Abstract

C-terminal peptide thioesters are an essential component of the native chemical ligation approach for the preparation of fully- or semi-synthetic proteins. However, efficient generation of C-terminal thioesters via Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis remains a challenge. The recent N-acylurea approach to thioester synthesis relies on deactivation of one amine of 3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Dbz) during Fmoc-SPPS. Here, we demonstrate that this approach results in the formation of side products by over-acylation of Dbz, particularly when applied to Gly-rich sequences. We find that orthogonal allyloxycarbonyl (Alloc) protection of a single Dbz amine eliminates these side products. We introduce a protected Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) base resin that may be directly used for synthesis with most C-terminal amino acids. Following synthesis, quantitative removal of the Alloc group allows conversion to the active N-acyl-benzimidazolinone (Nbz) species, which may be purified and converted in situ to thioester under ligation conditions. This method is compatible with automated preparation of peptide-Nbz conjugates. We demonstrate that Dbz protection improves synthetic purity of Gly-rich peptide sequences derived from histone H4, as well as a 44-residue peptide from histone H3.

Keywords: solid-phase synthesis, peptides, peptide thioesters, native chemical ligation

Introduction

Thioester peptides are a central requirement for native chemical ligation, often used for the synthesis and semi-synthesis of proteins for biochemical and biophysical studies.[1] Techniques for the preparation of peptide thioesters are of ongoing interest to the field of chemical biology. Thioester peptides are readily synthesized via solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) employing Boc protection strategies by direct installation of a thioester linkage on the resin.[2] However, this approach is not compatible with Fmoc protocols common for automated peptide synthesis because the thioester linkage is labile under basic conditions. A variety of methods have been developed for the generation of thioesters,[3] but no single method has yet proven dominant.[4]

Recently, Blanco-Canosa and coworkers introduced an elegant new approach for the preparation of peptide thioesters through the use of a 3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Dbz) linker that may be chemically modified after synthesis to afford an N-acylurea moiety on resin (Scheme 1).[5] Key to this method is the control of chain extension such that acylation occurs at only one of the two unprotected amines on the Dbz linker. Subsequent to the initial acylation, the second amine is ideally rendered unreactive by a combination of electronic and steric effects. Following peptide synthesis, the remaining Dbz amine is reacted with p-nitrophenylchloroformate and rearranges to an N-acyl-benzimidazolinone (Nbz) derivative, also termed an N-acylurea, in the presence of base. This species is susceptible to subsequent thiolysis to generate the final C-terminal peptide thioester either prior to purification or in situ under ligation conditions. This approach uses commercially available derivatives and simple, on-bead reaction conditions, such that it minimizes post-cleavage workup procedures; in fact, the resin has recently become commercially available as “Dawson Dbz AM resin”. It has been exploited successfully in the preparation of several proteins. [6]

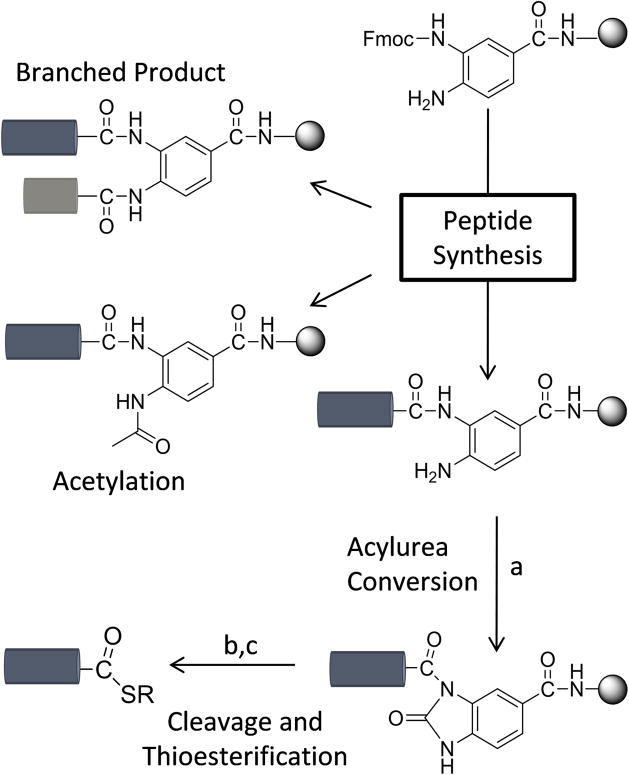

Scheme 1.

Synthetic scheme for thioester generation using 3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Dbz) as a masked thioester during Fmoc-SPPS. a) Treatment of the single peptide product with p-nitrophenyl chloroformate followed by DIEA yields the Nbz derivative. b) TFA cleavage and c) thioester conversion generate the peptide thioester. Over-acylation during peptide synthesis results in branched and acetylated products that reduce overall yield.

Here, we demonstrate that in the context of Gly-rich sequences or in the preparation of long, challenging peptides, acylation of the second Dbz amine leads to the accumulation of branched and acetylated peptide products over the course of a typical synthesis. We demonstrate that reversible allyloxycarbonyl (Alloc) protection of the unreacted amine eliminates extraneous acylation. Reversible protection of the Dbz linker allows the use of optimized coupling conditions and acetylation capping steps without concern for over-acylation and product loss, and is compatible with automated preparation of peptide thioesters. We introduce a protected Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) base resin that may be used directly with most amino acids commonly exploited as ligation junctions.[7] We use this resin to prepare two peptide thioesters derived from Gly-rich regions of histone H4 and a 44-residue peptide used in the total synthesis of histone H3.[8]

Results and Discussion

Unprotected Dbz linker is susceptible to over-acylation during peptide synthesis of Gly-rich sequences

Our laboratory is interested in the synthesis of peptide thioesters for the preparation of modified histone proteins by chemical ligation.[9] In this context, we synthesized peptide H4C derived from the C-terminus of histone H4 and peptide H4N derived from the N-terminal tail of histone H4 (Table 1) using the Dbz linker and standard Fmoc-SPPS protocols with HBTU activation.

Table 1.

Peptide Sequences

| Peptide | Sequence [a] |

|---|---|

| H4C | GRTLYGFGG |

| H4N | SGRGKGGKGLGKGG |

| H3M | (Thz)LREIRRYQ(Kac)STELLIRKLPFQRLVREIAQDFKTDLRFQSSAV-(Nle) |

Thz: Thiazolidine; Nle: Norleucine

Cleavage from the resin and analysis of the products by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS revealed not only the desired products but also a range of products that were larger than the desired species (Fig. 1A; for full product list and H4N analysis see Supplemental Information). We attribute these products to extraneous acylation of the Dbz during coupling cycles in chain extension, leading to the incorporation of a second peptide chain initiating at several points along the peptide sequence. We denote these peptides by the point of branching, numbering the peptide sequence from the C-terminus. Products included a significant amount of the product with two peptide chains such as H4C-C1 [GRTLYGFGG-Dbz(GRTLYGFGG)], corresponding to the complete coupling of the C-terminal Gly at each Dbz amine followed by full chain extension. A ladder of additional species were also observed originating at each Gly in the sequence, suggesting that non-productive acylation of the second amine was not limited to initial resin loading. Interestingly, the minor product H4C-C3 corresponds to two chains with the absence of two Gly, most likely H4C-C3 [GRTLYGFGG-Dbz(GRTLYGF)]; this suggests over-acylation is not limited to glycine. [10]

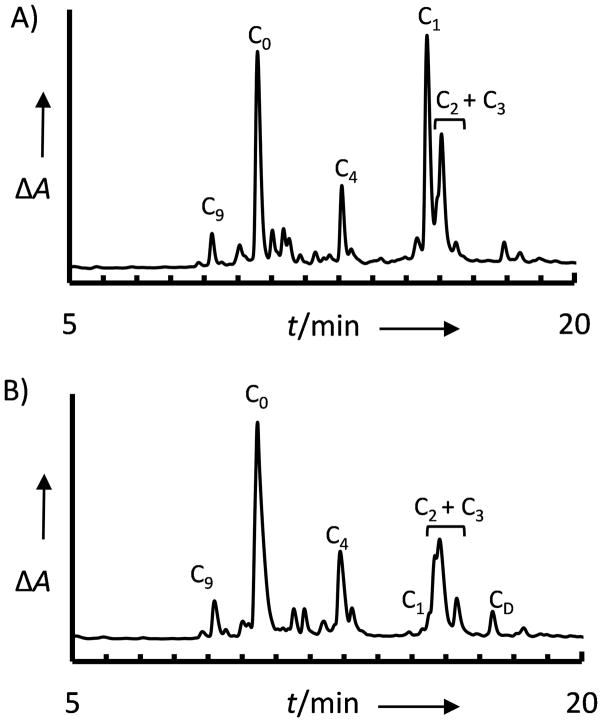

Figure 1.

RP-HPLC chromatogram (14–50% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA gradient) of C-terminal-Dbz H4 peptide without Alloc protection. C-terminal AA introduced as A) Fmoc-Gly-OH and B) Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly-OH. Peptide identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS analysis; for full product analysis see Supplemental Table T1. Desired product H4C-C0 : [M+H]+ observed m/z 1060.4, expected m/z 1060.5; Major branched product H4C-C1 : [M+H]+ observed m/z 1969.1, expected m/z 1969.0.

When a single amine of Dbz is acylated, the unreacted amine should be deactivated by a combination of steric and electronic factors.[5] This deactivation has been reported to be sufficient to minimize acylation at the second amine during chain extension, although extraneous acetylation during capping steps has been reported by multiple researchers and some over-acylation has been observed during coupling cycles. [10–11] Peptides H4C and H4N are extremely glycine-rich, and each has a C-terminal Gly-Gly sequence. These sequences present a particular challenge to the combination of steric and electronic factors that modulate reactivity at the second amine of Dbz during chain extension.

Since Gly is small and flexible, we speculated that the C-terminal Gly residue might provide minimal steric exclusion to coupling at the second amine of Dbz. We therefore incorporated the C-terminal Gly as the Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly derivative, introducing additional steric bulk via the dimethoxybenzyl-protected amine. RP-HPLC analysis of the synthesis products revealed a significant reduction in the fully branched product H4C-C1 (Fig. 1B). This suggests that incorporation of Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly at a single Dbz amine prevented extraneous acylation by the bulky Gly derivative. However, each subsequent Gly in the sequence was incorporated as the inexpensive Fmoc-Gly-OH, and synthesis products included the ladder of products that corresponded to branching at positions throughout the sequence. While Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly-OH was thus suitable for on-resin incorporation of a single Gly at the C-terminus, the increased steric bulk could not prevent the formation of subsequent nonproductive side products.

Exploring the parameters of over-acylation

Our initial syntheses were carried out on Rink-MBHA resin. In order to eliminate the possibility that resin effects alone might modulate reactivity to account for the discrepancy between our results and other reports,[11] syntheses of the H4C and H4N peptides were carried out on Rink substituted ChemMatrix and PAL-PEG-PS resins respectively; branched products were still generated (Supplemental Figure S2). These results suggest that resin effects can modulate but not eliminate reactivity of the second Dbz amine under peptide synthesis conditions.

There are several alternative synthetic strategies that could be pursued to prepare the H4C and H4N peptide thioesters, particularly given that the Gly terminus is not subject to racemization.[4] To determine if overacylation was specific to our sequences, we further investigated the influence of the C-terminal amino acid. We synthesized peptides Boc-LYRAGA and Boc-LYRAGF, each containing a single Gly residue, on Dbz-Arg Rink MBHA resin, using a single 30 minute HCTU coupling cycle with 1.5 eq diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) for the LYRAG sequence. After full chain extension, we carried out a single capping step using a common acetylation cocktail for manual SPPS.[12]

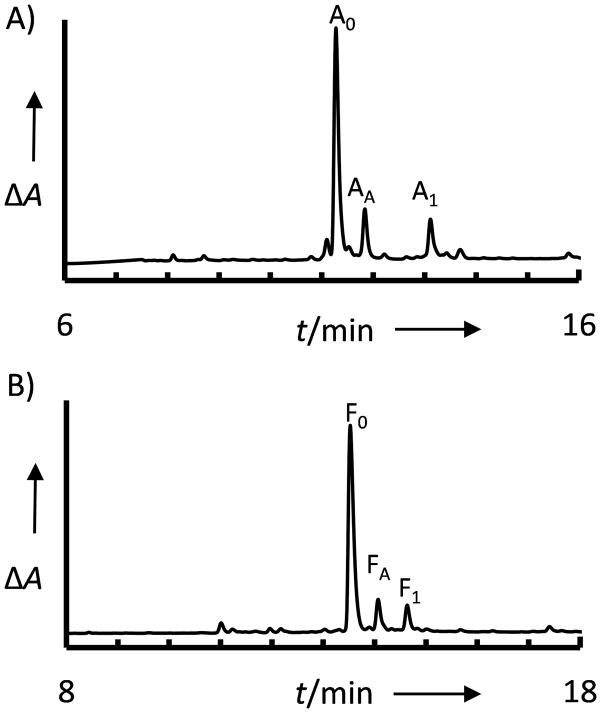

Three primary products were observed for each synthesis (Fig. 2): the desired species, addition of a second chain by acylation during Gly coupling (A1: 9%; F1: 6% by integration of RP-HPLC chromatogram) and the acetylated species (AA: 12%; FA 7%). It should be noted that optimized capping conditions have been reported to minimize acetylation at the unprotected Dbz amine [11] in comparison to standard capping cocktails. However, even minimal non-productive acetylation product would accumulate at each step of a long peptide synthesis. Further, the over-acylation observed during the glycine coupling cycles demonstrates that while the flexible Gly-Gly terminus likely exacerbated the extent of over-acylation in the context of peptides H4C and H4N, these side reactions also occur with bulkier side chains on the C-terminal residue.

Figure 2.

RP-HPLC chromatogram of crude cleavage mixture for peptides A) LYRAGA-Dbz-Arg and B) LYRAGF-Dbz-Arg following synthesis and a single acetylation step (0–65% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA over 30 minutes). Peptide identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (Supplemental Figure S3)

Alloc protection for Dbz

Nonproductive side reactions might be expected given the carefully tuned reactivity required of Dbz in the N-acylurea strategy. Optimal product yield requires that only one amine per Dbz be derivatized by coupling of the first amino acid. Neither amine of the Dbz is inherently deactivated to acylation; a mixture of 3′ and 4′ acylated Dbz is produced when the C-terminal amino acid is coupled directly to fully deprotected Dbz.[5] This suggests that deactivation is dominated by the effect of acylation by the growing peptide chain. The remaining unreacted Dbz amine must remain sufficiently activated for reaction with the chloroformate required for conversion to Nbz following synthesis, while remaining fully inert to acylation during normal chain extension. In our hands, the deactivation or hindrance of the unreacted amine by a single peptide chain is insufficient to prevent acylation during Gly coupling cycles or capping under conditions required for the synthesis of long peptides.

Ideal, then, would be a Dbz resin in which the second amine would be reversibly protected to prevent undesired side reactivity during SPPS, but a single resin preparation might be used for peptides with different C-terminal amino acids. We chose to introduce allyloxy-carbonyl (Alloc) protection[13] for a single Dbz amine (Scheme 2). The Alloc group has a small steric profile and can be installed by reaction with an excess of allylchloroformate, parallel to the reaction with p-nitrobenzyl-chloroformate in the Nbz conversion.[5] Further, Alloc deprotection is compatible with most post-translational modifications and orthogonal to the thiazolidine protection [14] common in sequential native chemical ligation.

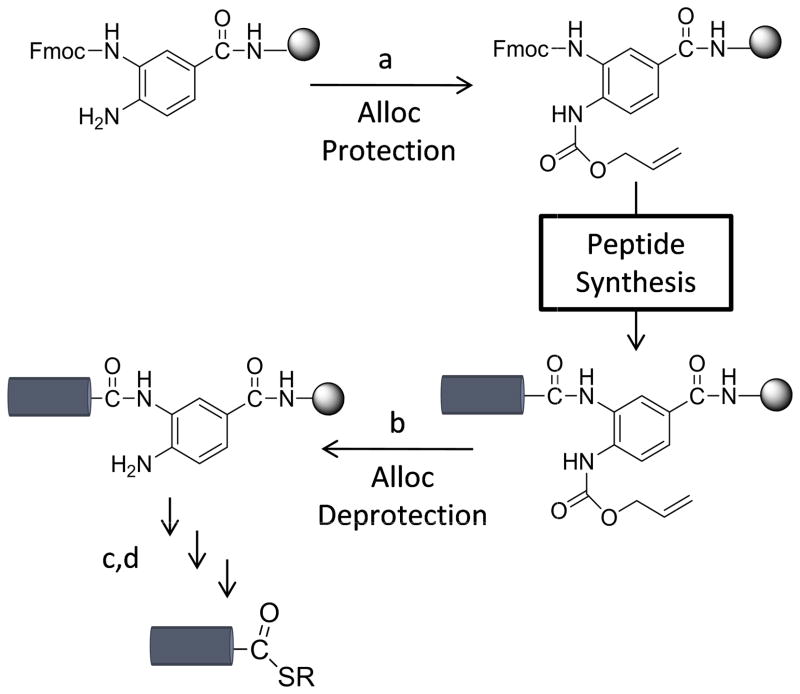

Scheme 2.

Dbz protection strategy. a) mono-Fmoc-Dbz is treated with allylchloroformate to generate the Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) resin. Peptide synthesis introduces a single peptide chain. b) Treatment with phenylsilane and tetrakis(triphenyl-phosphine)-palladium(0) regenerates the peptide-Dbz conjugate on resin, which may be c) converted to Nbz and d) cleaved from resin as in Scheme 1 to prepare the peptide thioester.

Mono-3′-Fmoc-Dbz-OH was prepared via modified literature procedures[5] and coupled to Arg-Rink MBHA LL resin. The resin was treated with excess allylchloroformate in the presence of DIEA to generate Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc)-Arg Rink-MBHA resin. Arg was included in initial syntheses to simplify the RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS analysis of small peptide products. No significant differences were observed for syntheses carried out with single amino acid Arg or Leu spacers, or with Dbz coupled directly to Rink linker. Treatment with 20% piperidine then afforded a single Dbz amine for reaction. Notably, since a single isomer, 3′-Fmoc-Dbz-OH, dominated under our conditions, the downstream purification of the peptide derivative is simplified relative to the multiple isomers typically reported for on-resin coupling of amino acid to Dbz resin.[5]

Preparation of Fmoc-AA-Dbz(Alloc) Resins

In the context of mixed 3′ and 4′ peptide-coupled Dbz resin, whichever amine remains uncoupled is typically rendered less active towards acylation. Alloc protection of mono-Fmoc-Dbz resin followed by removal of the Fmoc group would generate mono-Alloc-Dbz resin leaving the more reactive 3′ amine for growth of the peptide chain. However, the coupled Alloc group would be anticipated to reduce the reactivity of the remaining amine. The ability to couple amino acids to this protected Dbz linker was therefore a significant unknown.

We tested the loading of 15 naturally occurring amino acids and norleucine (Nle), which is commonly substituted for Met in synthetic proteins, onto Dbz(Alloc)-Arg resin. Double coupling using HATU activation with 15-fold molar excess of amino acid provided complete loading for the majority of amino acids (Table 2) with the exception of β-branched hydrophobic amino acids Ile and Val; notably, βbranched Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH did couple completely. For many amino acids the conditions used for the library are excessive; complete loading of Fmoc-Norleucine-OH and Fmoc-Ala-OH were carried out using a single coupling cycle and 10–15 equivalents of amino acid (data not shown). However, we have not explored the minimal coupling requirements for each amino acid, and the conditions described above are suitable for quantitative amino acid loading without requiring cleavage tests to assess completion. The Dbz(Alloc) base resin is thus compatible with the amino acids most commonly used as C-terminal amino acids in chemical ligation. Further, the HATU coupling cycles are programmable on an automated synthesizer such as the Aapptec Apex 396 used here, and different C-terminal amino acids may be loaded in parallel using this approach.

Table 2.

Loading of C-terminal Fmoc protected amino acid on Dbz(Alloc)-Arg resin

| Amino Acid | % Loading[a] |

|---|---|

| Alanine | >95 % |

| Arginine (Pbf) | >95 % |

| Glutamic Acid (OtBu) | >95 % |

| Glycine | >95 % |

| Histidine (Trt) | >95 % |

| Isoleucine | 33 % |

| Leucine | >95 % |

| Lysine (Boc) | >95 % |

| Norleucine | >95 % |

| Phenylalanine | >95 % |

| Serine (tBu) | >95 % |

| Threonine (tBu) | >95 % |

| Tryptophan (Boc) | >95 % |

| Tyrosine (tBu) | >95 % |

| Valine | 47 % |

| Valine[b] | >95 %[b] |

Percent loading determined by integration of RP-HPLC chromatograms (Supplemental Figure S5,S6). Coupling was carried out with 15-fold excess amino acid and HATU activation for 2 × 1 hour.

Fmoc-Val-Dbz-Arg resin was subsequently protected to generate Fmoc-Val-Dbz(Alloc)-Arg

Ile and Val require highly activating conditions for complete single acylation on unprotected Dbz, and demonstrate incomplete loading on Dbz(Alloc) protected resin. For these residues, the pre-coupled Fmoc-AA-Dbz resin may subsequently be protected to generate the Fmoc-AA-Dbz(Alloc) resin (Supplemental Scheme S1). While this approach is theoretically compatible with any amino acid, it does require additional time-consuming resin handling steps such that the Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) base resin is more convenient for practical use where appropriate.

Synthesis of Gly-rich sequences on protected Dbz(Alloc) resin

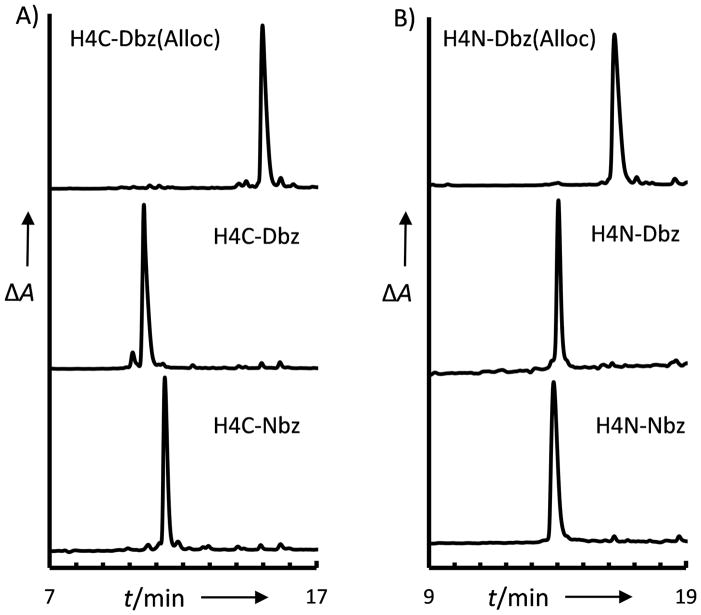

The glycine-rich H4C and H4N peptides were synthesized on Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) base resin. HATU activation was used for coupling of the C-terminal Gly, HCTU activation was used throughout the sequence, and acetylation/capping steps were carried out after each coupling cycle. Cleavage and analysis prior to Alloc deprotection afforded a single primary product that corresponds to the desired species (Figure 3, top). Alloc deprotection[15] (Fig. 3, middle) and subsequent conversion to the Nbz derivative (Fig. 3, bottom) were carried out. In each case the desired product was the single primary species observed. Quantitative cleavage of the H4C-Nbz resin after deprotection and conversion to the N-acylurea species provided a 94% crude yield, of which 83% was the desired product by RP-HPLC integration. In comparison to the syntheses on unprotected Dbz resin illustrated in Figure 1, this represents a significant improvement in the yield of the desired product.

Figure 3.

RP-HPLC analyses of peptides synthesized on Dbz(Alloc) resin (14–50 % acetonitrile/0.1 % TFA over 30 minutes): A) H4C derivatives. top: H4C-Dbz(Alloc)-NH2 middle: H4C-Dbz-NH2 bottom: H4C-Nbz-NH2 B) Fmoc-H4N derivatives, top: Fmoc-H4N-Dbz(Alloc)-NH2 middle: Fmoc-H4N-Dbz-NH2 bottom: Fmoc-H4N-Nbz-NH2. Peptide identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (see Supplemental Figure S7)

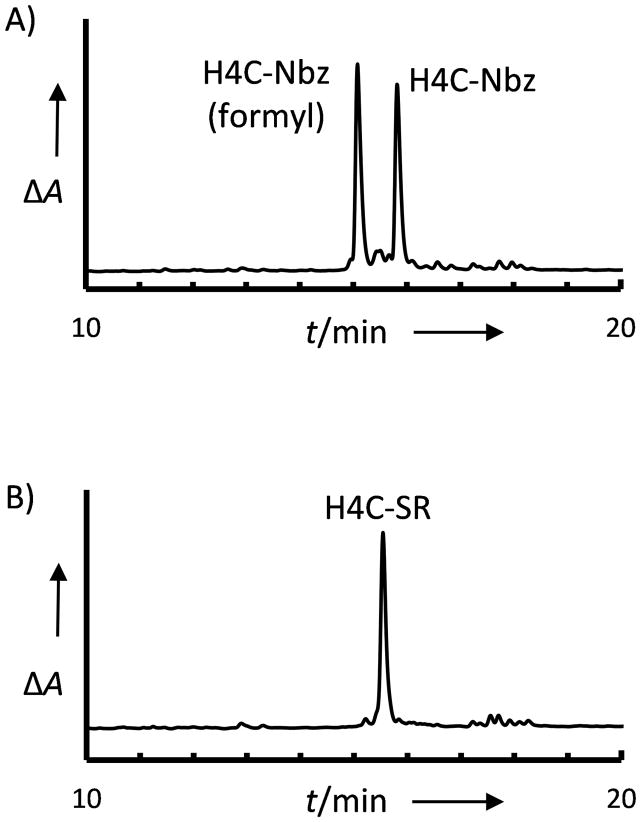

One advantage of the Nbz approach to thioester preparation is compatibility with automated peptide synthesis and the reduction of manual resin handling steps. Alloc deprotection[16] and Nbz conversion were therefore carried out using programmed cycles (Figure 4). In addition to the desired Nbz derivative, an additional product was observed with a mass that corresponds to +28 Da (Fig. 4A). After treatment with sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA) to generate the thioester derivative, both peaks converged to the desired thioester product (Fig. 4B). We attribute the additional product to contamination of the p-nitrobenzylchloroformate solution with DMF during syringe-driven reagent delivery on the Apex 396 instrument, which would generate the formylated product as described by Brik and coworkers.[17] These results suggest that Alloc deprotection and Nbz conversion may be automated to assist in the parallel synthesis of peptide libraries, but that care must be taken in designing synthesis procedures in order to avoid complicated peptide purification procedures. One alternative might be carrying out the Nbz conversion entirely in DMF, which has been reported to generate only the formylated derivative.[17] Alternately, both Nbz derivatives might be converted to thioester form prior to purification. In each case, purification of only a single product peak would be required.

Figure 4.

Deprotection and Nbz conversion can be carried out using automated protocols. A) RP-HPLC analysis of the cleavage products resulting from Nbz conversion using automated cycles on an Apex 396 synthesizer. Two products are observed: H4C-Nbz(formyl) [M+H]+ observed m/z 1114.8, expected m/z 1114.5; H4C-Nbz, [M+H]+ observed 1086.2, m/z, expected 1086.5 m/z. B) RP-HPLC analysis after thiolysis with MESNA to generate the H4C thioester: [M+H]+ observed 1051.0 m/z, expected 1051.4 m/z.

Synthesis of a 44-residue histone-derived thioester

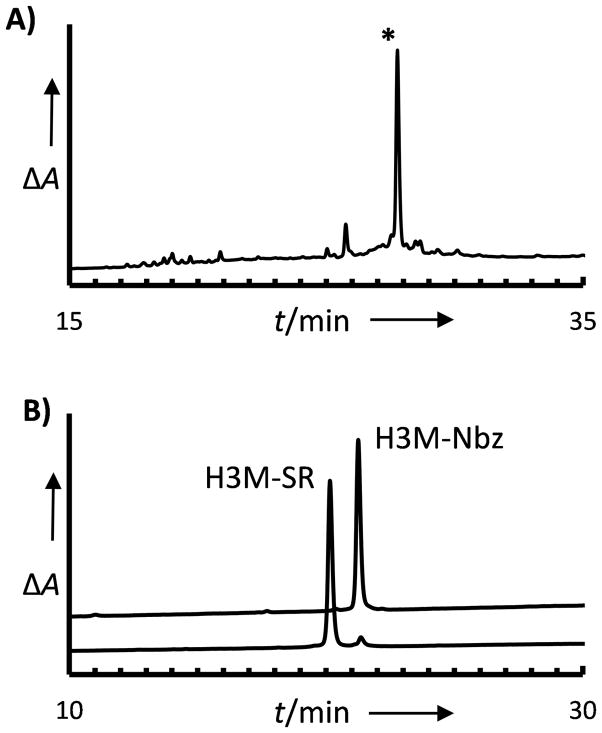

In order to assess our protection strategy in the context of a challenging peptide sequence, we synthesized a 44-residue peptide derived from the sequence of histone H3. Peptide H3M corresponds to residues 47 to 90 of histone H3 acetylated at Lys56. It is used in the total synthesis of modified histone H3 by sequential native chemical ligation.[8] Synthesis of this peptide on protected Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) resin allowed the use of optimized HCTU activation, double coupling cycles over the majority of the sequence, and acetylation capping steps to eliminate deletion products to simplify purification. After removal of the Alloc protecting group a small aliquot of resin was cleaved; one primary product was observed, corresponding to 55% of total product by RP-HPLC integration (Figure 5A). The remainder of the resin was converted to the Nbz form; quantitative cleavage of H3M-Nbz from the resin resulted in 60% crude peptide yield. Purified H3M-Nbz was further converted to the active MESNA thioester form, H3M-SR (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

44-residue H3M peptide synthesized using protected Dbz(Alloc) linker. A) RP-HPLC analysis of H3M-Dbz after removal of Alloc (18–66% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA over 33 minutes); * indicates desired product. B) RP-HPLC analysis of purified H3M-Nbz before (top) and after (bottom) conversion to the H3M-MESNA thioester (32–59% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA over 30 minutes). Peptide identities were confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (see Supplemental Figure S9).

Conclusions

The N-acylurea approach for the preparation of peptide thioesters by Fmoc-SPPS is hampered by the reactivity of an unprotected amine on the Dbz linker that is susceptible to acylation during chain extension and capping steps. Since this reactive amine is required for conversion of Dbz to the active Nbz species, the potential for spurious acylation is inherent in the N-acylurea approach. We present a reversible Alloc protection strategy for the Dbz linker that eliminates extraneous acylation during chain extension, and develop a protected base resin that is compatible with common native chemical ligation junctions. We demonstrate that the use of this protection strategy significantly improves the synthesis of peptide thioesters.

Careful selection of reaction conditions with mild activating conditions and minimal DIEA could potentially reduce branched side products in the context of the unprotected Dbz linker, particularly in the routine synthesis of relatively short peptide sequences. However, even minimal side products accumulate over the course of the syntheses of long peptide sequences. Furthermore, for the synthesis of challenging peptide sequences it is important to retain all available synthetic tools rather than restriction to a subset of reagents or reaction conditions selected to be less active. Protection of the Dbz amine allows the use of optimized coupling conditions and capping cycles, and therefore improves the synthesis of peptide thioesters by Fmoc-SPPS.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

All solvents and reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. Methanol, anhydrous diethyl ether, hexanes and dichloromethane (DCM) were obtained from Fisher. N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) were purchased from AGTC Bioproducts. Triisopropylsilane (TIS) was purchased from GFS Chemicals. Acetonitrile (ACN), 3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Dbz), N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), piperidine, allylchloroformate, phenylsilane and tetrakis(triphenyl-phosphine)-palladium(0) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Di-Fmoc-3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (Di-Fmoc-Dbz) was purchased from Anaspec. 2-(7-Aza-1-H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium hexafluorophosphate (HATU), 2-(6-Chloro-1-H-benzotriazol-1-yl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluoro-phosphate (HCTU), 2-(1-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), 6-chloro-1-hydroxybenzotriazole (6-Cl-HOBt) and all protected amino acids except where noted were purchased from Aapptec. Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was purchased from Halocarbon. Fmoc-Rink amide MBHA LL resin (0.36 mmol/g), Fmoc-Rink linker, Boc-Gly-OH, Boc-Leu-OH·H2O, Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly-OH, Fmoc- Nle-OH, Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-Thr(ΨMe,Mepro)-OH, and Fmoc-OSu were obtained from Novabiochem. Chem Matrix resin was obtained from Matrix Innovation. Fmoc-PAL-PEG-PS resin was obtained from Applied Biosytems.

Peptide Synthesis

Peptides were synthesized on an Apex 396 automated peptide synthesizer (Aapptec) except as otherwise noted. Deprotec-tion was carried out by treatment with 20% piperidine in NMP. Mono-Fmoc-Dbz-OH (1.1 eq.) or di-Fmoc-Dbz-OH (2.2 eq.) was coupled to resin and further synthesis occurred as described... Peptides were cleaved from resin by treatment for 2.5 hours (95% TFA/2.5% H2O/2.5% TIS), followed by precipitation and washing with cold diethyl ether.

Synthesis of H4N and H4C peptides on unprotected Dbz resin

Peptides H4N-Dbz and H4C-Dbz were synthesized on Fmoc-Rink amide MBHA LL resin. Where noted, C-terminal Fmoc-(Dmb)Gly-OH (2.2 eq.) was manually coupled onto deprotected Dbz with HBTU activation; all other amino acids were coupled 2 × 45 minutes (6 eq. of 1 AA/0.9 HBTU/1.8 DIEA). All non-terminal glycine residues were introduced as the Fmoc-Gly-OH derivative. For peptide H4C, N-terminal Gly was introduced as Boc-Gly-OH. For peptide H4N, N-terminal Ser was introduced as Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-OH to allow potential acetylation of the peptide N-terminus. Product identities were confirmed by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS (see Supplemental Figure S1 and Supplemental Tables S1-S2)

Synthesis of LYRAGA and LYRAGF peptides

To simplify analysis by generating only one Dbz isomer, the first amino acid was coupled to protected 4′-Alloc-Dbz-Arg MBHA LL resin for 2 × 1 hour (15 eq. of 1 AA/0.9 HATU/1.8 DIEA). The Alloc group was removed, revealing the 4′ amine throughout the remainder of the synthesis. Subsequent amino acids were coupled for 30 minutes (6 eq. of 1 AA/0.9 HCTU/1.5 DIEA). Leu was introduced as Boc-Leu-OH. After synthesis was complete, a single 5 minute capping cycle was carried out (15% acetic anhydride/15% DIEA/70% DMF, in excess).[12]

Synthesis of mono-Fmoc-Dbz-OH

3,4-diaminobenzoic acid (1 g, 6.5 mmol) was resuspended in CH3CN/NaHCO3 (1 : 1, 125 mL) and reaction was initiated with the dropwise addition of Fmoc-OSu (2.4 g, 7.1 mmol) in CH3CN/NaHCO3 (1 : 1, 15mL) and proceeded for 2 hours. HCl was added to a final pH of 1.0 and filtered. Filtrate was dissolved in DMSO (4 mL), precipitated with acidified reaction buffer, washed extensively, and dried under vacuum to yield a light gray product (1.0 g, 41% yield). Product identity and purity was validated with NMR (see Supplemental Information).

Preparation of Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) resin

mono-Fmoc-Dbz-OH (1.1 eq.) was coupled to resin for 2 hours (1 eq. HBTU/2 eq. DIEA). The resin was washed with DMF and DCM. Allylchloroformate (350 mM) and DIEA (1 eq. to resin loading) in anhydrous DCM were added and reaction proceeded with nutation (24 hours at 25 °C). For resin prepared with C-terminal Arg, reaction progress was monitored by analytical cleavage of resin followed by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS.

Synthesis of H4N and H4C peptides on Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc) resin

C-terminal Fmoc-Gly-OH residue (15 eq.) was activated with HATU (1 AA: 0.9 HATU : 1.8 DIEA) and coupled to Dbz(Alloc) derived Rink amide MBHA LL resin with 2 × 1 hour couplings. Subsequent residues were introduced with HCTU (H4C) or HBTU (H4N) protocols. For peptide H4C, N-terminal Gly was introduced as Boc-Gly-OH.

Determination of amino acid loading on Dbz(Alloc) resin

Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc)-Arg derived Rink amide MBHA LL resin was prepared as described. Identity and purity of the desired Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc)-Arg species was determined to be >95% by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF analysis ([M+H]+ Observed: 614.1 m/z; Expected 614.2 m/z).Following Fmoc deprotection with 20% piperidine/NMP, amino acids (Fmoc-Ala-OH, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-Glu(tBoc)-OH, Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Ile-OH, Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Lys(tBoc)-OH, Fmoc-Nle-OH, Fmoc-Phe-OH, Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Trp(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Tyr(tBu)-OH and Fmoc-Val-OH) were introduced with 2 × 1hr coupling using amino acid (15 eq.) activated with HATU/DIEA. Peptides were cleaved from resin and products were resolved by RP-HPLC on a Grace Vydac C18 column (0–45 % acetonitrile/H2O/0.1% TFA over 30 minutes). Coupling efficiency was determined by integration of the obtained RP-HPLC chromatogram at 218 nm (see supplemental information). Product identity was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS.

Synthesis of H3M-Dbz(Alloc) peptide

Boc-Thiazolidine-LREIRRYQKacSTELLIRKLPFQRLVREIAQDFKTDLRFQSSAV-Nle-Dbz(Alloc)-Leu-CONH2) was synthesized on Fmoc-Dbz(Alloc)-Leu MBHA Rink Amide LL resin. The first amino acid, Fmoc-Nle-OH, was introduced manually (10 eq. of 1 AA/0.9 HBTU/1.5 DIEA) for 2 hours but was determined to be complete after one hour by test cleavage. Automated synthesis was carried out using HCTU activation and capping, with double coupling for residues known to be in synthetically challenging regions (underlined in sequence). S57-T58 were introduced as the pseudoproline dipeptide Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-Thr(ΨMe,Mepro)-OH (2.2 eq. over resin loading). Peptide identity and purity were confirmed using RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure S9).

Alloc deprotection

Alloc protected resin was swollen in DCM and briefly sparged with Ar. Deprotection was initiated with the addition of PhSiH3 (20 eq.)and Pd(PPh3)4 (0.35 eq.) and the reaction proceeded for 20–30 min at 25 °C with nutation (manual cycles) or with automated mixing (on Apex synthesizer). The deprotection cycle was repeated as needed. [15–16]

Peptide-Nbz conversion

Nbz conversion was performed according to literature methods.[5] For manual cycles, resins to be converted were swollen in DCM and treated with p-nitrophenylchloroformate (p-NPC, 5 eq.) for 45 minutes at 25 °C. Resin was washed with DCM, converted to DMF and subsequently nutated for 15 minutes with DIEA (0.5 M in DMF). For automation on an Apex 396 synthesizer, conversion was carried out on a 0.05 mmol scale. Two separate solutions of p-nitrophenylchloroformate (0.25 M in DCM)and DIEA (0.5 M in DMF) were prepared. Resin was washed with DCM and p-NPC solution (1 mL, 5 eq.) was added and mixed for 45 minutes. The resin was washed with DCM and then DMF. DIEA solution (1 mL) was added, the resin was mixed for 15 minutes, and subsequently washed with DMF and DCM.

Thioester generation

Lyophilized H4C and H4N Nbz peptides were resuspended in buffer (200 mM phosphate, pH 7.5) with sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate (50 mM). Conversion to thioester was monitored by RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS until complete (typically 1 hour). Lyophilized H3M-Nbz was resuspended in buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 6 M guanidine, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM MESNA); conversion was complete in 3 hours.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Riuxuan (Ryan) Yu and Sarah Dreher provided assistance with peptide characterization. This work was supported by a NSF CAREER award (MCB-0845696) and the National Institutes of Health (GM083055).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Kent SBH. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:338–351. doi: 10.1039/b700141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Flavell RR, Muir TW. Accounts Chem Res. 2009;42:107–116. doi: 10.1021/ar800129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Berrade L, Camarero JA. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3909–3922. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Ottesen JJ, Bar-Dagan M, Giovani B, Muir TW. Biopolymers. 2008;90:406–414. doi: 10.1002/bip.20810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Camarero JA, Adeva A, Muir TW. Lett Pept Sci. 2000;7:17–21. [Google Scholar]; b) Bang D, Pentelute BL, Gates ZP, Kent SB. Org Lett. 2006;8:1049–1052. doi: 10.1021/ol052811j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Clippingdale AB, Barrow CJ, Wade JD. J Pept Sci. 2000;6:225–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1387(200005)6:5<225::AID-PSC244>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Futaki S, Sogawa K, Maruyama J, Asahara T, Niwa M, Hojo H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:6237–6240. [Google Scholar]; c) Backes BJ, Ellman JA. J Org Chem. 1999;64:2322–2330. doi: 10.1021/jo990271w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Ingenito R, Bianchi E, Fattori D, Pessi A. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11369–11374. [Google Scholar]; e) Shin Y, Winans KA, Backes BJ, Kent SBH, Ellman JA, Bertozzi CR. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11684–11689. [Google Scholar]; f) Warren JD, Miller JS, Keding SJ, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6576–6578. doi: 10.1021/ja0491836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Botti P, Villain M, Manganiello S, Gaertner H. Org Lett. 2004;6:4861–4864. doi: 10.1021/ol0481028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Kawakami T, Sumida M, Nakamura K, Vorherr T, Aimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:8805–8807. [Google Scholar]; i) Mende F, Seitz O. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2007;46:4577–4580. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Camarero JA, Hackel BJ, de Yoreo JJ, Mitchell AR. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4145–4151. doi: 10.1021/jo040140h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mende F, Seitz O. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2011;50:1232–1240. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco-Canosa JB, Dawson PE. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2008;47:6851–6855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Chiang KP, Jensen MS, McGinty RK, Muir TW. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2182–2187. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pentelute BL, Barker AP, Janowiak BE, Kent SBH, Collier RJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:359–364. doi: 10.1021/cb100003r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kumar KSA, Spasser L, Erlich LA, Bavikar SN, Brik A. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2010;49:9126–9131. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackeng TM, Griffin JH, Dawson PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10068–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimko JC, North JA, Bruns AN, Poirier MG, Ottesen JJ. J Mol Biol. 2011;408:187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Manohar M, Mooney AM, North JA, Nakkula RJ, Picking JW, Edon A, Fishel R, Poirier MG, Ottesen JJ. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23312–23321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) North JA, Javaid S, Ferdinand MB, Chatterjee N, Picking JW, Shoffner M, Nakkula RJ, Bartholomew B, Ottesen JJ, Fishel R, Poirier MG. Nuc Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White PD, Behrendt R. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiefenbrunn TK, Blanco-Canosa J, Dawson PE. Biopolymers. 2010;94:405–413. doi: 10.1002/bip.21486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camarero JA, Muir TW. Curr Protocols in Protein Sci. Vol. 15. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1999. pp. 18.14.11–18.14.23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Stevens CM, Watanabe R. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:725–727. [Google Scholar]; b) Guibe F. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:2967–3042. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Villain M, Vizzavona J, Rose K. Chem Biol. 2001;8:673–679. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bang D, Kent SBH. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2004;43:2534–2538. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dessolin M, Guillerez MG, Thieriet N, Guibe F, Loffet A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5741–5744. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grieco P, Gitu PM, Hruby VJ. J Pept Res. 2001;57:250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2001.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siman P, Blatt O, Moyal T, Danieli T, Lebendiker M, Lashuel HA, Friedler A, Brik A. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1097–1104. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.