Abstract

Rules for polyamide DNA recognition have proved invaluable for the design of sequence-selective DNA-binding agents in cell-free systems. However, these rules are not fully transferrable to predicting activity in cells, tissues or animals, and additional refinements to our understanding of DNA recognition would help biomedical studies. Similar complexities are encountered when using internal β-alanines as polyamide building blocks in place of N-methyl pyrrole; β-alanines were introduced in polyamide designs to maintain good hydrogen bonding registry with the target DNA, especially for long polyamides or those with several GC bp (P.B. Dervan, A.R. Urbach, Essays Contemp. Chem. (2001) 327–339). Thus, to clarify important subtleties of molecular recognition, we studied the effects of replacing a single pyrrole with β-alanine in 8-ring polyamides designed against the Ets-1 transcription factor. Replacement of a single internal N-methylpyrrole with β-alanine to generate a β/Im pairing in two 8-ring polyamides causes a decrease in DNA binding affinity by two orders of magnitude and decreases DNA binding selectivity, contrary to expectations based on the literature. Measurements were made by fluorescence spectroscopy, quantitative DNA footprinting and surface plasmon resonance, with these vastly different techniques showing excellent agreement. Furthermore, results were validated for a range of DNA substrates from small hairpins to long dsDNA sequences. Docking studies helped show that β-alanine does not make efficient hydrophobic contacts with the rest of the polyamide or nearby DNA, in contrast to pyrrole. These results help refine design principles and expectations for polyamide-DNA recognition.

Keywords: Polyamide, DNA, fluorescence spectroscopy, surface plasmon resonance, footprinting, capillary electrophoresis

1. INTRODUCTION

N-methylpyrrole and -imidazole based polyamides (PA) are being used with increasing frequency in fundamental and applied biomedical research programs [1–5]. Although the field owes much to work on Distamycin A and other lexitropsins or their analogs [6], most of the recent improvements in polyamide utility derive from the DNA recognition rules developed by Dervan [7]. These rules in principle allow one to build a polyamide to recognize a DNA sequence of interest, for example to influence transcription factor-DNA binding and control gene expression [8–10]. Dervan and Sugiyama have also published extensively on refinements to the understanding of polyamide-DNA binding, for example looking at the details of preferred and less-favored DNA-polyamide interactions and orientations [11–15]. These refinements indicate the importance of DNA sequence context and structural details of the polyamides for obtaining maximal DNA-PA binding strength.

Even with this extensive knowledge at hand and other important additions to the field [16–22], there is much that is unknown about PA design and modes of PA action in living cells. Our recent work has focused on the polyamide-based process called promoter scanning [23]: the method can identify hotspots for DNA-PA interactions that lead to improved control of gene expression. If these hotspots are near each other, it is tempting to construct larger, more specific PA molecules from the smaller active molecules identified in the promoter scanning process. This extension would take advantage of improved DNA binding strength and selectivity that can be found with larger polyamides. This approach is particularly relevant in light of recent reports that PAs over a wide range in size (400–4,000) can be biologically effective [5, 16].

To capture the activity of PA1 in more selective molecules, we previously increased PA length, adding β-alanine (β) springs every 4–5 heterocycles to keep good registry between the hydrogen bonding groups of DNA and polyamides [24], keeping the lessons of Im/G alignment in mind [26]. In a promoter scanning study to control gene expression of COX-2, we used PA1 (Figure 1) in combination with other PA sequences. We observed a complete reversal in COX-2 expression, depending on which other polyamides with which PA1 was combined [25]. However, activity of the larger molecules did not follow trends observed with the shorter PA from which they were derived [5], and the role of β appeared to be more complex than anticipated.

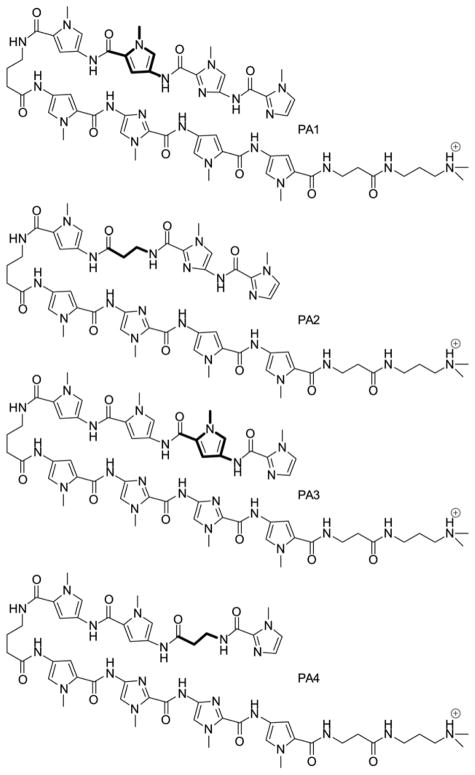

Figure 1. Structures of compounds PA1–PA4.

They are shown as monocations for clarity; they are isolated as tetracations. Bold bonds indicate the Py and β pairs compared in this study.

In order to better understand the incorporation of β in the construction of longer, more selective PAs based on PA1, we have used the PA1 framework to carry out the present biophysical study of the role of β/Im pairs vs. Py/Im pairs for DNA base pair recognition and binding. The literature provides systematic studies of β/β pairs vs. Py/Py pairs [24, 26], but not as much quantitative information is available on any changes to DNA binding that might occur by replacing a single Py residue with β. We report that, in contrast to the manner in which β helps maintain tight and selective DNA binding for some PA designs, especially when used as β/β pairs for G-rich targets, β/Im pairs can greatly decrease the binding affinity and specificity of PA molecules for DNA.

In order to validate our findings, we used orthogonal assay methods for measuring DNA binding thermodynamics and kinetics, including a fluorescence assay [27], BIAcore using biotin-labeled DNA hairpins [28–30], and quantitative footprinting [31]. To test the generality of our results, we studied a variety of DNA substrates from hairpins with 10 or 20 bp of duplex DNA derived from the COX-2 promoter to a linear, 120-mer dsDNA with one PA binding site and a 524-mer dsDNA with multiple cognate and off-target PA binding sites. Quantitative footprinting was done using fluorescent labels and capillary electrophoresis (CE) [32] rather than more traditional radiolabeling and PAGE methods. The unusual breadth of techniques in one study provides valuable perspective on the validities of various methods.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Synthesis

Polyamides were prepared by solid phase synthesis using Boc methodology [33] and were characterized by HPLC/MS (ESI+, Figures S1 – S3), 1H NMR, high resolution mass spectrometry (ESI+ MSn) and combustion analysis (C, H, N, or C, H, N, F; see supporting information). Of note, isolation by RP-HPLC using mobile phases containing 0.1%TFA led to isolated material with all basic nitrogens protonated, including imidazole; this contrasts with a previous report that used similar isolation procedures but indicated that imidazole groups were not protonated.

2.2. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Changes in fluorescence intensity of a TAMRA-labeled, hairpin-forming oligonucleotide as a function of PA concentration were used to quantitate DNA binding [27]. 5′-CCT GGA GAG GAA GCC AAG TGT TTT CAC TTG GCT TCC TCT CCA GG-3′ was purchased from IDT HPLC pure (Coralville, IA) either unlabeled or labeled with T-TAMRA at either T34 or T37 as noted by the underlined T positions in the above sequence and as shown by asterisks in Figure 2. Using a Centricon unit, the DNA was rinsed twice with Milli-Q water, subsequently annealed from boiling water, quantitated using vendor extinction coefficient, and either aliquoted, lyophilized and stored at −20 °C or used directly.

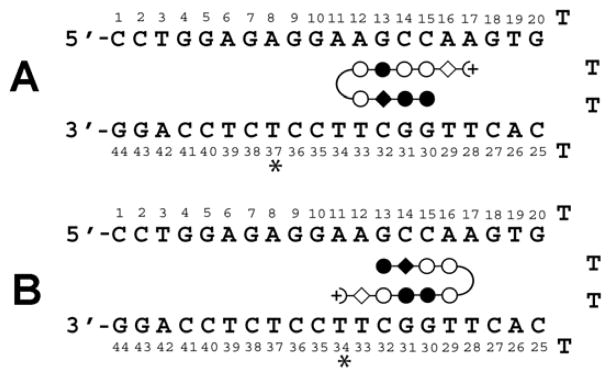

Figure 2. Map of Predicted Polyamide-DNA Interactions.

(A) PA1/2 and (B) PA3/PA4 bound to hairpin DNA. Open circle: Py; filled circle: Im; open diamond: β; filled diamond: Py (PA1, PA3) or β (PA2, PA4); (+: Dp; curved line: γ;*: position of TAMRA dye when used. A 5′-Biotin conjugate of the DNA without dye labels was used for SPR.

The experiments were performed using quartz cuvettes at 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, 25 °C on a Fluorolog-3 (SPEX) spec trofluorimeter. All samples were stirred continuously. TAMRA-labeled oligonucleotides were excited at 559 nm and the resulting emission observed through a monochromator set at 580 nm or a 592 nm bandpass filter (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ). Intensity values were obtained in triplicate and averaged and then normalized to fraction of bound DNA and then plotted against PA concentration. Resulting data were fit to equation Eq. 1:

| (Eq. 1) |

where θ is fraction of bound duplex, [L] is the total concentration of PA, nH is the Hill is the association constant. Kd values coefficient (either fixed at 1 or floated), and Ka represent an average of at least three separate experiments.

2.3. Competition Fluorescence Binding Assay

Aliquots of unlabeled DNA hairpin PA were added to a solution of fluorescent DNA-PA complex at a concentration 10-fold above the Kd. The resulting data were normalized and fit to a mathematical model describing both the labeled PA-DNA equilibrium (known Kd) and the unlabeled PA-DNA equilibrium (unknown Kd) using Scientist software (MicroMath, St. Louis, MO) as previously described [27].

2.4. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Biosensor-SPR experiments were conducted with a BIAcore T100 or T200 instrument using similar procedures to those previously described [28, 30]. 5′-Biotin labeled DNA hairpins were immobilized on streptavidin-linked sensor chips via non-covalent capture. The tight affinity between biotin and streptavidin yields a highly stable surface over time, allowing for regeneration of DNA surfaces with relatively harsh conditions. Immobilization in each flow cell is performed independently in a separate cycle, so that different DNAs can be used in different flow cells. After washing the chip with 1 M NaCl/50 mM NaOH and buffer to remove unlinked streptavidin, a 50 nM solution of each DNA sequence was injected over a streptavidin derivatized flow cell until ~400 resonance units (RU) of the long DNA (complete) sequence (as shown in Figure 2) were immobilized and ~250 RU of shorter cognate and noncognate sequences were immobilized.

Three flow cells contained DNA and one flow cell was left blank as a reference. For binding studies PA1–4 were diluted to different concentrations in degassed and filtered HEPES buffer (0.01 M HEPES and 0.001 M EDTA, 0.05 M NaCl, pH 7.4, and 0.05% surfactant P-20) and the diluted samples were injected over the DNA surface for a selected time. A 10 mM glycine solution at pH 2.5 was used for flow cell surface regeneration. Kinetics fits and steady-state binding studies were carried out as described [28, 30]. Steady-state analysis was done by averaging the RU values (RU) in the plateau region of the sensorgrams over a selected time region at different compound concentrations. The binding constants were obtained from fitting plots of steady-state RU versus Cfree while kinetics fits were done in both the association and dissociation time regions [28, 30].

2.5. Quantitative DNase I Footprinting by Capillary Electrophoresis

To generate a 524 bp DNA fragment of the HPV16 genome containing three cognate sites for PA1 and beginning at nt 2150, two oligomers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, Iowa 52241). The forward primer sequence is: 5′-Fam-ATG TGA TAG GGT AGA TGA TGG AGG TG; the reverse primer sequence is: 5′-G CTC ATA CAC TGG ATT TCC GTT TTC GTC ATA. pUC19 with an HPV16 genome insert (Accession # AF125673) was used as the template. PCR settings were 55 °C/1 min annealing temperature, 68 °C/min extension temperature/time with 33 cycles. The fragment was purified using a 2% agarose gel and purified with Qiagen gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA 91355).

A 120 bp duplex was generated as described previously [27]. Its sequence is: Fam_ATGTGATAGGGTAGATGATGGAGGTGgagtttaatgaaatttctgcaagggtctgtaatatgttttgtaaattct aa CCTGGAGAGGAAGCCAAGTG tttttggttacaaccattagcag. The first sequence in capital letters is from HPV16 2150-2175. The sequence in lower case letters originates from HPV16 positions 2327–2377 and 2384–2406, which are the sequences surrounding the 5′-AAGCCA-3′ cognate target site (bolded). The underlined sequence is the same as the stem region of the DNA hairpin used for the above fluorescence studies and most SPR studies (i.e. the “long hairpin”).

For footprinting [31], duplex DNA was mixed with polyamide in TKMC buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM CaCl2), incubated at 37 °C for time periods varying from 4 h to overnight. PA concentrations as high as 60–80 nM were used to study weak binding sites. Similar footprinting results were obtained for all these incubation times. The mixture was digested with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI) for 5 min at 37 °C and quenched by adding 30 μL of 500 mM EDTA. The DNase I digested product was purified with Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and eluted with 30 μL of buffer. A few μL of the resulting samples were analyzed using an ABI 3100 Capillary Electrophoresis sequencer (Carlsbad, California). Data were processed using Genemarker V1.97 software (Softgenetics LLC, State College, PA), which integrates peak areas. Peak areas in the footprint were normalized to a neighboring peak not sensitive to PA concentration, plotted as fraction bound vs. PA concentration, and fit to the isotherm as described above.

2.6 Molecular Docking Studies

Preliminary molecular modeling studies were conducted using the SYBYL-X 2.0 software on the polyamide-DNA complexes to better understand the different structural components that cause the dramatic difference in the binding affinity. The crystal structure of an 8-ring cyclic polyamide (PDB ID: 3OMJ; Chenoweth, David M.; Dervan, Peter B. “Structural Basis for Cyclic Py-Im Polyamide Allosteric Inhibition of Nuclear Receptor Binding” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 14521.) was used as the initial template for our studies. The central six-base pairs of the 10-mer duplex DNA from the crystal structure (5′-CCAGTACTGG-3′) were mutated to the cognate sequence (5′-CCTGGCTTGG-3′) using the Mutate Monomer option of the Biopolymer-Composition module. Corresponding nucleobases were also mutated in the complementary strand of the DNA duplex. The flanking nucleobases at both ends were kept as GC base pairs to help lock the ends in place. This does not affect the docked models since the terminal base pairs are beyond the recognition site of the KA polyamides. The modified duplex structure was then energy minimized for 100 iterations to allow the mutated bases to minimize any unfavorable interactions. The final minimized DNA was visually inspected by overlaying with the DNA from the crystal structure to assure that there were no significant structural deviations. The cyclic polyamide (with two γ-turns) from the crystal structure (Im-Py-Py-Py-γ-Im-Py-Py-Py-γ) was modified to PA1 (dIm-Im-Py-Py-γ-Py-Im-Py-Py-Dp) or PA2 (dIm-Im-β-Py-γ-Py-Im-Py-Py-Dp) using the Sketch Molecule module in SYBYL. The two polyamides were also energy minimized to optimize the local geometry of the modified heterocycles and the β–linker. The free ends of the polyamides were constrained to maintain stacking in this process.

For the docking studies, two separate polyamide-DNA complexes (PA1 and PA2 with the modified recognition sequence) were constructed using the crystal structure (3OMJ) as the reference structure. The polyamides were carefully superimposed onto the cyclic polyamide of the crystal structure within the minor groove of the cognate sequence using the Fit Atoms option of the Align Compounds module. This option allows retaining the local geometry as well as the H-bond registry of unmodified heterocycles from the crystal structure. The manually docked polyamide-DNA complexes were then energy minimized using the Tripos force field and Conjugate Gradient method and a termination gradient of 0.05 kcal/(molÅ) or until a maximum of 10000 iterations was reached. The final energy minimized, docked polyamide-DNA complexes were visually inspected and analyzed using Chimera to help understand and rationalize the structural modifications in the polyamides that contribute to the differences observed in the binding affinity and kinetics of polyamide-DNA interactions.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Polyamide and DNA Target Design

To carry out the comparative biophysical studies of the effects on DNA binding of β/Py replacements at internal positions of eight-ring polyamides, we prepared the compound pairs shown in Figure 1. The resulting compounds all target part of the human COX-2 Ets-1 binding site [25, 34, 35].

Compounds PA1–4 comprise two isomer pairs (PA1/PA2 and PA3/PA4) that differ only by replacement of an internal Py building block by β-alanine. All four compounds were designed to recognize the same sequence, but they bind in different orientations, as shown in Figure 2. The essentially identical DNA hairpins used in this study are based on the human COX-2 promoter in the Ets-1 binding region. These hairpins were used in the present study as (a) dye derivatives, (b) unfunctionalized DNA and (c) 5′-biotin conjugates in order to measure DNA-PA dissociation constants and kinetic parameters of PA1–4 binding their cognate DNA sites. The only difference in hairpins used for fluorescence studies is the location of a TAMRA dye at T37 for PA1–2 and at T34 for PA3–4. In addition, the binding of PA1 and PA2 was studied by quantitative footprinting of a linear 120-bp DNA duplex. PA1 binding to a 524-bp DNA sequence with several cognate and noncognate (single bp mismatch) sites was also examined by quantitative footprinting, and SPR was performed on a noncognate hairpin treated with PA3 (see 3.3 below).

3.2. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

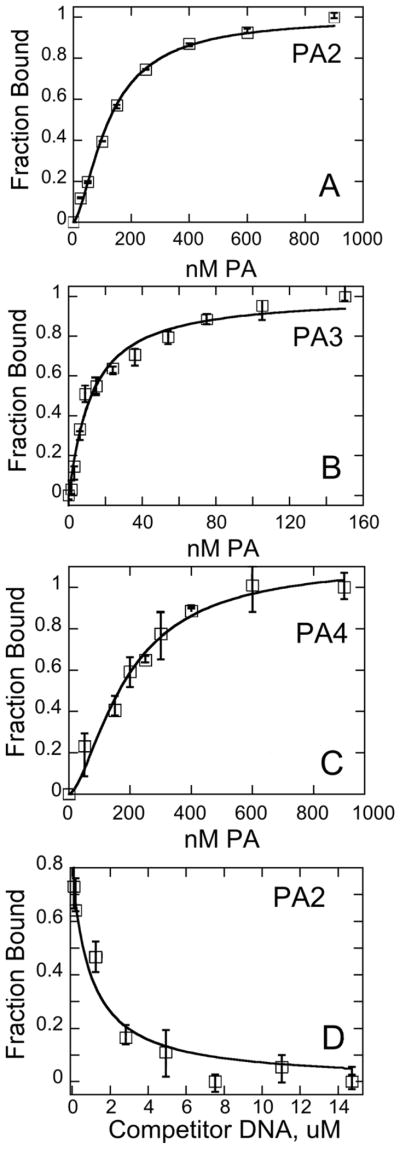

Isotherms were observed using relatively large and easily reproducible decreases in TAMRA fluorescence intensity upon PA binding (10–50% depending on PA and dye location). Binding isotherms for PA2–4 are shown in Figure 3A, B, C (for the isotherm of PA1, see Ref. [27]). Kds appear in Table 1. A small degree of sigmoidicity was observed in some cases (Fig. 3A and C; see also 4. Discussion).

Figure 3. Polyamide-DNA Binding as Observed via Fluorescence Spectroscopy.

Sample binding isotherms for PA2 (A), PA3 (B), and PA4 (C) toward TAMRA-labeled DNA hairpin as described in the text. (D) Sample competition experiment between an unlabeled DNA hairpin and a labeled DNA hairpin bound to PA2. Conditions: 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, 25 °C. Error bars refer to normalize d individual intensities that were averaged for each point. At least three individual Kd determinations were averaged to generate the data in the Tables.

Table 1.

Data for DNA Binding of PA1-PA4 to DNA Hairpin by Fluorescence (FL) and SPR.

| Cmpd. | Sequence | Kd/FL (nM)a | Kd/FL competition (nM)b | Kd/SPR (nM) | ka/SPR (M−1s−1) | kd/SPR (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA1 | dImImPyPyγ:PyImPyPyβDp | 2.3 ± 0.3d | 1.1 ± 0.2d | 1.12 ± 0.21 | 5.3 × 107 | 0.059 |

| PA2 | dImImβPyγ:PyImPyPyβDp | 170 ± 40 | 325 ± 150 | 83.4 ± 8.9 | tfc | tf |

| PA3 | dImPyPyPyγ:PyImImPyβDp | 11.0 ± 1.0d | ≤ 1.0 | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 1.2 × 107 | 0.0085 |

| PA4 | dImβPyPyγ:PyImImPyβDp | 120 ± 15 | 70 ± 30 | 106 ± 11 | tf | tf |

C-5 TAMRA dye substitution at T37 for PA1–2 and T34 for PA3–4.

From competition of unlabeled DNA with dye-labeled DNA.

tf: too fast to determine, most of the interaction occurs during filling of the flow cells and the dissociation occurs during filling with buffer.

Reproduced from Ref. [27]

To evaluate potential dye-related artifacts on the Kd, unlabeled DNA was used in competition with dye-labeled DNA (Fig. 3D; [27]); dyes were found not to interfere with interpretation (Table 1). Using this technique, we found that Kd values of ≤1 nM increased by ca. 100-fold when a single Py in PA1 was replaced by β to give PA2, and a similar increase in Kd occurred when a single internal Py was replaced in PA3 to give PA4.

3.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance

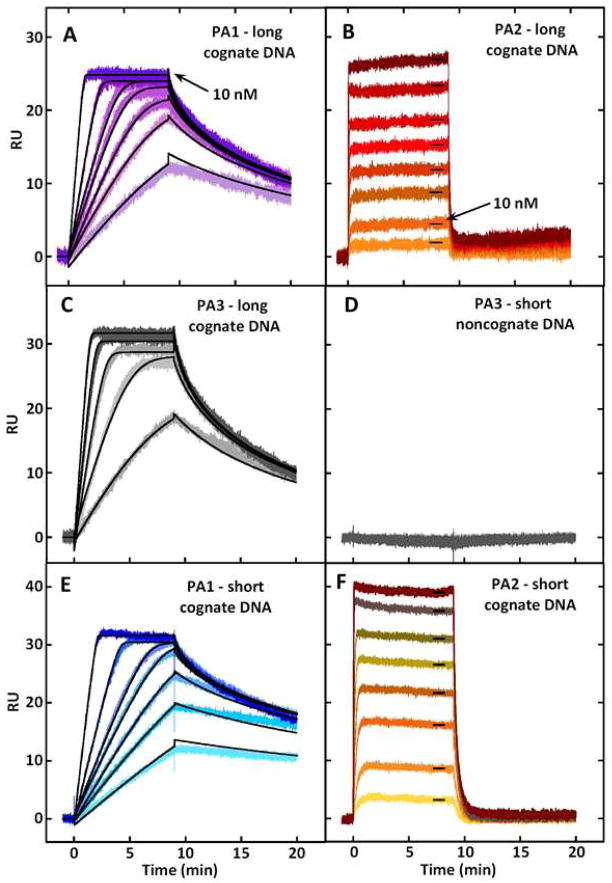

Using surface plasmon resonance, striking differences in behavior of PAs with and without an internal β residue are also easily seen in Figure 4A, B, which features SPR sensorgrams for PA1 and PA2 binding to the cognate DNA sequence in Figure 2. The concentrations required to saturate the binding sites in PA1 are well below those required for PA2. Further, the kinetics, particularly for dissociation, are much slower for PA1 than PA2 (Table 1). PA3 binds even more strongly than PA1 to the same DNA hairpin; sensorgrams for PA3 binding are shown in Figure 4C. The sensorgrams for PA4 are very similar to those for PA2 and are not shown. The sensorgrams for PA1 and PA3 do not reach a steady-state plateau until almost saturation binding and were fit with a single-binding site kinetic model to determine both kinetics and equilibrium constants for binding [28–30]. As can be seen in the figures, the fits are excellent.

Figure 4. Polyamide-DNA Binding as Observed via Surface Plasmon Resonance.

Sensorgrams for the interactions of PA1 (A), PA2 (B) and PA3 (C) with the 5′-biotin labeled long hairpin DNA sequence shown in Figure 2. (D) Sensorgram for the interactions of PA3 with the noncognate hairpin DNA sequence, 5′-biotin-CCTTGGAGAGTTTTCTCTCCAAGG-3′, with the hairpin loop bases underlined. SPR sensorgrams for the interaction of PA1 (E) and PA2 (F) with the short cognate DNA sequence (5′-biotin-CCTTGGCTTCTTTTGAAGCCAAGG-3′). Individual sensorgrams represent responses at different PA concentrations: concentrations for PA1 are 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 5.0 and 10.0 nM; concentrations for PA2 are 1.0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 100, 200 and 400 nM. The concentrations for PA3 are 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0 and 8.0 nM. Kinetic and steady-state fits were performed using BIAcore T100 Evaluation Software. As seen in (D), all polyamides showed no significant binding to the noncognate sequence.

The kinetics for PA2 and PA4 with DNA are too fast to fit with a kinetic model, but since they reach a steady-state, they were fit by using the steady-state RU values and a single binding site model [28–30]. In this case, the fits are also excellent (not shown) and the results are in Table 1. These results clearly illustrate the detrimental effects of β-alanine substitution for DNA binding with these PAs, conditions and DNA sequences.

For comparison with binding to the DNA shown in Figure 2, the binding of PA1 and PA2 to a shorter cognate sequence analog is shown in Figures 4E, F. As can be see, the sensorgrams are very similar to those in panels A and B for the same compounds with the longer sequence. Binding constants with the short sequence (Figures 4E, F) are 2–3 times higher than with the longer sequence (Figures 4A, B). The fact that no binding was detected by SPR between PA3 and a noncognate DNA hairpin (Figure 4D) provides additional support for highly selective binding of PA1 and PA3, both of which lack internal β residues, although this is not the case in other systems [36].

3.4. Quantitative DNase I Footprinting

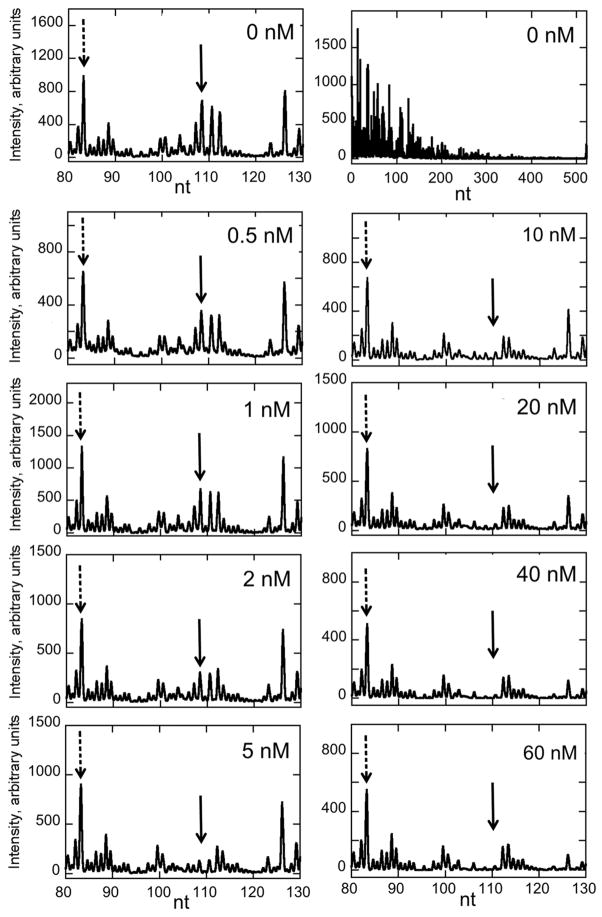

To determine how PA1 binds its target in a larger sequence context and to explore the generality of our observations from hairpin DNA-PA binding, we studied PA1 binding to an AT-rich 524 bp duplex from the HPV16 genome (2150–2673) using DNase I footprinting and capillary electrophoresis [32, 37]. Raw titration electropherograms for the first site (2258–2263) appears in Figure 5; electropherograms for the other two perfect sites (2378–2383 and 2407–2412) appear in Figures S4 and S5. A sample isotherm is given in Figure 6. As summarized in Table 2, PA1 binds to three cognate sites with high affinity. This provides further confirmation of the aforementioned observations about binding selectively with a small DNA hairpin, and indicates that PA1 binds its target avidly and specifically within the context of a long DNA sequence. Binding at single bp mismatch sites in the 524-mer was so weak as to be largely unobserved at [PA] ≤ 60 nM, with resulting noncognate Kd values conservatively estimated at ≥ 60–100 nM.

Figure 5.

Raw electropherograms illustrating the titration of the first PA1 site (2258–2263) on the 524 bp duplex using DNase I footprinting as observed by capillary electrophoresis. The top right panel illustrates the DNase I fragmentation pattern observed over the entire duplex. This distribution of intensities is observed routinely and account in part for the variable intensities across the fragment. Solid arrow indicates the footprint. Other variations among the titration point intensities are due to small sample handling variations, sample loading, etc. Integrated intensities are normalized to a peak that is DNase I insensitive to correct for this behavior (indicated by dashed arrow). See Methods for additional experimental details.

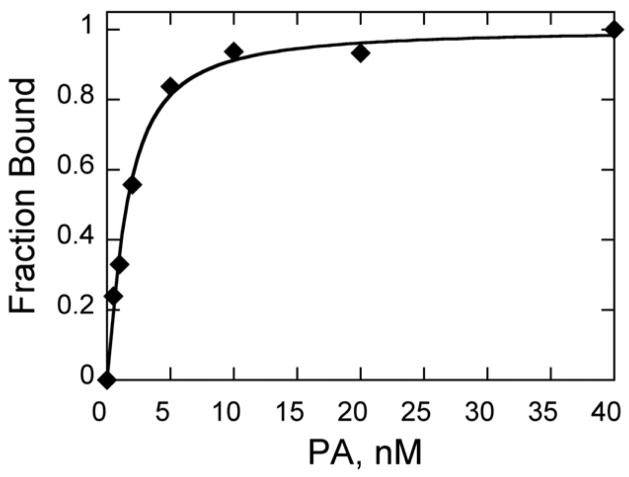

Figure 6. PA1-DNA Binding via Quantitative Footprinting and CE.

Sample isotherm of PA1 binding an AT rich 524 DNA duplex as detected by DNase I footprinting and capillary electrophoresis; conditions: 0.2 nM duplex; otherwise as per text. Data fit to a Kd of 1.6 nM.

Table 2.

Sites and Kd Values for PA1 bound to a linear, 524 bp DNAa molecule.

| Observed binding sites for PA1 | Positionb | Kd (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 5′-AGGCAT-3′ | 2258–2263 | 1.6±0.2 |

| 5′-AAGCCA-3′ | 2378–2383 | 3.3±1 |

| 5′-ATGCCA-3′ | 2407–2412 | 2.6±1 |

| 5′-AGGTAT-3′ | 2202–2207 | 60–100 |

| 5′-AGGTAA-3′ | 2306–2311 | >100 |

| 5′-TGGCCT-3′ (two sites) | 2585–2590 2626–2631 |

>60 |

Determined by quantitative DNase I footprinting; mismatches in bold.

Numbering system in the HPV16 genome.

To compare single site binding affinities of PA1 and PA2 for a linear dsDNA molecule larger than the above DNA hairpins, a 120 bp duplex with a single PA1/2 binding site was generated. The central part of the sequence is identical to the stem portion of our primary hairpin DNA target hairpin used for fluorescence and SPR studies (see Section 2.5 and Figure 2). The flanking sequences for the 120-mer were derived from a portion of the HPV16 genome predicted to contain no additional binding sites for PA1 or PA2. Sample raw electropherograms appear in Figures S6 and S7. Quantitative DNAse I footprinting of this duplex yields Kds of 1.1 ± 0.2 nM [27] and 80 ± 8 nM for PA1 and PA2, respectively. These data agree remarkably well with the results obtained by our other methods, providing additional evidence that Kds obtained with the relatively small DNA hairpins are indicative of affinities observed in larger DNA contexts.

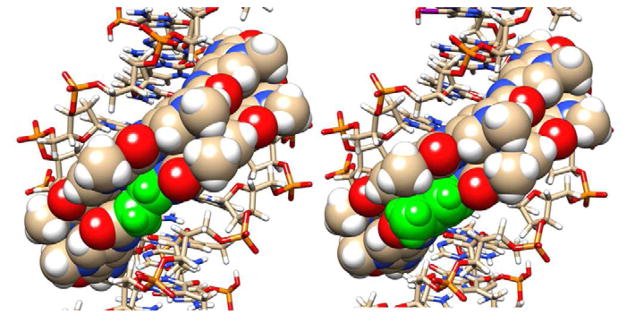

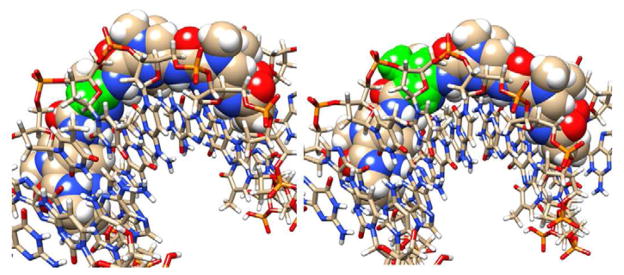

3.5 Docking of PA1 and PA2 to Cognate DNA

Figure 7 shows the results of a docking study for PA1 and PA2. As can be seen from the docked models, both PA1 and PA2 fit snugly into the minor groove at the cognate duplex DNA binding site as represented by the top strand, 5′-CCTGGCTTGG-3′. Some observations in the docked models help to understand the differences in binding constants for these compounds, although more detailed molecular dynamics experiments on the bound and free species will be required for a full understanding. The van der Waals stacking by the planar, aromatic pyrrole is better with the adjacent PA strand and the minor groove than it is with the aliphatic β group. Note, for example, the excellent stacking of the pyrrole with a deoxyribose from the DNA backbone and with the nearby polyamide residues, while the alkyl CH2 groups from β stack less effectively. It also is probably important that β has many more allowed conformations in solution than the rigid pyrrole, and that when both are locked into the bound conformation shown in Figure 7, the β group will cause a larger entropy loss. Other features such as amide –NH to nucleobase H-bonds are similar in the two docked models.

Figure 7. Docking of PA1 and PA2 to their cognate DNA sequence.

Views of PA1 (right side) and PA2 (left side) are shown docked into the minor groove of the cognate DNA binding site, 5′-TGGCT-3′. The pyrrole and the β in the same position in PA2 are shown in green while other atoms are colored as follows: Carbon, tan; Hydrogen, white; Oxygen, red, Nitrogen, blue, and Phosphorous, yellow. The DNA is shown as a ball and stick model and the polyamides as space filling representations. One view (A) is directly into the minor groove to indicate the excellent fit of the hairpin PAs into the binding site. The second view (B) is perpendicular to the bound compounds with the ImIm(Py or β)Py sequence on top.

4. DISCUSSION

As mentioned above (Section 3.2), slight cooperativity was observed in binding isotherms determined via fluorescence spectroscopy. To examine the effect of this curve shape on the calculated Kd values, data were fit to alternate versions of Eqn. 1 (i.e., nH fixed at 1 (Langmuir isotherm) and floated (Hill equation)). As shown in Table S1, similar Kd values were obtained from both Langmuir and Hill models with only marginal differences in the quality of fit (R value). Coupled with relatively small Hill coefficients (ranging from 1.2 to 1.9), these data indicate that the slight sigmoidal nature of some isotherms has no practical effect on interpretation. The physical basis of the observed mild cooperativity is unclear. However, the same behavior is sometimes observed when dimeric proteins bind single DNA sites [38]. Analogously, we speculate that the slight cooperative behavior comes from nestling of the two stems of the PA hairpin into the duplex. Alternatively, the dye could be contributing to the slight cooperativity observed.

Regarding binding kinetics, at concentrations of 10 nM and higher, all four PAs bind rapidly to DNA in SPR experiments and reach a steady state plateau. The dissociation rate constants, however, are much smaller for PA1 and PA3 than for PA2 and PA4. This observation suggests that all of the polyamides rapidly locate their DNA binding sites and associate within the minor groove. Once bound, however, PA1 and PA3 form exceptionally tight complexes that dissociate only very slowly from DNA.

Table 1 illustrates the excellent agreement found between fluorescence and SPR measurements for both the tight binding PA1 and PA3 and the weaker-binding PA2 and PA4, providing validation for both experimental approaches. These binding constants are also consistent with the literature for similar compounds, except that our trends are the reverse of reported trends. A number of previous reports are relevant to the present study and merit discussion; until the end, we restrict discussion here to 8-ring PA and their analogs, which recognize 6 bp DNA sequences. In two 8-ring PA lacking internal β residues, the authors found Kd values of 0.03 (PA5, ImPyPyPy-γ-ImPyPyPy-β-Dp) and 0.3 nM (PA6, ImPyPyPy-γ-PyPyPyPy-β-Dp) for binding to cognate DNA sequences [39]. Incorporation of (R)-2,4-diaminobutyric acid ((R)H2Nγ) in place of 4-aminobutyric acid (γ) as the gamma turn was reported to increase the binding affinities of hairpin PA 10-fold while retaining binding specificity [40]. Interestingly, the “parent” 8-ring PA7, PyPyPyPy-(R)H2Nγ-ImPyPyIm-β-Dp, binds to 5′-TNTACA-3′ with Kd = 0.06 nM and no sequence preference at nucleotide N, while introduction of an internal β, in PA8, PyPyPyPy-(R)H2Nγ-ImPy-β-ImβDp, gives a similar subnanomolar Kd to the parent PA7, but introduces 5 to 25-fold selectivity against noncognate sites, indicating that incorporation of the flexible β residue to the 5′-side of Im allowed, as intended, better alignment of Im N-3 with the exocyclic NH2 of G [26, 36, 40].

In dramatic contrast vs. 8-ring PA7, our 8-ring parent molecules PA1 and PA3 both bind with good affinity of ca. 1 nM and high specificity (conservatively 60- to 100-fold). Furthermore, when we introduced β residues to the 3′ side of Im in two cases (Figure 2), a 60- to 100-fold loss in binding affinity resulted, not the gain found with PA8 analogs. Finally, while longer PA molecules showed enhanced affinity and selectivity for 5′-GCGC-3′ upon introduction of pairs of β/Im and Im/β residues into a single PA [26], our use of one β/Im or Im/β pairing within a single 8-ring hairpin PA caused a dramatic loss of binding affinity, and we found no benefit to replacing a heterocyclic building block with an internal β for the recognition of 5′-TGGCTT-3′ and 5′-AGCCAA-3′ sequences.

The difficulty of binding for the polyamides with a single vs. the all-ring analogs is emphasized by the docking results shown in Figure 7. We were able to find no problems with hydrogen bonding interactions for the β-derivative PA2, which matched the H-bonding pattern of parent PA PA1 quite well. However, the significant loss of hydrophobic interactions and entropy is apparent for the DNA complex of PA2 compared to that of PA1.

5. CONCLUSIONS

While anomalies in DNA binding of β-substituted polyamides have been mentioned, few quantitative details of such behavior have been previously reported [24, 26]. We did not find improved binding strength and specificity on incorporating β instead of Py to generate a β/Im pairing in an 8-ring polyamide [36], we found the opposite for the set of compounds reported here. The binding constants and their trends reported here were derived largely from hairpin polyamide-hairpin DNA complexes related to the human COX-2 Ets-1 promoter site, but we also extended our observations to much larger 120-mer and 524-mer linear dsDNA sequences as well to show the generality of these observations. A docking study provided a framework for explaining the problems induced by introduction of a single β into a PA hairpin: the surface area for hydrophobic contacts appears greatly decreased for β relative to Py, and the entropy penalty for DNA binding is apparently high for PA2 compared to PA1. The binding results reported here took on additional significance for us because of our use of PA molecules as anti-human papillomavirus (HPV) agents in collaboration with NanoVir, LLC: libraries of compounds in which internal β for Py substitutions are shuffled throughout the sequence should target the same cognate binding site but produce both active and inactive compounds [5, 41]. The current report will help guide future PA design and structure-activity studies for our own labs and for unrelated PA studies.

Supplementary Material

We report anomalous DNA binding and recognition of β-alanine substituted polyamides

We compare thermodynamics/kinetics of DNA binding for β-alanine vs. pyrrole

Orthogonal methods were used: SPR, fluorescence and quantitative DNA footprinting

DNA targets included small hairpins, 120-mer dsDNA and 524 bp dsDNA

A single internal β-alanine weakened DNA binding and decreased binding specificity

Acknowledgments

We thank NIH (NIAID AI083803 to JKB, NIAID AI064200 to WDW) and NanoVir, LLC for financial support and the Danforth Plant Science Center for HRMS (NSF-DBI 0922879); we thank the reviewers for their helpful comments; and JKB thanks J. J. Shieh for SPR work on the prior, cited COX-2 project [25].

Footnotes

Declaration of Financial Interest

JKB declares that he is part owner of NanoVir, LLC.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION. Chemical characterization, additional sample raw capillary electropherograms and comparison of alternative fits for fluorescence binding data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

James K. Bashkin, Email: bashkinj@umsl.edu.

Cynthia M. Dupureur, Email: dupureurc@umsl.edu.

W. David Wilson, Email: wdw@gsu.edu.

References

- 1.Muzikar KA, Nickols NG, Dervan PB. Repression of DNA-binding dependent glucocorticoid receptor-mediated gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16598–16603. S16598/16591–S16598/16596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909192106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harki DA, Satyamurthy N, Stout DB, Phelps ME, Dervan PB. In vivo imaging of pyrrole-imidazole polyamides with positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13039–13044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806308105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinohara KI, Bando T, Sugiyama H. Anticancer activities of alkylating pyrrole-imidazole polyamides with specific sequence recognition. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2011;21:228–242. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328334d8f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueno T, Fukuda N, Tsunemi A, Yao EH, Matsuda H, Tahira K, Matsumoto T, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto Y, Nagase H, Sugiyama H, Sawamura T. A novel gene silencer, pyrrole-imidazole polyamide targeting human lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 gene improves endothelial cell function. J Hyperten. 2009;27:508–516. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283207fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards TG, Koeller KJ, Slomczynska U, Fok K, Helmus M, Bashkin JK, Fisher C. HPV episome levels are potently decreased by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Antivir Res. 2011;91:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh MP, Lown JW. Lexitropsins: design and development of sequence-selective DNA minor groove-binding agents as new chemotherapeutics. Stud Med Chem. 1996;1:49–171. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dervan PB, Edelson BS. Recognition of the DNA minor groove by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:284–299. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dervan PB, Doss RM, Marques MA. Programmable DNA binding oligomers for control of transcription. Current medicinal chemistry. Anti-cancer agents. 2005;5:373–387. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnett R, Melander C, Puckett JW, Son LS, Wells RD, Dervan PB, Gottesfeld JM. DNA sequence-specific polyamides alleviate transcription inhibition associated with long GAA.TTC repeats in Friedreich’s ataxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11497–11502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604939103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi T, Asami Y, Kitamura E, Suzuki T, Wang X, Igarashi J, Morohashi A, Shinojima Y, Kanou H, Saito K, Takasu T, Nagase H, Harada Y, Kuroda K, Watanabe T, Kumamoto S, Aoyama T, Matsumoto Y, Bando T, Sugiyama H, Yoshida-Noro C, Fukuda N, Hayashi N. Development of Pyrrole-Imidazole Polyamide for Specific Regulation of Human Aurora Kinase-A and -B Gene Expression. Chem Biol. 2008;15:829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dose C, Farkas ME, Chenoweth DM, Dervan PB. Next generation hairpin polyamides with (R)-3,4-diaminobutyric acid turn unit. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6859–6866. doi: 10.1021/ja800888d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren CL, Kratochvil NC, Hauschild KE, Foister S, Brezinski ML, Dervan PB, Phillips GN, Jr, Ansari AZ. Defining the sequence-recognition profile of DNA-binding molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:867–872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farkas ME, Tsai SM, Dervan PB. Alpha-diaminobutyric acid-linked hairpin polyamides. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:6927–6936. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bando T, Minoshima M, Kashiwazaki G, Shinohara K-i, Sasaki S, Fujimoto J, Ohtsuki A, Murakami M, Nakazono S, Sugiyama H. Requirement of β-alanine components in sequence-specific DNA alkylation by pyrrole-imidazole conjugates with seven-base pair recognition. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:2286–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki S, Bando T, Minoshima M, Shinohara K-i, Sugiyama H. Sequence-specific alkylation by Y-shaped and tandem hairpin pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:864–870. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishijima S, Shinohara K, Bando T, Minoshima M, Kashiwazaki G, Sugiyama H. Cell permeability of Py-Im-polyamide-fluorescein conjugates: Influence of molecular size and Py/Im content. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:978–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minoshima M, Bando T, Shinohara K, Kashiwazaki G, Nishijima S, Sugiyama H. Comparative analysis of DNA alkylation by conjugates between pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides and chlorambucil or seco-CBI. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeshima K, Janssen S, Laemmli UK. Specific targeting of insect and vertebrate telomeres with pyrrole and imidazole polyamides. Embo J. 2001;20:3218–3228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen S, Durussel T, Laemmli UK. Chromatin opening of DNA satellites by targeted sequence-specific drugs. Mol Cell. 2000;6:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babu B, Liu Y, Plaunt A, Riddering C, Ogilvie R, Westrate L, Davis R, Ferguson A, Mackay H, Rice T, Chavda S, Wilson D, Lin S, Kiakos K, Hartley JA, Lee M. Design, synthesis and DNA binding properties of orthogonally positioned diamino containing polyamide f-IPI. Biochem Biophysical Res Com. 2011;404:848–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sielaff A, Cooper A, Mackay H, Brown T, O’Hare C, Kluza J, Kotecha M, Le M, Hochhauser D, Hartley JA, Lee M. Binding of f-PIP and JH-37 to the inverted CCAAT box-2 of the topoisomerase IIa promoter. Abstracts of Papers, 233rd ACS National Meeting; Chicago, IL, United States. March 25–29, 2007; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy PM, Dexter R, Bruice TC. DNA sequence recognition in the minor groove by hairpin pyrrole polyamide-Hoechst 33258 analogue conjugate. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3803–3807. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehley JA, Melander C, Herman D, Baird EE, Ferguson HA, Goodrich JA, Dervan PB, Gottesfeld JM. Promoter scanning for transcription inhibition with DNA-binding polyamides. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1723–1733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1723-1733.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dervan PB, Urbach AR. The importance of β-alanine for recognition of the minor groove of DNA. Essays Contemp Chem. 2001:327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillion DP, Crowley KS, Bashkin JK, Schweitzer BA, Burnette BL, Woodard SS. WO 2003040337 A2 20030515. Polyamide modulators of COX2 transcription, from PCT International Patent Appln. 2003:40. Chemical Abstracts Number(CAN)138:396243.

- 26.Turner JM, Swalley SE, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Aliphatic/Aromatic Amino Acid Pairings for Polyamide Recognition in the Minor Groove of DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6219–6226. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dupureur CM, Bashkin JK, Aston K, Koeller KJ, Gaston KR, He G. Fluorescence assay of polyamide-DNA interactions. Anal Biochem. 2012;423:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Wilson WD. Quantitative Analysis of Small Molecule–Nucleic Acid Interactions with a Biosensor Surface and Surface Plasmon Resonance Detection. In: Fox KR, editor. Methods Mol Biol. Springer; NY: 2010. pp. 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myszka DG. Improving biosensor analysis. J Mol Recog. 1999;12:279–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199909/10)12:5<279::AID-JMR473>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen B, Tanious FA, Wilson WD. Biosensor-surface plasmon resonance: Quantitative analysis of small molecule-nucleic acid interactions. Methods. 2007;42:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trauger JW, Dervan PB. Footprinting methods for analysis of pyrrole-imidazole polyamide/DNA complexes. Methods Enzymol. 2001;340:450–466. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)40436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitra S, Shcherbakova IV, Altman RB, Brenowitz M, Laederach A. High-throughput single-nucleotide structural mapping by capillary automated footprinting analysis. Nucl Acids Res. 2008;36:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baird EE, Dervan PB. Solid Phase Synthesis of Polyamides Containing Imidazole and Pyrrole Amino Acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6141–6146. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garvie CW, Pufall MA, Graves BJ, Wolberger C. Structural analysis of the autoinhibition of Ets-1 and its role in protein partnerships. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45529–45536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickinson LA, Trauger JW, Baird EE, Dervan PB, Graves BJ, Gottesfeld JM. Inhibition of Ets-1 DNA binding and ternary complex formation between Ets-1, NF-κB, and DNA by a designed DNA-binding ligand. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12765–12773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CC, Ellervik U, Dervan PB. Expanding the recognition of the minor groove of DNA by incorporation of β-alanine in hairpin polyamides. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:653–657. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson DO, Johnson P, McCord BR. Nonradiochemical DNase I footprinting by capillary electrophoresis. ELECTROPHORESIS. 2001;22:1979–1986. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200106)22:10<1979::AID-ELPS1979>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowen LM, Dupureur CM. Investigation of restriction enzyme cofactor requirements: A relationship between metal ion properties and sequence specificity. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12643–12653. doi: 10.1021/bi035240g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trauger KW, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Recognition of DNA by designed ligands at subnanomolar concentrations. Nature. 1996;382:559–561. doi: 10.1038/382559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dervan PB, Bürli RW. Sequence-specific DNA recognition by polyamides. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:688–693. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher C, Bashkin JK, Crowley KS, Sverdrup FM, Garner-Hamrick PA, Phillion DP. WO 2005033282 A2 20050414. Polyamide Compositions and Therapeutic Methods for Treatment of Human Papilloma Virus, from PCT International Patent Appln. 2005:53. Chemical Abstracts Number(CAN) 142:367645.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.