Abstract

Testicular ischemia is a rare complication of inguinal hernia repair. It results from the injury to the vessels that course along the inguinal canal. Typically it is painful at the beginning and asymptomatic later. Ultrasonographic appearance and aspects of testicular ischemia result in diffusely hypoechoic and disomogeneous testis, with complete lack of intratesticular vascular signal on color-Doppler and cremasteric vessels hypertrophy in chronic cases.

This report describes a testicular ischemia seen in a patient referred to because of hernia recurrence, without any sign or symptom of acute scrotum. Ultrasound examination showed the most frequent complications after inguinal hernia repair: both hernia recurrence and testicular ischemia.

Keywords: Testicular ischemia, Ultrasonography, Color-Doppler, Inguinal hernia repair

Sommario

L'ischemia testicolare è una delle rare complicanze dell'intervento chirurgico di ernioplastica inguinale. É dovuta a compromissione della vascolarizzazione dei vasi che decorrono nel canale inguinale e si manifesta con dolore, per poi diventare asintomatica. Ecograficamente il testicolo appare ipoecogeno, con struttura modicamente disomogenea e assenza di vascolarizzazione alla valutazione color Doppler; nei casi cronici può essere presente ipertrofia dei vasi cremasterici.

Viene presentato un caso di ischemia testicolare post-intervento chirurgico di ernioplastica, in paziente giunto alla nostra osservazione nel sospetto di recidiva d'ernia, senza sintomi di scroto acuto. L'esame ecografico ha mostrato la presenza di entrambe le complicanze post-intervento più frequenti: recidiva d'ernia ed ischemia testicolare.

Introduction

Three main vessels provide the arterial supply of the scrotal contents. The internal spermatic artery, a branch of the abdominal aorta, courses along the inguinal canal and divides into two main branches: testicular and epididymal. The testicular artery penetrates the tunica albuginea in the vicinity of the lower pole, forming the capsular artery; branches of the capsular artery course in the septations of the testicular parenchyma as centripetal arteries; recurrent or centrifugal arteries course from the mediastinum to the periphery, inside the parenchyma. The epididymal branch supplies the epididymis. The external spermatic artery, also called cremasteric artery, is a branch of the inferior epigastric artery and it supplies the coverings of the cord. The deferential artery originates from the superior vesical artery and supplies the deferent duct. Smaller branches of the internal and external pudendal arteries also contribute to the arterial supply of the coverings of the testes. Multiple anastomoses develop between the three main branches, mainly at the level of the cord and on the surface of the epididymis. The venous drainage of the testis is accomplished through the plexus pampiniformis. As they course through the cord and along the inguinal canal, the venous channels of the plexus join to form the internal spermatic vein draining directly into the inferior vena cava on the right side and the left renal vein, on the left side. The smaller posterior spermatic plexus, or cremasteric plexus, drains the epididymis in the external spermatic vein [1].

On color Doppler, both centripetal and centrifugal arteries are seen as short vessels or simple color dots. Transtesticular arteries are seen in approximately 50% of the subjects, as thicker and relatively long vessels that cross the testicular parenchyma; they may be asymmetric and are observed, more frequently, in the upper third of the testis. Half of them are accompanied by a vein. Flow in these arteries may be either centripetal or centrifugal. On colour Doppler the epididymis shows almost no vascularity [2].

Classically, the diagnosis of testicular ischemia is clinically established and confirmed by color or power Doppler when there is no detectable flow within the testicular parenchyma. In subacute or chronic phases peritesticular hyperemia occurs, due to the anastomoses with epididymal and deferential arteries.

Complications after inguinal hernia repair occur in 1.7%–8% of all cases. Recurrence of hernia is the most common complication and occurs in 0.3%–3.8% of cases, followed by injury to the vas deferens (1.6%) and injury to the vessels, in particular injury to the spermatic vessels can result in ischemic orchitis and lead to testicular atrophy (0.2%–1.1% of all inguinal hernia repairs). Unusual complications include testicle entrapment in the inguinal canal, wound infections, ilio-inguinal, ilio-hypogastric and genitofemoral nerve damage [3,4].

Case report

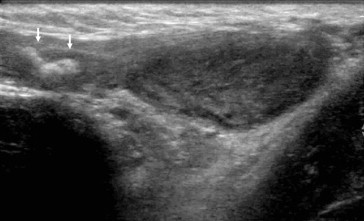

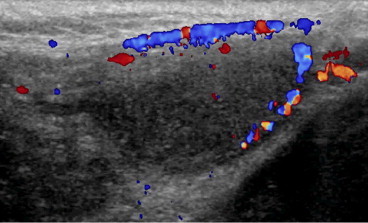

The patient is a 80-year-old Caucasian male who was referred because of a suspicion of recurrence of inguinal hernia. Six months before the patient underwent a mesh implantation to treat a left inguinal hernia. His physical testicular examination was essentially unremarkable. The ultrasonographic examination showed the recurrence of left inguinal hernia, right inguinal hernia and diffusely hypoechoic left testis (Fig.1). On color Doppler no detectable flow within the testicular parenchyma was seen but cremasteric vessels hypertrophy (Fig. 2) and peritesticular hyperemia were noted. This pattern highly suggested a testicular chronic ischemia. Color Doppler evaluation also showed bilateral varicocele.

Figure 1.

Testicular ischemia as hernia repair complication. Ultrasonography shows an inhomogeneous and hypoechoic testicular signal; a bowel loop is seen (arrows) in the scrotum as recurrence of hernia.

Figure 2.

Testicular ischemia as hernia repair complication. On color Doppler there is a complete lack of intratesticular vascular signal and cremasteric vessel hypertrophy.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Conclusions

Spermatic cord torsion is the most common cause of testicular ischemia. Testicular ischemia, less frequently, can be secondary to severe epididymitis with vessel compression, inguinal hernia repair, spontaneous thrombosis of funicular vessels, xanthogranulomatous or filarial funiculitis [5].

Regardless of the cause, ultrasonographic appearance and aspects of testicular ischemia result in volume increase during acute-subacute phases and volume reduction during the chronic phase. Testicular parenchyma appears hypoechoic (Fig.1), with no detectable flow on color Doppler (Fig. 2). Hypertrophy of cremasteric vessels can be seen in chronic phases.

We considered appropriate to present this case since it confirms the typical good sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography in scrotal injuries evaluation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix. Supporting information

References

- 1.Martinoli C., Pastorino C., Bertolotto M., Rosenberg I., Cittadini G., Garlaschi G. Color-Doppler echography of the testis. Study technique and vascular anatomy. Radiol Med. 1992;84:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudea S.M., Ciurea A., Chiorean A., Botar-Jid C. Doppler applications in testicular and scrotal disease. Med Ultrason. 2010;12:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier A.H., Ricketts R.R. Surgical complications of inguinal and abdominal wall hernias. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2003;12:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s1055-8586(02)00015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridgway P.F., Shah J., Darzi A.W. Male genital tract injuries after contemporary inguinal hernia repair. BJU Int. 2002;90:272–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pepe P., Aragona F. Testicular ischemia following mesh hernia repair and acute prostatitis. Indian J Urol. 2007 Jul;23(3):323–325. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.33736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.