Abstract

Background

Family history is a risk factor for colon cancer and guidelines recommend initiating colonoscopy screening at age 40 in individuals with affected relatives. Racial differences exist in colon cancer incidence and mortality which could be related to variations in screening of increased risk individuals.

Methods

Baseline data from 41830 participants in the Southern Community Cohort Study were analyzed to determine the proportion of colonoscopy procedures in individuals with strong family histories of colon cancer, and whether differences existed based on race.

Results

In participants with multiple affected first degree relatives (FDR) or relatives diagnosed before age 50, 27.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 23.5%–31.1%) of African-Americans reported a colonoscopy within the past 5 years compared to 43.1% (37.0%–49.2%) of white participants (p-value < 0.0001). In these individuals, African-Americans had an odds ratio of 0.51 (0.38–0.68) of having undergone recommended screening procedures compared to white participants after adjusting for age, gender, education, income, insurance status, total number of FDR, and time since last medical visit. African-Americans reporting multiple affected first degree relatives or relatives diagnosed before age 50, who had ever undergone endoscopy were less likely to report a personal history of colon polyps (OR = 0.29; 0.20–0.42) when compared to whites with similar family histories.

Conclusions

African-Americans with first-degree relatives affected with colon cancer are less likely to undergo colonoscopy screening compared to whites with affected relatives. Increased efforts need to be directed at identifying and managing underserved populations who might be at increased risk for colon cancer based on their family history.

Introduction

Family history is an important risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC) with one’s risk increasing as the burden of disease within a family increases.1 For individuals with a first-degree relative (FDR) diagnosed with colon cancer prior to the age of 60, or who have multiple FDR affected, the cumulative risk of CRC is sufficiently increased to warrant aggressive screening.2 Subsequently, most clinical guidelines have recommended initiating CRC screening at age 40, as opposed to the age of 50, the recommended age to begin screening in average risk individuals.3, 4 Additionally, for increased risk patients without a hereditary CRC syndrome, screening recommendations have explicitly advocated colonoscopy as the screening modality of choice, with screening intervals suggested for every 5 years.

Despite effective interventions for CRC prevention, colon cancer is associated with significant differences in mortality among ethnic groups.5, 6 For example; African-Americans have a higher incidence and mortality associated with CRC when compared to whites. It is possible that factors associated with the delivery of cancer prevention services may contribute to these differences. Several studies have evaluated differences in CRC screening rates between average risk African-Americans and whites. Although some studies have identified significant differences, many have found similar screening rates after adjusting for socioeconomic factors.7–11 Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether CRC screening differences might exist in individuals at increased risk for colon cancer, such as those with a positive family history.

Because of the increased risk of CRC associated with a family history, even small screening inequities in individuals with affected relatives could translate into larger differences in cancer outcomes.6 The purpose of this study was to determine whether racial differences exist between the use of colonoscopy procedures in increased risk individuals.

Methods

Study Population

The Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) is an ongoing prospective cohort study investigating cancer incidence and mortality disparities across racial and urban/rural groups in a population of participants enrolled at community health centers (CHCs) and through general-population sampling (via the mail) in a 12-state region throughout the southeast.12 Included within this cross-sectional analysis are participants enrolled from 48 CHCs from 2002–2006. Potential study subjects were approached by a trained interviewer and were informed of the study. Participants were eligible if they were aged 40 to 79 years, English-speaking, and not undergoing treatment for any cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) over the preceding 12 months. SCCS is approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Meharry Medical College Institutional Review Boards.

Among 51,454 participants, we excluded 2,546 individuals who were self-identified as a race other than African-American or white. These groups were excluded due to a lack of power to perform the study in other racial groups. We also excluded 469 participants whose sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy use could not be determined and 6,609 participants who could not be classified with certainty according to family history of colon cancer, leaving us with 41,830 participants. Baseline data were collected for demographics, family cancer history, tobacco and alcohol use, prior medical history, physical activity and prescription medications.

Family History and Endoscopy Assessment

Family history information was collected for FDR exclusively. Individuals reporting a FDR with colon cancer were asked: 1) the number of affected relatives and 2) if the age of diagnosis occurred prior to the affected relatives 50th birthday. Because of possible etiological differences between colon and rectal cancers, we only included individuals reporting a family history of colon cancer. Participants were then categorized into three groups based on their self-reported family history. These categories were based on modified screening categories proposed by the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA)4 and included: 1) multiple affected FDR or a FDR diagnosed before 50? years of age; 2) a single first degree relative diagnosed after the age of 50? years; and 3) no family history. Because the SCCS only recorded age at cancer diagnosis as a dichotomous variable (< 50 years versus ≥ 50 years), we used this age as our indicator of increased familial risk rather than the AGA specified age of 60? years.

Participants were asked questions regarding past history of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy procedures. A sigmoidoscopy was described as “[a] short tube inserted into the rectum while you are awake and un-sedated to look for colon or rectal cancer” and a colonoscopy was described as “[a] long tube inserted into rectum after you are sedated or put to sleep to look for colon or rectal cancer.” We compared the proportion of individuals reporting a colonoscopy procedure within the prior 5 years among individuals in different family history categories. For our primary analysis, we used the most conservative screening recommendation with colonoscopy screening beginning at age 40 years and being repeated every 5 years. We repeated our analysis using the less stringent recommendations suggested for individuals with a single FDR affected after the age of 60 and compared the proportion of participants that reported either a colonoscopy within the prior 10 years or a flexible sigmoidoscopy within the prior 5 years.4 The baseline survey did not inquire about the use of fecal occult blood testing and barium enema.

Statistical Analysis

For descriptive univariate analyses, continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance. Categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-square test. To determine the impact of race on colonoscopy procedure rates, we constructed logistic regression models adjusted for age (continuous), gender (male versus female), educational status (high school or less versus beyond high school), insurance status (any private, only public/other, or none), income level (< $15,000 per year versus $15,000 or greater per year), total number of FDR reported (continuous), and time (in months) since last visit to a doctor or other medical person. The models were then stratified based on family history. We constructed logistic regression models to determine the association of race to self-reported personal history of colon or rectal polyps stratified by family history. In this model, we adjusted for age, gender, educational status, total number of FDR, body-mass index (continuous), current tobacco use (yes, no), alcohol use (≥ 2 drinks per day vs < 2 drinks per day), physical activity level defined as the estimated total MET-hrs per day from work and sports activities (continuous), daily calcium supplement use (yes, no), daily folate supplementation (yes, no), regular use of regular aspirin (yes, no) and time since last visit to a doctor or other medical person. Because of the possibility of intra-health center correlations regarding colon cancer screening practices, we constructed Generalized Estimating Equations to adjust for any clustering by community health center. All analyses had a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.1 software.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. African-American participants were younger than white participants (mean age 50.6 versus 52.6, p-value < 0.0001). African-American respondents were less likely to have been educated beyond high school (27.4% versus 30.6%, p-value < 0.0001), and less likely to have a household income of $15,000 or greater (38.5% versus 41.7%, p-value < 0.0001) when compared to white participants. Five hundred and thirty-eight (1.7%) African-American respondents reported multiple affected FDR or a FDR diagnosed prior to age 50 years compared to two hundred and fifty-five (2.7%) white respondents (p-value < 0.0001). African-Americans were similarly less likely to report a single affected relative diagnosed after the age of 50 years (4.0% versus 5.3%, p-value <0.0001). African-Americans were less likely to have a personal history of colon cancer when compared to whites (0.2% versus 0.5% p-value < 0.0001) and also less likely to report a personal history of colon or rectal polyps (3.6% versus 10.8%, p-value <0.0001).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics Stratified by Race

| Characteristic | African- American (N = 32265) |

White (N = 9565) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean in years | 50.6 ± 8.4 | 52.6 ± 9.2 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, N (%) female | 19106 (59.2) | 6458 (67.5) | <0.0001 |

| Income, N (%) > $15,000 | 12297 (38.5) | 3949 (41.7) | <0.0001 |

| Education, N (%) Education beyond high school Insurance Status, |

8829 (27.4) | 2922 (30.6) | <0.0001 |

| N (%) Any Private Insurance | 6957 (21.6) | 2042 (21.4) | 0.42 |

| N (%) Medicaid, Medicare, | 11279 (35.0) | 3294 (34.5). | |

| CHAMPUS/Tricare, or Other | |||

| N (%) None | 13985 (43.4) | 4219 (44.2) | |

| Body Mass Index, mean in kg/m2 | 30.3 ± 7.5 | 30.1 ±7.7 | 0.03 |

| Smoking Status, N (%) current | 14541 (45.1) | 4166 (43.6) | 0.009 |

| Alcohol Use, N (%) Using ≥ 2 drinks per day | 6033 (18.8) | 929 (9.8) | <0.0001 |

| Physical Activity Level, mean in MET-hrs/day | 23.4 ± 19.5 | 21.2 ± 18.4 | <0.0001 |

| Personal History of Colon Cancer, N (%) yes | 68 (0.2) | 49 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| Age Diagnosed with Colon Cancer, mean in years | 47.3 ± 12.1 | 51.9 ± 11.2 | 0.04 |

| Personal History of Colorectal Polyps, N (%) yes | 1170 (3.6) | 1033 (10.8) | <0.0001 |

| Age First Diagnosed with Polyp, mean in years | 49.3 ± 12.1 | 49.1 ± 12.6 | 0.69 |

| Total Number of First Degree Relatives, mean | 7.1 ± 3.8 | 5.5 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 |

| Family History Group | |||

| 2 or More FDR Diagnosed at Any Age or1 FDR Diagnosed < 50 years, |

538 (1.7) | 255 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| 1 FDR Diagnosed at 50 years or Greater | 1294 (4.0) | 504 (5.3) | |

| Regular* Use of Regular Aspirin, N (%) yes | 3771 (11.7) | 1483 (15.5) | <0.0001 |

| Daily Use of Calcium, N (%) yes | 2102 (6.5) | 1328 (13.9) | <0.0001 |

| Daily Use of Folate, N (%) yes | 991 (3.1) | 472 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Last Visit to a Healthcare Provider, mean in months, |

7.3 ± 22.3 | 6.2 ± 20.6 | <0.0001 |

Regular use defined as: at least two times per week, for one month or more.

Multiple First-Degree Relatives or Single Relative Diagnosed Before 50 Years of Age

In participants aged 40 to 49 years, 21.0% of African-Americans reported undergoing a colonoscopy within the prior 5 years compared to 34.0% of whites (p-value = 0.009) (Table 2). In this same age group, 11.2 % of African-Americans reported undergoing a flexible sigmoidoscopy within the past 5 years compared to 9.4% of whites (p-value = 0.60). African-Americans had an adjusted odds ratio of 0.52 (0.32–0.84) when compared to whites for reporting having undergone a colonoscopy within the prior 5 years. (Table 3)

Table 2.

Proportions of Participants Reporting Prior History of Colonoscopy or Sigmoidoscopy by Family History

| < 50 years | ≥ 50 years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African- American N (%) |

White N (%) |

P-value | African- American N (%) |

White N (%) |

P-value | |

| Colonoscopy in past 5 years |

||||||

| > 1 FDR or 1 FDR <50 |

58 (21.0) | 36 (34.0) | 0.009 | 88 (34.0) | 73 (49.7) | 0.002 |

| 1 FDR ≥ 50 | 75 (13.5) | 41 (24.6) | 0.0007 | 239 (32.5) | 136 (40.5) | 0.01 |

| No FDR | 1289 (7.9) | 492 (12.4) | <0.0001 | 3102 (22.1) | 1445 (30.1) | <0.0001 |

| Colonoscopy in past 10 years |

||||||

| > 1 FDR or 1 FDR <50 |

67 (24.3) | 46 (43.4) | 0.0002 | 93 (35.9) | 84 (57.1) | <0.0001 |

| 1 FDR ≥ 50 | 78 (14.1) | 46 (27.5) | <0.0001 | 259 (35.2) | 152 (45.2) | 0.002 |

| No FDR | 1438 (8.8) | 587 (14.8) | <0.0001 | 3338 (23.8) | 1632 (34.0) | <0.0001 |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy in past 5 years |

||||||

| > 1 FDR or 1 FDR <50 |

31 (11.2) | 10 (9.4) | 0.60 | 44 (16.9) | 25 (17.2) | 0.93 |

| 1 FDR ≥ 50 | 50 (9.0) | 14 (8.4) | 0.82 | 115 (15.7) | 51 (15.2) | 0.85 |

| No FDR | 996 (6.1) | 225 (5.7) | 0.29 | 2041 (14.6) | 587 (12.2) | <0.0001 |

FDR = First Degree Relative

Table 3.

Colorectal cancer screening stratified by colon cancer family history*

| FDR < 50 or multiple FDR (N = 793) |

Single FDR ≥ 50 (N = 1798) |

No family history (N = 39239) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | |||

| Colonoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.51 (0.38–0.68) | 0.75 (0.58–0.96) | 0.68 (0.60–0.77) |

| P-value | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Colonoscopy in prior 10 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.41 (0.30–0.54) | 0.70 (0.53–0.93) | 0.66 (0.60–0.73) |

| P-value | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Sigmoidoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.09 (0.66–1.81) | 1.07 (0.67–1.73) | 1.22 (1.10–1.34) |

| P-value | 0.74 | 0.77 | <0.0001 |

| Participants ages 40 to 49 years | |||

| Colonoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | 0.41 (0.27–0.62) | 0.60 (0.49–0.75) |

| P-value | 0.008 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Colonoscopy in prior 10 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.42 (0.27–0.65) | 0.39 (0.25–0.60) | 0.57 (0.47–0.69) |

| P-value | 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Sigmoidoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.10 (0.46–2.65) | 1.08 (0.54–2.16) | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) |

| P-value | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.26 |

| Participants ages ≥ 50 years | |||

| Colonoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.50 (0.34–0.74) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | 0.81 (0.76–0.88) |

| P-value | 0.0005 | 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Colonoscopy in prior 10 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.41 (0.26–0.62) | 0.80 (0.58–1.10) | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) |

| P-value | <0.0001 | 0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Sigmoidoscopy in prior 5 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.01 (0.56–1.81) | 1.07 (0.66–1.74) | 1.27 (1.13–1.44) |

| P-value | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.0001 |

Adjusted for the listed covariates and age, gender, educational status, insurance status, income, total number of first degree relatives (FDR), and time since last medical visit

For participants 50 years or older, African-Americans with a strong family history were also less likely to report having undergone colonoscopy screening within the prior 5 years compared to whites with similar family histories (34.0% versus 49.7%, p-value = 0.002). There was no difference in reported rates of flexible sigmoidoscopy procedures between these two groups (16.9% versus 17.2%, p-value = 0.93). African-Americans 50 years or older had an adjusted odds ratio of 0.50 (0.34–0.74) when compared to whites for reporting having undergone a colonoscopy within the prior 5 years. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Personal history of a colon polyp in participants reporting ever undergoing a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy *

| FDR < 50 or multiple FDR (N = 349) |

Single FDR ≥ 50 (N = 690) |

No family history (N = 10205) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.29 (0.20–0.42) | 0.40 (0.28–0.59) | 0.45 (0.39–0.52) |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Participants ages 40 to 49 years | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.22 (0.09–0.53) | 0.16 (0.06–0.42) | 0.39 (0.29–0.51) |

| P-value | 0.0006 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| Participants ages 50 years or above | |||

| Race, white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 0.28 (0.18–0.43) | 0.50 (0.33–0.75) | 0.46 (0.40–0.53) |

| P-value | < 0.0001 | 0.0008 | <0.0001 |

Adjusted for the listed covariates as well as age (continuous), gender, educational status, total number of first degree relatives (FDR), body mass index, tobacco use, alcohol use, physical activity level, calcium use, folate use, regular aspirin use, and time since last medical visit.

Single First Degree Relative Diagnosed at 50 years of Age or Older

For participants aged 40 to 49 years, 13.5% of African-Americans reported having undergone a colonoscopy in the past 5 years compared to 24.6% of white respondents (p-value 0.0007). There was no difference in the reported rate of flexible sigmoidoscopy procedures between African-Americans and whites (9.0% versus 8.4%, p-value = 0.82). African-Americans had an adjusted odds of 0.41 (0.27–0.62) of having completed a colonoscopy procedure in the prior 5 years when compared to whites (Table 3).

In participants aged 50 or above, 32.5% of African-Americans versus 40.5% of whites reported a colonoscopy in the past 5 years (p-value = 0.01). Rates of flexible sigmoidoscopy were similar between African-Americans and whites in these age groups (15.7% versus 15.2%, p-value = 0.85).

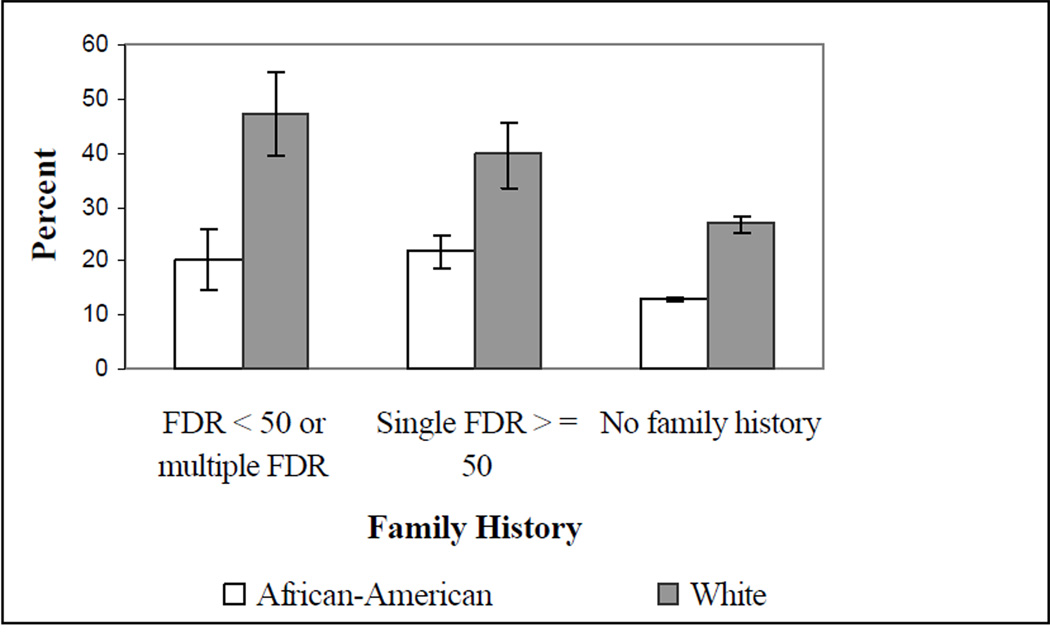

Personal History of Colon or Rectal Polyps

We investigated the relationship between family history and colorectal polyp diagnoses in all participants who reported a prior colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy. (Figure 1) (Harvey – you’ll need to re-do Figure 1 with the new numbers.) African-Americans with multiple FDR or a single FDR diagnosed with colon cancer before age 50 were less likely to report a personal diagnosis of colorectal polyps when compared to white respondents with similar family histories (19.7% versus 46.9%, p-value < 0.0001). After multivariate adjustment, African-Americans with strong family histories of colon cancer had an odds of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.20–0.42) of reporting a personal diagnosis of colorectal polyps when compared to white respondents. (Table 4)

Figure 1.

Self-reported polyp history in participants reporting ever undergoing a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy*

*For each family history category the difference between African-Americans and whites reporting a personal history of colon polyps was statistically significant at a P-value < 0.0001

In participants reporting a single affected relative diagnosed at 50 years or older, African-Americans were also less likely to report a personal diagnosis of colorectal polyps when compared to white respondents (21.3% versus 40.4%, p-value < 0.0001). African-Americans had an adjusted odds ratio of 0.40 (95% CI: 0.28–0.59) of reporting a personal diagnosis of colorectal polyps when compared to whites. (Table 4)

Reported Reasons for Not Undergoing Colonoscopy or Sigmoidoscopy

We compared reported reasons for not undergoing colonoscopy screening between African-Americans and whites (Table 5). In subjects with any family history of colon cancer, African-American were more likely to report that they had not been recommended to undergo the procedure by their provider when compared to white (59.3% versus 51.0%, p-value = 0.003). African-Americans with a family history of colon cancer were less likely to report procedure cost and embarrassment as reasons for not undergoing screening.

Table 5.

Reasons for not undergoing colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy in participants without prior endoscopic procedures

| One or More Affected First Degree Relatives |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | African- American N (%) |

White N (%) |

P-value |

| Not recommended by MD | 738 (59.3) | 227 (51.0) | 0.003 |

| Cost | 113 (9.1) | 77 (17.3) | <0.0001 |

| Discomfort | 45 (3.6) | 25 (5.6) | 0.07 |

| Fear | 54 (4.3) | 24 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Embarrassment | 11 (0.9) | 10 (2.3) | 0.03 |

| Forgot | 36 (2.9) | 4 (0.9) | 0.02 |

| No reason given | 238 (19.1) | 96 (21.6) | 0.26 |

|

No Family History of Colon Cancer |

|||

| Not recommended by MD | 15268 (63.3) | 4104 (63.3) | 0.99 |

| Cost | 1812 (7.5) | 877 (13.5) | <0.0001 |

| Discomfort | 767 (3.2) | 303 (4.7) | <0.0001 |

| Fear | 684 (2.8) | 159 (2.5) | 0.09 |

| Embarrassment | 235 (1.0) | 121 (1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Forgot | 413 (1.7) | 94 (1.5) | 0.14 |

| No reason given | 5370 (22.3) | 1171 (18.1) | <0.0001 |

Discussion

In this large, cross-sectional analysis we found low rates of colonoscopy procedures in individuals with strong family histories for colon cancer with less than one-third (revise) of increased risk individuals having undergone the recommended screening. African-Americans with multiple affected FDRs were half as likely to have undergone recommended screening procedures when compared to whites, even after adjusting for education, income, and insurance status. For both African-Americans and whites with family histories of colon cancer, the most common reason given for not having had a colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy was a lack of recommendations from their healthcare provider and this reason was more commonly reported by African-Americans.

Recommendations regarding CRC screening practices in individuals with family histories have been quite consistent. The AGA and American College of Gastroenterology,4 American Cancer Society (ACS),3, 13 The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons,14 American Society of Clinical Oncology,15 and National Comprehensive Cancer Network 16 all advise colonoscopy screening beginning at age 40 years or 10 years prior to the earliest cancer in the family with follow-up intervals every 5 years. The United States Preventive Services Task Force has not been as specific and describes the early initiation of CRC screening in patients with a FDR diagnosed before the age of 60 years as a “reasonable” strategy.17 Notably, although family history has been a consistent factor influencing CRC screening decisions, recently the American College of Gastroenterology has proposed modifying the age at which to begin screening in African-Americans from 50 years to 45 years.18 These recommendations stem from consistent findings indicating African-Americans tend to be diagnosed at earlier ages than whites.6, 19 Although crudely we found African-Americans to report earlier ages for colon cancer diagnoses when compared to whites (p-value = 0.04), after adjusting for age at the time of the interview, we found no significant difference by race (p-value = 0.78). (Harvey – remember that the Whites in the study population are older than the Blacks. Without adjusting for this difference, this can create the impression that Blacks were diagnosed at earlier ages.)

Few prior studies have examined CRC screening rates in individuals with positive family histories. A study by Fletcher et al. which surveyed 1,870 patients 35 to 55 years of age found that only 45% of individuals under the age of 50 with a strong family history of CRC had been screened.20 Factors contributing to the discrepancies in screening rates between this paper and ours are likely secondary to patient demographics. In the Fletcher study, over 80% of the sample reported a household income of $50,000 or greater and 77% had a college degree. In the SCCS only 4% of respondents reported an income at this level with only 9% having completed college. Another study using data collected as part of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) suggested that African-Americans with family histories for CRC were undergoing colonoscopy screening at significantly lower rates than whites, however this study was limited by a small sample of African-American respondents with positive family histories (n = 35).21

We did find that African-Americans were more likely to report not being recommended for the procedures when compared to whites. However, it is unlikely that this difference completely explains the variation in the rate of colonoscopy procedures. There are likely patient specific factors that impact how family history information is integrated into patient care. A prior study reported that African-Americans with a positive family history of CRC were less likely to perceive themselves at increased risks for cancer when compared to white individuals with positive family histories (36.5% versus 82.5%, p-value = 0.004).21 Bastani et al similarly found that African-Americans with a family history of CRC tended to be less likely to perceive themselves as at increased risk when compared to whites.22

Having a family history of CRC is a risk factor for adenomatous polyps.23, 24 Our study demonstrated a similar finding, with higher rates of personal diagnoses of colorectal polyps in individuals with family histories of colon cancer. In our study, polyps were identified by self-report, thus one potential explanation for our finding of fewer personal diagnoses of colon polyps in African-Americans may be related to reporting bias. However, a study which examined Medicare claims data on approximately 1.8 million colonoscopy procedures similarly noted a lower rate of polyp detection in African-Americans versus whites.25

If African-Americans are less likely to have polyps detected on colonoscopy compared to whites this may be related to two possible mechanisms. Biologically, African-Americans could have fewer polyps overall yet a greater proportion of polyps which proceed to malignancies. This mechanism could reconcile a lower polyp rate with an increased cancer incidence. Another mechanism may be related to racial differences in colonoscopy miss rates. A recent systematic review reported that colonoscopy miss rates increases with decreasing polyp size;26 and other studies have suggested that right-sided lesions may also be more likely to be missed on colonoscopy examination.27, 28 When compared to a referent standard of virtual colonoscopy, optical colonoscopy predominately missed sessile, as opposed to pedunculated, adenomas.29 These findings are relevant as right-sided lesions are more common in African-Americans as opposed to whites.30, 31 Ozick et al found in a retrospective review of 179 polypectomies in African-Americans that right-sided lesions were also less likely to be pedunculated and smaller than left sided lesions and although the right-sided lesions were smaller, they were just as likely to have villous histology as left side lesions.32 Thus it is plausible that race specific adenoma characteristics may increase the likelihood of missing an adenoma at colonoscopy; however this hypothesis would have to be rigorously evaluated.

The study has several limitations worth noting. First, family history was self-reported, nevertheless; studies have suggested that self-reported family colon cancer history is moderately accurate for FDR.33 The SCCS assessed information on FDR with colon cancer and thus some subjects with multiple second degree relatives diagnosed with colon cancer or a FDR with adenomatous polyps may have been classified as having no family history rather than being at elevated risk, but we chose to focus our analysis on occurrences of cancer in FDRs. Because age at cancer diagnosis was dichotomized at 50 years rather than 60 years, our categorizations do not completely match the recommendation put forth by the AGA. This may have the consequence of misclassifying an individual with a single FDR who was diagnosed at age 55 years into the less intensive screening strategy group. Additionally, there are several limitations related to the colon cancer screening variables. For one, procedures were all self-reported; and prior studies have suggested that patient self-report may overestimate screening rates.34, 35 Secondly, the SCCS did not collect information regarding fecal occult blood testing and barium enema as colon cancer screening modalities. Although these screening procedures may have a role in individuals with a single affected relative diagnosed after the age of 60 years, most organizations recommend colonoscopy screening as the modality of choice for individuals with multiple affected relatives or relatives affected at an early age. Finally, it is not well known how accurate individuals can report a self-diagnosis of adenomas. Reporting bias may have been an important factor in the different rates of personal histories of colorectal polyps; however these results remained significant even after adjusting for education level.

In conclusion, in this disadvantaged population, the overall rate of colonoscopy procedures in individuals with family histories was low (Harvey – different interpretation with new numbers?). African-Americans with a family history are significantly less likely to have undergone colonoscopy, and are less likely to report a personal history of colorectal polyps, than whites with similar family histories. African-Americans with family histories of colon cancer who had not undergone endoscopy procedures were more likely to report a lack of provider recommendations as contributing. Providers need to elicit family history information on all patients and insure that African-Americans with affected relatives appropriately receive colon cancer screening.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: K07CA114029 (PI: Harvey J. Murff); CA092447 (PI: William J. Blot)

References

- 1.Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Oct;96(10):2992–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butterworth AS, Higgins JP, Pharoah P. Relative and absolute risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with a family history: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Jan;42(2):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006 Jan-Feb;56(1):11–25. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.1.11. quiz 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003 Feb;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Sep 23;162(17):1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer and race: understanding the differences in outcomes between African Americans and whites. Med Clin North Am. 2005 Jul;89(4):771–793. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coughlin SS, Thompson TD, Seeff L, Richards T, Stallings F. Breast, cervical, and colorectal carcinoma screening in a demographically defined region of the southern U.S. Cancer. 2002 Nov 15;95(10):2211–2222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemon S, Zapka J, Puleo E, Luckmann R, Chasan-Taber L. Colorectal cancer screening participation: comparisons with mammography and prostate-specific antigen screening. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1264–1272. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Ness RM, Dittus RS. Colorectal cancer screening among men and women in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007 Jan-Feb;16(1):57–65. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schenck AP, Klabunde CN, Davis WW. Racial differences in colorectal cancer test use by Medicare consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Apr;30(4):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult US population. Cancer. 2004 May 15;100(10):2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Steinwandel MD, et al. Southern community cohort study: establishing a cohort to investigate health disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Jul;97(7):972–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. Also: update 2001--testing for early lung cancer detection. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(1):38–75. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.38. quiz 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko C, Hyman NH. Practice parameter for the detection of colorectal neoplasms: an interim report (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 Mar;49(3):299–301. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desch CE, Benson AB, 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Nov 20;23(33):8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colorectal Cancer Screening. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines in Oncology-v.1.2007. http://www.nccn.org/

- 17.Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Jul 16;137(2):129–131. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani MS, et al. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Mar;100(3):515–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41829.x. discussion 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessup JM, McGinnis LS, Steele GD, Jr, Menck HR, Winchester DP. The National Cancer Data Base. Report on colon cancer. Cancer. 1996 Aug 15;78(4):918–926. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960815)78:4<918::AID-CNCR32>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher RH, Lobb R, Bauer MR, et al. Screening patients with a family history of colorectal cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Apr;22(4):508–513. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murff HJ, Peterson NB, Greevy RA, Shrubsole MJ, Zheng W. Early Initiation of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Individuals with Affected First-degree Relatives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jan;22(1):121–126. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0115-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bastani R, Gallardo NV, Maxwell AE. Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Ethnically Diverse High- and Average-Risk Individuals. J Psych Onc. 2001;19(3/4):65–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazzoli F, Fossi S, Sottili S, et al. The risk of adenomatous polyps in asymptomatic first-degree relatives of persons with colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995 Sep;109(3):783–788. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillem JG, Forde KA, Treat MR, Neugut AI, O'Toole KM, Diamond BE. Colonoscopic screening for neoplasms in asymptomatic first-degree relatives of colon cancer patients. A controlled, prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992 Jun;35(6):523–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02050530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper GS, Chak A, Koroukian S. The polyp detection rate of colonoscopy: a national study of Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2005 Dec;118(12):1413. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Feb;101(2):343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He J, Rabeneck L. Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):452–456. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rex DK, Rahmani EY, Haseman JH, Lemmel GT, Kaster S, Buckley JS. Relative sensitivity of colonoscopy and barium enema for detection of colorectal cancer in clinical practice. Gastroenterology. 1997 Jan;112(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickhardt PJ, Nugent PA, Mysliwiec PA, Choi JR, Schindler WR. Location of adenomas missed by optical colonoscopy. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Sep 7;141(5):352–359. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-5-200409070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson H, Jr, Margolis I, Wise L. Site-specific distribution of large-bowel adenomatous polyps. Emphasis on ethnic differences. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988 Apr;31(4):258–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02554356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odelowo OO, Hoque M, Begum R, Islam KK, Smoot DT. Colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. J Assoc Acad Minor Phys. 2002 Jul;13(3):66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozick LA, Jacob L, Donelson SS, Agarwal SK, Freeman HP. Distribution of adenomatous polyps in African-Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995 May;90(5):758–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. Jama. 2004 Sep 22;292(12):1480–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Apr 7;85(7):566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiatt RA, Perez-Stable EJ, Quesenberry C, Jr, Sabogal F, Otero-Sabogal R, McPhee SJ. Agreement between self-reported early cancer detection practices and medical audits among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white health plan members in northern California. Prev Med. 1995 May;24(3):278–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]