Abstract

Introduction

This paper reports my experience as a teacher of clinical ultrasound (US) in an African hospital. While US in tropical countries has received some attention and a few papers – though possibly fewer than deserved by this issue-are available in the medical literature on this subject, very little has been done in terms of assessment of teaching.

Materials and methods

Given the increasing number of groups, NGOs and volunteers that go to Africa and other resource limited settings to do this, I thought that sharing my experience with those who have walked or are thinking of walking the same path could be mutually beneficial.

Results

The first section of the article presents the situation where I've been working in the past 13 years, the second section details our teaching programme.

Discussion

This report describes the rationale for the implementation of ultrasound training programmes in rural areas of Africa and lessons learnt with 13 years experience from the UK with recommendations for the way forward.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Training, Tropical medicine, Developing countries, Africa

Sommario

Introduzione

Questo articolo presenta la mia esperienza di insegnamento dell'ecografia clinica in un ospedale africano. L'uso dell'ecografia nei paesi tropicali è menzionato da alcuni articoli – meno di quanto l'argomento meriterebbe – nella letteratura medica, ma poco o nulla è stato detto sulla valutazione dell'addestramento ecografico in questo contesto.

Materiali e metodi

Dato il sempre maggior numero di gruppi, organizzazioni non governative, volontari e altro che si recano in Africa a insegnare l'ecografia, ho pensato di presentare la mia esperienza a coloro che hanno fatto o intendono fare la stessa cosa, in modo da aprire una discussione.

Risultati

La prima parte dell'articolo presenta la situazione in cui ho lavorato negli ultimi 10 anni, la seconda parte presenta il programma in modo dettagliato.

Discussione

Viene anche descritta la giustificazione logica dell'istituzione di programmi di addestramento ecografico in zone rurali Africane e lezioni apprese in 10 anni di esperienza nel Regno Unito con le indicazioni su come procedere in futuro.

Introduction

Medical ultrasound in developing countries

Ultrasound (US) is an important, established diagnostic test in developed countries. Its use has been recommended for developing countries by specialists with a long-standing experience in tropical medicine such as Palmer [1], Mets [2] Hoyer&Weber [3] and Mindel [4].

The literature clearly indicates that ultrasound improves case management for a wide diversity of clinical presentations: “the enhanced diagnostic accuracy, certainty and promptness is especially valuable for healthcare settings in which the probability of correcting a clinically misclassified case is reduced due to scarcity of physicians and limited availability of complimentary diagnostic tests” [5].

US has been recommended for developing countries by the World Health Organization since it is a technique that provides images and information immediately, is relatively inexpensive, portable and non-invasive whilst relatively safe [6].

US can prevent unnecessary surgery and allow more conservative management where appropriate, as the equivalent of laying open the abdomen without the need for surgical intervention.

Conversely, US is a very operator dependant technique [7] and training to a level of competence is essential, as to the inadequately trained or the inexperienced ultrasound is equally suited to misinterpretation [8].

Furthermore, health services, especially in rural and remote areas of developing countries are insufficient and lacking but this is even more so when it comes to diagnostic imaging [9].

Uganda

Uganda lies between the Eastern and Western branches of the Great Rift Valley in Eastern Africa and is similar in size to the UK.

In 2002 Uganda was found to have a population of approximately 24.6 million, 87% of whom live in rural areas. The annual national population growth rate is estimated at 3.5%. Kampala, the capital and only city in Uganda is home to 1.2 million people.

Since Museveni took power in 1986 Uganda's economy has maintained a growth rate of 5–6% per annum. The economy is based for the most part on agriculture, accounting for 60% of the GDP, making it extremely vulnerable to fluctuations in commodity prices. Over 90% of the populations are subsistence farmers and 80% of these are women who grow crops mainly for their own consumption. Major export crops include coffee, fish, tea and tobacco.

The richest 10% of people earn 15 times more than the poorest 10%. As a result 44% of people live below the national poverty line.

Low national income goes some way to explaining Uganda's lack of development. 31% of adults are illiterate and 48% of the population lack sustainable access to a safe water supply [10].

Basic health indicators are also very poor. Life expectancy is only 45.7 years and over 14% of children die before their fifth birthday. There has been some success in reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS in recent years; nevertheless 4.1% of the population is HIV positive. Poor basic health indicators are exacerbated by low spending on healthcare and only 5 doctors for every 100,000 people. This compares to 164 doctors per 100,000 people in the UK [11].

Since independence in 1962 Uganda's development and prosperity has been significantly undermined by civil and international war. Whilst armed conflict continues between government and Lords Resistance Army forces in the North of the country however, the majority of the country has enjoyed relative peace and stability over the past 15 years.

Methods

Kumi hospital – background

Kumi hospital was founded in 1929 as a leprosy colony and is located in the Teso region of Eastern Uganda close to the main road between Mbale and Soroti.

Between 1986 and 1992 the Teso region, whose main economic activity was cattle trading, was devastated by both civil war and cattle rustling conducted by a hostile neighbouring nomadic tribe. The hospital was also affected; having its water supply destroyed.

In 1997 the hospital transformed to a general hospital, with a capacity of 290 beds and specialising in the care of people with disabilities.

A large number of patients are also seen each day in the outpatient clinic.

The hospital operates as a Private Not for Profit Hospital (PNFP). It receives funding from a number of donors and the Ugandan Government. Patients are also required to make a small contribution towards the cost of some consultations, investigations and treatment. However, due to the support of the donors, the hospital is able to offer a number of free services to the local community (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Photo of a young patient at Kumi.

Due to its relative proximity to the continuing armed resistance in the North of Uganda, the Teso region continues to receive a large number of refugees, known as internally displaced persons (IDP's) from the conflict. In addition to their need for shelter, food and water these people also need access to health services and this places an extra strain on the hospital.

The greatest challenge facing the hospital is the absence of a piped water supply. Currently all water for the hospital and staff housing is extracted from boreholes and wells.

The electricity supply in Uganda is extremely unreliable, resulting in frequent power cuts and periods of low voltage supply.

As with most hospitals in Uganda, due to the extremely high patient to nurse ratio, basic nursing care of the patients in the hospital has to be carried out by relatives of the patient (generally referred to as the guardians). This releases the small number of nurses available for tasks such as changing dressings, dispensing drugs, keeping records and coordinating investigations and procedures. Since Kumi may be many miles from the patient's village and transport is scarce and costly, guardians normally stay with the patient at the hospital. Unfortunately there is no accommodation specifically for the use of guardians so most sleep alongside the patient's bed on the ward or out in the open. (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mother with inpatient and sibling.

To complicate matters further patients in countries such as Uganda often present late at the hospital and the reasons for this are numerous, among which are poverty, inadequate and unaffordable transport, hospital charges, mistrust of hospitals and faith in traditional healers.

Health links

Currently within the U.K. more than 70 large teaching hospitals or healthcare providers are involved in Health Links, defined as:

-

1)

Alliance between institutions of the North and South to achieve a mutually desired goal of becoming centres of excellence.

-

2)

A long-term partnership between a UK Hospital and a counterpart institution overseas, which can have a unique role in healthcare development.

Health Links are committed to building permanent capacity and make sustainable change through sharing skills and knowledge.

The primary aim of health links is to address the needs of the recipient institute but it is well recognized there are definite benefits for all parties involved, as the volunteers who participate develop themselves both professionally and personally (www.optin.uk.net).

Implementation of a medical ultrasound training program in Uganda

Over the past thirteen years I have been involved in ultrasound training in Africa, mostly in rural settings; much of this work initially was sponsored and overseen by BMUS (British Medical Ultrasound Society). As a guide for resources required we implemented two ultrasound services and trained on average four practitioners to a level of competence at each institute, Kamuli Hospital, central Uganda and Kumi Hospital in the far East of Uganda for approximately 12, 000 pounds which currently equates to 14,330 Euros. Each project has taken around three years with volunteers visiting 2–3 times each year, basic costs included flights, visas, anti-malarials equating to around 700 pounds (currently 836 Euros) per volunteer per single visit. Volunteers generally travelled in pairs but this is particularly important if an individual has not visited Africa or a developing country before. It was important to deliver some pre departure training and risk assessment in order to allow visits to be carried out more safely and with less risk to health.

The purpose of the ultrasound training programmes is to enable select local personnel to acquire the necessary skills to perform, interpret, evaluate and report ultrasound examinations; to manage an ultrasound service and enhance the planned management for appropriate patients.

Some of the initial ultrasound training programmes were sponsored by the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS); the second hand ultrasound equipment had already been donated by the ultrasound manufacturers, serviced and transported to the two rural African sites, one to each. Teaching volunteers from the U.K. were selected from a variety of disciplines within the British Medical Ultrasound Society, including Radiologists, Sonographers and Ultrasound Lecturers.

A detailed syllabus was designed for the curricular taught content of the programme (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Ultrasound lecture in Uganda.

Training visits

Training visits were planned to occur three times per year with two teaching volunteers travelling on each occasion and spending 3 weeks delivering the programme. On each occasion the volunteers would write a detailed report of their visit with regard to objectives achieved, student assessment and usage of the ultrasound service within the hospital-feedback would then be given to the next group of volunteers. It is important to monitor the delivery of such a programme and to include methods of evaluation, particularly from the students and staff in Uganda, the recipients.

Good communication from both the donor and recipient is paramount for such a project to be successful. Also of critical importance is for all of the recipient hospital staff to be aware of the project and its aims.

Clinical staff need to be aware of the availability of the ultrasound service and most importantly referrals need to be appropriate, nursing staff assist with appropriate preparation of the patients, administrative staff control charges for such a service and appropriate management of this is critical.

An additional diagnostic test is a valuable source of income for a healthcare provider but there will always be “running costs” and these must be budgeted for and appropriate supplies available such as coupling gel, non-spermicidal condoms.

In countries such as Uganda, patients attend the hospital on a need basis, out-patient clinics are held 5 days per week usually without any formal appointment system in place so taught delivery was organized to compliment this, formal lectures delivered in the morning whilst patients are referred and practical scanning sessions throughout the rest of the day. Teaching volunteers and students are encouraged to attend any multi-disciplinary team meetings or audit meetings that occur within the hospital in order to maximize the potential for implementation of an ultrasound service and to encourage awareness and further knowledge of all staff.

Assessment of competence

At the end at the end of each teaching visit students were assessed with a written theory assessment and some form of clinical assessment with the results and feedback given to the students prior to departure. At the end of the training course, which on average ran over a 2–3 year period, students were given a certificate of attendance issued by BMUS. This is given when students prove basic competencies in ultrasound practice both at a clinical and academic level. It is critical to identify one of the successful students who are then capable and willing to ensure that further skills are transferred locally beyond the lifetime of the training programme (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Ultrasound training in Uganda.

Directed study

In addition a form of directed study was also employed, such as preparation of a 2000 word case study or an oral presentation of a specific finding for the next pair of teaching volunteers; the plan was to publish some of these cases for the British audience so we could share the useful knowledge of our Ugandan students.

Students also kept a log of interesting cases with a library of images and documentation of the specific clinical question, ultrasound findings, final diagnosis and outcome.

Feedback

Feedback from students in Uganda during delivery read “The students have had a lot of clinical lectures and resources to enable them to continue building on this knowledge between visits and would like more clinical sessions with questions/answers, rather than a large number of lectures.

They would like to have further sessions on liver, splenic and renal pathology, particularly related to tropical diseases, malaria, TB and HIV.”

This allowed for appropriate preparation for the next group of teaching volunteers who needed to be appropriately knowledgable of ultrasound in Tropical Medicine and in my opinion this is our weakness as this is highly specialized and exposure by the teaching volunteers is limited prior to involvement-this is an area for consideration and development.

Outcome of audit

The outcome of audit at all sites is supported by the literature and demonstrates that ultrasound positively affects management in two thirds of cases [5]. This is particularly valuable where there are limited resources allowing prioritisation of those cases that require operative management and a more conservative approach, where infection and mortality rates are high post operatively this can only be a positive.

A financial audit carried out in 2004/5 found the income generated by the hospital as a result of the ultrasound service was £4225 approximately 5000 euros.

Long term linkage

Once the training programme is complete it is essential to maintain long term linkage with the institute or hospital in order to fully evaluate the training programme;

Attempts at this have included sponsorship for attendance at the Annual Scientific Meeting in the UK for one of the Ugandan students, donation of the BMUS scientific journal every quarter to each institute.

Maintenance of the ultrasound service

Selection and Maintenance of the ultrasound equipment has to be a primary concern at all sites prior to implementation a sturdy, portable and basic piece of ultrasound equipment has been the most successful option for our programmes. With kind agreement from the manufacturers who donated the equipment at that time it was possible to ship between countries for servicing and replacement parts when required. Ultrasound equipment is more readily available in Uganda now than ever before and as for all nations less expensive.

Education for teaching volunteers

One primary benefit for the UK volunteers who participate is enhancement of their ultrasound knowledge by encountering a greater variety of disease processes and pathologies with varied clinical presentations and ultrasound appearances.

Results

Variety of pathologies and disease processes encountered

Abdomen

AIDS has a wide variety of clinical manifestations and ultrasound is ideally suited to aid the planned management of this condition [12] particularly in rural areas of developing countries such as Uganda where the diagnostic tests available are limited [6,13–15].

Burkitts lymphoma

Burkitt's lymphoma is the commonest childhood cancer in Africa, with a peak incidence between 4 and 9 yrs and a male predominance.

It is associated with frequent exposure to EBV before the age of 1 year and was recognized in 1911 by Denis P. Burkitt, an English surgeon working in Africa.

It occurs as a complication of AIDS, often presents with tumours of the jaw and GI involvement. US is useful to monitor regression (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Ultrasound image of renal lesions typical of Burkitt's lymphoma.

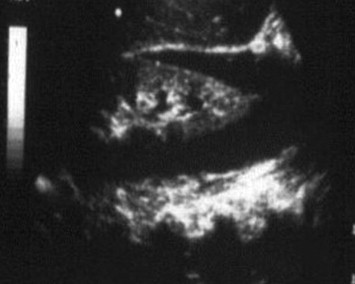

Page kidney-sub capsular haematoma

Cervical lymphadenopathy in the tropics is commonly due to tuberculosis or lymphoma; this 45-year-old lady presented with splenomegaly and obvious cervical lymphadenopathy. On ultrasound the spleen was markedly enlarged but no obvious focal lesions were identified. Incidental findings included a large right renal sub-capsular haematoma but there was no history of trauma. Recommended clinical observations would include monitoring blood pressure and renal function as a Page Kidney may develop.

Page kidney is caused by the accumulation of blood in the perinephric or subcapsular space, resulting in compression of the involved kidney, renal ischemia, and high renin hypertension [16] (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Ultrasound image right renal sub-capsular haematoma – page kidney.

Schistosomiasis may be responsible for hydroureter and hydronephrosis or pyoureter and pyonephrosis in its final stages. The wall of the bladder also thickens irregularly and there may be bright echoes from patches of calcification.

Other causes of renal abnormalities in the tropics include: Hydatid disease, filariasis (causing chyluria), tuberculosis, Burkitt's lymphoma, haemoglobinopathy (sickle cell disease).

Gynaecology

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is a most serious complication of sexually transmitted diseases and is extremely common in the tropics. The long-term sequelae include infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and disabling pelvic pain (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Pelvic inflammatory disease not diseases.

Molar pregnancy is very common in many third world countries with the risk of development of choricarcinoma, and is usually associated with pelvic infection. The tumour often progresses rapidly in young women, who may also have chronic pelvic inflammatory disease; fluid filled uterine cavity was present beyond a stenosed cervical canal (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Renal metastases in a patient with choriocarcinoma.

Discussion

Benefits for volunteers involved

According to recent research by Demos 2001 some of the higher order skills that are acquired and enhanced as a result of exposure to working in developing countries include global awareness, adaptability, interpersonal skills, handling responsibility, stress management, self-assurance, problem solving, exchanging skills, strategic thinking, clinical education and a sense of humour [17] Other authors have identified the benefits of increased cultural awareness on return from Overseas work to employment in the NHS [18].

The attraction comes in one example of a small notice in a busy outpatient clinic of one 300 bedded hospital in rural Uganda where the queues are endless “We seldom think of what we have but always of what we lack, this tendency has caused more misery than all the diseases in life.” Kumi Hospital March 2002.

Recommendations for the future

In the past, poor governance and war have severely limited Africa's growth and development but after years of stagnation, Africa has now been growing solidly for several years, Rwanda is currently enjoying economic growth twice that of Europe and the United States. There are signs of turnaround in Africa and lots to be optimistic about. One way of developing the capacity of local health institutions in developing countries is through the provision of agreed training projects, in areas such as medical ultrasound, that match agreed identified needs. Perhaps it is time for national and international collaboration of the respective professional bodies and organisations to co-ordinate much of the Overseas activity that occurs with regard to medical ultrasound and the provision of appropriate training, funding and sustainability of such work so that the limited resources available to assist our colleagues Overseas is used to maximum effect. This is most effective when the ministries of Health and leaders are aware and involved in activity and decision making and it should always match the Health action plan or Millennium Development Goals for that country.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

Grateful acknowledgement from the author to Maria Teresa Giordani, MD, Italy.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Palmer P. Diagnostic imaging for developing countries. WHO Chron. 1985;39:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mets T. Clinical ultrasound in developing countries. Lancet. 1991:337–358. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90981-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyer P., Weber M. Ultrasound in developing world. Lancet. 1997:350–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mindel S. Role of imager in developing world. Lancet. 1997;350:426–429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bussmann H., Koen E., Arhin-Tenkorang D., Munyadzwe G., Troeger J. Feasibility of an ultrasound service on district health care level in Botswana. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:1023–1031. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Future use of new imaging technologies in developing countries. Report of a WHO scientific group. In: World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. Geneva, 1985. [PubMed]

- 7.Kurjak A., Breyer B. The use of ultrasound in developing countries. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1986;12:611–621. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Training in diagnostic ultrasound: essentials, principles and standards. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1998; 875. [PubMed]

- 9.Ostensen H. Developing countries. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;26(Suppl. 1):S159–S161. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briggs P. Bradt; 2003. Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legget I. Oxfam Publishing; 2001. Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunetti E., Brigada R., Poletti F., Maiocchi L., Garlaschelli A.L., Gulizia R. The current role of abdominal ultrasound in the clinical management of patients with AIDS. Ultraschall Med. 2006;27:20–33. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tshibwabwa E.T., Mwaba P., Bogle-Taylor J., Zumla A. Four-year study of abdominal ultrasound in 900 Central African adults with AIDS referred for diagnostic imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:290–296. doi: 10.1007/s002610000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinkala E., Gray S., Zulu I., Mudenda V., Zimba L., Vermund S.H. Clinical and ultrasonographic features of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV positive adults in Zambia. BMC Infect Dis. 2009:9–44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller T, Goblirsch S, Wallrauch C, Lessells R, Brunetti E. Abdominal tuberculosis: sonographic diagnosis and treatment response in HIV-positive adults in rural South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.McCune T.R., Stone W.J., Breyer J.A. Page kidney: case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1991;18:593–599. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banatvala N., Macklow-Smith A. Bringing it back to blighty. BMJ. 1997:314–322. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson K.J. Working in other countries. Work opportunities in developing countries broaden the mind. BMJ. 2000:320–1543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.