Abstract

Vascular adhesion molecules regulate the migration of leukocytes from the blood into tissue during inflammation. Leukocyte binding to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) activates signals in endothelial cells, including Rac1 and calcium fluxes. These VCAM-1 signals are required for leukocyte transendothelial migration on VCAM-1. However, it has not been reported whether the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 is necessary for these signals. Interestingly, the 19 amino acid sequence of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is 100% conserved among many mammalian species, suggesting an important functional role for the domain. To examine the function of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, we deleted the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain or mutated the cytoplasmic domain at amino acids N724, S728, Y729, S730 or S737. The cytoplasmic domain and S728, Y729, S730 or S737 were necessary for leukocyte transendothelial migration. The S728 and Y729, but not S730 or S737, were necessary for VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes. In contrast, the S730 and S737, but not S728 or Y729 were necessary for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1. These functional data are consistent with our computational model of the structure of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain as an alpha helix with S728/Y729 and S730/S737 on opposite sides of the alpha helix. Together, these data indicate that S728/Y729 and S730/S737 are distinct functional sites that coordinate VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes and Rac1 during leukocyte transendothelial migration.

Keywords: VCAM-1, cytoplasmic domain, computational model, endothelial, Rac1, calcium, leukocyte migration

During inflammation, expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) is induced on endothelial cells. VCAM-1 regulates recruitment of leukocytes into inflamed tissues. Its ligands include the high affinity conformation of the integrins α4β1 and α4β7 expressed on lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells and monocytes 1–7. Chemokine receptors induce activation of these integrins to the high affinity conformation on T cells, B cells, mast cells, eosinophils, or monocytes for migration on VCAM-1. Thus, the cell types that migrate on VCAM-1 during an immune challenge depend on the cell-type specific chemokines in the microenvironment. VCAM-1 regulates eosinophil migration in asthmatic inflammation, T cell trafficking through the blood brain barrier during multiple sclerosis, and the development of atherosclerotic plaques in cardiovascular disease 8–10. Additionally, VCAM-1−/− mice are embryonic lethal, due to impaired placental and heart development 11. Binding to VCAM-1 activates a signaling cascade in endothelial cells that results in endothelial cell retraction, enabling leukocyte passage from the blood to the tissue 12–19.

VCAM-1 signaling is necessary for VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte migration. Upon antibody crosslinking of VCAM-1, endothelial cell intracellular calcium is released, calcium channels are activated, and Rac1 is activated. Together, calcium fluxes and Rac1 activate endothelial NOX2 15, 20, 21. NOX2 generates low levels of superoxide which dismutates to H2O2. This H2O2 activates matrix metalloproteinases in the endothelial extracellular matrix. The H2O2 also diffuses through the endothelial membrane to oxidize and activate protein kinase C alpha (PKCα) 14, 17. PKCα activation leads to the phosphorylation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) which then induces signals for ERK1/2 phosphorylation 18, 22. Blocking any of these signals disrupts VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration.

While several intermediates in the VCAM-1 signaling cascade have been reported, it has not been determined whether the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is necessary for initiating these signals. The 19 amino acid VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is highly conserved among species. This level of interspecies conservation suggests an important functional role for the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain. Therefore, we hypothesized that the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain initiates the VCAM-1 signaling cascade. In this report, we demonstrated that the cytoplasmic domain is necessary for rapid VCAM-1 signals and VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration. Furthermore, by creating single amino acid point mutations, we identified two amino acids in the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain that are necessary for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1 and two distinct amino acids that are necessary for VCAM-1 activation of calcium, enabling leukocyte transendothelial migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

The endothelial cell line mHEVa was derived from the axial lymph nodes of male BALB/c mice and cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 20% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM HEPES, 10 mM sodium bicarbonate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 50 mg/ml gentamicin as previously described 23. The mHEVa cell line was spontaneously immortalized but not transformed. The mHEVa cell line constitutively expresses VCAM-1, but it does not express the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, MAdCAM or PECAM-1 as determined by flow cytometry and microarray analysis 23. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were from Lonza (catalog #CC-2517). Spleen leukocytes were obtained from BALB/c male mice. Animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Northwestern University (Chicago, IL).

Reagents

Rat anti-mouse VCAM-1 (clone MVCAM.A) was from eBioscience (catalog #550547). FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human ICAM-1 (clone 84H10, catalog # MCA532F) and mouse anti-human ICAM-1 (clone 84H10, catalog #MCA532) were from AbD Serotec. Goat anti-mouse IgG1 (catalog # 1070-01), goat anti-rat IgG (catalog # 3050-01), biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (catalog # 3030-08), biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (catalog # 1034), rat IgG isotype control (catalog # 0108-01), and mouse IgG isotype control (catalog # 0107-01) were from Southern Biotech. FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (catalog #554016) and rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2) (catalog # 553142) were from BD Pharmigen. The pcDNA3.1V5-His-TOPO TA expression kit was from Invitrogen (catalog # K4800). Transfection was performed using TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus, catalog # MIR2300). The QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (catalog # 200524) was from Agilent Technologies. The Halt Protease/Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail was from Thermo Scientific (catalog #78441).

Antibody-coated beads

For anti-mouse VCAM-1-coated beads, streptavidin-coated 9.9 μm diameter beads (80 μl) (Bangs Laboratories) were labeled with 24 μg of biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG in 375 μl of PBS with gentle rocking for 1 h at 4°C and then washed three times 24. These beads were incubated with 16 μg of rat anti-mouse VCAM-1 or a rat isotype IgG control antibody in 375 μl of PBS with gentle rocking for 1 h at 4°C and then washed. For anti-human ICAM-1-coated beads, the streptavidin-conjugated beads were coated with 24 μg of biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and then 16 μg of mouse anti-human ICAM-1 or a mouse isotype IgG control antibody.

Plasmid with the V/I Chimeric Receptor

The V/I chimera was created by ligating in frame the cDNA encoding the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of human ICAM-1 to the cDNA encoding the human VCAM-1 immunoglobulin-like domains 3–7, the transmembrane region and the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1. For this construct, the mRNA for VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 were isolated from TNF-stimulated primary cultures of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and amplified by PCR.

Primers for full length, 7-Ig-like domain human VCAM-1:

Forward: AATTAGGTACCACACACAGGTGGGACACAAA

Reverse:ATATACTCGAGTCTCCAGTTGAACATATCAAGCA

Primers for immunoglobulin-like domains 1 and 2 of human ICAM-1:

Forward: AATTAGGATCCCAGTCGACGCTGAGCTCCTCTGCTA

Reverse: ATATAGATATCAAAGGTCTGGAGCTGGTAGGG

The full-length VCAM-1 was digested with restriction enzymes to remove immunoglobulin-like domains 1 and 2. The remaining VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 sequences were ligated into the pcDNA 3.1V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen, catalog # K4800) backbone plasmid to create the wildtype VCAM-1/ICAM-1 (V/I WT) chimera with a CMV promoter and geneticin resistance gene. To ensure accuracy, the plasmid was completely sequenced at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility.

Plasmid with V/I Receptor Mutations

The following mutants were created using the above V/I chimera plasmid and the Agilent Technologies QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit with the following primers:

Mutant S728A: GAAAAGCCAACATGAAGGGGGCATATAGTCTTGTAG

Reverse: CTACAAGACTATATGCCCCCTTCATGTTGGCTTTTC

Mutant Y729F: GCCAACATGAAGGGGTCAGCTAGTCTTGTAGAAGCAC

Reverse: GTGCTTCTACAAGACTAGCTGACCCCTTCATGTTGGC

Mutant S730A: GCCAACATGAAGGGGTCATATGCTCTTGTAGAAGCACAGAAATC

Reverse: GATTTCTGTGCTTCTACAAGAGCATATGACCCCTTCATGTTGGC

Mutant S737A: CTTGTAGAAGCACAGAAAGCAAAAGTGTAGCTAATGCTTG

Reverse: CAAGCATTAGCTACACTTTTGCTTTCTGTGCTTCTACAAG

Whole tail deletion: GCAAGAAAAGCCTAGATGAAGGGGTCATATAGTCTTGTAGAAGC

Reverse: GCTTCTACAAGACTATATGACCCCTTCATCTAGGCTTTTCTTGC

Mutant N724A: CTTTGCAAGAAAAGCCGCCATGAAGGGGTCATATAG

Reverse: CTATATGACCCCTTCATGGCGGCTTTTCTTGCAAAG

To ensure accuracy, each resulting plasmid was fully sequenced at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility.

Transfection and cloning

The mHEVa cells were grown to 70% confluence in 6-well plates and treated with the TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent and linearized pcDNA 3.1V5-His-TOPO plasmids according to manufacturer protocol. 24 hours after transfection, geneticin selection media was added at a concentration of 0.35mg/mL (as previously determined by cell death dose curve). Transfected cells were sub-cloned into 96-well plates and grown to 90% confluence before being labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-human ICAM-1. V/I construct expression was determined by immuno-labeling with anti-ICAM-1 and flow cytometry or fluorescent microscopy. Positively expressing cells were selected and re-subcloned at least 4 times to ensure clonality. Two individually-generated clones were selected for each construct. To ensure accuracy, the V/I chimeras in the clones were completely sequenced by the Northwestern University Genomics Core.

Rac1 Activation

We followed the protocol from the Millipore Rac1 Activation Assay Kit (Catalog #17-283). mHEVa cells were grown to confluence in 35 mm plates in mHEV culture media 23. To crosslink VCAM-1 or the V/I construct, primary and secondary antibodies were premixed for 5 minutes at room temperature (54 μg anti-VCAM-1 with 30 μg rat anti-mouse IgG1, or 27 μg anti-ICAM-1 with 15 μg mouse anti-human IgG1). mHEVa monolayers were stimulated by antibody crosslinking of VCAM-1 or the V/I construct for 30, 60 or 120 seconds, then the media was immediately removed from the cells, 500 μl of lysis buffer was added and the cells were snap-frozen in an ethanol/dry ice bath. The frozen culture dishes were placed on ice to thaw and the cells were scraped from the dishes and placed in ice-cold eppendorf tubes. The samples were pre-cleared with protein agarose G beads (Millipore catalog # 16-266). 35 μl of each sample was collected in a separate eppendorf tube to determine total Rac1/sample by western blot. The remainder of each sample was added to 10μl Pak-1 PBD beads. The samples were rocked for 2 hours at 4ºC and then the beads were washed 3 times with a magnesium lysis buffer (Millipore Catalog #20-168). Laemli buffer (BIORAD catalog # 161-0737) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol was added to the beads. The samples were boiled for 5 minutes and loaded onto an SDS polyacrylamide gel. Cell lysates or immuno-precipitates were loaded into BioRAD 10% mini-PROTEAN TGX precast gels and were run at 130 volts using the BioRad Mini-PROTEAN system. Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using semi-dry transfer with the BioRad SemiDry apparatus. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in 1%TBS-Tween, and a Rac1 monoclonal antibody was added to the milk/TBS-tween mixture for rocking overnight at 4º C. After 3 washes in TBS-Tween, a secondary goat anti-Mouse IR 800 (Rockland, catalog # 610-132-121) antibody was added at a 1:5000 dilution and the membrane was incubated in 5% milk in 1% TBS-Tween for 1 hour at room temperature. The membrane was washed 3 times in 1%TBS-tween. The membrane was analyzed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LiCor, USA).

Calcium Fluxes

Cells were grown to confluence in 96 well plates and loaded using the Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kit (Invitrogen, catalog # F36206) as detailed in the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the Fluo-4 was resuspended in HBSS with 20mM Probenecid to a 10x concentration (HBSS and probenecid were provided in the kit). The Fluo-4/probenecid solution was diluted to 1x in phenol red free HEV medium 25. The media from the cells (spent media) was removed from each well and 100μl of the 1x fluo-4/probenecid solution was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 37° Celsius and another 10 minutes at room temperature before the fluo-4 solution was replaced with spent media. Spent media was used rather than fresh culture medium because in fresh culture media, serum growth factors stimulate growth factor receptor-mediated calcium fluxes. For cells stimulated with mouse anti-ICAM-1 or mouse isotype control antibody, the wells were pretreated with 4 μg Fc block per 100μl of media (100 μl media per well). The cells were stimulated with 8×106 beads (Bangs Laboratories, catalog #CP01N) coated with rat anti-VCAM-1 antibodies, mouse anti-ICAM-1 antibodies, mouse IgG isotype control antibodies, or rat IgG isotype control antibodies 26. The relative Fluo-4 fluorescence was examined using a 7620 Microplate Fluorimeter (Cambridge Technology, Inc.). For each experiment, treatments were done with quadruplicate wells and calculated as an average minus background. Experiments were done three times.

Lymphocyte Migration Assay under laminar flow

The migration assay was performed as previously described 12. Briefly, endothelial cells were grown to 100% confluence on Nunc Slide-flasks (Thermo Scientific catalog # 177410). Spleen cells were used as a source of cells contiguous with the blood stream that could then migrate across endothelial cells. Spleen cell migration across the mHEV cell lines is stimulated by mHEV cell constitutive production of the chemokine MCP-1 27 and is dependent on adhesion to VCAM-1 26. Splenocytes were isolated from BALB/c male mice. Red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic lysis. The spleen leukocytes were >90% lymphocytes as previously reported 12. The slides were non-treated or pre-treated with blocking anti-VCAM-1 (81μg/slide) or anti-ICAM-1 (50μg/slide) antibody in 1 ml culture medium as indicated for 15 minutes prior to running the assay. The amount of function blocking antibody used per slide was determined by a dose curve with the wildtype V/I chimera cell lines (data not shown). Then, the flask was removed from the slide and the slide was placed in a parallel plate flow chamber with laminar flow. In vivo, in the absence of inflammation, the rapid fluid dynamics of the blood result in blood cells located midstream of the vascular flow 28. However, during inflammation, there is a change in fluid dynamics 28–30. With inflammation, vascular permeability increases yielding fluid flow from the blood into the tissues which likely contributes to contact of blood cells with the endothelium (“margination”) 28, 30. There is also cell contact as the blood cells leave the capillaries and enter the postcapillary venules 29. Therefore, spleen cells (3 x106) were added to the flow chamber at 2 dynes/cm2. Then, to initiate spleen cell contact with the endothelial cells in vitro, the spleen cells were allowed to settle for 5 minutes in the chamber as monitored by microscopy and then 2 dynes/cm2 was applied for the 15 min to mimic post-capillary blood flow 12. We have observed by microscopy that during the assay under laminar flow, the spleen cells in contact with the endothelial cells either roll, roll and detach, or roll, firmly attach, and migrate. After cell contact, the focus of the studies is on mechanisms of transendothelial migration under conditions of laminar flow. For this assay, the co-culture was exposed to laminar flow at 2 dynes/cm2 at 37°C for 15 min to examine cell migration. Then, the cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.2 mM CaCl2 and 0.1 mM MgCl2 because cations are required for cell adhesion. These cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. Then the slides were cover slipped with gelvatol. To quantify migrated spleen cells, phase contrast microscopy was used to count migrated cells that are phase dark 31. In each experiment, 5 high powered fields were counted for each slide. The data are presented as the average ± standard error from 3 slides per treatment. In this assay, the endothelial cells constitutively produce the chemokine MCP-1 to induce the transendothelial migration of leukocytes on VCAM-1 12. It has been reported that the transendothelial migration of an individual leukocyte, after it has rolled to a site of migration, occurs in 2 min 25. However, transendothelial migration of leukocytes is asynchronous. In the laminar flow assay, spleen cell migration is detected by 15 min. The number of spleen cells that were associated but not migrated (phase light cells) at 15 min is low because in 15 min, the majority of non-migrating cells roll off the monolayer of endothelial cells as determined by microscopy (data not shown). Therefore, the number of spleen cells initially associated with the endothelial cells was determined in an adhesion assay.

Lymphocyte Adhesion Assay

The adhesion assay was performed as previously described 12. Briefly, mHEVa cells were grown to confluence in flat-bottomed, tissue culture-treated 96 well plates. Splenocytes were isolated as described in the Migration Assay and then labeled with calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein-AM) (1 μM) at 37°C for 15 minutes and washed three times in PBS. These leukocytes (1×106/well) were added to the mHEVa monolayers. For cell contact, the plate was incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes. To remove nonbound leukocytes, the plates were washed 3 times with PBS with 200 μM MgCl2 and 150 μM CaCl2. The fluorescence was read using a 7620 Microplate Fluorometer (Cambridge Technology, Lexington, MA). A standard curve of fluorescence versus number of leukocytes was used to calculate the number of leukocytes bound to the endothelial cells. To determine leukocyte binding to VCAM-1, the V/I construct was blocked with a blocking anti-ICAM-1 antibody (3 μg antibody/100 μl media; MCA532, AbD Serotec). Likewise, to determine leukocyte binding to the V/I construct, VCAM-1 was blocked with an anti-VCAM-1 blocking antibody (3 μg antibody/100 μl media; eBioscience catalog # 16-1061-85).

Flow Cytometry

Expression of the V/I construct was examined by immuno-labeling with either an isotype control FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG or a monoclonal anti-human ICAM-1 FITC-conjugated antibody. VCAM-1 expression was examined by immuno-labeling with anti-mouse VCAM-1 followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG. Fluorescence was examined by flow cytometry using the BD Biosciences LSR II with analysis using Flow Jo Version 7.2.1.

I-TASSER Molecular Modeling

The VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain sequence was submitted to the I-TASSER program for automated protein structure and function prediction at the University of Michigan 32–34.

Statistics

Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or pairwise T-tests (SigmaStat, Jandel Scientific).

RESULTS

The VCAM-1 Cytoplasmic Domain is highly conserved among species

Entrez-PubMed and Ensemble sequencing indicates that the 19 amino acid VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is highly conserved among mammalian species. There is 100% amino acid sequence identity among human, mouse, rabbit, rat, chimpanzee, rhesus macaque, Sumatran orangutan, common shrew and microbat, with only a one or two amino conserved residue difference for dog, giant panda, horse, dolphin, pig and African Savanna Elephant (Figure 1A). Recognizing the rarity of such species identity, we hypothesized that the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain was necessary for the VCAM-1 outside-in signaling cascade and VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration.

Figure 1. Schematic of the highly conserved 19 amino acid cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 and the VCAM-1/ICAM-1 (V/I) chimeric proteins.

A) The VCAM-1 19 amino acid cytoplasmic domain sequences for the species listed were obtained from Entrez-Pubmed and Ensemble. Conserved amino acids are underlined and in italics. B) The V/I chimeric molecules were created by replacing the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of VCAM-1 with the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of ICAM-1. This chimeric receptor is designated as V/I wild type (V/I WT). C) The V/I chimeric receptor was mutated to delete the cytoplasmic domain or insert specific amino acid substitutions. The V/I receptor with the cytoplasmic domain deletion (V/I ΔCD) was created by inserting a “stop” codon after the alanine (A723) (white arrow). Alternatively, the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain serines, tyrosine, or an asparagine were selected for single point mutations as indicated by the black arrows. The serines and asparagine were mutated to alanines and the tyrosine was mutated to a phenylalanine. mHEV cells were transfected with plasmids containing these mutants and selected for stable expression. At least two separately derived clones were generated for each V/I construct. The V/I in the mHEV clones were completely sequenced to ensure nucleotide sequence accuracy (data not shown).

Generation and characterization of endothelial cells stably expressing VCAM-1/ICAM-1(V/I) chimeric receptors

To gain mechanistic insight into the function of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, we used an established model endothelial cell line, mHEVa, for transfection with VCAM-1 mutation and deletion constructs. This endothelial cell line constitutively expresses VCAM-1 and is the simplest endothelial cell model to examine the functional outcomes of VCAM-1 signaling on leukocyte migration because it does not express other known adhesion molecules for leukocyte binding as determined by microarray and flow cytometry 23. In other endothelial cells, analysis of VCAM-1 function during leukocyte migration is hampered because several adhesion molecules on endothelial cells mediate signaling upon binding leukocytes, thus complicating analysis. To engineer mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 and distinguish these constructs from the endogenously expressed VCAM-1, we created a VCAM-1/ICAM-1(V/I) chimeric receptor (Figure 1B), whereby the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of the chimera are replaced with the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of ICAM-1 and the remainder of the chimera consists of the third immunoglobulin-like domain through the carboxyl cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1. Thus, comparing the signals by endogenous wild type VCAM-1 to the signals by V/I chimeric receptor with mutations is a useful model for studying the function of the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1. Expressing the V/I constructs in mHEVa cells limits the variables because the mHEVa cells do not express other adhesion molecules for leukocytes such as ICAM-1, PECAM-1, MAdCAM, etc. In the mHEVa endothelial cells expressing VCAM-1 and V/I chimeric receptors, VCAM-1 is stimulated by crosslinking with anti-VCAM-1 antibodies, and the V/I chimeric receptors are stimulated by crosslinking with a monoclonal anti-ICAM-1 antibody (84H10) that binds to domain 1 of ICAM-1. Crosslinking is initiated by addition of a secondary antibody.

To determine whether the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is required for VCAM-1 function, we inserted a STOP codon after the first alanine (A723) within the cytoplasmic domain to create a VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain deletion (V/I ΔCD) (Figure 1C). We also hypothesized that the serines and tyrosine may regulate signaling and therefore, we mutated the amino acids S728, Y729, S730 and S737 in the cytoplasmic domain of the V/I WT construct (Figure 1C). To determine whether an amino acid other than serines or the tyrosine are necessary for VCAM-1 signaling, we targeted an uncharged amino acids within the cytoplasmic domain, the asparagine N724 (Figure 1C); we hypothesized that this mutation would not affect VCAM-1 signaling. Each of the serines and the asparagine were mutated to alanine residues and the tyrosine was mutated to a phenylalanine residue (Figure 1C). We expressed each of these constructs in the mHEVa cell line and created at least two separately derived clonal cell lines expressing each V/I construct (Figure 2B) as determined by immuno-labeling with anti-ICAM-1 and flow cytometry. As demonstrated by immuno-labeling with anti-ICAM-1 and flow cytometry, the mHEVa cell line does not express ICAM-1 (Figure 2B) as we previously reported 23. In the cells expressing the mutant V/I chimeric receptors, there was no effect of the transfections on the endogenous surface expression of VCAM-1 as compared to non-transfected mHEV cells as determined by immuno-labeling and flow cytometry (Figure 2A). To compare the molecular weight of the V/I chimeric receptors to V/I WT, VCAM-1 and V/I were immunoprecipitated from V/I WT cells and the V/I mutant cells (Figure 2C). The proteins were analyzed by western blot with anti-VCAM-1, stripped and reprobed with anti-ICAM-1. The V/I WT receptors, V/I mutant receptors and VCAM-1 are about the same molecular weight (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Expression of VCAM-1 and V/I receptors by the endothelial cells.

A) The mHEV clones with stable expression of V/I WT, V/I ΔCD, V/I N724A, V/I S728A, V/I Y729A, V/I S730A, or V/I S737A receptors were immuno-labeled with anti-VCAM-1 primary antibodies (solid lines) or isotype control antibodies (dotted lines) and FITC-conjugated anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies to determine surface VCAM-1 expression by flow cytometry. Shown is a representative graph of one of two separately derived clonal cell lines expressing each V/I chimeric receptor; the flow cytometry profile for the other clone of each chimera was similar (data not shown). B) The clones expressing V/I WT and mutant V/I were immuno-labeled with a FITC-conjugated anti-ICAM-1 antibody to determine V/I expression by flow cytometry. Shown is one representative graph of at least two separately derived clonal cell lines. Dotted lines are the isotype antibody controls. C) The relative molecular weight of VCAM-1 and the V/I proteins were examined by western blot. VCAM-1 or V/I receptors were immuno-precipitated from the endothelial cell clones as indicated and separated by SDS/PAGE. The blots were probed with anti-VCAM-1. Then, the blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-ICAM-1 directed against domain 1 of ICAM-1 to detect the V/I proteins. The V/I WT or the V/I proteins with single amino acid mutations or deletion of the short cytoplasmic domain were relatively the same overall molecular weight as VCAM-1 on SDS/PAGE when compared to the molecular weight standards.

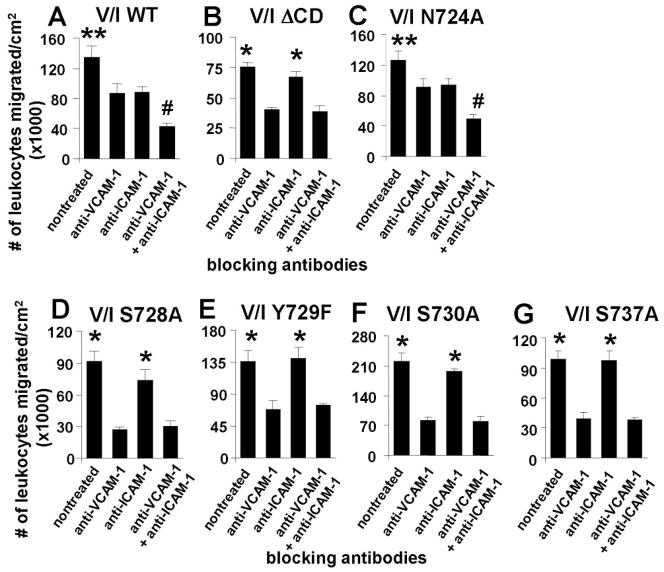

Leukocyte transendothelial migration on VCAM-1 involves the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain amino acids, S728, Y729, S730, and S737, but not N724

We have reported that VCAM-1 signals are required for VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte migration. Therefore, we first determined whether the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain was necessary for VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration in a parallel plate flow chamber with 2 dynes/cm2 laminar flow. Using blocking antibodies, we separately examined leukocyte migration on either the endogenous VCAM-1 or the V/I ΔCD receptors. For these studies, the V/I transfected mHEV cells are the simplest endothelial cell model to examine leukocyte migration as a functional outcome of VCAM-1 signals because primary endothelial cells and other endothelial cell lines express many receptors that mediate leukocyte adhesion, including PECAM-1, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, CD99, selectins, etc. To examine VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte migration, the V/I-transfected mHEV cells were pretreated with saturating levels of adhesion blocking anti-ICAM-1 antibodies that bind ICAM-1 extracellular domain 1. To examine V/I-dependent leukocyte migration, the endothelial cells were pretreated with saturating levels of adhesion blocking anti-VCAM-1 antibodies. In addition, to block both the VCAM-1- and V/I-dependent migration, endothelial cells were pretreated with both anti-VCAM-1 and anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibodies. Thus, under these conditions, we determined whether splenic lymphocyte (>90% lymphocytes) migration was supported by VCAM-1, the V/I WT chimeric receptor, or the V/I ΔCD chimeric receptor. In the V/I WT cell lines, blocking both VCAM-1 and the V/I WT chimeric receptor reduced migration by about 70% as compared to the non-treated controls (Figure 3A); this reduction is similar to our previous report showing a 70% inhibition of lymphocyte migration by anti-VCAM-1 antibody treatment of mHEV cells that are not transfected with a V/I chimera 12. Blocking either VCAM-1 or the V/I chimera in the V/I WT cells resulted in an intermediate level of inhibition of lymphocyte migration (Figure 3A) as compared to the non-treated endothelium. There was no effect of isotype control antibodies as we previously published 12.

Figure 3. The VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain amino acids S728, Y729, S730, and S737 but not N724 are necessary for leukocyte transendothelial migration on VCAM-1.

Leukocyte transendothelial migration across endothelial cells expressing A) V/I WT, B) V/I ΔCD, C) V/I N724A, D) V/I S728A, E) V/I Y729A, F) V/I S730A, or G) V/I S737A was examined under laminar flow in a parallel plate flow chamber. The endothelial cells were pretreated for 15 minutes with the indicated blocking antibodies against VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or both. Secondary antibodies were not added to the cells so the receptors were not activated by antibody crosslinking. Spleen leukocytes were added to each slide and allowed to settle for 5 minutes to initiate leukocyte-endothelial cell contact in the chamber as detailed in the methods. Then, for transendothelial migration, laminar flow was applied for 15 min at 2 dynes/cm2. Migrated cells were determined as phase dark by phase contrast microscopy. Comparisons can only be made within an experiment because total migration can vary somewhat among experiments with the same cell line as previously reported (12). Shown is one representative experiment of 2–3 experiments. The other separately derived clone for each V/I chimera had similar results (data not shown). N = 3 slides per treatment. *, p <0.05 compared to anti-VCAM-1-treated group and anti-VCAM-1+anti-ICAM-1-treated group. **, p<0.05 compared to all groups. #, p<0.05 compared to anti-VCAM-1-treated group and anti-ICAM-1-treated group.

In contrast to the V/I WT chimeric receptor, the receptor with the cytoplasmic domain deletion, V/I ΔCD, did not support splenic lymphocyte transendothelial migration (Figure 3B). Briefly, blocking the V/I ΔCD receptor with anti-ICAM-1, did not inhibit lymphocyte transendothelial migration as compared to the nontreated cells (Figure 3B), suggesting that the V/I ΔCD receptor did not contribute to lymphocyte migration. In contrast, blocking VCAM-1 resulted in a reduction in migration that was similar to blocking both VCAM-1 and the V/I ΔCD receptor, indicating that the lymphocytes had migrated using VCAM-1 and not the V/I ΔCD receptor (Figure 3B). Similar to the V/I ΔCD chimeric receptor (Figure 3B), the V/I mutant receptors S728A, V/I Y729F, V/I S730A and V/I S737A did not contribute to leukocyte transendothelial migration across confluent monolayers of the endothelial cells (Figure 3D–G), indicating that these amino acids have a role in supporting leukocyte transendothelial migration.

To determine whether mutating another amino acid in the cytoplasmic domain affected leukocyte transendothelial migration, we used the V/I N724A construct. Similar to the V/I WT (Figure 3A), antibody blocking of the V/I N724A receptor or the endogenous VCAM-1 inhibited migration compared to nontreated cells (Figure 3C). Moreover, blocking both VCAM-1 and the V/I N724A receptor inhibited migration more than blocking each receptor individually (Figure 3C). Therefore, the V/I N724A mutation did not affect leukocyte transendothelial migration. Thus, S728, Y729, S730 and S737 but not N724 are necessary for leukocyte transendothelial migration.

Transfection with V/I mutants does not alter leukocyte adhesion

We examined endothelial-leukocyte adhesion to the V/I ΔCD receptor or V/I S728A, V/I Y729F, V/I S730A and V/I S737A receptors. Similar to our previous reports with mHEV cells not transfected with a V/I chimera 12, anti-VCAM-1 resulted in a 65–75% inhibition of lymphocyte adhesion (Figure 4). The mutations did not reduce adhesion (Figure 4). Although there was minimal inhibition of total adhesion with anti-ICAM-1 for the initial adhesion of spleen lymphocytes to the clones (Figure 4), the V/I WT receptor but not the V/I serine/tyrosine mutant receptors significantly contributed to the lymphocyte transendothelial migration (Figure 3). Thus, the V/I WT receptor expression levels were high enough to contribute to lymphocyte migration.

Figure 4. Transfection with V/I mutants does not alter leukocyte adhesion.

Leukocyte binding to the endothelial cells expressing V/I WT, V/I ΔCD, V/I N724A, V/I S728A, V/I Y729A, V/I S730A, or V/I S737A was determined at 5 minutes using an adhesion assay. Shown is the mean ±SEM from 3–4 experiments. The other separately derived clone for each V/I chimera had similar results (data not shown). In each experiment, an average was obtained from triplicate wells. *, p <0.05 compared to anti-VCAM-1-treated group and anti- VCAM-1+anti-ICAM-1-treated group.

VCAM-1 activation of Rac1 utilizes the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain amino acids, S730, and S737, but not S728, Y729, or N724

We and others have previously reported that antibody crosslinking of VCAM-1 rapidly activates Rac1 15, 21. The signals downstream of Rac1 are required for VCAM-1 dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration 24, 26, 35. Therefore, we determined whether the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 is required for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1 using the cells expressing V/I WT or V/I mutants. Crosslinking the V/I WT chimeric receptors with an anti-ICAM-1/secondary antibody complex significantly activated Rac1 as compared to the treatment of the cells with an isotype control antibody/secondary antibody complex (Figure 5A). Activation of these cells by crosslinking VCAM-1 with an anti-VCAM-1/secondary antibody complex activated Rac1 (Figure 5A). This 1.5–2 fold increase in Rac1 activity in 30–60 seconds is similar to our previous report with anti-VCAM-1 activation of Rac1 in mHEV cells not expressing V/I chimeric receptors 15. In contrast, when the V/I ΔCD receptors were crosslinked with antibodies, Rac1 was not activated, indicating that the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is necessary for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1 (Figure 5B). As a positive control, Rac1 was activated by antibody crosslinking of the endogenous VCAM-1 on the V/I ΔCD cells (Figure 5B), indicating that the loss in V/I ΔCD receptor activation of Rac1 was due to the loss of the V/I construct cytoplasmic domain and not due to an inability of the endothelial cell lines to activate Rac1.

Figure 5. The VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain amino acids S730, and S737 but not S728, Y729, or N724 are necessary for Rac1 signaling.

To crosslink and activate the V/I chimeric receptors, anti-ICAM-1, which is specific for domain 1 of ICAM-1, was incubated with a secondary antibody for five minutes and then added to endothelial cells expressing A) V/I WT, B) V/I ΔCD, C) V/I N724A, D) V/I S728A, E) V/I Y729A, F) V/I S730A, or G) V/I S737A for 30, 60, and 120 seconds. Then, Rac1 activity was determined. As a positive control, an anti-VCAM-1 plus a secondary antibody was added to the cells to crosslink and activate the endogenous VCAM-1 for 30 or 60 seconds. N = 2–4 experiments for each V/I chimeric receptor. The blots are representative blots. The data in the graphs are the average of the two separately derived clones for each V/I chimeric receptor. *, p <0.05 compared to isotype antibody control.

Antibody crosslinking of the V/I N724A, V/I S728A, or V/I Y729F receptors activated Rac1 (Figure 5C,D,E), suggesting that these three amino acids were not necessary for initiating VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain activation of Rac1. The positive control, antibody crosslinking of the endogenous VCAM-1, activated Rac1 in the cells expressing V/I N724A, V/I S728A, or V/I Y729F receptors (Figure 5C,D,E). In contrast to these amino acids, antibody crosslinking of the V/I S730A receptors or the V/I S737A receptors did not activate Rac1 (Figure 5F,G), demonstrating that these two amino acids are necessary for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1. As a positive control, Rac1 was activated by antibody crosslinking of the endogenous VCAM-1 on the cells expressing V/I S730A or V/I S737A (Figure 5F,G), suggesting that transfection has not induced an inherent change within these endothelial cell lines that prevents the cells from activating Rac1. Thus, S730 and S737, but not S728, Y729, or N724 are involved in VCAM-1 activation of Rac1.

The cytoplasmic domain amino acids for VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes are at distinct sites from those for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1

We and others have previously reported that antibody crosslinking of VCAM-1 rapidly activates calcium fluxes 15, 21. The calcium fluxes are required for VCAM-1 activation of NADPH oxidase which is necessary for leukocyte recruitment in vitro and in vivo 7, 26, 36, 37. Therefore, we determined whether the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 is required for VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes using the cells expressing V/I WT or V/I mutants. Crosslinking the V/I WT receptors with an anti-ICAM-1/secondary antibody complex significantly activated a calcium flux as compared to the treatment of the cells with an isotype control (Figure 6). Activation of these cells by crosslinking VCAM-1 with an anti-VCAM-1/secondary antibody complex activated a calcium flux (Figure 6). This rapid activation of a calcium flux by anti-VCAM-1 is similar to our previous report with anti-VCAM-1 activation of calcium in mHEV cells not expressing the V/I chimera 15. In contrast, when we crosslinked the V/I S728A receptors or the V/I Y729A receptors, they failed to activate a calcium response (Figure 6), demonstrating that these two amino acids are necessary for VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes. As a positive control, calcium fluxes were activated by antibody crosslinking of the endogenous VCAM-1 on the cells expressing the V/I S728A receptor or the V/I Y729A receptor (Figure 6), suggesting that transfection has not induced an inherent change within these endothelial cell lines that prevents the cells from activating a calcium flux.

Figure 6. The VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain amino acids S730, and S737 but not S728, Y729, or N724 are necessary for calcium fluxes.

Endothelial cells expressing V/I WT, V/I ΔCD, V/I N724A, V/I S728A, V/I Y729A, V/I S730A, or V/I S737A were loaded with fluo4 and examined for V/I or VCAM-1-induced calcium fluxes. To crosslink and activate the V/I chimeras, anti-ICAM-1, which is specific for domain 1 of ICAM-1, was incubated with a secondary antibody for five minutes and then added to flou4-loaded endothelial cells. Then, relative fluo-4 fluorescence was examined. As a positive control, an anti-VCAM-1 plus a secondary antibody was added to the cells to crosslink and activate the endogenous VCAM-1 for 30 or 60 seconds. Shown are representative calcium fluxes. Also, data from triplicate experiments are presented as the magnitude of the calcium response (peak height; mean± S.E.M.). The other separately derived clone for each V/I chimera had similar results (data not shown). *, p <0.05 compared to isotype control.

Antibody crosslinking of the V/I N724A, V/I S730A, or V/I S737A receptors activated calcium fluxes (Figure 6), suggesting that these three amino acids were not necessary for initiating VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain activation of calcium fluxes. The positive control, antibody crosslinking of the endogenous VCAM-1, activated a calcium flux in the cells expressing V/I N724A, V/I S728A, or V/I Y729F receptors (Figure 6). Thus, S728 and Y729 but not S730, S737, or N724 were involved in VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes, suggesting that S728 and Y729 are at distinct functional sites on the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1.

Molecular model of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain

The structure of the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 is not known. Therefore, the I-TASSER molecular modeling program 32–34 was used to model the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain. All predictions from the I-TASSER modeling for the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain were alpha helical. The VCAM-1 model with the best I-TASSER confidence score is shown from three views rotated on the vertical axis in Figure 7A. There is a horizontal plain containing S728 and Y729 (Figure 7A right panel). Interestingly, on the other side of the helix, S730 and S737 are on a vertical plain in the helix (Figure 7A left panel), suggesting that S730/S737 and S728/Y729 may have different functions in VCAM-1 signaling. This modeling is consistent with the data in Figures 5 & 6 demonstrating that S730/S737 are required for Rac1 signaling but S728/Y729 are required for calcium fluxes. The S728/Y729 and S730/S737 were necessary for VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration, because these amino acids activate calcium fluxes and Rac1, respectively and calcium/Rac1 are each required for VCAM-1 activation of NOX2 during leukocyte transendothelial migration (Figure 7B) 7.

Figure 7. Model of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain structure and function.

A) The VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain 19 amino acid sequence (RKANMKGSYSLVEAQKSKV) was submitted to the I-TASSER database for structural prediction. Shown is the model with the highest predictive accuracy score. The three images show three different side-views rotated on the vertical axis of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain with the membrane proximal region at the top and the carboxyl terminus at the bottom of the image. The serines, tyrosine and asparagine are indicated. The I-TASSER program color coded the amino acids as follows: blue for basic amino acids R and K; grey for A and G; light (lt) blue for polar/uncharged amino acids N and Q; yellow for M; purple for Y; red for acidic amino acid E; amber for S; and green for nonpolar amino acids L and V. The S728 and Y729 are on a horizontal plane and on the opposite side of the helix are located S730 and S737 in a vertical plane. B) Schematic for VCAM-1 signaling. Upon antibody crosslinking of VCAM-1, VCAM-1 S728/Y729 function in the activation of calcium fluxes and VCAM-1 S730/S737 function in the activation of Rac-1. The calcium and Rac1 then activate endothelial cell NOX2. Nox2 catalyzes the production of superoxide that then dismutates to H2O2. VCAM-1 induces the production of only 1 μM H2O2. H2O2 activates endothelial cell-associated matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade extracellular matrix and endothelial cell surface receptors in cell junctions. H2O2 also diffuses through membranes to oxidize and transiently activates endothelial cell protein kinase C-α (PKCα). PKCα phosphorylates and activates protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). PTP1B is not oxidized. PTP1B activates signals that induce phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2. These signals through reactive oxygen species (ROS), MMPs, PKCα, PTP1B, and ERK1/2 are required for VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrated, for the first time, that the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is necessary for VCAM-1-stimulated endothelial cell signaling and leukocyte transendothelial migration. We also demonstrated that two amino acids within the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, S730 and S737, were necessary for VCAM-1 activation of the downstream signal Rac1 and for leukocyte transmigration. In contrast, S728 and Y729 in the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain were not necessary for activation of Rac1 but were required for VCAM-1 activation of calcium fluxes and leukocyte transendothelial migration. Mutation of another nearby amino acid, N724 in the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, did not affect Rac1 activation, calcium fluxes, or leukocyte transendothelial migration, indicating that the loss in leukocyte migration with a mutation in VCAM-1 S728, Y729, S730 or S737 was not a general effect of mutating the cytoplasmic domain. Furthermore, modeling of the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain indicates that the cytoplasmic domain is an alpha-helix with amino acids S728/Y729 located in a plane on one side of the helix and S730/S737 located in a plane on the opposite side of the alpha-helix. The opposing locations on the alpha-helix for these two sets of amino acids suggest that these amino acids have distinct regulatory functions. This model is consistent with our findings that S730/S737 function in the activation of Rac1 for promotion of leukocyte transendothelial migration and that S728/Y729 function in the activation of calcium fluxes in the regulation of leukocyte transendothelial migration.

S728/Y729 and S730/S737 are distinct sites in VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain for signaling; the S728/Y729 mediated activation of calcium fluxes and the S730/S737 mediated activation of Rac1. Calcium and Rac1 function in the translocation of the cytoplasmic subunits of NOX2 to the membrane and activation of the active complex (Figure 7B) in several cell types 38–45. NOX2 is then required for VCAM-1-dependent activation of PKCα, PTP1B, ERK1/2 and VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo (Figure 7B) 7, 22, 24, 35.

Although functions for the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 have not been previously reported, the functions of the cytoplasmic domain of other members of the immunoglobulin superfamily have been studied. Studies of other immunoglobulin superfamily molecules have indicated that cytoplasmic domain phosphorylation regulates signaling, membrane localization, and protein recruitment to the cytoplasmic domain 46–52. Several immunoglobulin superfamily members, including the T cell receptor, B cell receptor, platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), signal through regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation in their immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) or immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif (ITAM). The ITIMs in the cytoplasmic domain of the immunoglobulin superfamily proteins PECAM-1 and BTLA are necessary for initiating a downstream signaling cascade 48, 53. In contrast, ITIM and ITAM are not present in the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, suggesting alternative mechanisms for VCAM-1 signaling. In addition to ITIM regulation of PECAM-1, the PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is regulated by serine phosphorylation 54 and by palmitoylation of cysteine 595 in its cytoplasmic domain 55. In contrast, the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain is not regulated by cysteine palmitoylation because it does not contain a cysteine. PECAM-1 is also reported to contain a 20 amino acid alpha-helix within the 113 amino acid PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain. This PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain alpha-helix only forms upon interaction with the membrane lipid environment 56. We also report a VCAM-1 model with an alpha-helix in the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain. However, there is no sequence homology between the PECAM-1 and VCAM-1 helix, suggesting that there are likely different functions for the helix in these receptors.

The cytoplasmic domain of the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 is necessary for ICAM-1 signaling. Interestingly, two studies examining ICAM-1 in mouse and rat brain endothelium showed that deleting the whole ICAM-1 cytoplasmic domain drastically reduced T cell transendothelial migration and, upon ICAM-1 crosslinking, reduced the activation of RhoGTPase, a downstream mediator of ICAM-1 signaling 57–59. ICAM-1 contains a tyrosine within an ITIM at amino acids 480–488 (60). However, a mutation of the ICAM-1-cytoplasmic tyrosine to a phenylalanine did not affect the downstream activation of the RhoGTPase but it did partially block migration 57. This lack of effect on RhoGTPase with the mutated ICAM-1 tyrosine is similar to our data demonstrating that mutation of VCAM-1 Y729 did not alter activation of Rac1. However, VCAM-1 Y729 mutation blocks calcium fluxes and leukocyte transendothelial migration. In contrast, unlike the ICAM-1 cytoplasmic domain, which does not contain serines and does not have an amino acid(s) identified for activation of RhoGTPase, we demonstrated that S730 and S737 are necessary for VCAM-1 activation of Rac1. It is also reported that the ICAM-1 membrane proximal sequence RKIKK is required for ICAM-1 association with cytoskeletal proteins and is required for leukocyte transendothelial migration 61. An RKIKK sequence is not present in the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 and the ICAM-1 cytoplasmic domain sequence does not have amino acid sequence homology with the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain 57, 58.

Several vascular adhesion molecules that are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily have some amino acid homology among species. For PECAM-1, the mouse and human 113 amino acid cytoplasmic domain sequence has about a 70% identity and within this domain the longest sequence of identity is 8 amino acids. For ICAM-1, the mouse and human 27 amino acid cytoplasmic domain sequence has about a 50% identity and within this domain the longest sequence of identity is the membrane proximal 5 amino acids 57, 58. In contrast, the entire 19 amino acid cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 is 100% identical in amino acid sequence among many mammals including human, mouse, rabbit, rat, chimpanzee, rhesus macaque, sumatran orangutan, common shrew, and microbat. This 100% amino acid identity observed for the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain among species is rare, suggesting a critical role for this domain in function and evolution.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the serines and the tyrosine within the VCAM-1 cytoplasmic domain form distinct sites that are necessary for VCAM-1-stimulated endothelial cell signaling and leukocyte transendothelial migration. VCAM-1 S730 and S737 were required for activation of Rac1 and leukocyte transendothelial migration but not calcium fluxes. VCAM-1 S728 and Y729 were not required for activation of Rac1 but were required for calcium fluxes and leukocyte transendothelial migration. Calcium and Rac1 function together to activate NOX2 and then NOX2 is required for leukocyte transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo (Figure 7B) 26, 36. These results define a functional role for the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1, whereby, in addition to the extracellular domains being involved in leukocyte-endothelial cell binding, there are distinct sites within the cytoplasmic domain of VCAM-1 that actively regulate VCAM-1 signaling during leukocyte recruitment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants [R01 HL69428 (J.M.C-M) and R01 AT004837 (J.M.C-M)] and by American Heart Association Grants [0855583G and 12GRNT12100020 (J.M.C-M)].

Abbreviations

- calcein-AM

calcein acetoxymethyl ester

- ERK1/2

extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- ITAM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif

- ITIM

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif

- MAdCAM

mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- PECAM-1

platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1

- PKCα

protein kinase C alpha

- PTP1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- V/I

VCAM-1 with the first two immunoglobulin-like domains replaced with the first two immunoglobulin-like domains of ICAM-1

- V/I ΔCD

V/I construct with a deletion of the cytoplasmic domain

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author contributions. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alon R, Kassner PD, Carr MW, Finger EB, Hemler ME, Springer TA. The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1243–1253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan BM, Elices MJ, Murphy E, Hemler ME. Adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and fibronectin. Comparison of alpha 4 beta 1 (VLA-4) and alpha 4 beta 7 on the human B cell line JY. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8366–8370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, Crouse C, Luhowskyj S, Hemler ME, Lobb RR. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/Fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90661-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abonia JP, Hallgren J, Jones T, Shi T, Xu Y, Koni P, Flavell RA, Boyce JA, Austen KF, Gurish MF. Alpha-4 integrins and VCAM-1, but not MAdCAM-1, are essential for recruitment of mast cell progenitors to the inflamed lung. Blood. 2006;108:1588–1594. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochner BS, Luscinskas FW, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Newman W, Sterbinsky SA, Derse-Anthony CP, Klunk D, Schleimer RP. Adhesion of human basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils to interleukin 1-activated human vascular endothelial cells: contributions of endothelial cell adhesion molecules. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1553–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyake K, Medina K, Ishihara K, Kimoto M, Auerbach R, Kincade PW. A VCAM-like adhesion molecule on murine bone marrow stromal cells mediates binding of lymphocyte precursors in culture. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:557–565. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook-Mills JM, Marchese M, Abdala-Valencia H. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Expression and Signaling during Disease: Regulation by Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidants. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1607–1638. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin JE, Hatfield CA, Winterrowd GE, Brashler JR, Vonderfecht SL, Fidler SF, Griffin RL, Kolbasa KP, Krzesicki RF, Sly LM, Staite ND, Richards IM. Airway recruitment of leukocytes in mice is dependent on alpha4-integrins and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1997;272:L219–L229. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allavena R, Noy S, Andrews M, Pullen N. CNS Elevation of Vascular and Not Mucosal Addressin Cell Adhesion Molecules in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:556–562. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iiyama K, Hajra L, Iiyama M, Li H, DiChiara M, Medoff BD, Cybulsky MI. Patterns of Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 and Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 Expression in Rabbit and Mouse Atherosclerotic Lesions and at Sites Predisposed to Lesion Formation. Circ Res. 1999;85:199–207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurtner GC, Davis V, Li H, McCoy MJ, Sharpe A, Cybulsky MI. Targeted disruption of the murine VCAM1 gene: essential role of VCAM-1 in chorioallantoic fusion and placentation. Genes Develop. 1995;9:1–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matheny HE, Deem TL, Cook-Mills JM. Lymphocyte migration through monolayers of endothelial cell lines involves VCAM-1 signaling via endothelial cell NADPH oxidase. J Immunol. 2000;164:6550–6559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tudor K-SRS, Hess KL, Cook-Mills JM. Cytokines modulate endothelial cell intracellular signal transduction required for VCAM-1-dependent lymphocyte transendothelial migration. Cytokine. 2001;15:196–211. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deem TL, Cook-Mills JM. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) activation of endothelial cell matrix metalloproteinases: role of reactive oxygen species. Blood. 2004;104:2385–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook-Mills JM, Johnson JD, Deem TL, Ochi A, Wang L, Zheng Y. Calcium mobilization and Rac1 activation are required for VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1) stimulation of NADPH oxidase activity. Biochem J. 2004;378:539–547. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook-Mills JM. Hydrogen peroxide activation of endothelial cell- associated MMPs during VCAM-1-dependent leukocyte migration. Cell Mol Biol. 2006;52:8–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdala-Valencia H, Cook-Mills JM. VCAM-1 signals activate endothelial cell protein kinase Calpha via oxidation. J Immunol. 2006;177:6379–6387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deem TL, Abdala-Valencia H, Cook-Mills JM. VCAM-1 activation of endothelial cell protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J Immunol. 2007;178:3865–3873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Wetering S, van den Berk N, van Buul JD, Mul FP, Lommerse I, Mous R, ten Klooster JP, Zwaginga JJ, Hordijk PL. VCAM-1-mediated Rac signaling controls endothelial cell-cell contacts and leukocyte transmigration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C343–352. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00048.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook-Mills JM. Reactive oxygen species regulation of immune function. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:497–498. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Wetering S, van den Berk N, van Buul JD, Mul FPJ, Lommerse I, Mous R, Klooster J-Pt, Zwaginga J-J, Hordijk PL. VCAM-1-mediated Rac signaling controls endothelial cell-cell contacts and leukocyte transmigration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C343–C352. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00048.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdala-Valencia H, Berdnikovs S, Cook-Mills JM. Mechanisms for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 activation of ERK1/2 during leukocyte transendothelial migration. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook-Mills JM, Gallagher JS, Feldbush TL. Isolation and characterization of high endothelial cell lines derived from mouse lymph nodes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:167–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02723682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deem TL, Abdala-Valencia H, Cook-Mills JM. VCAM-1 Activation of PTP1B in Endothelial Cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3865–3873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook-Mills JM, Gallagher JS, Feldbush TL. Isolation and characterization of high endothelial cell lines derived from mouse lymph nodes. In Vitro Cell Develop Biol. 1996;32:167–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02723682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matheny HE, Deem TL, Cook-Mills JM. Lymphocyte Migration through Monolayers of Endothelial Cell Lines involves VCAM-1 Signaling via Endothelial Cell NADPH Oxidase. J Immunol. 2000;164:6550–6559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qureshi MH, Cook-Mills J, Doherty DE, Garvy BA. TNF-alpha-Dependent ICAM-1- and VCAM-1-Mediated Inflammatory Responses Are Delayed in Neonatal Mice Infected with Pneumocystis carinii. J Immunol. 2003;171:4700–4707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nobis U, Pries AR, Cokelet GR, Gaehtgens P. Radial distribution of white cells during blood flow in small tubes. Microvasc Res. 1985;29:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(85)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith ML, Long DS, Damiano ER, Ley K. Near-wall micro-PIV reveals a hydrodynamically relevant endothelial surface layer in venules in vivo. Biophys J. 2003;85:637–645. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipowsky HH. Microvascular rheology and hemodynamics. Microcirc. 2005;12:5–15. doi: 10.1080/10739680590894966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ager A, Mistry S. Interaction between lymphocytes and cultured high endothelial cells: an in vitro model of lymphocyte migration across high endothelial venule endothelium. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1265–1274. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y. I-TASSER: Fully automated protein structure prediction in CASP8. Protein Struct Func Bioinform. 2009;77:100–113. doi: 10.1002/prot.22588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protocols. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdala-Valencia H, Cook-Mills JM. VCAM-1 Signals Activate Endothelial Cell Protein Kinase Ca Via Oxidation. J Immunol. 2006;177:6379–6387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdala-Valencia H, Earwood J, Bansal S, Jansen M, Babcock G, Garvy B, Wills-Karp M, Cook-Mills JM. Nonhematopoietic NADPH oxidase regulation of lung eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness in experimentally induced asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1111–1125. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00208.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook-Mills JM, Johnson JD, Deem TL, Ochi A, Wang L, Zheng Y. Calcium mobilization and Rac1 activation are required for VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1) stimulation of NADPH oxidase activity. Biochem J. 2004;378:539–547. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lang ML, Kerr MA. Characterization of FcalphaR-triggered Ca(2+) signals: role in neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:749–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McPhail LC, Clayton CC, Snyderman R. The NADPH oxidase of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Evidence for regulation by multiple signals. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Movitz C, Sjolin C, Dahlgren C. A rise in ionized calcium activates the neutrophil NADPH-oxidase but is not sufficient to directly translocate cytosolic p47phox or p67phox to b cytochrome containing membranes. Inflammation. 1997;21:531–540. doi: 10.1023/a:1027363730746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H, Duncan RF, Robison TW, Gao L, Forman HJ. Ca(2+)-dependent p47phox translocation in hydroperoxide modulation of the alveolar macrophage respiratory burst. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L1042–1047. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goodman EB, Tenner AJ. Signal transduction mechanisms of C1q-mediated superoxide production. Evidence for the involvement of temporally distinct staurosporine-insensitive and sensitive pathways. J Immunol. 1992;148:3920–3928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granfeldt D, Samuelsson M, Karlsson A. Capacitative Ca2+ influx and activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst. Different regulation of plasma membrane- and granule-localized NADPH-oxidase. J Leuk Biol. 2002;71:611–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorzalczany Y, Sigal N, Itan M, Lotan O, Pick E. Targeting of Rac1 to the phagocyte membrane is sufficient for the induction of NADPH oxidase assembly. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40073–40081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed S, Prigmore E, Govind S, Veryard C, Kozma R, Wientjes FB, Segal AW, Lim L. Cryptic Rac-binding and p21(Cdc42Hs/Rac)-activated kinase phosphorylation sites of NADPH oxidase component p67(phox) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15693–15701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultheis M, Diestel S, Schmitz B. The Role of Cytoplasmic Serine Residues of the Cell Adhesion Molecule L1 in Neurite Outgrowth, Endocytosis, and Cell Migration. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2007;27:11–31. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9113-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chemnitz JM, Lanfranco AR, Braunstein I, Riley JL. B and T Lymphocyte Attenuator-Mediated Signal Transduction Provides a Potent Inhibitory Signal to Primary Human CD4 T Cells That Can Be Initiated by Multiple Phosphotyrosine Motifs. J Immunol. 2006;176:6603–6614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavrieli M, Watanabe N, Loftin SK, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of B and T lymphocyte attenuator required for association with protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2. Biochem biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Florey O, Durgan J, Muller W. Phosphorylation of Leukocyte PECAM and Its Association with Detergent-Resistant Membranes Regulate Transendothelial Migration. J Immunol. 2010;185:1878–1886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tseng S-Y, Liu M, Dustin ML. CD80 Cytoplasmic Domain Controls Localization of CD28, CTLA-4, and Protein Kinase C θ in the Immunological Synapse. J Immunol. 2005;175:7829–7836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gibson AW, Li X, Wu J, Baskin JG, Raman C, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP. Serine phosphorylation of FcγRI cytoplasmic domain directs lipid raft localization and interaction with protein 4.1G. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:97–103. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0711368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu W, Shy M, Kamholz J, Elferink L, Xu G, Lilien J, Balsamo J. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of P0 reveal a role for PKC-mediated phosphorylation in adhesion and myelination. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:439–446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garnacho C, Shuvaev V, Thomas A, McKenna L, Sun J, Koval M, Albelda S, Muzykantov V, Muro S. RhoA activation and actin reorganization involved in endothelial CAM-mediated endocytosis of anti-PECAM carriers: critical role for tyrosine 686 in the cytoplasmic tail of PECAM-1. Blood. 2008;111:3024–3033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newman PJ, Newman DK. Signal Transduction Pathways Mediated by PECAM-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:953–964. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sardjono CT, Harbour SN, Yip JC, Paddock C, Tridandapani S, Newman PJ, Jackson DE. Palmitoylation at Cys595 is essential for PECAM-1 localisation into membrane microdomains and for efficient PECAM-1-mediated cytoprotection. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:756–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paddock C, Lytle BL, Peterson FC, Holyst T, Newman PJ, Volkman BF, Newman DK. Residues within a lipid-associated segment of the PECAM-1 cytoplasmic domain are susceptible to inducible, sequential phosphorylation. Blood. 2011;117:6012–6023. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyck R, Reiss Y, Gerwin N, Greenwood J, Adamson P, Engelhardt B. T-cell interaction with ICAM-1/ICAM-2 double-deficient brain endothelium in vitro: the cytoplasmic tail of endothelial ICAM-1 is necessary for transendothelial migration of T cells. Blood. 2003;102:3675–3683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenwood J, Amos CL, Walters CE, Couraud P-O, Lyck R, Engelhardt B, Adamson P. Intracellular Domain of Brain Endothelial Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 Is Essential for T Lymphocyte-Mediated Signaling and Migration. J Immunol. 2003;171:2099–2108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Buul JD, Allingham MJ, Samson T, Meller J, Boulter E, Garcia-Mata R, Burridge K. RhoG regulates endothelial apical cup assembly downstream from ICAM1 engagement and is involved in leukocyte trans-endothelial migration. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1279–1293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pazdrak K, Young TW, Stafford S, Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Straub C, Starosta V, Brasier A, Kurosky A. Cross-Talk between ICAM-1 and GM-CSF Receptor Signaling Modulates Eosinophil Survival and Activation. J Immunol. 2008;180:4182–4190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oh HM, Lee S, Na BR, Wee H, Kim SH, Choi SC, Lee KM, Jun CD. RKIKK motif in the intracellular domain is critical for spatial and dynamic organization of ICAM-1: functional implication for the leukocyte adhesion and transmigration. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2322–2335. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]