Abstract

Background

Task shifting, defined for this review as the shifting of ART initiation and management from physicians to nurses, has been proposed as a possible method to increase access to HIV treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective

To critically evaluate the literature on task shifting, determining if there is evidence to support this view.

Methods

A systematic search of the literature was undertaken, with both peer reviewed publications and conference abstracts presenting original data eligible for inclusion. Studies were evaluated according to methodology and discussion of confounding factors.

Results

We identified 25 articles which evaluated the effect of task shifting on access to ART. The evidence was mixed. Although there is a significant body of field reports indicating that task shifting increases access, these studies were of low methodological quality. The only randomized controlled trial included in this review did not find that task shifting increased in access.

Conclusion

Task shifting appears to be most effective at increasing access when combined with other interventions and financial support. There is a need for more research into the effects of task shifting policies, especially randomized controlled trials and high quality cohort studies.

Keywords: task shifting, antiretroviral therapy, nurse provided treatment, substitution of physicians, access to HIV treatment

Introduction

While the spread of HIV/AIDS is a global epidemic, Sub-Saharan Africa is the region most highly affected.1 One factor limiting the scale up of antiretroviral therapy and other HIV services is the severe health care worker shortage facing Africa.2 Task shifting, the gradual transfer of ART management and initiation from doctors to nurses and other non-physician clinicians, has been proposed to address this problem. Task shifting has been well studied in both high and low resource settings and good patient outcomes have been consistently reported. A 2010 systematic review of task shifting with regard to antiretroviral therapy concluded that nurse managed ART offered high quality care equivalent to physician managed care.2 Because of the existing strong evidence and consensus in the literature that task shifting has good outcomes, this systematic review will not focus on evaluating patient outcomes. Instead, this review will evaluate whether task shifting of ART initiation and management from physicians to nurses increases access to antiretroviral therapy, the primary purpose cited for the implementation of task shifting policies.

Methods

To identify articles for this review, three search themes were combined with the boolean operator “and”. The first search theme was centered around task shifting, which was combined with the theme of HIV and the theme of antiretrovirals. Multiple synonyms for each theme were used. The following databases were searched until February 2012: PubMed, South African Health Research Index, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Popline, CINAHL, EMBASE, AIDSLine, Social Science Citation Index and Arts & Humanities Citation Index. The abstract databases of the International AIDS Society Conferences, the Conferences on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections and the conferences of the International Society of Sexually Transmitted Disease Research were searched. Bibliographies of relevant papers were also reviewed and a grey literature search was conducted. Literature had to be applicable to Sub-Saharan Africa or low resource settings and had to measure access to antiretroviral therapy. Patient enrollment was used as the primary indicator of access while wait times, workforce and loss to follow up were evaluated as secondary measures of access. Articles identified as relevant to access to ART were evaluated for quality according to methodology and discussion of confounding factors.

Results

Search Process

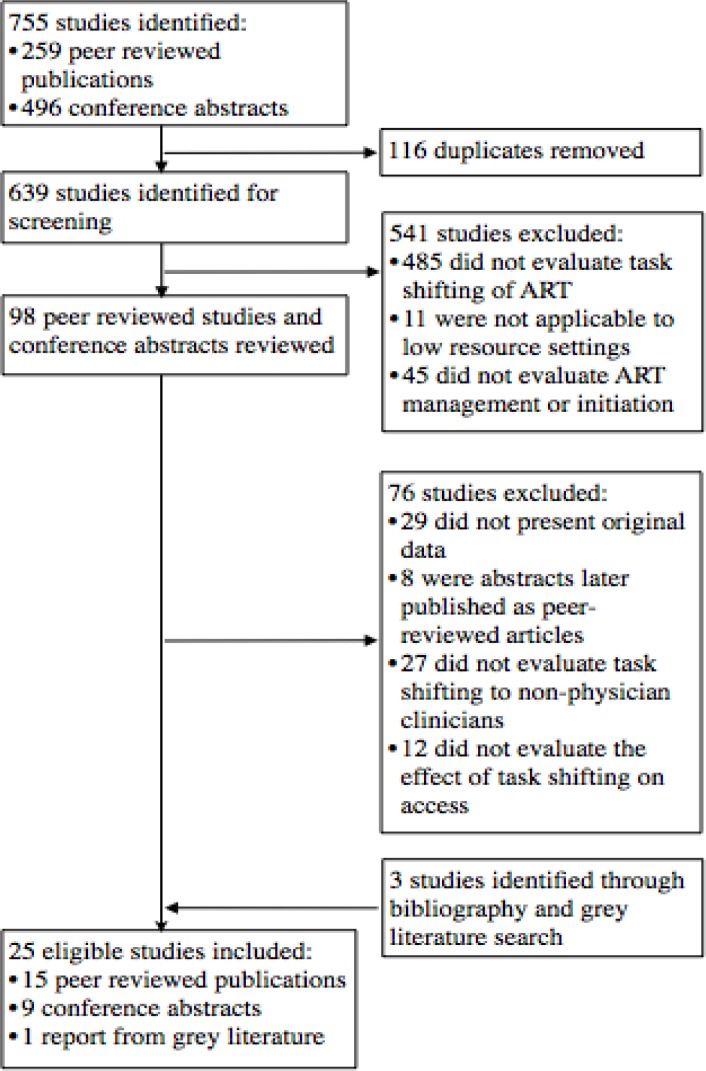

Following search and screening, twenty-five studies were chosen for inclusion in the review. (Figure 1) Due to the heterogenous nature of the results, a quantitative meta-analysis would have been inappropriate. Instead, a qualitative synthesis was used to evaluate the existing evidence.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of serach and screening process

Wait times and Workforce

There have been many studies examining the effects of task shifting on secondary measures of access including wait times, workforce hours and retention in care (loss to follow up). The evidence is mixed. Wanyenze et al.3 found that wait times in nurse managed clinics were significantly longer than those in physician managed clinics while two contradictory studies found that task shifting resulted in a decrease in mean wait time.4, 5 O'Brien et al. measured the effect that task shifting has on physicians' workload in Rwanda on the assumption that a reduced workload would allow physicians to redirect their time to enrolling patients.6 They calculated that without task-shifting policies, Rwanda will need to increase their physician workforce by 52% to hit ART enrollment targets. With task shifting policies, this increase is reduced to 11%.

Loss to Follow up

There is a significant body of evidence indicating that nurse managed care increases retention and reduces loss to follow up. Cohort studies from Swaziland7, Malawi8, Ethiopia,9 Kenya10 and South Africa11 all found that clinics with task-shifting policies had reduced loss to follow up rates compared to similar clinics lacking task-shifting policies. Cohort studies in Rwanda12, Ethiopia13 and South Africa14 found that the retention rates at nurse managed clinics, 89%, 91% and 95% respectively, were above the national average in each country.

Patient Enrollment

There are a number of field reports suggesting that task shifting can be used to increase enrollment in antiretroviral therapy on a district and nation wide scale. In Thyolo, Malawi, task shifting from doctors to non-physician clinicians (primarily nurses) doubled ART initiation and allowed for universal access by 2009.15 In Lusikisiki, South Africa, ART initiation by nurses within rural clinics allowed for the doubling of initiation of patients.16 When this form of task shifting was reversed in 2006, with ART initiation restricted to physicians, ART initiation rates declined.17 Task shifting policies in Zambia18 Lesotho19 and Mozambique20 were all reported to allow for a dramatic increase in patient enrollment. Studies in Haiti21, South Africa22 and Cameroon 23 all found that task shifting policies reduced waiting lists for HIV treatment. Field reports from Botswana24, Uganada25 and Swaziland26 observed task shifting policies increased the enrollment of patients at primary clinics.

The only randomized controlled trial evaluating task shifting's effect on access recently reported initial data. The Streamlining Tasks and Roles to Expand Treatment and Care for HIV (STRETCH) trial randomly assigned 16 clinics in the Free State Province of South Africa to put in place policies of nurse managed and initiated HIV treatment and compared them to fifteen clinics which kept conventional physician care.27 This trial occurred under the normal constraints of a public health system in a middle income country; training for nurse initiated ART was hindered by the high turnover rate and there was also difficulty in maintaining adequate ART supplies. Contrary to expectations, nurse initiation of antiretroviral therapy did not reduce waiting list mortality, with a hazard ratio of 0.92 for death (p=0.532) between nurse initiated and physician initiated clinics. However, this effect varied with patients' CD4 levels. The waiting list mortality for patients with CD4 <200 was equivalent for nurse and physician initiated clinics (HR = 1.0) while the waiting list mortality for patients with CD4 levels between 200 and 350 was reduced, although not significantly, at nurse initiated clinics (HR = 0.73, p = 0.052). There is an apparent contradiction between the evidence from this randomized controlled trial and the body of field reports, which will be elaborated on further in the discussion.

Discussion

The reported ability of task shifting to improve access to ART varies according to the measurement of access and the quality of the study. There is strong and consistent evidence that task shifting reduces loss to follow up and increases retention in care from studies in multiple countries in sub-saharan Africa. This has been attributed to the decentralization associated with task shifting.16 Providing treatment closer to patients' homes removes barriers associated with travel such as costs and taking time off work.16 As clinicians tend to be concentrated in urban areas, the availability of physicians to prescribe ART at peripheral sites can be the limiting factor for treatment.16 Task shifting can thus strengthen the positive effects of decentralization by increasing the availability of clinicians at peripheral sites.

Field reports from multiple countries including Swaziland, Uganda, Rwanda, South Africa and Lesotho have all found that task shifting increases patient enrollment in ART. However, many of these studies suffer from significant methodological flaws such as a lack of comparison group. Further increasing the difficulty in interpreting these reports is the presence of confounding factors. Task shifting to nonphysician clinicians was typically only one of several interventions reported in these studies. Many included separate task shifting to lay workers15, 16, the use of first line tenofovir19 and community support22. These interventions have also benefited from substantial external funding from NGOs and may not reflect what is feasible within the constraints of a public health system28. The STRETCH randomized controlled trial, on the other hand, was conducted within all of the usual constraints of an underfunded public health system. Initial results, however, have indicated that it did not improve access to ART, as measured by a statistically significant decrease in waiting list mortaliyt27. A possible explanation for this apparent lack of effect is the difficulty in training nurses for their new roles and the high staff turnover throughout the trial.27 Only 26% of patients in the nurse initiated arm of the trial were actually initiated by nurses, suggesting that the STRETCH intervention was not fully implemented in the nurse initiating clinics27. The lack of a corresponding shifting of tasks from nurses to lay workers with the introduction of nurse initiated ART may also have overburdened nurses, inhibiting access to ART. In addition, the doctor initiated arm of the trial was able to dramatically increase prescribing rates during the trial.27

With the lack of high quality evidence that the STRETCH trial would have provided, it is difficult to validate the current expansion of nurse initiated care that is occurring in South Africa, Lesotho and other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the discrepancy between the results of the STRETCH trial and the field reports suggest external factors that may influence the efficacy of task shifting policies. The field reports suggest that improved access to ART came through a combination of task shifting policies with other interventions such as decentralization, task shifting to lay workers and community support, interventions lacking in the STRETCH trial. This suggests that task shifting should not be considered in isolation but rather as a part of the solution to the severe health care worker shortage in Africa. Task shifting to lay workers, for example, may be critical to ensuring that nurses' workloads stay manageable with the additional responsibilities of providing HIV treatment.16 Without the further inclusion of lay workers, increased access to treatment may be limited by the availability of nurses16. Similarly, measures such as increased pay for health care workers to improve retention, investment in long term training and increases in funding may increase the likelihood that task shifting policies can improve access29. Additionally, there is a significant body of evidence demonstrating equivalent outcomes between nurse and physician initiated ART2 and there is evidence suggesting potential cost savings through the adoption of task shifting policies.2 In this view, task shifting policies should be considered as an effective method of providing ART but not an effective method of increasing access to ART unless combined with significant training, support and other interventions.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this review. Although this review focused on the task shifting of ART management and initiation, these two terms encompass a broad range of tasks including testing, prescription of medicine, dispensing medicine, detection of complications and referral. Studies which refer to the same form of task shifting may, in practice, implement highly dissimilar forms.2 While this hinders the comparison of studies, it may explain the variation in access seen in this review. Similarly, there can be substantial variation in the training and competencies of nurses or nonphysician clinicians between different countries and regions. Differing workloads prior to implementation of task shifting can also impact the ability of nurses to increase initiation rates, as previously mentioned.

There is substantial evidence that task shifting provides equivalent outcomes as traditional physician managed treatment2 and this review provides further support for task shifting policies when implemented with additional strengthening programs. However, there remains resistance among many health authorities to implementing task shifting policies. Professional groups, for example, have objected to what they view as an encroachment of their authority.17 If task shifting is to be adopted across Sub-Saharan Africa, it is critical that research be done to identify these barriers and methods of removal.

Conclusion

Although there is a large body of literature evaluating the effect of task shifting on access to antiretroviral therapy, much of it is hampered by poor methodology and the presence of confounding factors. A recent randomized controlled trial comparing clinics with nurse initiated ART against clinics with only physician initiated ART failed to find a statistically significant increase in access to ART. However, there is evidence that when combined with other interventions to strengthen the workforce and increase funding, task shifting can be effective at improving access. Therefore, task shifting policies should be considered by nations attempting to improve access but only as part of a broader set of efforts to improve HIV treatment. There is a need for more research into the effects of task shifting policies, especially randomized controlled trials and high quality cohort studies. However, trials comparing HIV treatment with and without task shifting policies may pose ethical issues that should be carefully considered prior to implementation. Studies comparing the efficacy of various combinations of task shifting policies would also be valuable and could help determine which support and training mechanisms are necessary to provide high quality care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies considered in this systematic review

| Source | Location | Design/Size | Measurement | Outcomes | Methodological limitations |

| Assefa et al. 20119 | Ethiopia | Cohort/184 978 |

Loss to follow up |

Nurse managed care reduced loss to follow up but there was a high cost for training and mentorship |

Facilities were not selected randomly, loss to follow up was not investigated |

| Bedelu et al. 200716 | South Africa |

Cohort/1025 | Enrollment | Task shifting policies doubled enrollment |

Many other program improvements used |

| Bemelmans et al. 201015 |

Malawi | Cohort/23 361 |

Enrollment | Task shifting double enrollment to 23 361 patients, allowed for universal access with in Thylolo, Malawi |

Many other program improvements used |

| Brennan et al. 201111 | South Africa |

Cohort/2772 | Loss to follow up |

Down referral to nurse managed treatment resulted in reduced loss to follow up rates |

Single clinic examined |

| Cohen et al. 200919 |

Lesotho | Cohort/13 243 |

Enrollment | Annual enrollment doubled from 2006 to 2008 with no increase in human resources through task shifting |

Other improvements including early initiation of ART, external funding |

| Fairall et al. 201227 |

South Africa |

RCT/15 571 |

Enrollment | No significant reduction in waiting list mortality for task shifting clinics (HR = 0.92 for death, p=0.53) |

Only 26% of patients in the nurse cohort were initiated by a nurse |

| Fredlund et al. 200722 |

South Africa |

Cohort/1311 | Enrollment | Decentralization to a primary clinic improved access, nurse initiation of ART prevented waiting lists |

Decentralization and community support were used |

| Hartman et al. 201113 |

Ethiopia | Cohort/80 000 |

Enrollment | Nurse managed ART services provided to 80 000 people, loss to follow up rate is 9% compared to 20% nationally |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group, significant external funding |

| Hulela et al. 200824 |

Botswana | Cohort/20 000 |

Enrollment | Task shifting increased access to ART, allowed 20 000 patients to receive treatment at rural clinics |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group or discussion of confounding factors |

| Humphreys et al. 20107 |

Swaziland | Cohort/474 | Loss to follow up |

Nurse managed ART resulted in increased clinic attendance and retention |

Decentralization also present |

| Ivers et al. 201121 |

Haiti | Survey/11114 | Enrollment | 11 114 people were enrolled in ART therapy over five years using a task shifting model; Currently no waiting lists for treatment; Low rates of loss to follow up |

External funding, observational study |

| Iwu et al. 20105 |

Nigeria | Cohort/— | Wait times |

Wait times decreased by 62%, physician workload decreased by 41% |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group |

| Kamiru et al. 201026 |

Swaziland | Cohort/534 | Enrollment | Establishments of 7 clinics with nurse ART management allowed for the enrollment of 534 patients |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group, decentralization also present |

| Loubiere et al. 200923 |

Cameroon | Survey/2566 | Enrollment | Patients were less likely to be treated in central hospitals lacking a task shifting policy |

Survey, confounding factors, different forms of task shifting used |

| McGuire et al. 20118 |

Malawi | Cohort/10 822 |

Loss to follow up |

Nurse managed care resulted in reduced loss to follow up |

Not peer reviewed, possible confounding factors not described |

| Morris et al. 200918 |

Zambia | Cohort/71 000 |

Enrollment | Task shifting allowed for the enrollment of 71 000 patients over 19 urban sites. |

Significant external funding, intensive use of resources |

| Namugrwere et al. 201125 |

Uganda | Cohort/1992 | Enrollment | Training of two nurses at a clinic resulted in enrollment increasing by 19.7% |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group, only a single clinic |

| O'Brien et al. 20086 |

Rwanda | Modeling/3194 | Workforce | Task shifting would reduce Rwanda's increase in national physician capacity to reach its ART targets by 41% |

Not peer reviewed, model based off of three non-representative clinics |

| O'Connor et al. 201114 |

South Africa |

Cohort/3361 | Loss to follow up |

Retention at a nurse managed down referral site in Johannesburg was 95% |

No comparison site, other improvements including decentralization |

| Sherr et al. 200920 |

Mozambique | Cohort/6000 | Enrollment | Facilities providing ART were able to triple within six months, |

No comparison group |

| Shumbusho et al. 200912 |

Rwanda | Cohort/3194 | Loss to follow up |

Patient retention in three nurse managed clinics (89%) was comparable to national average for similar size clinics (87%) |

No comparison site, patients were followed for relatively short periods |

| Wanyenze et al. 20103 |

Uganda | Time-motion study/689 |

Wait times |

Waiting time was longest a nurse managed clinics, nurses spent twice the time with patients compared with doctors, task shifting may not be efficient in terms of time |

Only compared one nurse managed clinic to two physician managed clinics |

| Were et al. 201110 |

Kenya | Cohort/11800 | Loss to follow up |

Clinics with task shifting had an 18% decreased risk of death/LTFU |

Not peer reviewed, two clinics, did not separate death from loss to follow up |

| Udegboka et al. 20094 |

Nigeria | Cohort/— | Wait times |

Average wait time reduced from ten hours to six hours through task shifting |

Not peer reviewed, no comparison group, only one district hospital considered |

| Zachariah et al. 200917 |

South Africa |

Cohort/1634 | Enrollment | When task shifting from doctors to nurses in Lusikisiki was reversed, ART initiation rates dropped |

Inconclusive, confounding factors not described in paper |

Acknowledgements

Connor A Emdin is the recipient of the Heaslip Scholarship from University of Toronto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.UNAIDS, author. Global Report on the AIDS Epidemic. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Human Resources for Health. 2010;8:83. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wanyenze RK, Wagner G, Alamo S, et al. Evaluation of the efficiency of patient flow at three HIV clinics in Uganda. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(7):441–446. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.N Udegboka HM-J. International AIDS Conference. Cape Town: 2009. Reduction of client waiting time through task shifting in Northern Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 5.E Iwu IE, Ezebuihe I, Caroline O, Umaru E, Gomwalk A, Moen M, Riel R, Johnson J. International AIDS Conference. Vienna: 2010. Task shifting - a strategic response to human resource for health crisis: qualitative evaluation of hospital based HIV clinics in North central Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Megan E, O'Brien JC, Binagwaho Agnes, Shumbusho Fabienne, Price Jessica. Nurse delivery of HIV care: Modeling the impact of taskshifting on physician demand. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphreys CP, Wright J, Walley J, et al. Nurse led, primary care based antiretroviral treatment versus hospital care: a controlled prospective study in Swaziland. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10:229. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.M McGuire GP, Goossens S, Heinzelmann A, Chikwaza O, Szumilin E, Berthelot M, Pujades-Rodriguez M. International AIDS Conference. Rome: 2011. Task-shifting of HIV care and ART initiation: three year evaluation of a mixed-care provider model for ART delivery. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assefa Y, Kiflie A, Tekle B, Mariam DH, Laga M, Van Damme W. Effectiveness and acceptability of delivery of antiretroviral treatment in health centres by health officers and nurses in Ethiopia. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2011;(1):24–29. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MC Were JG, Macharia S, Shen C, Yiannoutsos CT, Tierney WM. International AIDS Conference. Rome: 2011. Achieving quarterly physician visits for HIV-patients through taskshifting to nurses: a comprehensive prospective evaluation in Sub-Saharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brennan AT, Long L, Maskew M, et al. Outcomes of stable HIV-positive patients down-referred from a doctor-managed antiretroviral therapy clinic to a nurse-managed primary health clinic for monitoring and treatment. AIDS. 2011;25(16):2027–2036. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834b6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shumbusho F, van Griensven J, Lowrance D, et al. Task shifting for scale-up of HIV care: evaluation of nurse-centered antiretroviral treatment at rural health centers in Rwanda. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(10):e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000163. Oct. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AF Hartman WC, Konings E, Arega T. International AIDS Conference. Rome: 2011. National expansion of comprehensive HIV/AIDS services in Ethiopia: lessons learned from decentralizing HIV care and treatment to the community level in resource poor settings. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor C, Osih R, Jaffer A. Loss to follow-up of stable antiretroviral therapy patients in a decentralized down-referral model of care in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(4):429–432. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230d507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bemelmans M, Van Den Akker T, Ford N, et al. Providing universal access to antiretroviral therapy in Thyolo, Malawi through task shifting and decentralization of HIV/AIDS care. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15(12):1413–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedelu M, Ford N, Hilderbrand K, Reuter H. Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: the Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S464–S468. doi: 10.1086/521114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(6):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris MB, Chapula BT, Chi BH, et al. Use of task-shifting to rapidly scale-up HIV treatment services: experiences from Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Health Services Research. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen R, Lynch S, Bygrave H, et al. Antiretroviral treatment outcomes from a nurse-driven, community-supported HIV/AIDS treatment programme in rural Lesotho: observational cohort assessment at two years. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2009;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherr K, Pfeiffer J, Mussa A, et al. The role of nonphysician clinicians in the rapid expansion of HIV care in Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(Suppl 1):S20–S23. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbc9c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivers LC, Jerome JG, Cullen KA, Lambert W, Celletti F, Samb B. Task-shifting in HIV care: a case study of nurse-centered community-based care in Rural Haiti. PloS One. 2011;6(5):e19276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredlund VG, Nash J. How far should they walk? Increasing antiretroviral therapy access in a rural community in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S469–S473. doi: 10.1086/521115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loubiere S, Boyer S, Protopopescu C, et al. Decentralization of HIV care in Cameroon: increased access to antiretroviral treatment and associated persistent barriers. Health Policy. 2009;92(2–3):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.E Hulela JP, Ndwapi N, Ali A, Avalos A, Mwala P, Gaolathe T, Seipone K. International AIDS Conference. Mexico City: 2008. Task shifting in Botswana: empowerment of nurses in ART rollout. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namugrwere A. International AIDS Conference. Rome: 2011. The role of nurses in prescribing ARVs in the ART era, what is the way forward. [Google Scholar]

- 26.H Kamiru JV, Okello V, Mndzebele S, Bruce K, Preko P, Louis F. International AIDS Conference. Vienna: 2010. Increasing access to ART care and treatment through decentralization: early lessons from the Swaziland national AIDS program and ICAP experience. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairall L. 5th South African AIDS Conference. Durban: 2011. The effect of task-shifting antiretroviral care in South Africa: a pragmatic cluster randomised trial. STRETCH: Streamlining Tasks and Roles to Expand Treatment and Care for HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colvin CJ, Fairall L, Lewin S, et al. Expanding access to ART in South Africa: the role of nurse-initiated treatment. South African Medical Journal. 2010;100(4):210–212. doi: 10.7196/samj.4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philips M, Zachariah R, Venis S. Task shifting for antiretroviral treatment delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: not a panacea. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):682–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]