Abstract

Introduction

Isolated tuberculous epididymo-orchitis may closely mimic testicular tumour particularly in patients with no history of systemic TB thereby presenting a diagnostic and treatment challenges.

Case report

A 44-year old man presented with 4 months history of left scrotal mass and had left orchidectomy following a presumptive diagnosis of testicular tumour. Histopathological diagnosis of testicular tuberculosis was subsequently made. Although the patient was thereafter referred for antituberculosis treatment at the local tuberculosis treatment centre, he defaulted after commencing treatment.

Conclusion

Adequate evaluation of patients with testicular mass by means of abdominal and scrotal ultrasound coupled with fine needle aspiration cytology is critical to diagnostic accuracy, optimal treatment and possibility of avoiding surgery in those with testicular tuberculosis.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, epididymo-orchitis, ultrasound, cytology

Introduction

Tuberculous epididymo-orchitis is an important manifestation of genitourinary tuberculosis (GUTB).1 Many cases coexist with pulmonary TB or tuberculosis of other parts of lower genitourinary system including bladder, ureter and prostate.2 Isolated instances of tuberculous epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis is rare but when it occurs, a comprehensive assessment of the patient is mandatory.3 Recent surge in the prevalence of TB worldwide linked to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic has resulted in a concomitant increase in extrapulmonary TB of which GUTB accounts for up to 20% in endemic areas.4

Tuberculous epididymo-orchitis may mimic testicular tumours particularly in apparently healthy patients with no other clinical symptoms or signs. Thus this diagnostic dilemma may result to inappropriate surgical procedure for a potentially curable medical illness. High index of suspicion, scrotal ultrasound and fine needle aspiration could be quite helpful in the diagnosis.5 We report a patient with clinical diagnosis of testicular tumour who had excisional biopsy in a general hospital and the specimen was sent to Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Gombe. Histopathological diagnosis of tuberculous epididymo-orchitis was made. Consequent upon this diagnosis, the patient was referred for treatment at the local tuberculosis treatment centre.

Case report

A 44-year old civil servant presented with a history of left scrotal mass of 4 months duration and a month's history of low grade fever to the State specialist hospital, Gombe. The scrotal mass which was initially painless later became slightly painful with a discharging sinus. He was healthy looking with essentially normal systemic findings except for the urogenital system. There was a left-sided scrotal swelling measuring 10 × 6cm, painful with a discharging sinus. An initial diagnosis of epididymoorchitis was made. A swab of the discharge was taken for m/c/s and he was commenced on antibiotics. The culture yielded no growth but the pain subsided following a course of antibiotics. Few weeks later, the scrotal mass was observed to be constant in size, firm and painless. A diagnosis of testicular tumour was made. The patient had orchidectomy and post-operative condition was stable. The specimen was sent to the histopathology unit of the Laboratory department of FMC, Gombe.

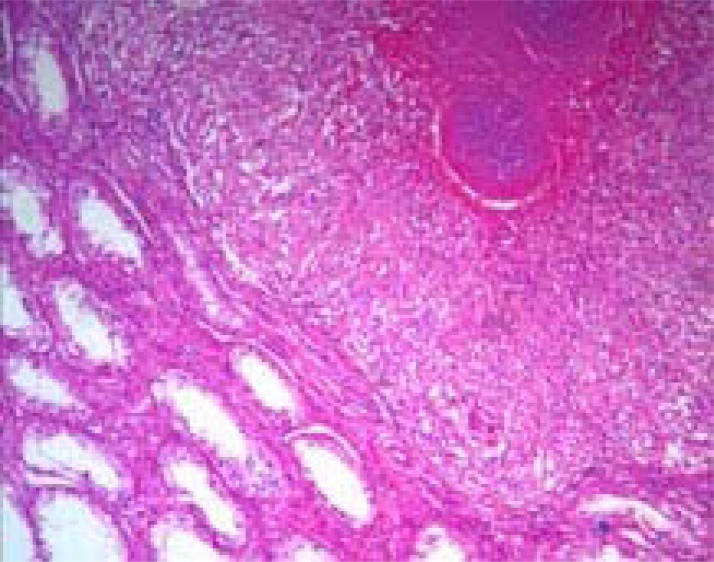

We received an irregularly shaped soft tissue mass that measured 9 × 5 × 3 cm and weighed 100g. Cut surface showed largely creamy white tissue (figure 1). Microscopy revealed testicular tissue with distorted architecture due to the presence of numerous tuberculous granulomas that has replaced most of the normal tissue (figure 2). Histopathological diagnosis of tuberculous epididymo-orchitis was made. Patient was thereafter referred to the TB treatment centre. He was commenced on a 6-month's regimen of rifampicin, izoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol but was lost to follow-up shortly after commencing treatment.

Figure 1.

Gross section of testicular mass showing white cheesy appearance

Figure 2.

Testicular tissue showing caseating granulomas replacing most of the normal tissue. Haematoxylin & Eosin × 100

Discussion

Tuberculosis is a global epidemic with more than 2 billion of the world population infected.6 Estimated 9 million new cases of TB were reported in 2007 and about 1.3 million deaths occurred among HIV-negative patients.7 The patient presented was neither evaluated for HIV infection nor fully investigated for TB of other organs in the body at the State specialist hospital where he had surgery. Even after diagnosis and commencement of antituberculosis treatment, follow-up was poor and patient eventually defaulted illustrating one of the challenges to TB treatment in Nigeria. Tuberculosis initiates granulomatous inflammation and destruction of the native tissue with consequent loss of function. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is important because presentations in patients may simulate malignant tumours with diagnostic and treatment challenges. Several publications have reported various common sites of EPTB to include lymph nodes, abdominal organs, spine and GUTB.8 It was also observed that many cases of EPTB are associated with concurrent or prior pulmonary TB.8

TB epididymo-orchitis is a common form of GUTB but when it is isolated, it may mimic testicular tumour.3 Testicular tumour is rare among blacks and requires surgical removal with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy unlike testicular TB. Reported cases with clinical diagnosis of testicular tumours that were found to be testicular tuberculosis after surgery sometimes have TB affecting other associated organs like the seminal vesicle, prostate or kidneys.2,9,

In most developing countries including sub-Saharan Africa where the burden of TB is highest, a complex intricate of poverty, overcrowding, malnutrition coupled with lack of newer diagnostic techniques have made adequate evaluation of patients prior to surgery difficult.9 In the case presented, testicular and abdominal ultrasound with CT scan, and fine needle aspiration biopsy would have provided a guide to the management. Although most of these were not available at the general hospital, a referral to a tertiary hospital would have been ideal for this patient but the cost may be prohibitive. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has been reported to enhance diagnosis of testicular TB in conjunction with USS-CT scan.5

Typical picture seen on FNAC includes epithelioid granuloma with a necrotic background and variable lymphocytic presence. Ziehl-Neelsen stain performed on alcohol-fixed slides usually confirms presence of numerous acid-fast bacilli. Microscopy and culture negativity may not necessarily rule out TB as illustrated in this case where culture of the discharge was negative. In addition to FNAC, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when available has been shown to provide rapid detection of M. tuberculosis.2,10 Treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs in FNAC or PCR confirmed GUTB case may obviate the need for surgery and limit further organ damage. It is imperative that while striking a balance between cost and treatment, patients should be thoroughly investigated as the resultant infertility/subfertility from orchidectomy may far outweigh the cost of investigation for a medically treatable condition such as tuberculosis.

References

- 1.Kapoor R, Ansari MS, Mandhani A, Gulia A. Clinical presentation and diagnostic approach in cases of genitourinary tuberculosis. Indian J Urol. 2008;24:401–405. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.42626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wise GJ, Shteynshlyuger A. An update on lower urinary tract tuberculosis. Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9:305–313. doi: 10.1007/s11934-008-0053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shenoy VP, Viswanath S, D'Souza A, Bairy I, Thomas J. Isolated tuberculous epididymoorchitis: an unusual presentation of tuberculosis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:92–94. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Ahuja A, Gupta SD. Incidence, etiopathogenesis and pathological aspects of genitourinary tuberculosis in India: A journey revisited. Indian J Urol. 2008;24:356–361. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.42618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sah SP, Bhadani PP, Regmi R, Tewari A, Raj GA. Fine needle aspiration cytology of tubercular epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:243–249. doi: 10.1159/000325949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlow B. Tuberculosis: a review and update. Radiol Technol. 2010;82:33–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanekom WA, Lawn SD, Dheda K, Whitelaw A. Tuberculosis research update. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:981–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozvaran MK, Baran R, Tor M, Dilek I, Demiryontar D, Arinc S, et al. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in non-human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in an endemic region. Ann Thorac Med. 2007;2:118–121. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.33700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orakwe JC, Okafor PI. Genitourinary tuberculosis in Nigeria; a review of thirty-one cases. Niger J Clin Pract. 2005;8:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Causse M, Ruiz P, Gutierrez-Aroca JB, Casal M. Comparison of two molecular methods for rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3065–3067. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00491-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]