Abstract

Vascular anomalies are classified as vascular tumors and vascular malformations. Venous vascular malformations are the most common type of vascular malformation. They may be isolated or multiple and they rarely affect the trunk. The authors report a rare case of isolated venous vascular malformation of the abdominal wall with an emphasis on the related MRI and ultrasound (US) features.

Keywords: Venous vascular malformations, Abdominal wall, Ultrasound

Sommario

Le anomalie vascolari sono comunemente classificate in tumori di origine vascolare e malformazioni vascolari. Le malformazioni venose vascolari sono il tipo più comune di malformazioni vascolari.

Esse possono presentarsi come isolate o multiple e raramente interessano il tronco. In questo articolo è riportato un caso di malformazione venosa vascolare isolata della parete addominale, le sue caratteristiche alla Risonanza Magnetica (RM) e all’ecografia.

Introduction

Venous vascular malformation (VVM) is the most common type of vascular malformation (VM). It is classified as low-flow VM based on the angiographic features (Table 1) [1,2]. VVMs consist of thin-walled, dilated, sponge-like vessels with normal endothelial lining and deficient smooth muscle tissue. They are bluish in color and often asymptomatic. VVMs usually occur in the skin and subcutaneous tissues, but in some cases they involve the muscle and viscera [1]. They are usually diagnosed and characterized by means of US and MRI, the latter being the most useful tool for documenting the nature and extent of the disease [1–4]. Indications for treatment are: pain, appearance and functional problems. Therapeutic approaches are sclerotherapy and, in selected cases, surgical resection [1–3]. The authors report a case of VVM involving the abdominal wall with an emphasis on the related magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US) features.

Table 1.

VM classification.

| Vascular malformations |

|---|

| Low-flow |

| Simple |

| – Capillary (Port wine stain) |

| – Venous |

| – Lymphatic |

| High-flow |

| Simple (rare) |

| – Arterial |

| Mixed (common) |

| – Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) |

| – Capillary-arterial-venous |

| Mixed |

Case report

A 34-year-old male, a mechanic and a smoker, was referred to our department for evaluation of a “recurrent superficial angiodysplasia”. The patient had undergone surgical resection of the lesion twice, 12 and 10 years before. Consistent with the natural history of VM, the lesion recurred after resection and grew as the patient got older.

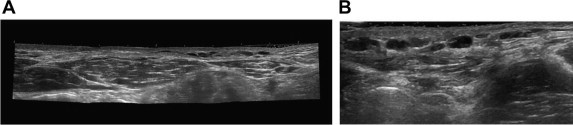

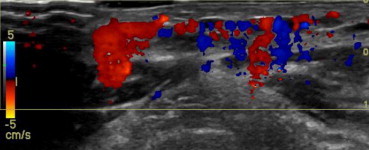

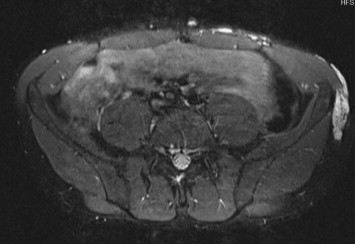

Clinical examination revealed a soft, bluish, compressible lesion in the lower left quadrant of the abdominal wall. US demonstrated dilated channels involving subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 1). Color Doppler revealed low flow within the vessels (Fig. 2). MRI showed infiltrating non-mass-like lesions involving both superficial and deep tissues. The lesion extended from the skin through the subcutaneous tissues infiltrating the rectus abdominis muscle. It showed high signal intensity on T-2 weighted and short-tau inversion recovery(STIR) images (Fig. 3). After intravenous administration of contrast enhancement, there was a delayed (100 s) contrast filling of the vessels. The patient was scheduled for sclerotherapy of the lesion.

Figure 1.

Abdominal wall VVM. US reveals dilated vessels in the subcutaneous tissues: (A) panoramic view; (B) phleboliths can be seen inside vessels.

Figure 2.

Abdominal wall VVM. Color Doppler US confirms the vascular nature of the lesion.

Figure 3.

Abdominal wall VVM. STIR sequences provide a better definition of the spatial relationship in vascular lesions (hyperintense) involving the superficial and deep tissues, spreading from the skin to the rectus abdominis muscle.

Consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Discussion

Vascular anomalies are classified as vascular tumors and VMs [5]. The prevalence of VM is 1.2%–1.5%. VMs can be associated with other disorders such as the Parkes-Weber or Sturge-Weber syndrome [4].

Nowadays, a VM is classified as a high-flow or low-flow (LF) VM (LFVM) on the basis of flow dynamics, with LFVM accounting for more than 90% of lesions outside the central nervous system (CNS). VMs are LFVMs composed of abnormally formed, dilated venous channels that can be sub-classified into four groups according to their anatomic features: Type I, isolated malformation without peripheral drainage; Type II, VM that drains into normal veins; Type III, VM that drains into dysplastic veins; Type IV, venous ectasia. VVMs can be isolated or multiple and they involve mainly the neck (40%), extremities (40%), and rarely the trunk (20%) [5]. VVMs are usually noted at birth, and they become more prominent as the child grows. They present as blue masses that are easily compressed by exerting gentle pressure. In case of large lesions complications can occur such as phlebolith formation and localized intravascular coagulopathy [4].

US is the initial diagnostic tool for evaluating VM [6], as US can delineate the extent of superficial lesions. US has proved to be a useful tool for distinguishing VM from hemangioma and VVM from capillary VM or arteriovenous malformation (AVM) [6]. MRI is the most useful imaging tool for defining the superficial extent of the lesion and the involvement of subcutaneous tissue. MRI demonstrates lobulated and septated masses or channels using low signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted or STIR images. These findings correlate to the presence of single or multiple venous lakes containing stagnant blood. STIR sequence or similarly T2-weighted imaging with fat suppression have been found to be the most sensitive and specific methods for detection of the extent and the depth of the lesion, due to the bright signal of the lesion on a low-signal background (muscle, fat, bone) [4].

The use of contrast enhancement permits a correct definition of the lesion as high-flow or low-flow VM and evaluation of the connection to the vascular system. Contrast enhanced MRI (CEMRI) typically shows gradual and delayed contrast filling and absence of arteriovenous shunting. Ohgiya et al. measured the time interval between the onset of enhancement and maximum percentage of enhancement in the lesion, the so-called “contrast rise time” (CRT). They showed that LFVM presented a mean contrast rise time of 88 s. A CRT threshold of 30 s was set, guaranteeing 100% specificity and sensitivity in the differentiation of low-flow from high-flow VMs [2,7].

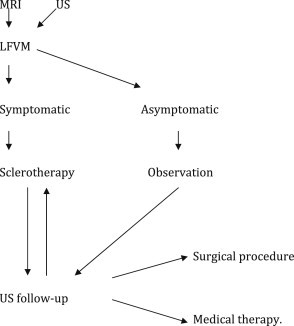

Sclerotherapy is the mainstay of treatment; it is based on the injection of an agent (commonly absolute ethanol) to induce an inflammatory reaction and obliteration of the affected veins. Selected cases should undergo surgical resection later [2] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Algorithm for the management of VVM.

VVM were previously called angiomas, cavernous angiomas and phlebangiomas. This confusing terminology continues to result in improper diagnosis and treatment of these lesions [1]. In the case reported above, the natural history of the lesion as well as the clinical and imaging characteristics: slow but continuous expansion of the lesion without spontaneous regression, recurrence after surgical treatment and low-flow contrast enhancement dynamics are all typical features of VVM [1–4,8].

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article

References

- 1.Marler J.J., Mulliken J.B. Current management of hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Clin Plast Surg. 2005 Jan;32(1):99–116. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyodoh H., Hori M., Akiba H., Tamakawa M., Hyodoh K., Hareyama M. Peripheral vascular malformations: imaging, treatment approaches, and therapeutic issues. Radiographics. 2005 Oct;25(suppl. 1):S159–S171. doi: 10.1148/rg.25si055509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puig S., Casati B., Staudenherz A., Paya K. Vascular low-flow malformations in children: current concepts for classification, diagnosis and therapy. Eur J Radiol. 2005 Jan;53(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flors L., Leiva-Salinas C., Maged I.M., Norton P.T., Matsumoto A.H., Angle J.F. MR Imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations: diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up. Radiographics. 2011 Sep-Oct;31(5):1321–1340. doi: 10.1148/rg.315105213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernemann U., Kramer U., Miller S., Bisdas S., Rebmann H., Breuninger H. Current concepts in the classification, diagnosis and treatment of vascular anomalies. Eur J Radiol. 2010 Jul;75(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paltiel H.J., Burrows P.E., Kozakewich H.P., Zurakowski D., Mulliken J.B. Soft-tissue vascular anomalies: utility of US for diagnosis. Radiology. 2000 Mar;214(3):747–754. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.3.r00mr21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohgiya Y., Hashimoto T., Gokan T., Watanabe S., Kuroda M., Hirose M. Dynamic MRI for distinguishing high-flow from low-flow peripheral vascular malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Nov;185(5):1131–1137. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarantino C.C., Vercelli A., Canepari E. Angioma of the chest wall: a report of 2 cases. J Ultrasound. 2011 Mar;14(1):18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.