Abstract

Although drinking motives have been shown to influence drinking behavior among women with trauma histories and PTSD, no known research has examined the influence of drinking motives on alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences for women with PTSD as compared to women with a trauma history but no PTSD and women with no trauma history. Therefore, the present study sought to examine the associations between drinking motives women held for themselves as well as their perception of the drinking motives of others and their own alcohol use and consequences, and whether this was moderated by a history of trauma and/or PTSD. College women (N = 827) were categorized as either having no trauma exposure (n = 105), trauma exposure but no PTSD (n = 580), or PTSD (n = 142). Results of regression analyses revealed that women with trauma exposure and PTSD consume more alcohol and are at greatest risk of experiencing alcohol-related consequences. A diagnosis of PTSD moderated the association between one’s own depression and anxiety coping and conformity drinking motives and alcohol-related consequences. PTSD also moderated the association between the perception of others’ depression coping motives and one’s own consequences. These findings highlight the importance of providing alternative coping strategies to women with PTSD to help reduce their alcohol use and consequences, and also suggest a possible role for the perceptions regarding the reasons other women drink alcohol and one’s own drinking behavior that may have important clinical implications.

Keywords: Trauma Exposure, PTSD, Drinking Motives, Alcohol Use, Alcohol Consequences

1. Introduction

Rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and sexual assault (SA) are high among college women. Approximately 40% of college women reported a history of CSA and 50% reported SA (Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McAuslan, 1996; Bartoi, Kinder, & Tomianovic, 2000; Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987). These rates are concerning, especially given the deleterious consequences associated with a history of CSA and SA, including academic dropout and mental health problems such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Porche, Fortuna, Lin, & Alegria, 2011). Women with a history of trauma and PTSD are also at increased risk for heavy drinking (Corbin, Bernat, Calhoun, McNair, & Seals, 2001; Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997; McFarlane et al., 2009; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009) and report more negative consequences associated with their consumption than their non-trauma exposed peers (Bedard-Gilligan, Kaysen, Desai, & Lee, 2011; Lindgren, Neighbors, Blayney, Mullins, & Kaysen, 2012; Palmer, McMahon, Rounsaville, & Ball, 2010).

1.1 Why People Drink

Motivational models of alcohol use have attempted to explain the reasons why people drink, and suggest that alcohol use is often related to the desired outcome of their use (Cooper, 1994). Accordingly, alcohol consumption can be conceptualized as being motivated by its perceived functions (e.g., coping with negative emotion) and motives are an important proximal predictor of drinking and related consequences (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). Cooper (1994) proposed four classes of drinking motives: social (e.g., “Because it helps you enjoy a party”), coping (e.g., “To forget about your problems”), enhancement (e.g., “Because it gives you a pleasant feeling”), and conformity (e.g., “To be liked”). Recently, coping motives have been further divided into coping with either anxiety or depression (Grant, Stewart, O’Connor, Blackwell, & Conrod, 2007). Drinking motives (especially social and enhancement reasons for drinking) have been linked to college student alcohol use more generally (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Mohr et al., 2005; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003), and have also been associated with drinking among women with a history of trauma and PTSD (e.g., Corbin et al., 2001; Dixon, Leen-Feldner, Ham, Feldner, & Lewis, 2009; Stewart, Mitchell, Wright, & Loba, 2004).

1.1.1 Relationships among drinking motives, trauma, and PTSD

Several studies have shown that women with a history of sexual assault (Corbin et al., 2001; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005), sexual coercion (Fossos, Kaysen, Neighbors, Lindgren, & Hove, 2011), and childhood sexual assault (Ullman et al., 2005) report greater motivation for drinking to cope than women without a history of assault. Furthermore, greater alcohol coping motives have been associated with heavier alcohol consumption in trauma-exposed populations (Fossos et al., 2011; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Schuck & Widom, 2001; Ullman et al., 2005). This relationship is often explained by the self-medication hypothesis whereby alcohol use is thought to be an avoidant coping strategy that functions to relieve distress associated with experiencing a traumatic event (Saladin, Brady, Dansky, & Kilpatrick, 1995). In further support of this theory, it has been found that greater levels of PTSD symptoms are associated with greater alcohol use coping motives (Dixon et al., 2009; Stewart et al., 2004).

Sexual assault can lead to numerous negative outcomes in addition to PTSD (e.g., Cloitre, Miranda, Stovall-McClough, & Han, 2005; Miranda, Meyerson, Long, Marx, & Simpson, 2002), including increased depressive symptoms and general distress. Both depressive symptoms and general distress have also been found to predict increased alcohol coping motives (Cooper et al., 1995; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). Although we would expect that individuals with PTSD are at greatest risk to use alcohol to cope with negative emotions, it may be that trauma exposure is associated with increased coping motives, given that being exposed to traumatic events predicts increased depressive symptoms and distress in college students (e.g., Kaltman, 2005; Krupnik et al., 2004). Related, there is some evidence that women with assault histories are more likely to report positive enhancement motives for their drinking behavior (Harrison, Fulkerson, & Beebe, 1997) and that enhancement motives help explain the relationship between CSA and drinking problems (Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). This suggests that in addition to drinking to cope, women with an assault history may also drink to increase positive affect. Conformity and social motives have also been associated with college students’ drinking although little is known about whether these motives are associated with drinking and alcohol-related consequences among individuals with trauma exposure and/or PTSD (Cronin, 1997; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2001).

To our knowledge no studies have examined the impact of PTSD itself versus trauma exposure on the influence of drinking motives on alcohol use and consequences for women. These investigations are necessary to better elucidate whether it is PTSD that is related to increased alcohol use coping motives or whether it is sexual assault exposure in and of itself. This is a particularly relevant question for female college students, a population for which rates of sexual victimization and alcohol misuse are alarmingly high. Understanding which women are at highest risk for drinking to cope with distress is crucial to inform and establish prevention and intervention efforts.

1.2 Perceptions of Why Others Drink

There has been also been considerable research documenting the influence of social norms on alcohol use among young adults (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007). Both descriptive (i.e., the perception on how much or how often others engage in a certain behavior, Cialdini, Reno & Kallgren, 1990) and injunctive norms (i.e., the perceived attitudes or moral rules others have regarding a certain behavior, Cialdini et al., 1990) have been found to be highly influential on one’s own personal behavior (Neighbors et al., 2007). College students typically overestimate the prevalence and approval of alcohol use among their peers and these discrepancies are associated with greater personal drinking and alcohol-related consequences (e.g., Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991; Borsari & Carey, 2000; 2003; Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Lewis and Neighbors, 2004). These self-other comparisons have been found to be important targets of intervention, with numerous studies showing that correcting misperceptions of peer drinking to mediate intervention efficacy resulting in lower alcohol use (e.g., Borsari and Carey, 2000; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004).

Recent research has broadened the field by documenting that misperceptions exist for the experience of alcohol related-consequences (Baer & Carney, 1993; Larimer et al., 2004; Lee, Geisner, Patrick, & Neighbors, 2010), drinking in different locations and contexts (Lewis et al., 2011), and engagement in protective behavioral strategies (Lewis, Rees, & Lee, 2009). The social norms literature often references Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1969; 1977) as support for the influence of social norms which suggests that one’s behavior is modeled after perceptions of others’ behavior. Studies also suggest that one’s own behavior can influence the way in which they perceive the behavior of their peers (Stappenbeck, Quinn, Wetherill, & Fromme, 2010). For example, individuals who drink more heavily may be more likely to perceive their peers as being heavier drinkers. Thus, it makes sense to reason that individuals may hold beliefs about their peer’s motivations for drinking alcohol and that these beliefs may be influenced by personal characteristics.

The present study aims to extend the social norms literature further by examining the perceived motivations of others for drinking alcohol. Of particular interest, we will explore whether these relationships may be similar or different for individuals with a trauma history or PTSD versus those with no history of trauma. It may be that individuals with PTSD who report greater drinking motives perceive that others also drink for similar reasons, which in turn can be associated with greater alcohol use and consequences.

1.3 Present Study

The present study sought to examine the effects of trauma exposure and PTSD on the association between drinking motives and drinking behavior. First we examined whether or not a history of trauma and/or PTSD moderated the associations between one’s own drinking motives and alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. We hypothesized that individuals who held stronger drinking motives would report greater alcohol use and consequences. Consistent with the self-medication hypothesis, we expected that the association between drinking motives and alcohol use and consequences would be stronger for women with PTSD compared to those with a history of trauma and no PTSD and those with no trauma history. We also examined whether perceptions of other’s drinking motives influenced one’s own alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences, and whether trauma history and PTSD moderated this association. Based on the general social norms literature, we hypothesized that women who perceived that others held stronger drinking motives would themselves drink more and experience more alcohol-related consequences, and that this would be more pronounced for those with PTSD compared to those with a history of trauma and no PTSD and those with no trauma history.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Participants for the present study included 827 undergraduate college women who participated in a screening and baseline survey for a larger study on daily assessment of post-traumatic stress and alcohol use at a large public west-coast university. Approximately 11,500 undergraduate women were randomly selected from the university’s registrar’s list over the course of two years and contacted via email and US mail to complete an online screening questionnaire to determine eligibility for the larger daily assessment study (described in Naragon-Gainey, Simpson, Moore, Varra, & Kaysen, 2012).

Over 4200 women completed the screening survey (36.8%). Eligibility criteria for the larger study included reporting drinking four drinks or more on one occasion at least two times in the past month AND reporting trauma exposure (i.e., having at least one incidence of adult sexual assault [not within the previous three months] or childhood sexual abuse). Further, a smaller random subset of participants meeting drinking criteria and with no history of any DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) PTSD Criterion A traumatic events were invited to the study. Of those who completed screening, 860 were recruited to complete an online baseline measure and 793 completed the baseline measure. An additional 34 students had partial data and were included in the present analyses.

Demographic characteristics of the final sample (N = 827) included 70.5% White, 16.6% Asian, and 12.9% other. The average age of the sample was 20.4 years (SD = 1.8). At the time participants completed the screening, 17.5% were freshmen, 21.6% were sophomores, 26.8% were juniors, 25.6% were seniors, and 8.3% reported being in their 5th year of college or more.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Screening criteria and group definitions

Trauma Exposure status was determined by endorsement of any of seventeen lifetime Criterion A (i.e., extreme traumatic stressors; APA, 1994) events using the modified version of the Traumatic Life Experiences Questionnaire. Participants were asked how many times they experienced each event, ranging from 0= no, never to 5= more than 5 times. Additional sub-questions regarding experience of fear, horror, helplessness, or physical injury were asked for any events being endorsed one or more times.

Adulthood Sexual Assault (ASA) was assessed by the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Gidycz, 1985; Koss & Oros, 1982) and defined as “unwanted oral-genital contact, vaginal/anal intercourse, and/or penetration by objects since the age of 14.” Sexual victimization included attempted and completed unwanted oral, vaginal, and anal sexual intercourse. Response options for each experience were presented as 1= yes and 0= no. The experiences positively endorsed were summed for a total number of ASA incidents.

Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA) was assessed with the Childhood Victimization Questionnaire (CVQ; Finkelhor, 1979) and used to index victimization before the age of 14. Childhood sexual abuse was defined as “any sexual activity that seemed coercive or forced and occurred before the age of 14 with someone 5 or more years older.” Participants were presented a list of eleven unwanted sexual experiences, ranging from a sexual invitation to intercourse, and were asked which, if any, had happened to them, from 1= yes and 0= no. For each unwanted sexual experience reported, participants were asked how many times it occurred, from 1= 1 time to 4= 8 or more times. Distress was also assessed with response options ranging from 1= not at all upsetting to 6= extremely upsetting. The number of times each experience occurred was summed for a total number of CSA incidents.

PTSD Symptomatology was assessed using the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS;;Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997). Women in the trauma condition were asked to focus on their worst unwanted sexual experience while women in the no trauma condition were asked to focus on a stressful life event when responding to the PDS. Participants reported how much each PTSD symptom had bothered them in the last month on a Likert scale of 0= not at all to 3= very much. PTSD diagnostic status was assigned based on meeting criteria B (1 intrusive symptom), C (3 avoidance symptoms), and D (2 hyperarousal symptoms) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV; APA, 1994). Twenty percent of the women who experienced childhood or adult sexual victimization met these criteria for PTSD.

2.2.2 Alcohol-related measures

Alcohol use (total drinks per week) was assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants were asked to report the number of standard drinks they drank on each day of a typical week in the last three months. A total drinks per week score was computed by summing the number of drinks reported for each day of the typical week.

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). Participants were asked to indicate the number of times they had experienced 23 consequences resulting from alcohol use in the last six months. Two additional items were added regarding driving after drinking. Responses ranged from 0 = never to 4 = more than 10 times. A total RAPI score was computed by summing all responses on the 25 items.

Drinking motives for self was assessed with the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R; Grant et al., 2007), a modified version of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (Cooper, 1994). Participants were presented with 28 items and asked to indicate how often they drank alcohol for each of those reasons, from 1 = never/almost never to 5 = almost always/always. Items are broken down into five motives for drinking including: Depression Coping (9 items, α = .92), Anxiety Coping (4 items, α = .73), Social (5 items, α = .85), Conformity (5 items, α = .85), and Enhancement reasons (5 items, α = .80). Scores for each motive was computed by averaging items within subscale.

Drinking motives for others was assessed by adapting five items matching drinking motives for self to examine the perceived norm for drinking motivations. To reduce participant burden, only selected items representing each of the drinking motives were utilized. Items were selected based on factor loadings within each motive subscale. Participants were asked to indicate “how often you think the typical female college student drinks for each of the following reasons”: To forget worries (Depression Coping), Because it makes them feel confident or more sure of themselves (Anxiety Coping), Because it improves parties and celebrations (Social), To be liked (Conformity) and Because it gives them a pleasant feeling (Enhancement). Response options were the same as the drinking motives for self.

2.3 Data Analytic Plan

In order to examine differences among women without a history of trauma, with a history of trauma but no PTSD, and PTSD, dummy variables were first created with no trauma as the reference condition. Two separate regression models were conducted to examine the main effects of trauma and PTSD compared to no trauma and one’s own drinking motives as well as the interactions between trauma/PTSD status and drinking motives on alcohol use and alcohol consequences. Two separate regression models were also conducted to examine the main effects of trauma and PTSD compared to no trauma and drinking motives for others as well as their interactions on alcohol use and alcohol consequences. All non-significant interaction terms were removed and analyses rerun to create the final trimmed models presented in the tables. Because we were also interested in examining differences between those with a history of trauma but no PTSD and those with PTSD, another set of dummy variables was created with PTSD group as the reference condition. These variables were entered in to the regression models and four additional regression analyses were run identical to those described above. For regression models examining predictors of weekly alcohol consumption, a negative binomial distribution with a log link function was used given that this variable represents count data with positive skew and we report unstandardized regression coefficients and incidence rate ratios (IRRs). A normal distribution was modeled for regressions predicting alcohol-related consequences and we report unstandardized regression coefficients.

3. Results

Of the final sample, 105 (12.7%) women had no trauma exposure, 580 (70.1%) reported trauma exposure but did not meet criteria for PTSD, and 142 (17.2%) met criteria for PTSD. Women with trauma history had an average of 2.46 (SD = 2.08) Criterion A events, and those with PTSD had an average of 4.27 (SD = 2.57) Criterion A events. Means and standard deviations for number of CSA and ASA incidents, alcohol use, alcohol consequences, and drinking motives for self and others are presented in Table 1. Women with PTSD reported more incidents of CSA and ASA as well as greater weekly alcohol consumption and more alcohol-related consequences than women without PTSD. Compared to women with no trauma history, those with a trauma history and no PTSD reported more alcohol consequences; however, their weekly alcohol consumption did not significantly differ. Women with PTSD reported greater rates of drinking to cope with depression and anxiety, as well as drinking for social and conformity reasons compared to those without PTSD, and women with trauma and no PTSD were more likely to drink to cope with depression and anxiety than those without a trauma history. There were no differences on drinking for enhancement motives, suggesting that college women are equally likely to drink for enhancement purposes regardless of their trauma history and PTSD symptoms. Few differences emerged in regards to the perceptions of the drinking motives of others: women with PTSD perceived that others drank more to cope with depression and for conformity purposes than women without PTSD. Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations among alcohol use, consequences, and drinking motives for self and others.

Table 1.

Means (and SDs) of Alcohol Consumption, Consequences, and Drinking Motives for Self and Others by Trauma History and PTSD Diagnosis

| No Trauma (n = 105) |

Trauma no PTSD (n = 580) |

PTSD (n = 142) |

Total Sample (N = 827) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of CSA incidents | -- | 1.63 (4.93)a | 4.74 (7.83)b | 1.96 (5.42) |

| Number of ASA incidents | -- | 2.22 (1.91)a | 4.08 (3.34)b | 2.26 (2.39) |

| Total drinks per week | 9.97 (4.98)a | 11.02 (7.22)a | 12.83 (9.28)b | 11.21 (7.43) |

| RAPI total score | 2.60 (3.06)a | 4.76 (5.54)b | 10.45 (10.99)c | 5.47 (7.00) |

| Drinking motives – self | ||||

| Depression coping | 12.34 (5.25)a | 13.87 (5.62)b | 18.39 (8.73)c | 14.45 (6.48) |

| Anxiety coping | 7.70 (3.03)a | 8.57 (3.13)b | 10.35 (3.93)c | 8.77 (3.35) |

| Enhancement | 15.96 (4.29)a | 16.43 (4.26)a | 16.38 (4.53)a | 16.36 (4.31) |

| Social | 17.38 (4.40)a | 17.83 (4.25)a | 18.63 (4.32)b | 17.90 (4.28) |

| Conformity | 7.02 (2.86)a | 7.56 (3.25)a | 9.21 (4.22)b | 7.77 (3.44) |

| Drinking motives – others | ||||

| Depression coping | 2.11 (0.86)a | 2.24 (0.80)a | 2.53 (0.99)b | 2.27 (0.85) |

| Anxiety coping | 3.56 (1.09)a | 3.72 (1.05)a | 3.81 (1.06)a | 3.71 (1.06) |

| Enhancement | 3.81 (1.00)a | 3.82 (0.99)a | 3.75 (1.01)a | 3.80 (1.00) |

| Social | 4.21 (0.89)a | 4.33 (0.79)a | 4.23 (0.86)a | 4.29 (0.82) |

| Conformity | 3.13 (1.23)a | 3.24 (1.15)a | 3.60 (1.09)b | 3.28 (1.16) |

Note. SD = standard deviation; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CSA = childhood sexual abuse; ASA = adult sexual assault; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Means with different subscripts are significant different (p < .05).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 1 2. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dep -C self |

- | |||||||||||

| 2. Anx -C self |

.676*** | - | ||||||||||

| 3. Enh self |

.232*** | .394*** | - | |||||||||

| 4. Soci al self |

.208*** | .426*** | .549*** | - | ||||||||

| 5. Con self |

.433*** | .432*** | .188*** | .390*** | - | |||||||

| 6. Dep -C othe rs |

.455*** | .361*** | .141*** | .173*** | .316*** | - | ||||||

| 7. Anx -C othe rs |

.242*** | .409*** | .326*** | .362*** | .243*** | .274*** | - | |||||

| 8. Enh othe rs |

.079* | .187*** | .505*** | .320*** | .102** | .191*** | .328*** | - | ||||

| 9. Soci al othe rs |

.087* | .200*** | .356*** | .531*** | .162*** | .185*** | .494*** | .489*** | - | |||

| 10. Con othe rs |

.259*** | .278*** | .159*** | .271*** | .411*** | .317*** | .615*** | .213*** | .384*** | - | ||

| 11. Tota l drin ks |

.193*** | .196*** | .296*** | .177*** | −0.20 | .090* | .117** | .049 | .044 | .02 7 |

- | |

| 12. RA PI scor e |

.430*** | .292*** | .179*** | .129*** | .191*** | .155*** | .067 | .063 | .043 | .08 1* |

.439*** | - |

Note. Dep-C = depression coping; Anx-C = anxiety coping; Enh = enhancement; Con = conformity; RAPI = Rutgers alcohol problem index.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

3.1 Drinking Motives for Self

We first ran the full model predicting alcohol use, Likelihood Ratio (LR) χ2 (19) = 144.80, McFadden’s pseudo R2 = .03. There was a significant interaction between enhancement motives and PTSD compared to no trauma predicting alcohol use, b = 0.04, p < .05, however, this interaction is no longer significant in the final trimmed model, LR χ2 (11) = 138.79, McFadden’s pseudo R2 = .03. As shown in Table 3, there were significant main effects of the number of ASA incidents, b = 0.03, p < .001, depression coping, b = 0.01, p < .01, enhancement motives, b = 0.04, p < .001, social motives, b = 0.01, p < .05, and conformity motives, b = −0.04, p < .001. Women with more incidents of ASA, those with greater depression coping, enhancement, and social motives, and those with weaker conformity motives consumed more alcohol.

Table 3.

Effects of Trauma/PTSD Status and Drinking Motives for Self on Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol Consequences

| Alcohol Use n = 811 |

Alcohol Consequences n = 793 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | IRR [95% C.I.] | b | [95% C.I.] | |

| Number of CSA incidents | 0.00 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.00] | 0.00 | [−0.08, 0.08] |

| Number of ASA incidents | 0.03*** | 1.03 [1.01, 1.05] | 0.53*** | [0.34, 0.73] |

| Trauma no PTSD | −0.04 | 0.96 [0.92, 1.02] | −0.62 | [−4.44, 3.19] |

| PTSD | 0.04 | 1.04 [0.98, 1.09] | −0.94 | [−5.48, 3.60] |

| Drinking motives – self | ||||

| Depression coping | 0.01** | 1.01 [1.01, 1.02] | 0.29* | [0.01, 0.57] |

| Anxiety coping | 0.00 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.02] | 0.04 | [−0.44, 0.53] |

| Enhancement | 0.04*** | 1.04 [1.02, 1.05] | 0.13* | [0.01, 0.24] |

| Social | 0.01* | 1.01 [1.00, 1.03] | −0.01 | [−0.13, 0.12] |

| Conformity | −0.04*** | 0.96 [0.95, 0.98] | −0.32 | [−0.79, 0.15] |

| Trauma × depression coping | -- | -- | −0.04 | [−0.34, 0.26] |

| PTSD × depression coping | -- | -- | 0.38* | [0.05, 0.70] |

| Trauma × anxiety coping | -- | -- | 0.01 | [−0.51, 0.54] |

| PTSD × anxiety coping | -- | -- | −0.72* | [−1.32, −0.11] |

| Trauma × enhancement | 0.02 | 1.01 [0.99, 1.05] | -- | -- |

| PTSD × enhancement | 0.02 | 1.02 [0.99, 1.05] | -- | -- |

| Trauma × conformity | -- | -- | 0.21 | [−0.28, 0.71] |

| PTSD × conformity | -- | -- | 0.63* | [0.10, 1.17] |

Note. Models reflect the final trimmed models including only the significant interactions from the full model (not shown). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; C.I. = confidence interval. Trauma/PTSD status reference condition is no trauma.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

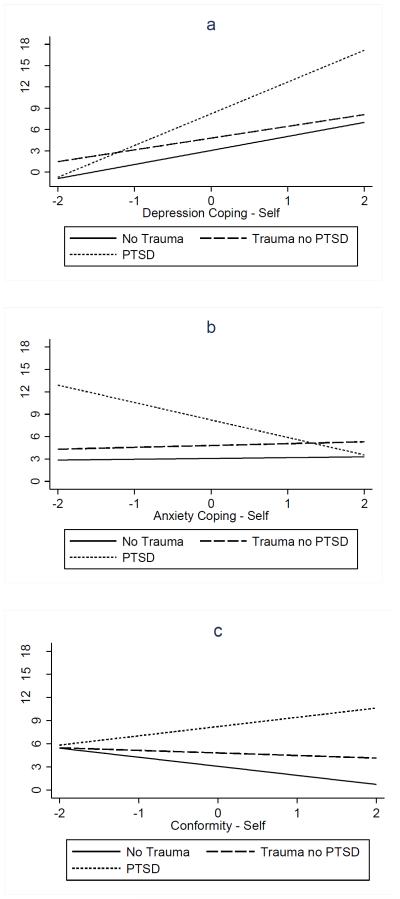

Next, we ran a full model including all parameters predicting alcohol consequences, F(17) = 18.16, p < .001, R2 = .29. After removing the non-significant pairs of interactions, F(15) = 23.32, p < .001, R2 = .31, there were three significant interactions shown in Table 3: (a) depression coping and PTSD compared to no trauma, (b) anxiety coping and PTSD compared to no trauma, and (c) conformity and PTSD compared to no trauma. As shown in Figure 1a, women with PTSD report greater alcohol consequences as their drinking to cope with depression increased compared to women with no trauma and those with trauma but no PTSD, b = −0.38, p < .05. The alcohol-related consequences reported by women with PTSD decreased as their drinking to cope with anxiety increased compared to women with no trauma, and those with trauma but no PTSD (b = −0.72, p < .05; Figure 1b). Additionally, women with PTSD reported more alcohol-related consequences as their conformity drinking motives increased compared to women with no trauma and those with trauma and no PTSD (b = 0.63, p < .05; Figure 1c). There were also significant main effects of the number of ASA incidents reported, b = 0.53, p < .001, as well as enhancement motives, b = 0.13, p < .05, such that women with more incidents of ASA and greater enhancement motives reported more alcohol consequences.

Figure 1.

PTSD diagnosis moderates the effects of: (a) depression coping, (b) anxiety coping, and (c) conformity on alcohol-related consequences.

3.2 Drinking Motives for Others

There were no significant interactions of trauma history or PTSD and the perceptions of the drinking motives of others on weekly alcohol use in the full model, LR χ2 (19) = 56.04, McFadden’s pseudo R2 = .01. After the interactions were removed in the final model, LR χ2 (9) = 49.09, McFadden’s pseudo R2 = .01, there were significant main effects of the number of ASA incidents, b = 0.04, p < .001, anxiety coping, b = 0.01, p < .001, and conformity, b = −0.06, p < .05. See Table 4. Women with more incidents of ASA and who perceived others as having greater anxiety coping motives and weaker conformity motives consumed more alcohol themselves.

Table 4.

Effects of Trauma/PTSD Status and Drinking Motives for Others on Alcohol Consumption and Alcohol Consequences

| Alcohol Use n = 819 |

Alcohol Consequences n = 793 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | IRR [95% C.I.] | b | [95% C.I.] | |

| Number of CSA incidents | 0.00 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.01] | 0.04 | [−0.04, 0.13] |

| Number of ASA incidents | 0.04 | 1.04 [1.02, 1.06] | 0.71*** | [0.50, 0.92] |

| Trauma no PTSD | −0.03 | 0.97 [0.92, 1.02] | −0.41 | [−4.11, 3.29] |

| PTSD | 0.03 | 1.03 [0.98, 1.09] | −2.75 | [−7.25, 1.74] |

| Drinking motives – others | ||||

| Depression coping | 0.04 | 1.04 [0.98, 1.09] | −0.28 | [−1.75, 1.18] |

| Anxiety coping | 0.10*** | 1.11 [1.05, 1.17] | 0.00 | [−0.57, 0.58] |

| Enhancement | 0.01 | 1.01 [0.96, 1.06] | 0.22 | [−0.30, 0.74] |

| Social | −0.02 | 0.98 [0.92, 1.05] | 0.16 | [−0.53, 0.85] |

| Conformity | −0.06* | 0.94 [0.90, 0.99] | 0.03 | [−0.47, 0.53] |

| Trauma × depression coping | 0.42 | [−1.17, 2.01] | ||

| PTSD × depression coping | 2.99** | [1.19, 4.78] | ||

Note. Models reflect the final trimmed models including only the significant interactions from the full model (not shown). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; C.I. = confidence interval. Trauma/PTSD status reference condition is no trauma.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

There was a significant interaction between depression coping and PTSD compared to no trauma predicting alcohol-related consequences in the full model, F(17) = 8.57, p < .001, R2 = .16. The final trimmed model is shown in Table 4, F(11) = 17.62, p < .001, R2 = .20. As shown in Figure 2, women with PTSD reported more alcohol-related consequences as their use of depression coping increased compared to all other women. There was also a significant main effect of the number of ASA incidents, b = 0.71, p < .001; women with more incidents of ASA reported more alcohol-related consequences.

Figure 2.

Depression coping for others is moderated by PTSD diagnosis to predict alcohol consequences.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the influence of one’s own drinking motives as well as the perceived drinking motives of others on alcohol use and consequences among women with no trauma history, those with a trauma history but no PTSD, and women with PTSD. We first examined differences among these women on alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences and found that women with PTSD reported greater alcohol use and consequences than women without PTSD. Notably, women with PTSD reported more than two times the number of consequences than women with a history of trauma but no PTSD. Extant research suggests that a history of sexual assault is associated with myriad negative consequences (e.g., Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 1997; McFarlane et al., 2009; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Porche et al., 2011), however, current findings suggest that it is both sexual assault history and PTSD that may confer added risk for higher alcohol-related consequences. For women with sexual assault histories who do not meet criteria for PTSD, these added risks of alcohol consequences may exist even when they are drinking similar amounts of alcohol as non-assaulted college women.

This study is one of the few to examine differences in reasons for drinking among women based on trauma exposure and PTSD symptomatology. Generally we found that PTSD was associated with endorsing more reasons for drinking, across almost all domains. Women with PTSD reported greater rates of drinking to cope with depression and anxiety, as well as drinking for social and conformity reasons compared to those without PTSD, and women with trauma and no PTSD were more likely to drink to cope with depression and anxiety than those without a trauma history. In terms of women’s perceptions of the drinking motives of others, those with PTSD perceived others as drinking more to cope with depression and to conform than women without PTSD.

Based on a self-medication hypothesis, we anticipated that PTSD would be associated with higher alcohol use and consequences, to the extent to which individuals believe that alcohol is a means by which to manage affect or handle distress. We examined the extent to which a history of trauma and/or PTSD moderated the associations between one’s own drinking motives and alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. Trauma and/or PTSD did not moderate the associations between one’s own drinking motives and alcohol use, suggesting that women were equally likely to drink in response to these motives regardless of their PTSD status or trauma histories. As with previous examinations of college student drinking (Kuntsche et al., 2005; Mohr et al., 2005; Read et al., 2003), we also found that greater depression coping, enhancement, and social motives for drinking were associated with more alcohol consumption among all women.

Consistent with study hypotheses, PTSD significantly moderated the association between depression coping, anxiety coping, and conformity drinking motives and alcohol-related consequences, although not overall amount of alcohol consumption. As predicted by the self-medication hypothesis, as depression coping and conformity increased, the number of consequences increased among women with PTSD relative to women with trauma but not PTSD and those without trauma. These findings suggest that women with PTSD who are motivated to drink to cope with symptoms of depression or to conform are perhaps more likely to drink in situations or in ways that lead to greater consequences of their use even though they are not necessarily consuming more alcohol overall. For example, a woman with PTSD who is motivated to drink to conform may drink the night before she has an early morning class or work and may be more likely to miss class or be late for work. She may also drink more quickly and reach a higher blood alcohol concentration, thereby leading to increased consequences of use. Past studies have found that drinking to cope is associated with greater alcohol consumption and greater negative consequences (Read et al., 2003; Park & Levenson, 2002). In addition, conformity motives, or drinking to fit into a social or peer group is likely associated with heavy episodic, or binge, drinking. Given the known problem of heavy drinking in college students and its relationship to greater negative consequences (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000; Wechsler, Molnar, Davenport, & Baer, 1999), these findings speak to the particular relevance of this issue to college women with PTSD. Conformity motives are associated with increased negative consequences for female college students with social anxiety (e.g., Norberg, Norton, Oliver, & Zvolensky, 2010), and similarly women with assault-related PTSD might show a greater relationship between conformity motives and alcohol related negative consequences due to increased anxiety in social situations.

Contrary to our hypotheses, there was a significant decrease in consequences as anxiety coping motives increased among women with PTSD compared to those without PTSD. Although this finding is a bit surprising, it is possible that this might be due to the fact that women who endorse being motivated to drink to cope with anxiety may avoid going to large parties or crowded bars, which are known high risk environments for college women who are drinking (Armstrong, Hamilton, & Sweeney, 2006; Parks & Miller, 1997; Schwartz & Pitts, 1995). Therefore, these women may be more likely to drink alone or around smaller groups of people which may decrease the likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related consequences. Given that a central symptom of PTSD is the avoidance of situations that may serve as reminders of their traumatic experiences, it seems likely that an anxious avoidant motive for drinking would be particularly relevant for these women. This avoidance may then serve a protective function in terms of alcohol-related consequences. The possible differential role of depression and anxiety coping motives on alcohol consequences may also highlight different influences of anxiety and depression more generally and should be examined further in future studies. If this finding is replicated, it also highlights the importance of examining the context in which drinking takes place to determine how the drinking context may be related to not only alcohol consequences but also sexual assault risk. There was no moderating effect of PTSD or trauma exposure on the association between enhancement and social motives on consequences, suggesting that these two factors did not differentially impact women with versus without PTSD. Thus, overall these results highlight both similarities and differences in drinking motives for women with and without trauma exposure and PTSD.

The current study represented an initial examination of the influence of one’s perceptions of others’ drinking motives on their own alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences. Women who perceived others as having greater anxiety coping motives and weaker conformity motives consumed more alcohol themselves. Additionally, PTSD moderated the association between the perceived use of depression coping motives by others and one’s own alcohol consequences. The more a woman with PTSD perceives that other women consumed alcohol to cope with depression, the more alcohol-related consequences she reported relative to women without PTSD. As described earlier, women with PTSD who reported stronger depression coping drinking motives experienced more alcohol-related consequences, so these women may be more likely to project their own drinking behaviors on to members of her peer group. Additionally, PTSD can result in an increased tendency to see the world through a negative lens (Brewin & Holmes, 2003; Cahill & Foa, 2007), which may increase the extent to which women with PTSD believe that others are also struggling with depressive symptoms and turning to alcohol to cope with distress.

Women who have experienced sexual victimization are at increased risk for revictimization and, especially, for alcohol-related sexual revictimization. These findings may help to explain relationships between PTSD, drinking motives, and alcohol consequences, in ways that may provide increased avenues for intervention. Providing alternative means of coping with psychological distress for those women with PTSD may help to reduce drinking related consequences. These findings suggest that addressing factors such as emotional dysregulation and providing alternative strategies for self-soothing are means that may be especially advantageous for college aged women with PTSD. These findings also indicate that addressing the perceptions regarding the reasons other women drink, particularly related to coping, may be an additional factor to address clinically. Additionally, these findings suggest that providing drink refusal skills and addressing concerns about fitting in are also of import for this population. The majority of brief interventions for preventing college student drinking have focused on normative social influences, social motives for drinking and positive social expectancies more so than on coping motivated drinking. Based on these findings interventions that address other factors in addition to more traditional points of intervention is of special import for college women with PTSD, and could potentially reduce both drinking consequences and, possibly, reduce risk of alcohol-related revictimization.

Limitations of the present research include the fact that data were cross-sectional and based on self-report. The sample was limited to women in college who endorsed a recent heavy drinking episode and for those with a history of trauma, had experienced either child or adult sexual assault. Therefore, these findings may not generalize to men, those who do not drink alcohol or binge drink, those not in college, or individuals who experienced a trauma other than sexual assault. Moreover, the study was predominantly Caucasian and findings may not generalize to other ethnic or cultural groups as they may differ both in terms of degree of vulnerability to PTSD and drinking behavior. Little research to date has examined ethnic and cultural differences in relationships between PTSD and drinking (Nguyen, Kaysen, Dillworth, Brajcich, & Larimer, 2010). Additionally, it should be noted that this sample was relatively high functioning compared to other samples of trauma survivors in the general population given that these women were admitted and maintained enrollment at a well-respected university with a competitive admissions process. The present study represents the first known investigation of perceived drinking motives of others on one’s own drinking and alcohol-related consequences and was assessed in reference to the typical female college student. Research from the social norms literature regarding perceptions of others’ drinking quantity suggests that individuals may be influenced to a greater extent by the perceived behavior of individuals in their own social group rather than the typical college student with whom they may be less likely to identify (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Although it is unclear whether this same distinction would be present with regard to one’s perception of others’ drinking motives, this may help explain the limited role these perceptions had on the women’s drinking and consequences in the current investigation. Future research is needed to explore these and other possible explanations.

4.1 Conclusions

In conclusion, women with a history of trauma who develop PTSD are a particularly vulnerable group beyond those with trauma exposure alone. Although studies suggest that trauma exposure increases one’s reliance on alcohol use to cope with distress, for example, these data suggest that women with PTSD are even more likely to report being motivated to drink in order to cope with symptoms of depression and anxiety. This may explain, in part, the fact that women with PTSD drank more and experienced more alcohol-related consequences than women without PTSD. In accordance with the self-medication hypothesis, these results highlight the fact that women with PTSD may experience greater distress than those with trauma histories who did not develop PTSD, and therefore they drink more to cope with the increased distress. Present results also suggest that women with PTSD may be impacted by their perception of the drinking motives of others. Although more research is needed, these results offer promising directions for intervention efforts.

Highlights.

Women with trauma exposure that go on to develop PTSD consume more alcohol and are at greatest risk of experiencing alcohol-related consequences.

A diagnosis of PTSD moderated the association between one’s own depression and anxiety coping and conformity drinking motives and alcohol-related consequences.

PTSD also moderated the association between the perception of others’ depression coping motives and one’s own consequences.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21AA016211 [PI: Kaysen]; T32AA007455 [PI: Larimer]; F32AA18609 [PI: Bedard-Gilligan). NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors Cynthia A. Stappenbeck, Michele Bedard-Gilligan, Christine M. Lee, and Debra Kaysen have each contributed significantly to, and approve of this final manuscript. All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the current manuscript. Dr. Stappenbeck performed all analyses and contributed largely to writing the Introduction, Results, and Discussion, and created the tables and figures. Dr. Bedard-Gilligan contributed to writing the Introduction and Discussion. Dr. Lee contributed to writing the Introduction and Method, and generated the idea to assess perceptions of others’ drinking motives. Dr. Kaysen generated the idea for the overarching study, developed the measure of others’ drinking motives, oversaw its production, contributed to writing the Discussion, and edited all sections.

Conflict of interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbey A, Ross LT, McDuffie D, McAuslan P. Alcohol and dating risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:147–169. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00669.x. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EA, Hamilton L, Sweeney B. Sexual assault on campus: A multilevel, integrative approach to party rape. Social Problems. 2006;53:483–499. doi:10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.483. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Carney MM. Biases in the perceptions of the consequences of alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Principles of Behavior Modification. Holt, Rinehart & Winston; New York, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoi MG, Kinder BN, Tomianovic D. Interaction effects of emotional status and sexual abuse on adult sexuality. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26:1–23. doi: 10.1080/009262300278614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard-Gilligan M, Kaysen D, Desai S, Lee CM. Alcohol-involved assault: Associations with posttrauma alcohol use, consequences, and expectancies. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. doi:10.1080/07448480309596343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:339–376. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00033-3. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Foa EB. Psychological theories of PTSD. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. Guildford Press; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.58.6.1015. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough C, Han H. Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:119–124. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80060-7. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, McNair LD, Seals KL. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. doi:10.1177/088626001016004002. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. Reasons for drinking versus outcome expectancies in the prediction of college student drinking. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:1287–1311. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039379. doi:10.3109/10826089709039379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Ham LS, Feldner MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Sexually Victimized Children. Free Press; New York, NY: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:445–451. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.9.4.445. [Google Scholar]

- Fossos N, Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Lindgren KP, Hove MC. Coping motives as a mediator of the relationship between sexual coercion and problem drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised in undergraduates. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2611–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. doi:10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ. Multiple substance use among adolescent physical and sexual abuse victims. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Krupnick J, Stockton P, Hooper L, Green BL. The psychological impact of types of sexual trauma among college women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:547–555. doi: 10.1002/jts.20063. doi:10.1002/jts.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnick J, Green BL, Stockton P, Goodman L, Corcoran C, Petty R. Mental health effects of adolescent trauma exposure in a female college sample: Exploring differential outcomes based on experiences of unique trauma types and dimensions. Psychiatry. 2004;67:264–279. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.3.264.48986. doi:10.1521/psyc.67.3.264.48986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH. Why my classmates drink: Drinking motives of classroom peers as predictors of individual drinking motives and alcohol use in adolescence – A mediational model. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:536–546. doi: 10.1177/1359105309103573. doi:10.1177/1359105309103573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Patrick ME, Neighbors C. The social norms of alcohol-related negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0018020. doi:10.1037/a0018020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Litt DM, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Granato H, Kilmer JR, Lee CM. They drink how much and where? Normative perceptions by drinking contexts and their association to college student’s alcohol consumption. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:844–853. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rees M, Lee CM. Gender-specific normative perceptions of alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:539–545. doi: 10.1037/a0015176. doi:10.1037/a0015176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Blayney JA, Mullins PM, Kaysen D. Do drinking motives mediate the association between sexual assault and problem drinking? Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell M, Silove D, Creamer M, Horsley K. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;188:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Marx BP, Simpson SM. Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:205–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, Carney MA. Moving beyond the key party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. Prospective effects of sexual victimization on PTSD and problem drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:965–968. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Simpson TL, Moore SA, Varra AA, Kaysen DL. The correspondence of daily and retrospective PTSD reports among female victims of sexual assault. Psychological Assessment. 2012 May 21; doi: 10.1037/a0028518. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0028518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Kaysen D, Dillworth T, Brajcich M, Larimer ME. Incapacitated rape, alcohol use, and consequences in Asian American college students. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(8):919–933. doi: 10.1177/1077801210377470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg MM, Norton AR, Oliver J, Zvolensky MJ. Social anxiety, reasons for drinking, and college students. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA. Coercive sexual experiences, protective behavioral strategies, alcohol expectancies and consumption among male and female college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1563–1578. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354581. doi:10.1177/0886260509354581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Miller BA. Bar victimization of women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21:509–525. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00128.x. [Google Scholar]

- Porche MB, Fortuna LR, Lin J, Alegria M. Childhood trauma and psychiatric disorders as correlates of school dropout in a national sample of young adults. Child Development. 2011;82:982–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01534.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: Two preliminary investigations. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:643–655. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00024-7. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(95)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck AM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and alcohol symptoms in females: Causal inferences and hypothesized mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1069–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00257-5. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Pitts VL. Exploring a feminist routine activities approach to explaining sexual assault. Justice Quarterly. 1995;12:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Quinn PD, Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Perceived norms for drinking in the transition from high school to college and beyond. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:895–903. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Mitchell TL, Wright KD, Loba P. The relations of PTSD symptoms to alcohol use and coping drinking in volunteers who responded to the Swissair Flight 111 airline disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2004;18:51–68. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relation between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–171. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00213-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and problem drinking in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Molnar BE, Davenport AE, Baer JS. College alcohol use: A full or empty glass? Journal of American College Health. 1999;47:247–252. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H, Labouvie E. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]