Abstract

In eukaryotes, a variant of conventional histone H3 termed CenH3 epigenetically marks the centromere. The conserved CenH3 chaperone specifically recognizes CenH3 and is required for CenH3 deposition at the centromere. Recently, the structures of the chaperone/CenH3/H4 complexes have been determined for H. sapiens (Hs) and the budding yeasts S. cerevisiae (Sc) and K. lactis (Kl). Surprisingly, the three structures are very different, leading to different proposed structural bases for chaperone function. The question of which structural region of CenH3 provides the specificity determinant for the chaperone recognition is not fully answered. Here, we investigated these issues using solution NMR and site-directed mutagenesis. We discovered that, in contrast to previous findings, the structures of the Kl and Sc chaperone/CenH3/H4 complexes are actually very similar. This new finding reveals that both budding yeast and human chaperones use a similar structural region to block DNA from binding to the histones. Our mutational analyses further indicate that the N-terminal region of the CenH3 α2 helix is sufficient for specific recognition by the chaperone for both budding yeast and human. Thus, our studies have identified conserved structural bases of how the chaperones recognize CenH3 and perform the chaperone function.

During mitosis, paired sister chromatids are segregated equally into daughter cells by microtubules that are attached to the mitotic spindle at the centromere through a multi-protein complex called the kinetochore (1). A conserved conventional H3 variant termed CenH3 (Cse4 in budding yeast and CENP-A in human) epigenetically marks the centromere and supports the formation of the kinetochore complex (2). CenH3-specific chaperones (Scm3 in budding yeast and HJURP in human) are required for the deposition of CenH3 at centromeres (3–10). The structures of three of the chaperones in complex with the corresponding CenH3/H4 histones of S. cerevisiae (Sc) (11), K. lactis (Kl) (12), and H. sapiens (Hs) (13) have been determined at atomic resolution (Fig. 1A–C). In each of the structures, the chaperone forms a heterotrimer with CenH3/H4 and binds to the histone sites that interact with DNA in the canonical nucleosome structure (Fig. 1A–C), providing a structural mechanism for its chaperone function, whereby binding between the chaperone and histones prevents the direct interaction between histones and DNA.

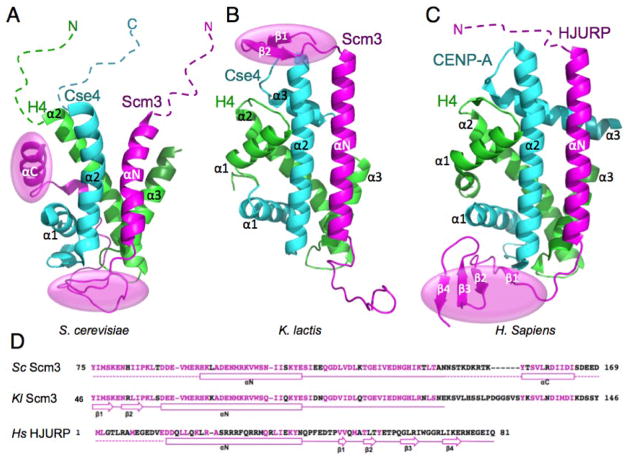

Figure 1.

Comparison of the three structures of CenH3/H4 histones in complex with the homologous domains of their chaperones (15).(A) Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4. (B) Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4. (C) Hs HJURP/CENP-A/H4. The dashed lines indicate unfolded regions. The transparent ovals (magenta) indicate the regions that block DNA binding to the histones. In (A)–(C), the chaperone, CenH3, and H4 are in magenta, cyan and green, respectively. (D) The amino acid sequences of the CenH3/H4 binding domains of the chaperones. Solid lines show folded regions and secondary structures in the chaperone/CenH3/H4 complexes, whereas the dashed lines represent unstructured regions. Conserved residues between Sc and Kl Scm3 are shown in magenta while non-conserved residues are shown in black. For Hs HJURP, conserved residues between HJURP and Scm3 are shown in magenta while non-conserved residues are shown in black.

Despite the common structural features of the chaperone-histone heterotrimers, surprisingly large differences are apparent in the three structures (Fig. 1A–C). For example, a large portion of the Cse4/H4 structure in the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex is unstructured, whereas the CenH3/H4 histones in the Kl and Hs complexes have a completely ordered histone-fold. Also, the N-terminal region of the Kl Scm3 forms a β-hairpin and occupies the DNA binding sites of the nucleosome histones, while in contrast, the corresponding regions in the Sc Scm3 and Hs HJURP are unfolded. The structural differences between the Sc and Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complexes are particularly striking, especially because the corresponding histones and chaperones have a very high sequence homology (Fig. 1D and (12)). These differences lead to different conclusions regarding the structural basis of the chaperone functions, namely that the Sc Scm3 uses the C-terminal helix and the loop region that follows the N-terminal helix to prevent binding of DNA to the L1 loop of Cse4 and the L2 loop of H4, while the N-terminal β-hairpin of the Kl Scm3 prevents binding of DNA to the L2 loop of Cse4. There has been much speculation about the possible causes for the structural differences of the Sc and Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complexes. Cho and Harrison suggested that the deletion of the α1 helix of H4 and the use of a single-chain model may have led to an incorrect NMR structure of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (12). On the other hand, Zhou et al. pointed out that the shorter Scm3 construct used to determine the structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex, together with crystal packing, may have conduced to form the completely folded histone-fold structure (14, 15).

In addition, it is currently debated which structural region in CenH3 is the determinant for specific recognition by the chaperone. We have previously shown that four Sc Cse4-specific residues in the N-terminal region of the α2 helix are necessary and sufficient for Scm3 recognition (11). In contrast, it was proposed that a single CENP-A-specific residue in the α1 helix, which is located outside of the centromere-targeting domain of CENP-A (CATD, loop 1 and helix 2), is the primary specificity determinant (13, 16).More recently, it was suggested that the combination of the two C-terminal residues in the α2 helix of CENP-A with either one of the two residues in the N-terminal portion of the α2 helix or the L1 loop is sufficient for CENP-A recognition by HJURP(17).

Here, we have investigated both issues using solution NMR and site-directed mutagenesis methods. We find that the solution structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex is similar to that of the Sc complex, and the functionally important structural regions in the chaperone/CenH3/H4 complex are largely conserved.

Results

Solution conformation of the chaperone/CenH3/H4 complex

To determine whether the shorter Scm3 construct and crystal packing could affect the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 structure, we examined this complex at pH 5.6 (physiological condition for budding yeast). We used a longer Kl Scm3 that includes the additional C-terminal region corresponding to the unfolded loop and the αC helix in the NMR structure of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (Fig. 1D) (11). This Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (Tables S1 and S2) has a molecular weight larger than 30 kDa and precipitates at temperatures higher than 30°C, prohibiting a full structural determination by NMR. Therefore, we focused on the identification of the unfolded regions of the complex for which NMR signals are readily observable at room temperature due to fast local dynamic motions. Indeed, we observed a large number of cross peaks in the 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra (Fig. 2A, B), indicating that many residues have anunfolded conformation. We then used 15N/13C-labeled Kl Scm3 chaperone and unlabeled Cse4/H4 histones, and vice versa, to assign the backbone chemical shifts of the observable cross peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra (18). The difference between the measured values and those of random coils for the Cα chemical shifts are between -1 and +1 for most of the residues (Fig. 2C–E). No consecutive three residues have values larger than +1 or smaller than -1, indicating that the observed residues are indeed unfolded (19, 20).

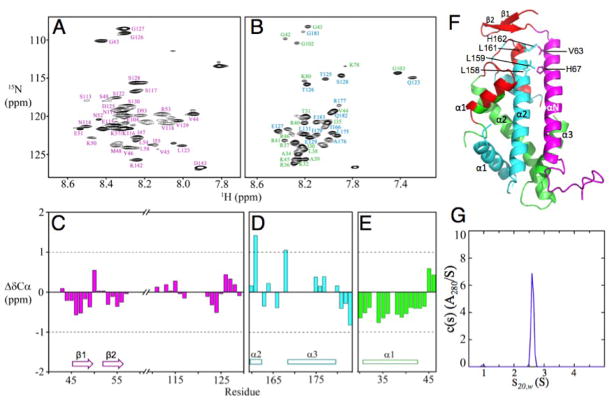

Figure 2.

Unstructured regions in the three-chainKl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex at pH 5.6.(A) 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of Scm3 in the complex. (B) 1H-15N TROSY spectra of Cse4 and H4 in the complex. Assignments are in cyan color for Cse4 and in green for H4. (C) Cα chemical shift deviations from random coil values for Scm3. (D) and (E) Cα chemical shift deviations from random coil values for Cse4 and H4, respectively. The corresponding secondary structural regions in the crystal structure are shown. (F) Mapping of the unfolded regions (red color) of the Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex at pH 5.6 onto the crystal structure. (G) Analytical ultracentrifugation analysis of the Scm3/Cse4(L158G/L159G/L161G/H162G)/H4 complex at pH 5.6 and a loading concentration of at 35 μM. A single species at 2.61 S is observed, having an estimated molecular weight of 33.0 kDa consistent with a heterotrimeric complex.

The unfolded residues are in the regions of 43–57 and 111–129 of Kl Scm3, 160–183 of Kl Cse4, and 30–46 of Kl H4 (Fig. 2F), which either form folded structures or are absent in the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (12). For example, Kl Scm3 residues 44–57 form the N-terminal β-hairpin while Scm3 residues 116–129 are absent (Fig. 1B); Cse4residues 160–183 form the last turn of the α2 helix, the L2 loop and the α3 helix; H4 residues 31–42 form the α1 helix. In contrast, these regions correspond to those that are unfolded in the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 NMR structure (11, 14). Kl Scm3 regions 59–103 and 131–139, Cse4 regions 110–122 and 132–159, and H4 regions 48–77 and 81–98 are not observable by NMR, suggesting that they have folded structures. In the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex, Kl Scm3residues 59–91 form the αN helix, while Kl Scm3residues 92–103 form an irregular structure and have no interactions with the histone proteins. The Kl Scm3 residues 131–139 are absent in the crystal structure whereas the corresponding residues in Sc Scm3 form the αC helix in the NMR structure of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex. The αN helix of the Kl Scm3 appears to be longer than that of Sc Scm3 by two helical turns at the N-terminal region. We found at lower temperature (25°C) that the corresponding region in Sc Scm3 also folds to an α-helical conformation in the complex (Fig. S1) (the NMR structure of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex was determined at 35°C), indicating that temperature plays a role in the formation of its structure. In addition, mutation of four residues (L158, L159, L161, and H162) in the C-terminal region of the α2 helix of Kl Cse4 in the crystal structure to Gly did not prevent the formation of a heterotrimeric complex with the Kl Scm3 and H4 (Fig. 2F, G), indicating that this region is not essential for recognition by Kl Scm3. Thus, our results reveal that the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex has similar unfolded regions as the solution structure of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (Fig. 1A).

We also used NMR to examine the human HJURP/CENP-A/H4 complex at both pH 5.6 and pH 7.0. We found that the α1 helix of H4 becomes unstructured at pH 5.6, whereas CENP-A remains fully folded except for the C-terminal last three residues (Fig. S2). However, at pH 7.0, only HJURP residues 2–10 and 76–81 and H4 residues 22–30 are unstructured (Fig. S2), consistent with the crystal structure (13).

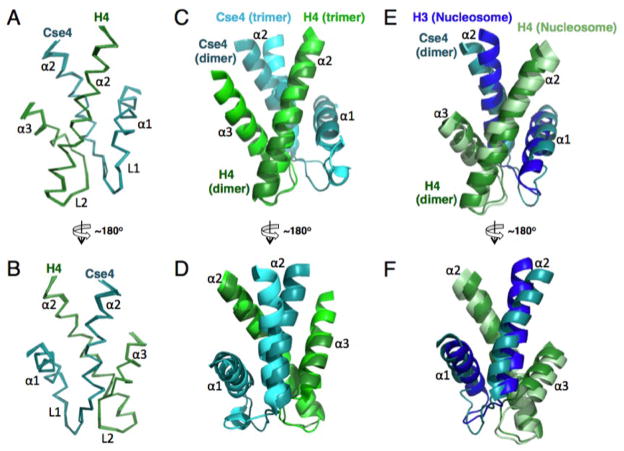

Structural determination of the partially unfolded Cse4/H4 dimer

In our previous structural determination of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex, we showed that the free Sc Cse4/H4 dimer is partially unfolded(11). The unfolded regions include the residues corresponding to those in the C-terminal region of the α2 helix, the L2 loop, and the α3 helix of Cse4 and the α1 helix of H4 within the histone fold. Here, we also examined the Kl Cse4/H4 complex and found that it is as partially unfolded as the Sc Cse4/H4 complex (Fig. S3). In order to determine whether the folded region of the Sc Cse4/H4 dimer has a structure similar to that in the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex, we determined its structure at pH 5.6 and 35°C using a single-chain model (Fig. 3, Fig. S4 and Table S3). In this model, the C-terminal region of the α2 helix of Cse4 is linked to the N-terminal region of the α2 helix of H4 through a six-residue linker that includes a thrombin protease-cutting site (Table S2). The folded regions of the histones have RMSDs of 0.2 Å for the backbone and 0.8 Å for full atoms. A comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the unlinked Sc Cse4/H4 dimer (produced by thrombin cleavage) and that of the single-chain model shows that the linker has little effect on the chemical shifts of the folded regions (Fig. S4), indicating that the structure of the folded region in the Sc Cse4/H4 dimer is not altered in the single chain model. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that the distance between the N-terminus of the α2 helix of H4 and the C-terminus of the α2 helix of Cse4 in this dimer is longer than that of the corresponding H4 and H3 in the nucleosome structure. We find that the positions of the α1 and α2 helices of Cse4 in the free Cse4/H4 dimer deviate from those in the ScScm3/Cse4/H4 complex (Fig. 3C, D). In addition, the α2 helix of H4 in the free Cse4/H4 dimer does not align well with the corresponding region of H4 in the canonical nucleosome structure (Fig. 3E, F).

Figure 3.

NMR structure of the folded region in the single-chainSc Cse4/H4 dimer at pH 5.6. (A) and (B) Overlay of the folded region of the Sc Cse4/H4 dimer from 10 calculated low energy structures. (C) and (D) Comparison of the folded regions of Cse4/H4 in the dimer and in the Scm3/Cse4/H4 trimer complex. (E) and (F) Comparison of the folded regions of Cse4/H4 in the dimer and those of H3/H4 in the nucleosome structure. The structures are aligned on H4.

Equilibrium between the Cse4/H4 dimer and the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer

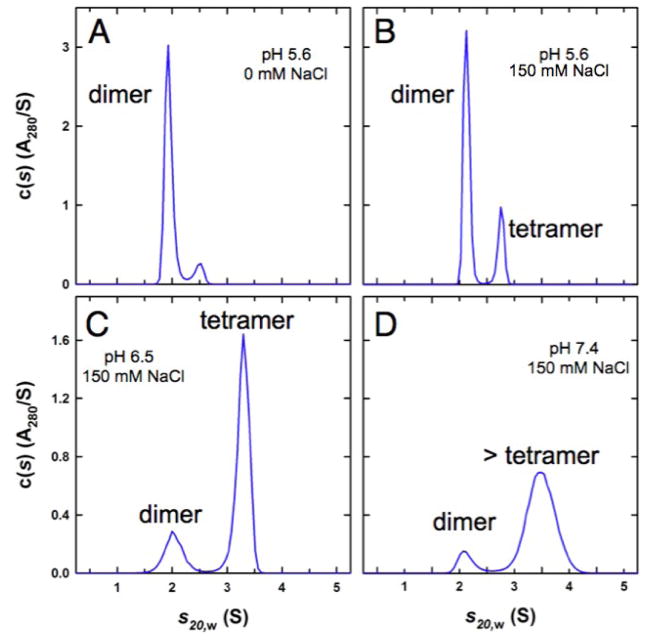

We next investigated the intrinsic properties of the Cse4/H4 complex in the absence of Scm3 at different salt concentration and pH values. At pH 5.6 (50 mM MES) without salt, velocity sedimentation experiments show that the Kl and Sc Cse4/H4 dimers are dominantly populated in solution (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5A). Larger molecular weight species became more populated as salt concentration or pH was increased (Fig. 4B–D and Fig. S5B–D). This additional species has an apparent molecular weight larger than that of the Cse4/H4 dimer but smaller than or close to that of the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer (Fig. 4B,C and Fig. S5B,C), likely representing a (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer that is in fast exchange with the Cse4/H4 dimer. At pH 7.4 and in the presence of 150 mM NaCl, the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer seems to be in equilibrium with a species that has a larger molecular weight as indicated by a broader peak and larger S20,w. In contrast, human CENP-A and H4 predominantly form a CENP-A/H4 dimer at pH 4.5 (50 mM NaAc) and a (CENPA/H4)2 tetramer at pH 5.6 in the absence of salt (Fig. S5E, F).Thus, around neutral pH the (CenH3/H4)2 tetramer is the predominant form when chaperone amount is limiting, and could be incorporated into ectopic sites in the chromosome (21, 22). In budding yeast, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Psh1)targets the free Cse4 for proteolysis by binding to the CATD region of Cse4 (21, 22), suggesting that Psh1, like Scm3, may also dissociate the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer.

Figure 4.

pH- and salt dependent equilibria between the two-chain Cse4/H4 dimer and the Cse4/H4 tetramer. Velocity sedimentation analyses of the KlCse4/H4 complexes at different pH and salt concentrations. (A) pH 5.6 and 0 mM NaCl. (B) pH 5.6 and 150 mM NaCl. (C) pH 6.5 and 150 mM NaCl. (D) pH 7.4 and 150 mM NaCl. Broadening of the peak indicates the exchange of different oligomers within the time scale of the sedimentation process. In all cases, the species at ~2.0 S has a best-fit molar mass consistent with a Cse4/H4 dimer. The faster sedimenting species represents the reaction boundary describing the fast exchange of the tetramer and the dimer, except in the case of (D) where the broader and faster sedimenting peak is resolved into tetramers and possibly hexamers.

Mutational analysis of CenH3 recognition by the chaperones

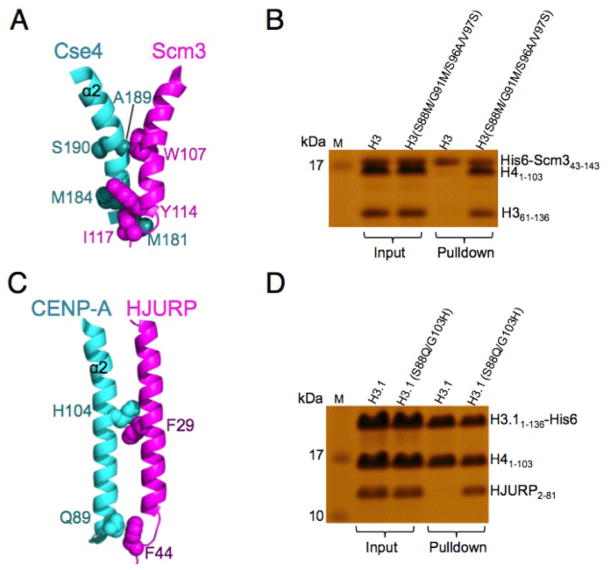

We have previously shown that four Sc Cse4-specific residues (M181, M184, A189, S190) in the α2 helix N-terminal region are necessary and sufficient for Scm3 recognition (Fig. 5A) (11). These four residues are located within the CATDrequired for CenH3 deposition in the centromere (16). As these four residues are fully conserved in Kl Cse4, we used them to replace the corresponding residues in the Kl H3 and found that His-tagged Kl Scm3 can also recognize the Kl H3(S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S)/H4dimer (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

The N-terminal region of the α2 helix of CenH3 is sufficient for specific recognition by the chaperone. (A) Regions important for interaction between the N-terminal region of α2 helix of Cse4 and the C-terminal region of the αN helix of Scm3. (B) Pull-down experiments showing that KlScm3 can recognize the Kl H3(S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S)/H4dimer. (C) Structural illustration of the interactions at the N-terminal region of the α2 helix of CENP-A with the C-terminal region of αN helix HJURP. (D) Pull-down experiments showing that HJURP can recognize the H3.1(S88Q/G103H)/H4dimer.

In contrast, only one residue (Sc Cse4 A189 or Kl Cse4 A144) of the four Cse4-specific residues is conserved in CENP-A. In the crystal structure of the Hs HJURP/CENP-A/H4 complex (13), three CENP-A-specific residues (Q89, H104, and L112) in the α2 helix of CENP-A interact with three HJURP residues (F44, F29, Ll8). Two of them (Q89, H104) are in the N-terminal half region of the α2 helix (Fig. 5C). We used these two residues to substitute for the corresponding residues in Hs H3.1 and tested the binding of Hs H3.1(S88Q/G103H)/H4 to HJURP. We found that this double mutation is sufficient for recognition of the histone dimer by the HJURP chaperone in a pull-down experiment (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

Our NMR results show that the Sc and Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complexes have similar structures with partially unfolded histone-folds for the histones, which is consistent with the high sequence homology between Sc and Kl histones and chaperones (12). The results confirm our earlier speculation that crystal packing along with the use of a shorter Kl Scm3 construct may have led to the canonical histone fold in the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4complex (14, 15). Indeed, Cho and Harrison have acknowledged that the region following the αN helix of Scm3 in the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex is likely affected by crystal packing since it shows no interactions with the histones in the same complex (12). In addition, Cho and Harrison crystallized the Kl (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer from a solution of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex at pH 8.5, indicating that crystal packing even conduces to form the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer by dissociating Scm3 from the Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex (12).

The solution structure of the Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex and the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex have different implications for structural models of the centromeric nucleosome (23–26). For example, the crystal structure of the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex has been used to support the hemisome model of the Sc centromeric nucleosome since the artifactual structural regions observed for Kl Scm3 in the Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex block DNA binding and a formation of the Kl (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer (23–25), while the solution structure of Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 is cited to support the octasome model (26). More importantly, comparison of the structures of the Sc Scm3/Cse4/H4 and Hs HJURP/CENP-A/H4 complexes now reveals that both Scm3 and HJURP use the region following the N-terminal helix of the chaperone to prevent DNA from binding to the L1 loop of CenH3 and the L2 loop of H4, even though the amino acid sequences and the detailed structures in this region are not conserved.

Our studies also show that partial unfolding of Cse4/H4 is coupled with the dissociation of the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer to the Cse4/H4 dimer in a pH- and salt-dependent manner and the unfolded regions of Cse4/H4 in the Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex are also unfolded in the free Cse4/H4 dimer. In addition, we observe conformational changes of the folded region of Cse4/H4 in different complexes. These results indicate that the partial unfolding in the Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex reflects the intrinsic property of the Cse4/H4 dimer and Scm3 binding induces conformational changes in Cse4/H4. A fully folded histone fold of Cse4/H4 may only occur in the context of other histones and DNA when forming a nucleosome or crystal.

The proposal that CENP-A residue S68 in the α1 helix is the primary specificity determinant for HJURP recognition is based onpull-down experiments: CENP-A with the S68Q mutation fails to bind to HJURP, whereas Hs H3 with the inverseQ68S mutation is recognized by HJURP(13). The mutation effects, however, were not observed in a later study using chromosome-tethering assay, biochemical reconstitution, and size exclusion chromatography(17). Instead, the combination of the two C-terminal substitutions (H104 and L112) in the α2 helix of CENP-A with either one of the two substitutions in the N-terminal portion of the α2 helix (Q89) or the L1 loop (N85) is sufficient to target CENP-A to the chromosomal HJURP array. Our mutation studies reveal that the N-terminal region of the α2 helix of CenH3, which includes either four Cse4-specific residues or two CENP-A-specific residues, is sufficient for chaperone recognition. Thus, while the sequence and overall structures of the CenH3/chaperone complexes have changed significantly throughout evolution, the structural region for chaperone recognition has largely been maintained.

In summary, Cse4/H4 in the budding yeast Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex has a partially unfolded structure, reflecting the intrinsic property of the Cse4/H4 dimer. Partial unfolding in the Cse4/H4 dimer is coupled with the dissociation of the (Cse4/H4)2 tetramer. Scm3 associates with the partially unfolded Cse4/H4 dimer and induces structural changes in the histones. Both Scm3 and HJURP use the region following the αN helix to block the DNA-binding sites in CenH3/H4. The N-terminal portion of the CenH3 α2 helix contains the conserved chaperone recognition region. Our results provide an example of how protein complexes can evolve their sequences and overall structures while maintaining local regions for specific recognition.

Materials and Methods

Gene cloning of histones and chaperones

For efficient expression and purification of histones and chaperones, the codon-optimized DNAs encoding a single chain of His6-Cse4Kl 106–183-LVPRGS-H4Kl 30–103 and His6-SSGLVPRGS-CENP-A60–140–LVPRGS-HJURP2–81 were synthesized commercially (Genewiz, USA) and cloned into a pET vector (Novagen, USA). The LVPRGS is the sequence recognized by thrombin, which cuts between R and G. The mutant construct, His6-Cse4Kl 106–183(L158G/L159G/L161G/H162G)-LVPRGS-H4Kl 30–103, was derived from the above construct by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, USA). Also, the DNAs for His6-SSGLVPRGS-Scm3Kl 43–143 and H4Kl 1–103 were synthesized and cloned into a pET vector, respectively. The DNAs encoding H3Kl 61–136 and H3Kl 61–136 (S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S) were amplified from the plasmids containing wild-type H3Sc(with amino acid sequence identical to H3Kl) or mutant H3Sc(S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S) (11) and sub-cloned into a pET vector, respectively. The cDNA encoding full-length H3.1 was amplified from SuperScript human brain cDNA library (Life Technologies, USA) and cloned into a pET vector. Full-length human H4 was a gift from Dr. Carl Wu. Human H41–15-LVPRGS-H422–103 and full length H3.1 (S88Q/G103H) were produced by site-directed mutagenesis from the full length human H4 and H3.1 constructs using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, USA). The plasmid encoding a single chain His6-KK-Cse4Sc 151–207-LVPRGS-H4Sc 45–103 was described in our early work (11). A list of constructs used in this study is summarized in Table S1.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

E. Coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIPL (Stratagene, USA) was used for the expression of histone and chaperone proteins. The purification of H3Kl 61–136, H3Kl 61–136 (S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S), H4Kl 1–103, H4Hs 1–103, H4Hs 22–103 followed the published procedure (27). The His6-tagged proteins were purified as described in our earlier work (11). Isotope-labeled proteins for NMR studies were expressed by growing E. coli cells in M9 media with 15NH4Cl, U-13C6-Glucose, and with or without D2O as the sole source for nitrogen, carbon, and deuterium, respectively.

Reconstitution of protein complexes

To prepare the Scm3Kl/Cse4Kl/H4Kl complex, lyophilizedHis-taggedScm3Kl 43–143 and His6-Cse4Kl 106–183-LVPRGS-H4Kl 30–103 (1:1 ratio) were mixed together in 6 M GudHCl and then dialyzed overnight against a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl and 0.5 M NaCl (pH 7.4) at 4°C. Thrombin was then added to the solution to cleave the linker. The proteins were denatured again in 6 M GudHCl and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer at 4°C. The soluble fraction was concentrated and subjected to gel filtration on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare, USA). The eluted complex was concentrated and buffer exchanged with 50 mM MES (pH 5.6). The GS-Scm3Kl 43–143/His6-Cse4Kl 106–183 (L158G/L159G/L161G/H162G)-LVPR/GS-H4Kl 30–103 was also prepared in the same way.

To make the complex containing His6-Cse4Kl 106–183-LVPR and GS-H4Kl 30–103, lyophilized His6-Cse4Kl 106–183-LVPRGS-H4Kl 30–103 was unfolded in 6 M GuHCl and refolded in 50 mM MES (pH 5.6) at 4°C. After a complete cleavage of the linker by thrombin, the complex was denatured again in 6 M GuHCl and dialyzed overnight against 10 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) at 4°C. After purification by gel filtration under the same condition, the sample was buffer exchanged with 50 mM NaAc (pH 4.7), 50 mM MES (pH 5.6), 50 mM MES (pH 5.6) and 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM phosphate (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl, respectively.

To prepare human HJURP/CENP-A/H4 complex, lyophilized proteins His6-SSGLVPRGS-CENP-A60–140–LVPRGS-HJURP2–81 and H4Hs 1–103 (1:1 ratio) were first denatured in 6 M GuHCl, mixed together and dialyzed overnight against a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 2 M NaCl, 5 mM βME (β-mercaptoethanol) at 4°C. After a complete cleavage of the linker by thrombin, the complex was denatured again in 6 M GuHCl and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer at 4°C. After purification by gel filtration under the same condition, the complex was concentrated and buffer exchanged with a solution containing 50 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM βME, and 10% D2O at pH 7.0 (NMR sample) and another solution containing 50 mM MES, 5 mM βME, and 10% D2O at pH 5.6 (NMR sample). Human GS-HJURP2–81/GS-CENP-A60–140-LVPR/GS-H422–103 complexes at pH 5.6 and pH 7.0 for NMR studies were also prepared as above. The sample containing GS-CENP-AHs 60–140-LVPR and GS-H4Hs 22–103 in 50 mM MES (pH 5.6) and 5 mM βME was made in the same way using lyophilized proteins GS-CENP-AHs 60–140-LVPR and GS-H4Hs 22–103 (1:1 ratio).

Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments

A complex containing GS-Scm3Kl 43–143, His6-Cse4Kl 106–183 (L158G/L159G/L161G/H162G)-LVPR and GS-H4Kl 30–103 was studied in 50 mM MES (pH 5.6) at a concentration corresponding to a measured A280 of 0.80 (35 μM). In addition, samples containing His6-Cse4Kl 106–183-LVPRand GS-H4Kl 30–103 were studied at a dimer concentration of 38 μM in different buffers, including 50 mM MES (pH 5.6), 50 mM MES (pH 5.6) and 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM phosphate (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.4) and 150 mM NaCl.

Sedimentation velocity experiments were conducted at 20.0°C on a Beckman Optima XL-A or Beckman Coulter ProteomeLab XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge. 400 μl of each of the samples were loaded in 2-channel centerpiece cells and analyzed at a rotor speed of 50 krpm with scans collected at approximately 5 minute intervals. Data were collected using the absorbance optical system in continuous mode at 280 nm using a radial step size of 0.003 cm. Data was also collected using the Rayleigh interference detection system when possible. All data were analyzed in SEDFIT 12.7 (28) in terms of a continuous c(s) distribution of Lamm equation solutions covering a maximal s20,w range of 0 – 10 with a resolution of 20 points per S and a confidence level of 0.68. Excellent fits were obtained with RMSD values ranging from 0.0034 – 0.0047 absorbance units. Solution densities ρ and viscosities η were measured as described (11), or calculated in SEDNTERP 1.09 (29). Partial specific volumes v were calculated in SEDNTERP 1.09 and corrected to account for the 15N, 13C and/or 2H isotopic substitution. Sedimentation coefficients s were corrected to s20,w.

NMR experiments and structure calculation

NMR experiments were performed on Bruker 700 and 900 MHz spectrometers at 30°C (Kl Scm3/Cse4/H4) or 35°C (Sc Cse4-H4). The following experiments were recorded: 2D [1H, 15N]-HSQC, [1H, 15N]-TROSY; 3D CBCANH, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HBHACONH, HCCH-TOCSY, CCH-TOCSY, CCC(CO)NH, [1H,15N]-NOESY-HSQC, [1H, 13C]-NOESY-HSQC; TROSY version 3D, HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCO, HN(CA)CO. The spectra were processed using NMRPipe (30) and analyzed with Sparky (Goddard & Kneller). Structure calculation was done as described in our earlier work (11). The program PROCHECK_NMR (31) was used to evaluate the quality of the calculated structures.

Pull-down experiments

Pull-down experiments were carried out in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM imidazole, 2 M NaCl, 5 mM βME at 4°C. 5 μM H3/H4 (Kl H361–136/H41–103 or Hs H3.11–136-His6/H41–103) or H3 mutant/H4 (Kl H361–136 (S88M/G91M/S96A/V97S)/H41–103 or Hs H3.11–136 (S88Q/G103H)-His6/H41–103) with corresponding equal molar amount of histone chaperone Kl His6-SSGLVPRGS-Scm343–143 or Hs GS-HJURP2–81 were incubated with Ni-NTA (Qiagen) beads for 1 hr, washed 5 times, eluted from the beads with 500 mM imidazole, and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Supplementary Material

Budding yeast K. lactis Scm3/Cse4/H4 complex is partially unfolded in solution.

Free K. lactis Cse4/H4 dimer is partially unfolded.

Scm3 and HJURP use a similar structural region to block DNA binding.

CenH3 has a structurally conserved chaperone recognition region.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Shipeng Li for purification of proteins and Dr. Jemima Barrowman for editing the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cleveland DW, Mao Y, Sullivan KF. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell. 2003;112(4):407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henikoff S, Ahmad K, Malik HS. The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science. 2001;293:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1062939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuguchi G, Xiao H, Wisniewski J, Smith MM, Wu C. Nonhistone Scm3 and histones CenH3–H4 assemble the core of centromere-specific nucleosomes. Cell. 2007;129:1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camahort R, et al. Scm3 is essential to recruit the histone h3 variant cse4 to centromeres and to maintain a functional kinetochore. Mol Cell. 2007;26(6):853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoler S, et al. Scm3, an essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromere protein required for G2/M progression and Cse4 localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10571–10576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703178104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Pulido L, Pidoux AL, Ponting CP, Allshire RC. Common ancestry of the CENP-A chaperones Scm3 and HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams JS, Hayashi T, Yanagida M, Russell P. Fission yeast Scm3 mediates stable assembly of Cnp1/CENP-A into centromeric chromatin. Mol cell. 2009;33:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pidoux AL, et al. Fission yeast Scm3: A CENP-A receptor required for integrity of subkinetochore chromatin. Mol Cell. 2009;33:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foltz DR, et al. Centromere-specific assembly of CENP-a nucleosomes is mediated by HJURP. Cell. 2009;137:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunleavy EM, et al. HJURP is a cell-cycle-dependent maintenance and deposition factor of CENP-A at centromeres. Cell. 2009;137:485–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Z, et al. Structural basis for recognition of centromere histone variant CenH3 by the chaperone Scm3. Nature. 2011;472:234–237. doi: 10.1038/nature09854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho US, Harrison SC. Recognition of the centromere-specific histone Cse4 by the chaperone Scm3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9367–9371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106389108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu H, et al. Structure of a CENP-A-histone H4 heterodimer in complex with chaperone HJURP. Genes Dev. 2011;25:901–906. doi: 10.1101/gad.2045111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng H, Zhou Z, Zhou BR, Bai Y. Structure of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromeric histones Cse4-H4 complexed with the chaperone Scm3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109548108. author reply E597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai Y, Zhou Z, Feng H, Zhou BR. Recognition of centromeric histone variant CenH3s by their chaperones: structurally conserved or not. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3217–3218. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.19.17077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black BE, et al. Structural determinants for generating centromeric chromatin. Nature. 2004;430:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature02766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett EA, et al. HJURP uses distinct CENP-A surfaces to recognize and to stabilize CENP-A/histone H4 for centromere assembly. Dev Cell. 2012;22:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bax A, Grzesiek S. Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wishart DS, Sykes BD. The 13C chemical-shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarzinger S, et al. Sequence-dependent correction of random coil NMR chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2970–2978. doi: 10.1021/ja003760i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewawasam, et al. Psh1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the centromeric histone variant Cse4. Mol Cell. 2010;40:444–454. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranjitkar, et al. An E3 ubiquitin ligase prevents ectopic localization of the centromeric histone H3 variant via the centromere tageting domain. Mol Cell. 2010;40:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henikoff S, Henikoff JG. “Point” centromeres of Saccharomyces harbor single centromere-specific nucleosomes. Genetics. 2012;190:1575–1577. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krassovsky K, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Tripartite organization of centromeric chromatin in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:243–248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118898109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shivaraju M, et al. Cell-cycle-coupled structural oscillation of centromeric nucleosomes in yeast. Cell. 2012;150:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Colmenares SU, Karpen GH. Assembly of Drosophila centromeric nucleosomes requires CID dimerization. Mol Cell. 2012;45(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuck P. On the analysis of protein self-association by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Anal Biochem. 2003;320(1):104–124. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole JL, Lary JW, Moody PT, Laue TM. Analytical ultracentrifugation: sedimentation velocity and sedimentation equilibrium. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;84:143–179. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.