Abstract

Detection of an extracellular cleaved fragment of a cell-cell adhesion molecule represents a new paradigm in molecular recognition and imaging of tumors. We previously demonstrated that probes that recognize the cleaved extracellular domain of PTPmu label human glioblastoma brain tumor sections and the main tumor mass of intracranial xenograft gliomas. In this manuscript, we examine whether one of these probes, SBK2, can label dispersed glioma cells that are no longer connected to the main tumor mass. Live mice with highly dispersive glioma tumors were injected intravenously with the fluorescent PTPmu probe to test the ability of the probe to label the dispersive glioma cells in vivo. Analysis was performed using a unique 3-D cryo-imaging technique to reveal highly migratory and invasive glioma cell dispersal within the brain and the extent of co-labeling by the PTPmu probe. The PTPmu probe labeled the main tumor site and dispersed cells up to 3.5 mm away. The cryo-images of tumors labeled with the PTPmu probe provide a novel, high-resolution view of molecular tumor recognition, with excellent 3-D detail regarding the pathways of tumor cell migration. Our data demonstrate that the PTPmu probe recognizes distant tumor cells even in parts of the brain where the blood-brain barrier is likely intact. The PTPmu probe has potential translational significance for recognizing tumor cells to facilitate molecular imaging, a more complete tumor resection and to serve as a molecular targeting agent to deliver chemotherapeutics to the main tumor mass and distant dispersive tumor cells.

Keywords: receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase, proteolytic cleavage, glioma, molecular imaging, targeting agent, migration, invasion

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common malignant adult astrocytoma with very low short and long term survival rates.1 It is characterized as having a necrotic main tumor mass accompanied by high dispersal of individual or clusters of tumor cells along blood vessels and white matter tracts in the brain. Currently the best treatment for GBM is surgical resection of the main tumor mass, followed by radiotherapy and temozolomide chemotherapy.2 The extent of surgical resection of the main tumor mass has a significant effect on overall survival,3–5 especially when combined with radio- and chemotherapy.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently used to delineate the tumor border prior to tumor resection. Unfortunately, this is an imperfect tool, as the contrast enhancement agent, gadolinium, has highly variable labeling results and cannot highlight individual GBM cells that have migrated away from the main tumor mass,6 nor can a static image taken before surgery be used as a real-time intra-operative guide. Imaging of the dispersed tumor cell population in addition to the main tumor mass prior to surgery would provide a significant advantage to the surgeon.

The development of tools to molecularly label tumor cells to aid in surgical resection is a major focus of current cancer research.7 To this end, we have studied a cleaved and shed extracellular fragment of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase (RPTP) PTPμ that is found in the tumor microenvironment. Full-length PTPμ has both cell adhesion and signaling capabilities. The extracellular segment of full-length PTPμ has a MAM (meprin, A5/neuropilin, mu) domain, an immunoglobulin (Ig) domain and four fibronectin type III (FNIII) repeats. The MAM and Ig domains as well as the first two FNIII repeats are required for efficient cell-cell adhesion.8–14 The intracellular segment of full-length PTPμ has two tyrosine phosphatase domains15 of which only the membrane proximal tyrosine phosphatase domain is catalytically active.16

PTPμ extracellular fragment is detected in human GBM tissue and in glioma cells.17, 18 It consists of the MAM, Ig and first two FNIII repeats of full-length PTPμ,18 and thus should be able to bind homophilically to other PTPμ molecules. PTPμ is cleaved either by a matrix metalloprotease (MMP) or A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease (ADAM) to yield the PTPμ extracellular segment and a membrane-tethered fragment consisting of the transmembrane and intracellular domains.17 The membrane-tethered fragment is subsequently cleaved by the gamma secretase complex to give rise to a membrane-free intracellular fragment capable of translocating to the cell nucleus where it remains catalytically active.17

Fluorescently-labeled targeted PTPμ peptide probes capable of binding homophilically to the shed PTPμ extracellular fragment label tumor cells in sections taken from human GBM tissue whereas scrambled versions of these probes do not bind tumors.18 The edge samples of human GBM tumors contain the PTPμ extracellular fragment and are labeled by these probes.18 However, the PTPμ probes do not bind endogenous full-length PTPμ in the normal (epileptic) brain, likely due to steric hindrance induced by the engagement of full-length PTPμ-PTPμ homophilic binding.18 The most effective of the fluorescently-labeled PTPμ probes, SBK2 and SBK4, can also label flank and intracranial xenograft tumors of human glioma cells when injected into the tail vein of nude mice.18 While the main tumor mass and the tumor edge could be labeled with the probes in vivo, the probes were not tested in an invasive/dispersive model. Since conventional imaging techniques such as MRI are limited to visualizing the main tumor mass, we examined the ability of the PTPμ probe to label migrating and dispersive cells that have moved away from the main tumor mass.

In order to evaluate tumor cell dispersal in the complex architecture of the adult brain, we developed a cryo-imaging system and analysis algorithms that create a three dimensional rendering of fluorescently labeled cells in both the main tumor and in dispersed cells.19, 20 Using this cryo-imaging system, we identified two highly dispersive cell lines, CNS-1 rat glioma cells and LN-229 human glioma cells, that form intracranial tumors much like those observed in human GBM, with large populations of dispersive cells that migrate great distances along both blood vessels and white matter tracts.20 Due to the resolution of the cryo-imaging system, single fluorescently labeled cells can be visualized in three dimensions in the brain.20

In the current study, we evaluated the ability of the fluorescent PTPμ probe to label the adjacent microenvironment of dispersed cell populations of CNS-1-GFP and LN-229-GFP intracranial tumors as assayed using the 3-D cryo-imaging system. Live mice bearing brain tumors were injected intravenously with the Cy5 PTPμ probe. Brains were imaged post-mortem using whole-brain macroscopic fluorescence imaging and the cryo-imaging system.18–20 Fluorescent signals were analyzed to determine the co-localization of the Cy5 labeled PTPμ probe with the GFP labeled dispersed tumor cells in the entire mouse brain. The 3-D cryo-imaging system and analysis indicates that the PTPμ probe detected 99% of tumor cells at the main tumor site and in dispersed cells up to 3.5 mm from the main tumor. Therefore, the PTPμ imaging probe has potential translational significance for molecular imaging of tumors, guiding a more complete resection of tumors and to serve as a molecular targeting agent to deliver chemotherapeutics to the main tumor mass and distant dispersive tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Peptide synthesis and conjugation

The SBK2 peptide (GEGDDFNWEQVNTLTKPTSD) and a scrambled sequence of the SBK2 peptide (GFTQPETGTDNDLWSVDNEK) were synthesized using a standard Fmoc based solid phase strategy with an additional N-terminal glycine residue in the laboratory of Dr. Z.-R. Lu as previously described.18 Following synthesis, the N-terminal glycine residues of the SBK2 and scrambled probes were conjugated to Cy5 NHS ester dye (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA).

Orthotopic xenograft intracranial tumors

Approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University were followed for all animal procedures.

CNS-1 (from Mariano S. Viapiano21) or LN-229 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia) cell lines were infected with GFP encoding lentivirus and used for intracranial implantation in 4–6 week old NIH athymic nude male mice (NCr-nu/+, NCr-nu/nu 20–25 g each) as previously described.20 GFP fluorescence in 100% of cells was verified prior to use in intracranial implants. The CNS-1 cell line was authenticated by Research Animal Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Missouri (Columbia, MO) for interspecies and mycoplasma contamination by PCR analysis. A total of 5×104 (LN-229) or 2×105 (CNS-1) cells were implanted per mouse.

In vivo labeling of intracranial tumors

Imaging experiments were performed at 10–11 days for CNS-1 and 4–8 weeks for LN-229, to allow for optimal tumor growth and cell dispersal of these two cell lines.18, 20 Live mice were injected via lateral tail vein with either SBK2-Cy5 or scrambled-Cy5 probes diluted to 15 μM in PBS (3 nmol total probe delivered). Following a 90-min interval for clearance of unbound probe, the animals were sacrificed and the brains removed for whole-brain imaging using the Maestro™ FLEX In-Vivo Imaging System (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Inc. (CRi), Woburn, MA).18 Immediately after imaging, the brains were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek U.S.A., Inc. Torrance, CA), frozen in a dry ice/ethanol slurry and cryo-imaged. Of note, delivery of multiple doses of either the SBK2-Cy5 or scrambled-Cy5 probes did not result in deleterious effects on mouse health (data not shown).

Cryo-imaging of tissue samples

Frozen brains were alternately sectioned and imaged using the previously described Case Cryo-Imaging System19, 20 at a section thickness of 15 μm and a resolution of 11 µm × 11 µm × 15 µm. Brightfield and fluorescence images were acquired for each of the brains using a low light digital camera (Retiga Exi, QImaging Inc., Canada), an epi-illumination fluorescent light source (Lumen200 PRO, Prior Scientific' Rockland, MA) and fluorescence filters for GFP (Exciter: HQ470/40×, Dichroic: Q495LP, Emitter: HQ500LP) or Cy5 (Exciter: FF01-628/40–25, Dichroic: FF660-Di01-25×36, Emitter: FF01-692/40–25; Semrock, Rochester, NY). Single GFP expressing cells were readily detected with this system. Brightfield and fluorescence exposure settings were identical for SBK2-Cy5 and scrambled-Cy5 probe treated brains. Seven brains implanted with CNS-1-GFP cells and six brains with LN-229-GFP cells were analyzed.

Image processing algorithms for visualization of tumor cells and vasculature

Methodologies for segmentation and visualization of the main tumor mass, dispersing cells, and vasculature have been described.19 Briefly, the main tumor mass was segmented using a fast 3-D region growth algorithm with intensity and gradient-based inclusion/exclusion criteria. Individual slice images were manually edited if necessary. Dispersed cells and clusters were detected by thresholding a Gaussian high pass filter image, discounting the masked main tumor mass. Autofluorescence of normal tissue is not a concern for false positive signals in both red and green channels as it is only less than 1% of the signal found in the vicinity of the main tumor and dispersed cells. Light scattering in tissue might appear as a false positive signal in Cy5 volumes. However, we processed Cy5 volumes with a next-image processing algorithm, and used attenuation and scattering parameters for brain tissue that were previously described.22 Similar parameters were applied for both SBK2-Cy5 and scrambled-Cy5 volumes. To find co-labeled cells/clusters we applied a logical AND operator between the dispersed cell and a Cy5 volume made binary with a threshold. The system is not overly sensitive to variations in the threshold for creating the binary Cy5 volume. The lower limit for the blood vessel detection algorithm was ~ 30 μm diameter. 3-D volumes of tumor, dispersed cells, Cy5 labeled cells, and vasculature were rendered using Amira software (Visage Imaging Inc., San Diego, CA), with modifications developed expressly for cryo-image data. Pseudo-colors were chosen to give the best contrast between the different data volumes. Colors were green (main tumor), yellow (dispersing cells), pink (PTPμ probe labeled dispersed cells), and red (vasculature).

Relative Quantification of Cy5 fluorescence

Cy5 fluorescence intensity of tumors and dispersed cells was quantified by Matlab software using next-image processed volumes for CNS-1 and LN-229 tumors labeled with SBK2-Cy5 or scrambled-Cy5 probes, which normalized the signal to background fluorescence. Total fluorescence signal for each brain was then normalized for tumor volume. SBK2-Cy5 analysis: N=4 tumors for CNS-1 and N=5 tumors for LN-229. Scrambled-Cy5 analysis: N=3 tumors for CNS-1 and N=1 tumor for LN-229.

Distance Analysis of SBK2-Cy5 Probe Labeled Dispersed Cells

The distance between the main tumor mass and dispersed cells was determined using a 3-D morphological distance algorithm.19 Briefly, the algorithm detects the presence of fluorescent voxels in a series of 3-D dilations from the tumor edge outward. Voxel size was 11 µm × 11 µm ×15 µm, approximately the size of single cells. Dilations within 500 μm of the tumor edge were discarded to reduce nonspecific errors and to focus on the population of cells that had dispersed the greatest distance from the main tumor mass. Comparisons were made between the average dispersed cell population and the average SBK2-Cy5 labeled dispersed cell population for each 500 μm distance increment from a total of four brains.

Statistical Analysis

Results from the morphological distance algorithm described above were segmented into incremental distances of 500 μm from the tumor edge, and averaged from four brains. The standard deviation was calculated in Excel from the range of all values within each plotted distance increment for the four brains. The standard error was calculated in Excel using the standard deviation for each data point shown.

Results

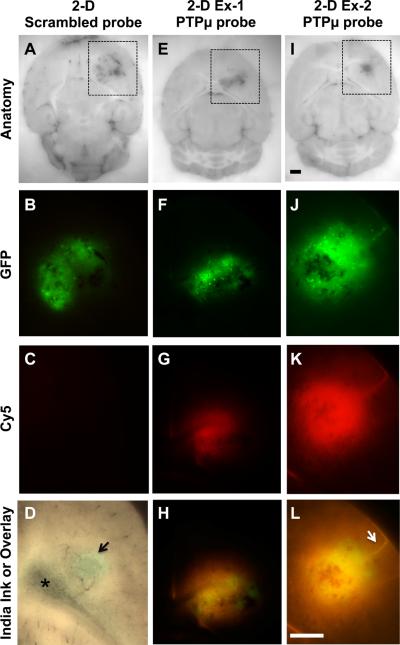

A PTPμ targeted probe was developed for the molecular recognition of glioma cells. Intracranial tumors of glioma cells expressing GFP were labeled with the PTPμ targeted probe (SBK2-Cy5) or with a scrambled version of the PTPμ probe (scrambled-Cy5) through intravenous administration. The main tumors were brightly labeled with the SBK2-Cy5 probe in all cases examined, whereas the scrambled probe resulted in no significant signal above background within the tumor (Fig. 1). Ten day CNS-1-GFP intracranial tumors were labeled in vivo with the PTPμ probe by intravenous injection for 90 minutes prior to sacrifice and post-mortem imaging. This time frame for probe clearance was determined empirically to provide optimal signal to noise (background) ratio of Cy5 fluorescence. The results from the two-dimensional (2D) block face images demonstrate bright PTPμ probe fluorescence (Fig. 1 g,k) within the main GFP-positive tumor (Fig. 1 f,j) in all cases. Cy5 fluorescence signal from PTPμ probe labeling also closely corresponded with the pattern of cell dispersal away from the main tumor (Fig. 1 h,l). In contrast, the scrambled probe did not appreciably label GFP-positive tumor cells above background (Fig. 1 a–c). Quantitation of Cy5 fluorescence intensity from the CNS-1 main tumors and dispersed cell populations labeled with the PTPμ probe was 84.2+/−15.6 (n=4 brains), compared with 7.2+/−2.3 (n=3 brains) for the scrambled probe.

Figure 1.

CNS-1 glioma tumors and dispersing cells are labeled by the PTPμ probe. Unfixed mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells were cryo-imaged following in vivo labeling with scrambled probe (A–C) or PTPμ probe (E–L). Two-dimensional block face images are shown for brightfield (A,E,I), with boxed regions that correspond to the views shown for GFP fluorescence (tumor; B,F,J) and Cy5 fluorescence (scrambled or PTPμ probe; C,G,K) in each column. An overlay of GFP and Cy5 fluorescence demonstrates extensive labeling of the dispersed glioma cells with the PTPμ probe (H,L). In tumors with minimal cell dispersal (F), labeling with the PTPμ probe is localized to the main tumor (G,H). PTPμ probe labels diffusely dispersing cells in a tightly focused pattern when cells migrate as a stream along a defined structure, such as a blood vessel (K,L-see arrow). Brightfield image of a tumor from a brain that was perfused with India Ink (D) to illustrate leakiness of the vasculature. Asterisk in (D) indicates lateral ventricle. Scale bar in (I) represents 1 mm for panels (A, E, I) and the scale bar in (L) represents 1 mm for panels (B–D, F–H, J–L).

Burden-Gulley, et al.

The blood-brain barrier is thought to be leaky within the main tumor in humans, a feature that is required for agents such as gadolinium to contrast brain tumors against the normal brain background. We examined the blood brain barrier integrity in our mouse model system by perfusing with dilute India Ink prior to removal of the brain containing a tumor. Vasculature of the perfused brain was contrasted black against the brain parenchyma, and blood vessels that coursed through the tumor were clearly defined. In addition, a small accumulation of India Ink was localized to the main tumor (arrowhead in Fig. 1d), suggesting leakiness of blood vessels confined to the main tumor. Based on this result, we hypothesize that regions distant from the tumor edge likely have an intact blood-brain barrier, suggesting that the PTPμ probe may be able to cross the blood-brain barrier to detect dispersing tumor cells.

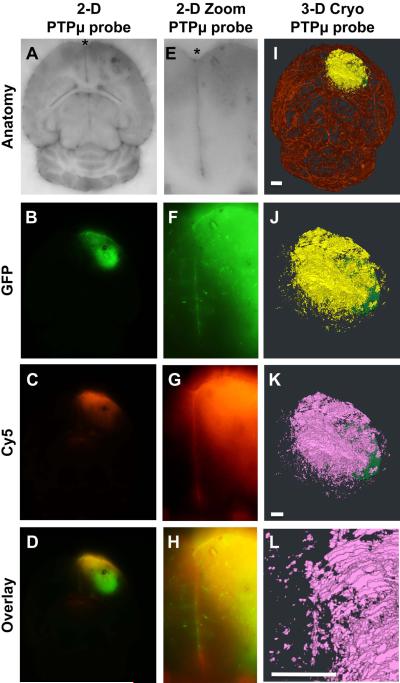

The probe labeled brains were then subjected to cryo-imaging analysis (Fig. 2) as previously described.20 The cryo-imaging system obtained 2-D, microscopic bright-field anatomical images, including vasculature, and multi-spectral fluorescence images of tumor and probe. We refined our previous method19 to segment and visualize the vasculature, main tumor mass, and dispersing cells to highlight the PTPμ probe labeling of only the dispersive glioma cells and cell clusters (refer to Materials and Methods section). 3-D volumes were created for the main tumor mass (pseudo-colored green) and vasculature (pseudo-colored red). Glioma cells no longer physically connected in any dimension to the main tumor were pseudo-colored yellow to indicate tumor cell dispersal. To specifically visualize the PTPμ probe overlay in 3-D, the population of dispersing cells that was co-labeled with the PTPμ probe (Cy5 fluorescence) was pseudo-colored pink by the computer program.

Figure 2.

The PTPμ probe specifically labels CNS-1 glioma cells that have dispersed from the main tumor. Unfixed mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells were cryo-imaged following in vivo labeling with PTPμ probe (A–H). Two-dimensional block face images are shown for brightfield (A,E), GFP fluorescence (tumor; B,F) and Cy5 fluorescence (PTPμ probe; C,G). An overlay of GFP and Cy5 fluorescence demonstrates extensive labeling of the dispersed glioma cells with the PTPμ probe (D,H). A high magnification image demonstrates that the PTPμ probe labels a stream of dispersing tumor cells (F) at the midline (asterisk) (G,H). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the tumor labeled with PTPμ probe is illustrated as main tumor (green), and dispersing cells (yellow) in a magnified view (J). Complete vasculature for this brain specimen is also shown (I). Dispersed cells co-labeled with PTPμ probe are pseudo-colored pink (K). (L) A magnified view of the tumor shown in (K) illustrates co-labeled cells along the midline, which correspond with the labeled midline cells in the 2-D overlay image (H). Scale bar in (I) represents 1 mm for panels (A–D,I). Scale bar in (K) represents 500 μm for panels (J–K). Scale bar in (L) represents 500 μm for panels (E–H,L).

Burden-Gulley, et al.

The rat CNS-1 glioma cell line rapidly disperses to distances of several millimeters from the main tumor.20 A gradient of PTPμ probe fluorescence (Fig. 2 c,g) was observed that encompasses the wave of GFP-positive cell dispersal from the tumor (Fig. 2 b,f,j). Streams of CNS-1-GFP cells migrating along a defined structure were highlighted against the background tissue by the PTPμ probe (Fig. 2 g,h,k,l).

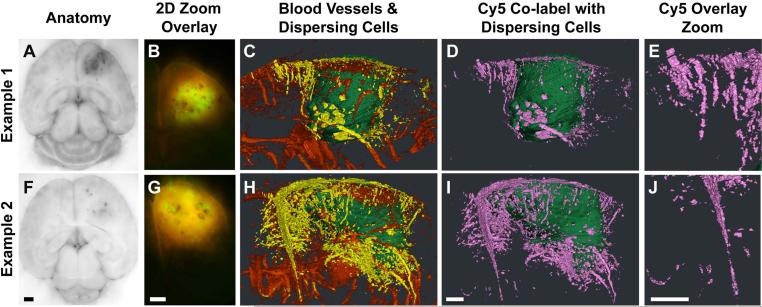

We have previously shown by immunoblot that the dispersive edge region of human glioblastoma tumors accumulates the PTPμ extracellular fragment,20 even though the tumor edge is comprised of normal brain cells and some dispersed tumor cells. In this study, the PTPμ probe fluorescent signal was often brighter in the region of lower GFP-fluorescence, which corresponds to the area of tumor cell dispersal, than it was in the main tumor, which has higher GFP fluorescence (Fig. 2 b–d and f–h). This result suggests that the dispersed cells may have more cleaved PTPμ extracellular fragment deposited in their adjacent microenvironment than in the main tumor, as recognized by the PTPμ probe. A magnified version of that same brain at the midline region of the frontal pole (asterisk) shows GFP dispersing cells (Fig. 2f) are labeled with the PTPμ probe (Cy5: Fig. 2 g–h) in two-dimensional block face images. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the tumors illustrates a GFP-positive main tumor (pseudo-colored green) with a large population of GFP-labeled cells that disperse in many directions (pseudo-colored yellow) (Fig. 2i and j). Analysis of the PTPμ probe labeling of GFP-positive dispersed cells (pseudo-colored yellow) with the binary Cy5 volume indicates that greater than 99% of the total dispersed cells were co-labeled with the PTPμ probe (pseudo-colored pink) (Fig. 2k and l and Fig. 4). Evaluation of additional CNS-1-GFP intracranial tumors labeled with the PTPμ probe demonstrated that the probe was highly effective at labeling the dispersed cell population (Fig. 3). In the two examples shown, a substantial amount of cell dispersal is evident over the brain vasculature in many directions (Fig. 3c and h).

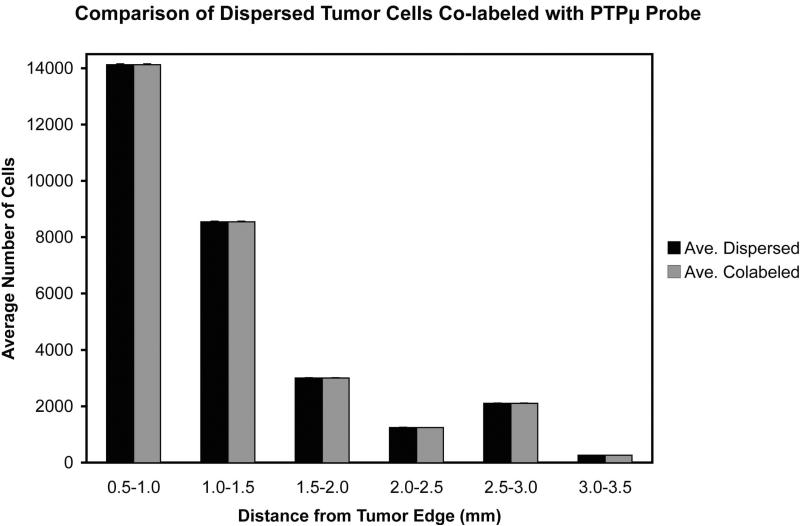

Figure 4.

Histogram of the average number of GFP positive dispersing cells co-labeled with the PTPμ probe per unit distance from the main tumor, +/− standard error (n=4 tumors analyzed).

Burden-Gulley, et al.

Figure 3.

3-D views of dispersed cells from CNS-1 intracranial tumors labeled by the PTPμ probe. Unfixed mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing CNS-1 cells were cryo-imaged and reconstructed in 3 dimensions following in vivo labeling with the PTPμ probe. Two-dimensional block face images are shown for brightfield (A,F), and 2-D block face zoomed overlay of GFP (tumor) and Cy5 fluorescence (PTPμ probe; B,G) for two brain tumors. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the same tumor specimens showing the main tumor mass (pseudo-colored green), dispersed tumor cells (pseudo-colored yellow), and vasculature (pseudo-colored red) illustrate that the dispersing cells often migrate on blood vessels (C,H). The total dispersing cell population is extensively co-labeled with the PTPμ probe (D,I), as shown pseudo-colored pink. Magnified views from (D,I) illustrate that PTPμ co-labeled cells are detected several millimeters from the main tumor (E,J). Scale bar in F represents 1 mm for panels (A,F) and scale bar in G represents 1 mm for panels (B,G). Scale bar in I represents 500 μm for panels (C–D, H–I) and the scale bar in J represents 500 μm for panels (E, J).

Burden-Gulley, et al.

Further analysis of the PTPμ probe-labeled CNS-1 intracranial tumors was performed to determine how far away from the main tumor mass dispersed cells could be labeled with the probe. Four CNS-1 intracranial tumors were analyzed to determine the total number of the dispersing cell population that was co-labeled with the PTPμ probe. The data were segmented into incremental distances of 500 μm from the tumor edge, and then averaged from the four brains. Based upon the algorithms, the results show that the PTPμ probe co-labels 99% of the dispersed cells to a maximum distance of 3.5 mm from the tumor edge (Fig. 4). In fact, the PTPμ probe is able to label even the distant dispersed tumor cells in multiple directions many millimeters from the main tumor mass (Fig. 3 d,e,i,j as well as Fig. 4).

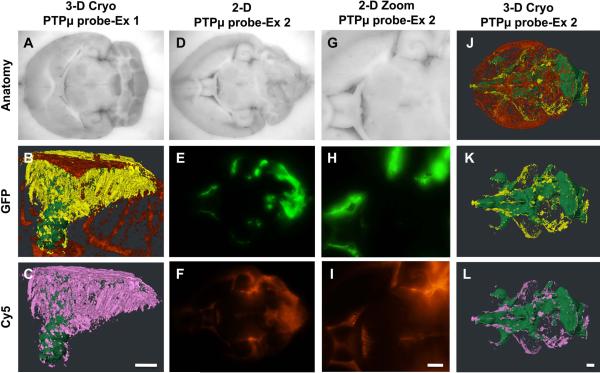

LN-229-GFP intracranial tumors require a minimum of four weeks growth to exhibit appreciable tumor cell dispersal.20 Labeling of LN-229-GFP tumors with the PTPμ probe resulted in a bright Cy5 fluorescence signal within the main GFP-positive tumor, and labeling of greater than 99% of the dispersed cell population (Fig. 5a–c). Quantitation of Cy5 fluorescence from the LN-229 main tumors and dispersed cell populations labeled with the PTPμ probe was 114.7+/−25.9 (n=5 brains), compared with 5.8 (n=1 brain) for the scrambled probe. In rare instances, glioma cells were deposited in close proximity to the lateral ventricle, resulting in extensive spread of cells along the ventricular walls, leptomeningeal regions, within the brainstem and in brain parenchyma at the cerebral/cerebellar junction (3-D reconstruction shown in Fig. 5j–l). Fluorescent signal from the PTPμ probe co-localized with much of this dispersed cell population (Fig. 5d–l).

Figure 5.

Dispersing cells from LN-229 intracranial tumors are specifically labeled by the PTPμ probe. Unfixed mouse brains containing xenografts of GFP-expressing LN-229 cells were cryo-imaged and reconstructed in 3 dimensions following in vivo labeling with the PTPμ probe. Three-dimensional reconstruction of an LN229 tumor (A) shows the main tumor mass (pseudo-colored green), dispersed tumor cells (pseudo-colored yellow) and vasculature (pseudo-colored red) (B). PTPμ probe co-labeling of dispersing cells (pseudo-colored pink) was observed at great distances from the main tumor (C). A second tumor example where the LN229 tumor cells spread through the ventricles of the brain is shown (D–L). Two-dimensional block face images are shown for brightfield (D,G), GFP fluorescence (tumor; E,H) and Cy5 fluorescence (PTPμ probe; F,I). Comparison of GFP (E) and Cy5 (F) fluorescence in zoomed images (H,I) demonstrates extensive overlap in signal in this specimen. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the same tumor specimen is shown (J–L). In addition to the main tumor, the total dispersing cell population is extensively co-labeled with the PTPμ probe as shown pseudo-colored pink (L). Scale bar in (L) represents 500 μm for panels (A, D–F, J–L). Scale bar in (C) represents 500 μm for panels (B,C). Scale bar in (I) represents 500 μm for panels (G–I).

Burden-Gulley, et al.

Results from these experiments suggest that the PTPμ probe crosses the blood-brain barrier to label not only the main tumor mass, but also the vast majority of the dispersed tumor cells at a range up to 3.5 millimeters away from the main tumor mass (Fig. 4). In contrast, the scrambled-Cy5 probe did not label tumors (Fig. 1a–c). The PTPμ probe preferentially labeled the PTPμ extracellular fragment deposited in the adjacent tumor microenvironment of the dispersed cells (Fig. 1g and k). These results suggest that the PTPμ probe is a marker of the microenvironment of the main tumor, tumor edge and dispersing cells, and could be utilized for tumor imaging, a more complete surgical resection or could be a viable molecular targeting agent to deliver therapeutics.

Discussion

Better detection tools for tumor imaging are needed. Molecular recognition of tumor cells would facilitate guided surgical resection. To achieve this goal, targeted imaging tools must specifically label tumor cells, not only in the main tumor but also along the edge of the tumor and in the small tumor cell clusters that disperse throughout the body. To further improve patient survival, probes for the targeted delivery of therapeutics must be developed. The use of the cryo-imaging system allows us to determine whether the PTPμ probe is able to label individual dispersing tumor cells at a great distance from the main tumor within the complex three dimensional environment of the brain. We demonstrate that the PTPμ fluorescent probe is a useful reagent for labeling the main tumor mass and migrating cells, offering a visible means of identifying the dispersed cell population thought to be responsible for tumor recurrence. The kinetics of the PTPμ probe binding to tumors after tail-vein injection demonstrates that it binds within minutes of administration and lasts for as long as 3 hours,18 thus providing a window of time for surgery. The PTPμ probe has a high tumor contrast compared to background, as shown in the cryo-images acquired with a low power objective. Microscopes used in surgical suites typically use higher power objectives with a greater numerical aperture. Since there is a direct relationship between numerical aperture and fluorescence brightness, the signal to noise ratio of the SBK2-Cy5 probe would be further improved in the surgical setting. Clinical safety of the probe would need to be evaluated, but our preliminary findings show no toxicity of the probe. However, we have not performed any formal toxicology studies with the probe to date.

Greater than 50% of tumor volume resection has been shown to be achievable through fluorescence guided-resection of tumor tissue using the Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA)-Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) system,3 which visualizes fluorescently-detectable PpIX, produced as a result of exogenously introduced ALA.23 In addition to the ALA-PpIX system, other fluorescent labeling agents have been developed to label the main tumor (for review see24). Targeted fluorophores against the EGF receptor type II (EGFR2/HER2) and VEGF receptors as well as folate receptor α have been used to intra-operatively label xenograft models of breast, ovarian and gastric cancers (in the case of HER2 and VEGFR)25 and ovarian cancer (in the case of the folate receptor α).26 Protease activatable fluorophores have also been used to detect tumor cells.24 For example, the protease cathepsin is enriched in the tumor microenvironment. A cathepsin-activated near-infrared fluorescent probe is effective at intra-operatively labeling breast cancer cells in a rat tumor model.27 An activatable cell-penetrating peptide (ACPP) conjugated to Cy5 is taken up by cancer cells only after proteolytic cleavage by matrix metalloproteases 2 or 9.28, 29 The use of the ACPP-Cy5 probe as an intra-operative guide for surgery in mouse tumor models resulted in fewer cancer cells being left behind and better tumor-free and overall survival than in mice that underwent surgery without the fluorescent probe as a guide.28

The ALA-PpIX system has significant clinical utility in surgical resection of GBM, but its use results in only 50.2% of patients having complete tumor resection.5 It is unclear why only 50% of the patients respond. This may be the limit for improving upon surgical resection of brain tumors, but we hypothesize that better detection of dispersive cells in GBM would enhance the ability to completely resect a tumor. While the ACPP-Cy5 probe is promising for tumor labeling outside of the brain28, the addition of a large molecular weight carrier to the ACPP (ACPP-D) to facilitate tumor uptake and reduce background fluorescence, produces a molecule that may be too large, ~28 kD,30 to cross the blood-brain-barrier. We hypothesize that the PTPμ probe could be an improvement upon existing intraoperative labeling technologies due to its small size (~3 kD), and its ability to label virtually all of the highly dispersive cells that are characteristic of GBM, the very cells that are responsible for recurrence and the terminal nature of the disease.

Probes designed to label molecules that accumulate in the tumor microenvironment may also be advantageous as therapeutic targeting agents, as they can identify both the main tumor cell population and areas with infiltrating cells that contribute to tumor recurrence. The PTPμ probe labels the shed PTPμ extracellular fragment that accumulates in the tumor microenvironment, but is not present in normal brain.18 For this reason, the PTPμ probe could also be used to deliver therapeutics to the tumor microenvironment, including chemotherapy, directly to all tumor and any infiltrating stromal cells. The animals were sacrificed 90 minutes after probe injection, a time interval too short to observe any biological effects of the probe. It is currently unknown whether use of the PTPμ probe affects tumor cell dispersal/invasion. Future studies will address the long-term clearance and biological effects of the probes in vivo. The ability to directly target the tumor microenvironment would increase both the specificity and sensitivity of current treatments, therefore reducing non-specific side effects of chemotherapeutics that affect all cells of the body.

Cleavage of many cell surface proteins by ADAM and/or MMPs occurs in tumor tissue,31, 32 and is likely due to the increased expression of proteases in the adjacent tumor microenvironment, especially at tumor margins.33 The techniques described for the development of fluorescently-labeled PTPμ probes may also be used to develop probes to other proteins that are cleaved in GBM and other tumor types.31

Novelty and Impact Statement.

One of the main challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of glioblastoma multiforme is the frequent dispersal of tumor cell clusters along blood vessels or neuronal tracks away from the main tumor mass. The authors developed a new molecular imaging probe for gliomas using an extracellular cleaved fragment of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu. The PTPmu probe detects invading tumor cells that are several millimeters away from the main tumor, as visualized in three dimensions with a unique cryo-imaging technique. This new technique promises to facilitate molecular imaging of gliomas, may allow a more complete tumor resection and may even serve as a molecular targeting agent to deliver therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Debashish Roy, Lebing Li and Scott Becka for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by the following NIH grants: R01-NS063971 (S.B.-K., J.P.B., Z.-R.L. and D.W.), R42-CA124270 (D.W.), and P30-CA043703 (S.B.-K. and J.P.B). This work was also supported by grants from the Ohio Wright Center/BRTT, The Biomedical Structure, Functional and Molecular Imaging Enterprise (DW), the Case Center for Imaging Research and the Tabitha Yee-May Lou Endowment Fund for Brain Cancer Research. This research was also supported by the Athymic Animal Core Facility of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals of Cleveland (P30 CA43703).

List of nonstandard abbreviations

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- PTPμ

receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu;

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Wilson has a financial interest in BioInVision Inc., which is commercializing cryo-imaging.

References

- 1.Kohler BA, Ward E, McCarthy BJ, Schymura MJ, Ries LA, Eheman C, Jemal A, Anderson RN, Ajani UA, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2007, featuring tumors of the brain and other nervous system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:714–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichlmeier U, Bink A, Schackert G, Stummer W. Resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: an RTOG recursive partitioning analysis of ALA study patients. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:1025–34. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ewelt C, Goeppert M, Rapp M, Steiger HJ, Stummer W, Sabel M. Glioblastoma multiforme of the elderly: the prognostic effect of resection on survival. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:611–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stummer W, Reulen HJ, Meinel T, Pichlmeier U, Schumacher W, Tonn JC, Rohde V, Oppel F, Turowski B, Woiciechowsky C, Franz K, Pietsch T. Extent of resection and survival in glioblastoma multiforme: identification of and adjustment for bias. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:564–76. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000317304.31579.17. discussion -76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerstner ER, Sorensen AG, Jain RK, Batchelor TT. Advances in neuroimaging techniques for the evaluation of tumor growth, vascular permeability, and angiogenesis in gliomas. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:728–35. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328318402a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neuro-oncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.20069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aricescu AR, Hon WC, Siebold C, Lu W, van der Merwe PA, Jones EY. Molecular analysis of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu-mediated cell adhesion. Embo J. 2006;25:701–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aricescu AR, Jones EY. Immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecules: zippers and signals. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aricescu AR, Siebold C, Jones EY. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase mu: measuring where to stick. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:167–72. doi: 10.1042/BST0360167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brady-Kalnay SM, Tonks NK. Identification of the homophilic binding site of the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP mu. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28472–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cismasiu VB, Denes SA, Reiländer H, Michel H, Szedlacsek SE. The MAM (meprin/A5-protein/PTPmu) domain is a homophilic binding site promoting the lateral dimerization of receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase mu. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26922–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Vecchio RL, Tonks NK. The conserved immunoglobulin domain controls the subcellular localization of the homophilic adhesion receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase mu. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1603–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zondag GC, Koningstein GM, Jiang YP, Sap J, Moolenaar WH, Gebbink MF. Homophilic interactions mediated by receptor tyrosine phosphatases mu and kappa. A critical role for the novel extracellular MAM domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14247–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gebbink MF, van Etten I, Hateboer G, Suijkerbuijk R, Beijersbergen RL, Geurts van Kessel A, Moolenaar WH. Cloning, expression and chromosomal localization of a new putative receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase. FEBS Lett. 1991;290:123–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81241-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gebbink MF, Verheijen MH, Zondag GC, van Etten I, Moolenaar WH. Purification and characterization of the cytoplasmic domain of human receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase RPTP mu. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13516–22. doi: 10.1021/bi00212a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgoyne AM, Phillips-Mason PJ, Burden-Gulley SM, Robinson S, Sloan AE, Miller RH, Brady-Kalnay SM. Proteolytic cleavage of protein tyrosine phosphatase mu regulates glioblastoma cell migration. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6960–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burden-Gulley SM, Gates TJ, Burgoyne AM, Cutter JL, Lodowski DT, Robinson S, Sloan AE, Miller RH, Basilion JP, Brady-Kalnay SM. A novel molecular diagnostic of glioblastomas: detection of an extracellular fragment of protein tyrosine phosphatase mu. Neoplasia. 2010;12:305–16. doi: 10.1593/neo.91940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Burden-Gulley SM, Lu H, Roy D, Wang J, Basilion JP, Brady-Kalnay SM, Wilson DL. Cryo-image Analysis of Tumor Cell Migration, Invasion, and Dispersal in a Mouse Xenograft Model of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. Mol Imaging Biol. 2012;14:572–83. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0525-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burden-Gulley SM, Qutaish MQ, Sullivant KE, Lu H, Wang J, Craig SE, Basilion JP, Wilson DL, Brady-Kalnay SM. Novel cryo-imaging of the glioma tumor microenvironment reveals migration and dispersal pathways in vivid three-dimensional detail. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5932–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruse CA, Molleston MC, Parks EP, Schiltz PM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Hickey WF. A rat glioma model, CNS-1, with invasive characteristics similar to those of human gliomas: a comparison to 9L gliosarcoma. J Neurooncol. 1994;22:191–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01052919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steyer GJ, Roy D, Salvado O, Stone ME, Wilson DL. Removal of out-of-plane fluorescence for single cell visualization and quantification in cryo-imaging. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:1613–28. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9726-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogue BW, Gibbs-Strauss S, Valdes PA, Samkoe K, Roberts DW, Paulsen KD. Review of Neurosurgical Fluorescence Imaging Methodologies. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2010;16:493–505. doi: 10.1109/JSTQE.2009.2034541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keereweer S, Kerrebijn JD, van Driel PB, Xie B, Kaijzel EL, Snoeks TJ, Que I, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Mieog JS, Vahrmeijer AL, van de Velde CJ, et al. Optical image-guided surgery--where do we stand? Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwisscha van Scheltinga AG, van Dam GM, Nagengast WB, Ntziachristos V, Hollema H, Herek JL, Schroder CP, Kosterink JG, Lub-de Hoog MN, de Vries EG. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence tumor imaging with vascular endothelial growth factor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 targeting antibodies. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1778–85. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dam GM, Themelis G, Crane LM, Harlaar NJ, Pleijhuis RG, Kelder W, Sarantopoulos A, de Jong JS, Arts HJ, van der Zee AG, Bart J, Low PS, et al. Intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging in ovarian cancer by folate receptor-alpha targeting: first in-human results. Nat Med. 2011;17:1315–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mieog JS, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Kuppen PJ, Que I, Dijkstra J, Kaijzel EL, Prins F, Lowik CW, Smit VT, van de Velde CJ, Vahrmeijer AL. Image-guided tumor resection using real-time near-infrared fluorescence in a syngeneic rat model of primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:679–89. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen QT, Olson ES, Aguilera TA, Jiang T, Scadeng M, Ellies LG, Tsien RY. Surgery with molecular fluorescence imaging using activatable cell-penetrating peptides decreases residual cancer and improves survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4317–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang T, Olson ES, Nguyen QT, Roy M, Jennings PA, Tsien RY. Tumor imaging by means of proteolytic activation of cell-penetrating peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17867–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408191101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson ES, Jiang T, Aguilera TA, Nguyen QT, Ellies LG, Scadeng M, Tsien RY. Activatable cell penetrating peptides linked to nanoparticles as dual probes for in vivo fluorescence and MR imaging of proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4311–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910283107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Fragments of Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases (RPTPs) as Cancer Molecular Diagnostic Tools. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011 doi: 10.2174/187152011794941244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craig SE, Brady-Kalnay SM. Cancer cells cut homophilic cell adhesion molecules and run. Cancer Res. 2011;71:303–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards DR, Handsley MM, Pennington CJ. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:258–89. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]