Abstract

Norepinephrine and epinephrine signaling is thought to facilitate cognitive processes related to emotional events and heightened arousal, however, the specific role of epinephrine in these processes is less known. To investigate the selective impact of epinephrine on arousal and fear-related memory retrieval, mice unable to synthesize epinephrine (phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase knockout, PNMT-KO) were tested in context and cued fear conditioning. To assess the role of epinephrine in other cognitive and arousal-based behaviors these mice were also tested for acoustic startle, prepulse inhibition, novel object recognition and open field activity. Our results show that compared to wild-type (WT) mice, PNMT-KO mice displayed reduced context fear but normal cued fear. Mice exhibited normal memory performance in the short-term version of the novel object recognition task suggesting PNMT mice exhibit more selective memory effects on highly emotional and/or long term memories. Similarly, open field activity was unaffected by epinephrine deficiency, suggesting differences in freezing are not related to changes in overall anxiety or exploratory drive. Startle reactivity to acoustic pulses was reduced in PNMT-KO mice while prepulse inhibition was increased. These findings provide further evidence for a selective role of epinephrine in contextual fear learning, and support its potential role in acoustic startle.

Keywords: PNMT, epinephrine, conditioned fear, memory, acoustic startle, prepulse inhibition, arousal

Introduction

Emotionally arousing experiences tend to be recalled better than neutral ones. This phenomenon is due in part to the memory-enhancing effect of adrenergic catecholamines (norepinephrine-NE and epinephrine-E) including both central and peripheral actions (Cahill et al., 1994; McGaugh and Roozendaal, 2002; McIntyre and Roozendaal, 2007; McIntyre et al., 2011). A large body of evidence suggests that noradrenergic receptor signaling enhances memory consolidation and retrieval in laboratory animals, as well as humans (Gold and Van Buskirk, 1975, 1978; Cahill et al. 1994; Clayton and Williams, 2000; Izquierdo et al., 2002; Nordby et al., 2006). Specific blockade of beta adrenergic receptors shortly after either appetitive or aversive learning paradigms disrupts short- and long-term memory consolidation in rodents and humans (Introini-Collison et al., 1992; Nielson and Jensen, 1994; Cahill et al., 2000; Cahill and Alkire, 2003; King and Williams, 2009). Beta blockers also disrupt memory if administered before memory retrieval (Murchison et al., 2004). Conversely, systemic or central administration of NE/E or their receptor agonists during consolidation or retrieval enhances performance across tasks of spatial- or object-related memory, conditioned fear and inhibitory avoidance behavior (Gold and Buskirk, 1975; Sternberg et al., 1986; Introini-Collison et al., 1992; Torras-Garcia et al., 1997; Williams et al. 1998; Murchison et al., 2004). Taken together these studies support a modulatory role of NE/E signaling in memory formation and recall.

Several neural substrates are implicated in noradrenergic receptor signaling effects on memory, including the basolateral amygdala (Ferry et al., 1999; McGaugh, 2004; Roozendaal et al., 2006). Noradrenergic transmission in the amygdala mediates the memory modulating effects of E, corticosterone and other neurotransmitter systems (Gold and Buskirk, 1978; Quirarte et al., 1997, 1998; McGaugh and Roozendaal, 2002; de Quervain et al., 2007). Neuroanatomical and physiological data also support a modulatory role of NE/E on memory, with extensive noradrenergic projections to the hippocampus, extended amygdala and prefrontal cortex in several mammalian species, including humans (Hokfelt, 1974; Swanson and Hartman, 1975; Armstrong et al., 1982; Gaspar et al., 1989; Samson et al., 1990; Roder and Ciriello, 1993). Novelty or emotionally arousing events induce a significant release of NE/E in these circuits (McCarty and Gold, 1981; Kitchigina et al., 1997; Rosario and Abercrombie, 1999; McIntyre et al., 2002; Geracioti et al., 2008). Accordingly, an extensive literature suggests that highly emotional, novel or salient stimuli are more memorable via their ability to induce NE/E neurotransmission (Nielson and Jensen, 1994; Okuda et al., 2004; McIntyre and Roozendaal, 2007; Schwabe et al., 2009).

It is not clear how much of a role E specifically plays in memory formation, because of the difficulty in disentangling NE from E effects. Since their synthesizing pathways (from tyrosine to NE) and their receptor repertoire are mostly overlapping, the final conversion step from NE to E by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) allows specific targeting of E to dissect these two transmitter systems. Mice with PNMT knockout have normal synthesis of NE but are unable to convert NE to E in the periphery and in the central nervous system, resulting in a complete loss of E. Although there have been some reports suggesting that E is necessary for stress effects on learning and other behaviors, these studies have either been based on full adrenalectomy, which confounds effects of E with loss of other critical hormones (e.g. corticosterone) or via a null mutation of DBH, confounding loss of E with concurrent loss of NE (Borrell et al. 1983; Roozendaal et al. 1998; Murchison et al. 2004; Spanswick and Sutherland 2010). As adrenergic receptors have affinity to both E and NE, pharmacological studies are limited to dissect the specific role of these transmitter/hormone systems in emotional memory formation. Although, the expression and release of E is more restricted in the brain compared to NE (Hokfelt et al., 1974; Armstrong et al., 1982), PNMT-positive axonal distributions and E release from these nuclei are significant in the amygdala (Asan, 1993; Roder and Ciriello, 1993). In addition, peripheral E from the adrenals can induce significant noradrenergic release in the hippocampus, mediating the effect of arousal on memory processes (Miyashita and Williams, 2004). Based on this literature we hypothesized that E deficient mice would exhibit disruptions in fear learning and abnormalities in arousal behaviors such as startle reactivity. Thus in the present study we sought to determine the contribution of E to the regulation of acoustic startle and retrieval of highly arousing memories in mice lacking the ability to synthesize E. We also examined the mice for short-term memory performance in the novel object recognition task to determine if E deficiency results in a deficit of memory acquisition or short-term memory retrieval of slightly arousing stimuli. Finally, we also assessed open field activity to differentiate between fear memory changes and general changes in anxiety and behavioral activity.

Methods

Subjects

Male wild-type (WT, n=11) and PNMT-KO (n=10) mice on a C57BL/6J background were used in the present study (for original description of PNMT-KO mutation see Bao et al., 2007). Mice were housed in a temperature and humidity-controlled room with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08:00 h) and food and water available ad libitum. Behavioral testing started at 4–5 months of age with a brief assessment of locomotor activity in a novel environment (“Day 0”) followed by context and cue dependent conditioned fear testing on Day 8–10, novel object recognition task on Day 29 and acoustic startle assessment on Day 41. All behavioral testing occurred between 10:00 and 16:00 h and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as approved by the University of California, San Diego.

Open field test

Open field activity was assessed in an open arena (40 × 40 × 40 cm) with light illumination from above (850 lux for details see Dulawa et al., 1999). Subjects were placed on the periphery and their locomotor activity was recorded for 45 min and analyzed using Ethovision tracking software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). The chambers were cleaned thoroughly with water between testing sessions. Total distance moved, center (25 × 25 cm) duration and entries were considered in the analysis.

Conditioned fear test

Conditioning apparatus

The procedure used in the fear conditioning experiment was adapted from previous studies (for a detailed description, see Valentinuzzi et al., 1998; Gresack et al., 2010). Briefly, electric foot shocks were delivered in acrylic chambers (25 cm wide × 18 cm high × 21 cm deep, San Diego Instruments) consisting of 32 stainless steel rods wired to a shock generator (San Diego Instruments). Presentation of unconditioned (US: scrambled foot shock) and conditioned (CS: auditory tone, Sonalert pure tone generator) stimuli was controlled by computer. Sixteen infrared photobeams surrounding the chamber were used to continuously detect the mouse's movements. The latencies and numbers of beam interruptions were recorded and used for determination of conditioned fear (freezing) response. Freezing was determined using an automated method that relied upon the latency to break the infrared beams. The tests were divided into 5-s epochs and the latency to break the first of three photobeams within each 5-s interval was recorded. If a mouse took longer than 1 s to break the first beam, then an instance of freezing was scored. The number of 5-s intervals during which an instance of freezing was observed was divided by the total number of 5 s intervals and multiplied by 100 to determine the % freezing. A correlation for percent freezing obtained using hand scoring vs. automated methods was previously calculated and was found to be Pearson’s r = 0.90, p < 0.0001 (Gresack et al. 2010).

Experimental procedure

On the day of conditioning, mice were transported in their home cages to a room located adjacent to the testing room. After a 60 min habituation period, mice were placed in the conditioning chamber. After an acclimation period (2 min), mice were presented with a tone (CS: 75 dB, 4 kHz) for 20 s that co-terminated with a foot shock (US: 1 s, 0.5 mA). A total of three tone-shock pairings were presented with an inter-trial interval of 40 s. Freezing was measured during shock presentations and for 40 s after shock. Mice were replaced in their home cage 40s after the final shock. We have found these moderate shock parameters allow us to detect both increases and decreases in fear conditioned behavior. The chambers were cleaned with water after each session. Twenty-four hours later, subjects were re-exposed to the conditioning chamber for a context fear retention test. The habituation period and features of the chamber were identical to those used during conditioning. This test lasted 8 min during which time no shocks or tones were presented and freezing was scored for the duration of the session. Twenty-four hours after the context fear retention test, mice were tested for CS-induced fear retention. The contexts of the chambers were altered on several dimensions (tactile, odor, visual) for the tone test in order to minimize generalization from the conditioning context. Specifically, the grid floors were replaced with smooth plastic floors cleaned with peppermint scent between each run. The walls of the chamber were adorned with various geometric shapes. The habituation period was the same as above. After a 5 min acclimation period, during which time no tones were presented, 32 tones were presented for 20s with an inter-trial interval of 5 s. Freezing was scored during and after each tone presentation. Baseline freezing during the acclimation period prior to the tone presentation was also assessed. Subjects were returned to their home cage immediately after termination of the last tone.

Novel object recognition task

To determine if other forms of memory are disrupted in PNMT-KO mice, 3 weeks after the conditioned fear test we tested the mice for short term novel object recognition as described previously (Ali et al. 2011). The novel object recognition task was performed in an open arena (60 × 60 cm) using two object types (Lego pyramid and 50 mL plastic conical tube containing gravel) affixed to the floor using Velcro tape in opposing corners of the open field 10 cm away from the walls. Each mouse completed one session that comprised of three successive trials. In trial 1, the habituation phase, the mouse was placed in the center of the empty open field box and allowed to freely explore. During trial 2, the sample phase, two of the same objects were placed in opposite corners of the box and the mouse was allowed to explore the objects. Half of the mice were randomly assigned to either starting with the Lego pyramid or the conical tube as the familiar object. In trial 3, one of the objects was replaced with a new object to assess novel object exploration. Each trial was 5 min; the inter-trial interval (ITI) was 5 min between Trial 1 and 2 and 1 h between Trial 2 and 3. This time point was chosen as performance after a 1 hr delay has previously been associated with hippocampal function in rats (Clark et al. 2000). The mouse was removed from the testing box and placed in a holding cage during the ITIs. The box and the objects were carefully cleaned with water between each trial and cleaned with 70% alcohol at the end of each testing session. Locomotor activity was assessed using Ethovision tracking software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). Object exploration was defined as when the mouse’s nose was within 2 cm of the object. Performance was calculated as the time percentage of novel object preference: the length of time exploring the novel object/the time exploring the novel object + the familiar object.

Acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition assessment

Startle assessment was run 2 weeks after novel object recognition task. Startle chambers (SR-LAB, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) consisted of nonrestrictive Plexiglas cylinders 5 cm in diameter resting on a Plexiglas platform in a ventilated chamber. High-frequency speakers mounted 33 cm above the cylinders produced all acoustic stimuli. Piezoelectric accelerometers mounted under the cylinders transduced movements of the animal, which were digitized and stored by an interface and computer assembly. Beginning at startling stimulus onset, 65 consecutive 1 ms readings were recorded to obtain the peak amplitude of the animal's startle response. A dynamic calibration system was used to ensure comparable sensitivities across chambers as previously described (Risbrough et al. 2009). The house light remained on throughout all testing sessions.

For the acoustic startle sessions, the intertrial interval between stimulus presentations averaged 15 sec (range of 7–23 sec). A 65 dB background was presented continuously throughout the session. Startle pulses were 40 ms in duration, prepulses were 20 ms in duration, and prepulses preceded the pulse by 100 ms (onset-onset). The acoustic startle sessions included 3 blocks. Sessions began with a 5-min acclimation period followed by delivery of 5 each of 120 dB startle pulses. This block is used to allow startle to reach a stable level before specific testing blocks. Then a second block tested response threshold and included 4 each of five different acoustic stimulus intensities: 80, 90, 100, 110 and 120 dB in a pseudorandom order. The third block consisted of 42 trials including twelve each of 120 dB startle pulse intensities and ten each of three different prepulse trials (68, 71 and 77 dB preceding a 120 dB pulse). The session ended with 5 pulses of 120 dB. Prepulse inhibition (PPI) was calculated as percent change compared to 120 dB pulses without prepulse using 120 dB alone trials in the 3rd block. Habituation was measured by comparing the response to 120 dB across the 4 stimulus blocks in the session. The peak startle magnitude during the record window (i.e., 200 msec) was used for all data analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are described as mean±SEM. Open field activities and exploration in the novel object recognition task were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Freezing during fear acquisition and context or cue exposure was analyzed using one-way and repeated measure ANOVA tests. Startle magnitude and %PPI (100-(average startle magnitude in prepulse trial/average startle magnitude to pulse alone trial)*100) were analyzed by two-way ANOVAs with genotype as the between-subject factor and intensity (either of pulse or prepulse) as a within-subject factor. When appropriate, post hoc pairwise comparisons (Student t-test) were also conducted. To exclude the effect of startle magnitude changes on PPI, we also used startle baseline as a covariate in the ANOVA completed on %PPI.

Results

Open field test

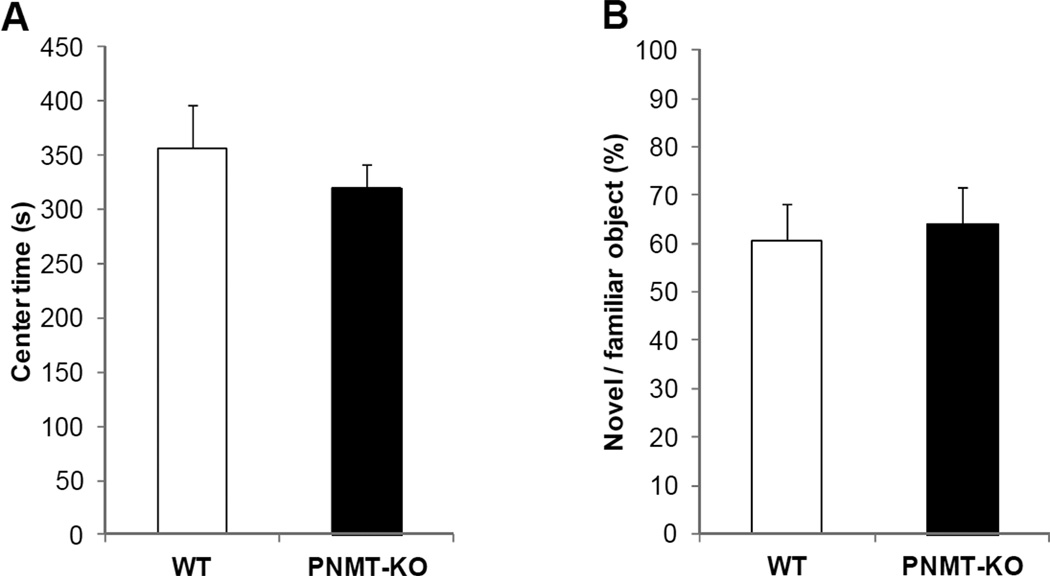

PNMT-KO mice did not show any alteration in spontaneous locomotor activity compared to WT littermates as assessed by total distance traveled, center entries and time spent in the center (Fig.3A, Distance (m) WT=131.48±6.73, KO=133.74±3.06; Center Entries: WT=164.90±10.81, KO=157.44±7.05). To determine if this early exposure period was more sensitive to E deficiency we also examined just the first 5 min of open field exposure separately, but found the same pattern of results across all measures (i.e. no effect of genotype, data not shown).

Fig. 3.

(A) Central activity in the open field arena and (B) novel object preference in the novel object recognition task did not show significant effect of E deficiency. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. See results for additional activity measures.

Conditioned fear test

During fear acquisition, freezing gradually increased with each pairing of the tone cue and footshock during fear conditioning (Fig 1A, Ftime (2,38)=10.172, p<0.001). There was no effect of genotype during acquisition.

Fig. 1.

Conditioned fear test. (A) Footshock-tone cue pairings induced similar increases in freezing levels in PNMT-KO and WT mice after each pairing. (B) During re-exposure to the shock context, PNMT-KO mice froze significantly less compared to WT subjects. (C) PNMT-KO and WT mice exhibited similar freezing responses in an altered context and (D) during the presentation of shock associated auditory cues. *p<0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Re-exposure to the shock context (context fear retention test) induced robust freezing in WT mice but was significantly lower in KO mice (Fig 1B, Fgenotype(1,19)=5.072, p<0.05; Ftime × genotype (3,57)=2.562, p=0.064). Over the 8 min context test WT mice showed a gradual decrease of %freezing over time (Ftime (3,30)=3.951, p<0.05) which was absent in the freezing pattern of PNMT-KO (Ftime (3,27)=1.619, ns).

In contrast, PNMT-KO and WT mice did not differ in time spent freezing in a modified context during the 2 min acclimation period before auditory cue presentation on the next day (Fig 1C). The presentation of shock-associated auditory cues induced a significant increase in %freezing in both groups compared to pre-tone baseline (Fig. 1D, Fcue(2,38)=25.008, p<0.001; Fgenotype(1,19)<1, ns). There was no genotype effect on cued responses (Fgenotype(1,19)<1, ns), when normalized for pretone baseline (cued freezing – pretone baseline; Fgenotype(1,19)=1.030, ns).

Novel object recognition task

Three mice were excluded from the analysis (one WT and two KOs) due to lack of exploration (<1% of time spent exploring the objects during the sampling/testing phases). Both groups preferred to explore the novel object during the test session as novel object preference was significantly different from chance (t=2.363, p=0.015 vs. 50%). Performance did not differ between groups (Fig.3B; time spent exploring objects during the sample phase (sec): WT=5.96±1.47, KO=6.04±2.13).

Acoustic startle and prepulse inhibition

As shown in Fig.2A, startle responses gradually increased with increasing pulse intensity (Fintensity (4,72)=58.113, p<0.001). PNMT-KO mice exhibited a trend for reduced startle reactivity (Fgenotype (1,18)=4.332, p=0.051; Fintensityxgenotype (4,72)=2.850, p<0.052) that was significant at the 110 dB pulse (p<0.012, pair wise comparison). Conversely, PNMT-KO exhibited significant increases in PPI compared to WT mice (Fgenotype (1,18)=9.196, p<0.01; Fig.2B). A covariance analysis with baseline startle (Young et al., 2010) showed that this increase in PPI performance was only partially due to the lowered startle magnitude as PPI tended to be higher in PNMT-KO mice even when accounting for baseline startle magnitude (Fgenotype (1,17)=4.226, p=0.055). No differences in startle habitation between PNMT-KO and WT mice were observed (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A) Acoustic startle response (presented as arbitrary digitized units) was significantly lower in PNMT-KO mice at high sound intensities. (B) Independently from changes of startle magnitude, percent prepulse inhibition was increased in PNMT-KO mice. *p<0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In the present study we examined the effect of E deficiency on behavioral activity, fear conditioning, short-term memory performance and startle reactivity in male mice. PNMT-KO mice exhibited decreased context- but not cued-fear conditioning. These data suggest E deficiency selectively affects contextual fear learning. WT and PNMT-KO mice had similar freezing during fear acquisition, suggesting that pain perception of the shocks and acute fear acquisition were not affected by genotype. PNMT-KO mice showed normal short-term memory retrieval in the novel object recognition task, hence, it is likely that attention and short-term memory acquisition were not affected significantly by E deficiency. Similarly, activity and anxiety-like behavior in the open field were unaltered by E deficiency which also suggests a more specific effect of E on fear learning, specifically to contextual cues. E deficiency also induced decreased startle reaction and increased PPI, supporting a role for E in startle reactivity and sensorimotor gating.

A large body of evidence supports marked differences between the underlying neural mechanisms of context- and cue-dependent memory processes (e.g. involving hippocampus; Sutherland and McDonald, 1990; Phillips and LeDoux, 1992). Present results suggest that context and cue-dependent conditioned fear also differ in adrenergic neurotransmission. This interpretation is supported by previous reports showing that non-selective beta blockers decrease only contextual conditioned fear in rodents and humans (Grillon et al., 2004; Janitzky et al., 2007). Similarly, dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) knockout mice which are unable to synthesize both NE and E, also exhibit reduced contextual- but intact cued-fear learning (Murchison et al., 2004). Similarly to Murchison et al. (2004), we found that freezing in a modified context did not depend on adrenergic neurotransmission. These data suggest that loss of E is sufficient to mimic the contextual fear learning deficits observed in DBH deficient mice, which exhibit loss of both E and NE signaling.

There are three possible actions that could account for the present findings: (1) loss of central adrenergic neurotransmission directly at neural circuits mediating context memory, (2) loss of central and/or (3) peripheral E release with a subsequent change of central NE signaling in these brain regions. Since PNMT shows little or no expression and enzymatic activity in the hippocampus and the amygdala in different species including rodents (Hokfelt et al., 1974; Lew et al., 1977), the significant impact of E loss in these regions is less likely than the other two mechanisms involving NE signaling. In the hippocampus, beta-1 receptor blockade is sufficient to produce contextual fear deficits similar in magnitude to deficits after systemic administration of these drugs (Ji et al., 2003; Murchison et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). Conversely, the beta receptor agonist isoproterenol is able to restore deficient conditioned fear in DBH-KO mice (Murchison et al., 2004). Contextual fear conditioning is also disrupted by intraamygdalar injection of beta blockers, and conversely local administration of NE increases contextual fear consolidation (Liang et al., 1986), although the present context-specific disruption of conditioned fear implicates the more likely involvement of the hippocampus (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992; Maren, 2008). Hence, our data suggest that NE has a strong impact on memory formation and retrieval in hippocampal circuits, likely via beta-1 receptor activation. Although E may not affect amygdalar and hippocampal activity directly, it has a significant influence on locus coeruleus (LC) activity (Holdefer and Jensen, 1987; Miyashita and Williams, 2004). Some previous reports suggested a possible inhibitory role of adrenergic nuclei of the ventral medulla on LC activity via alpha-2 receptors (Cedarbaum and Aghajanian, 1976), however, these effects are questionable as those PNMT inhibitors which lack alpha-2 affinity did not have an effect on LC firing activity (Engberg et al., 1981). In contrast, there are consonant studies showing that peripheral E can increase LC activity (Holdefer and Jensen, 1987), NE concentration in the hippocampus and the amygdala (Williams et al., 1998; Miyashita and Williams, 2004), and in turn, enhance contextual memories in a NE-dependent manner (Borrell et al., 1983; Liang et al., 1986). Peripheral E administration has also been shown to enhance stabilization of LTP in hippocampal neurons over several days, suggesting a molecular mechanism for E-induced increases in memory processes (Korol and Gold, 2008). The current hypothesis suggest that peripheral E acts on beta receptors of the vagal nerve inducing glutamatergic release in the nucleus tractus solitarii, which in turn, stimulates LC and noradrenergic release in the amygdala and the hippocampus (Williams and McGaugh, 1993; Miyashita and Williams, 2004; King and Williams, 2009). Considering the high peripheral concentration of E under highly arousing states, it is tempting to speculate that the lack of peripheral E during shock exposure and/or shock context presentations significantly contributed to impaired fear conditioning in PNMT-KO mice via the above mentioned pathway. Following this logic, peripheral E may exert selective influences on different fear-related memory systems (such as the amygdala and the hippocampus) as cue-dependent conditioned fear was unaffected by E deficiency. Future studies are necessary to clarify such selective catecholaminergic mechanisms (e.g. at the level of the NTS or the forebrain).

Genetic disruption of the PNMT gene results in a chronic deficiency of E and can affect both memory consolidation and retrieval. However, it is unlikely that alteration of fear conditioning is due to generally impaired memory acquisition. PNMT knockout mice performed normally in the novel object recognition task, suggesting that their conditioning deficits are unlikely due to disrupted attention and acquisition processes. An alternate explanation is that E/NE may affect short and long term memory differentially. The present version of this task required short-term (1h) memory retrieval which may be less affected by NE/E transmission and arousal (Izquierdo et al., 1999; Quevedo et al., 2003; Murchison et al., 2004.

PNMT knockout mice also showed a blunted acoustic startle response at high sound intensities suggesting that E may play a role in maximal startle responding. Noradrenergic signaling is well known to affect startle. Administration of the alpha-2 agonist clonidine, which reduces NE release via activation of autoreceptors, reduces both baseline and stress/fear potentiated startle in laboratory animals and humans (Davis et al., 1979; Leaton and Cassella, 1984; Fendt et al., 1994; Kumari et al., 1996; Gresack and Risbrough, 2011). Conversely, pharmacological blockade or genetic disruption of alpha-2 receptors increases startle reactivity (Kehne and Davis, 1985; Morgan et al., 1993; Sallinen et al., 1998; White and Birkle, 2001). Beta receptors play less of a role in startle modulation (Davis, 1980; Leaton and Cassella, 1984; Gresack and Risbrough, 2011). Our data suggest that, in addition to NE, E has a potential modulatory role in acoustic startle response. Interestingly, PNMT-KO mice also have increased PPI, and these changes were largely independent of startle magnitude changes. These data suggest the regulatory role of adrenergic signaling also in sensorimotor gating during these stressful conditions. Recently, enhanced NE neurotransmission was also shown to induce decreased PPI at several brain regions innervated by the locus coeruleus, including the medial prefrontal cortex, bed nucleus of stria terminalis, basolateral amygdala, and the mediodorsal thalamus (Alsene et al., 2011). Based on the above mentioned data, we hypothesize that stressful stimuli induce significant E release (especially in the periphery) which in turn increases NE release in these brain regions, resulting in increased startle reactivity and decreased prepulse inhibition. It is important to note startle reflex was assessed after fear conditioning, which may have had long-term effects on anxiety-like behavior that could interact with E deficiency. Although we cannot rule this possibility out, we believe that it is not likely, as we have found that conditioned fear training in a separate context does not affect subsequent startle responding (e.g. startle is only increased after fear conditioning to the startle boxes themselves) (Risbrough et al. 2009).

In conclusion, the lowered startle reactivity and fear response of PNMT knockout mice support a facilitating role of E in the encoding of emotionally arousing events and its possible contribution to excessive arousal levels associated with fearful experiences. Beyond the well-documented role of E in acute sympathetic activation and acute stress response such as modulation of arousal, there is support for a significant role in long term stress adaptation, emotional memory encoding. In addition, there is evidence for a role of E (and NE) in the elevation of arousal and fear memory under pathological conditions, e.g. in PTSD (Morgan et al., 1995; O`Donnel et al., 2004). In this respect, our data support the potential role of adrenergic catecholamines in the pathogenesis of PTSD (fear memory and startle reaction) and the possible treatment applications of beta adrenergic drugs, which showed some preliminary efficacy as adjunct treatments of extinction-based therapies as well as preventive agents in PTSD (Mueller and Cahill, 2010; Debiec et al., 2011; but see Stein et al., 2007).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Sophie Bordson for her excellent technical assistance.

These studies were supported by NIMH 5R01MH074697 to VR and UL RR031980, HL58120 to MZ and the Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ali SS, Young JW, Wallace CK, Gresack J, Jeste DV, Geyer MA, Dugan LL, Risbrough VB. Initial evidence linking synaptic superoxide production with poor short-term memory in aged mice. Brain Res. 2011;1368:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsene KM, Rajbhandari AK, Ramaker MJ, Bakshi VP. Discrete forebrain neuronal networks supporting noradrenergic regulation of sensorimotor gating. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(5):1003–1014. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong DM, Ross CA, Pickel VM, Joh TH, Reis DJ. Distribution of dopamine-, noradrenaline-, and adrenaline-containing cell bodies in the rat medulla oblongata: demonstrated by the immunocytochemical localization of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes. J Comp Neurol. 1982;212(2):173–187. doi: 10.1002/cne.902120207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asan E. Comparative single and double immunolabelling with antisera against catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes: criteria for the identification of dopaminergic, noradrenergic and adrenergic structures in selected rat brain areas. Histochemistry. 1993;99(6):427–442. doi: 10.1007/BF00274095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bao X, Lu CM, Liu F, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Zhu BQ, Foster E, Chen J, Karliner JS, Ross J, Jr, Simpson PC, Ziegler MG. Epinephrine is required for normal cardiovascular responses to stress in the phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase knockout mouse. Circulation. 2007;116(9):1024–1031. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrell J, de Kloet ER, Versteeg DHG, Bohus B. Inhibitory avoidance deficit following short-term adrenalectomy in the rat: the role of adrenal catecholamines. Behav. Neural Biol. 1983;39:241–258. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(83)90910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahill L, Alkire MT. Epinephrine enhancement of human memory consolidation: interaction with arousal at encoding. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;79(2):194–198. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(02)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cahill L, Pham CA, Setlow B. Impaired memory consolidation in rats produced with beta-adrenergic blockade. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;74(3):259–266. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cahill L, Prins B, Weber M, McGaugh JL. Beta-adrenergic activation and memory for emotional events. Nature. 1994;371:702–704. doi: 10.1038/371702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cedarbaum JM, Aghajanian GK. Noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus: inhibition by epinephrine and activation by the alpha-antagonist piperoxane. Brain Res. 1976;112(2):413–419. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark RE, Zola SM, Squire LR. Impaired recognition memory in rats after damage to the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20(23):8853–8860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08853.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clayton EC, Williams CL. Noradrenergic receptor blockade of the NTS attenuates the mnemonic effects of epinephrine in an appetitive light–dark discrimination learning task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2000;74:135–145. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M. Neurochemical modulation of sensory-motor reactivity: acoustic and tactile startle reflexes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1980;4(2):241–263. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(80)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis M, Redmond DE, Jr, Baraban JM. Noradrenergic agonists and antagonists: effects on conditioned fear as measured by the potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;65(2):111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00433036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dębiec J, Bush DE, LeDoux JE. Noradrenergic enhancement of reconsolidation in the amygdala impairs extinction of conditioned fear in rats--a possible mechanism for the persistence of traumatic memories in PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(3):186–193. doi: 10.1002/da.20803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Quervain DJ, Aerni A, Roozendaal B. Preventive effect of beta-adrenoceptor blockade on glucocorticoid-induced memory retrieval deficits. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):967–969. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dornelles A, de Lima MN, Grazziotin M, Presti-Torres J, Garcia VA, Scalco FS, Roesler R, Schröder N. Adrenergic enhancement of consolidation of object recognition memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;88(1):137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dulawa SC, Grandy DK, Low MJ, Paulus MP, Geyer MA. Dopamine D4 receptor-knock-out mice exhibit reduced exploration of novel stimuli. J Neurosci. 1999;19(21):9550–9556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engberg G, Elam M, Svensson TH. Effect of adrenaline synthesis inhibition on brain noradrenaline neurons in locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1981;223(1):49–58. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fendt M, Koch M, Schnitzler HU. Amygdaloid noradrenaline is involved in the sensitization of the acoustic startle response in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48(2):307–314. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferry B, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Role of norepinephrine in mediating stress hormone regulation of long-term memory storage: a critical involvement of the amygdala. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1140–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaspar P, Berger B, Febvret A, Vigny A, Henry JP. Catecholamine innervation of the human cerebral cortex as revealed by comparative immunohistochemistry of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. J Comp Neurol. 1989;279(2):249–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.902790208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geracioti TD, Baker DG, Kasckow JW, Strawn JR, Jeffrey Mulchahey J, Dashevsky BA, Horn PS, Ekhator NN. Effects of trauma-related audiovisual stimulation on cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine and corticotropin-releasing hormone concentrations in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(4):416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gold PE, van Buskirk RB. Facilitation of time-dependent memory processes with posttrial epinephrine injections. Behav Biol. 1975;13:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(75)91784-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold PE, van Buskirk R .Effects of alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists on post-trial epinephrine modulation of memory: relationship to post-training brain norepinephrine concentrations. Behav Biol. 1978;24(2):168–184. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(78)93045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gresack JE, Risbrough VB, Scott CN, Coste S, Stenzel-Poore M, Geyer MA, Powell SB. Isolation rearing-induced deficits in contextual fear learning do not require CRF(2) receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2010;209(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gresack JE, Risbrough VB. Corticotropin-releasing factor and noradrenergic signalling exert reciprocal control over startle reactivity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(9):1179–1194. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grillon C, Cordova J, Morgan CA, Charney DS, Davis M. Effects of the beta-blocker propranolol on cued and contextual fear conditioning in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175(3):342–352. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1819-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hokfelt T, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Johansson O. Immunohistochemical evidence for the existence of adrenaline neurons in the rat brain. Brain Res. 1974;66(2):235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holdefer RN, Jensen RA. The effects of peripheral D-amphetamine, 4-OH amphetamine, and epinephrine on maintained discharge in the locus coeruleus with reference to the modulation of learning and memory by these substances. Brain Res. 1987;417(1):108–117. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Introini-Collison I, Saghafi D, Novack GD, McGaugh JL. Memory-enhancing effects of post-training dipivefrin and epinephrine: involvement of peripheral and central adrenergic receptors. Brain Res. 1992;572(1–2):81–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90454-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Izquierdo LA, Barros DM, Medina I, Izquierdo JH. Stress hormones enhance retrieval of fear conditioning acquired either one day or many months before. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:203–213. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izquierdo I, Medina JH, Vianna MR, Izquierdo LA, Barros DM. Separate mechanisms for short- and long-term memory. Behav Brain Res. 1999;103(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janitzky K, Linke R, Yilmazer-Hanke DM, Grecksch G, Schwegler H. Disrupted visceral feedback reduces locomotor activity and influences background contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice. Behav Brain Res. 2007;182(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji JZ, Wang XM, Li BM. Deficit in long-term contextual fear memory induced by blockade of beta-adrenoceptors in hippocampal CA1 region. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17(9):1947–1952. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jurado-Berbel P, Costa-Miserachs D, Torras-Garcia M, Coll-Andreu M, Portell-Cortés I. Standard object recognition memory and "what" and "where" components: Improvement by post-training epinephrine in highly habituated rats. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehne JH, Davis M. Central noradrenergic involvement in yohimbine excitation of acoustic startle: effects of DSP4 and 6-OHDA. Brain Res. 1985;330(1):31–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King SO, Williams CL. Novelty-induced arousal enhances memory for cued classical fear conditioning: interactions between peripheral adrenergic and brainstem glutamatergic systems. Learn Mem. 2009;16(10):625–634. doi: 10.1101/lm.1513109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitchigina V, Vankov A, Harley C, Sara SJ. Novelty-elicited, noradrenaline-dependent enhancement of excitability in the dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9(1):41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korol DL, Gold PE. Epinephrine converts long-term potentiation from transient to durable form in awake rats. Hippocampus. 2008;18(1):81–91. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumari V, Cotter P, Corr PJ, Gray JA, Checkley SA. Effect of clonidine on the human acoustic startle reflex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;123(4):353–360. doi: 10.1007/BF02246646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leaton RN, Cassella JV. The effects of clonidine, prazosin, and propranolol on short-term and long-term habituation of the acoustic startle response in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20(6):935–942. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lew JY, Matsumoto Y, Pearson J, Goldstein M, Hökfelt T, Fuxe K. Localization and characterization of phenylethanolamine N-methyl transferase in the brain of various mammalian species. Brain Res. 1977;119(1):199–210. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang KC, Juler RG, McGaugh JL. Modulating effects of posttraining epinephrine on memory: involvement of the amygdala noradrenergic system. Brain Res. 1986;368(1):125–133. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maren S. Pavlovian fear conditioning as a behavioral assay for hippocampus and amygdala function: cautions and caveats. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(8):1661–1666. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarty R, Gold PE. Plasma catecholamines: Effects of footshock level and hormonal modulators of memory storage. Horm Behav. 1981;15(2):168–182. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(81)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGaugh JL. The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGaugh JL, Roozendaal B. Role of adrenal stress hormones in forming lasting memories in the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12(2):205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McIntyre CK, Hatfield T, McGaugh JL. Amygdala norepinephrine levels after training predict inhibitory avoidance retention performance in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(7):1223–1226. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McIntyre CK, McGaugh JL, Williams CL. Interacting brain systems modulate memory consolidation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.001. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McIntyre CK, Roozendaal B. Adrenal Stress Hormones and Enhanced Memory for Emotionally Arousing Experiences. In: Bermúdez-Rattoni F, editor. Neural Plasticity and Memory: From Genes to Brain Imaging. Chapter 13. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyashita T, Williams CL. Peripheral arousal-related hormones modulate norepinephrine release in the hippocampus via influences on brainstem nuclei. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan CA, 3rd, Grillon C, Southwick SM, Davis M, Charney DS. Fear-potentiated startle in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(6):378–385. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00321-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgan CA, Southwick SM, Grillon C, Davis M, Krystal JH, Charney DS. Yohimbine-facilitated acoustic startle reflex in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110(3):342–346. doi: 10.1007/BF02251291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller D, Cahill SP. Noradrenergic modulation of extinction learning and exposure therapy. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murchison CF, Zhang XY, Zhang WP, Ouyang M, Lee A, Thomas SA. A distinct role for norepinephrine in memory retrieval. Cell. 2004;117(1):131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielson KA, Jensen RA. Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist antihypertensive medications impair arousal-induced modulation of working memory in elderly humans. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;62:190–200. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nordby T, Torras-Garcia M, Portell-Cortes I, Costa-Miserachs D. Posttraining epinephrine treatment reduces the need for extensive training. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Donnell T, Hegadoren KM, Coupland NC. Noradrenergic mechanisms in the pathophysiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50(4):273–283. doi: 10.1159/000080952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okuda S, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid effects on object recognition memory require training-associated emotional arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(3):853–858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307803100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106(2):274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quevedo J, Sant'Anna MK, Madruga M, Lovato I, de-Paris F, Kapczinski F, Izquierdo I, Cahill L. Differential effects of emotional arousal in short- and long-term memory in healthy adults. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;79(2):132–135. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(02)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quirarte GL, Galvez R, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Norepinephrine release in the amygdala in response to footshock and opioid peptidergic drugs. Brain Res. 1998;808:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quirarte GL, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory storage involves noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(25):14048–14053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risbrough VB, Geyer MA, Hauger RL, Coste S, Stenzel-Poore M, Wurst W, Holsboer F. CRF1 and CRF2 receptors are required for potentiated startle to contextual but not discrete cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(6):1494–1503. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roder S, Ciriello J. Innervation of the amygdaloid complex by catecholaminergic cell groups of the ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332(1):105–122. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roozendaal B, Okuda S, Van der Zee EA, McGaugh JL. Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory requires arousal-induced noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(17):6741–6746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601874103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roozendaal B, Sapolsky RM, McGaugh JL. Basolateral amygdala lesions block the disruptive effects of long-term adrenalectomy on spatial memory. Neuroscience. 1998;84(2):453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosario LA, Abercrombie ED. Individual differences in behavioral reactivity: correlation with stress-induced norepinephrine efflux in the hippocampus of Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48(6):595–602. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sallinen J, Haapalinna A, Viitamaa T, Kobilka BK, Scheinin M. Adrenergic alpha2C-receptors modulate the acoustic startle reflex, prepulse inhibition, and aggression in mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18(8):3035–3042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-03035.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Samson Y, Wu JJ, Friedman AH, Davis JN. Catecholaminergic innervation of the hippocampus in the cynomolgus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1990;298(2):250–263. doi: 10.1002/cne.902980209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwabe L, Römer S, Richter S, Dockendorf S, Bilak B, Schächinger H. Stress effects on declarative memory retrieval are blocked by a beta-adrenoceptor antagonist in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(3):446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spanswick SC, Sutherland RJ. Object/context-specific memory deficits associated with loss of hippocampal granule cells after adrenalectomy in rats. Learn Mem. 2010;17(5):241–245. doi: 10.1101/lm.1746710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stein MB, Kerridge C, Dimsdale JE, Hoyt DB. Pharmacotherapy to prevent PTSD: Results from a randomized controlled proof-of-concept trial in physically injured patients. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):923–932. doi: 10.1002/jts.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sternberg DB, Korol D, Novack GD, McGaugh JL. Epinephrine-induced memory facilitation: attenuation by adrenoceptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;129(1–2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ. Hippocampus, amygdala, and memory deficits in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1990;37(1):57–79. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Swanson LW, Hartman BK. The central adrenergic system. An immunofluorescence study of the location of cell bodies and their efferent connections in the rat utilizing dopamine-B-hydroxylase as a marker. J Comp Neurol. 1975;163(4):467–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Torras-Garcia M, Portell-Cortés I, Costa-Miserachs D, Morgado-Bernal I. Long-term memory modulation by posttraining epinephrine in rats: differential effects depending on the basic learning capacity. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(2):301–308. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valentinuzzi VS, Kolker DE, Vitaterna MH, Shimomura K, Whiteley A, Low-Zeddies S, Turek FW, Ferrari EA, Paylor R, Takahashi JS. Automated measurement of mouse freezing behavior and its use for quantitative trait locus analysis of contextual fear conditioning in (BALB/cJ × C57BL/6J)F2 mice. Learn Mem. 1998;5(4–5):391–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White DA, Birkle DL. The differential effects of prenatal stress in rats on the acoustic startle reflex under baseline conditions and in response to anxiogenic drugs. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;154(2):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s002130000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams CL, McGaugh JL. Reversible lesions of the nucleus of the solitary tract attenuate the memory-modulating effects of posttraining epinephrine. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107(6):955–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams CL, Men D, Clayton EC, Gold PE. Norepinephrine release in the amygdala after systemic injection of epinephrine or escapable footshock: contribution of the nucleus of the solitary tract. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112(6):1414–1422. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Young JW, Wallace CK, Geyer MA, Risbrough VB. Age-associated improvements in cross-modal prepulse inhibition in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124(1):133–140. doi: 10.1037/a0018462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang WP, Guzowski JF, Thomas SA. Mapping neuronal activation and the influence of adrenergic signaling during contextual memory retrieval. Learn Mem. 2005;12(3):239–247. doi: 10.1101/lm.90005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]