Abstract

Until 20 or 30 years ago, the diagnosis and treatment of breast disease was managed exclusively by the surgeon. This situation has changed to some extent as a result of recent technological advances, and clinicians’ contributions to the diagnostic work-up and/or treatment of these cases can begin at any time. If they are the first physician to see the patient after the examination and formulation of a diagnostic hypothesis, they will almost always have to order a panel of imaging/instrumental examinations that is appropriate for the type of lesion suspected, the patient’s age, and other factors; if they intervene at the end of the diagnostic work-up, it will be their job to arrive at a conclusion based on all of the data collected. The clinical examination includes various steps – history taking and inspection and palpation of the breasts – each of which is essential and requires the use of appropriate methods and techniques. The diagnostic capacity of the examination will depend largely on the consistency of the breasts, but it is influenced even more strongly by the doctor–patient relationship. Physicians must know their patient well, listen to and understand what she is saying, explain their own findings and verify that the explanations have been understood, and they must be convincing. Clinicians must also be able to assess the results of imaging studies (rather than relying solely on the radiologist’s report), and this requires interaction with other specialists. The days are over when a clinician or radiologist or sonographer worked alone, certain that his/her examination method was sufficient in itself: today, teamwork is essential. But this also means that each member of the team must be extremely competent in his/her own sector and be aware of the other team members’ limitations and expectations. The clinical examination remains central to the process since it is the basis for selecting appropriate treatment.

Sommario

Da quando si conosce la patologia mammaria la diagnosi e la terapia di tale patologia sono state a totale appannaggio del chirurgo, situazione che è proseguita fino a qualche decennio fa. Il recente progresso tecnologico ha modificato, in parte, questa situazione e il clinico può entrare nel percorso diagnostico o terapeutico in qualsiasi momento. Se è il primo coinvolto, dopo l’esame e dopo un’ipotesi diagnostica, dovrà, quasi sempre, orientarsi verso indagini strumentali in relazione al sospetto, all’età della paziente ecc., se è l’ultimo anello deve arrivare a una conclusione mettendo insieme tutte le informazioni. L’esame clinico è composto di varie fasi: anamnesi, ispezione, palpazione, ognuna essenziale. Ogni singola fase va affrontata con metodo e tecnica appropriata. La capacità diagnostica dell’esame clinico è influenzata dalla costituzione della mammella, ma ancor di più è condizionata da uno stretto rapporto tra paziente e medico che deve conoscere molto la paziente che gli sta davanti e che non solo deve “visitare”, ma capire, spiegare, accertarsi che si abbia capito, convincere. È inoltre indispensabile che il clinico sia in grado di esaminare le indagini strumentali e non limitarsi a leggere i referti, quindi interagire con gli altri specialisti. L’epoca del clinico o del radiologo o dell’ecografista che lavora da solo credendo che il proprio esame sia sufficiente o sganciato da altri contesti è finita da tempo, tutti hanno bisogno di tutti. È però vero che ciascuno deve essere estremamente competente nel suo settore e deve conoscere i limiti e le aspettative di chi collabora in altre specialità, come rimane valida la regola che la clinica resta comunque il momento centrale, non fosse altro perché poi deve affrontare la terapia.

Keywords: Breast disease, Clinical examination, Clinical features of breast lesions

Introduction

Breast disease was first described in the Smith Papyrus, which dates back to 3000 BC. In 1882, Halsted standardized the mastectomy, the surgical procedure that bears his name, and it represented the treatment of choice for breast cancer until the late 1950s. From the beginning, the diagnosis and treatment of breast lesions were managed exclusively by the surgeon, and this was the rule until 20 or 30 years ago.

It is important to recall that mammography was developed in 1913. It was already being used in the 1950s, and by the 1970s it was widely employed in the United States. It arrived at the University of Milan Medical Center at the end of the 1980s.

Sonography followed a similar trend: It was introduced in 1953 by Wild and Reid, and the first World Congress of Ultrasonography was held in Vienna in 1969. The Giornale Italiano di Ultrasonologia was founded some 20 years later in 1990. In his well-known 1975 textbook, Diseases of the Breast [1], however, Haagensen dedicated 36 full pages to the clinical examination. The supplementary examinations cited included transillumination (1 page), mammography (4 pages), and xerography, thermography, and isotope studies (a few lines each), but there was no mention at all of sonography. In other words, until the final decades of the 20th century, diagnosis of breast disease remained primarily a responsibility of the surgeon.

The picture has changed markedly since then: thanks to major technological advances, our ability to detect and identify lesions within the breast has reached remarkable levels. The breast lesions we are looking for today are may be only a few millimeters in diameter, and in this setting technology has replaced clinical acumen. One wonders what role the clinician – in particular the surgeon – plays in current management of breast disease.

The picture that is emerging is one in which tiny subclinical lesions are being found thanks to clinical or screening mammography and subsequently characterized via sonography [2] and/or stereotactic techniques, which allow them to be removed when necessary. This phase is followed by treatment with targeted radiation therapy, radiofrequency ablation, or other methods, and completed with suitable drug therapy.

One might conclude that the surgeon has no place in this picture, that the clinician contributes little or nothing during the diagnostic phase. But the situation is actually far more complex.

First of all, screening programs do exist, but their geographical coverage is far from complete, and they naturally focus on only certain age groups. Screening rates in Italy reach a maximum of 85% in the Lombardy region, but the national average is only 64%. In the second place, even in regions where screening is active and there is a high level of healthcare teaching, there are still numerous cases of advanced breast cancers. In the author’s personal experience in screening programs at the ICP and later at the Fondazione Ospedale Maggiore of Milan (Tables 1 and 2), 16.7% of the tumors detected were >2 cm in diameter, 55.8% were more than 1 cm, and 1% were classified T4. Screening programs are highly conducive to early diagnosis, so in general clinical practice even higher percentages of tumors will be found after the initial stage. It is also important to recall that some tumors are manifested primarily or exclusively by clinical signs.

Table 1.

Temporal variation in the size of breast carcinomas at the time of diagnosis (author’s personal case series).

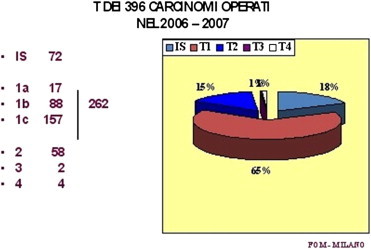

Table 2.

Size distribution of breast cancers operated on at Milan’s FondazioneOspedale Maggiore in 2006–2007 (author’s personal case series).

Therefore, the role of the surgical clinician is still fundamental: indeed, the surgeon is the focal point around which all other specialists revolve, although his/her role is clearly less important – or rather markedly different – than it was in the past.

For the sonographer, it is important to recall how clinicians approach the diagnosis of breast lesions and what they expect from diagnostic imaging procedures.

Clinical features of breast lesions

Haagensen, already cited above, is known for his comment, “If we were one day forced to give up all diagnostic methods except one, the clinical examination would certainly be the one we would keep”. The clinical examination has always been considered the simplest method, the easiest to perform, the least expensive, and above all the most reliable. And this view is in large part correct. The physical examination can be carried out anywhere: the only instruments required are the eyes, the hands, the ability to converse with the patient, and the intellect.

But this is not the entire story. The physical examination is neither simple nor quick. It is absolutely operator-dependent and therefore requires a high level of experience. It cannot be standardized, and it is strongly influenced by a number of factors (generally speaking, the size and structure of the breasts and the size of the lesions).

Finding a nodule less than 1 cm in diameter and formulating a hypothesis on its probable nature is extremely difficult in breasts that are small and fatty and virtually impossible in those that are large and firm. The sensitivity and specificity of the examination depend on the possibility of identifying the lesion, and the skill of the examiner is at least as important as that of the radiologist or sonographer. If the lesion can be objectively demonstrated, the specificity is high; in expert hands it can exceed 85% [3].

If we exclude screening programs, where the diagnosis necessarily depends on a single examination, it makes little sense to compare the sensitivities of the various diagnostic methods to identify the best one. The real question to ask is to what extent each method contributes to the formulation of a correct diagnosis. From this point of view, the clinical examination is an undeniably valid, even irreplaceable component of the diagnostic work-up, not only because it increases the diagnostic accuracy of other approaches (especially mammography and sonography) by at least 10%. Its main virtue is that it can guide and help organize subsequent phases of the work-up, identifying additional studies that may be needed to clarify the picture or to resolve doubts arising from discordant findings generated by previous studies. Furthermore, the physical examination is sometimes the only method for detecting breast disease (e.g., Paget’s carcinoma [4] or lesions in the extreme periphery of the organ, which are difficult to visualize with mammography).

Clinical breast examinations can be carried out in all settings, and they are apparently easy to perform. Nonetheless, it is important to recall what we are looking for and what conditions will optimize the chances of success. The diagnostic capacity of the examination is influenced by the consistency of the breast [5]: difficulties increase with the density of the tissue. Consequently, the best time to examine the breasts of a reproductive-aged woman is during the immediate postmenstrual period.

The examination requires a well-lighted room, an examination table, and above all time. The old clinicians claimed that a reliable breast examination took at least 30 min. Today’s examinations are more rapid, in part because the results will be supplemented by other studies. But it is important to recall that the success of the breast examination depends largely on the physicians’ relationship with the patient. Physicians need to know something about the person they are examining. They need to be able to understand what she is saying, to explain what they have found, to verify that their words have been understood and that they are convincing.

The basic technique is that used for any clinical examination: history taking and a physical examination consisting of inspection and palpation (Fig. 1). The patient history is often viewed mainly as a pretense for “breaking the ice,” but it is actually a fundamental part of the breast work-up. Information on family history, menarche, parity, age at first pregnancy, use and duration of breast-feeding, current menstrual status, age at menopause, use of hormones or other types of therapy – all can be important in diagnosing breast disease and accurately determining the patient’s level of risk. The history will also reveal why the patient has sought medical care, her attitude toward preventive measures, her tendency to under- or overestimate the importance of symptoms, and if the examination discloses the presence of disease, the history will provide clues to the patient’s ability to understand the situation and deal with it, her expectations, and how she is likely to react.

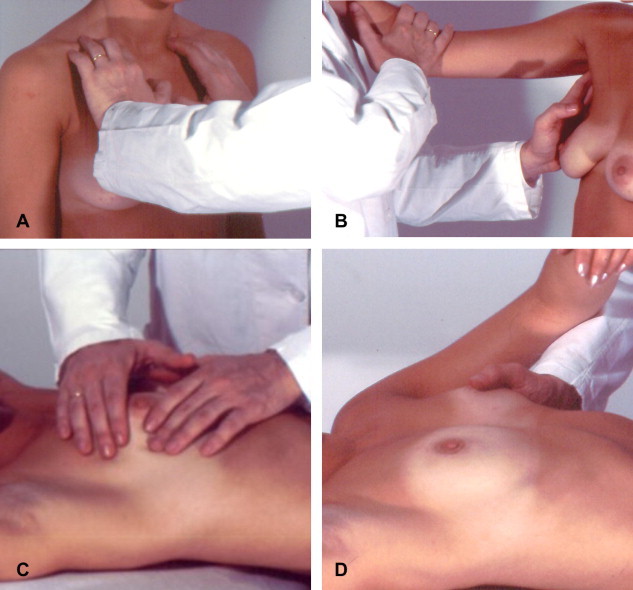

Fig. 1.

Clinical examination of the breast includes several phases. The exam begins with the patient in the supine position. The nipple is inspected and palpated (C and D). The patient is then placed in the upright position for examination of the supraclavicular fossa (A) and then the axilla (B).

The examiner must also carefully review the results of all previous examinations, particularly mammograms. This entails direct visualization of the images, not simply reading the original examiner’s report. All examiners, including radiologists and sonographers, should take a careful patient history, if possible with the aid of a predefined form that includes a section to be filled in by the patient herself.

Discovering exactly why the patient has requested an examination and the characteristics/localization of any symptoms she is experiencing can accelerate and orient the diagnostic process. The first question that needs to be asked routinely is why the patient has come in for an examination. There are fundamentally two responses: the first is breast-cancer prevention, and the second is that she has been experiencing symptoms – pain, a palpable lump (or nodule), nipple discharge, changes in the shape of the breast and/or in the overlying skin. The frequency is highly variable depending on the geographical location of the examining center, the cultural characteristics of the population, and the degree of healthcare education. In the absence of programs aimed at prevention, reports of pain, nodules, and/or nipple secretion are more common [6]. The importance of these symptoms can be summarized by an analysis of the clinical presentations of carcinoma, as shown by the various statistics (Table 1).

Once the history has been taken, the physical examination begins with inspection and palpation of the breasts (Fig. 1). The importance of visual inspection should not be under-rated: it can orient the examiner toward a correct diagnosis, and it often reveals significant features that escape detection by imaging studies, including skin changes (Figs. 2 and 3), deformities (Fig. 2), small depressions or erosive lesions (Fig. 3) [7]. The major focal points of the inspection are the areola and nipple (Fig. 1D).

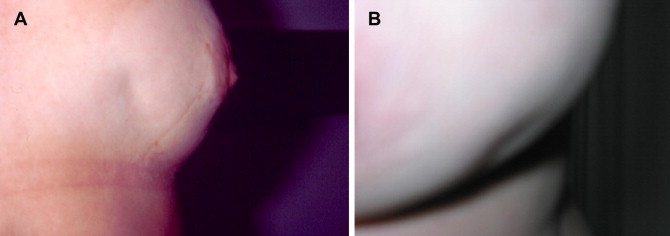

Fig. 2.

Clinical examination of the breast can reveal cutaneous retraction (A) and/or depressions (B), which are important signs of neoplastic disease.

Fig. 3.

Clinical examination of the breast. The presence of cutaneous ulceration is an important finding that indicates advanced disease.

The history and visual inspection are undeniably important, but the central component of the clinical examination is breast palpation (Fig. 1). All regions of the breast, the supraclavicular area (Fig. 1A), and the axilla (Fig. 1B) should be carefully palpated with a technique that has been carefully mastered. The patient should be examined in both the supine and upright positions. This approach allows full control of the region and facilitates characterization of the mobility of any nodules and the presence of cutaneous fixation. Special attention is reserved for nodules: their number, location, and characteristics, including size, consistency, margins, surfaces, mobility with respect to the rest of the breast tissue and surrounding tissues (skin, chest wall), pain (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Distribution of breast carcinomas by clinical presentation based on literature data and analysis the author’s personal experience.

| Nodule | 61.7% |

| Nodule and/or retraction | 28.3% |

| Nodule and secretion | 3.6% |

| Dimpling | 2.4% |

| Nipple changes | 2.0% |

| Bloody secretion | 1.6% |

| Axillary lymphadenopathy | 0.4% |

Table 4.

Breast nodule analysis. Clinical diagnostic form used in the 1970s.

| Volume changes | |

| Reduction | −1 |

| No change | 0 |

| Increase | +1 |

| Consistency | |

| Soft | −1 |

| Intermediate | 0 |

| Firm | +1 |

| Shape | |

| Roundish | −1 |

| Poorly defined | 0 |

| Irregular | +1 |

| Surface | |

| Smooth | −1 |

| Granular | 0 |

| Irregular | +1 |

| Borders | |

| Well-defined, regular | −1 |

| Undefined | 0 |

| Irregular or infiltrating | +1 |

| Intramammary mobility | |

| Clear-cut | −1 |

| Modest | 0 |

| Scarse-absent | +1 |

| Protrusion | |

| Unappreciable | −1 |

| Palpable | 0 |

| Visible | +1 |

| Tenderness | |

| Present | −1 |

| Slight | 0 |

| None | +1 |

| Nipple discharge | |

| Non-serohematic | −1 |

| None | 0 |

| Serohematic | +1 |

| Axillary lymphadenopathy | |

| Little or none | −1 |

| Present | +1 |

| Skin | |

| Smooth, mobile | −1 |

| Dimpled or fixed | +1 |

| Algebraic sum | Diagnostic significance |

| ≤−2 | Benign |

| −1 to +1 | Uncertain |

| ≥+2 | Malignant |

In addition to nodules, two other frequent symptoms are likely to alarm most patients: nipple discharge and pain. Compression of the breast frequently elicits some type of nipple secretion. In many cases, this finding has no pathological significance. This is particularly true when the secretion is bilateral, involves multiple pores, and is provoked by compression. In these cases, it may be useful to check the patient’s prolactin levels to exclude the presence of hypophyseal disease. Spontaneous discharge from a single pore is more worrisome, particularly if the secretions are abundant and/or hematic or serohematic. In these cases, careful study of the ductal system is warranted, and a smear of the discharge should be examined cytologically. These findings are frequently observed in patients with intraductal papillary tumors, some of which are carcinomas [8]. In a non-negligible percentage of cases, confirmation of the diagnosis requires resection of the duct or ducts involved [9]. As for breast pain or tenderness, it can have several causes. They may be related to the menstrual cycle, inflammatory factors, or extramammary causes. Pain is rarely the first and sole sign of malignancy [10].

At the end of the clinical examination, the examiner must formulate a diagnostic hypothesis and make plans for further studies and possible treatment.

It is now widely agreed that senology is a multispecialist field. The concept of a single specialist who deals with all breast problems has now been definitively abandoned, and the same goes for the clinical-ultrasound examination strategy that was in vogue about a decade ago [5,11]. Today, we are much more oriented toward the concept of a Senology Unit, where various specialists with specific training in breast disease work together in a coordinated fashion. Surgeons, radiologists, and sonographers who dedicate all or most of their time to senology plan their schedules to include group discussions of complex cases and second-level diagnostic studies.

The clinician, who is often the one who will be responsible for treating the patient, is automatically designated to collect all of the diagnostic data, review the various findings, and reach a conclusion regarding the diagnosis. Rigid diagnostic protocols are neither feasible nor useful. Clinicians can intervene at any time in the work-up. If they are the first physician to see the patient after the examination and formulation of a diagnostic hypothesis, they will almost always have to select an appropriate panel of imaging/instrumental examinations in light of the type of lesion suspected, the age of the patient, and other factors; if they are involved at the end of the diagnostic work-up, it will be their job to arrive at a conclusion based on all of the data collected and direct visualization of the diagnostic images obtained (not just the examiners’ reports). Sonographers should take particular care to provide the clinician with images that are significant.

At the end of the diagnostic process, there should be no discordant data: everything should be correspondent or integrated. Imaging study data should confirm the presence of the clinical symptom and add more precise information on lesion size, number, location, and relation to surrounding structures. As far as ultrasonography is concerned, clinicians expect to receive confirmation that what they found is also seen by the sonographer and/or additional information that further clarifies the picture. Certainty is often impossible, but something more is needed. A typical situation is one in which the imaging data reveal a subclinical lesion. In cases like these, one sees how important the Senology Unit really is. If the imaging study or clinical examination has been performed by a member of the unit’s staff, rapid discussion by the different specialists on the team is often enough. If instead the examination has been done elsewhere, difficulties may arise, and the examination may have to be repeated, delaying diagnosis and increasing costs. The time frames are those typical of situations in which data from different sources – sometimes incomplete or discordant – have to be comparatively analyzed and second-level diagnostic procedures planned and carried out (e.g., imaging-guided biopsies for cytology or histology, examinations to locate nonpalpable lesions).

Apart from diagnostic information, clinicians expect radiologists and sonographers to provide them with information that can be used to plan appropriate treatment. For this reason, it is important that diagnostic imaging specialists are also informed on the therapeutic options that are available and aware of the therapeutic relevance of the information they provide. There are essentially two questions that require answers: is surgery needed and if so what type?

An analysis of the possible answers to these questions would require more space than is available here, but we have attempted to summarize the various treatment options and their indications in Table 5 (which has all the advantages and disadvantages of this type of presentation).

Table 5.

Measures indicated by the results of each type of examination.

| Examination type | Additional diagnostic tests | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical examination results | ||

| CL1 | <40 years. Ultrasound (US) | Follow-up |

| 40–55 years. US + mammography | ||

| >55 years. Mammography (+US if the breast is dense) | ||

| CL2 | <40 years. US | Follow-up (unless there is conflicting data from another study or other reasons for suspicion, e.g., lesion size, recent finding, patient age) |

| 40–55 years. US + mammography | ||

| >55 years. Mammography (+US if the breast is dense) | ||

| CL3 | US + mammography | Core biopsy + re-evaluation |

| CL4 | US + mammography | Cytology/core biopsy + surgery |

| CL5 | US + mammography | Cytology + surgery (or oncology consult) |

| Ultrasound findings | ||

| U1 | >40 years. Mammography + CL | Follow-up |

| U2 | Mammography + CL | Follow-up and possibly cytology |

| U3 | Mammography + CL | Core biopsy/VABB + re-evaluation |

| U4 | Mammography + CL | Core biopsy/VABB + surgery |

| U5 | Mammography + CL | Citologico/core biopsy + surgery |

| Mammographic findings | ||

| R1 | <55 years. US + CL | Follow-up |

| R2 | US + CL | Follow-up |

| R3 | US + CL | VABB + re-evaluation |

| R4 | US + CL | VABB/removal with or without localization |

| R5 | US + CL | Removal with or without localization |

CL1, U1, R1 = No lesion; CL2, U2, R2 = Benign lesion; CL3, U3, R3 = Probably benign; CL4, U4, R4 = Probably malignant; CL5, U5, R5 = Malignant.

In general, it is important to recall that treatment choices are influenced by the degree of uncertainty, and the degree of uncertainty is the highest one in the three examinations.

One can also try to summarize the types of surgery that can be performed. It is important to stress, however, that one cannot adhere to rigid protocols in this phase: decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis.

Generally speaking, unless they are frankly malignant, palpable lesions can be removed with lumpectomy; those that are not palpable should be managed with localization and tumorectomy (with or without prior biopsy for microhistological analysis). The same approach is used for suspicious lesions, although the lesion should be subjected to intraoperative frozen section analysis unless it is less than 1 cm in diameter. If the lesion is clearly malignant, the primary treatment options are well standardized (Table 6).

Table 6.

Current options for primary breast cancer surgery.

| T <3 cm N0 | Breast-conserving surgery + sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) + local radiotherapy (RT) | – Also used for multifocal disease in the same quadrant |

| Not multifocal | ||

| T <3 cm N1–N2 | Breast-conserving surgery + axillary lymphadenectomy + RT | – Also used for multifocal disease in the same quadrant |

| T >3 cm in pt. with macromastia | ||

|

|

|

| T4 | Various options to be selected with the oncologist | – The lesion is surgically removed whenever possible |

| Tis | Complete surgical removal (possibly with RT) |

|

Conclusions

The days are over when a clinician or radiologist or sonographer worked alone, certain that his/her examination method was sufficient in itself for diagnosing breast lesions: today teamwork is essential. But this means that each member of the team must be extremely competent in his/her own sector and be aware of the other team members’ limitations and expectations. As we have seen, the results of a given diagnostic study cannot be interpreted outside the larger context, which includes the findings of other specialists working as an integrated team. This is the only way to achieve high diagnostic accuracy. No one is the sole protagonist in this process, but all members must be constantly aware of the importance of their individual contributions and work consistently to the highest of their ability.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Appendix. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Haagensen C.D. WB Saunders Company; 1975. Diseases of the breast. Pagg. 115 e seg. Ed. It. Demi. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahbar G., Sie A.C., Hansen G.C., Prince J.S., Melany M.L., Reynolds H.E. Benign versus malignant solid breast masses: US differentiation. Radiology. 1999;213:889–904. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc20889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veronesi U. Masson; Milano: 1999. Senologia oncologica. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meibodi N.T., Ghoyunlu V.M., Javidi Z., Nahidi Y. Clinicopathologic evaluation of mammary Paget’s disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:21–23. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.39736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Felice C., Savelli S., Angeletti M., Ballesio M., Manganaro L., Meggiorini M.L. Diagnostic utility of combined ultrasonography and mammography in the evaluation of women with mammographically dense breasts. J Ultrasound. 2007;10:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberl M.M., Phillips R.L., Lamberts H., Okkes I., Mahoney M.C. Characterizing breast symptoms in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:528–533. doi: 10.1370/afm.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veronesi U., Coopmans De Yoldi G.F. Medico Scientifiche; Pavia: 1997. Senologia diagnostica per immagini. p. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han B.K., Choe Y.H., Ko Y.H., Yang J.H., Nam S.J. Benign papillary lesions of the breast: sonographic-pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18:217–223. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards T., Hunt A., Courtney S., Umeh H. Nipple discharge: a sign of breast cancer? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:124–126. doi: 10.1308/003588407X155491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cartier J.M., Bourjat P. Verduci editore; 2000. Imaging del seno. p. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dambrosio F., Amy D. C.I.C. Edizioni internazionali; 1994. Atlante clinico di Ecografia mammaria. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.