Abstract

Male circumcision (MC) can prevent female to male HIV transmission and has the potential to significantly alter HIV epidemics. The ultimate impact of MC on HIV prevention will be determined, in part, by behavioral factors. In order to fully realize the protective benefits of MC, factors related to acceptability and sexual risk must be considered. Research shows that acceptability of MC among uncircumcised men is high and suggests that free and safe circumcision may be taken up in high-HIV prevalence places. Perceptions of adverse effects of MC may however limit uptake. Furthermore, considerable risk reduction counseling provided by MC trials limits our ability to understand the impact MC may have on behavior. There is also no evidence that MC protects women with HIV positive partners or that it offers protection during anal intercourse. Research is urgently needed to better understand and manage the behavioral implications of MC for HIV prevention.

Introduction

As we approach 30 years of AIDS there are few effective strategies in use to prevent the spread of HIV. The most successful HIV prevention discovery is antiretroviral therapy administered to avert mother-to-child transmission. Most disappointing have been the challenges to developing an effective preventive vaccine and the lack of resources dedicated to scale-up evidence-based effective behavioral interventions (1). Fortunately, there is now compelling evidence that male circumcision (MC) reduces the risk for heterosexual HIV transmission. Years of epidemiological evidence shows that HIV infection risks are between two and eleven times higher in uncircumcised men than circumcised men (2–3). The biological plausibility that MC protects against HIV infection has been well-established, principally by removing the foreskin there are dramatic reductions in HIV infectable cells (T-cells, and macrophages) as well as excising cells that transport virus across epithelia, particularly Langerhans cells (3–4). Most compelling are the results of three randomized clinical trials (RCT) of MC for HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Each of three RCTs conclusively demonstrated as much as a 60% protective effect of MC against HIV transmission (5–7).

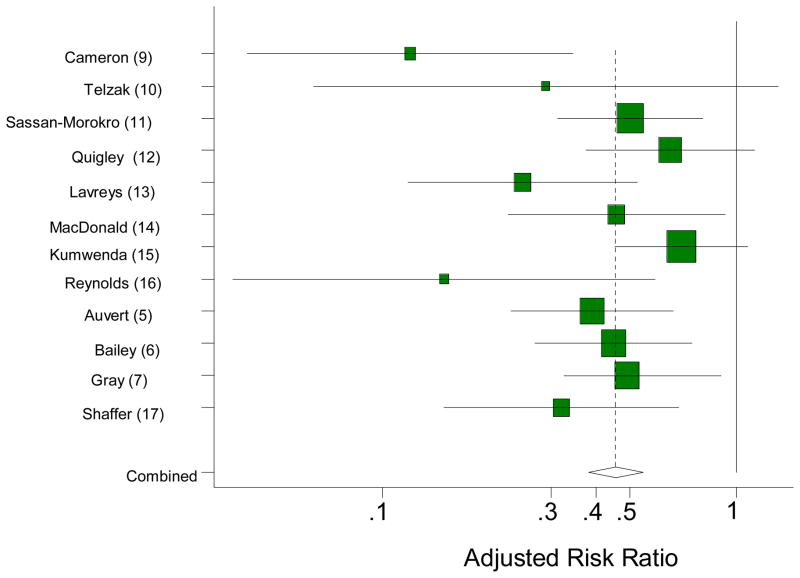

A recent meta-analysis reported by Byakika-Tusiime (8) summarizes the evidence that MC offers significant partial protection against female-to-male HIV transmission. The findings include both epidemiologic evidence (9–17) and the three RCTs (5–7). As shown in Figure 1, the evidence for partial protection of MC against HIV infection is consistent across the various types of studies. Byakika-Tusiime concluded that while there is some tentative suggestion of publication bias toward under-representing smaller studies that show risk elevating effects of MC, the evidence for protective benefits resulting from MC is overwhelming. In addition, Byakika-Tusiime shows that MC meets six of Hill’s (18) nine criteria for demonstrating causal effects of interventions including the strength and consistency of the association between MC and HIV infection, the temporal association between MC and disease, biological plausibility, coherence of research findings, and the experimental evidence of RCTs. With evidence this compelling it appears that there is no public health minded rationale to delay the immediate scale-up of MC for HIV prevention in places with generalized HIV epidemics.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of adjusted Risk Ratios reprinted with permission from Byakika-Tusiime (8), AIDS and Behavior, vol. 12, page 838 (reprinted with permission, Springer Science and Business Media). The squares represent the individual studies and the horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. The size of each square is proportional to the study’s weight in the meta-analysis. The dotted vertical line represents the overall meta-analyzed measure of effect. The diamond represents the pooled/combined effect after meta-analysis and the 95% confidence interval. The solid vertical line represents no effect.

MC is currently being implemented in widespread scale up programs in some southern African countries such as Botswana (19), while most other countries in the region are considering plans for rolling out MC programs as recommended by the WHO, UNAIDS, and other policy guiding institutions (20). MC could significantly impact the course of AIDS epidemics in Africa over the next 20 to 30 years (21). The degree to which MC will achieve its prevention potential will ultimately be determined by whether low-cost and safe MC is accessible and by the behavior of men targeted by MC for HIV prevention programs.

In this paper we review the behavioral aspects of MC as an HIV prevention strategy. First we examine the evidence for acceptability of MC among men and women as well as the potential effects of MC on sexual functioning as it relates to acceptability. We then consider the implications of behavioral changes that may occur in response to MC, particularly behavioral adjustments aimed toward risk compensation among men undergoing the procedure. Finally, we discuss the behavioral practices and gender-related limitations of MC on reducing risks for HIV transmission among women and men who have sex with men (MSM). We conclude with suggestions for a behavioral science research agenda to answer remaining questions regarding MC for HIV prevention.

Acceptability of Male Circumcision

Acceptability research on MC for HIV prevention suggests that as many as 50% to 70% of uncircumcised men may be willing to undergo circumcision (22). Factors that most reliably influence willingness to accept MC include improved hygiene, safety of the procedure, limited surgical and post-operation pain, and protection against STI and HIV. Similar factors influencing MC acceptance are reported outside of African heterosexual men, such as MSM in China (23). Research with African-American MSM also finds that as many as 80% state that they would be willing to be circumcised if it would protect them against HIV (24). More than half of women in MC acceptability studies report that they prefer circumcised men for sex partners (22,25). While acceptability research allows us to have a sense for the marketability of an intervention such as MC, expressed interest in a prevention technology does not always translate to uptake. In other words, acceptability studies rely on responses to hypothetical products and interventions which may not reflect the reality of actual use. Thus, acceptability studies cannot, by their very design match the reality of decisions to use a product or undergo a medical procedure (26).

Few studies are yet available on actual uptake of MC prevention services. Data from the three RCTs suggest that once men agree to circumcision they may follow through. In the South African RCT (5) only 5% of men screened refused to participate in the trial and 6% of men randomized to receive MC dropped out before having surgery. However, 8% of men in the control condition crossed-over and underwent circumcision. In the Kenya trial (6) the refusal rate for participation was 23% but only 4% of men scheduled for MC dropped out and less than 1% of controls crossed-over. Similar rates of refusal and opting out of circumcision were reported in the Uganda trial (7). Although the incentives for participating in an RCT are not mimicked in clinical practice, the overall participation rates and follow-through in the RCTs does suggest a high-degree of acceptance of MC.

One study outside of the MC RCTs provides a sense for what may be a more realistic estimate of uptake. Research conducted with men in a South African vaccine cohort reported that male participants were offered free and safe MC as an ethical option for prevention within the vaccine trial (27). The study found that 17% of uncircumcised men took advantage of the opportunity to receive MC using state of the art surgical procedures. Importantly, men who accepted MC had more HIV positive sex partners and were more likely to have had a recent STI. The greater likelihood of seeking MC among higher risk men will be critical to MC achieving optimal protective effects. The greater the uptake of MC among higher risk men the larger the public health impact. Still, less than one in five men requested circumcision and these men were already motivated to participate in a vaccine trial. Circumcision uptake will have to be significantly greater than one in five men to achieve population reductions in HIV infection (21).

Sexual Functioning

A potential barrier to men seeking and following through with MC may result from the perception that circumcision adversely impacts sexuality and sexual functioning. Removal of the foreskin is associated with concerns about reduced sensitivity and penile sensation (28), and in some studies of men who undergo circumcision reduced sensation is reported (28–29). One study in South Korea (30), for example, found that two thirds of men who underwent MC reported increased difficulty masturbating after the procedure and while only 6% stated that their sex lives improved post-circumcision, 20% felt that their sex lives were worsened by circumcision. However, adverse outcomes were not universal. The Kenya MC RCT examined several dimensions of sexual functioning and sexual performance after circumcision including self-reported penile sensitivity, orgasmic functioning, and a wide range of sexual dysfunctions (31). Overall, results from the Kenya MC RCT found little evidence for adverse effects of MC. To the contrary, men reported progressively increased penile sensitivity and sexual pleasure over the observation period.

Differences in sexual functioning following MC across studies may reflect the variance in surgical procedures, instruments, and infection control, especially differences between culturally traditional and medical MC. State of the art practices and infection control standards designed to limit nerve damage and reduce scarring are used in studies of medical circumcision (5–7, 27). In contrast, MC practices used in traditional and religious rituals as well as medical practices in some resource poor settings do not follow such rigorous standards. A study of traditional circumcision practices in South Africa, for example, found that while 85% of practitioners wore gloves during circumcision, 53% of circumcised men reported that their foreskin was removed with a traditional instrument, such as a spear (32).

Behavioral Risk Compensation

Risk compensation occurs when the perceived chance that a threatening event will occur is altered and behavior is adjusted in response to the perceived change in probability of the threat (33). In the case of MC, risk compensation can result when perceived risks for HIV infection are lowered due to new information and beliefs about the protective benefits of circumcision. The extent to which risk compensation will attenuate the protective benefits of a widespread scale-up of MC, such as that occurring in Botswana, is difficult to estimate with currently available data. Findings from the three completed MC RCTs are mixed in terms of the effects of MC on post-circumcision sexual behavior and the services offered in an RCT will not be replicated in most MC programs. Of particular concern is the extent to which a substantial rollout of MC will mirror the repeated sessions of risk reduction counseling that were provided in the three RCTs. The combination of a history of limited resources committed to behavioral interventions and the obvious attraction of a one-time surgical fix for the problem of HIV transmission may result in a scale-up of MC void of any risk reduction counseling. Assuming that extensive risk reduction counseling as provided in the RCTs will not be included in an MC rollout, it is unclear how pervasive risk compensation in response to MC will be in real world settings.

Evidence for risk compensation

The South African MC RCT (5) is the only of the three trials to show consistent patterns of risk compensation following circumcision. In this trial circumcised men reported more sexual partners than uncircumcised men at the 4 month – 12 month recall period (5.9 versus 5.0, p <.001) and at the 13 month – 21 month recall period (7.5 versus 6.4, p <.01). Other sexual risk variables showed more risk taking among circumcised men but were not significant.

Data from the Kenya trial (6) showed fairly consistent evidence for reductions in risk and increases in protective behaviors among both circumcised and uncircumcised men. However, differences in risk between groups did emerge. In terms of the number of men who reported two or more sex partners in the past six months at follow ups, uncircumcised men reported a greater decrease in the number of partners than did circumcised men when examining linear trends over the course of the study, 42% of both groups reported this behavior at baseline and 35% [6 month], 33% [12 month], 30% [18 month], 27% [24 month] subsequently at follow ups for uncircumcised men and 33%, 29%, 30%, 30%, respectively for circumcised men (p <.05). Moreover, unprotected intercourse with any partner decreased less between baseline and 24 month follow up for circumcised men (63%-51%) versus uncircumcised men (63%-46%, p <.05) and consistent condom use increased less for circumcised men (22%–36%) versus uncircumcised men (21%–41%, p <.05). Men in the Kenya trial also reported consistent increases in frequency of engaging in sex with 12% reporting increased frequency at 6-months, 17% at 12-months, 26% at 18-months, and 29% reporting increased frequency of sex since being circumcised at the 24 month follow-up (29). Likewise, these data parallel increases in the belief that men felt protected against STI and HIV; 54% stated that they felt protected 6-months after surgery and 68% felt protected by 24-months after surgery.

Further investigation into risk compensation in the Kenya trial (34) demonstrated no marked increase in sexual risk behavior among circumcised men. Again, both circumcised and uncircumcised men reduced their sexual risk behaviors on multiple dimensions measuring sexual risk over the course of the study. However, circumcised men were diagnosed with sexually transmitted infections (STI) at a higher rate of infection than uncircumcised men, but this difference was attributed to higher baseline STI rates among circumcised men when compared with uncircumcised men. Moreover, analyses of the Kenya trial shows that both circumcised and uncircumcised men reduced their sexual risk behavior over the course of the trial, although not equally (35).

In Uganda (7) sexual risk behavior was similar for both uncircumcised men and circumcised men at study follow ups. Inconsistent condom use was higher among circumcised men (37% versus 31% p <.001), however no condom use was higher among uncircumcised men (52% versus 45% p <.001) for the 6 month follow up only. As for longitudinal trends, evidence is mixed in terms of risk behavior change among both groups when comparing baseline to the 24 month follow up. For example, no condom use appears to decrease, and both consistent and inconsistent condom use appear to increase somewhat over the course of the study for both groups. We should note that percentages were recalculated for baseline data to exclude what appear to be individuals not reporting sexual behavior, and differences may not be significant.

Testing for risk compensation in randomized controlled trials

The necessary ethical considerations of MC RCTs work against our ability to understand risk compensation in this context. For example, in the Uganda trial participants received HIV risk reduction counseling at baseline, 4–6 week, 6, 12, and 24 month follow ups (7); in the Kenya study participants received HIV prevention counseling at baseline, 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 month follow ups; and in South Africa participants received HIV prevention counseling at baseline, 3, 12, and 21 month follow ups (5). RCTs demand considerable attention to engaging and retaining participants. These trials also allow for significant amounts of time to address risk behaviors and risk decision making during counseling. The service resources offered to participants in an RCT therefore contrast with the limited clinical attention and follow-up offered in real world settings. Unless the rollout of MC includes persistent risk reduction counseling similar to what was used in the RCTs, the behavioral implications of MC remain to be seen. Furthermore, it is the findings from the RCTs themselves that are expected to impact social norms and protective beliefs. Because the results were not part of the experience of men in the trials these effects could not occur. Unlike other biomedical technologies that can be used intermittently, such as microbicides, MC is a permanent procedure and thus may have long term behavioral implications that evolve as social norms and beliefs about MC change.

Complexities of communicating partial protection

Although data suggests that people tend to understand the difference between partial protection and full protection (36), articulating a prevention message that encourages both MC and safer sexual behaviors such as condom use is not straight forward. Because MC reduces HIV risk by about a half to two-thirds, the challenge is to communicate in understandable terms that MC decreases the likelihood of infection but does not prevent infection entirely. In other words, on a societal level MC is very promising for resulting in reduced infections, but individually MC alone is not reliable for HIV prevention. Crafting a compelling prevention message relevant to the individual as well as the collective community is necessary and may help dampen risk compensation. Men who understand that MC is partially protective will be more likely to use condoms and reduce partners following circumcision. Men who understand they will still need to use condoms and reduce partners may opt out of MC altogether if their motivation to undergo circumcision is solely to protect themselves against HIV and STI without using condoms. Thus, other methods of prevention need to be employed in conjunction with MC, such as counseling for consistent condom use. The full protocol of the MC RCTs that includes risk reduction counseling and follow up, not just the state of art surgery, provides a model for MC implementation that should be mirrored in practice.

Moving towards fully understanding the implications of risk compensation

Because risk compensation is, in part, a behavioral adaptation to new and evolving information tests for risk compensation must approximate real life settings as much as possible. Thus, sound ecological validity is critical in any test of risk compensation. At this point, it is unclear what the sexual risk profiles will look like of men who seek MC for HIV prevention outside of an RCT. If high-risk men seek out MC then the concerns for risk compensation may be moot because of their already elevated risk, and in theory these men would only benefit from MC.. However, should lower risk men seek out MC then concerns for the effects of risk compensation should be taken seriously. These men may increase their risk practices to compensate for their lower perceived risk following MC. In order to maximize the protectiveness of MC, men seeking circumcision as part of a widespread rollout would ideally be monitored long term for increases in sexual risk behaviors.

On the whole, in the RCTs, it appears that both circumcised and uncircumcised men reduced their risk behaviors throughout the course of the trials, with some evidence for circumcised men reducing their risk behavior less so than uncircumcised men. Generally speaking, risk compensation occurs when risk behavior increases as a result of a change in the environment; however in the case of MC this scenario did not occur. Instead what we observe is a possible difference in the rate at which risk behavior decreased, with evidence for a sharper decrease among uncircumcised men in response to persistent risk reduction counseling. Nevertheless, there exist concerns for risk compensation to hinder the protective benefits of MC when performed under real world circumstances.

Sexual Behaviors and Protective Effects

Most of the available evidence regarding the efficacy of MC focuses on vaginal intercourse practiced by men in southern Africa, although there is evidence that the protective benefits of MC for HIV prevention extend to other regions (37). Unfortunately, few studies of MC report rates of anal intercourse disaggregated from vaginal intercourse. The biological bases for expanding protective benefits of MC may not generalize to anal intercourse because of differences in sexual dynamics, tissue trauma, exposure to blood, and immunological surface differences between the anal cavity and the vaginal walls. Thus, while heterosexual anal intercourse is infrequent (38–39), the relatively greater risk for HIV transmission during anal intercourse may diminish the protection offered by MC.

Female partners of circumcised men are not consistently protected by MC during vaginal intercourse. Specifically, a sero-discordant partner’s study in conjunction with the Uganda MC RCT (40) found no protective effects from MC for women with HIV positive male partners. In fact men who engaged in sex before complete healing of their circumcision wound demonstrated considerable increased risk for HIV transmission. These data led the WHO and UNAIDS to not recommend promoting MC for HIV positive men (20). There is also little evidence that MC offers protective benefits to MSM. While the risks of anal intercourse to receptive partners lacks biological plausibility for a protective benefit of MC, there also seems to be minimal protective effects of MC for the insertive anal sex partner as well. One study showed that MC offered no protective effect to MSM regardless of their sexual positioning (41). In contrast, a history of other STI was consistently associated with HIV infection. In addition, a meta-analysis of studies representing over 53,000 MSM, 52% of whom were circumcised, found limited evidence of protective benefits against STI and HIV (42).

The protective benefits of MC are also attenuated by age of circumcision. Of course, circumcision prior to sexual debut will render the greatest lifetime protection. In the South African MC RCT over 90% of men were already sexually active prior to undergoing circumcision. On average men had their first sexual experience before age 17 whereas only half of the men in the trial were under 21 years old (5). Similarly, 90% of traditionally circumcised men in one South African study were sexually active prior to the procedure (32). A nationally representative study of men in South Africa found that 40% were circumcised after becoming sexually active and rates of circumcision did not differ between men who were HIV positive and men who were HIV negative (43). Finally, the protective effects of MC against other STI is at best inconclusive. Cross-sectional studies report discrepant results regarding MC for protection against STI and longer term prospective studies are more pessimistic. For example, a birth cohort of men in New Zealand found no evidence that MC offers protective benefits against bacterial or viral STI (44).

Conclusions

MC significantly reduces the risk of female-to-male vaginal intercourse transmission of HIV and has the potential to alter the course of AIDS epidemics in southern Africa. Ultimately acceptance and uptake of MC as well as managing post-circumcision behavioral risk compensation will determine the population impact of MC. At this point, information on the behavioral ramifications of MC is too limited to forecast outcome trajectories. Here we join others in calling attention to the need for carefully conducted behavioral research around circumcision for HIV prevention.

Brooks et al. (45) and Sawires et al. (46) offered suggestions for advancing behavioral science research concerning circumcision for HIV prevention. Behavioral research is needed to determine the factors that predict acceptance, engagement, and retention of high-risk men for MC services in real world settings. Factors that influence the uptake of MC should be identified and used to tailor MC marketing strategies and services. We need to better understand how social networks and community norms are altered as MC is introduced and scaled up. Ramping up of demand for MC will occur to the degree to which men perceive the procedure as safe and relatively painless as well as experience protection against STI and HIV. By the same token, communities will resist MC to the degree that men experience adverse outcomes. Social and behavioral processes fluctuate over time and will require careful and thoughtful programmatic research.

Sound behavioral science research is also needed to examine risk compensation in response to MC outside of RCTs and other artificial contexts. For example, research is needed to understand the changes in beliefs and perceptions in men who elect to undergo MC and the long term behavior changes that ensue. In addition, as community norms shift toward beliefs of MC offering protection against HIV, women’s preferences for circumcised partners will likely increase. Research is needed to observe whether women begin selecting circumcised partners, a practice termed circum-sorting, and whether this practice is based on an understanding of partial protection, whether it is associated with reductions in condom use, and whether it leads to stigmatization of uncircumcised men. Understanding and monitoring changes in social relations that may result from widespread MC programs should be a behavioral science priority.

Finally, research is needed on the cultural and social forces that influence the politics and policies that surround adopting MC as an HIV prevention strategy. It is indeed unwise to ignore the cultural meaning of circumcision and its relationship to perceptions of masculinity, social roles, tribal identities, parenting practices, rites of passage, and religious covenants when constructing MC programs. Any meaningful behavioral research agenda concerning MC for HIV prevention will require careful attention to the socio-cultural context of circumcision.

Acknowledgments

National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH071160 and T32 MH074387, and National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01 AA017399 and R01 AA018074 supported preparation of this review.

References

- 1.Kalichman SC. Time to take stock in HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:333–334. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moses S, Plummer FA, Bradley JE, Ndinya-Achola JO, Nagelkerke NJ, Ronald AR. The association between lack of male circumcision and risk for HIV infection: a review of the epidemiological data. Sex Transm Dis. 1994 Jul-Aug;21(4):201–10. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinn TC. Circumcision and HIV transmission. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007 Feb;20(1):33–8. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328012c5bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris BJ. Why circumcision is a biomedical imperative for the 21(st) century. Bioessays. 2007 Nov;29(11):1147–58. doi: 10.1002/bies.20654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: The ANRS 1265 trial. PLoS Medicine. 2005;11:1112–1122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, Williams CFM, Campbell RT, Ndinya-Achola JO. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. Among the randomized trials for male circumcision to prevention HIV infection, this trial provides the most complete behavioral data and examination of risk compensation. The data are used in subsequent secondary analyses further elaborating on the behavioral changes that occurred in the cohort. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Byakika-Tusiime J. Circumcision and HIV Infection: Assessment of Causality. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:835–841. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9453-6. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for the protective effect of male circumcision against HIV infection. The paper examines epidemiologic evidence and clinical trial outcomes. The author uses objective criteria for determining potential publication bias and causality of circumcision preventing HIV infection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D’Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, Gakinya MN, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: Risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2(8660):403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telzak EE, Chiasson MA, Bevier PJ, Stoneburner RL, Castro KG, Jaffe HW. HIV-1 seroconversion in patients with and without genital ulcer disease. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1181–1186. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-12-199312150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sassan-Morokro M, Greenberg AE, Coulibaly IM, Coulibaly D, Sidibe K, Ackah A, et al. High rates of sexual contact with female sex workers, sexually transmitted diseases, and condom neglect among HIV-infected and uninfected men with tuberculosis in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. J Acquire Immune Defic Synd Human Retrovirology. 1996;11:183–187. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199602010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quigley M, Munguti K, Grosskurth H, Todd J, Mosha F, Senkoro K, et al. Sexual behaviour patterns and other risk factors for HIV infection in rural Tanzania: A case-control study. AIDS. 1997;11(2):237–248. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavreys L, Rakwar JP, Thompson ML, Jackson DJ, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, et al. Effect of circumcision on incidence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and other sexually transmitted diseases: A prospective cohort study of trucking company employees in Kenya. J Infec Dis. 1999;180(2):330–336. doi: 10.1086/314884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald KS, Malonza I, Chen DK, Nagelkerke NJ, Nasio JM, Ndinya-Achola J, et al. Vitamin A and risk of HIV-1 seroconversion among Kenyan men with genital ulcers. AIDS. 2001;15(5):635–639. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumwenda NI, Taha TE, Hoover DR, Markakis D, Liomba GN, Chiphangwi JD, et al. HIV-1 incidence among male workers at a sugar estate in rural. Malawi JAIDS. 2001;27:202–208. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200106010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, Gangakhedkar RR, Brookmeyer RS, Divekar AD, et al. Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India. Lancet. 2004;363:1039–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaffer D, Bautista C, Sateren W, Sawe F, Kiplangat S, Miruka A, et al. The protective effect of circumcision on HIV incidence in rural low-risk men circumcised predominantly by traditional circumcisers in Kenya: Two-year follow-up of the Kericho Cohort Study. JAIDS. 2007;45:371–379. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318095a3da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill BA. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proc Royal Med Soc of Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollinger LA, Stover J, Musuka G, Fidzani B, Moeti T, Busang L. The cost and impact of male circumcision on HIV/AIDS in Botswana. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO/UNAIDS. New data on male circumcision and HIV prevention: Policy and programme implications. Montreux: WHO/UNAIDS Technical Consultation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegfried N, Muller M, Volmink J, Deeks J, Egger M, Low N, et al. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003:CD003362. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Westercamp N, Bailey RC. Acceptability of Male Circumcision for Prevention of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:341–355. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9169-4. This paper reports a systematic review of the literature on acceptability of male circumcision for HIV prevention. The mostly qualitative research reviewed shows considerable evidence that men and women find male circumcision acceptable if it is safe, not overly painful, and effective at preventing STI and HIV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruan Y, Qian HZ, Li D, Shi W, Li Q, Liang H, et al. Willingness to be circumcised for preventing HIV among Chinese men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 May;23(5):315–21. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Begley EB, Jafa K, Voetsch AC, Heffelfinger JD, Borkowf CB, Sullivan PS. Willingness of men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States to be circumcised as adults to reduce the risk of HIV infection. PLoS ONE. 2008 Jul 16;3(7):e2731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngalande RC, Levy J, Kapondo C, Bailey R. Acceptability of Male Circumcision for Prevention of HIV Infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muula AS. Male Circumcision to Prevent HIV Transmission and Acquisition: What Else do We Need to Know? AIDS Behav. 2007;11:357–363. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruyn G, Martinson NA, Nkala BD, Tshabangu N, Shilaluka G, Kublin J, Corey L, Gray GE. Uptake of male circumcision in an HIV vaccine efficacy trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 May 1;51(1):108–10. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a03622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink KS, Carson CC, DeVellis RF. Adult circumcision outcomes study: effect on erectile function, penile sensitivity, sexual activity and satisfaction. J Urol. 2002 May;167(5):2113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masood S, Patel HR, Himpson RC, Palmer JH, Mufti GR, Sheriff MK. Penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction after circumcision: are we informing men correctly? Urol Int. 2005;75(1):62–6. doi: 10.1159/000085930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim D, Pang MG. The effect of male circumcision on sexuality. BJU Int. 2007 Mar;99(3):619–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06646.x. Epub 2006 Nov 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krieger JN, Mehta SD, Bailey RC, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Parker C, Moses S. Adult male circumcision: effects on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Kisumu, Kenya. J Sex Med. 2008 Nov;5(11):2610–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00979.x. Epub 2008 Aug 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peltzer K, Nqeketo A, Petros G, Kanta X. Traditional circumcision during manhood initiation rituals in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a pre-post intervention evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2008 Feb 19;8:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: Implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Current HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. This review of behavioral risk compensation provides a theoretical basis for expecting reductions in condom use among men who undergo male circumcision for HIV prevention The paper also makes the important conceptual distinction between risk compensation and behavioral disinhibition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattson CL, Campbell RT, Bailey RC, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Moses S. Risk compensation is not associated with male circumcision in Kisumu, Kenya: A multi-faceted assessment of men enrolled in a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2008;6:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agot KE, Kiarie JN, Nguyen HQ, Odhiambo JO, Onyango TM, Weiss NS. Male circumcision in Siaya and Bondo districts, Kenya: Prospective cohort study to assess behavioral disinhibition following circumcision. JAIDS. 2007;44:66–70. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242455.05274.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey RC, Muga R, Poulussen R, Abicht H. The acceptability of male circumcision to reduce HIV infections in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2002;1:27–40. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warner L, Ghanem KG, Newman DR, Macaluso M, Sullivan PS, Erbelding EJ. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection among heterosexual African American men attending Baltimore sexually transmitted disease clinics. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(1):59–65. doi: 10.1086/595569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds G, Latimore A, Fisher D. Heterosexual Anal Sex Among Female Drug Users: U.S. National Compared to Local Long Beach, California Data. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:796–805. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cain D, Jooste S. Heterosexual Anal Intercourse among Community and Clinical Settings in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Inf. 2009 doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.035287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kigozi G, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Moulton LH, Chen MZ, et al. The safety of adult male circumcision in HIV-infected and uninfected men in Rakai, Uganda. PLoS Med. 2008 Jun 3;5(6):e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millett GA, Ding H, Lauby J, Flores S, Stueve A, Bingham T, Carballo-Dieguez A, Murrill C, Liu KL, Wheeler D, Liau A, Marks G. Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities. JAIDS. 2007 Dec 15;46(5):643–50. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b834d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH. Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1674–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connolly C, Simbayi LC, Shanmugam R, Nqeketo A. Male circumcision and its relationship to HIV infection in South Africa: results of a national survey in 2002. S Afr Med J. 2008 Oct;98(10):789–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickson NP, van Roode T, Herbison P, Paul C. Circumcision and risk of sexually transmitted infections in a birth cohort. J Pediatr. 2008 Mar;152(3):383–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.07.044. Epub 2007 Oct 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brooks R, Etzel M, Klosinski L, Leibowitz A, Sawires S, Szekeres G, Weston M, Coates TJ. Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Looking to the Future. AIDS Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9523-4. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawires SR, Dworkin SL, Fiamma A, Peacock D, Szekeres G, Coates TJ. Male circumcision and HIV/AIDS: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):708–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]