Abstract

We evaluated the impact of busulfan dose-intensity in patients undergoing reduced toxicity/intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation in a multicenter retrospective study of 112 consecutive patients. Seventy-five patients were conditioned with busulfan (0.8 mg/kg/dose IV × 8 doses), fludarabine (30mg/m2/day, days −7 to −3), and 6mg/kg of ATG (RIC group), while 37 patients received a more-intense conditioning with busulfan (130mg/m2/day IV, days −6 to −3), fludarabine (40mg/m2/day, days −6 to −3), and 6mg/kg of ATG (RTC group). At baseline both groups were matched for median age, unrelated donor allografts, and HLA-mismatched allografts. More patients in RIC group had high-risk disease, and higher median co-morbidity index. There were no graft rejections. Median time to neutrophil (17 vs. 15 days; p=0.003) and platelet engraftment (16 vs. 11 days; p<0.001) was significantly longer in the RIC group. RTC group had significantly more bacterial (62.2% vs. 32%; p=0.004) and fungal infections (13.5% vs. 1.3% p=0.01). For RIC and RTC groups rates of grade II-IV acute GVHD (34% vs. 40%; p-value=0.54), and chronic GVHD (45% vs. 57%; p-value=0.30) were not significantly different. In similar order at 1-year the cumulative-incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) (12% vs. 21%; p-value=0.21) and relapse rates (38% vs. 39%; p=0.96) were not significantly different. Patients in RIC and RTC groups had similar 1-year overall survival (61% vs. 50% p=0.11) and progression free survival (50% vs. 36% p-value=0.39). Our data suggest that merits of higher busulfan dose-intensity in the context of fludarabine/busulfan-based RTC may be offset by higher early morbidity.

Keywords: Fludarabine, busulfan, thymoglobulin, busulfan dose, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, graft-versus-host disease

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a potentially curative modality for a variety of hematological malignancies (1,2). However the high rates of procedure-related toxicities and non relapse mortality (NRM) have limited the applicability of HCT following myeloablative conditioning to a select cohort of younger patients with few or no medical comorbidities (3,4). The development of novel conditioning regimens with reduced intensity and/or toxicity over the last decade have undoubtedly extended the availability of allogeneic HCT to older patients and to those with significant medical comorbidities precluding use of conventional myeloablative regimens. However the intensities of these (newer) conditioning regimens vary significantly (5) from preparative regimens which are truly non-myeloablative (NMA) (6–9) on one hand, to others that are clearly myeloablative but associated with reduced toxicity (reduced toxicity conditioning [RTC] regimens) on the other hand (10,11), along with a variety of regimens with intensities intermediate between these two extremes (reduced intensity conditioning [RIC] regimens) (12–15). The potential benefit of regimens with higher dose intensities within this spectrum is (possibly) lower disease relapse rates post HCT, while the regimens with lower dose intensity (e.g. NMA regimens) are probably associated with improved NRM rates. However the conditioning regimen with best risk-benefit ratio in terms of relapse and NRM rates remains a matter of controversy.

Fludarabine is widely used in conditioning regimens for allogeneic HCT combined with intravenous busulfan (ranging in total doses of 3.2 to 12.8 mg/kg) (10,12,16). While a few retrospective studies have compared outcomes of busulfan containing RIC regimens with conventional myeloablative regimens (e.g. busulfan/cyclophosphamide 2) (16), the relative importance of busulfan’s dose intensity within the spectrum of RTC and RIC regimens merits further investigation. We report here the transplantation outcomes of patients undergoing allogeneic HCT following fludarabine, busulfan-based RTC and compare their outcomes relative to the busulfan dose received.

Patients and Methods

Patient population

One hundred and twelve consecutive patients with hematological malignancies undergoing allogeneic HCT following fludarabine, busulfan-based RIC or RTC between July 2007 and July 2010 at Ohio State University (OSU) or West Virginia University (WVU), were included. All patients had adverse-risk (precluding the use of myeloablative conditioning) that was defined by the presence of at least one of the following features: (i) age >50-years; (ii) Karnofsky performance score (KPS) ≤70; (iii) hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index (HCT-CI) >2 (17); (iv) baseline diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL); and (v) prior history of autologous transplantation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Clinical Scientific Review Committee at each institution.

Conditioning regimen

The patients undergoing HCT at OSU (n=75) received uniform RIC with fludarabine 30 mg/m2 intravenously on days −7 to −3 (total dose; 150 mg/m2), intravenous busulfan (Busulfex®, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Rockville, MD) 0.8 mg/kg/dose × 8 doses, on days −4 to −3 (total dose; 6.4 mg/kg) and thymoglobulin (ATG) (Thymoglobulin®, Genzyme; Cambridge, MA) at 2.0 mg/kg/day, on days −4 to −2 (total dose; 6 mg/kg) (RIC-group) as described previously (12,14). While the cohort undergoing transplantation at WVU (n=37) received RTC uniformly with intravenous fludarabine 40 mg/m2 intravenously on days −6 to −3 (total dose; 160 mg/m2), intravenous busulfan 130 mg/m2/day on days −6 to −3 (roughly equivalent to 12.8 mg/kg total dose) and thymoglobulin at 2.0 mg/kg/day, on days −3 to −1 (total dose; 6 mg/kg) (RTC-group) (10).

HLA typing and chimerism analysis

For each donor-recipient pair, high-resolution tissue typing was performed for HLA class-I (HLA-A,-B, -C) and class-II alleles (HLA-DRB1, -DQB1) by polymerase chain reaction- sequence specific primer (PCR-SSP) amplification from genomic DNA as described previously (18). To assess donor-cell chimerism, peripheral blood samples were collected before transplantation to identify PCR-short tandem repeat informative fragments for each donor/recipient pair. After transplantation chimerism analysis was performed on days +30, +90, +180 and +360. Complete donor chimerism was defined as presence of ≥95% of donor cells. Primary graft rejection was defined as failure to establish hematopoietic reconstitution of donor-origin post-allografting, while secondary graft rejection was defined as confirmed loss of donor cells after initial donor-origin hematopoiesis.

GVHD prophylaxis

All patients in RIC-group received standard prophylaxis of GVHD with tacrolimus (0.03 mg/kg/day IV, commencing on day −2) and mini-dose methotrexate (5 mg/m2 on days +1, +3, +6 and +11) as previously described (19). Patients in the RTC-group instead of mini-dose methotrexate received prophylaxis with mycophenolate mofetil (15 mg/kg, orally twice a day starting on day −1). Blood levels of tacrolimus were monitored weekly until day +90 to maintain levels between 5–15ng/ml. From day +90 onwards tacrolimus was tapered at the discretion of the treating physician if no GVHD appeared.

Transplantation procedure and supportive care

All patients were treated in HEPA-filtered rooms, and received fungal (fluconazole, or posaconazole), herpes zoster/herpes simplex (acyclovir or valacyclovir), bacterial and Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or dapsone). Monitoring for cytomegalovirus (CMV) (weekly in both groups) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (weekly in RIC-group and every other week in RTC-group) reactivation by quantitative RT-PCR was conducted. Preemptive ganciclovir or valganciclovir were administered to patients with CMV reactivation (defined as ≥4000 copies/ml, reconfirmed within 24 hours from initial detection); preemptive single intravenous dose of rituximab (375mg/m2) was administered to patients with evidence of EBV replication (defined as ≥4000 copies/ml, reconfirmed within 24 hours from initial detection). Urine and/or serum BK-virus PCR was obtained in all suspected cases of hemorrhagic cystitis. The time of neutrophil engraftment was considered the first of three successive days with ANC (absolute neutrophil count) ≥ 0.5 × 109/L after post-transplantation nadir. The time of platelet engraftment was considered the first of three consecutive days with platelet count 20 × 109/L or higher, in the absence of platelet transfusion for preceding seven days.

GVHD assessment and treatment

Patients achieving neutrophil engraftment were evaluable for acute GVHD that was graded using standard criteria (20). Patients were evaluable for chronic GVHD if engraftment occurred and the patient survived for 100 days post-transplantation. The diagnoses of chronic and extensive chronic GVHD were made as previously described (21–23). Corticosteroids comprised the first-line therapy of acute (grade II-IV) and extensive chronic GVHD. Second-line treatment was at the discretion of treating physicians.

Statistical analysis

Baseline categorical variables were compared by using Fisher’s exact test, while continuous variables were compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum test or a two-sample t-test as appropriate. Overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS was defined as the time from transplant to death from any cause, and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. PFS from transplantation was calculated using death and disease progression and/or relapse as events. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was defined as death from any cause other than disease progression or relapse. Cumulative incidence was estimated for NRM and relapse risk, with relapse as a competing risk for the former and death in remission for the latter (24). Gray’s test was used to assess the difference between various subgroups for NRM and relapse rate. The probability of developing acute GVHD or chronic GVHD was depicted by calculating the cumulative incidence with relapse and death without relapse or acute GVHD or chronic GVHD as competing risks (24,25). Variables associated with acute and chronic GVHD, NRM, and relapse in the presence of a competing risk were tested individually using competing risk regression (26). Variables associated with OS and PFS analyses were run using Cox proportional hazard regression. Variables that had an association (p-value ≤ 0.10) were then entered into a multivariable analysis, either competing risk or Cox proportional hazard regression. Categorical variables were compared by using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate; while continuous variables were compared by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and OS and PFS data were analyzed by the log-rank test. All p-values are two sided. Analyses were run using Stata 11.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of 112 consecutive patients included in this analysis are shown in Table 1. Seventy-five patients received the conditioning with lower busulfan dose (6.4 mg/kg; RIC group), while thirty-seven patients received conditioning with a higher busulfan dose (~12.8 mg/kg; RTC group). The two groups did not differ significantly for age, donor source, degree of HLA (human leukocyte antigen)-match, donor/recipient CMV status, and proportion of patients with chemosensitive disease. Approximately 20% of the patients in each group received allografts from HLA-mismatched unrelated donors. More patients in the RIC group had a baseline diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, high-risk disease at the time of transplantation, and a higher median HCT-CI, while a higher proportion of RTC patients had a lower median Karnofsky performance score, underwent prior autografts, and received a higher CD34+ cell dose.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the time of transplantation.

| RIC Group N=75 |

RTC Group N=37 |

p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Age; years (range) | 58 (21–73) | 53 (34–65) | 0.13 |

| Male (%) | 69.3 | 56.8 | 0.21 |

| Diagnosis (%) | |||

| AML/ALL/MDS | 40.0% | 64.9% | |

| NHL/Hodgkin’s Disease | 24.0% | 21.6% | 0.004 |

| CLL/CML | 34.7% | 8.1% | |

| Others | 1.3% | 5.4% | |

| Disease risk‡‡ | |||

| Standard-risk | 9 (12%) | 12 (32%) | 0.01 |

| High-risk | 66 (88%) | 25 (68%) | |

| Chemosensitive disease | 51 (68%) | 28 (75%) | 0.41 |

| Prior autografting (%) | 2 (2.7%) | 5 (13.5%) | 0.03 |

| Donors | |||

| Sibling | 9 (12%) | 9 (24%) | 0.10 |

| Unrelated | 66 (88%) | 28 (76%) | |

| Degree of HLA match | |||

| 8/8 match† | 63 (84%) | 30 (81%) | 0.96 |

| 10/10 match‡ | 58 (77%) | 29 (78%) | 0.99 |

| Median KPS; (range) | 90 (70–100) | 80 (60–100) | 0.004 |

| Median HCT-CI; (range) | 2 (0–7) | 1 (0–7) | <0.001 |

| Cytomegalovirus status | |||

| Patient and/or donor seropositive | 53 (71%) | 29 (78%) | 0.38 |

| Both patient and donor seronegative | 22 (29%) | 8 (22%) | |

| Graft source | |||

| Bone marrow | 4 (5.3%) | - | 0.30 |

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 71 (94.7%) | 37 (100%) | |

| Patients receiving G-CSF* (%) | 29 (39%) | 16 (43%) | 0.64 |

| Median CD34+ cell dose (106 cells/kg recipient), (range) | 6.8 (1.7 – 12) | 7.2 (4.0 – 12.8) | <0.001 |

| Median CD3+ cell dose (107 cells/kg recipient), (range) | 2.1 (0.02 – 4.8) | 3.1 (1.1 – 9.4) | <0.001 |

p-values base on Fisher’s exact test of association for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables

Abbreviations: ALL=acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML=acute myeloid leukemia; CLL=chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML=chronic myeloid leukemia; G-CSF=granulocyte colony stimulating factor; KPS=Karnofsky performance score; HCT-CI= Hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; HLA=human leukocyte antigen; MDS=myelodysplastic syndrome; NHL=non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

8/8 match defined by high-resolution allele-level matching at HLA-A, -B, -C and –DRB1.

10/10 match defined by high-resolution allele-level matching at HLA-A, -B, -C, –DRB1 and DQB1.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase, acute leukemia in first complete remission, myelodysplastic syndrome with refractory anemia or refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts were considered to have low-risk disease. All other patients were placed in the high-risk disease category.

G-CSF use means any use before day 100. G-CSF was not routinely used to promote engraftment in either group.

Engraftment and chimerism

No primary graft failures were observed (Table 2). Median time to neutrophil engraftment (17 vs. 15 days; p=0.003) and platelet engraftment (16 vs. 11 days; p<0.001) was significantly longer in the RIC group compared to the RTC group. Two patients in the RIC group experienced secondary graft failure (ANC <0.5 × 109/L after initial neutrophil engraftment), which resolved with filgrastim (G-CSF) administration in the first patient and after donor lymphocyte infusion in the second patient. Chimerism kinetics revealed higher mean donor-cell chimerism in the RIC group at days +30 and +90 compared to the RTC group, however this difference disappeared at days +180 and +360. Rates of complete donor-cell chimerism at days +30, +90, +180 and +360 for RIC patients were 95%, 97%, 85% and 100% respectively, and for RTC patients were 94%, 91%, 83% and 90% respectively (p-values not significant).

Table 2.

Engraftment Kinetics and donor-cell chimerism post-transplantation.

| RIC Group | RTC Group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Neutrophil engraftment Mean, Median (days) (range) |

17.5, 17.0 (8 – 45) | 15.6, 15.0 (11 – 27) | 0.003 |

|

Platelet engraftment Mean, Median (days) (range) |

17.7, 16.0 (10 – 49) | 12.4, 11.0 (7.0 – 44) | < 0.001 |

|

Secondary Graft failure Secondary Graft rejection |

2 - |

- - |

0.31 NA |

|

Day +30 Chimerism Mean, Median (range) |

99.3, 100 (84 – 100) | 97.3, 100 (56 – 100) | 0.003 |

|

Day +90 Chimerism Mean, Median (range) |

97.9, 100 (17 – 100) | 96.3, 100 (40 – 100) | 0.02 |

|

Day +180 Chimerism Mean, Median (range) |

92.1, 100 (0 – 100) | 97.3, 100 (84 – 100) | 0.37 |

|

Day +360 Chimerism Mean, Median (range) |

99.9, 100 (98 – 100) | 93.6, 100 (40 – 100) | 0.30 |

GVHD

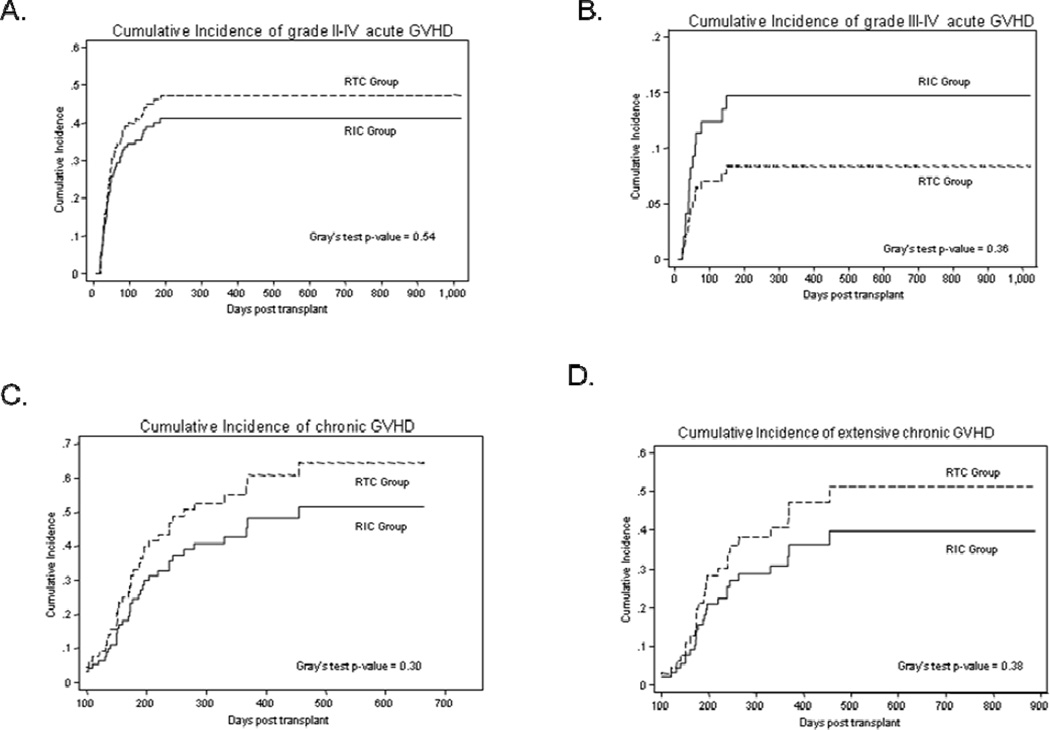

All 112 patients were evaluable for acute GVHD (Table 3). The median time to onset of acute GVHD was 42 days and 37 days for the RIC and RTC group respectively. While accounting for competing events, the day +100 cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was 34% for RIC group and 40% for RTC group (Gray’s test p=0.54) (Figure 1A). The day +100 cumulative incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD for RIC patients and RTC patients was 12% and 7% respectively (Gray’s test p=0.36) (Figure 1B). None of the relevant variables included in the univariate analysis were associated with the risk of grade II-IV and III-IV acute GVHD.

Table 3.

Assessment of graft-versus-host disease according to busulfan dose intensity.

| RIC Group | RTC Group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative incidence of acute GVHD at day +100† (%) | |||

| Grade II-IV | 34% | 40% | 0.54 |

| Grade III-IV | 12% | 7% | 0.36 |

| Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 1-year† (%) | |||

| Overall chronic GVHD | 45% | 57% | 0.30 |

| Limited chronic GVHD | 12% | 17% | 0.57 |

| Extensive chronic GVHD | 33% | 43% | 0.38 |

| Cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2-years† (%) | |||

| Overall chronic GVHD | 48% | 60% | 0.30 |

| Limited chronic GVHD | 12% | 17% | 0.57 |

| Extensive chronic GVHD | 39% | 51% | 0.38 |

Abbreviations: GVHD=graft-versus-host disease.

Represents cumulative incidence of GVHD (at specified time points), while adjusting for competing events (for details please refer to statistical methods)

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of GVHD. (A) cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD, (B) cumulative incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD, (C) cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD and (D) cumulative incidence of extensive chronic GVHD. Solid curves represent patients in RIC group, while the dashed curves represent patients in RTC group.

Ninety-six patients surviving for at least 100 days post-transplantation were evaluable for chronic GVHD (RIC group=66, RTC group=30) (Table 3). The median time to onset of chronic GVHD for RIC and RTC groups was 172 days and 162 days respectively. The 1-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at was 45% for RIC group and 57% for RTC group (Gray’s test p=0.30) (Figure 1C). The 1-year cumulative incidence of extensive chronic GVHD for the patients in RIC group vs. those in the RTC groups was 33% vs. 43% respectively (Gray’s test p=0.38) (Figure 1D). The corresponding figures for 1-year cumulative incidence of limited chronic GVHD are 12% vs. 17% respectively (Gray’s test p=0.57). The 2-year cumulative incidence rates of chronic GVHD are shown in Table 3. On univariable analysis, baseline diagnosis of chronic leukemia (HR=2.0; 95% CI=0.94–4.29; p=0.07) and HCT-CI (HR=0.75; 95% CI=0.62–0.92; p=0.005) were associated with chronic GVHD. On multivariate analysis HCT-CI remained significantly associated with chronic GVHD (p=0.004).

Infectious complications

Compared to RTC group, the patients in the RIC group had significantly fewer episodes of bacterial infections (62.2% vs. 32%; p=0.004) and (microbiologically) proven fungal infections (13.5% vs. 1.3% p=0.01) (Table 4). No significant difference in CMV reactivations (30.7% vs. 35.1%) and BK-virus associated episodes of hemorrhagic cystitis associated was seen in the RIC cohort compared to RTC patients (16% vs. 18.9%; p=0.79). One RIC patient had a disseminated adenoviral infection. EBV reactivation was significantly more common in RIC group (21% vs. 0%; p=0.001), however none of the patients in either group developed a post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder.

Table 4.

Infectious complications post allogeneic transplantation.

| RIC Group N (%) |

RTC Group N (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMV reactivation | 23 (30.7) | 13 (35.1) | 0.67 |

| EBV reactivation | 16 (21) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Adenovirus infections | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| BK-virus associated hemorrhagic cystitis | 12 (16) | 7 (18.9) | 0.79 |

| Bacterial infections | 24 (32) | 23 (62.2) | 0.004 |

| Gram positive bacteria | 17 | 18 | |

| Gram negative bacteria | 7 | 5 | |

| Invasive fungal infections | 1 (1.3) | 5 (13.5) | 0.01 |

| Aspergillus Fumigatus (Invasive pulmonary infection) |

1 | 2 | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (urinary tract infection) |

- | 1 | |

| Candida Albicans (bacteremia) |

- | 2 | |

Abbreviations: CMV=cytomegalovirus; EBV=Epstein-Barr virus.

Non-relapse mortality and relapse rate

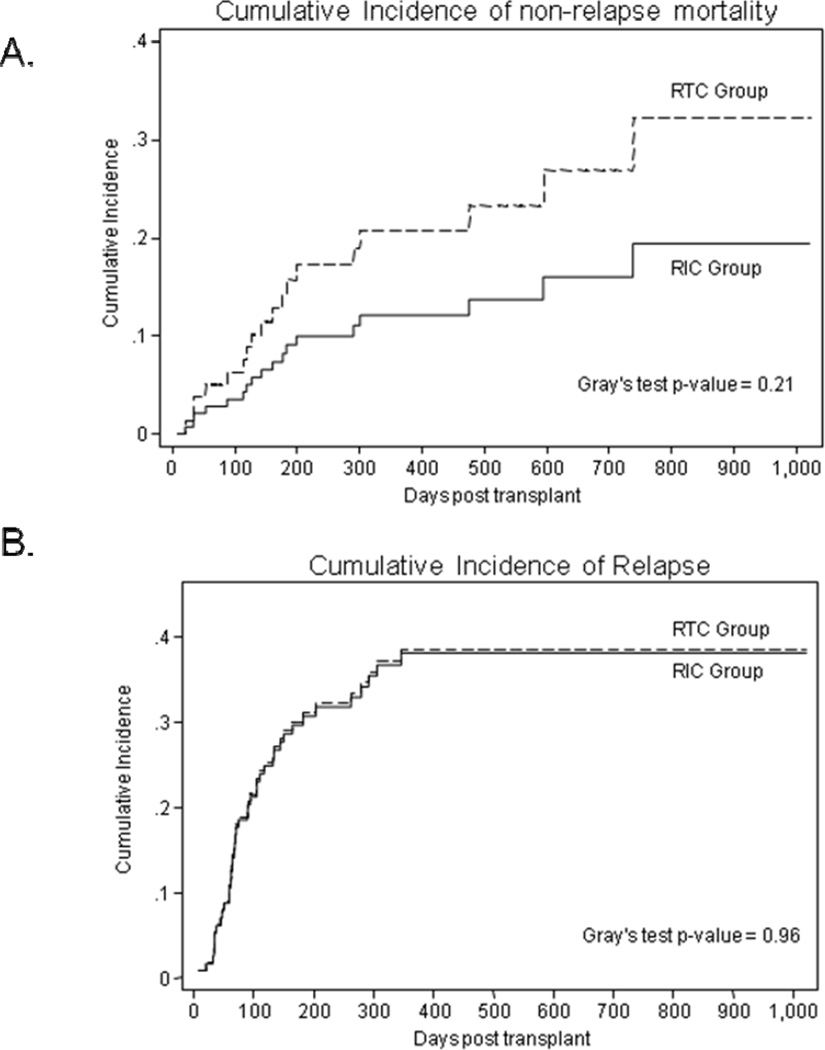

Median follow-up of surviving patients following HSCT is 15 months. The day 100 cumulative incidence of NRM rate in the RIC and RTC group was 3% vs. 6% (Gray’s test p=0.03) respectively. At 1-year (12% vs. 21%) and 2-years (19% vs. 32%) post HCT the cumulative incidence of NRM showed a (statistically non-significant) trend favoring RIC group (Figure 2A). On multivariate analysis advanced age (HR=1.08; 95% CI=0.03–1.13; p=0.001) and HLA-mismatched HCT (HR=4.56; 95% CI=1.61–12.9; p=0.004) were significantly associated with NRM risk. Causes of NRM in RIC group included; GVHD with (n=2) and without gram negative sepsis (n=2), cardiac failure (n=1), sepsis (n=3), CMV encephalitis (n=1) and respiratory failure (n=1). In contrast in the RTC group causes of NRM included; GVHD with sepsis (n=2), respiratory failure (n=2), sepsis (n=3), and fungal infection (n=1).

Figure 2.

(A) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality according to the intensity of conditioning regimen. (B) Cumulative incidence of disease relapse according to the intensity of conditioning regimen. Solid curves represent patients in RIC group, while the dashed curves represent patients in RTC group.

At last follow-up 40 patients have experienced disease relapse (RIC=27; RTC=13). The cumulative incidence of relapse for RIC and RTC patients was not significantly different (Gray’s test p=0.96); the 100 day, 1- and 2-year rates for the two groups were 22% vs. 22%, 38% vs. 39% and 38% vs. 39% respectively (Figure 2B). On univariate analysis chemosensitive disease at transplant, Karnofsky performance score, HLA-mismatched allograft were associated with the relapse risk. On multivariate analysis only chemosensitive disease at transplantation was associated with reduced risk of disease relapse (HR=0.53; 95% CI=0.28–0.97; p=0.039).

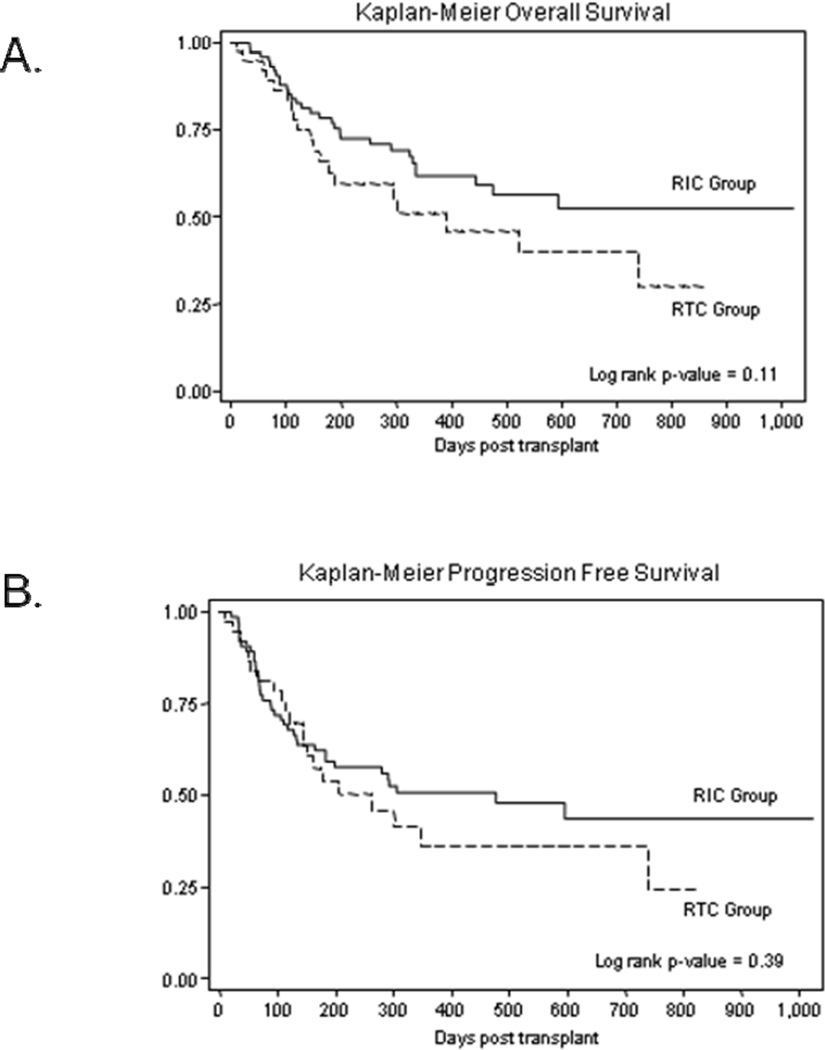

Overall and Progression free survival

At last follow-up 64 patients were alive (RIC group=46, RTC group=18). 1-year OS for patients in RIC and RTC groups was not significantly different (61% vs. 50%; log-rank p=0.11) (Figure 3A). The 2-years expected OS rates were 52% and 40% respectively. Univariate analysis identified male sex (HR=0.53; p-value=0.03), baseline diagnosis of chronic leukemia (HR=0.54; p-value=0.09), and G-CSF use (HR=1.77; p-value=0.05) as variables of interest for multivariable analysis. On multivariate Cox regression analysis male sex (HR=0.57; 95% CI=0.30–0.94; p=0.029) and G-CSF use post HCT (HR=1.79; 95% CI=1.01–3.17; p=0.046) maintained their prognostic significance for OS. The 1-year PFS rates were 50% and 36% for patients in RIC group and those in RTC group respectively (log-rank p-value=0.39) (Figure 3B). The corresponding estimates of 2 year PFS rates were 43% and 36% respectively. Univariate analysis did not identify any variables to be significantly associated with PFS.

Figure 3.

Overall survival and progression free survival according to the intensity of conditioning regimen. (A) Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival following allogeneic transplantation, (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression free survival following allogeneic transplantation. Solid curves represent patients in RIC group, while the dashed curves represent patients in RTC group.

Discussion

In this study we have analyzed the relative importance of intravenous busulfan’s dose intensity on the outcomes of patients undergoing RTC/RIC allogeneic HCT and make several interesting observations. First our data suggest that a higher busulfan dose may be associated with more frequent infectious complications. Second, the busulfan dose intensity was not associated with the risk of developing either acute or chronic GVHD. Third, the busulfan dose intensity did not impact the risk of disease relapse, but a higher dose showed a trend towards increased NRM, (likely) secondary to more frequent infectious complications.

While conventional myeloablative preparative regimens (cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation [TBI] or cyclophosphamide/busulfan [Bu/Cy] etc.) are associated with unacceptably high rates of NRM in patients with advanced age or medical comorbidities (17), the benefits of lower intensity regimens might be offset by increased relapse rates. Alyea et al. retrospectively compared outcomes of older patients undergoing allogeneic HCT with myeloablative (mostly cyclophosphamide/TBI) or NMA conditioning (fludarabine 120 mg/m2, busulfan 3.2 mg/kg; total dose) (16). While NMA conditioning was associated with improved NRM, relapse rates in the NMA group were significantly higher. These results, while not unexpected considering the significant difference in the intensity of conditioning regimens between the two groups, underscore the contribution of conditioning regimen’s intensity in providing disease control under a graft-versus-tumor effect establishes. Shimoni et al. (27) retrospectively compared outcome of patients receiving myeloablative conditioning with Bu/Cy with ones undergoing either RIC (n=41) or RTC (n=26) with fludarabine and busulfan, and reported higher NRM but lower relapse rates with Bu/Cy. Others have reported similar data when comparing conventional myeloablative regimens with RIC allografts (28).

Whether the intensity of conditioning is equally important within the spectrum of NMA, RIC or (the so-called) RTC regimens remains controversial. Cahu et al. (29) in a small retrospective study (n=31) compared outcomes of leukemia patients undergoing RIC allogeneic HCT either following a less intense (fludarabine 120 mg/m2; busulfan 4 mg/kg, ATG 5 mg/kg) or more intense (fludarabine 150–180 mg/m2; oral busulfan 8 mg/kg; ATG 2.5 mg/kg) conditioning regimen. In this study the leukemia free survival, OS, and relapse rates significantly favored a more intense conditioning regimen. However it important to note that (a) all patients receiving more intense conditioning also received planned high dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation before RIC allografting, and (b) patients in the less intense group received a higher ATG dose. Whether the differences in the outcomes of these two conditioning regimens are largely attributable to the difference in the degree of pre-transplant therapy or post-transplant immunosuppression is unknown. In contrast, in our study no difference in the rates of disease relapse is seen when comparing outcomes of patients undergoing RTC with a myeloablative busulfan dose (RTC group) or ones getting RIC with a nearly ablative busulfan dose (RIC group). It is however important to point out that the patient population included in our study is heterogeneous with significantly more patients with chronic leukemias (predominantly heavily pretreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia) in the RIC cohort and a higher proportion of acute leukemias in RTC group. While acknowledging this heterogeneity it is also interesting to note that the relapse rates between the two groups are not significantly different despite a higher proportion of patients in the RIC group with a high relapse-risk disease by standard CIBMTR criteria (14). The relapse rates observed in the RTC group in our study are comparable to previous studies using a similar conditioning regimen (10,11,30). Similarly while the NRM with RTC in our experience appears to be higher than the incidence rates in studies which included a relatively homogeneous patient population with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia (10), they appear similar to NRM rates seen in other studies which report on a more heterogeneous patient population (30).

Significantly faster neutrophil and platelet engraftment was noted in the RTC group, compared to RIC patients. This difference is likely due to a higher CD34+ cell dose infused and a non-methotrexate containing GVHD prophylaxis employed in the RTC cohort. Rates of EBV reactivation were significantly lower in RTC group. No difference was seen between the two groups in terms of ATG dose used and donor/recipient EBV seropositivity to explain this outcome. While EBV surveillance in RTC group was performed every two weeks compared to weekly monitoring in RIC group, this difference does not provide a plausible explanation of this difference. Similarly while a higher infused CD3+ dose in RTC patients can theoretically be responsible for this difference, more frequent infectious complications in this cohort argue against this. It is important to note that despite a more robust engraftment, bacterial and fungal infections were significantly more common with RTC in our study. While application of ATG in transplant conditioning has previously been shown to be associated with higher infectious complications (13,14,31), we employed an identical dose in both groups. Both cohort of patients also received similar infectious disease prophylaxis. It is plausible that a more intense conditioning might be associated with delayed immune reconstitution and resultant frequent infectious complications; however unknown biological differences between the patients undergoing transplants uniquely at two different transplant centers in our study cannot be excluded. Regardless of the cause, the more frequent infectious complications in RTC groups are likely largely responsible for trends towards higher NRM seen in this cohort.

In summary, our data suggest that in the context of RIC/RTC transplantation, escalation of busulfan doses from nearly myeloablative doses (6.4 mg/kg intravenous) to clearly myeloablative doses (~12.8 mg/kg intravenous) is associated with similar survival, relapse rates and trends towards slightly higher NRM resulting from frequent infectious complications with RTC conditioning. Our results need cautious interpretation considering the fact that they are limited by their retrospective nature and heterogeneity of patients included in the study, but they highlight the need for prospective comparative evaluation of various RIC regimens in specific diseases to define the regimens with best risk-benefit ratio.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported in part by research funding by American Cancer Society 116837-IRG-09-061-01 (M.H) and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. (M.H & S.M.D).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure and Propriety Statement: Nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamadani M, Awan FT, Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(5):556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringden O, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Biggs JC, Gajewski J, Rimm AA, et al. Outcome after allogeneic bone marrow transplant for leukemia in older adults. JAMA. 1993;270(1):57–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510010063030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingemann HG, Storb R, Fefer A, Deeg HJ, Appelbaum FR, Buckner CD, et al. Bone marrow transplantation in patients aged 45 years and older. Blood. 1986;67(3):770–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rezvani AR, Storer B, Maris M, Sorror ML, Agura E, Maziarz RT, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in relapsed, refractory, and transformed indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):211–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rezvani AR, Norasetthada L, Gooley T, Sorror M, Bouvier ME, Sahebi F, et al. Non-myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre experience. Br J Haematol. 2008;143(3):395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyurkocza B, Storb R, Storer BE, Chauncey TR, Lange T, Shizuru JA, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2859–2867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohrt HE, Turnbull BB, Heydari K, Shizuru JA, Laport GG, Miklos DB, et al. TLI and ATG conditioning with low risk of graft-versus-host disease retains antitumor reactions after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Blood. 2009;114(5):1099–1109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lima M, Couriel D, Thall PF, Wang X, Madden T, Jones R, et al. Once-daily intravenous busulfan and fludarabine: clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a myeloablative, reduced-toxicity conditioning regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in AML and MDS. Blood. 2004;104(3):857–864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell JA, Turner AR, Larratt L, Chaudhry A, Morris D, Brown C, et al. Adult recipients of matched related donor blood cell transplants given myeloablative regimens including pretransplant antithymocyte globulin have lower mortality related to graft-versus-host disease: a matched pair analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(3):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91(3):756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohty M, Jacot W, Faucher C, Bay JO, Zandotti C, Collet L, et al. Infectious complications following allogeneic HLA-identical sibling transplantation with antithymocyte globulin-based reduced intensity preparative regimen. Leukemia. 2003;17(11):2168–2177. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamadani M, Blum W, Phillips G, Elder P, Andritsos L, Hofmeister C, et al. Improved nonrelapse mortality and infection rate with lower dose of antithymocyte globulin in patients undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(11):1422–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corradini P, Dodero A, Zallio F, Caracciolo D, Casini M, Bregni M, et al. Graft-versus-lymphoma effect in relapsed peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas after reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic transplantation of hematopoietic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2172–2176. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alyea EP, Kim HT, Ho V, Cutler C, Gribben J, DeAngelo DJ, et al. Comparative outcome of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age. Blood. 2005;105(4):1810–1814. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flomenberg N, Baxter-Lowe LA, Confer D, Fernandez-Vina M, Filipovich A, Horowitz M, et al. Impact of HLA class I and class II high-resolution matching on outcomes of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation: HLA-C mismatching is associated with a strong adverse effect on transplantation outcome. Blood. 2004;104(7):1923–1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przepiorka D, Ippoliti C, Khouri I, Woo M, Mehra R, Le Bherz D, et al. Tacrolimus and minidose methotrexate for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease after matched unrelated donor marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;88(11):4383–4389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer ER. The histopathology of graft-versus-host disease. Adv Dermatol. 1986:1173–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69(2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan KM, Agura E, Anasetti C, Appelbaum F, Badger C, Bearman S, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and other late complications of bone marrow transplantation. Semin Hematol. 1991;28(3):250–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohty M, Bay JO, Faucher C, Choufi B, Bilger K, Tournilhac O, et al. Graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic transplantation from HLA-identical sibling with antithymocyte globulin-based reduced-intensity preparative regimen. Blood. 2003;102(2):470–476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimoni A, Hardan I, Shem-Tov N, Yeshurun M, Yerushalmi R, Avigdor A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in AML and MDS using myeloablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning: the role of dose intensity. Leukemia. 2006;20(2):322–328. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hari P, Carreras J, Zhang MJ, Gale RP, Bolwell BJ, Bredeson CN, et al. Allogeneic transplants in follicular lymphoma: higher risk of disease progression after reduced-intensity compared to myeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(2):236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahu X, Mohty M, Faucher C, Chevalier P, Vey N, El-Cheikh J, et al. Outcome after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT for AML in first complete remission: comparison of two regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(10):689–691. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geddes M, Kangarloo SB, Naveed F, Quinlan D, Chaudhry MA, Stewart D, et al. High busulfan exposure is associated with worse outcomes in a daily iv, busulfan and fludarabine allogeneic transplant regimen. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(2):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Blood. 2001;98(10):2942–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]