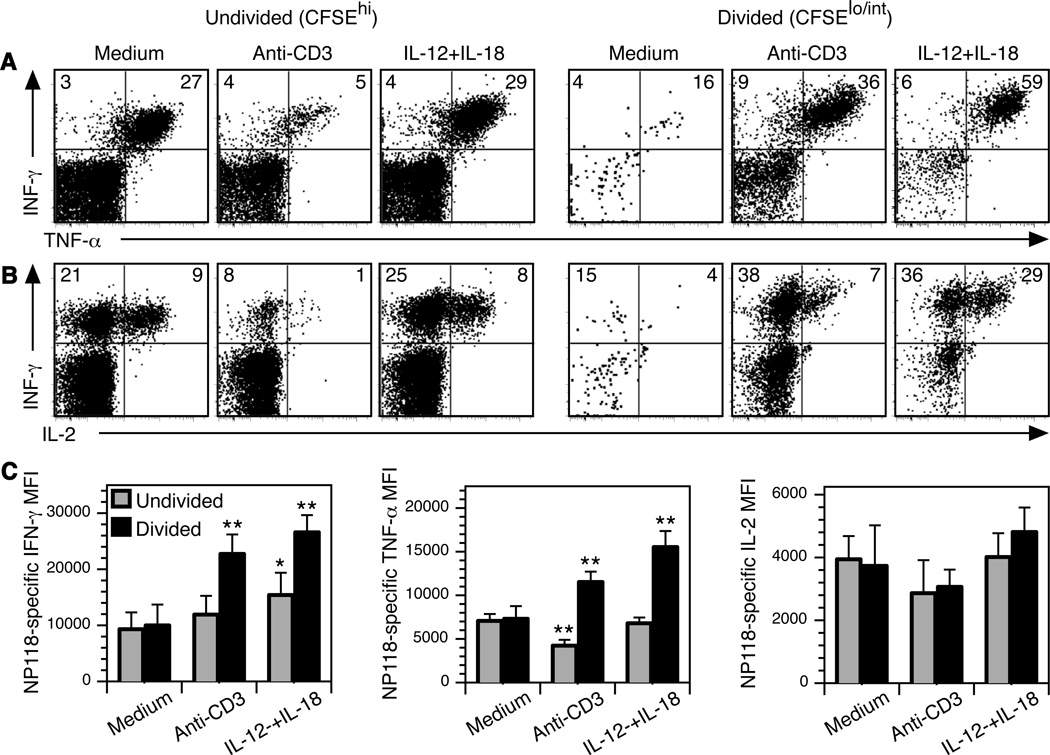

Previous studies have shown an association between proliferation and enhanced T cell effector function (Auphan-Anezin et al., 2003; Bajenoff et al., 2002; Bird et al., 1998; Murali-Krishna and Ahmed, 2000; Opferman et al., 1999). In the next series of experiments, we examined the link between proliferation and peptide-specific cytokine responses by memory T cells that had been briefly cultured in medium (negative control) or pre-stimulated for 5 hours with anti-CD3 or the combination of IL-12+IL-18 prior to 3 days of culture in unsupplemented medium (Figure 2). The majority of memory T cells that were cultured in medium alone remained CFSEhi, indicating that they had not proliferated during the 3-day culture period. As expected, their cytokine profile maintained a largely “memory” phenotype (Belz et al., 2001; Slifka and Whitton, 2000) with ~90% of the interferon-γ+ (IFN-γ+) CD8+ T cells also producing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) following 6 hours of stimulation with LCMV NP118-coated A20 cells (Figure 2). Parallel analysis using NP118-tetramer staining showed approximately a 1:1 ratio between NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells after peptide stimulation, indicating that there were no overtly dysfunctional T cells observed at 3 days after medium, anti-CD3, or IL-12+IL-18 treatment (data not shown). Antiviral CD8+ T cells that had been previously stimulated with anti-CD3 demonstrated normal or reduced TNF-α production following peptide stimulation with 57% of undivided CFSEhi IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells co-expressing TNF-α and 84% of T cells that had undergone one or more rounds of cell division (CFSElo/int) remaining capable of producing both cytokines after antigenic stimulation. Brief pre-exposure to IL-12+IL-18 at 3 days prior to viral peptide stimulation did not greatly alter the proportion of CD8+ T cells that expressed these cytokines since 87–90% of the IFN-γ+ NP118-specific CD8+ T cells maintained an IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ cytokine profile regardless of cell division.

Figure 2. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells pre-activated by IL-12+IL-18 respond better to subsequent peptide stimulation.

CFSE-labeled cells from LCMV-immune mice were cultured in medium, IL-12+IL-18, or plate-bound anti-CD3 for 5 hours, washed, and cultured in medium alone for 3 days. Next, cells were stimulated with NP118 peptide-coated A20 cells for 6 hours and IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 production was determined by intracellular cytokine staining analysis (ICCS). CD8+ T cells were gated on divided (CFSElo/int) or non-divided (CFSEhi) cell populations and the numbers in the quadrants indicate the percentage of CD8+ T cells producing (A) IFN-γ and TNF-α, or (B) IFN-γ and IL-2. In the absence of peptide stimulation, baseline TNF-α and IL-2 responses were ≤0.5% and IFN-γ was identified in 0.03–6% of CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 2). (C) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of cytokine expression was quantitatively determined and the amounts of cytokine production by divided (CFSElo/int) CD8+ T cells or undivided (CFSEhi) CD8+ T cells under each condition were compared to the cytokine expression by non-divided CFSEhi CD8+ T cells previously cultured in medium alone. A single asterisk (*) indicates P <0.02, two asterisks (**) indicate P <0.001. Data show the average and SD of 3 experiments.

We found that brief prior exposure to anti-CD3 stimulation resulted in a modest defect in IL-2 production following subsequent peptide stimulation (Figure 2B). Although 25–30% of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells cultured in medium alone were capable of producing IL-2 after peptide restimulation, T cells that had proliferated following brief TCR-mediated activation showed a reduction in IL-2 production, with <20% of virus-specific CD8+ T cells producing this important cytokine after exposure to cognate peptide. In contrast, antiviral CD8+ T cells that underwent programmed proliferation following transient exposure to IL-12+IL-18 demonstrated a substantially enhanced capacity for IL-2 production after peptide stimulation with approximately 40–60% of virus-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells capable of producing IL-2 (Figure 2B, and data not shown). This represented approximately a 3-fold improvement in peptide-specific IL-2 production when comparing CD8+ T cells undergoing TCR-mediated vs. cytokine-mediated programmed proliferation (P = 0.001).

Brief exposure to inflammatory cytokines (IL-12+IL-18) prior to antigenic stimulation with cognate peptide 3 days later not only resulted in a higher frequency of IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ IL-2+ T cells (Figure 2A, 2B, and data not shown), but these activated T cells also produced significantly more IFN-γ and TNF-α on a per-cell basis when compared to peptide-stimulated T cells previously cultured in medium alone (Figure 2C). This indicates that even several days after brief exposure to inflammatory cytokines, virus-specific CD8+ T cells remain poised to elicit strong antiviral cytokine responses following subsequent encounter with virus-infected (or in this case, peptide-coated) target cells.

Brief exposure to IL-12+IL-18 results in differentiation of memory T cells into cytolytic effectors

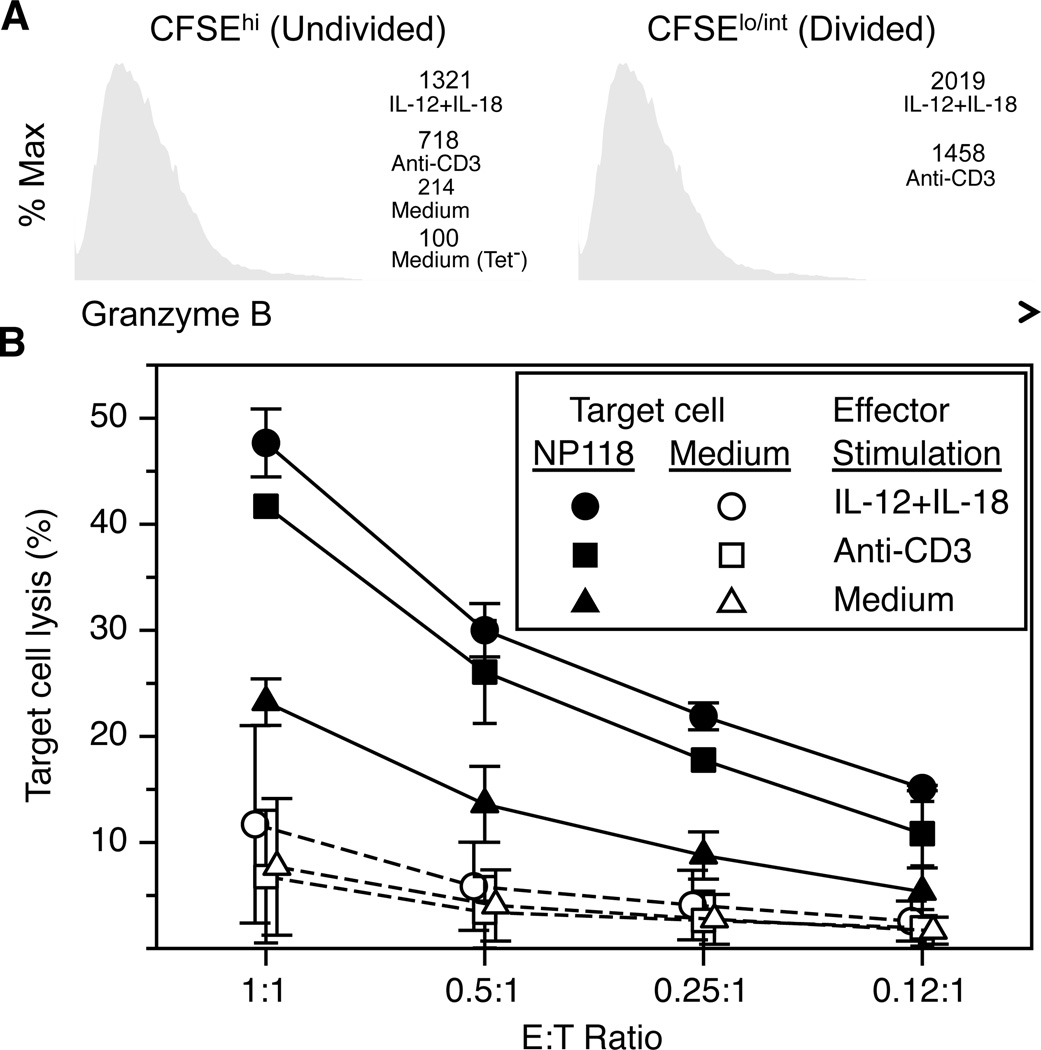

Acquisition of strong cytolytic activity is a key aspect of a successful CD8+ T cell-mediated immune response and brief exposure to IL-12+IL-18 for as little as 5 hours is sufficient to program virus-specific memory T cells to differentiate into highly cytolytic effector T cells (Figure 3). Unlike CD8+ T cells cultured in medium alone, prior exposure to either anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18 stimulation resulted in substantial upregulation of granzyme B expression by virus-specific NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cells (Figure 3A). As might be expected, NP118-specific CD8+ T cells that had proliferated (i.e., CFSElo/int) also expressed even higher amounts of granzyme B than T cells that had not undergone programmed proliferation. To determine if prior stimulation history would alter direct virus-specific cytolytic activity, MACS-purified CD8+ T cells were incubated with peptide-coated target cells at the indicated NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cell effector-to-target (E:T) ratios (Figure 3B). NP118-specific CD8+ T cells that had been cultured in medium alone showed only modest killing of peptide-coated target cells at the highest E:T ratios (<25% specific lysis). In contrast, memory CD8+ T cells that had been stimulated with anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18 at 3 days prior to performing the CTL assay demonstrated strong and equally efficient lysis of peptide-coated target cells. Collectively, this data shows that a brief encounter with inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12+IL-18 can induce changes in virus-specific CD8+ T cells that result in programmed proliferation of daughter cells that differentiate into more effective antiviral CD8+ T cells – even days after removal of the initial stimulus.

Figure 3. Memory T cells efficiently kill peptide-coated target cells after brief activation by IL-12+IL-18.

Splenocytes containing virus-specific CD8+ T cells from LCMV-immune mice (>120 days postinfection) were cultured in medium or stimulated with either plate-bound anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18 for 5 hours. The cells were then washed and incubated for 3 days without additional stimulation. (A) To assess granzyme B expression at 3 days after exposure to cytokines or anti-CD3 stimulation, T cells were segregated into undivided (CFSEhi) and divided (CFSElo/int) and stained for CD8, NP118-tetramer, and intracellular granzyme B. NP118-tetramer− CD8+ T cells cultured in medium alone (Tet−) served as a staining control. The numbers indicate the MFI of granzyme B in virus-specific T cells grown under the indicated conditions. (B) At 3 days after brief stimulation with IL-12+IL-18 or anti-CD3, CD8+ T cells were purified by MACS and small aliquots of T cells were enumerated by NP118-tetramer staining in order to adjust the peptide-specific effector:target (E:T) ratio to be the same in each sample during the CTL assay. Solid lines (closed symbols) indicate the % lysis of targets coated with NP118 peptide and dashed lines (open symbols) represent non-specific lysis of uncoated targets (A20 cells). Data show the average and SD of 2 experiments.

Prior exposure to IL-12+IL-18 improves T cell-mediated protection against subsequent viral infection

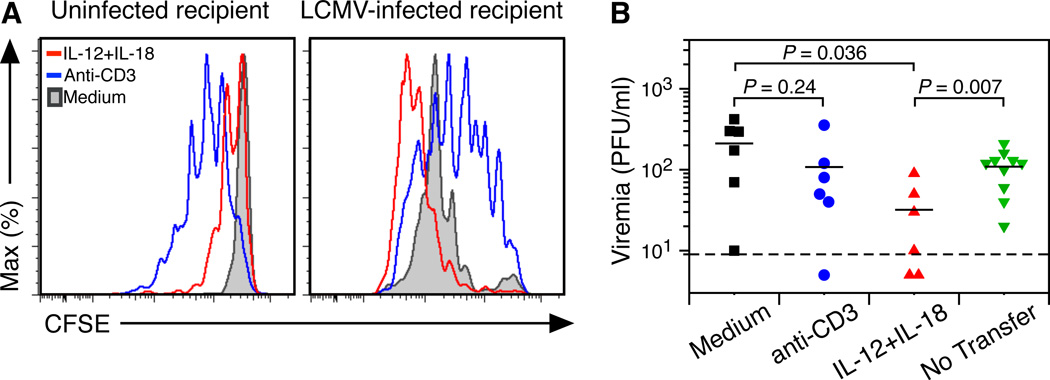

Programmed proliferation in vitro may differ from the results observed in vivo (Wong and Pamer, 2004). To determine if brief exposure to a defined combination of inflammatory cytokines will invoke a relevant change in T cell responses in vivo, CFSE-labeled splenocytes containing approximately 105 LCMV NP118-specific CD8+ T cells were cultured for 5 hours with medium, anti-CD3, or IL-12+IL-18 prior to washing steps to remove exogenous cytokines and were then adoptively transferred into congenic recipient mice (Figure 4). LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells previously cultured in medium alone showed no proliferation at 60 hours post-transfer into uninfected recipients (Figure 4A). Brief anti-CD3 stimulation triggered robust programmed proliferation of virus-specific T cells after transfer into uninfected animals despite no further stimulation through the TCR. In contrast, programmed proliferation by IL-12+IL-18 was aborted, with proliferation ceasing after only 1 round of proliferation. This suggests that inflammatory cytokine-induced programmed proliferation is tightly regulated and stops very quickly after T cells exit an inflammatory environment and are dispersed within uninfected tissues.

Figure 4. IL-12+IL-18 enhances virus-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation and results in decreased viremia.

LCMV-immune spleen cells from BALB/c Thy1.1 mice were CFSE-labeled, stimulated with anti-CD3 (blue), IL-12+IL-18 (red), or incubated in medium (gray) for 5 hours and washed prior to intravenous injection into BALB/c Thy1.2 mice. (A) Recipient animals were uninfected (left panel) or were infected with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV-Armstrong on the day of transfer (right panel). Proliferation of donor CD8+ T cells in the spleen was measured at 60–62 hours after adoptive transfer by staining for CFSE, CD8, Thy1.1, and NP118-tetramer. After transfer, the number of NP118-tetramer+ CD8+ T cells recovered per spleen in LCMV-infected recipients was 2.6 × 104 (IL-12+IL-18), 7.4 × 103 (anti-CD3), and 7.9 × 103 (medium). (B) Rapid acquisition of antiviral activity was measured by quantitating infectious LCMV in the serum (i.e., viremia) in comparison with mice that received no transferred cells. Data in (A) are representative of 3–4 mice per group from at least 3 experiments and data in (B) show the results of 5–6 mice per group obtained from 4 experiments except for the “no transfer” group which is based on 10 mice from 2 experiments.

Exposure to stimulatory cytokines (e.g., IL-2) has been shown to induce or enhance proliferation, but may also be involved in activation-induced cell death (AICD) (Waldmann, 2006) and may negatively impact T cell memory (Pipkin et al., 2010). To determine the long-term survival of LCMV-specific memory T cells that have been briefly activated by anti-CD3 or IL-12+IL-18, we transferred T cells to uninfected recipient mice and measured LCMV-specific donor CD8+ T cell numbers at 7, 28, and 70 days post-transfer (Supplemental Figure 3A). In the absence of further antigenic or cytokine-mediated stimulation, no substantial difference was observed in the survival rates of CD3-stimulated or IL-12+IL-18-stimulated CD8+ T cells in comparison with CD8+ T cells that had been pre-cultured in medium alone. To further test the potential effects of inflammatory cytokines on T cell memory, LCMV-immune mice were repeatedly injected with LPS [which triggers IL-12+IL-18 production by splenocytes in vitro; (Raue et al., 2004)] with no significant impact on NP118-specific CD8+ T cell memory observed (P = 0.38, Supplemental Figure 3B, 3C). Together, this indicates that brief exposure to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12+IL-18 induces proliferation and enhanced antiviral T cell activity without causing overt activation-induced cell death or loss of T cell memory.

To determine if T cell responsiveness to subsequent viral infection is altered by recent antigenic or inflammatory exposure history, parallel experiments were conducted in which an equal number of T cells (1 × 105 NP118-specific CD8+ T cells) were transferred into congenic mice that were infected with LCMV on the day of transfer (Figure 4A). Under these conditions, CD8+ T cells that had been cultured in medium alone proliferated rapidly during the first 60 hours after transfer into LCMV-infected mice. Likewise, CD8+ T cells previously stimulated by anti-CD3 also proliferated more in the infected microenvironment than they did after transfer into uninfected hosts. CD8+ T cells that had been stimulated by IL-12+IL-18 prior to transfer demonstrated the highest amount of proliferation in response to LCMV infection. Since high rates of proliferation may not necessarily indicate that higher protective efficacy is achieved, we also measured viremia following LCMV infection (Figure 4B). Following adoptive transfer and challenge with LCMV-Armstrong, CD8+ T cells previously stimulated with anti-CD3 performed similarly to the unstimulated medium-only controls, suggesting that 5 hours of pre-stimulation through the TCR may be insufficient for eliciting enhanced antiviral T cell function. In contrast, CD8+ T cells that had been exposed to IL-12+IL-18 for 5 hours prior to transfer reduced virus titers by 65–85% compared to naïve mice that received no T cells or naïve mice that received CD8+ T cells previously cultured in medium alone (P = 0.007 and P = 0.036, respectively). This indicates that the enhanced antiviral functions including increased cytokine production, cytolytic activity, and proliferation may have combined to provide a protective advantage against viral infection in vivo.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified programmed proliferation following transient exposure to inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-18 as a previously unrecognized feature of virus-specific T cell memory. Although naïve CD8+ T cells are largely refractory to stimulation by IL-12 and IL-18, it was expected that the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 would activate virus-specific CD8+ T cells (Berg et al., 2002; Berg et al., 2003; Kambayashi et al., 2003; Lertmemongkolchai et al., 2001; Raue et al., 2004; Tough et al., 2001). However, only brief encounter with these two inflammatory cytokines was sufficient to also induce a developmental program that resulted not only in continued proliferation, but also enhanced antiviral functions that were maintained for several days after removal of the initial stimulus. Programmed proliferation of CD8+ T cells appeared to be regulated by the availability of local CD4+ T cell help and we speculate that this may be an important factor in reducing unrestricted systemic proliferation as well as potential T cell-mediated immunopathology outside of the focal zone of an active infection.

Signaling through either the TCR or the IL-12 and IL-18 cytokine receptors will result in the activation of a group of transcription factors that partially, but not completely, overlap (Carroll et al., 2008; Smith-Garvin et al., 2009; Verdeil et al., 2006; Watford et al., 2004). TCR ligation and costimulation leads to phosphorylation of p56lck (Lck), Zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP70), and linker for activation of T cells (LAT), ultimately leading to activation of a variety of transcription factors including nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB), activator protein 1 (AP-1), and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). Binding of IL-12 to its receptor primarily results in activation of the Janus kinase (Jak) and Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) pathway via Jak2 and STAT4, as well as activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, particularly p38. The IL-18 receptor is a member of the IL-1 and Toll-like receptor family, and signals via immune receptor activated kinases (IRAKs) to activate NF-κB, AP-1, and other transcription factors. Because of the commonalities of TCR- and cytokine-induced transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB activation), stimulation of T cells with peptide or cytokines results in some shared outcomes (e.g., IFN-γ production, CD69 and CD25 upregulation) but not others. For instance, TNF-α and IL-2 are induced by peptide stimulation but not by IL-12+IL-18 stimulation (Beadling and Slifka, 2005). Differences between the precise combinations of signaling cascades and transcription factors that are activated by innate vs. antigenic signals are likely to contribute to the distinct cellular outcomes observed following exposure to these different stimuli.

Several inter-related factors appear to be involved with the regulation of cytokine-induced programmed proliferation and differentiation. First, exposure to IL-12 plus IL-18 initiates antiviral IFN-γ production by LCMV-specific CD8+ memory T cells within just 1–2 hours and IFN-γ expression peaks within 6–8 hours (Beadling and Slifka, 2005; Raue et al., 2004). This is assumed to act as an innate “sentinel response” to a local, yet unidentified microbial infection (Kambayashi et al., 2003; Lertmemongkolchai et al., 2001) prior to direct contact between the infiltrating T cells and infected target cells. Based on prior studies (Nguyen and Biron, 1999; Raue et al., 2004), it is likely that the concentrations of IL-12 and IL-18 used in this current study to activate CD8+ T cells in vitro is within the range of that which may occur in vivo during an inflammatory immune response. For instance, injection of LPS into LCMV-infected mice results in up to one third of CD8+ T cells becoming IFN-γ+ within 4 hours after administration (Nguyen and Biron, 1999) – even though LPS does not stimulate CD8+ T cells directly (Raue et al., 2004). Instead, LPS triggers the endogenous production of IL-12 and IL-18 (among other cytokines) that together elicit T cell activation and IFN-γ production. Indeed, exposing splenocytes from LCMV-infected mice to LPS will result in rapid production of IL-12 and IL-18 that subsequently triggers IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells within just 6 hours of in vitro culture (Raue et al., 2004). LPS does not trigger IFN-γ production in purified CD8+ T cells, indicating that de novo production of inflammatory cytokines by accessory splenic cells are required to mediate this effect. Depletion of LPS-induced IL-12 and IL-18 by the addition of neutralizing antibodies to these two specific cytokines resulted in >90% reduction in CD8+ T cell-mediated IFN-γ production, demonstrating that these two cytokines were responsible for the indirect LPS-induced T cell activation and IFN-γ expression by CD8+ T cells. Together with the data from in vivo administration of LPS (Nguyen and Biron, 1999), these studies show that local accessory cells in the spleen are capable of secreting enough IL-12 and IL-18 within 4–6 hours to elicit T cell activation and cytokine production similar to the results that we observed by direct supplementation of media with defined concentrations of these two cytokines.

In addition to rapidly producing IFN-γ, memory CD8+ T cells also upregulate CD69 and CD25 expression within 5 hours of exposure to IL-12+IL-18. Upregulation of CD69 inhibits T cell egress from the zone of inflammation, acting as important mechanism for maintaining the local T cell population on-site until the inflammatory insult has abated. Upregulation of CD25 also provides virus-specific memory T cells with the capacity to respond to proliferative signals generated by IL-2. Although the number of CD4+ T cells that spontaneously produce IL-2 in vitro was low, it is possible that IL-12+IL-18-induced upregulation of the high affinity receptor for IL-2, CD25, is key to enhanced sensitivity to local IL-2 production and could be an important mechanism for limiting CD8+ T cell proliferation to sites of acute infection. Regulatory T (Treg) cells are also believed to be major consumers of IL-2 and it is unknown if exposure to IL-12+IL-18 alters their regulatory functions or their IL-2 consumption in the context of an infected local microenvironment. Interestingly, although IL-12+IL-18 triggers strong IFN-γ responses, this interaction does not elicit detectable IL-2 production by CD8+ T cells (Beadling and Slifka, 2005) and this is a likely mechanism explaining why MACS-purified CD8+ T cells were unable to undergo programmed proliferation on their own. Likewise, purified anti-CD3-stimulated CD8+ T cells also failed to undergo programmed proliferation, but this may have been due to insufficient activation. Prior studies examining naïve CD8+ T cells have shown that insufficient TCR-mediated stimulation results in no further T cell expansion or only abortive clonal expansion (Mercado et al., 2000; van Stipdonk et al., 2003). We anticipated that 5 hours of anti-CD3 stimulation would have been sufficient for full activation of antigen-primed memory T cells, especially since this approach resulted in strong IFN-γ production, upregulation of CD69 and CD25 and programmed proliferation in vitro and in vivo. However, brief stimulation with anti-CD3 was not sufficient to improve rapid antiviral T cell responses in vivo and this may be due to a number of factors including the nature of the stimulus (e.g., plate-bound anti-CD3) or the short duration of stimulation. Another important question is how long cytokine-mediated enhancement of antiviral CD8+ T cell function will persist. For example, one would not expect permanent upregulation of CD69 and CD25 expression after brief exposure to an inflammatory microenvironment and it is probable that as T cells revert back to a resting memory state, their antiviral functions will also revert back to their baseline characteristics. Further studies will clearly be needed to understand the mechanisms underlying these observations and to determine how long enhanced protective antiviral activity is maintained.

During cytokine-induced programmed proliferation, activated CD25+ CD8+ T cells were primed to proliferate when given the appropriate signals, but this required costimulation in the form of IL-2 production by local CD4+ T cells. This 2-signal model of programmed proliferation may explain why increased cytolytic activity (Murali-Krishna et al., 1998) and limited bystander proliferation of non-antigen-specific CD8+ T cells occurs during heterologous infection (Masopust et al., 2007) or inflammation (Kim et al., 2002; Tough et al., 1997) without resulting in overt systemic proliferation of the greater memory T cell compartment. To determine the biological impact of cytokine-induced pre-conditioning on antiviral T cell responses in vivo, LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells were transferred to recipient mice that were infected with LCMV on the same day and proliferation was monitored by CFSE dilution. Cytokine-primed CD8+ T cells proliferated more rapidly in the context of LCMV infection than T cells previously primed by anti-CD3 stimulation or cultured in medium alone and demonstrated substantially improved reduction in viremia within just 60 hours after infection). These results, along with the observation of enhanced peptide-specific cytokine production and cytolytic activity in cytokine-primed CD8+ T cells provide the basis for our in vivo model. In this model, memory T cells responding to a local inflammatory event will undergo different stages of activation, differentiation and proliferation as they near a site of infection. By secreting IFN-γ at the perimeter of the infection, an innate barrier to viral replication and spread is initiated. As CD8+ and CD4+ T cells accumulate at the edge of an infectious foci, programmed proliferation is triggered and this results in an increase in local T cell number prior to entry into the site of infection and direct recognition of infected targets. Once the T cells enter the site of infection, the combined effects of cytokine-induced and TCR-driven activation and differentiation synergize to result in an enhanced antiviral immune response.

Together, the studies described here provide a previously unpublished example of how CD4+ T cell help may be important for enhancing antiviral CD8+ T cell function and provides further insight into the complex interactions that may occur during homologous or heterologous infection and how this might impact memory CD8+ T cell activation, proliferation, and subsequent antiviral function. Further studies will be needed to determine how long the cytokine-induced enhanced state of antiviral activity is retained by memory T cells following removal of the inflammatory stimulus. It is also unknown if this phenomenon is common to all memory T cell populations or if different subpopulations (e.g., effector-memory or central-memory) have different rates of responsiveness to inflammatory cytokine-induced programming. Likewise, it is unknown if programmed proliferation is unique to the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 or if other cytokines or cytokine combinations (Freeman et al., 2012) are able to elicit a similar enhancement of antiviral T cell function.

Experimental Procedures

Mice, LCMV infection, and adoptive transfer

BALB/cByJ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or bred at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU). BALB/c Thy1.1 mice were bred at OHSU. Mice were used at 6–12 wk of age. LCMV-immune mice were infected intraperitoneally with 2 × 105 PFU LCMV-Armstrong and T cell analysis was performed at 28–170 days post-infection. For adoptive transfer experiments, approximately 1 × 107 spleen cells containing 1 × 105 CFSE-labeled NP118-specific CD8+ Thy1.1+ T cells were transferred into Thy1.2+ mice with T cell responses and viremia (measured by LCMV plaque assay) performed at 60–62 hours post-transfer. All experimental procedures were approved by the OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents

HPLC-purified (>95% pure) LCMV NP118–126 (NP118) peptide (Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX) was used at 1 × 10−7M. IL-2 (human IL-2, Amgen Thousand Oaks, CA) was used at 1.5 ng/mL, IL-12 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) and IL-18 (Medical & Biological Laboratories, Watertown, MA) were used at 10 ng/mL. Anti-CD3ε (clone 145-2C11, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) was used to coat 24-well plates (20 µg/mL anti-CD3ε in PBS, 37°C for 1–2 hours and washed before use). Anti-IL-2 antibody (clone JES6-1A12, R&D Systems) was used at 10 µg/mL to neutralize IL-2 in culture. H-2Ld NP118-tetramer was obtained from the National Institutes of Health Tetramer Core Facility (Atlanta, GA). Anti-CD8a (clone 5H10) and anti-CD25 (clone PC61 5.3) were purchased from InVitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), anti-IL-2 (clone JES6-5H4), anti-TNFα (clone MP6-XT22), anti-CD69 (clone H1.2F3), anti-Granzyme B (clone CB11) and Propidium Iodine were obtained from BD Pharmingen. Anti-Thy1.1 (clone His51) was obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) and CFSE was purchased from InVitrogen.

CFSE proliferation and intracellular cytokine staining analysis

Single cell suspensions and in vitro stimulation conditions were performed as previously described (Beadling and Slifka, 2005). CD8+ T cell isolation and CD4+ T cell depletion were performed by MACS using anti-CD8α or anti-CD4 microbeads and protocols supplied by Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Post-MACS analysis indicated >90% purity. Cells were labeled with 5 µM CFSE for in vivo experiments and with 1 µM CFSE for in vitro experiments. CFSE-labeled T cells were stimulated in anti-CD3ε coated plates, IL-12 + IL-18 (both 10 ng/ml) or medium alone at 37°C/6% CO2 for 5 hours. Cells were washed extensively and cultured in RPMI 10% FBS supplemented with 50 mM 2-MercaptoEthanol in 24 well plates for 3 days (64–68 hours) to assess proliferation. Antiviral cytokine production was measured by ICCS at 6 hours after adding a 1:1 ratio of A20 cells (a B cell line) coated with 10−7 M NP118–126 peptide. All flow cytometry data was analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Non-radioactive flow cytometry-based CTL assay

A20 target cells were labeled with 4 µM (CFSEhi) or 1.5 µM (CFSElo) CFSE. CFSElo cells were coated with peptide (10−7 M NP118). Target cells were washed twice and resuspended in RPMI 10% FBS. CFSEhi and CFSElo A20 cells were combined 1:1 at 1 × 104 cells/ml (target cell suspension). For the CTL assay 100 µl target cell suspension was combined with 100 µl effector cell (NP118-specific CD8+ T cells) suspensions at different effector-to-target ratios in round-bottom 96 well plates and incubated at 37°C/6% CO2 for 5 hours. To assess CTL activity, cells were washed with PBS and stained with 0.25% Propidium Iodine in PBS at 4°C for 15 minutes. Samples were acquired immediately on a FACSCalibur (BD, San Jose, CA) and % viability determined by Propidium Iodine staining in comparison with positive and negative controls.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student’s t-test with unequal variance was used to evaluate statistical significance of differences between groups. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ian Amanna for assistance with in vivo experiments and Bailey Freeman for helpful scientific discussions. This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health grants, UO1 AI082196 U54 (to M.K.S.), RO1 AI054458 (to M.K.S.), and ONPRC grant 8P51OD011092-53 (to M.K.S.). H-2Ld NP118-tetramers were prepared by the National Institute of Health Tetramer Core Facility (Atlanta, GA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andreasen SO, Christensen JE, Marker O, Thomsen AR. Role of CD40 ligand and CD28 in induction and maintenance of antiviral CD8+ effector T cell responses. J Immunol. 2000;164:3689–3697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auphan-Anezin N, Verdeil G, Schmitt-Verhulst AM. Distinct thresholds for CD8 T cell activation lead to functional heterogeneity: CD8 T cell priming can occur independently of cell division. J Immunol. 2003;170:2442–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajenoff M, Wurtz O, Guerder S. Repeated Antigen Exposure Is Necessary for the Differentiation, But Not the Initial Proliferation, of Naive CD4(+) T Cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:1723–1729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadling C, Slifka MK. Differential regulation of virus-specific T-cell effector functions following activation by peptide or innate cytokines. Blood. 2005;105:1179–1186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belz GT, Xie W, Doherty PC. Diversity of epitope and cytokine profiles for primary and secondary influenza a virus-specific cd8(+) t cell responses. J Immunol. 2001;166:4627–4633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RE, Cordes CJ, Forman J. Contribution of CD8+ T cells to innate immunity: IFN-gamma secretion induced by IL-12 and IL-18. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2807–2816. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2807::AID-IMMU2807>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird JJ, Brown DR, Mullen AC, Moskowitz NH, Mahowald MA, Sider JR, Gajewski TF, Wang CR, Reiner SL. Helper T cell differentiation is controlled by the cell cycle. Immunity. 1998;9:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P, Tishon A, Lee S, Xu J, Grewal IS, Oldstone MB, Flavell RA. CD40L-deficient mice show deficits in antiviral immunity and have an impaired memory CD8+ CTL response. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2129–2142. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm MA, Pinto AK, Daniels KA, Schneck JP, Welsh RM, Selin LK. T cell immunodominance and maintenance of memory regulated by unexpectedly cross-reactive pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:627–634. doi: 10.1038/ni806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz EA, Bevan MJ. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll HP, Paunovic V, Gadina M. Signalling, inflammation and arthritis: Crossed signals: the role of interleukin-15 and -18 in autoimmunity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1269–1277. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehl S, Hombach J, Aichele P, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Bystander activation of cytotoxic T cells: studies on the mechanism and evaluation of in vivo significance in a transgenic mouse model. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1241–1251. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.1174182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feau S, Arens R, Togher S, Schoenberger SP. Autocrine IL-2 is required for secondary population expansion of CD8(+) memory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:908–913. doi: 10.1038/ni.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman BE, Hammarlund E, Raue HP, Slifka MK. Regulation of innate CD8+ T-cell activation mediated by cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9971–9976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203543109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon J, Ramanathan S, Leblanc C, Cloutier A, McDonald PP, Ilangumaran S. IL-6, in synergy with IL-7 or IL-15, stimulates TCR-independent proliferation and functional differentiation of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:7958–7968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrath AW, Bogatzki LY, Bevan MJ. Naive T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:557–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Ahmed R. Memory CD8+ T cell differentiation: initial antigen encounter triggers a developmental program in naive cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:415–422. doi: 10.1038/87720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambayashi T, Assarsson E, Lukacher AE, Ljunggren HG, Jensen PE. Memory CD8(+) T Cells Provide an Early Source of IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2003;170:2399–2408. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Brehm MA, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Dynamics of memory T cell proliferation under conditions of heterologous immunity and bystander stimulation. J Immunol. 2002;169:90–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lertmemongkolchai G, Cai G, Hunter CA, Bancroft GJ. Bystander Activation of CD8(+) T Cells Contributes to the Rapid Production of IFN-gamma in Response to Bacterial Pathogens. J Immunol. 2001;166:1097–1105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masopust D, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. The role of programming in memory T-cell development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masopust D, Murali-Krishna K, Ahmed R. Quantitating the magnitude of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific CD8 T-cell response: it is even bigger than we thought. J Virol. 2007;81:2002–2011. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01459-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M, Concepcion RJ, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. Journal of Virology. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado R, Vijh S, Allen SE, Kerksiek K, Pilip IM, Pamer EG. Early programming of T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:6833–6839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, van der Most RG, Akondy RS, Glidewell JT, Albott S, Masopust D, Murali-Krishna K, Mahar PL, Edupuganti S, Lalor S, et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity. 2008;28:710–722. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali-Krishna K, Ahmed R. Naive T Cells Masquerading as Memory Cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:1733–1737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, Sourdive DJD, Zajac AJ, Miller JD, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: A reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali-Krishna K, Lau LL, Sambhara S, Lemonnier F, Altman J, Ahmed R. Persistence of memory CD8 T cells in MHC class I-deficient mice. Science. 1999;286:1377–1381. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen KB, Biron CA. Synergism for cytokine-mediated disease during concurrent endotoxin and viral challenges: Roles for NK and T cell IFN-γ production. J Immunol. 1999;162:5238–5246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opferman JT, Ober BT, Ashton-Rickardt PG. Linear differentiation of cytotoxic effectors into memory T lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:1745–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pipkin ME, Sacks JA, Cruz-Guilloty F, Lichtenheld MG, Bevan MJ, Rao A. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity. 2010;32:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raue HP, Brien JD, Hammarlund E, Slifka MK. Activation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12 and IL-18. J Immunol. 2004;173:6873–6881. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300:337–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdickova N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, Cyster JG, Matloubian M. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Activated and memory CD8+ T cells can be distinguished by their cytokine profiles and phenotypic markers. J Immunol. 2000;164:208–216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spierings DC, Lemmens EE, Grewal K, Schoenberger SP, Green DR. Duration of CTL activation regulates IL-2 production required for autonomous clonal expansion. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1707–1717. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JC, Bevan MJ. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science. 2003;300:339–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1083317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tough DF, Sun S, Sprent J. T cell stimulation in vivo by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) J Exp Med. 1997;185:2089–2094. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tough DF, Zhang X, Sprent J. An IFN-gamma-dependent pathway controls stimulation of memory phenotype CD8(+) t cell turnover in vivo by IL-12, IL-18, and IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 2001;166:6007–6011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stipdonk MJ, Hardenberg G, Bijker MS, Lemmens EE, Droin NM, Green DR, Schoenberger SP. Dynamic programming of CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:361–365. doi: 10.1038/ni912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stipdonk MJ, Lemmens EE, Schoenberger SP. Naive CTLs require a single brief period of antigenic stimulation for clonal expansion and differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:423–429. doi: 10.1038/87730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdeil G, Chaix J, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Auphan-Anezin N. Temporal cross-talk between TCR and STAT signals for CD8 T cell effector differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:3090–3100. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Herrath MG, Yokoyama M, Dockter J, Oldstone MBA, Whitton JL. CD4-deficient mice have reduced levels of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes after immunization and show diminished resistance to subsequent virus challenge. J. Virol. 1996;70:1072–1079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1072-1079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watford WT, Hissong BD, Bream JH, Kanno Y, Muul L, O'Shea JJ. Signaling by IL-12 and IL-23 and the immunoregulatory roles of STAT4. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:139–156. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire JK, Slifka MK, Grewal IS, Flavell RA, Ahmed R. CD40 ligand-deficient mice generate a normal primary cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response but a defective humoral response to a viral infection. J Virol. 1996;70:8375–8381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8375-8381.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Pamer EG. Cutting edge: antigen-independent cd8 t cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2001;166:5864–5868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Pamer EG. Disparate in vitro and in vivo requirements for IL-2 during antigen-independent CD8 T cell expansion. J Immunol. 2004;172:2171–2176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1572–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1175194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.