Abstract

Introduction

Assessment of US ability to identify subcutaneous nodular lesions using conventional B mode imaging (CBMI) and tissue second harmonic imaging (THI).

Materials and Methods

Three different types of equipment were used (Philips Envisor HDC, Philips HD 11 XE and GE Logic E) with 12–13 MHz probes and THI probes with variable frequency. One experienced operator studied 31 patients (24 women, 7 men, mean age 49 ± 15) with 52 subcutaneous nodular lesions of which 43 were palpable and 9 were nonpalpable. Statistical analysis was carried out using chi-square test.

Results

19/52 subcutaneous nodular lesions were hyperechoic, 10/52 were isoechoic and 23/52 were hypoechoic. Of the hyperechoic nodules, 8/19 (42%) (p < 0.005) were not detected using THI, as they “disappeared” when THI was activated. Of the isoechoic nodules only 1/10 was not detected using THI, and of the hypoechoic nodules only 2/23 were not detected. Of the nodular lesions detected using CBMI and also using THI (41/52), 16/41 were shown more clearly using THI than using BMCI. No nodule was detected with the exclusive use of THI.

Conclusions

The statistical significance of the “disappearing” lesions (p < 0.005), mainly hyperechoic (42%), at the activation of THI must lead to a reconsideration of routine activation of THI during the entire US examination in the evaluation of subcutaneous lesions in order to avoid the risk of missing important lesions. The present results suggest that both BMCI and THI should be used in the study of subcutaneous lesions.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Harmonic imaging, Contrast resolution, Subcutaneous tumors

Sommario

Introduzione

È stata indagata la capacità di identificare con l’ecografia lesioni nodulari del sottocute sia con l’utilizzo dell’imaging convenzionale B mode (BMCI) che con la Tissutal Harmonic Imaging (THI).

Materiali e Metodi

Sono state utilizzate tre apparecchiature (Philips Envisor HDC, Philips HD 11 XE, e GE Logic E) con sonde da 12–13 MHz e THI a frequenza variabile. Da unico operatore esperto sono stati studiati 31 pazienti (24F, 7 M, età 49 ± 15) con 52 lesioni nodulari del sottocute di cui 43 palpatoriamente evidenti e 9 non evidenti. È stato utilizzato il test del Chi Quadro per l’analisi statistica.

Risultati

19/52 lesioni nodulari del sottocute hanno presentato ecostruttura iperecogena, 10/52 isoecogena e 23/52 ipoecogena. Dei noduli iperecogeni, 8/19 (p < 0.005), 42%, non sono stati evidenziati con il THI, di fatto ‘scomparendo’ all’attivazione dell’armonica tissutale; degli isoecogeni solo uno non è stato individuato con il THI, e degli ipoecogeni solo 2/23. Delle lesioni nodulari evidenti anche con il THI (41/52) 16/41 erano evidenziate con maggiore nitidezza con l’utilizzo del THI vs BMCI (p < 0.002). Nessuna lesione nodulare è stata scoperta con l’utilizzo esclusivo della THI.

Conclusioni

La significatività statistica della ‘scomparsa’ delle lesioni (p < 0.005) soprattutto iperecogene (il 42%) con l’utilizzo della seconda armonica (THI) porta a riconsiderare l’utilizzazione di un preset con THI inserito per tutta la durata dell’esame nella valutazione delle focalità del sottocute, per non incorrere nel rischio di non visualizzare tali lesioni. Riteniamo quindi opportuno di considerare sempre l’utilizzo di entrambe le metodiche, sia della BMCI che del THI nello studio del sottocute.

Introduction

Tissue Second Harmonic Imaging (THI) has an established role in diagnostic ultrasound (US) examinations as widely reported in the literature [1–4]. THI is an excellent tool for improving contrast resolution and lateral resolution [5–10] of anatomic regions, both superficial tissues and deep-lying organs. With the improvement of transducer technology, and particularly the development of multi-frequency transducers, tissue characterization using THI has become part of the routine of US examinations. This means that THI is automatically activated in many presets for the study of various organs and structures so that it is active during the entire US examination.

The THI technique uses return resonant frequency, which is typical of the tissues, received by the transducer within the frequency range of US and perceived by the crystals of the US probe. In conventional B mode imaging (CBMI) the US beam is transmitted at a given frequency, but it is received as a series of echoes composed of a multitude of other frequencies of less intensity, which are distributed around the fundamental frequency (F0) of a group of harmonics (frequencies which degrade the quality and the resolution of the image) and also of a series of higher-frequency harmonics equal to double, triple, four times the fundamental frequency of which one in particular, the second, is properly filtered and separated from the others and will generate the so-called THI image; other higher-frequency harmonics [11] are not detectable because of the elevated absorption.

Therefore, the return rate of the transmitted US beams presents many peaks of which the first is the fundamental resonant frequency (f0) of high intensity, and the second, producing twice the f0 frequency of a lesser intensity, will present properties that are derived from the characteristics of the insonated tissue. Using a band-pass filter and, in the newest equipment, a digital encoding of the US beams [12], the scanner will isolate only the second harmonic image eliminating many of the artifacts that degrade image quality such as side lobe artifacts, which are the backscatter from the lower frequencies of the US beam elements [12] thus eliminating spurious frequency signals and finally zeroing artifacts due to multiple reflections, all unable to generate harmonics.

The aim of this study was to investigate possible image quality degradation when this method of image filtration, THI, was activated during the investigation of lesions located in the superficial tissue layers. The study evaluated the ability of the method to identify subcutaneous nodular lesions using CBMI, i.e. fundamental frequency including disturbing secondary frequencies, and THI which filters the US signals in order to acquire only the second harmonic component.

Materials and methods

Three different types of equipment were used (Philips Envisor HDC, Philips HD 11 XE, and GE Logic E) all provided with broad-band multi-frequency linear probes of 12–13 MHz and a return frequency THI probe of 10 MHz (Philips) and 12 MHz (GE).

All US investigations were performed by the same experienced operator. Thirty-one patients were studied (24 women, 7 men; mean age 49 ± 15); they had in total 52 nodular lesions in the subcutaneous tissue of which 43 were palpable and 9 were not detectable by physical examination alone. Four patients had multiple lesions. Once the nodular lesions were identified using CBMI, maximum diameter was measured and echogenicity was evaluated and compared to that of the subcutaneous tissues. Subsequently the lesions were re-evaluated using THI. Ten patients underwent US study using all 3 types of US equipment.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to assess statistical significance of the obtained data. The data were reported as mean values ± SD and as percentages. All tests were performed using statistical software for biomedical research, Version 6 for Windows, McGraw-Hill, by Stanton A. Glantz.

Results

All nodular lesions were located in the subcutaneous tissues. The lesions were mainly located in the limbs (35/52) with a prevalence of the upper limbs (27/35); 17/52 lesions were located on the torso (10 on the back and 7 on the chest/abdomen). All nodular areas presented an oval shape and prevalent horizontal axis suggestive of subcutaneous lipomas or fibromas. Some of them (32/52) presented a slightly inhomogeneous echotexture and only 10/52 presented a weak power Doppler signal. In total 19/52 (36.5%) of the subcutaneous nodular lesions were hyperechoic compared to the subcutaneous adipose tissue, 10/52 (19%) were isoechoic and 23/52 (44%) were hypoechoic.

The lesions presented an average diameter of 17.79 mm, SD ± 8.9 mm, median 17 mm, range 5–42 mm. Of the hyperechoic nodular lesions, 8/19 (p < 0.005) 42%, (mean diameter 14.5 ± 4.8 mm, range 8–21 mm) were not detected using THI as they “disappeared” when this device was activated (Figs. 1–4) resulting in a total loss of contrast resolution and spatial resolution (axial and lateral). Of the isoechoic lesions only 1/10 (Figs. 5 and 6) was not detected with THI (p > 0.05) and of the hypoechoic lesions only 2/23 (p > 0.05) were not clearly distinguishable from the surrounding subcutaneous tissue.

Fig. 1.

Hyperechoic subcutaneous nodular lesion visualized at conventional imaging (BMCI).

Fig. 2.

Same scan as Fig. 1 after activation of harmonic imaging (THI).

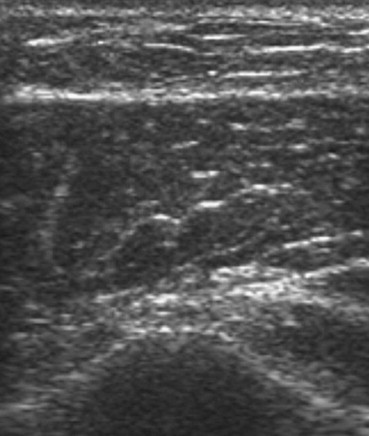

Fig. 3.

Iso-hyperechoic subcutaneous nodular lesion visualized at conventional imaging (BMCI).

Fig. 4.

Same scan as Fig. 3 after activation of harmonic imaging (THI).

Fig. 5.

Isoechoic subcutaneous nodular lesion visualized at conventional imaging (BMCI).

Fig. 6.

Same scan as Fig. 5 after activation of harmonic imaging (THI).

Of the nodular lesions which were detected using both techniques, CBMI and THI (41/52), 16/41 were depicted with greater sharpness and contrast using THI as compared to CBMI (p < 0.002), but in 10/41 (p < 0.005) the use of THI significantly degraded the image quality (a more or less pronounced reduction of contrast resolution) although identification was still possible maintaining the same spatial resolution. The remaining lesions detected using both techniques (15/41) presented no significant differences related to contrast against the surrounding tissues when THI was activated. In this study, no nodule was detected with the exclusive use of THI. In the 10 patients who underwent US examination using all 3 types of US equipment, the THI image was clear and presented no dissimilarities.

The results of this study do not establish how to predict, on the basis of the echostructure, which of the explored lesions could be missed and which could be more clearly depicted using THI. However, it seems that lesions with a slightly inhomogeneous echostructure at CBMI examination were more easily detected using THI, and despite losing spatial resolution and contrast resolution they were still detectable albeit with greater difficulty.

Discussion

As reported in numerous studies [1–10] THI can greatly improve contrast resolution, when broad-band high-frequency probes are used. THI considerably reduces the most frequent artifacts occurring in connection with CBMI [13,14] (the so-called side lobes, backscatter images due to lower frequencies of beams), and THI therefore clearly reduces reverberation artifacts, speckle artifacts and coherent wave interference, which can cause granular appearance of the homogeneous tissue thereby degrading the image contrast and resolution of anatomical details. Also clutter artifacts are reduced (i.e. background noise caused by spurious echoes which alter the normal homogeneous appearance of fluid collections). THI can therefore provide considerably increased contrast resolution [15–17].

Conversely, other studies have advised against using tissue coding, such as Van Wijk and Thijssen [18] who in a study on the performance of US equipment in 2002 reported a modest reduction in axial resolution compared to CBMI performance. Stavros [12] furthermore reported a poor definition of the deep lying anatomic structures and reduced axial resolution particularly if the equipment did not have digital encoding of the US beam (but this is not the case in the present study).

Summing up the data reported in the literature, there seems to be 3 main limitations to the use of THI: the first is related to the reduced ability to penetrate the tissues, i.e. the inability to depict deep lying anatomical structures; the second limitation is caused by the reduced frame rate (tolerable until color and power Doppler are used simultaneously), and the third, which Stavros considered as a minor limitation, i.e. the benefits of THI are mainly achieved in the mid-field, whereas the benefits are reduced when anatomical areas closer to the skin surface are studied.

To our knowledge, the scientific literature has so far not reported on the negative effects of activating THI as described in this paper. In some patients, activation of THI produced a varying degree of increased diffuse, homogeneous echogenicity of the subcutaneous tissues, which eliminated the echogenic difference between the nodular lesions and normal tissue. In contradiction with the data reported in the literature, THI activation led in some patients to a significant decrease in contrast resolution and particularly in spatial resolution. In a fairly high percentage of the present patient population the lesion actually “disappeared” from the image, when THI was activated, and in other patients the characteristics of the nodules were less clearly depicted so that it was not possible to distinctly identify the presence of neoplastic pathologies.

This phenomenon seemed to occur only in the tissue layers located up to 2 cm under the skin surface. In our experience this “disappearance” in connection with THI activation does not occur in more deeply located nodular areas, for example in the subfascial planes.

Our first hypothesis is that this phenomenon occurs in some patients because of particular characteristics of the subcutaneous tissue response to the THI activation and that it varies from patient to patient.

Conclusions

It is a well-known fact that modern, sophisticated US equipment has presets which can automatically activate THI during US investigation, particularly in the study of superficial tissues. THI has in fact greatly improved CBMI with its selective filtering of the return echoes thereby greatly reducing degradation of the imaging properties [19–21]. However, this study shows that the activation of THI can in some patients lead to the “disappearance” of important findings, particularly in the study of more superficial structures. The statistical significance of this “disappearance” of lesions (p < 0.005), mainly hyperechoic lesions (42%), which occurred when THI was activated, must lead to a reconsideration of the use of automatic THI activation during the entire US evaluation of focal skin lesions, as this involves a serious risk of missing nodular lesions which would be easily identified using CBMI.

In the light of these results it may be appropriate to use both techniques, CMBI and THI, in the study of subcutaneous tissues without favoring one technique at the expense of the other. Even though the present results show that CMBI is required and seems to be sufficient in the study of subcutaneous tissues, it should be underlined that there are still situations in which THI, thanks to subtraction and filtering of the image, may add further details and important information in the study of other types of lesions located in the subcutaneous tissues.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

SIUMB (School of Pisa for Basic and Specialist Ultrasound in Urgency and Emergency Evaluation) Award for the Best Poster at the National SIUMB Congress 2010.

AppendixSupplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Christopher T. Finite amplitude distortion-based inhomogeneous pulse echo ultrasonic imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1997;44:125–139. doi: 10.1109/58.585208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christopher T. Experimental investigation of finite amplitude distortion-based second harmonic pulse echo ultrasonic imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1998;45:158–162. doi: 10.1109/58.646920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li P.C., Shen C.C. Effects of transmit focusing on finite amplitude distortion based second harmonic generation. Ultrason Imaging. 1999;2:243–258. doi: 10.1177/016173469902100401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tranquart F., Grenier N., Eder V., Pourcelot L. Clinical use of ultrasound tissue harmonic imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1999;25:889–894. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie W.G.M. Axial resolution. Ultrasound Q. 1992;10:80–100. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar P.M., Dala Krishna P., Newhouse V.L. Advantages of subharmonic over second harmonic backscatter for contrast-to-tissue echo enhancement. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1998;14:213–233. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Averkiou MA, Roundhill DN, Powers JE. A new imaging technique based on the nonlinear properties of tissues. In: IEEE Proceedings of the Ultrasonics Symposium, vol. 2; 1997; p. 1561–1566.

- 8.Desser T.S., Jeffrey R.B. Tissue harmonic imaging techniques: physical principles and clinical applications. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2001;22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(01)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y.D., Zagzebski J.A. Computer model for harmonic ultrasound imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2000;47:1000–1013. doi: 10.1109/58.852084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward B., Baker A.C., Humphrey V.F. Nonlinear propagation applied to the improvement of resolution in diagnostic medical ultrasound. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:143–154. doi: 10.1121/1.417977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stramare R., Dorigo A., Velgos F., Rubaltelli L. Fisica degli ultrasuoni. In: Busilacchi P., Rapaccini G.L., editors. Ecografia Clinica. Idelson Gnocchi; Napoli: 2006. pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stavros A.T. Breast ultrasound equipment requirements. In: Stavros A.T., editor. Breast ultrasound. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2004. pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley N.J., Griffith K., Houldsworth G., Holloway M., Dunn M.A. A review of two alternative ultrasound quality assurance programmes. Eur J Ultrasound. 2001;12:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0929-8266(00)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thijssen J.M., Oosterveld B.J. Performance of echographic equipment and potentials for tissue characterization. In: Viergever M.A., Todd-Prokopek A., editors. Computer science in medical imaging. Springer; Berlin: 1988. pp. 455–468. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doratiotto S., Zuiani C., De Candia A., Bazzocchi M. Ecografia Compound Digitale. In: Busilacchi P., Rapaccini G.L., editors. Ecografia Clinica. Idelson Gnocchi; Napoli: 2006. pp. 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barella H.M. ATL and Philips medical systems. MedicaMundi. 1999;43(3):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burckhardt C. Speckle in ultrasound B-mode scans. IEEE Trans Son Ultrason. 1978;25:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Wijk M.C., Thijssen J.M. Performance testing of medical ultrasound equipment: fundamental vs. harmonic mode. Ultrasonics. 2002;40:585–591. doi: 10.1016/s0041-624x(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen C.C., Li P.C. Harmonic leakage and image quality degradation in tissue harmonic imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2001;48(3):728–736. doi: 10.1109/58.920701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen C.C., Hsieh Y.C. Optimal transmit phasing on tissue background suppression in contrast harmonic imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34:1820–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Browne J.E., Watson A.J., Hoskins P.R., Elliot A.T. Investigation of the effect of subcutaneous fat on image quality performance of 2D conventional imaging and tissue harmonic imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31(7):957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.