Abstract

Background

Older age has historically been an adverse prognostic factor in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The impact of age relative to that of other prognostic factors on the outcome of patients treated in recent trials is unknown.

Methods

Clinical outcome and causes of treatment failure of 351 patients enrolled on three consecutive protocols for childhood AML between 1991 and 2008 were analyzed according to age and protocol.

Results

The more recent protocol (AML02) produced improved outcomes for 10- to 21-year-old patients compared to 2 earlier studies (AML91 and 97), with 3-year rates of event-free survival (EFS), overall survival (OS) and cumulative incidence of refractory leukemia or relapse (CIR) for this group similar to those of 0- to 9-year old patients: EFS, 58.3% ± 5.4% vs. 66.6% ± 4.9%, P=.20; OS, 68.9% ± 5.1% vs. 75.1% ± 4.5%, P=.36; cumulative incidence of refractory leukemia or relapse, 21.9% ± 4.4%; vs. 25.3% ± 4.1%, P=.59. EFS and OS estimates for 10–15-year-old patients overlapped those for 16–21-year-old patients. However, the cumulative incidence of toxic death was significantly higher for 10- to 21-year-old patients compared to younger patients (13.2% ± 3.6 vs. 4.5% ± 2.0%, P=.028).

Conclusion

The survival rate for older children with AML has improved on our recent trial and is now similar to that of younger patients. However, deaths from toxicity remain a significant problem in the older age group. Future trials should focus on improving supportive care while striving to develop more effective antileukemic therapy.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, age, pediatrics, adolescents, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

The recognition that cancer survival rates in adolescents have not improved as dramatically as those in younger children1,2 has led to a growing interest in the field of adolescent and young adult oncology.3,4 Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 9 study show that survival rates of younger children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) increased considerably from the 1980s to the 1990s, whereas the corresponding rates for older children improved only modestly.1 Similarly, we previously found that among children and adolescents with AML treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, survival rates improved between the 1980s and the 1990s for patients younger than 10 years but not for those aged 10–21 years.5 Among those treated in the 1990s, survival was significantly worse for older patients.5

Our recently reported study for children and adolescents with newly diagnosed AML (AML02; 2002–2008) yielded 3-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) estimates of 63% and 71%, respectively,6 indicating substantial gains in outcome compared to our previous trial (AML97; 1997–2002), with corresponding estimates of 44% and 50%.7 We attributed this improvement to the use of risk-adapted therapy based on sequential measurements of minimal residual disease as well as to vigilant supportive care, including the use of prophylactic antimicrobials. In the context of these changes in treatment strategy, we reassessed the effect of age on outcome, with additional focus on the adolescent age group.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with AML who were 21 years old or younger and enrolled on one of 3 consecutive St. Jude AML protocols (AML91,8 AML97,7 and AML026) were included in these analyses. Briefly, AML918 included 1 or 2 courses of cladribine, 2 courses of DAV (daunorubicin, 30 mg/m2/day by continuous infusion on days 1–3; cytarabine, 250 mg/m2/day by continuous infusion on days 1–5; etoposide, 200 mg/m2/day by continuous infusion on days 4 and 5), and allogeneic or autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The AML977 trial consisted of one course of cladribine + cytarabine, 2 courses of DAV, and subsequent allogeneic HSCT, autologous HSCT, or chemotherapy. AML026 was a randomized trial of high-dose cytarabine (3 g/m2 every 12 hours on day 1, 3, and 5) or low-dose cytarabine (100 mg/m2 every 12 hours on days 1–10), plus daunorubicin (50 mg/m2 on days 2, 4, and 6) and etoposide (100 mg/m2 on days 2–6) given as Induction I. Induction II consisted of low-dose cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide alone or in combination with gemtuzumab ozogamicin. Post-remission therapy included allogeneic HSCT or chemotherapy, based on the risk of relapse.

Patients with Down syndrome, acute promyelocytic leukemia, secondary AML, or biphenotypic leukemia were excluded. The protocols were approved by the institutional review boards, and written informed consent and assent, as appropriate, were obtained for all patients.

Statistical Methods

OS was defined as the time elapsed from study enrollment to death, with those still living censored at last follow-up. EFS was defined as the time elapsed from study enrollment to induction failure (refractory leukemia after two courses of therapy), withdrawal from the study, relapse, secondary malignancy, or death, with those living and event-free censored at last follow-up. In analyses of cumulative incidence of induction failure and relapse, withdrawal from the study, death, and secondary malignancy were considered to be competing events. In analyses of cumulative incidence of toxic death, induction failure, relapse, and secondary malignancy were considered to be competing events. For patients treated on AML02, the duration of each course of therapy was defined as the time elapsed from the start date of that course of therapy to the start date of the subsequent course of therapy.

The Kaplan-Meier method9 was used to estimate the probability of OS and EFS, and standard errors were determined by the method of Peto and Pike.10 Survival comparisons were made by performing the Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test with permutation P values determined by 10,000 Monte Carlo simulations. Gray’s method was used to estimate and compare the cumulative incidences of infection, induction failure and relapse, and toxic death.11 The association of age group with duration of treatments was assessed using the exact Kruskal-Wallis test with Monte Carlo simulations. The association of age with duration of treatments was assessed using Spearman correlation. All analyses were performed by using SAS software Windows version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software Windows version 2.9.0.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Among the 351 patients with de novo AML who were enrolled on the AML91, AML97, and AML02 protocols, 150 were 10 to 21 years old (Table 1). The distributions of FAB subtype (P < .001), cytogenetic group (P < .0001), and study protocol (P = .02) differed significantly among age groups. FAB M5 and M7 subtypes and 11q23 abnormalities were less common, whereas M2 subtype and t(8;21) were more common, among 10 to 21 year old patients.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Clinical Features | Age Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Clinical Features | 0–9 years | 10–21 years | Two-sided P Values# |

| Gender | Male | 98 | 81 | .334 |

| Female | 103 | 69 | ||

| Race | White | 137 | 103 | .408 |

| Black | 37 | 35 | ||

| Other | 17 | 9 | ||

| Hispanic | 9 | 3 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | ||

| WBC | < 50 | 154 | 105 | .178 |

| ≥ 50 | 47 | 45 | ||

| FAB | Unknown | 2 | 6 | |

| M0 | 4 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 20 | 26 | .055 | |

| M2 | 28 | 47 | .0001 | |

| M4 | 42 | 39 | ||

| M5 | 61 | 27 | .009 | |

| M6 | 1 | 2 | ||

| M7 | 43 | 2 | <.0001 | |

| Cytogenetics | Unknown | 4 | 2 | |

| t (9;11) | 23 | 12 | ||

| t (8;21) | 21 | 32 | .006 | |

| Other 11q23 | 39 | 5 | <.0001 | |

| inv (16) | 18 | 18 | ||

| Normal | 45 | 48 | .051 | |

| Miscell | 51 | 33 | ||

| Study | AML91 | 50 | 20 | .020 |

| AML97 | 40 | 38 | ||

| AML02 | 111 | 92 | ||

Abbreviations: FAB, French-American-British classification; WBC, white blood cell.

Exact Chi-square test

Effects of Treatment Protocol on Outcome

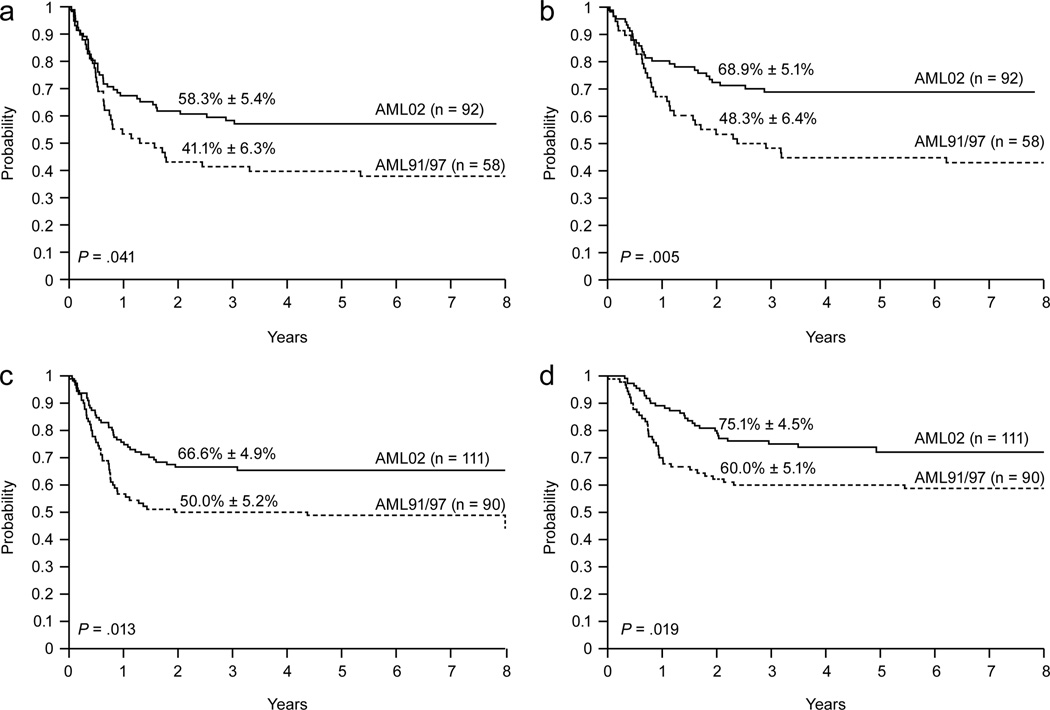

Three-year EFS estimates were significantly higher for 10–21 year old patients who received AML02 therapy (n = 92) than for those treated on AML91 or 97 (n = 58): 58.3% ± 5.4% vs. 41.4% ± 6.3%, P = .041, Fig. 1a; OS estimates were also significantly higher: 68.9% ± 5.1% vs. 48.3% ± 6.4%, P = .005, Fig. 1b. These improvements were paralleled by correspondingly lower rates of induction failure and relapse: 3-year estimates, 21.9% ± 4.4% for AML02 vs. 37.9% ± 6.5% for AML91 and 97, P = .039.

Figure 1.

Event-free survival (a) and overall survival (b) of patients 10 to 21 years old according to treatment protocol. Event-free survival (c) and overall survival (d) of patients 1 to 9 years old according to treatment protocol.

The improvement in outcome obtained in AML02 extended to patients less than 10 years old: 3-year EFS and OS estimates were significantly higher in AML02 (n = 111) than in AML91 or 97 (n = 90): EFS, 66.6% ± 4.9% vs. 50.0% ± 5.2%, P = .013, Fig. 1c; OS, 75.1% ± 4.5% vs. 60.0% ± 5.1%, P = .019, Fig. 1d; 3-year cumulative incidence of induction failure or relapse estimates were lower: 25.3% ± 4.2% vs. 40.0% ± 5.2%, P = .025.

In contrast to the improvements in EFS, OS, and relapse rates observed in AML02, there was only a modest decrease in the cumulative incidence of toxic death among patients treated on AML02 (8.4% ± 2.0%) compared to that of patients treated on the earlier studies (12.2% ± 2.7%, P = .18). For patients 10–21 years old, the 3-year cumulative incidence of toxic death was 13.2% ± 3.6% on AML02, compared to 19.0% ± 5.2% on the earlier studies (P = .23). For patients less than 10 years old, the rates of toxic death were 4.5% ± 2.0% on AML02 and 7.8% ± 2.8% on AML 91/97, P = .33.

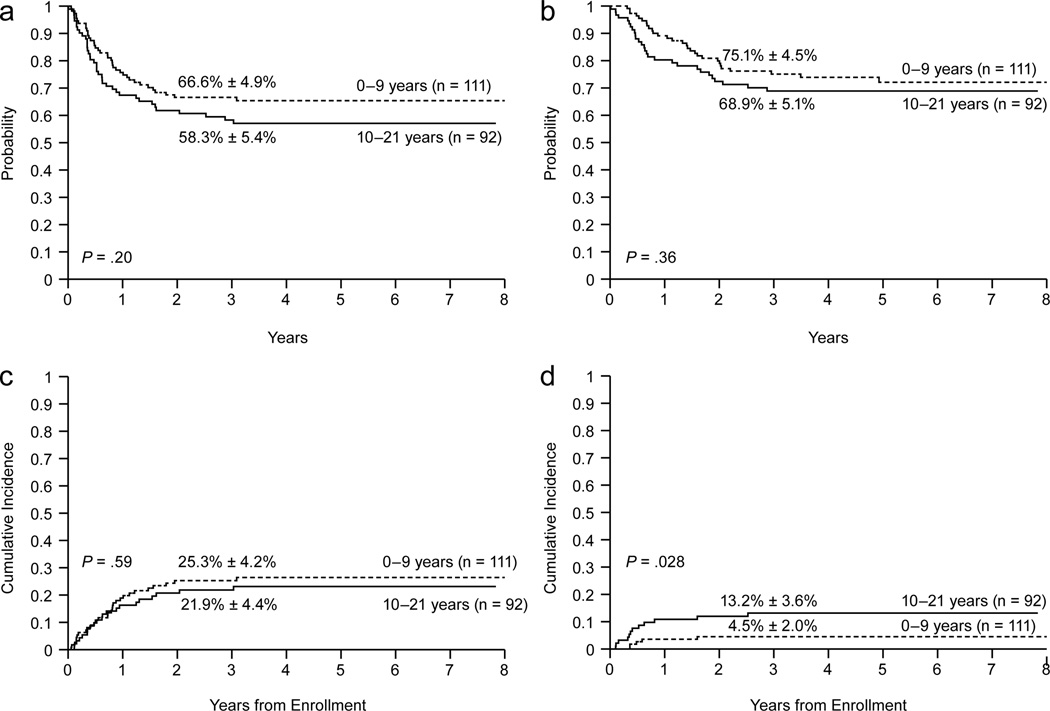

Comparisons Between Age Groups in AML02

Among the patients enrolled on AML02, there was no significant difference in EFS between those who were 10–21 years at diagnosis (n = 92) and younger patients (n = 111): 3-year estimates, 58.3% ± 5.4% vs. 66.6% ± 4.9%, P = .20 (Fig. 2a and Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant difference in OS or cumulative incidence of induction failure or relapse between the age groups: 3-year estimates, 68.9% ± 5.1% vs. 75.1% ± 4.5%, P = .36, and 21.9% ± 4.4% vs. 25.3% ± 4.2%, P = .59, respectively (Figs. 2b and 2c and Table 2). In a competing risk regression model that treated age as continuous variable, older age was not associated with induction failure or relapse (HR, 0.984; 95% CI, 0.944 to 1.027; P = 0.46).

Figure 2.

Outcomes according to age for patients treated on AML02. (a) Event-free survival, (b) Overall survival, (c) Cumulative incidence of refractory leukemia or relapse, (d) Cumulative incidence of toxic death.

Table 2.

Outcome and causes of failure among patients treated on AML02

| Ages 0–9 (n=111) |

Ages 10–21 (n=92) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year EFS | 66.6% ± 4.9% | 58.3% ± 5.4% | P = .20 |

| 3-year OS | 75.1% ± 4.5% | 68.9% ± 5.1% | P = .36 |

| 3-year CI relapse or refractory leukemia | 25.3% ± 4.1% | 21.9% ± 4.4% | P = .59 |

| 3-year CI of toxic death | 4.5% ± 2.0% | 13.2% ± 3.6% | P =.028 |

| Treatment failures | |||

| Relapse or refractory leukemia | 29 | 21 | |

| Toxic deaths | 5 | 12 | |

| Infection | 3 | 9 | |

| Hemorrhage | 1 | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | |

| Total deaths | 29 | 28 | |

EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, cumulative incidence

In contrast to the similarities in EFS, OS, and cumulative incidence of induction failure or relapse between the two age groups, the 3-year cumulative incidence of toxic death of 13.2% ± 3.6% for 10–21 year old patients was significantly higher than the 4.5% ± 2.0% for younger patients (P =.028, Fig. 2d and Table 2). This difference in toxic death rates according to age was also observed among patients treated on the AML91 or 97 protocols (19.0% ± 5.2% for 10–21 year old patients compared to 7.8% ± 2.8% for younger patients (P =.023).

Within AML02, a competing risk regression model that included FLT3 status (ITD vs. other) and karyotype (favorable vs. other) revealed that the cumulative incidence of toxic death of patients 10 to 21 years old differed significantly from that of patients 0 to 9 years old (HR, 3.303; 95% CI, 1.06 to 10.30; P = .039). When age was treated as a continuous variable, older age was marginally associated with an increased risk of toxic death after adjusting for FLT3 status and karyotype (HR = 1.111; 95% CI, .997 to 1.237; P = 0.057).

Among the 17 patients who died from causes other than refractory leukemia or relapse, 12 succumbed to infection due to bacterial (6), fungal (3), and viral (3) pathogens. Twelve patients were 10–21 years old; the causes of death in this age group included infection (9), hemorrhage (2), and encephalopathy of unknown cause (1). Of the remaining 5 patients who died of toxicity, 4 were infants, who died from infection (2), hemorrhage (1), and narcotic overdose (1). To investigate potential causes for the increased risk of infection among older patients, we analyzed the length of each course of therapy according to age group. The duration of consolidation I was significantly longer for 10–21 patients: mean (range) 35 days (22–149) vs. 32 days (21–86) for younger patients (P = .011). The difference in duration was even greater for consolidation II: 49 days (35–135) vs. 41 days (22–69) vs P < .001).

Finally, we performed additional analyses of patients who were 16–21 years old to determine if their outcome differed from that of children 10–15 years old. The 3-year EFS and OS estimates were nearly identical between 10–15-year-old patients (EFS, 59.2% ± 6.1%; OS, 69.6% ± 4.7%) and 16–21-year-old patients (EFS, 56.7% ± 9.6%; OFS, 67.2% ± 9.3%). In addition, the cumulative incidence of refractory leukemia or relapse (23.5% ± 5.4% and 17.9% ± 7.4%) and the cumulative incidence of toxic death (12.5% ± 4.2% and 14.8% ± 7.1%) were similar between the 10–15-year-old and 16–21-year-old age groups.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the impact of recent advances in treatment on the outcome of 10–21 years old patients with pediatric AML. The results of this study demonstrate that overall survival rates increased by approximately 20% and relapse rates decreased by about 15% for patients in this age group who were treated from 2002–2008, as compared to those who were treated from 1991–2001. In addition, rates of OS, EFS, and cumulative incidence of relapse or refractory disease for older patients treated on AML02 were not significantly inferior to those of younger patients. Among patients treated on AML02, the only age-associated difference in outcome was the increased incidence of toxic deaths among patients 10–21 years old. Treatment-related mortality was higher among 10–21-year-old patients than among 0–9-year-old patients on both the older (AML91 and 97) and more recent (AML02) trials. During the conduct of AML02, we implemented a series of supportive care measures among patients treated at our institution.12 Although we demonstrated that the use of prophylactic vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and voriconazole significantly reduced the incidence of bacteremia and length of hospitalization, this measure did not appear to impact treatment-related mortality.12 It should be noted, however, that these supportive care guidelines were introduced approximately 2 years after accrual to the study began and were not implemented at all sites. It is conceivable that strict adherence to these guidelines may affect toxic deaths in future trials. Nevertheless, in AML02, toxic deaths, primarily from infection, still occurred in more than 10% of these patients.

Results of our previous study demonstrated that age was an independent prognostic factor in childhood AML, with lower EFS and OS rates and a higher cumulative incidence of relapse or refractory disease in patients aged at least 10 years.5 In that study, which included patients who were treated from 1983 through 2002, the effect of age was seen primarily among patients treated from 1990 through 2002, during which time the outcome improved for younger children but not for older children. Similarly, in an analysis of patients with AML treated on 6 trials from 1993 to 2004, Creutzig et al.13 reported that older age was an independent negative predictor of outcome. These investigators found that patients aged 2–12 years had higher rate of complete remission and lower relapse rates than did other age groups. In addition, there was a trend toward higher treatment-related mortality with increasing age.13 In a study of AML patients treated from 1986 to 1999, Horibe et al.14 showed that children 1–9 years of age had the highest EFS rate (43%), with lower EFS rates reported for older age groups (34% for 10–15-year-old patients, 32% for 15–19-year-old patients, and 26% for those 20–29-years-old).

A variety of reasons have been set forth to explain the inferior survival rates for adolescents and young adults with cancer, including delays in diagnosis, insurance barriers, low rates of enrollment on clinical trials, poor adherence, high-risk biological features, and increased treatment-related toxicity.2,3 Most of these factors, however, do not apply to the older patients analyzed in the present study, all of whom were enrolled in clinical trials for AML, and received the planned protocol-directed therapy regardless of insurance status. Poor adherence is unlikely to be a major issue in AML because all chemotherapy is given intravenously, with most patients receiving their therapy in the inpatient setting. Our study shows that, in the context of intensive risk-based therapy with sequential minimal residual disease monitoring, adolescents with AML no longer experience inferior survival rates.

There is currently no clear explanation for the increased toxicity of AML treatment for older pediatric patients, which has been previously reported.15–18 Adolescents with AML typically do not have the co-morbidities associated with toxicity in older adults and are rarely on concomitant medications that may increase toxicity. It is possible that subtle differences in immunologic function, coagulation, or pharmacokinetics may contribute to the toxicity differences. In addition, the increased length of each course of consolidation therapy in older patients makes prolonged neutropenia a potential contributing factor in the increase in infection-related deaths. Conceivably, cumulative hematologic toxicity could be greater in older patients because of multiple factors, including slower clearance of chemotherapeutic agents, decreased bone marrow reserve, or reduced telomere length in hematopoietic precursors. Although the routine use of granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) does not decrease the risk of infectious complications or affect outcome in children with AML,19 its effect in the adolescent age group remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we have shown that the outcome of adolescents with AML has improved in the recent treatment period and that the rates of relapsed and refractory disease in adolescents are similar to those in younger patients. Current trials must focus on elucidating the causes of increased toxicity and improving supportive care for older children with AML.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant P30 CA021765-30 from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Ching-Hon Pui is an American Cancer Society Professor.

The authors thank Cherise Guess for expert editorial review, Kathy Jackson and Heidi Clough for data collection, and Julie Groff for preparing the figures.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest and no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleyer A. Young adult oncology: the patients and their survival challenges. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:242–255. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood WA, Lee SJ. Malignant hematologic diseases in adolescents and young adults. Blood. 2011;117:5803–5815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-283093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sender LS. A new journal to improve care for adolescent and young adult oncology patients and survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1:1–2. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2011.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razzouk BI, Estey E, Pounds S, et al. Impact of age on outcome of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from 2 institutions. Cancer. 2006;106:2495–2502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Dahl G, et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: results of the AML02 multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:543–552. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubnitz JE, Crews KR, Pounds S, et al. Combination of cladribine and cytarabine is effective for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: results of the St Jude AML97 trial. Leukemia. 2009;23:1410–1416. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krance RA, Hurwitz CA, Head DR, et al. Experience with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in previously untreated children with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2804–2811. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35:1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurt B, Flynn P, Shenep JL, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics reduce morbidity due to septicemia during intensive treatment for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2008;113:376–382. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creutzig U, Buchner T, Sauerland MC, et al. Significance of age in acute myeloid leukemia patients younger than 30 years: a common analysis of the pediatric trials AML-BFM 93/98 and the adult trials AMLCG 92/99 and AMLSG HD93/98A. Cancer. 2008;112:562–571. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horibe K, Tsukimoto I, Ohno R. Clinicopathologic characteristics of leukemia in Japanese children and young adults. Leukemia. 2001;15:1256–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sung L, Lange BJ, Gerbing RB, Alonzo TA, Feusner J. Microbiologically documented infections and infection-related mortality in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:3532–3539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung L, Gamis A, Alonzo TA, et al. Infections and association with different intensity of chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115:1100–1108. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, et al. Early deaths and treatment-related mortality in children undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: analysis of the multicenter clinical trials AML-BFM 93 and AML-BFM 98. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4384–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubnitz JE, Lensing S, Zhou Y, et al. Death during induction therapy and first remission of acute leukemia in childhood: the St. Jude experience. Cancer. 2004;101:1677–1684. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrnbecher T, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, et al. Prophylactic human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after induction therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:936–943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]