Abstract

Breast biopsy consists in the collection of cells or tissue fragments from a breast lesion and their analysis by a pathologist. There are several types of breast biopsy defined on the basis of the type of needle used: fine-needle aspiration and biopsy performed with a spring-based needle. This article focuses on fine-needle aspiration performed under sonographic guidance.

It is used mainly to assess cysts that appear to contain vegetations or blood or that are associated with symptoms; lesions and solid nodules that are not unequivocally benign; and axillary lymph nodes that appear suspicious on physical examination and/or sonography.

In addition to distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions, ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration also plays an important role in tumor grading and in immunocytochemical identifying specific tumor markers. This article describes the technique used and the possible causes of false negative and false positive findings. Despite its limitations, fine-needle aspiration has become a fundamental tool for the identification and preoperative management of malignant breast lesions.

Keywords: Breast, Ultrasonography, Fine-needle biopsy

Sommario

La biopsia delle lesioni della mammella consiste nel prelievo di alcune cellule, o di un frammento di tessuto, e nella successiva analisi anatomopatologica del materiale prelevato.

Esistono diversi tipi di biopsia della mammella, in particolare, a seconda del tipo di ago utilizzato, si possono distinguere: agoaspirato o aspirazione con ago sottile e biopsia con ago a scatto; nel presente articolo è presa in considerazione l’aspirazione con ago sottile, con guida ecografica.

Le principali indicazioni al prelievo sono: cisti con vegetazioni o con verosimile contenuto ematico e/o sintomatiche, lesioni, noduli solidi, la cui diagnosi non sia sicuramente benigna, linfonodi ascellari sospetti all’esame clinico e/o all’ecografia.

Oltre alla diagnosi di benignità o di malignità, l’agoaspirato con guida ecografica ha un ruolo rilevante nel grading e nell’identificazione, sulla scorta dei risultati immunocitochimici, di specifici marcatori delle neoplasie.

Dopo la descrizione della tecnica di esecuzione sono prese in considerazione le cause dei falsi positivi e di falsi negativi.

L’agoaspirazione, pur con i limiti esposti, rappresenta, quindi, una componente ormai fondamentale per la diagnosi di benignità o di malignità e nel management pre-operatorio delle lesioni mammarie.

Introduction

The biopsy of breast lesions involves the collection of cells or tissue fragments that will be analyzed by a pathologist. There are different types depending on the method used to sample the lesion. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) involves the collection of cells with a small-bore needle (Figs. 1–3). Core needle biopsies (CNB) are collected with a spring-loaded needle. A small fragment of tissue for histological analysis is taken from the suspicious zone with a special device known as a spring-loaded needle [1,2].

Figure 1.

FNAC of a symptomatic, cyst containing corpusculated fluid. Sonographic guidance allows the operator to visualize the advancement of the needle and verify the presence of the tip within the lesion (A). It also documents a progressive reduction of the cyst’s volume (B, C) and its ultimate disappearance (D).

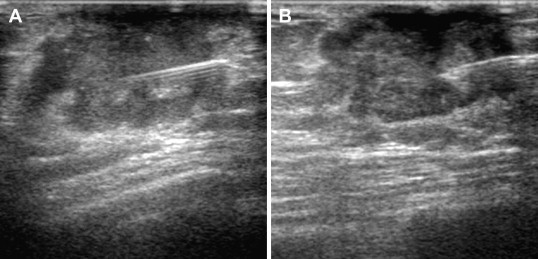

Figure 2.

FNAC of a malignant breast tumor. Sonographic guidance allows real-time visualization of the position of the needle. The tip can be moved in different directions to obtain multiple samples within the tumor (A, B).

Figure 3.

FNAC of a malignant tumor in a male patient. As in the female breast, sonographic guidance allows real-time verification of the needle position and collection of multiple samples within the tumor (A, B).

The present article focuses on the technique of fine-needle aspiration under sonographic guidance. The use of FNAC to diagnose carcinomas of the breast has become increasingly widespread thanks to its many advantages. It is a simple, low-cost procedure that can be performed rapidly; 2) it is not associated with any serious complications or adverse effects and is well tolerated by most patients; and 3) it is highly efficient, providing a diagnosis in approximately 80–90% of all cases [3]. Originally conceived of as a diagnostic procedure [4], FNAC has been used more recently to identify the biological characteristics of breast carcinomas, and its current applications include: characterization of lesions detected during screening, preoperative histological studies (Figs. 2 and 3) of tumors that will be treated surgically; immunocytochemical identification of specific tumor markers in lesions that will be managed medically. Cytological analysis of fine-needle aspirates can also be used to characterize cysts and solid nodules (palpable and nonpalpable, as shown in Figs. 3 and 2, respectively) and axillary lymph nodes.

The indications for FNAC are based largely on the patient’s age and medical history. FNAC is indicated when a lesion that is not unequivocally benign appears after the age of 30. In women under the age of 30, aspiration cytology is performed when a solid lesion displays rapid growth. In women < 36 years of age, mammography and ultrasonography exhibit limited sensitivity for diagnosing breast carcinomas, and these methods should be integrated with cytology to reduce the risk of false negatives. Cytology is not indicated for lesions that are clearly benign. These constitute a heterogeneous group of manifestations and the most frequent finding in women seen by physicians or radiologists [5].

Indications for biopsy

-

–

Cysts: FNAC is indicated in the presence of cysts that display endocystic vegetations, those whose content is probably hematic, and those associated with symptoms (Fig. 1).

-

–

Erosive lesions of the nipple: the examination is indicated when Paget disease is suspected.

-

–

Solid nodules: the examination is indicated in the presence of lesions that are not unequivocally benign (Fig. 2).

-

–

Axillary lymph nodes: FNAC is indicated when the nodes appear suspicious on clinical examination and/or ultrasound.

Technique

Fine-needle aspiration of a breast lesion for cytological analysis requires optimal, stable visualization of the lesion, and ultrasound guidance is the method of choice for achieving this end [6,7]. The skin is disinfected, and the needle is inserted near one of the short sides of the transducer and advanced along a trajectory lying parallel to the long axis of the transducer. The “fine” needles used for this procedure (outer diameter < 1 mm) are difficult to visualize on the monitor; for this reason the angle of incidence (with respect to the transducer) should be kept as small as possible. The use of smaller-gauge needles may be indicated for nonpalpable masses; for fibrous lesions better results can probably be obtained with needles measuring up to 0.90 mm. Ultrasound guided needle aspiration requires the following equipment and materials: disposable needles (21-27 gauge); a disposable 20-ml syringe; skin disinfectant; ground glass slides; slide holders; and fixatives.

For deep nodules, the needle should be inserted somewhat farther away from the edge of the transducer, keeping in mind, however, the overall length of the needle. The access point must be close enough to the transducer to ensure that the needle tip can penetrate the lesion with ease. Access through the areola should be avoided, when possible, as it is more painful for the patient. Some operators prefer an access point that is always on the same side of the monitor screen, and they will rotate the transducer 180° to obtain this if necessary. There is no real difference between the two methods: the choice depends on the personal preferences of the operator.

The needle should be clearly visualized on the monitor as it advances, and the presence of the tip within the lesion should be unequivocally verified. Once the needle has penetrated the nodule, aspiration is applied, and the tip is moved in different directions to collect multiple samples. No aspiration is applied while the needle is being withdrawn. Negative pressure in the syringe during withdrawal increases the risk of tumor seeding and adds nonlesional material to the specimen, which diminishes its representativeness. The capillarity of the needle can be exploited to collect the sample or aspiration can be used; in the latter case the needle obviously has to be attached to a syringe. Negative pressure is applied once the needle has been positioned. It is maintained during sampling (carried out with small back-and-forth movements in different directions) and gently released before the needle is withdrawn. The material collected should be used to prepare at least two slides: one for Papanicolaou staining (after fixation in 95% ethanol), and one that will be air-dried and stained with May-Grunwald Giemsa stain.

Unlike malignant nodules, benign lumps are highly mobile. In these cases, the nodule can sometimes be stabilized by inclining the transducer slightly and applying pressure that opposes the thrust of the needle. If the mass is large, the tip of the needle should remain in the periphery since the central zones will often be necrotic. As an added precaution, the nodules can be examined before the biopsy with color Doppler. This reveals highly vascularized areas of the lesions, which should be avoided during sampling to minimize the risk of contaminating the specimen with blood cells. During collection, the area around the needle tip should be constantly checked for evidence of bleeding caused by accidental puncture of a vessel.

The aspirated material is immediately smeared onto the slides and sprayed with an appropriate fixative. Regardless of the technique used to collect the cytological specimen, the results are classified into 5 diagnostic categories in accordance with European guidelines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diagnostic categories recommended by European guidelines.

| Diagnostic category | Results | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Inadequate/non-representative | Nonoptimal for diagnosis/number of epithelial cells too low |

| C2 | Benign | Aspirate adequate for diagnosis and with benign features |

| C3 | Atypia in a lesion that is probably benign | Aspirate adequate for diagnosis and with benign features couple with some cellular atypia |

| C4 | Suspected malignancy or probable carcinoma | Aspirate that is suggestive of malignancy without being definitively diagnostic |

| C5 | Malignant carcinoma or other malignant tumor | Aspirate containing cells with features of carcinoma or other malignant tumors |

Discussion and conclusions

Fine-needle aspiration cytology is highly sensitive (65–99%) and specific (96–100%) with a predictive value of approximately 99% [8–11].

The reported percentages of specimens that are inadequate or false negatives (which have an impact on sensitivity) [12,13] vary from 0% to 35%, and they are particularly high in facilities where biopsies are performed by clinicians instead of pathologists.

Apart from the absence of the pathologist at the time of biopsy, other factors can also be associated with sample inadequacy and false negativity. The most important of these are related to the position of the needle within the lesion, lesion inhomogeneity, and the experience of the cytopathologist.

Malignancy can be diagnosed with certainty only if the smear meets the following criteria:

-

1.

abundant cellularity

-

2.

unequivocal signs of malignancy

-

3.

evidence of poor cohesion.

Even when these guidelines are followed, false positivity can occur (e.g., in the presence of fibroadenomas, which are difficult to distinguish from phyllodes tumors on the basis of cytological samples) [14–16].

The 2% sensitivity deficit (with respect to optimal levels) is related to the presence of tumors like tubular and lobular carcinomas, which are characterized by low cellularity (due to their extensive collagen and stromal components) and small tumor cells with relatively normal-appearing nuclei, factors that often preclude a definitive diagnosis [17–19].

The diagnostic role of breast sonography has been expanded to include morphological differentiation of benign and malignant lymph nodes and imaging guidance for the biopsy of those that are pathological. Ultrasonography combined with FNAC has displayed excellent specificity (up to 100%) in diagnosing metastases, and it can significantly reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies of sentinel lymph nodes.

The authors of most studies conducted thus far have used FNAC instead of CNB for the preoperative detection of axillary lymph nodes. The reported sensitivity of FNAC ranged from 21% to 95% (similar results—from 40% to 90%—have been reported for CNB, but in a smaller number of studies). It is generally felt that that the FNAC technique that provides for multiple passages through the nodule offers certain theoretical advantages in terms of sensitivity. In addition, CNB is a more aggressive, higher-risk procedure than FNAC, although it is also less operator-dependent [20].

The most important information for clinicians who are planning treatment (aside from the diagnosis) is the grade of the tumor, particularly in cases where surgery is not the treatment of choice. FNAC has proved to be an accurate tool for tumor grading, which is generally based on the nuclear grading system proposed by M.M. Black and colleagues (in some cases with modifications) [21]. New and colleagues [22] have proposed a cytologic grading system, which assesses the size of the nucleus (using the mean diameter of a red blood cell as a reference); nuclear polymorphism; and the presence/absence of the nucleus. It displays good correlation with the histologic grading system of Elston [23,24].

When the initial treatment consists of chemotherapy rather than surgery, immunocytochemical analysis of the aspirate to identify specific tumor markers can be very useful.

In conclusion, because of the variety and complexities of the diseases that affect it, the breast is the most frequently biopsied organ. Fine-needle aspiration is now a fundamental part of the preoperative work-up of breast lesions.

To ensure optimal results, however, clinicians, pathologists, and radiologists must collaborate closely to direct diagnostic procedures with rigor, accuracy, and respect for the indications, appropriate precautions, and contraindications for this procedure, which are essential for safeguarding the patient and the physician.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Shulman S.G., March D.E. Ultrasound-guided breast interventions: accuracy of biopsy techniques and applications in patient management. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2006 Aug;27(4):298–307. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schueller G., Schueller-Weidekamm C., Helbich T.H. Accuracy of ultrasound-guided, large-core needle breast biopsy. Eur Radiol. 2008 Sep;18(9):1761–1773. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilotti S. L’aspirazione con ago sottile nell’accertamento di noduli palpabili e non della mammella. In: Veronesi U., Coopmans de Yodi G.F., editors. vol. 21. EDIMES; Pavia: 1997. pp. 144–153. (Senologia Diagnostica per immagini). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poma S., Longo A. The clinician’s role in the diagnosis of breast disease. J Ultras. 2011;14:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masciadri N., Ferranti C. Benign breast lesions: ultrasound. J Ultras. 2011;14:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draghi F., Robotti G., Jacob D., Bianchi S. Interventional musculoskeletal ultrasonography: precautions and contraindications. J Ultras. 2010;13:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Flynn E.A., Wilson A.R., Michell M.J. Image-guided breast biopsy: state-of-the-art. Clin Radiol. 2010 Apr;65(4):259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giard R.W., Hermans J. The value of aspiration cytologic examination of the breast. A statistical review of the medical literature. Cancer. 1992;69:2104–2110. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2104::aid-cncr2820690816>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Layfield L.J., Glasgow B.J., Cramer H. Fine needle aspiration in the management of breast masses. FNA Management of breast masses. Pathol Annu. 1989;2:23–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Pietro S., Fariselli G., Bandieramonte G., Coopmans de Yoldi G., Guzzon A., Viganotti G. Systematic use of the clinical-mammographic-cytologic triplet for the early diagnosis of mammary carcinoma. Tumori. 1985;71:179–185. doi: 10.1177/030089168507100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermansen C., Skovgaard Poulsen H., Jensen J., Langfeldt B., Steenskov V., Frederiksen P. Diagnostic reliability of combined physical examination, mammography and fine needle puncture ("triple test") in breast tumors. A prospective study. Cancer. 1987;60:1866–1871. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871015)60:8<1866::aid-cncr2820600832>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Layfield L.J. Can fine-needle aspiration replace open biopsy in the diagnosis of palpable breast lesions? Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98:145–147. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/98.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layfield L.J., Chrischilles E.A., Cohen M.B., Bottles K. The palpable breast nodule. A cost-effectiveness analysis of alternate diagnostic approaches. Cancer. 1993;72:1642–1651. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930901)72:5<1642::aid-cncr2820720525>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Kaisi N. The spectrum of the "Gray Zone" in breast cytology. A review of 186 cases of atypical and suspicious cytology. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottles K., Chan J.S., Holly E.A., Chiu S.H., Miller T.R. Cytologic criteria for fibroadenoma. A step-wise logistic regression analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:707–713. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/89.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sneige N. Fine needle aspiration of the breast. A review of 1,995 cases with emphasis on diagnostic pitfalls". Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9:106–112. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840090122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisenberg A.J., Hajdu S.I., Wilhelmus J., Melamed M.R., Kinne D. Preoperative aspiration cytology of breast tumors. Acta Cytol. 1986;30:135–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hitchcock A., Hunt C.M., Locker A., Koslowski J., Strudwick S., Elston C.W. A one year audit of fine needle aspiration cytology for the pre-operative diagnosis of breast disease. Cytopathology. 1991;2:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1991.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leach C., Howell L.P. Cytodiagnosis of classic lobular carcinoma and its variants. Acta Cytol. 1992;36(2):199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojeda-Fournier H., Nguyen J.Q. Ultrasound evaluation of regional breast lymph nodes. Semin Roentgenol. 2011 Jan;46(1):51–59. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black M.M., Speer F.D. Nuclear structure in cancer tissues. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;105:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.New N.E., Howat A.J. Nuclear grading of breast carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 1994 Nov–Dec;38(6):969–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elston C.W. Classification and grading of invasive breast carcinoma. Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 2005;89:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elston C.W., Ellis I.O. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991 Nov;19(5):403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.