Abstract

The male breast has been insufficiently explored in the medical literature, particularly that dealing with ultrasonography, although this topic is almost as vast and varied as that of the female breast. The purpose of this article is to provide a schematic review of the most frequent breast lesions encountered in males and their sonographic appearances. After a brief introduction on the anatomy of the male breast, the authors review the non-neoplastic (gynecomastia, pseudogynecomastia, cysts, inflammatory diseases, and Mondor disease) and neoplastic (benign and malignant) lesions encountered in this organ.

Keywords: Breast, Male breast, Ultrasonography

Sommario

La mammella maschile, seppur scarsamente trattata nella letteratura medica e in particolare in quella ecografica, rappresenta un argomento vasto e vario quasi quanto lo è la mammella femminile. Scopo di questo lavoro è inquadrare in modo schematico ed esaustivo le più frequenti lesioni mammarie nell’uomo e i rispettivi aspetti ecografici. Dopo una breve introduzione relativa all’anatomia della mammella maschile sono valutate prima le lesioni non neoplastiche, tra cui la ginecomastia, la pseudoginecomastia, le cisti, le patologie infiammatorie e la malattia di Mondor, quindi le neoplasie benigne e, in ultima istanza, quelle maligne.

Introduction

The medical literature has concentrated mainly on the female breast and its disorders. The male breast has attracted less attention, in part because it is a rudimentary, non- functional organ and in part because it is less frequently targeted by disease. However, the male breast can be the site of a wide variety of benign and malignant lesions, which have to be known for correct diagnosis and treatment [1].

Physical examination and mammography are the methods of choice for evaluating lesions of the female breast, particularly those of a neoplastic nature. Ultrasonography is used only as complementary examination (except in certain cases, such as clinically benign lesions in young women, lumps that develop during pregnancy) or as a guide for biopsy. The male breast is also evaluated largely by means of clinical examination, and the various diseases that affect it have characteristics similar to those of the female breast. Because of its limited volume, the male breast is not easy to examine with mammography. Nevertheless, many still consider it the method of choice for supplementing the clinical examination of this organ [1]. Ultrasound is highly effective for exploring isolated lesions, and it is becoming the natural complement for the diagnostic work-up.

Mammography is undoubtedly superior to ultrasound for the identification and characterization of microcalcifications, but these are quite rare in the male breast. Ultrasound has an established role as a guide for biopsy of breast lesions in males or females. It allows real-time visualization of the needle tip and can also provide information on lesion vascularization, which can be used to select the area that should be sampled. In this article, we review the sonographic features of various benign and malignant lesions of the male breast.

Anatomy

The mammary gland is located between the pectoral muscles and the subcutaneous tissues.

It is composed largely of adipose tissue with a small, flattened, disc-shaped body of grayish, fibrous glandular tissue. This body consists of 15–25 short, branched lactiferous ducts, whose minute orifices open onto the apex of the nipple. Normally, lobular formations are absent, as are the ligaments of Cooper. The arterial blood supply comes from the main external artery of Salomon, which originates from the axillary artery, the internal mammary artery (also known as the internal thoracic artery), and branches of the third, fourth, and fifth intercostal arteries. Venous drainage is provided by two vessels, one superficial, the other deep, which converge and empty into the intercostal veins. Lymphatic drainage is furnished mainly by the axillary lymph nodes and to a lesser extent by the supraclavicular and internal thoracic nodes. The breast contains mainly sensory nerve endings derived from the intercostal and supraclavicular nerves.

On ultrasound, the nipple appears as a small hyperechoic nodule with mild posterior attenuation; when visible, the small volume of glandular tissue appears hypoechoic (Fig. 1). The overlying skin is hyperechoic, and the subcutaneous tissue (like most subcutaneous fat) is hypoechoic with hyperechoic streaks that represent fibrous striae.

Fig. 1.

Sonographic appearance of the male breast under physiological conditions: Superficially, the nipple is seen as an oval, hyperechoic formation with minimal posterior attenuation. Below it lies a small amount of glandular tissue, which appears hypoechoic with respect to the nipple.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia refers to an enlargement of the male breast caused by benign proliferation of the glands ducts and stromal components. It is the most common form of breast swelling seen in males. Some forms of gynecomastia are physiological or paraphysiological. In the perinatal period [2,3] male breast enlargement can be caused by transplacental exposure to maternal estrogens. During puberty, it can develop as a result of hormonal instability caused by imbalances between blood levels of testosterone and estrogens. And in adults (60–80 year olds), gynecomastia can be caused by diminished androgen secretion associated with reduced inactivation of estrogens in the liver.

Gynecomastia can also be associated with diverse pathological conditions, including Leydig cell tumors of the testis; adrenal tumors; ectopic production of gonadotropin by tumors of the lung, liver, or kidney; liver or renal failure; and hyperthyroidism. Last but not least, gynecomastia can be an adverse effect of certain drugs like steroid hormones, cimetidine, thiazide diuretics, cardiac glucosides, antihypertensives, antidepressants, and narcotics [4]. Cases have also been linked to the illegal use of anabolic steroids, particularly by professional athletes [5].

Clinical manifestations consist of a soft, elastic, nodule-like retroareolar mass that is occasionally associated with pain. The overlying skin is intact and resembles that of adjacent areas.

Three types of gynecomastia have been described: nodular (Fig. 2), dendritic (Fig. 3) and diffuse glandular (Fig. 4). Each represents a different degree of ductal and stromal proliferation. The nodular and dendritic forms correspond to the florid and fibrous stages of proliferation, respectively, whereas the diffuse glandular type corresponds to epithelial proliferation and is often linked to the use of exogenous hormones.

Fig. 2.

Nodular gynecomastia: The lesion appears as a solid, retroareolar mass with a homogeneously hypoechoic echo texture and well-defined margins.

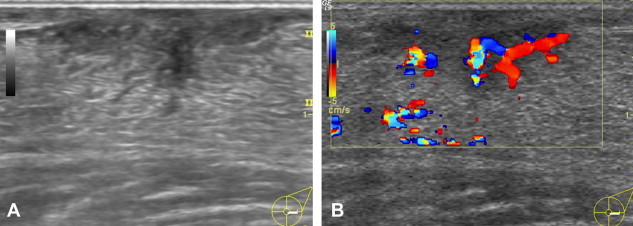

Fig. 3.

Dendritic gynecomastia: The lesion appears as a triangular, hypoechoic retroareolar mass with branches extending into the peripheral adipose tissue (A). Moderate vascularity is seen on the color Doppler examination (B).

Fig. 4.

Diffuse glandular gynecomastia: Glandular tissue is diffusely distributed within the adipose tissue in a pattern resembling that of the female breast.

The ultrasound examination reveals a subareolar hypoechoic mass, which may have typical nodular features and a long axis that is parallel to the skin (nodular gynecomastia) (Fig. 2), or it may be triangular with extensions that radiate into the subareolar fat (dendritic gynecomastia) (Fig. 3), or it may resemble a female breast (diffuse gynecomastia) (Fig. 4). The color-Doppler evaluation reveals moderate, harmonious intralesional vascularization (Fig. 3B) [6].

Pseudogynecomastia

Pseudogynecomastia involves breast enlargement (usually bilateral) caused by an excess of adipose tissue, which is not necessarily associated with constitutional obesity [7,8] or with alterations of the breast parenchyma, whose volume is normal. It is clinically manifested by increases in volume that are diffuse, non-nodular, and symmetrical. The diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Ultrasonography reveals the presence of lobular areas of adipose tissue that are homogeneously hypoechogenic and separated from one another by thin hyperechoic bands of fibrous tissue (Fig. 5) [1].

Fig. 5.

Pseudogynecomastia: Ultrasonography shows multiple lobules of fat with a homogeneously hypoechoic echo structure. The lobules are separated by thin branches of hyperechoic fibrous tissue posterior to the nipple. The latter is seen as an oval-shaped hyperechoic structure with moderate posterior attenuation.

Cysts

Breast cysts, which are relatively rare, are caused by dilatation of the ducts. The cells composing the ductal epithelium often have abundant, eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm and roundish hyperchromic nuclei. The epithelium resembles that of the apocrine sweat glands. The secretions may be calcified.

In men, breast cysts are often associated with gynecomastia, and they are generally solitary lesions. For this reason, they cause greater alarm, particularly those with a firm consistency that are relatively fixed to underlying structures.

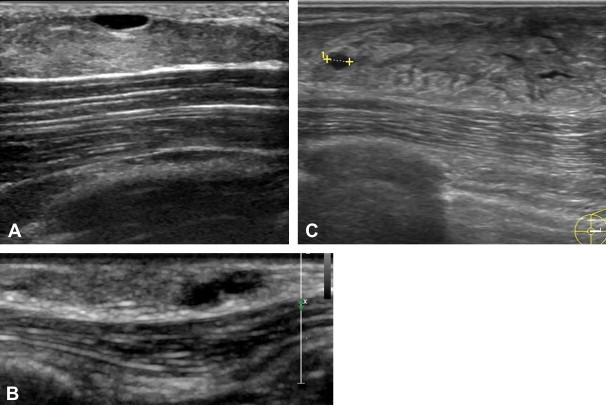

As in females, breast cysts can be simple, complicated, or complex. On ultrasound, simple cysts are characterized by well-defined margins, anechoic contents, reinforcement of the posterior wall, and lateral acoustic shadows (Fig. 6). Color-Doppler may reveal perilesional signals related to compression and/or dislocation of nearby vascular structures. Complicated or complex cysts are hypo-anechoic with well-defined margins. They often contain numerous small hyperechoic formations or true vegetations. In corpuscular cysts, color Doppler may reveal intralesional signals caused by motion artifacts.

Fig. 6.

A. Simple cysts in a patient with pseudogynecomastia: Ultrasonography shows abundant adipose tissue containing anechoic structures with well-defined margins and posterior acoustic enhancement. B. Simple cysts in a patient with nodular gynecomastia: Ultrasonography reveals two anechoic formations that adhere to one another, both with well-defined margins and posterior acoustic enhancement. C. Simple cysts in a patient with dendritic gynecomastia: Ultrasonography shows an anechoic formation with well-defined margins and posterior acoustic enhancement (caliper).

Inflammatory conditions

Mastitis, which is also relatively rare, is an inflammatory process caused by bacteria such as staphylococci or less commonly streptococci. The organisms enter the gland through the nipple as a result of trauma (e.g., nipple piercing). Mastitis is associated with the typical signs of local inflammation: pain, erythema, heat, skin thickening, and edema.

Subareolar abscesses are the most common inflammatory lesions encountered in the male breast. They are often the localized result of chronic mastitis. The abscesses tend to recur if they are not adequately treated and may require surgical excision that extends to the related ducts [7,9]. The clinical features of an abscess are often similar to those of a neoplastic lesion, and the diagnosis is often based on combined data from the patient history, breast examination, and imaging studies.

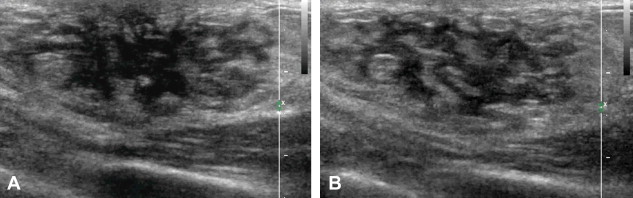

On ultrasonography, the mastitic male breast resembles a female breast with diffuse edema, thickening of the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 7A,B), and color Doppler evidence of hypervascularization (Fig. 7C,D). Abscesses appear as hypo- to anechoic lesions with irregular margins and peripheral vascularization [10,11].

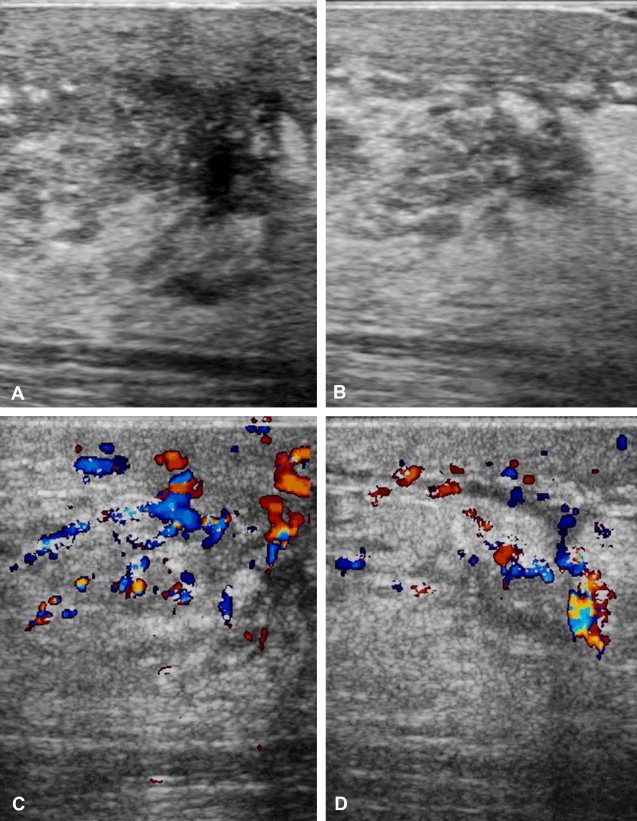

Fig. 7.

Mastitis in a patient with gynecomastia. The infection developed following a biopsy procedure performed under non-aseptic conditions. Ultrasonography shows thickening of the skin and subcutaneous layers, diffuse edema (A, B). Color Doppler reveals hypervascularization (C, D).

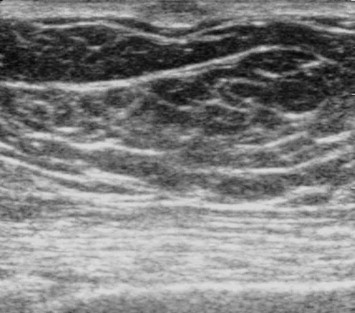

Mondor disease

Mondor disease (Fig. 8) is a relatively rare form of thrombophlebitis that involves the subcutaneous veins of the anterior chest wall [1,2]. It manifests clinically as a subcutaneous, cord-like lesion, which is initially soft and red. Later, it becomes firm and painful, and the overlying skin is tense and/or retracted. Mondor disease is frequently associated with breast cancer, but there are also a number of other causes including trauma, venous catheterization, the use of intravenous drugs and, in general, any situation that causes vein trauma or venous stasis with increased pressure on the walls of the veins. In cases of Mondor disease in which there is no apparent cause, the pathophysiological mechanism appears to be related to repeated stretching of the venous walls secondary to the continual movement of the chest wall that occurs with contractions of the pectoral muscles [12]. The disease can affect one or more veins, including the thoracoepigastric vein, lateral thoracic vein, and the superior epigastric vein. The sonographic appearance is that of a slender, hypoechoic cord whose walls are thick and hyperechoic (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Mondor disease: Ultrasound reveals a thrombosed vein (A). that resists compression by the probe (B) the color-Doppler study reveals only minimal residual flow (C).

Lipomas

The lipoma is the second most common benign lesion in the male breast [4].

It is a well-defined, encapsulated mass containing adipocytes. It is usually asymptomatic and presents as a small, palpable mass that may be soft or (when calcified) hard. Ultrasound reveals a well-circumscribed lesion that is homogeneously isoechoic or slightly hyperechoic (Fig. 9) with respect to the subcutaneous fat. The mass is surrounded by a thin, echogenic capsule and is not associated with posterior shadowing or contrast-enhancement during examination with acoustic contrast medium. Small lipomas may appear hyperechoic [11], and those that are calcified and hyperechoic may exhibit posterior shadowing.

Fig. 9.

Lipoma: Ultrasonography reveals a well-circumscribed, homogeneous mass that is slightly hyperechogenic with respect to the subcutaneous fat. Its long axis lies parallel to the cutaneous layer. The mass is surrounded by a thin, hyperechoic capsule, and there is no posterior shadowing.

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas are rare in the male breast owing to the absence of glandular lobules. Very few cases have been described, and many of these have developed during estrogen stimulation [13–15]. The sonographic features are similar to those of fibroadenomas in the female breast. Sonographically, the lesion appears as an oval, hypoechoic formation that is circumscribed, with well-defined margins and in some cases macrolobulations (Fig. 10A) [4]. Examination with color Doppler shows vascularization, which generally consists of one or two vessels that penetrate the parenchyma of the lesion and have harmonically distributed terminal branches (Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

Fibroadenoma: Ultrasonography reveals a circumscribed, oval-shaped, lobulated mass that is inhomogeneously hypoechoic (fibroadenoma with areas of myxoid degeneration) with well-defined margins (A). Color Doppler reveals multiple vascular poles but the vascularization is harmonious (B).

Malignant tumors

Breast malignancies are relatively rare in males. The commonly occur as localized, painful masses and are usually found at the subareolar level or in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Compared with gynecomastia, these lesions are often eccentric with respect to the nipple. The mass may be attached to the skin or the pectoral muscle. Other clinical presentations include nipple retraction and bloody discharge from the nipple. Several risk factors have been identified for male breast cancer including age, family history (BRCA2), exposure to radiation, cryptorchidism, testicular injury, Klinefelter syndrome, liver dysfunction, and chest trauma [4]. The most common forms are invasive ductal carcinoma (85% of cases), papillary carcinoma (5%), and lymphoma [16]. On ultrasound, invasive ductal carcinoma appears as a solid mass, which is usually hypoechoic (Fig. 11). Less frequently it may appear as a complex cyst or as an area of distortion. In all cases, it has irregular margins and more or less intense posterior attenuation rear [4]. Some lesions are hypervascular. Papillary carcinoma appear as solid or complex cystic masses with thick walls that contain both solid and cystic components [17–19]. As for primary lymphoma of the breast, it may appear as a solid, roundish, hypoechoic mass with irregular or microlobulated margins. These tumors are usually hypervascular.

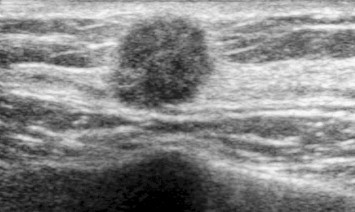

Fig. 11.

Neoplasm: Ultrasonography reveals a solid nodule with a large central nucleus and irregular, infiltrating margins.

Discussion and conclusions

Gynecomastia and pseudogynecomastia have a significant incidence that is slowly but steadily increasing, with cases of pseudogynecomastia in adolescents and cases of true gynecomastia in young adults using anabolic substances and elderly patients with cancer of the prostate who are on hormone therapy [1,3,5,6]. Pseudogynecomastia is diagnosed on the basis of findings obtained through breast palpation: ultrasonography merely confirms the clinical diagnosis. Ultrasonography is more important in the diagnosis of true gynecomastia, which has a clinical presentation very similar to that of other nodular diseases. Tumors of the male breast are uncommon [1,7–10], as are most other lesions involving this organ. For this reason, there is a fairly limited amount of literature on these lesions. However, professionals performing ultrasound examinations of the breast need to be familiar with them. For one thing, the use of mammography is decreasing in male patients. In contrast, ultrasonography, together with history and physical examination, can generally provide a diagnosis and assess treatment outcomes. Biopsy, which is always performed with ultrasound guidance, can be reserved for those few cases in which doubts arise or when drainage is required [1].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data related to this article

References

- 1.Draghi F. In: Eco color-Doppler della mammella maschile. Draghi F., Fachinetti C., Ferrozzi G., Madonia L., editors. 2004. pp. 13–22. Athena. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesur Y., Caksen H., Demirtas I., Kosem M., Uner A., Ozer R. Bilateral galactocele in a male infant: a rare cause of gynecomastia in childhood. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14(1):107–109. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson R.E., Murad M.H. Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60671-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stavros A.T. Breast ultrasound. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. Evaluation of the male breast; pp. 712–741. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahrke M.S., Yesalis C.E. Abuse of anabolic androgenic steroids and related substances in sport and exercise. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4(6):614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlandi M.A., Venegoni E., Pagani C. Gynecomastia in two young men with histories of prolonged use of anabolic androgenic steroids. JUS. 2010;13:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Günhan-Bilgen I., Bozkaya H., Ustün E.E., Memiş A. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246–255. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart R.A., Howlett D.C., Hearn F.J. Pictorial review: the imaging features of the male breast disease. Clin Radiol. 1997;52(10):739–744. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boring C.C., Squires T.S., Tony T., Montgomery S. Vol. 44. 1994. Cancer statistics; pp. 7–26. (CA cancer J Clin). 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appelbaum A.H., Evans G.F., Levy K.R., Amirkhan R.H., Schumpert T.D. Mammographic appearances of male breast disease. Radiographics. 1999;19:559–568. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.3.g99ma01559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yitta S., Cl Singer, Toth H.B., Mercado C.L. Image presentation. Sonographic appearances of benign and malignant male breast disease with mammographic and pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:931–947. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.6.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan G.F. Mondor’s disease. Arch Intern Med. 1964;113:881–885. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1964.00280120081015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemmo G., Garcea N., Corsello S., Tarquini E., Palladino T., Ardito G. Breast fibroadenoma in a male-to-female transsexual patient after hormonal treatment. Eur J Surg Suppl. 2003;588:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanhai R.C., Hage J.J., Bloemena E., van Diest P.J., Karim R.B. Mammary fibroadenoma in a male-to-female transsexual. Histopathology. 1999;35:183–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.0744c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansah-Boateng Y., Tavassoli F.A. Fibroadenoma and cystosarcoma phyllodes of the male breast. Mod Pathol. 1992;5:114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathew J., Perkins G.H., Stephens T., Middleton L.P., Yang W.T. Primary breast cancer in men: clinical, imaging, and pathologic findings in 57 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1631–1639. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L., Chantra P.K., Larsen L.H., Barton P., Rohitopakarn M., Zhu E.Q. Imaging characteristics of malignant lesions of the male breast. Radiographics. 2006;26:993–1006. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W.T., Whitman G.J., Yuen E.H., Tse G.M., Stelling C.B. Sonographic features of primary breast cancer in men. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:413–416. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knelson M.H., El Yousef S.J., Goldberg R.E., Balance W. Intracystic papillary carcinoma of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, and MR appearance with pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11:1074–1076. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198711000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.