Abstract

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care, based on all or part of the Acute Care for Elders (ACE) model and introduced in the acute phase of illness or injury, with that of usual care.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled and quasi-experimental trials with parallel comparison groups retrieved from multiple sources.

Setting

Acute care geriatric and nongeriatric hospital units.

Participants

Acutely ill or injured adults (N = 6,839) with an average age of 81.

Interventions

Acute geriatric unit care characterized by one or more ACE components: patient-centered care, frequent medical review, early rehabilitation, early discharge planning, prepared environment.

Measurements

Falls, pressure ulcers, delirium, functional decline at discharge from baseline 2-week prehospital and hospital admission statuses, length of hospital stay, discharge destination (home or nursing home), mortality, costs, and hospital readmissions.

Results

Acute geriatric unit care was associated with fewer falls (risk ratio (RR) = 0.51, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.29–0.88), less delirium (RR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.61–0.88), less functional decline at discharge from baseline 2-week prehospital admission status (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.78–0.97), shorter length of hospital stay (weighted mean difference (WMD) = −0.61, 95% CI = −1.16 to −0.05), fewer discharges to a nursing home (RR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.68–0.99), lower costs (WMD = −$245.80, 95% CI = −$446.23 to −$45.38), and more discharges to home (RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.10). A nonsignificant trend toward fewer pressure ulcers was observed. No differences were found in functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge, mortality, or hospital readmissions.

Conclusion

Acute geriatric unit care, based on all or part of the ACE model and introduced during the acute phase of older adults' illness or injury, improves patient- and system-level outcomes.

Keywords: ACE model, elderly, meta-analysis, function-focused interventions, acute geriatric unit

Adults aged 65 and older constitute the “core business” of hospitals.1 Although they represent 13% of the population in the United States2 and 14% of the population in Canada,3 older adults account for 43% of inpatient hospital days in the United States4 and 40% in Canada.5 This trend is likely to continue given population aging.3

During hospitalization for an acute event such as illness or injury, older adults are at risk of experiencing functional decline and iatrogenic complications, including falls, pressure ulcers, and delirium, which further contribute to functional decline.6 Hospital-acquired functional decline is associated with greater hospital expenditures, institutionalization, and mortality in older adults7 even after controlling for comorbidity and illness severity.8 Therefore, early intervention (before an acute episode is resolved) is critical because of the short length of time during which older persons can recover functional losses, resume their former lives, and avoid institutionalization.9

Dedicated geriatric units, based on a prehabilitation10 and function-focused11 model of care called Acute Care for Elders (ACE), have been designed specifically to prevent functional decline and related complications in older adults admitted to the hospital for an acute event.12,13 In response to an increasingly older and complex hospital population, some service providers have adopted the ACE model on hospital units where older adults are admitted.13 However, the overall effect of acute geriatric unit care, based on all or part of the ACE model and introduced during the acute phase of illness or injury, is unclear and unquantified.

Two systematic reviews of acute geriatric unit care based on the ACE model have been conducted,14,15 but the authors did not present results of meta-analyses, supporting the need for this current review. Three prior reviews combined data from studies conducted with individuals in the acute and subacute illness phases;14,16,17 the results have limited validity for individuals in the acute phase of an illness or injury. One meta-analysis18 imputed means for missing standard deviations for cost and length-of-stay outcomes in almost 30% of included studies,18 which may have resulted in an underestimation of the overall effect. Last, no meta-analysis of acute geriatric unit care included iatrogenic complications, which are critical indicators of quality hospital care.19

The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care, based on all or part of the ACE model components and introduced in the acute phase of illness or injury, in reducing iatrogenic complications, functional decline, length of hospital stay, poor discharge destination outcomes, mortality, costs, and hospital readmissions in older adults.

Methods

A systematic review was performed that compared acute geriatric unit care, in which all or part of the ACE model components were introduced in the acute phase of illness or injury, with usual care using the Cochrane Collaboration Protocol.20

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies included published and unpublished randomized controlled and quasi-experimental trials with parallel controls that compared acute geriatric unit care with usual care for adults aged 65 and older in the acute illness or injury phase.17 Acute geriatric unit care included at least one of the five ACE model components or principles:13,21,22 patient-centered care, defined as care activities (assessments and protocols) to prevent declines in activities of daily living (ADLs), mobility, continence, nutrition, skin integrity, mood, sleep, and cognition; frequent medical review, defined as activities to minimize the adverse effects of treatments on older adults' functioning; early rehabilitation, defined as the participation of physical or occupational therapists in daily team meetings for the purposes of initiating rehabilitation or standard provision of physical or occupational therapy; early discharge planning, defined as activities to facilitate return to the community; and prepared environment, defined as environmental modifications to facilitate physical and cognitive functioning. Usual care was defined as any care not provided on an acute geriatric unit.

Eligible studies included at least one primary (iatrogenic complications or functional decline) or secondary (length of hospital stay, discharge destination, mortality, costs, or hospital readmissions) outcome. Iatrogenic complications included falls (defined as the number of individuals who experienced ≥1 falls), pressure ulcers (defined as the number of individuals who experienced skin breakdown), or delirium (defined as the number of individuals diagnosed with ≥1 delirium episodes) during hospitalization. Functional decline was defined as loss of independence at discharge in at least one of five basic ADLs: transfers, toileting, dressing, eating, or bathing,10 as measured as the Barthel Index or the Katz ADL scale, 2 weeks before hospital admission or upon hospital admission. Length of hospital stay was defined as the total number of days in the hospital or as the time between study admission and discharge if total number of days in the hospital was not provided. Discharge destination included discharge to home (defined as own home or with family) or nursing home (defined as nursing home, sheltered living, or hostel). Mortality refers to number of deaths during hospitalization. Costs were defined as total hospital costs associated with care for the duration of hospital stay. Cost data were standardized to U.S. dollars for a common price year of 2000, the last study year with published cost data. Hospital readmissions refer to the number of individuals readmitted one or more times to an acute care hospital within 1 or 3 months after discharge from the study hospital.

Studies unavailable in English or French, involving individuals undergoing elective surgical procedures or receiving palliative care, including social admissions, or with historical control groups were ineligible.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

An information specialist conducted the literature search with input from team members with expertise in the clinical area to identify keywords reflective of the ACE model (Appendix S1 of the electronic supplementary material). Electronic databases searched were as follows: Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews consisting of the Cochrane Library, DARE, HTA, NHSEED and ACP; MEDLINE; EMBASE; CINAHL; Proquest Dissertations and Theses; PubMed; Web of Science; SciSearch; PEDro; Sigma Theta Tau International's registry of nursing research; Joanna Briggs Institute; CRISP; and OT Seeker. Internet search engines included Google, Yahoo, Scirus, Healia, and HON. Hand-searching was conducted in the Gerontologist, Age and Ageing, JAMA, and bibliographies of all included articles and previous systematic reviews.

Two reviewers independently screened abstracts of the retrieved citations for potential inclusion. Disagreements about eligibility were resolved by consensus between two reviewers. Where consensus could not be reached, a third team member independently reviewed the abstract and determined final inclusion. When necessary, the complete article was reviewed to determine eligibility.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted relevant data from each included article and entered the data into a standardized data extraction form. Information categories included study design, participants, ACE components, healthcare providers, occasions of measurement, and outcomes. Two reviewers independently assessed each study's risk of bias using six defined domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective reporting; and other sources of bias.20

Study authors were contacted if additional data were required. Disagreements on data extraction and risk of bias assessments were resolved by consensus with assistance of a third team member.

Data Analysis

When sufficient data were available and studies were comparable in terms of outcomes, meta-analyses were performed using review manager software.20 When data were neither retrievable from study authors nor derivable from available data, values were not assumed for the purposes of meta-analyses. In studies in which per-protocol and intention-to-treat data were reported, the latter were analyzed. Continuous and dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using a random-effects model to calculate weighted mean differences (WMDs) and risk ratios (RRs), respectively, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P < .05 was considered statistically significant for an overall effect. P < .10 was considered statistically significant for heterogeneity.23 Degree of heterogeneity is reported according to the I2 statistic, which refers to the degree of variation between studies.20 Because of the potential for clinical heterogeneity of study populations and ACE components and the associated risk of a false-negative I2 statistic,24 the CIs of individual studies contained in the forest plots were also examined.20 In situations in which heterogeneity was statistically significant or was not statistically significant but there was minimal overlap of the CIs, sensitivity analyses were performed whereby studies were systematically removed from meta-analyses to determine robustness of findings. Decisions for removing studies were based on their potential sources of variability; studies conducted on surgical units were removed first, followed by studies conducted on medical–surgical units, and then studies that did not implement all five ACE components, beginning with studies that implemented the fewest components.

Results

Description of Studies

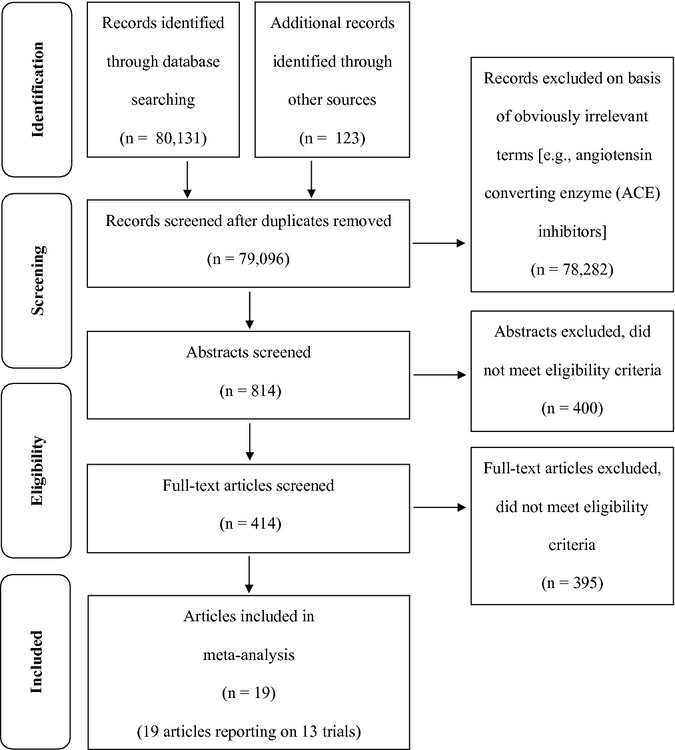

Searches of all sources yielded 79,096 citations, of which 19 studies21,22,25–41 reporting on 13 trials met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Characteristics of the 13 trials21,22,25,26,28–31,35,38–41 are provided in Appendix S2 Table S1 of the electronic supplementary material.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.49

Six thousand eight hundred thirty-nine participants were included in this review. The average study participant was aged 81, female (61.8%), and admitted with an acute medical illness (81.3%),21,22,25,26,30,35,38–41 fracture (6.9%),26,29,31 unspecified acute or critical illness (11.8%),26,28,38 or other morbidity.21,22,25,29–31,35,38–40 Sixty-two percent of the studies restricted eligibility to individuals admitted through hospital emergency departments.21,22,25,29–31,40,41

Acute geriatric unit care most often included patient-centered care,21,22,25,26,28–31,35,38–41 followed by frequent medical review,21,22,25,28,31,35,39–41 early rehabilitation,21,22,25,28,31,40,41 early discharge planning,21,22,25,26,35,40,41 and prepared environment.21,22,35,39,41 Acute geriatric unit teams comprised predominantly physicians and nurses,21,22,25,26,28–31,35,38–41 followed by physical therapists,21,22,25,26,28–31,35,40,41 social workers,21,22,26,28,30,31,35,38,40,41 geriatricians,21,25,29–31,38,39,41 and occupational therapists.21,22,25,26,30,31,40 Interdisciplinary teams met regularly to plan patient care.21,22,26,28,29,31,35,39–41

Usual care consisted of standard nursing and medical care that was neither functionally focused21,22 nor interdisciplinary team directed.21,22,25,31,41 Usual care was provided on medical,21,22,25,30,35,39–41 medical–surgical,26,28,30 or surgical orthopedic29,31 units.

Risk of Bias

Selection bias resulting from inadequate sequence generation was low in seven of the 13 studies.21,22,25,26,30,31,41 Three studies that used randomization provided insufficient information to draw conclusions in this domain28,35 or were considered not to have been properly randomized.29 Three studies were determined to have high risk of selection bias because randomization was not performed.38–40

Risk of selection bias resulting from inadequate allocation concealment was low in six of the 13 studies.21,22,25,26,31,41 Allocation was not concealed in one study, resulting in a high risk assessment.30 In all other studies, risk of bias was unclear because allocation information was not provided.28,29,35,38–40

Risk of performance bias related to double blinding (participants and personnel) was unclear because seven studies did not provide this information.22,28,29,35,38–40 Three studies were double blinded and considered to have low risk of performance bias,21,26,31 whereas three studies were not double blinded and were considered to have high risk of performance bias.25,30,41

Risk of detection bias related to blinding of outcome assessors was unclear because 11 studies did not provide this information.21,22,25,26,28–30,35,38–40 One study was considered high risk because outcomes assessors were blinded to only one of several outcomes.41 Only one study reported that outcome assessors were blinded and was considered to have low risk of bias.31

Risk of attrition bias related to completeness of outcome data was low in six studies22,28–31,41 and unclear in one.38 Six studies were considered to have high risk of bias because of postrandomization exclusions25,39 or attrition.21,26,35,40

Risk of reporting bias due to selective reporting was low22,28,31,35,41 or unclear.25,29,30,38–40 One study26 was considered to have high risk of reporting bias because its length-of-stay and cost data were missing. None of the 13 studies appeared to be at risk of other sources of bias that were not addressed in prior domains.

Effectiveness of Acute Geriatric Unit Care

Eleven meta-analyses were performed. Unpublished data were obtained from study authors to perform meta-analyses on functional decline between baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge,39 length of hospital stay,27,29,39,41 mortality,35 and costs.21,41 Four sensitivity analyses were conducted for functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge, length of hospital stay, discharge to nursing home, and costs.

Iatrogenic Complications

Falls and pressure ulcers were reported in the same two studies26,31 resulting in two meta-analyses. Acute geriatric unit care was associated with significantly fewer falls (RR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.29–0.88; P = .02) and nonsignificantly fewer pressure ulcers (RR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.23–1.04; P = .06) in acutely ill or injured older adults than usual care.

Delirium was reported in three studies.25,31,39 Meta-analysis of these three studies showed that acute geriatric unit care was associated with significantly less occurrence of delirium than usual care in acutely ill or injured older adults (RR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.61–0.88; P = .001).

Functional Decline

Functional decline between baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge was reported in six studies.21,22,31,39–41 Meta-analysis of these six studies indicated that individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care were 13% significantly less likely to experience functional decline between their baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge than those receiving usual care (RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.78–0.97; P = .01).

Functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge was reported in four studies.21,22,40,41 Meta-analysis of these four studies showed that, compared to usual care, individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care experienced no significant difference in risk of functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge (RR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.64–1.08; P = .16). Significant statistical heterogeneity was observed for this comparison. With removal of one outlier study40 during sensitivity analysis, statistical heterogeneity was resolved, although the effect remained nonsignificant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of Meta-Analyses

| Outcome | Individual Studies Included in Meta-Analysis | N | WMD (95% CI) or RR (95% CI)a | Test for Overall Effect, Z (P-Value) | I2 Statistic (P-Value) for Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iatrogenic complications | |||||

| Falls | Collard et al.26 Olofsson31 | 749 | 0.51 (0.29–0.88) | 2.41 (.02) | 0% (.55) |

| Pressure ulcers | Collard et al.26 Olofsson31 | 749 | 0.49 (0.23–1.04) | 1.87 (.06) | 25% (.26) |

| Delirium | Asplund et al.25 Olofsson31 Vidan et al.39 | 1,154 | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) | 3.29 (<.001) | 0% (.44) |

| Functional decline at discharge from baseline | |||||

| 2-week prehospital admission status | Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Landefeld et al.22 Olofsson31 Vidan et al.39 Zelada et al.40 | 4,485 | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 2.55 (.01) | 37% (.16) |

| Hospital admission status | Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Landefeld et al.22 Zelada et al.40 | 3,860 | 0.83 (0.64–1.08) | 1.41 (.16) | 68% (.03) |

| Outlier removed | Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Landefeld et al.22 | 3,717 | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 0.83 (.41) | 52% (.12) |

| Length of hospital stay, daysc | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Covinsky et al.27, b Fretwell et al.28 González-Montalvo et al.29 Harris et al.30 Olofsson31 Stewart et al.38 Vidan et al.39 Zelada et al.40 | 6,098 | –1.28 (–2.33 to –0.22) | 2.37 (.02) | 87% (<.001) |

| Outliers removed | Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Covinsky et al.27, b Zelada et al.40 | 3,956 | –0.61 (–1.16 to –0.05) | 2.12 (.03) | 45% (.14) |

| Discharge destination | |||||

| Home | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Collard et al.26 Fretwell et al.28 González-Montalvo et al.29 Harris et al.30 Landefeld et al.22 Olofsson31 Somme et al.35 | 4,315 | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 2.69 (.01) | 0% (.54) |

| Nursing home | Asplund et al.25 Collard et al.26 Counsell et al.21 Fretwell et al.28 González-Montalvo et al.29 Harris et al.30 | 3,378 | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) | 0.48 (.63) | 50% (.06) |

| Outliers removed | Asplund et al.25 Counsell et al.21 Harris et al.30 | 2,040 | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 2.10 (.04) | 0% (.57) |

| Mortality | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Collard et al.26 Counsell et al.21 Fretwell et al.28 González-Montalvo et al.29 Harris et al.30 Landefeld et al.22 Olofsson31 Somme et al.35 Vidan et al.39 | 6,612 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 0.13 (.90) | 11% (.33) |

| Costs (U.S. dollars standardized to 2000)c, d | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Covinsky et al.27, b Stewart et al.38 | 4,287 | –431.37 (–933.15–70.41) | 1.68 (.09) | 44% (.13) |

| Outlier removed | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Covinsky et al.27 | 4,226 | –245.80 (–446.23 to –45.38) | 2.40 (.02) | 0% (.66) |

| Hospital readmissions | Asplund et al.25 Barnes et al.41 Counsell et al.21 Landefeld et al.22 Olofsson31 | 3,983 | 1.05 (0.92–1.18) | 0.69 (.49) | 0% (.55) |

Risk ratios (RRs) reported for all meta-analyses of all outcomes except cost and length of hospital stay, for which weighted mean difference (WMDs) are reported.

Covinsky et al. 27 and Landefeld 199522 refer to the same trial. Costs and length of hospital stay data extracted from Covinsky et al. 27

Length of hospital stay and cost data from Collard and colleagues26 were excluded from meta-analyses; the reported standard errors were deemed erroneous because they contradicted their associated significance levels.50

Costs were measured according to actual costs captured in hospital financial or accounting systems or charge data, which approximates costs of care using diagnostic information about each participant. When individuals were recruited into a study that covered a number of years, the cost year was presumed to be the middle year. When a year of recruitment was unavailable, the cost year was estimated to be 4 years before the publication date. Cost conversions performed June 22, 2012, using a Web-based cost converter endorsed by the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group.20

CI = confidence interval.

Length of Hospital Stay

Length of hospital stay was reported in 12 studies,21,22,25,26,28–31,38–41 with complete data in 11.21,22,25,28–31,38–41 Meta-analysis of these 11 studies showed that individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care experienced a significantly shorter length of hospital stay than those receiving usual care (WMD = −1.28, 95% CI = −2.33 to −0.22; P = .02). Significant statistical heterogeneity was observed between studies for this comparison. After removal of seven outlier studies25,28–31,38,39 during sensitivity analysis, the significant effect remained (WMD = −0.61, 95% CI = −1.16 to −0.05; P = .03), and statistical heterogeneity resolved (Table 1).

Discharge Destination

Nine studies reported whether participants were discharged home.22,25,26,28–31,35,41 Meta-analysis of these nine studies identified that individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care were 1.05 times more likely to be discharged home than those receiving usual care (RR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.10; P = .01).

Six studies reported whether participants were discharged to a nursing home.21,25,26,28–30 Meta-analysis of these six studies identified no significant effect, although significant statistical heterogeneity was observed between studies for this comparison (Table 1). With the removal of three outlier studies26,28,29 that resolved the heterogeneity, a meta-analysis identified that individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care were significantly less likely than those receiving usual care to be discharged to a nursing home (RR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.68–0.99; P = .04).

Mortality

Mortality was reported in 11 studies.21,22,25,26,28–31,35,39,41 Meta-analysis of these 11 studies identified no significant difference in mortality during hospital stay between individuals receiving acute geriatric and usual care (Table 1).

Costs

Costs were reported in six studies,21,25–27,38,41 with complete data in five studies.21,25,27,38,41 Meta-analysis of these five studies showed that the costs of acute geriatric unit care were nonsignificantly less than the costs of usual care (WMD = −$431.37, 95% CI = −$933.15–$70.41; P = .09), although clinical heterogeneity was observed between studies for this comparison, as indicated by the minimal overlap of one study's CIs38 with those of the other studies (Appendix S3 of the electronic supplementary material). Heterogeneity was resolved with removal of one outlier study38 during sensitivity analysis; the results demonstrated that the costs of acute geriatric unit care were significantly less than those of usual care (WMD = −$245.80, 95% CI = −$446.23 to −$45.38; P = .02).

Hospital Readmissions

Two studies reported on hospital readmissions within 1 month of discharge,21,31 and three reported on hospital readmissions within 3 months of discharge.22,25,41 Meta-analysis of these five studies identified no significant difference in hospital readmissions within 1 or 3 months of discharge between individuals receiving acute geriatric unit care and those of individuals receiving usual care (Table 1).

Post Hoc Analyses

Post hoc subgroup meta-analyses were performed in the three studies that examined the effect of the full ACE model on the study outcomes. Results remained significant (length of hospital stay)21,22,41 or nonsignificant (functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge, mortality, and hospital readmissions)21,22,41 or were inconclusive because of heterogeneity (discharge home)22,41 or no longer significant (functional decline between baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge21,22,41 and costs21,27,41). The last may have been because of low power resulting in a Type I error.

Discussion

This is the first combined systematic review and meta-analysis of acute geriatric unit care based on all or part of the ACE model components and the first to examine iatrogenic complications and functional decline between baseline hospital admission status and discharge. Results from meta-analyses demonstrate that acute geriatric unit care including one or more ACE components and introduced during the acute illness or injury phase has significant beneficial effects over usual care in reducing falls, delirium, functional decline between baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge, length of hospital stay, discharge to a nursing home, and costs and in increasing discharges to home. In addition, a nonsignificant trend of finding fewer pressure ulcers was observed. Given the demographic and health characteristics of the average study participant, these findings are mainly applicable to octogenarians admitted through the emergency department with acute illnesses or injuries and other morbidities.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The findings have relevance for clinicians, hospital administrators, policy-makers, and funders. By implementing all or part of the ACE model components during older adults' acute illness or injury phase, clinicians may anticipate small to moderate beneficial effects on the outcomes found to be significant in the meta-analyses. Although further research is needed, clinicians may also anticipate fewer pressure ulcers. Patient-centered care, frequent medical review, early rehabilitation, and early discharge planning were provided in more than half the studies and may represent the optimal ACE components for positive outcome achievement. Interdisciplinary team work was also a unique characteristic of acute geriatric unit care and may be important for clinicians to consider in their practice.

The findings are applicable to the care of acutely ill and injured older adults on medical, surgical, and medical–surgical units, and they address concerns about limited applicability and benefit of ACE to nonmedical patient groups and units.42 Older adults with acute injuries typically have comorbidities that precipitated the injury and complicate its management and therefore benefit from a function-focused prehabilitation approach.

Hospital administrators may anticipate cost savings of approximately $246 per hospital stay in U.S. dollars standardized to 2000 and more than a half-day shorter hospital stay than with usual care. Older adults account for 50% of Canadian43 and 45% of U.S.44 hospital expenditures. With projected increases in age demographics in both countries,3 this cost difference may represent a significant future source of financial saving to both healthcare systems. This finding addresses cost-ineffectiveness12 and cost-prohibitiveness45 barriers to adopting the ACE model.

By establishing ACE as the preferred model of care, policy-makers can play an influential role in its adoption and in the improvement of patient- and system-level outcomes. By changing reimbursement or charge rates and by establishing targets for cost and resource efficiency for older people's care, funders can create the external and substantive structural incentives needed to move ACE into the “mainstream of hospital care.”46

Comparison with Previous Research

The findings of the current study are similar to those of an earlier meta-analysis of older adults with medical disorders18 that found that acute geriatric unit care, which may or may not have included the ACE components, had significant effects on preventing functional decline between baseline 2-week prehospital admission status and discharge, increasing discharges home, and reducing costs and nonsignificant effects on mortality and hospital readmissions. However, in contrast to the earlier meta-analysis, which found nonsignificant or inconclusive effects on length of hospital stay or discharges to a nursing home,18 the current meta-analysis identified significant reductions in length of hospital stay and discharges to a nursing home after acute geriatric unit care in which ACE components were provided in varying degrees. These findings concur with a prior narrative analysis comparing ACE with usual care units.15

This review included six new randomized31,35,41 and quasi-experimental29,39,40 trials, which resulted in larger sample sizes of many of the meta-analyses than in prior research. CIs were also more precise for most outcomes than were those of prior meta-analyses.18

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This review had little missing data because six study authors21,27,29,35,39,41 provided unpublished data, minimizing publication bias. The review included a small number of studies with limited information regarding study methods, which restricted the ability to draw conclusions regarding level of bias in several domains. Although randomization was used in most studies, six21,25,26,35,39,40 had postrandomization exclusions or did not report related information, which may have contributed to an overestimation of effect sizes. Sample sizes in the meta-analyses on iatrogenic complications were modest, which may have influenced the imprecision of the estimates.

Although this review included a diverse group of individuals admitted to medical, medical-surgical, or surgical units, heterogeneity was low in the majority of meta-analyses, supporting validity of the results. It was not possible to perform subgroup meta-analyses (medical vs surgical) because three studies did not report results separately for medical and surgical patients26,28,38 and because of the potential for bias with small and uneven distribution of groups.20

Implications for Future Research

This review highlights the limited number of studies examining the effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care based on all or part of the ACE model components on outcomes of importance to older adults and service providers, specifically iatrogenic complications, costs, and hospital readmissions. With increasing concerns about safe and fiscally responsible care that does not result in hospital readmissions,47 future research should examine the effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care on these outcomes.

Future research should explore the effectiveness of the ACE components with surgical patients. As ACE continues to be adopted and tested in the care of older surgical patients, future researchers may conduct subgroup analyses to compare its effectiveness in medical patients with its effectiveness in surgical patients.

Most studies restricted entry to individuals admitted through the emergency department. Given the importance of community services,48 future trials should include older adults admitted to the hospital through avenues other than the emergency department. Future trials should also provide more-detailed descriptions of the methods used to facilitate assessment of the risk of bias and interpretation of results.

A prior meta-analysis18 examining the effectiveness of admission to acute geriatric units excluded studies that limited admission to acutely injured individuals but included studies with mixed samples of acutely ill and injured individuals. Inclusion of both types of studies in the current analysis did not lead to any more heterogeneity than previously reported, supporting the inclusion of acutely ill and injured older individuals in future meta-analyses.

Last, this review illustrates that few trials have examined the effectiveness of the full ACE model. Future updates of this review may enable new studies that explore the full ACE model to be incorporated into these subgroup meta-analyses, which will help to more accurately determine the effectiveness of the full ACE model.

Acknowledgments

Oral and poster presentations based in part on the study findings were given at the annual conferences of the Canadian Association on Gerontology, October 22, 2011, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research, May 29, 2012, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Hugh McCague, statistician, Institute of Social Research, York University, for his statistical advice; decision-making partners Ms. Tiziana Rivera, Chief Practice Officer, York Central Hospital, and Dr. Mary Ferguson-Paré, former Vice-President of Professional Affairs and Chief Nurse Executive, University Health Network, for their advice on the grant which supported this study; and Drs. Counsell, Covinsky, González-Montalvo, Landefeld, Somme, and Vidan for generously providing us with their data.

Conflict of Interest: Financial support provided by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant KRS-94307 and Faculty of Health Minor Research Grant, York University. Mary Fox was supported by an Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Career Scientist Award, Kelly O'Brien by a CIHR Fellowship, Dina Brooks by a Canada Research Chair, and Deborah Tregunno by an Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Senior Nurse Research Award while conducting this study.

The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Study concept: Fox. Study design: Fox, Maimets, O'Brien, Brooks, and Tregunno. Literature searching and initial records screening: Fox, Persaud, and Maimets. Abstract and article screening for eligibility and risk of bias assessments: Fox, Persaud, O'Brien, Brooks, and Tregunno. Cost analysis and write-up: Schraa. Data extraction and interpretation: Fox, Persaud, O'Brien, Brooks, and Tregunno. Data analysis: Fox, Persaud, and O'Brien. Manuscript preparation: Fox. Critical revision of manuscript: Persaud, Maimets, O'Brien, Brooks, and Tregunno.

Sponsor's Role: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix S1. Search strategy for MEDLINE (OVID).

Appendix S2. Descriptive characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Appendix S3. Forest plots for all meta-analysis, including sensitivity analyses.

References

- 1.Mezey M, Boltz M, Esterson J, et al. Evolving models of geriatric nursing care. Geriatr Nur. 2005;26:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving the health of older Americans: A Centers for Disease Control (CDC) priority. Chronic Dis Notes Rep. 2007;18:1–2. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Canada. Canada's population estimates: Age and sex [on-line]. Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/110928/dq110928a-eng.htm Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 4.Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, et al. National hospital discharge survey: 2007 summary. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2010 [on-line]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr029.pdf Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 5.Health Care in Canada. A focus on seniors and aging. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information; 2011. 2011. Available at https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/HCIC_2011_seniors_report_en.pdf Accessed July 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh KA, Bruza JM. Review: Hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Longterm Care. 2007;15:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: Increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown CJ, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson M, Holthaus D, Harvell J, et al. Medicare post-acute care: Quality measurement final report [on-line]. Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/mpacqm.htm#chapIV Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 10.Palmer RM, Counsell SR, Landefeld SC. Acute care for elders units: Practical considerations for optimizing health outcomes. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2003;11:507–517. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: Lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amador LF, Reed D, Lehman CA. The acute care for elders unit: Taking the rehabilitation model into the hospital setting. Rehabil Nurs. 2007;32:126–132. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2007.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong RYM, Shaw M, Acton C, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to optimize health services in a specialized acute care for elders unit. Geriat Today. 2003;6:177–186. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen K, Turner T. Effectiveness of acute care of the elderly (ACE) units. South Health. 2008:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed NN, Pearce SE. Acute care for the elderly: A literature review. Popul Health Manag. 2010;13:219–225. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker G, Bhakta P, Katbamna S, et al. Best place of care for older people after acute and during subacute illness: A systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;53:176–189. doi: 10.1177/135581960000500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day P, Rasmussen P. What is the evidence for the effectiveness of specialized geriatric services in acute, post-acute and sub-acute settings? A critical appraisal of the literature. N Z Health Technol Assess. 2004;7:1–169. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baztán JJ, Suárez-García, Lóez-Arrieta J, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: Meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Permpongkosol S. Iatrogenic disease in the elderly: Risk factors, consequences, and prevention. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:77–85. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 [on-line]. Available at http://www.cochrane-handbook.org Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 21.Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care of hospitalized older patients: A randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1338–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau J, Ioannidis JPA, Schmid CH. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:820–826. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West SL, Gartlehner G, Mansfield AJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness review methods: Clinical heterogeneity. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2010 [on-line]. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53317/ Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 25.Asplund K, Gustafson Y, Jacobsson C, et al. Geriatric-based versus general wards for older acute medical patients: A randomized comparison of outcomes and use of resources. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1381–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collard AF, Bachman SS, Beatrice DF. Acute care delivery for the geriatric patient: An innovative approach. Qual Rev Bull. 1985;11:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Covinsky KE, King JT, Quinn LM, et al. Do acute care for elders units increased hospital costs? A cost analysis using the hospital perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fretwell MD, Raymond PM, McGarvey ST, et al. The Senior Care Study. A controlled trial of a consultative/unit-based geriatric assessment program in acute care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1073–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Alarcon T, Mauleon JL, et al. The orthogeriatric unit for acute patients: A new model of care that improves efficiency in the management of patients with hip fracture. Hip Int. 2010;20:229–235. doi: 10.1177/112070001002000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris RD, Henschke PJ, Popplewell PY, et al. A randomised study of outcomes in a defined group of acutely ill elderly patients managed in a geriatric assessment unit or a general medical unit. Aust NZ J Med. 1991;21:230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1991.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olofsson B. Old people with femoral neck fracture: Delirium, malnutrition and surgical methods—an intervention program. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 2007. [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Lundstrom M, et al. Malnutrition in hip fracture patients: An intervention study. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:2027–2038. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundstrom M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: A randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:178–186. doi: 10.1007/BF03324687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owens NJ, Sherburne NJ, Silliman RA, et al. The Senior Care Study. The optimal use of medications in acutely ill older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1082–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somme D, Andrieux N, Guerot E, et al. Loss of autonomy among elderly patients after a stay in a medical intensive care unit (ICU): A randomized study of the benefit of transfer to a geriatric ward. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:e36–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Nyberg L, et al. Improved performance in activities of daily living and mobility after a multidisciplinary postoperative rehabilitation in older people with femoral neck fracture: A randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow up. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:232–238. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Lundstrom M, et al. A multidisciplinary, multifactorial intervention program reduces postoperative falls and injuries after neck fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart M, Suchak N, Scheve A, et al. The impact of a geriatrics evaluation and management unit compared to standard care in a community teaching hospital. Md Med J. 1999;48:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidan MT, Sanchez E, Alonso M, et al. An intervention integrated into daily clinical practice reduces the incidence of delirium during hospitalization in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2029–2036. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zelada MA, Salinas R, Baztan J. Reduction of functional deterioration during hospitalization in an acute geriatric unit. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;48:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnes DE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Acute Care For Elders units produced shorter hospital stays at lower cost while maintaining patients' functional status. Health Aff. 2012;31:1227–1236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malone ML, Vollbrecht M, Stephenson J, et al. Acute Care for Elders (ACE) tracker and e-Geriatrician: Methods to disseminate ACE concepts to hospitals with no geriatricians on staff. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2011. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2011 [on-line]. Available at https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/nhex_trends_report_2011_en.pdf Accessed July 15, 2012.

- 44.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide emergency department sample [on-line]. Available at http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp Accessed July 15, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Jr, et al. The Hospital Elder Life Program: A model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Counsell SR, Holder C, Liebenauer LL, et al. The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) Manual: Meeting the Challenge of Providing Quality and Cost-Effective Hospital Care to Older Adults. Akron, OH: Summa Health System; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benbassat J, Taragin M. Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1074–1081. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCusker J, Roberge D, Vadeboncoeur A, et al. Safety of discharge of seniors from the emergency department to the community. Healthc Q. 2009;12:24–32. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e100009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Morton NA, Keating JL, Jeffs K. Exercise for acutely hospitalised older medical patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005955.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.