Abstract

Purpose

To compare the performance of fat fraction quantification using single- and dual- correction methods in patients with fatty liver, using MR spectroscopy (MRS) as the reference standard.

Materials and Methods

From a group of 97 patients, 32 patients with hepatic fat fraction greater than 5%, as measured by MRS, were identified. In these patients, chemical shift encoded fat-water imaging was performed, covering the entire liver in a single breath-hold. Fat fraction was measured from the imaging data by post-processing using 6 different models: single- and dual- correction, each performed with complex fitting, magnitude fitting and mixed magnitude/complex fitting to compare the effects of phase error correction. Fat fraction measurements were compared to co-registered spectroscopy measurements using linear regression.

Results

Linear regression demonstrated higher agreement with MRS using single- correction compared with dual- correction. Among single- models, all 3 fittings methods performed similarly well (slope = 1.0 ± 0.06, r2=0.89–0.91).

Conclusion

Single- modeling is more accurate than dual- modeling for hepatic fat quantification in patients, even in those with high hepatic fat concentrations.

Keywords: T2* correction, R2* correction, hepatic steatosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, fat quantification, fat fraction

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity and the related condition known as metabolic syndrome is rising dramatically in developed nations (1). Metabolic syndrome is a collection of associated conditions that includes atherosclerosis, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is characterized by the intracellular accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes (hepatic steatosis), and affects approximately 30% of adults in the US (2). Steatosis can progress to liver injury, cirrhosis, and even portal hypertension or hepatocellular carcinoma (3). The current reference standard for assessment of fatty liver is biopsy, which is expensive, risky and suffers from high sampling variability. For these reasons there is an unmet need for accurate, precise, and non-invasive methods to measure liver fat content.

Magnetic resonance (MR) techniques are non-invasive and have been shown to be highly sensitive to fat. MR spectroscopy (MRS) is able to accurately quantify the proton density fat fraction (PDFF, the fraction of MR-visible protons contained within fat molecules, or FF for short) within a small volume (2,4,5). However, MRS suffers from sampling variability and lack of spatial coverage (4), and requires specialized post-processing from expert users, all limiting its clinical utility.

Chemical shift-encoded MRI techniques are able to overcome these limitations, and provide volumetric measurements of FF with high spatial resolution (6,7). These methods acquire multiple images at different echo time (TE) shifts, and separate water and fat signals through post-processing (8,9,10). Subsequently, FF maps can be calculated from the separated water and fat images. In order to obtain accurate FF measures, a number of confounding factors must be addressed, including field inhomogeneities (10,11,12), T1 bias (13), noise bias (13), spectral complexity of fat (14,15), and decay (15,16).

Although FF can be estimated with chemical shift-based methods that neglect decay, the presence of decay, particularly in patients with iron overload, but even in those without excess iron, leads to significant error in hepatic FF estimates (6,7,15,17,18). Most approaches that use correction assume a common decay rate for both water and fat signals (“single-”), which has been shown to be effective for accurate fat quantification (19), (7). However, a single- model may not accurately model the effects of the two separate signals of water and fat if the decay rates of water and fat are not equal. This has led to methods that allow independent decay rates (“dual-”) for water and fat. These methods have been demonstrated to improve the accuracy of fat quantification in phantom studies (20).

Unfortunately, dual- correction is mathematically complicated, and has significantly worse noise performance and instability than single- correction methods (21), particularly at very low or very high FF. Therefore, although dual- correction may reduce bias by more accurately modeling the underlying physics, the instability and worsening SNR performance adversely affects its accuracy for FF quantification. To date, no clinical comparisons have been made on the impact of single- vs. dual- correction on measurement of FF. Comparison of these two approaches in clinical studies is the major purpose of this work.

In order to quantify FF over a complete dynamic range from 0–100%, complex-valued signals must be used. However, the signal may contain phase errors (for example, due to eddy currents), and bias in FF may be introduced as a result of these phase errors. This bias can be minimized by discarding the phase information and using only the magnitude of the signal (15,22). However, discarding the phase information leads to lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the FF estimates (22,23). Fortunately, the first echo is often the only echo affected by phase errors (24) and a recently described mixed fitting method that uses the magnitude of the first echo, and the complex data for subsequent echoes can be used to avoid bias in FF estimates while maintaining good SNR performance of the FF estimates (25). Further, the combined impact of correction and phase error correction methods has not been studied in clinical data. Therefore, we will also compare complex, magnitude and mixed fitting methods for both single- and dual- modeling.

Thus, there are two main purposes of this work: assess the accuracy of FF measurements using single- correction compared with dual- correction methods using MRS as the reference standard, and to examine the performance of phase error correction methods in combination with the two correction methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Modeling of R2* Decay

The signal model at the echo time tn for a spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) acquisition with N echoes, and a complex spectral model of fat can be expressed as (20):

| [1] |

where ρW and ρF are the amplitudes of water and fat signals, respectively, is the decay rate of water signal, is the decay rate of fat signal, fB is the frequency shift due to local magnetic field inhomogeneities, fF,p are the known frequencies for the multiple spectral peaks of the fat signal relative to the water peak, αp are the relative amplitudes of the fat signal such that , and tn = t1,…,tN are the echo times. Although the fat signal has multiple peaks, we have assumed a common decay rate , for all fat peaks; this approximation greatly decreases the complexity and noise sensitivity of the signal model (26). Since the protons on a single triglyceride molecule all share a very similar microscopic magnetic field environment (27), it is likely that assigning a common decay rate to all the fat peaks is a reasonable assumption. Apart from this approximation, the signal model is general; however, the need to estimate independent values for water and fat (“dual-”) still leads to very noisy fat quantification results. Additionally, the fat component is almost always the minority component and typically quite small (<5–15%), leading to instability and noisy estimates of . Thus, using dual- leads to poor noise performance and instability in both theory and practice (26,28).

In order to obtain FF estimates with improved noise performance, the signal model may be simplified further by an additional assumption that is close in value to , and the two decay rates may be represented by a single value, i.e., (19). The signal model then becomes:

| [2] |

where is the single decay rate for both water and fat, and all other parameters are as previously described. The fitting is performed with a nonlinear least-squares approach, utilizing the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (26).

Addressing Phase Errors

Phase errors in the acquired data have recently been recognized as a source of bias in FF measurement techniques that use complex fitting methods, i.e., where both the magnitude and phase of the acquired data are used for fat-water separation (22,25). In order to address these phase errors, one can simply discard the phase of the signal from all TEs, using only the magnitude information for fat-water separation and FF estimation. Magnitude fitting has the advantage of insensitivity to phase errors introduced by eddy currents (15,22), but has degraded SNR compared to complex fitting, because part of the acquired data (i.e., phase) has been discarded (23,25). Since the first echo is often the most affected by phase errors, a “mixed fitting” method was recently introduced (25). In mixed fitting, the phase of the first echo is discarded, but the phases of the remaining echoes are kept (21). This has the effect of avoiding bias related to eddy current while maintaining most of the high noise performance of complex fitting.

In this work, three different fitting methods were used for each correction method (single and dual): magnitude, complex, and mixed fitting, for a total of 6 different fitting methods.

Patients

The patient data examined in this paper has been previously used in separate studies (7,29); however, all source data were entirely reprocessed for this study. After obtaining informed consent, 97 patients scheduled for clinical abdominal MRI were recruited for two IRB-approved studies. The patient population included 51 women, and 45 men. Single-voxel spectroscopy and chemical shift-encoded imaging were performed on each patient. Out of all 97 patients, those with FFs above a threshold of 5%, as measured from the spectroscopy data (32 patients), were considered in this study. A FF threshold was imposed since fatty liver disease is defined as a FF above 5% (2). Further, the dual- estimate is unstable at low FFs (21,30). In addition, the benefits of dual- correction are minimal below this FF value, as the decay rate of water dominates over that of fat, since the majority of the signal is from water.

Spectroscopy

Single-voxel MR spectroscopy was acquired for the reference standard of FF. T2-corrected single-voxel stimulated echo acquisition mode (STEAM) (31) was used for 1H MRS rather than point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS), due to the relative insensitivity of STEAM to J-coupling (32). Five single-average spectra with different TEs (to correct for T2 decay) were acquired from a 2.0×2.0×2.5-cm3 voxel in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe. The voxel was placed in an area containing no large vessels or bile ducts. Other spectroscopy parameters included TR=3500 ms (to minimize T1 bias), TE=10, 20, 30, 40, 50 ms, minimum mixing time = 5 ms, receiver bandwidth = ±2.5 kHz, readout points = 2048, scan time = 21 s in a single breath hold. Measurements of FF were obtained from the STEAM data using the AMARES fitting algorithm in jMRUI, including correction for T2 decay (29), and spectral prior knowledge (33).

The possible need for dual- modeling is driven by potential difference between the decay rates of fat and water. However, the actual values of for water and fat that coexist in fatty liver are not well understood. In order to measure these values, both spectroscopic acquisition fitting, as well as dual- fat quantification (which estimates and ), can be performed. Both methods provide estimates of and , which can then be used to calculate the expected bias that would result from moving from dual- correction to single- correction. However, due to the inherent instability and reduced noise performance of dual- correction, estimates of water and fat based on the line-widths from the MRS acquisition are generally thought to be more reliable.

Spectroscopy data for FF>10% were re-processed using jMRUI, which used spectral fitting with prior knowledge (33), to obtain estimates of and . The threshold of FF=10%, rather than 5%, was used here in order to ensure a relatively less noisy estimate of , since the noise level of an estimate depends on the strength of the signal. Since an exponential decay in the time domain is equivalent to a Lorentzian in the frequency domain, two values of for each spectroscopic signal were obtained by fitting two Lorentzians to the frequency data. One Lorentzian was fitted to the water peak, and one Lorentzian to the methylene peak at 1.3 ppm (33), using the AMARES algorithm (34).

Importantly, we do not expect the values from this Lorentzian fitting process on spectroscopic data to agree with the values from the imaging data, due to differences in voxel size. Macroscopic susceptibility gradients across the voxel will cause additional dephasing that may increase the apparent decay rates. Fortunately, this increase in decay rate will be equal for water and fat (assuming relatively uniform distribution of water and fat in the voxel). Mathematically, the observed of water and fat can be described as:

| [3] |

| [4] |

where is the additional decay rate common to all species within a voxel, due to macroscopic field inhomogeneities across the voxel. Spectroscopy uses a larger voxel than imaging, therefore more dephasing (and larger ) occurs due to the larger number of isochromats contained in the larger voxel. However, the difference between and should be approximately independent of :

| [5] |

and therefore any difference between the water and fat should be similar to those observed by imaging.

Each acquisition had 5 separate spectroscopic signals, one for each TE. In order to minimize the effects of noise, the 5 fitted and values were averaged to obtain one and one value, respectively, for each acquisition. These values were then used to calculate worst-case errors in the estimation of fat fraction, as described below in “Worst-Case Error Calculation”.

Imaging

Imaging was performed at 1.5T (Signa HDxt; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using an eight-channel phased-array torso coil. A multi-echo 3D SPGR acquisition was performed on the liver, using flyback readout gradients. Imaging parameters included: 6 echoes/TR, TR = 13.7 ms, TE1 = 1.3 ms, ΔTE = 2.0 ms, bandwidth = ±125 kHz, FOV = 35×35 cm, flip angle = 5° to minimize T1 related bias, matrix = 256×128, 24 cm coverage in the S-I direction, and slice thickness = 10 mm. Parallel imaging acceleration using an autocalibrated data-driven method (ARC, Autocalibrating Reconstruction for Cartesian acquisition) (35) was used in order to obtain sufficient coverage while keeping the scan time (21 seconds) to a single breath hold, with a net acceleration factor of 2.2.

Six different fitting methods were then applied to each raw data set, to obtain fat and water images with different combinations of correction and fitting method. Specifically, magnitude, complex, and mixed fitting methods were used, each with a single- model and a dual- model. The fat images (ρF) and water images (ρW) were used to compute FF, pixel by pixel, using a magnitude discrimination method (13) to avoid noise related bias, i.e.:

| [6] |

FF was measured from the FF maps, after co-localization with the MRS, performed by taking the average of a 2.0 × 2.0 cm2 region of interest (ROI) from the FF map in the slice closest to the spectroscopic voxel, and the FF in the slices immediately inferior and superior. Three slices were used for averaging, since the spectroscopic acquisition was performed on a 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.5 cm3 ROI, and the imaging slice thickness was 1.0 cm. The imaging and spectroscopy acquisitions were performed at different breath holds, leading to some small error in co-localization. The same ROIs were used for all 6 reconstructions to ensure good co-localization with the different reconstruction and correction methods. Differences in noise performance among the 6 reconstructions were quantified by measuring the standard deviation of the ROIs placed in the FF and maps.

Worst-Case Error Calculation

In order to assess the bias in FF incurred by single- modeling, we performed a worst-case error simulation in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Chemical shift-encoded signals were generated using a dual- model (Eq. 1) as the truth, and subsequently fitted using a single- model (Eq. 2) over a range of fat-fractions from 0–100%. The difference between the true fat-fraction and the apparent fat-fraction, estimated using the single- model is the bias that would result from using single- correction. The worst-case situation would occur with large differences between and , while assuming a single- model (i.e., no difference between and ).

The “true” and used for the simulation were obtained from performing Lorentzian fitting on the STEAM data, as described above. As mentioned above, we do not expect the values to be the identical between imaging and spectroscopy, but the differences between and should be very similar.

The data point pair obtained from the Lorentzian fitting that had the greatest difference measured from the 20 subjects with FF > 10% was used (e.g., the largest value for ) for the “worst-case” dual- simulation, assuming typical TE values for imaging (TE1=1.2 ms, ΔTE=2.0 ms, 6 echoes), and the spectral model of fat reported by Hamilton et al (33). The use of this spectral model has been shown to improve estimation of the iterative least-squares approach (14).

Linear regression

All linear fits and P-values were calculated with R, a free software environment for statistical computation (36).

RESULTS

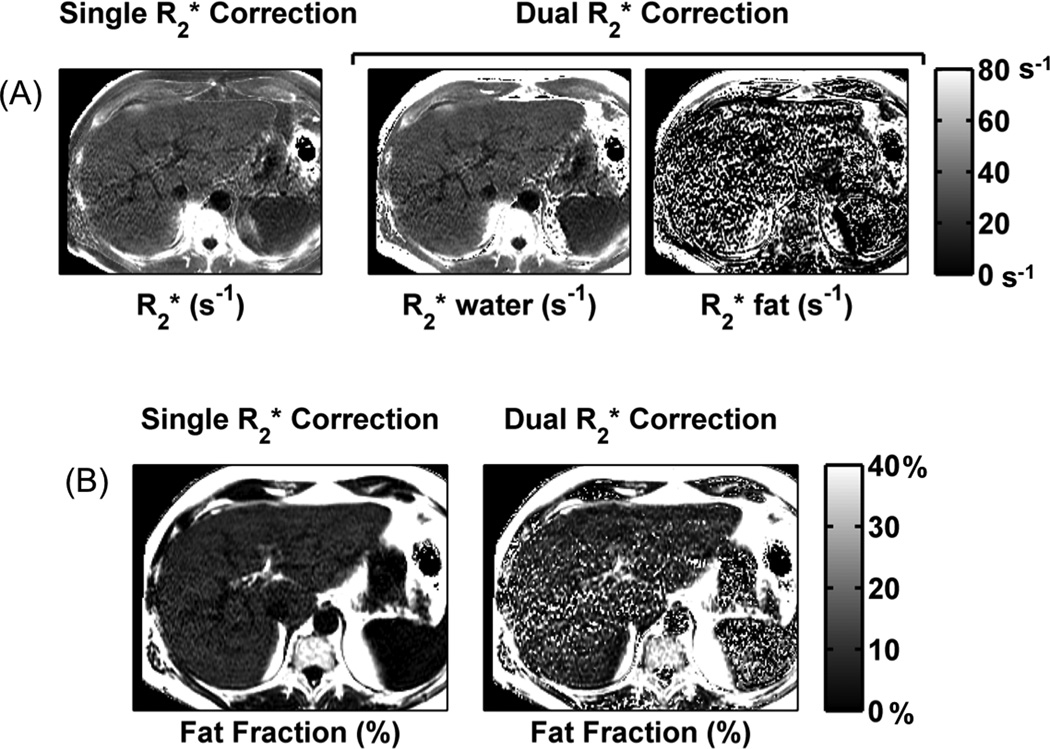

Dual- fitting methods are very noisy, as seen qualitatively in Fig. 1 where the FF maps reconstructed used dual- correction contain noticeably more noise than the FF maps reconstructed using single- correction. These results are summarized in Table 1 for the 32 subjects. From this table, it can be seen that the average standard deviations across the 32 subjects show substantial increases using dual- correction. In addition, both complex fitting and magnitude fitting have superior noise performance compared to magnitude fitting, as expected. Note that the actual value of the standard deviation is not very meaningful. However, assuming that the tissue is homogenous within the ROI, the relative values of the standard deviations of the colocalized ROI are a meaningful measure of the noise levels.

Figure 1.

Dual- modeling is associated with greater noise than single- modeling. Axial maps shows noticeably more noise using dual- modeling than single- modeling. Similarly, FF maps estimated using single- correction show markedly higher noise performance than those obtained using dual- correction.

Table 1. Noise measurements in imaging data.

Average standard deviations in FF and measurements are measured across the 32 subjects with FF > 5%. Values are reported as the average of the standard deviations within the ROIs measured from the 32 patients ± the standard deviation across the 32 patients.

| Model | Parameter | Complex | Mixed | Magnitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Single- |

FF (%) | 3.53 ± 2.12 | 4.10 ± 1.97 | 6.38 ± 3.78 | |

|

|

6.48 ± 4.37 | 5.91 ± 2.85 | 5.78 ± 2.69 | ||

|

Dual- |

FF (%) | 28.88 ± 43.78 | 19.18 ± 22.18 | 14.03 ± 2.78 | |

|

|

6.12 ± 2.99 | 6.50 ± 3.45 | 7.61 ± 7.59 | ||

|

|

143.38 ± 108.34 | 121.76 ± 87.98 | 109.67 ± 51.55 | ||

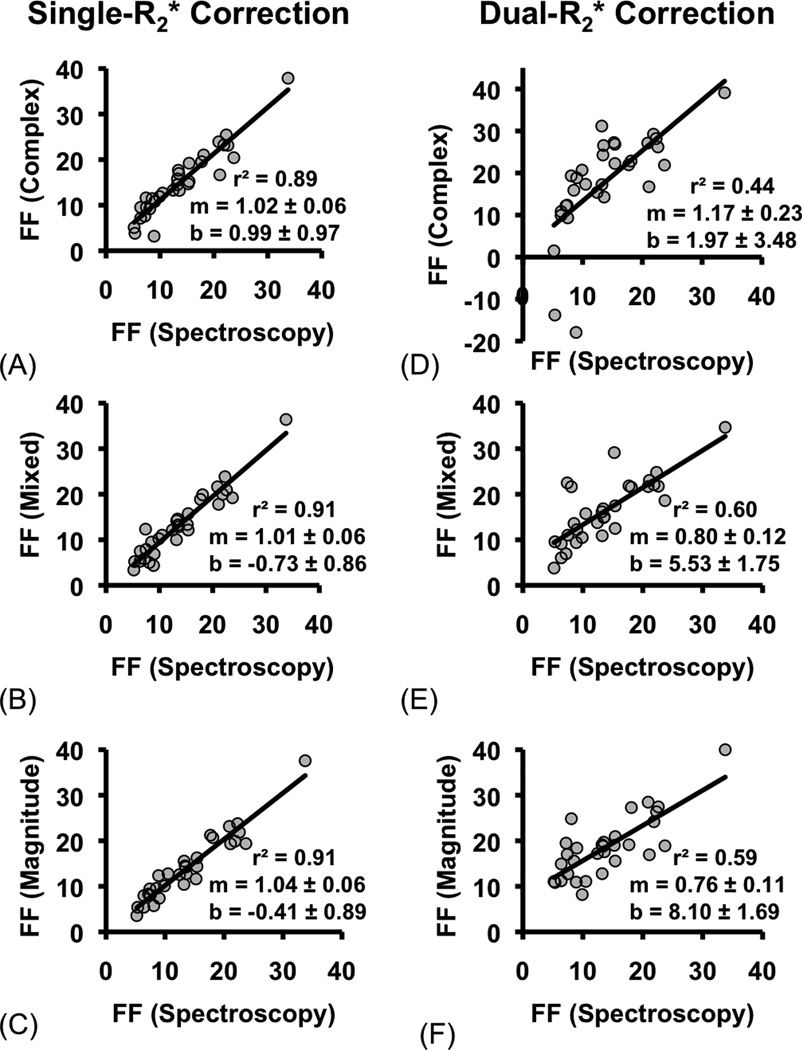

In Fig. 2a–c, FF measured using single- correction with complex fitting (Fig. 2a), mixed fitting (Fig. 2b) and magnitude fitting (Fig. 2c) are plotted against FF measured with MRS. FF measured using all three fitting methods show excellent correlation and agreement with MRS.

Figure 2.

Single- correction shows greater agreement with spectroscopy measurements than dual- correlation for quantification of fat fraction. FF estimated using three different single- (a.–c.) and dual- (d.–f.) models of complex, mixed, and magnitude fitting are plotted against FF co-localized and measured with spectroscopy. The dual- fits are very noisy at low FF: for example, the complex fit has some negative-valued FF estimates between 5–10%. Linear regression was performed, and the slope (m), intercept (b), and r2 of the fit are shown. The slope and intercept are displayed as the average value plus/minus the standard deviation.

Figure 2d–f plots the results of FF measured using dual- correction with complex fitting (Fig. 2d), mixed fitting (Fig. 2e) and magnitude fitting (Fig. 2f), along with results from linear regression. Markedly worse correlation and agreement is seen with all fitting methods used in combination with dual- correction (see Table 2). Complex fitting even leads to negative-valued estimates for FF. Overall, the poorer performance of the dual- regression can be explained by the increased noise associated with dual fitting (21,30).

Table 2. Linear fitting between FF measurements.

Linear regression and P-values show the degree of agreement between the FF from the 6 reconstruction methods and the FF from spectroscopy.

|

model |

Recon method |

Slope (m) |

P-value for m=0 |

P-value for m=1 |

Intercept (b, in s−1) |

P-value for b=0 |

r2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Single- |

Complex | 1.02 ± 0.06 | 4.5×10−16 | 0.60 | 0.99 ± 0.97 | 0.32 | 0.89 | |

| Mixed | 1.01 ± 0.06 | <2×10−16 | 0.59 | −0.73 ± 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.91 | ||

| Magnitude | 1.04 ± 0.06 | <2×10−16 | 0.74 | −0.41 ± 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.91 | ||

|

Dual- |

Complex | 1.17 ± 0.23 | 1.9×10−5 | 0.76 | 1.97 ± 3.48 | 0.57 | 0.44 | |

| Mixed | 0.80 ± 0.12 | 1.2×10−7 | 0.045 | 5.53 ± 1.75 | 3.6×10−3 | 0.60 | ||

| Magnitude | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 1.5×10−7 | 0.021 | 8.10 ± 1.69 | 4.2×10−5 | 0.59 | ||

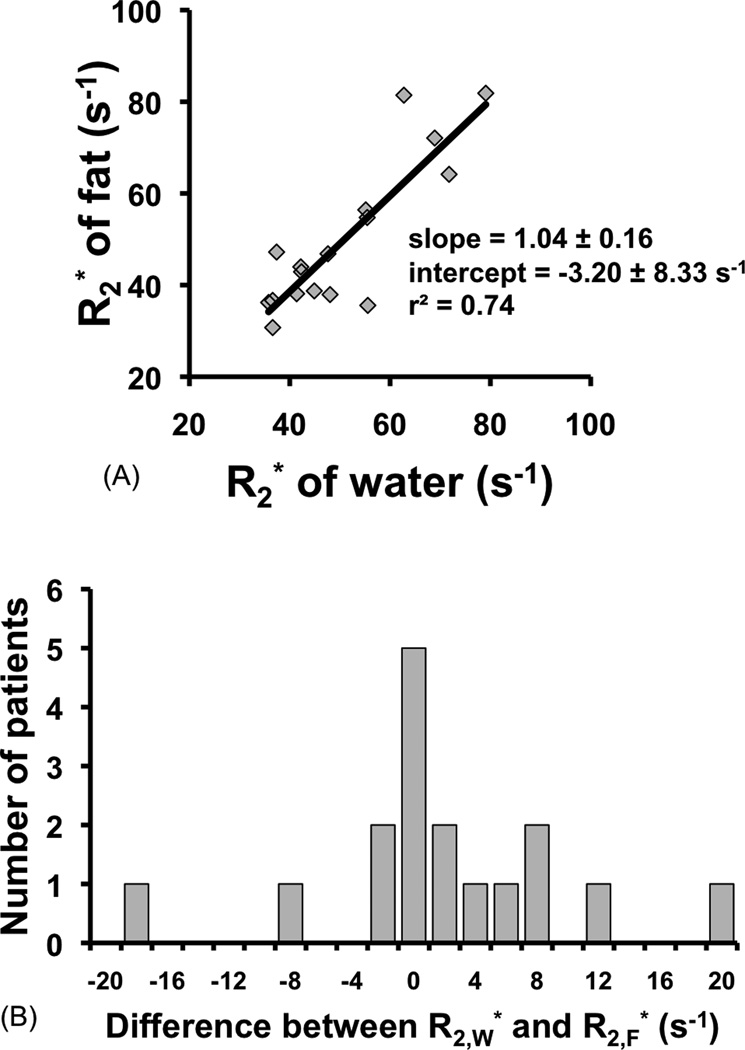

The results of the estimates for water and fat signals made using MRS are shown in Fig. 3a. As seen in this figure, which plots against , measured from MRS linewidth, the for water and fat show close agreement, i.e., overall, the of water and fat signals is very similar, indicated by a slope of 1.04 ± 0.16 and intercept −3.20 s−1 ± 8.33 s−1. The mean difference between the two values is 0.95 s−1 ± 8.28 s−1, which is very small. The greatest single difference between the two was 20 s−1 with and . This is the data pair used in the subsequent error simulation to determine the worst-case bias that could result from using single- correction.

Figure 3.

The of fat and water are very similar. This figure plots the of fat and water measured in the liver using MRS data fit to a two-peak Lorentzian model (water peak and methylene peak). The fat and water values are fitted linearly (a.), and also displayed as a histogram of the difference between the fat and water values (b.). The slope and intercept for the linear fit in (a.) are not significantly different from 1 and 0 respectively, as shown by their P-values (0.78 and 0.71 respectively), indicating that on average, the of water and fat are very similar in the liver.

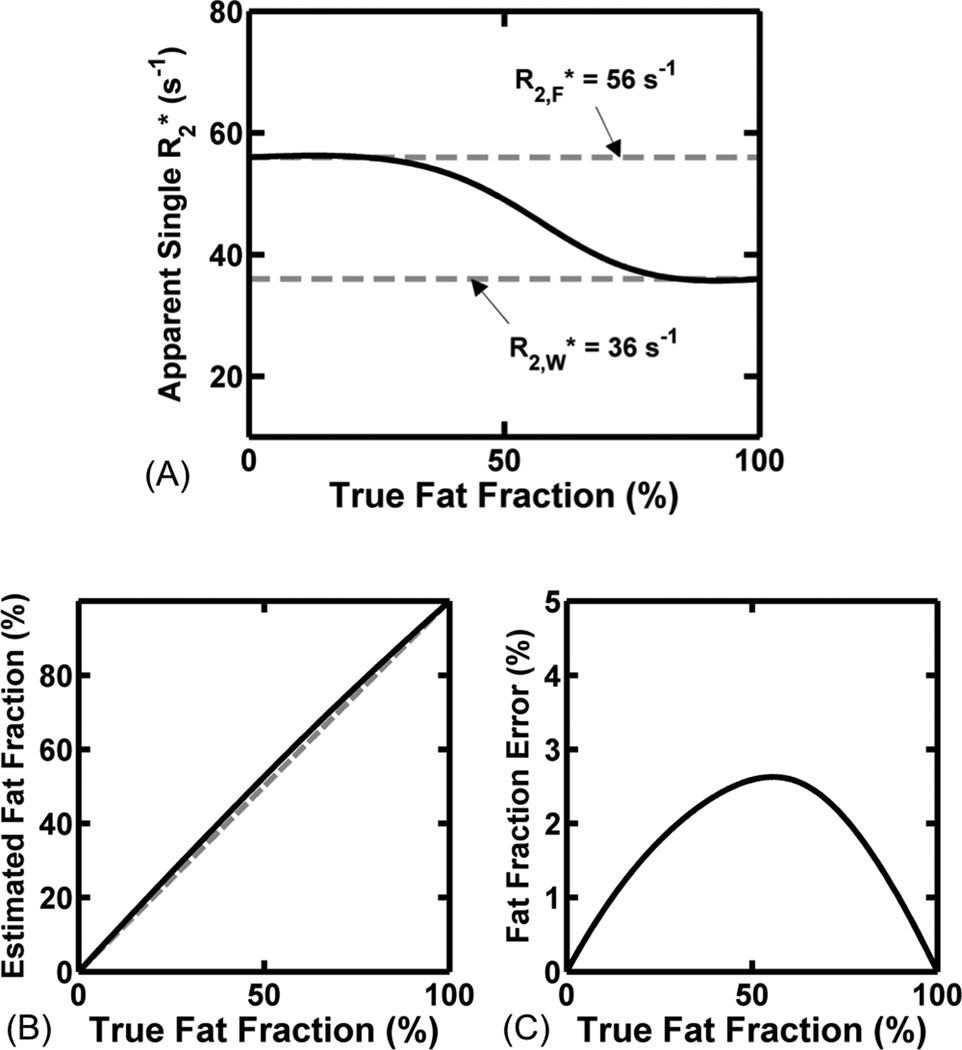

As shown in Fig. 4, the error simulation plots the apparent estimated using single- correction (Fig. 4a), as well as the apparent FF (Fig. 4b) and bias in FF estimate (Fig. 4c), plotted over a complete range of true fat-fractions (0–100%). As expected, the estimate of using the single- model (Fig. 4a) is much closer to the of water (56 s−1) at low FFs, and much closer to the of fat (36 s−1) at high FFs. In Fig. 4c, it can be seen that there is a very small bias that results in the apparent fat-fraction, resulting from the use of single- correction. The highest bias that occurs for the worst-case combination of is only 2.6%, which occurs at a true fat-fraction of 55% and is still in good agreement with recently published results (21). Of note, the bias in FF drops to 1.5%, 0.8%, and 0.4% at true fat-fractions of 20%, 10% and 5%, respectively, which are fat-fraction values more typically encountered in the liver.

Figure 4.

Even the largest differences between and that were found in our data leads to a relatively small bias in fat fraction. The apparent single- values used at different fat fractions (a.), the estimated FF using these values (b.), and the resultant FF error (c.) are shown. The ‘worst-case’ (furthest from linear fit) point was used here to estimate error ( and ).

DISCUSSION

In this work, we have evaluated the accuracy of single- vs. dual- correction for quantification of liver fat in patients imaged in a clinical setting. Although dual- modeling more accurately reflects the underlying physics and should lead to reduced bias in the estimation of fat-fraction, its poor noise performance and instability detrimentally impact its ability to quantify fat concentration accurately. Previous work in fat-water-iron phantoms led to more accurate estimates of fat concentration (20), but to our knowledge, comparison of single- and dual- correction methods in a clinical setting has not been performed. In this work we demonstrated that single- correction is more accurate than dual- correction in patients with hepatic steatosis, imaged in a clinical setting. Further, since dual- correction offers little improvement in bias and is unstable at the low fat-fractions that are frequently seen in the liver, we conclude that single- correction, rather than dual- correction, should be used for accurate quantification of fat in clinical studies.

Of the 3 reconstruction methods tested, complex, mixed, and magnitude, all performed similarly well for estimating FF with single- correction at high FF. Previously published work (24) indicates that single- correction in combination with mixed fitting performs well at low FF. Based on this evidence, as well as the theoretical considerations of eddy currents and TE combinations, mixed single- fitting is the most accurate method to use, for both low and high FF.

The noise performance of the 6 reconstruction combinations was compared by measuring the standard deviation of the FF and maps. Noise was dramatically lower using single- correction, with either complex or mixed fitting. The use of magnitude fitting, and especially dual- correction led to large increases in noise in the FF and estimates.

The use of P-values provides evidence for what kind of relationship exists between spectroscopy and FF, for each fit. P-values have been calculated for the null hypothesis that the slope m=0. Since all of these P-values are statistically significant, the conclusion here is that there is some linear relationship for all methods (y=mx+b, m≠0). Ideally, this linear relationship would be perfect correspondence (y=x). Therefore, the P-values for the slopes were then calculated for the null hypothesis m=1, and the P-values for the intercepts were calculated for the null hypothesis b=0. None of the single- fits had significant P-values for either m=1 or b=0, meaning that the hypothesis y=x cannot be rejected. However, two of the dual- fits (mixed and magnitude) did have significant P-values for both slope and intercept, so we reject the hypothesis y=x. The complex dual- fit did not have significant P-values and we cannot reject y=x; however, the large standard deviations on the slope and intercept estimates reflect the poor noise performance of this method.

Compared to single- correction, the use of dual- correction is problematic because an additional nonlinear parameter must be estimated from the same data. For this reason, dual- correction has inherently worse noise performance than single- correction (21,30). It also suffers from instability at low (or high) fat-fractions, where it is difficult to estimate (and therefore correct) of a species that is in very low concentration. Furthermore, errors in FF estimates from single- reconstructions are very small at low FF (see Fig. 4), so there is less need for dual- in that regime.

Dual- correction also appears to have much greater sensitivity to other artifacts, such as phase errors, ghosting, etc, than single- correction. Although a detailed analysis of this sensitivity is beyond the scope of this work, the instability of dual- correction with unanticipated phase errors is an additional reason to avoid dual- and use single- to measure FF from clinical data. These two factors (poor noise performance and sensitivity to artifacts) may explain the relatively worse agreement of FF from dual- modeling with spectroscopy. The apparent sensitivity of dual- correction to small phase shifts from image artifacts is consistent with the observation that dual- correction had higher accuracy when combined with mixed fitting or magnitude fitting (Fig. 2e–f). In these cases, the improvement in stability (by discarding phase information), despite the worse noise performance of both magnitude fitting and dual- correction, led to improved accuracy in comparison to complex fitting used with dual- correction.

Correlation of FF with spectroscopy measurements was slightly lower in this work compared to previously published results (7,29), even for single- correction with magnitude fitting. This difference is likely due to the restriction to patients with hepatic FF greater than 5% with no data points near the origin, which would have certainly improved correlation. This was done to avoid instability in dual- models. In fact, single- correction was recently shown to have very high correlation with spectroscopy on the same datasets examined in this work, over a complete range of fat-fractions (7,29).

Simulations that were performed to determine the bias that results from using single- correction using the “worst-case” pair of values experienced clinically, demonstrated a very small bias from using single- correction. In fact, the maximum bias of 2.6% occurred at a true fat-fraction of 56%, which is seldom experienced clinically. At more typical fat fractions (e.g. 0–20%), the bias was always less than 1.5%. To put this in perspective, this bias is smaller than the precision of chemical shift-encoded methods for fat-quantification. In a recently reported repeatability study, Hines et al reported that a 95% confidence interval of −2.70% to 2.87%, based on a single ROI measurement from fat-fraction maps (29). Thus, the degree of bias that may result from using single- correction is less than the precision of the method.

The small bias resulting from the use of single- correction is related to the small difference between and , as seen in Fig. 3a. The similarity in values of and is shown by the slope not being significantly different from 1 (p=0.78), and intercept not being significantly different from 0 (p=0.71). Since the values are so close, using a common value for both fat and water (the single- model) does not introduce a large bias.

We have used single-voxel MR spectroscopy (STEAM) as the reference standard for FF. STEAM data were quantified using a general model that makes no assumptions about the relationships between the of the different peaks. Therefore, this general spectroscopic model is a good reference to validate the assumptions made in single- and dual- modeling regarding the decay of water and fat signals.

Limitations of this work include the use of fixed acquisition parameters. For example, increasing the number of echoes beyond 6 may have resulted in improved noise performance using dual- correction. However, increasing the number of echoes increases the TR and scan time, complicating whole-liver acquisitions within a single breath-hold. Constrained models, where the difference between and is modeled before fitting, may provide dual- methods with good SNR and low bias. A simple constrained model in which the difference between and is fixed has been explored by Bydder et al (15).

An additional limitation of this work is that of the 97 patients, we did not observe any patients with simultaneous iron overload and steatosis. The presence of iron overload, which leads to increased values, may diminish the advantages of single- modeling shown in this work. In a fat-water-iron phantom study by Chebrolu et al, dual- correction with complex fitting led to improved accuracy in vials containing high concentrations of fat and iron (20). However, the particle size of fat in that study was large (approximately 250 µm), and a recent phantom study by Hines et al demonstrated that small fat particle size, mimicking intracellular vacuoles of fat, greatly decreases the relative difference in between fat and water (37). Regardless, it is difficult to conclude whether the results of this study can be extended to patients with concomitant iron overload and steatosis.

In conclusion, single- correction leads to more accurate quantification of fat-fraction in a clinical setting than dual- correction, regardless of the FF level. Further, complex fitting may lead to small, but important, biases in measured fat content due to phase errors caused by eddy currents, while magnitude fitting suffers from reduced noise performance. The use of single- correction with mixed fitting maintains good noise performance with acceptable bias, providing the most accurate chemical shift–encoded imaging approach to measure of liver fat content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Gavin Hamilton for the STEAM-MRS pulse sequence.

Grant support: The work presented in this paper was supported by the NIH (R01 DK083380, R01 DK088925, RC1 EB010384), the WARF Accelerator Program, and the Coulter Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(2):E462–E468. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00064.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Prevalence, gender, ethnic variations, and prognosis of NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(Suppl 1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeder SB, Sirlin CB. Quantification of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(3):337–357. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeder S, Hines C, Yu H, McKenzie C, Brittain J. On The Definition of Fat-Fraction for In Vivo Fat Quantification with Magnetic Resonance Imaging; In Proceedings of the 17th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; April; Honolulu: 2009. p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokoo T, Bydder M, Hamilton G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: diagnostic and fat-grading accuracy of low-flip-angle multiecho gradient-recalledecho MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology. 2009;251(1):67–76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511080666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meisamy S, Hines CD, Hamilton G, et al. Quantification of hepatic steatosis with T1-independent, T2-corrected MR imaging with spectral modeling of fat: blinded comparison with MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2011;258(3):767–775. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon WT. Simple proton spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 1984;153(1):189–194. doi: 10.1148/radiology.153.1.6089263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover GH. Multipoint Dixon technique for water and fat proton and susceptibility imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1(5):521–530. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glover GH, Schneider E. Three-point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magn Reson Med. 1991;18(2):371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernando D, Haldar JP, Sutton BP, Ma J, Kellman P, Liang ZP. Joint estimation of water/fat images and field inhomogeneity map. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(3):571–580. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeder SB, Wen Z, Yu H, et al. Multicoil Dixon chemical species separation with an iterative least-squares estimation method. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu CY, McKenzie CA, Yu H, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Fat quantification with IDEAL gradient echo imaging: correction of bias from T(1) and noise. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(2):354–364. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Brodsky E, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Multiecho water-fat separation and simultaneous R2* estimation with multifrequency fat spectrum modeling. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1122–1134. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bydder M, Yokoo T, Hamilton G, et al. Relaxation effects in the quantification of fat using gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26(3):347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, Reeder SB, Shimakawa A, Brittain JH, Pelc NJ. Field map estimation with a region growing scheme for iterative 3-point water-fat decomposition. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(4):1032–1039. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hines CD, Yu H, Shimakawa A, et al. Quantification of hepatic steatosis with 3-T MR imaging: validation in ob/ob mice. Radiology. 2010;254(1):119–128. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeder SB, Robson PM, Yu H, et al. Quantification of hepatic steatosis with MRI: the effects of accurate fat spectral modeling. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(6):1332–1339. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H, McKenzie CA, Shimakawa A, et al. Multiecho reconstruction for simultaneous water-fat decomposition and T2* estimation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(4):1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chebrolu VV, Hines CD, Yu H, et al. Independent estimation of T*2 for water and fat for improved accuracy of fat quantification. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(4):849–857. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines C, Rowland I, Roen C, et al. Validation of Imaging Biomarkers of Steatosis in ob/ob Mice with Multiple SPIO Injections; In Proceedings of the 19th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; May; Montreal: 2011. p. 742. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, Shimakawa A, Hines CD, et al. Combination of complex-based and magnitude-based multiecho water-fat separation for accurate quantification of fat-fraction. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(1):199–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu H, Shimakawa A, Hernando D, et al. Noise Performance of Magnitude-based Water-Fat Separation is Sensitive to the Echo Times; In Proceedings of the 19th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; May; Montreal: 2011. p. 2715. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernando D, Hines CD, Yu H, Reeder SB. Addressing phase errors in fat-water imaging using a mixed magnitude/complex fitting method. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):638–644. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernando D, Hines CD, Yu H, Reeder SB. Addressing phase errors in fat-water imaging using a mixed magnitude/complex fitting method. Magn Reson Med. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23044. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernando D, Liang ZP, Kellman P. Chemical shift-based water/fat separation: a comparison of signal models. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(3):811–822. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Graaf RA, Rothman DL. In vivo detection and quantification of scalar coupled H-1 NMR resonances. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance. 2001;13(1):32–76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bydder M, Shiehmorteza M, Yokoo T, et al. Assessment of liver fat quantification in the presence of iron. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28(6):767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hines CD, Frydrychowicz A, Hamilton G, et al. T(1) independent, T(2) (*) corrected chemical shift based fat-water separation with multi-peak fat spectral modeling is an accurate and precise measure of hepatic steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(4):873–881. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chebrolu VV, Yu H, Pineda AR, McKenzie CA, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Noise analysis for 3-point chemical shift-based water-fat separation with spectral modeling of fat. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(2):493–500. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frahm J, Bruhn H, Gyngell ML, Merboldt KD, Hanicke W, Sauter R. Localized high-resolution proton NMR spectroscopy using stimulated echoes: initial applications to human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;9(1):79–93. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton G, Middleton MS, Bydder M, et al. Effect of PRESS and STEAM sequences on magnetic resonance spectroscopic liver fat quantification. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(1):145–152. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton G, Yokoo T, Bydder M, et al. In vivo characterization of the liver fat (1) H MR spectrum. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(7):784–790. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanhamme L, van den Boogaart A, Van Huffel S. Improved method for accurate and efficient quantification of MRS data with use of prior knowledge. J Magn Reson. 1997;129(1):35–43. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brau AC, Beatty PJ, Skare S, Bammer R. Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and efficiency among autocalibrating data-driven parallel imaging methods. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(2):382–395. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hines C, Roen C, Hernando D, Reeder S. Effects of Fat Particle Size on R2* in Fat-Water-SPIO Emulsion Phantoms: Implications for Fat Quantification with Phantoms; In Proceedings of the 19th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; May; Montreal: 2011. p. 4514. [Google Scholar]