Abstract

Aims

Cost burdens represent a significant barrier to medication adherence among chronically ill patients, yet financial pressures may be mitigated by clinical or organizational factors, such as treatment aligned with the Chronic Care Model (CCM). This study examines how perceptions of chronic illness care attenuate the relationship between adherence and cost burden.

Methods

Surveys were administered to patients at 40 small community-based primary care practices. Medication adherence was assessed using the 4-item Morisky Scale, while five cost-related items documented recent pharmacy restrictions. CCM experiences were assessed via the 20-item Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Nested random effects models determined if chronic care perceptions modified the association between medication adherence and cost-related burden.

Results

Of 1,823 respondents reporting diabetes and other chronic diseases, one-quarter endorsed intrapersonal adherence barriers, while 23% restricted medication due of cost. Controlling for age and health status, the relationship between medication cost and CCM with adherence was significant; including PACIC scores attenuated cost-related problems patients with adequate or problematic adherence behavior.

Conclusions

Patients experiencing treatment more consistent with the CCM reported better adherence and lower cost-related burden. Fostering highly activated patients and shared clinical decision making may help alleviate medication cost pressures and improve adherence.

Keywords: diabetes, medication adherence, chronic care delivery, out-of-pocket cost

Introduction

Poor adherence to prescribed medications is a significant problem for patients with chronic illness. Most estimates suggest that only 50% of patients with diabetes or other conditions take their medication regularly [1–3]. Using electronic pharmacy records, a recent study found that 22% of patients with type 2 diabetes prescribed a new medication either never picked up the initial prescription or only filled it once [4]. Medication non-adherence contributes to deteriorating symptoms, worsens overall disease burden, and leads to unnecessary hospital admissions and higher health care costs [5].

Previous studies demonstrate that patient characteristics such as age, sex, race, and education are associated with medication adherence [1, 5]. In addition, financial burdens such as low income or socioeconomic status, lack of prescription drug coverage, and high out-of-pocket costs are also significant adherence barriers across a variety of physical and mental health conditions [6–8]. There is some evidence that non-economic factors may help mitigate the likelihood of reducing medication use in response to financial pressures [2, 6, 9, 10]. Piette and colleagues have proposed a conceptual framework to describe the influence of patient, medication, clinician, and health system factors on individuals’ responses to medication costs [2]. This framework suggests that cost-related medication non-adherence should be evaluated within a broader context that takes into account the role of organizational and social dimensions such as health system factors, patient self-efficacy and patient-provider communication.

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) describes a set of 6 clinical practice elements designed to optimize management of chronic illness – community linkages, organizational support, self-management support, delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information systems. The CCM was developed out of a perceived need to address the gap in evidence-based medicine regarding chronic illness care and effective clinical practice [11]. The goal of treatment aligned with CCM principles is to create “an informed, activated patient interacting with a prepared, proactive practice team, resulting in productive encounters and improved outcomes” [12]. Such activated patients can potentially overcome cost burdens and improve their medication adherence [2], as suggested by recent work in patients with both diabetes and bipolar disorder [13, 14].

Evidence to date suggests that interventions based on the CCM are associated with improved clinical outcomes in terms of quality of life, symptom reduction, and biological markers [15]. A few prior studies have examined whether specific features of the CCM, such as self-management support and improved patient-provider communication, are positively associated with medication adherence [14, 16–18]. However, limited evidence has addressed whether implementation of the CCM as a whole might positively influence medication adherence or the interaction with perceived medication cost barriers. To the best of our knowledge, no studies of the CCM have used medication adherence as a primary outcome. We hypothesized that the CCM targets and reflects several of the non-cost factors proposed by Piette et al. and therefore modify patients’ decisions regarding medication use due to perceived cost pressures. The purpose of this study is to determine whether receipt of services more consistent with the CCM is positively associated with better medication adherence among patients with chronic disease. Furthermore, we wished to examine whether experiences of better chronic illness care attenuated the relationship between medication adherence and cost burdens.

Methods

Setting and Subjects

This analysis uses baseline data obtained from a large cluster-randomized trial of practice implementation to improve treatment delivery via the CCM and diabetes outcomes in community clinics (for full study details, see Parchman et al., 2008 [19]). Beginning in 2007, forty small, autonomous, community-based primary care practices in South Texas were recruited to participate in this trial. These practices are representative of typical small primary care practices serving patients with type 2 diabetes, along with individuals with numerous other chronic diseases. Thirty of the clinics have only one physician, and of these thirty, eleven had one or more non-physician providers (either physician assistant or nurse practitioner). Ten clinics had two to four physicians and of those, five had at least one physician assistant or nurse practitioner. Prior to initiation, this study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Data Collection

As part of the baseline data collection, a minimum of 60 consecutive patients receiving care at each of the 40 clinics (age 18 or older) were asked to complete an anonymous survey during a primary care visits, regardless of known medical problem(s) or reason for their visit. A total of 2,634 patients were approached regarding participation, with 2,392 surveys completed, for a response rate of 90.8%. Solid representation was achieved across clinics, with the number of recruited patients ranging from 54 to 72. In order to limit the analysis to patients with one or more chronic illnesses, patients were asked to specify if they had a chronic health condition.

Measurements

For the primary outcome measure, patients were asked about perceived intrapersonal barriers to medication adherence using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), a four-item validated instrument regarding their medication use: 1) Have you ever stopped taking your medication because you were feeling better? 2) Have you ever stopped taking your medication because you were feeling worse? 3) Have you ever been careless about when you should take your medication? 4) Have you ever forgotten to take your medication? This instrument is commonly utilized for self-reported adherence in studies across chronic health conditions [20, 21]. For this study, each “yes” answer on the MMAS was assigned one point with higher overall values reflecting poorer adherence. Therefore, a total score of 0 was considered “Excellent,” 1 signified “Very good,” a 2 reflected “Good,” adherence, 3 indicated “Fair,” while 4 was represented “Poor.”

Cost-related adherence burden was assessed by a set of frequently used items developed by Piette and colleagues [7]. Patients were asked if, during the past 12 months, they had ever taken less of their medication than prescribed because of cost. If affirmative, individuals were then specifically asked if they engaged in any of the following restrictive or rationing behaviors: (1) taken fewer pills or a smaller dose, (2) not filled a prescription at all, (3) put off or postponed getting a prescription filled, (4) used herbal medication or vitamins when they felt sick rather than take their prescription medication, or (5) taken their medication less frequently than recommended to “stretch out” the time before getting a refill. Each of these five 1 – 5 point scaled responses ranged from “Never” to “At least once in the past week” for a totaled maximum score of 25, with higher values reflecting greater perceived cost burden.

The survey included the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC), a 20-question validated instrument designed by Glasgow et al. to assess patients’ perspectives of whether their care is consistent with the CCM [22, 23]. The PACIC is comprised of 5 subscales that represent key CCM components: patient activation, delivery systems, goal setting, problem-solving, and care-coordination. It asks patients to report how often their health care providers engage them in certain activities, such as talking about medication problems or providing them with a copy of their treatment plan. As acknowledged by its developers, the 5 PACIC subscales do not map perfectly onto the 6 elements of the CCM because some aspects of the model, such as clinical information systems and organizational support, are generally not visible to patients [23]. The PACIC has been compared to other surveys designed to measure patient experiences with integrated chronic care and has been found to be internally consistent and to demonstrate superior psychometric characteristics [23, 24]. PACIC scores were calculated in the same manner as the original validation study by Glasgow and colleagues [23]. Answers were scaled from 1–5, with responses ranging from a provider engaged the patient in that activity “none of the time” through “always.” Average PACIC values per patient were calculated across all 20 items, with higher average scores therefore reflecting better chronic care experiences.

Statistical analysis

Following a descriptive summary of patient characteristics for the study population, a one-way analysis of variance was conducted with 5 categories of cost-related medication adherence burden as described above to examine the relationship between medication adherence and perceived costs. The same analysis was done for the association between cost-related medication adherence and the PACIC score concerning patient perceptions of chronic care delivery. Next, three separate mixed or random-effects multivariable linear regression models were used to assess if the strength of the relationship between medication adherence and cost-related adherence burden changes when perceptions of the CCM were incorporated. All models controlled for self-reported patient age and health status, as measured by a single item overall health status question from the SF-36 (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor). The random effects models, with MMAS always as the dependent variable, were used to adjust for nesting or clustering of patients within clinic. Finally, an interaction effect at the patient level was examined by analyzing the mean values of both adherence and cost-related burden in patients with high PACIC scores (i.e., those reporting PACIC scores of ≥4, or that CCM elements were delivered at least “most of the time”) versus patients with low PACIC scores.

Results

O the 2,392 surveys collected, 76% (n=1,823) of respondents endorsed having one or more chronic diseases and all were included in this analysis. Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. Mean patient age was approximately 52 years (SD 16.7), with 65% females and 50% of Hispanic race/ethnicity, while nearly one-third completed some college. The average number of chronic diseases was 2.4 (SD 2.6). The majority of patients with chronic disease had excellent, very good, or good medication adherence (26%, 29%, and 25% respectively), with a mean MMAS score of 1.51 (SD 1.22, possible range 0 to 4); approximately 21% of patients reported fair or poor medication adherence. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of the study cohort acknowledged taking less of their prescribed medication due to cost, and the mean cost-related adherence burden score was 6.4 (SD 3.1, range 0 to 25). The average PACIC score of 3.05 (SD 1.19, range 1 to 5) reflects receipt of a moderate number of services and activities consistent with the CCM; this mean was slightly higher than the average score reported by respondents in Glasgow’s original PACIC validation study [23], but closely aligned with values obtained from subsequent primary care populations. [25, 26]

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of the Study Population (n=1,823)

| Variable | Mean (SD) or % | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 51.5 (16.7) | 18 – 95 |

| Female (%) | 65.2 | |

| Hispanic (%) | 50.2 | |

| Education completed (%) | ||

| Less than 8th grade | 7.9 | |

| Some high school | 9.6 | |

| High school/GED | 25.4 | |

| Some college | 30.7 | |

| College graduate or above | 26.4 | |

| Health status: good, very good, or excellent | 71.7% | |

| Number of chronic disease(s) | 2.4 (2.6) | 1 – 16 |

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale score | 1.51 (1.22) | 0 – 4 |

| Cost–related adherence burden score | 6.4 (3.1) | 0 – 25 |

| Average PACIC score | 3.05 (1.19) | 1 – 5 |

The bivariate association of medication adherence (Table 2) was significantly associated with both the PACIC scores (p<.001) and cost-related adherence burden (p=0.025). Patients reporting excellent adherence perceived a mean cost burden nearly half that of individuals with fair or poor adherence (6.2 vs. 10.1, p<.01). The relationship between PACIC score and MMAS was positive; that is, as PACIC scores increased, medication adherence improved. However, there was no association between cost-related adherence burden and PACIC. As a result, no formal test of mediation effect or attenuation of the relationship between cost-related adherence burden and the MMAS score was attempted.

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance: Self-Reported Medication Adherence and Cost-Related Adherence Burden, PACIC Score

| Medication adherence | Cost-burden, mean (SD) * | PACIC score, mean (SD) + |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 6.21 (2.38) | 3.18 (1.30) |

| Very good | 6.48 (2.59) | 3.07 (1.14) |

| Good | 7.78 (3.53) | 3.01 (1.17) |

| Fair | 8.91 (3.98) | 2.91 (1.13) |

| Poor | 10.08 (4.72) | 2.99 (1.16) |

F-test = 41.39, p<0.001

F-test = 2.80, p = 0.025

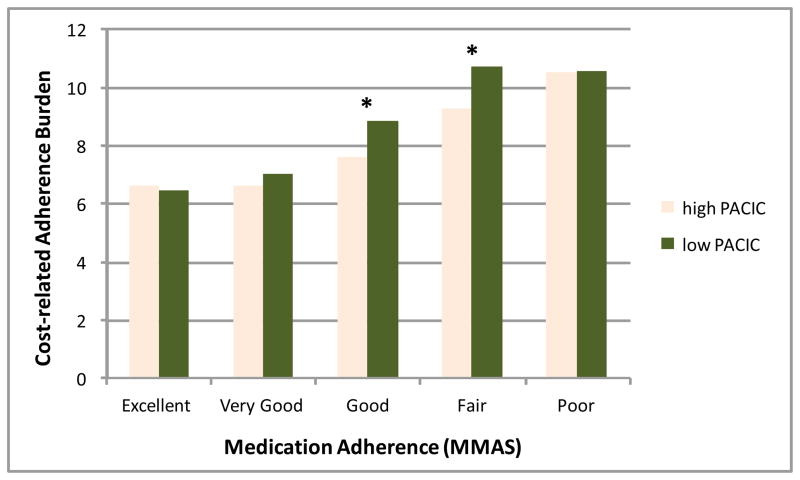

Turning to the multivariable regression models (Table 3), after controlling for age and health status, the first model presents a significant if modest relationship between higher medication cost burden and worse adherence per the MMAS (β = .28, p<.001). Likewise, model 2 with only PACIC included confirmed the minor inverse bivariate association with adherence (β = −.067, p=.003), or a slightly beneficial influence per the MMAS definition used here (higher score equals worse adherence). In Model 3 where both primary predictors were included, the strength of the relationship between cost-burden and adherence remained quite stable after incorporating perception of the CCM, suggesting an independent effect this new variable. The PACIC coefficient indicates patients perceiving care more consistent with CCM elements experience only a overall partial offsetting of the cost-burden effect. However, the interaction effect presented in Figure 1 indicates that patients reporting either good or fair medication adherence were considerably more sensitive to better chronic care delivery, as the high PACIC individuals in these two adherence groups experienced significantly fewer cost burdens (both p<.01), while patients endorsing other adherence levels with not affected by different PACIC scores.

Table 3.

Random Effect Models: Medication Adherence (MMAS), Cost-Related Burden and PACIC Score*

| Coefficient | t-test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Cost Burden on Medication Adherence | |||

| Cost Burden Score | 0.28 (se .024) | 11.99 | <.001 |

| Model 2: PACIC on Medication Adherence | |||

| PACIC | − .067 (se .023) | − 2.98 | 0.003 |

| Model 3: PACIC and CRAB on Medication Adherence | |||

| Cost Burden Score | 0.28 (se .025) | 11.06 | <.001 |

| PACIC Score | − .075 (se .025) | − 3.34 | .001 |

all models control for Age and Health Status

Figure 1.

Interaction Relationship between Medication Adherence and Cost-Related Burden among Patients with High and Low PACIC Scores

* p < .01

Discussion

In this study of patients with a chronic illness receiving cared in small primary care clinics, prescription costs and perceptions of care experiences were significantly associated with medication adherence. Overall, the relationship between cost burden and medication adherence was only slightly modified by the degree to which these chronic illness care was experienced. However, given the high prevalence of poor adherence among chronically ill individuals and intervention challenges, this finding is clinically important. This was especially true in the large group of patients struggling with medication behaviors, i.e., individuals reporting only fair to good adherence. In the current era of comparativeness effectiveness research that helps identify certain subgroups likely to experience additional advantages from a given intervention, the clinical implication of this finding suggests that patients who acknowledge borderline adherence behavior appear to benefit substantially more by care consistent with elements of the CCM. Clinical experience suggests that these individuals are often the patients that might potentially realize even greater benefits from enhanced chronic care delivery such as greater activation efforts or patient-centered approaches. The marginal benefit of quality care delivery in terms of this outcome might be slightly lower in patients already practicing excellent or very poor adherence.

These results are consistent with previous studies that have examined the association between elements of the CCM and medication adherence. In a randomized controlled study of 74 small primary care practices in Germany, Gensichen et al. found that a telephone-based intervention modeled on the CCM led to better medication adherence among patients with depression [18]. Likewise, Kaissi and Parchman found that self-management support, one of the central 6 CCM elements, was positively associated with medication adherence in an observational, cross-sectional study of patients with Type 2 diabetes [17]. Recent work by Parchman et al. found that participatory decision making and strong patient-provider communication during primary care encounters among patients with type 2 diabetes predicted patient activation and subsequently improved medication adherence [14]. Similarly, Zeber and colleagues found that patients who experienced a stronger therapeutic alliance with their physician sustained higher levels of adherence as defined by the same Morisky scale employed here [16]. In fact, the patient-provider relationship proved more influential to adherence that even medication cost issues [21].

Other studies not specifically incorporating the CCM as a theoretical framework have also found that enhancing self-management support improves medication adherence. In a study of patients with COPD, Khdour et al. found that participation in a pharmacist-led intervention designed to improve self-management behavior was positively associated with adherence [27]. Similarly, Janson et al. found that engagement in individualized self-management education improved long-term adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in patients with asthma [28]. In contrast, a study by Schmittdiel et al. evaluated the relationship between PACIC scores and several patient-centered measures of health care quality, yet found no direct influence upon medication adherence as defined by missed doses during the past 7 days [22]. However, the authors acknowledged that because more than 90% of patients reported complete adherence over a week period, there may not have been enough variation to detect a relationship.

The goal of the present study was not only to examine the association between CCM implementation and medication adherence, but to determine if patients’ experiences of how chronic care was delivered changed their medication prescription behavior when cost was perceived as a barrier. Although variation across clinics was not examined, we observed that higher PACIC scores were not positively associated with adherence equally across all patients in this study. This might suggest that patients’ experiences of their own treatment, even in practices that implemented CCM elements to a greater degree, is an important but insufficient factor to significantly alter global adherence in the face of financial pressures. Other clinical or organizational efforts, such as ongoing provider efforts to understand adherence barriers, targeting health beliefs regarding medication benefits, or an efficient prescription reminder system, for example, might also be necessary to improve adherence in other patients.

Several limitations of this study are worth pointing out, beginning with the reliance on self-reported perceptions and the nature of a cross-sectional study design. There are also unmeasured factors explaining the relationship between medication adherence and cost burden. These might include patient characteristics such as health literacy and the difficulty balancing multiple prescriptions for several chronic conditions, along with provider characteristics such as knowledge of prescription drug costs and ability to foster patient trust, and organizational system factors such as barriers to refilling prescriptions and applying for health benefits [2, 10, 29]. With its emphasis on enhancing patient self-efficacy, improving patient-provider communication, and facilitating access to health systems, the CCM has the potential to address some of these barriers to improving medication adherence [15]. Secondly, other complex, perhaps less modifiable factors, such as ethnicity and sociocultural influences, cognitive ability, mental health status, medication beliefs and illness insight, and lack of social support were not addressed here [21, 30]. In addition, patients were not asked about the specific prescriptions they take; the number and type of medications has been shown to impact cost-related adherence, yet we were unable to incorporate such information in the current analysis [2]. Finally, we note that PACIC responses were skewed towards higher values, which may have masked some potential positive effects upon medication adherence. It is difficult to determine whether patients who reported their providers “always” engaged in the 20 PACIC activities were reflecting honestly upon care received or could rely upon an accurate basis of comparison regarding chronic care delivery. More in-depth, qualitative approaches to understanding patient and even provider perspectives could undoubtedly complement the survey response data. Nevertheless, this generalizable study provides important insights on a much larger cohort than prior PACIC reports, which examined sample sizes of roughly 280–450 patients.

In conclusion, patients’ experiences of chronic illness care in the primary care setting and their medication cost burden are both independently associated with overall medication adherence. However, the quality of these care experiences and extent to which they reflect good chronic care delivery did not substantially attenuate the relationship between medication adherence and cost-related burdens. Therefore, it remains likely that additional efforts to target other leverage points, such as shared decision-making or the therapeutic alliance, might further encourage highly activated patients involved in their own treatment. Thus it is reasonable to suggest that better chronic care delivery can target adherence through other mechanisms, such as a patient-centered treatment partnership that improves health beliefs or attitudes towards medications and adherence behavior. Additional research will be needed to elucidate whether specific CCM elements, and other clinic organizational or non-economic factors, might represent a crucial dimension necessary to influence patients’ decisions regarding medication use in response to financial pressures.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nedal Arar, Raymond Palmer, and Laurel Copeland for additional suggestions and contributions to this manuscript. This project was supported by funding provided through award number NIH/NIDDK R18DK075692 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors have any conflicts of interests, financial or in terms of personal relationships, that could potentially bias this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2868–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piette JD, et al. A conceptually based approach to understanding chronically ill patients’ responses to medication cost pressures. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(4):846–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karter AJ, et al. New prescription medication gaps: a comprehensive measure of adherence to new prescriptions. Health Services Research. 2009;44(5):1640–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zivin K, et al. Factors influencing cost-related nonadherence to medication in older adults: a conceptually based approach. Value in Health. 2010;13(4):338–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1782–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinman MA, Sands LP, Covinsky KE. Self-restriction of medications due to cost in seniors without prescription coverage. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(12):793–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurlander JE, et al. Cost-Related Nonadherence to Medications Among Patients With Diabetes and Chronic Pain: Factors beyond finances. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2143–2148. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piette JD, et al. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(15):1749–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EH, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T. Interventions to improve chronic illness care: evaluating their effectiveness. Disease Management. 2003;6(2):63–71. doi: 10.1089/109350703321908441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeber JE, et al. Diabetes and medication adherence: the association between perceived drug costs and the therapeutic alliance. Veterans Affairs HSRD annual meeting; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parchman ML, Zeber JE, Palmer RF. Participatory decision making, patient activation, medication adherence, and intermediate clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a STARNet study. Annals of Family Medicine. 2010;8(5):410–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman K, et al. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeber JE, et al. Therapeutic alliance perceptions and medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;107(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaissi AA, Parchman M. Organizational factors associated with self-management behaviors in diabetes primary care clinics. Diabetes Educator. 2009;35(5):843–50. doi: 10.1177/0145721709342901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gensichen J, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: a cluster randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(6):369–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parchman ML, et al. A group randomized trial of a complexity-based organizational intervention to improve risk factors for diabetes complications in primary care settings: study protocol. Implementation science. 2008;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George CF, et al. Compliance with tricyclic antidepressants: the value of four different methods of assessment. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2000;50(2):166–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeber JE, et al. Medication Adherence, Ethnicity, and the Influence of Multiple Psychosocial and Financial Barriers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(2):86–95. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmittdiel J, et al. Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and Improved Patient-centered Outcomes for Chronic Conditions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(1):77–80. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, et al. Development and Validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) Medical Care. 2005;43(5):436–444. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160375.47920.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vrijhoef HJ, et al. Quality of integrated chronic care measured by patient survey: identification, selection and application of most appropriate instruments. Health Expectations. 2009;12(4):417–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow RE, et al. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2655–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wensing M, et al. The Patients Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) questionnaire in The Netherlands: a validation study in rural general practice. BMC health services research. 2008;8:182. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khdour MR, et al. Clinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPD. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2009;68(4):588–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janson SL, et al. Individualized asthma self-management improves medication adherence and markers of asthma control. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2009;123(4):840–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson IB. Physician-Patient Communication About Prescription Medication Nonadherence: A 50-State Study of America’s Seniors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(1):6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0093-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Copeland LA, et al. Treatment Adherence and Illness Insight in Veterans With Bipolar Disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196(1):16–21. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318160ea00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]