Abstract

Background

Individuals with alcohol problems frequently report receipt of pressure from a variety of formal and informal sources. While some studies have shown a positive association between receipt of pressure and treatment seeking, other studies have not found a clear association. The mix of findings may be due to several study design factors including sample limitations, lack of contextual alcohol measures as moderators, and failure to include assessment of internal beliefs that relate to help seeking.

Methods

Current drinkers from the National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) from 1984-2005 (N=16,183) were used to describe the association between pressure and help seeking using moderators that included frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related negative consequences, and beliefs about abstention or moderation of alcohol consumption.

Results

The rate of help seeking in the past year was 1.6% across all NAS surveys with Alcoholics Anonymous being the predominant source of help sought followed by physical or mental health services. In 1984 and 1990 approximately 80% of those seeking help also received pressure. The percent declined to 57% in 1995 and leveled off at 64% in 2000 and 61% in 2005. Logistic regression models showed an association between past year receipt of pressure and help seeking. Frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related negative consequences, and strong beliefs about alcohol use were also associated with help seeking, however, they did not moderate the relationship between pressure and help seeking.

Conclusions

Pressure is associated with help seeking as are a variety of other factors, including heavy alcohol consumption, negative consequences, and strong beliefs about moderate alcohol use. However, the effect of these factors appears to be independent of pressure and not interactive. Future research needs to assess the types of pressure and impact on help seeking to inform public policy and treatment providers as to who receives what type of pressure, when it is helpful, and when it is counterproductive.

Keywords: alcohol, pressure, help seeking, alcohol treatment, general population

1. Introduction

Individuals with alcohol problems frequently receive pressure to make changes in their drinking (Room, 1989; Room, Bondy, & Ferris, 1996). Data obtained from national surveys of the U.S. general population over the past 21 years Polcin et al (2012) found that receiving pressure during the past 12 months to decrease drinking or act differently when drinking ranged from about 13% in 1984 to 8% in 2005. Examining the characteristics of who received pressure revealed clear evidence that individuals who were heavy drinkers (5+ drinks per week) and those with greater alcohol related harm received more pressure. However, there were also a variety of demographic predictors of pressure (e.g., male gender, younger and less educated) that suggested that the social context where drinking takes place might also influence who receives pressure.

Separate from the question of who receives pressure is the question of the association between receipt of pressure and help seeking. The vast majority of individuals with alcohol problems do not receive help from treatment or mutual help groups (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration & Office of Applied Studies, 2009) even though those who receive treatment or attend Alcoholics Anonymous fare much better than those who do not (Weisner, Matzger, & Kaskutas, 2003). The present study seeks to examine the association between pressure and help seeking and to expand on prior research by: 1) using representative samples of the US population, thereby avoiding limited geographic location or samples limited to treatment seekers; 2) examine moderating effects of contextual factors. Moderators such as alcohol related harm, alcohol related consequences, and alcohol consumption in relation to receipt of drinking pressures has largely been overlooked; 3) use internal and external factors related to help seeking. While studies have examined associations between pressure and help seeking, they have failed to determine if help seeking was connected with better recognition of drinking problems or simply compliance with external demands; 4) change over time. Studies have not assessed how pressure and its impact might vary at different periods in time.

We hypothesize that individuals receiving pressure will be more likely than those not receiving pressure to seek help for alcohol problems. However, because the majority of individuals with alcohol related problems or alcohol dependence do not seek treatment, we believe that pressure alone cannot entirely explain help seeking for alcohol problems but that heavier drinkers and individuals that report more alcohol related consequences will receive pressure and be more likely to seek out services to aid in abating problematic alcohol use. We also believe that individuals that have stronger beliefs about alcohol use in moderation or abstention from alcohol use and receive pressure will be more likely to seek out help for alcohol related problems. Additionally, strong beliefs about abstention or moderation in drinking is expected to be associated with help seeking which will also be positively linked to pressure received.

2. Methods

2.1 Survey Data

This study draws on five National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) (1984 – 2005) administered approximately every 5 years by the Alcohol Research Group (ARG). The surveys were primarily designed to document trends in alcohol consumption among U.S. residents age 18 and older. However, the NAS surveys have also tracked related variables relevant to this analysis, such as the social context of drinking, pressure to change drinking, ways of seeking help for alcohol problems, and the prevalence of various types of alcohol related harm.

The five administrations of the NAS (1984, 1990, 1995, 2000, and 2005) are highly comparable, particularly in regard to similar item content. Differences in the surveys include over-sampling for Latino/Hispanics and African Americans in four surveys (1984, 1995, 2000, 2005) and use of random digit dial (RDD) telephone survey methods for the last two surveys (2000 and 2005) while the earlier surveys were multi-stage clustered samples using in-person interviews. All surveys are weighted to reflect the general population of the United States so over-sampling of minorities does not bias the results because they are accounted for by the weights in the analysis (Kerr, Greenfield, Bond, Ye, & Rehm, 2004). Response rates were 77% in 1984, 70% in 1990, 77% in 1995, 58% in 2000, and 56% in 2005. Extensive methodological work, comparing the face-to-face and telephone modes of the survey interview found prevalence estimates of drinking behaviors to be substantively comparable, in spite of lower response rates for telephone interviews. For a more detailed discussion of the NAS surveys and comparability across time see Polcin et al (2012).

2.2 Measures

All NAS items are designed to maximize consistency across survey years so that there could be comparisons over time. The measures described below were all administered in all survey years and, with the exception of demographics, refer to the past 12 months. Because our measure of alcohol-related pressure is only asked of persons that consumed alcohol in the past 12 months, analyses exclude non-current drinkers.

2.2.1 Demographics

These items consisted of gender, age, race, marital status, employment status, and years of education to describe the characteristics of who received services and pressure at each NAS survey.

2.2.2 Pressure

Pressure was coded as a dichotomous measure and consisted of 6 items measuring pressure from spouse/intimate partner, family, friends, physicians, work, and police in the past 12 months. Four items asked whether the respondent experienced specific types of interactions that involved pressure to change drinking: 1) My spouse or someone I lived with got angry about my drinking or the way I behaved while drinking; 2) A physician suggested that I cut down on drinking; 3) People at work indicated I should cut down on drinking and; 4) A police officer questioned or warned me about my drinking. Two additional sources asked whether “other people might have liked you to drink less or act differently when you drank” and include: 1) Friends (inclusive of friend or boy/girlfriend); and 2) Family (inclusive of parents or other relatives). The measurement of pressure, and variations of it, have been used at ARG for many years (Hasin, 1994; Polcin et al., in press; Room, 1989; Room et al., 1991).

2.2.3 Help Seeking

Help seeking constitutes the primary dependent variable in our models testing the impact of pressure. Combined analyses will be assessed for dichotomous measure of help seeking through Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), alcohol and drug programs, mental or physical health professionals or programs, and other health services as well as a measure of any help seeking, consisting of any of the four sources. For each, respondents were asked whether they had ever “gone there about a drinking problem.” If they indicated yes, they were asked how long ago. Our primary objective is to assess help seeking over the past 12 months and its association with pressure. Like the measurement of pressure, the NAS help seeking measures have been used effectively in a number of previous studies (Hasin, 1994; Kaskutas, Weisner, & Caetano, 1997; Schmidt, Ye, Greenfield, & Bond, 2007).

2.2.4 Frequent Heavy Drinking

Heavy alcohol consumption was calculated using the “Knupfer Series” (KS) beverage-specific, graduated-frequencies items (Greenfield, 2000; Nyaronga et al., 2009). The KS items ask the frequencies of drinking specific beverages including wine, beer, and distilled spirits using a categorical scale, followed in each case by asking the proportion of time the respondent drinks each beverage in three quantity ranges (one to two, three to four, and five or more drinks). The current drinkers that reported drinking 5 or more drinks in a sitting on at least a weekly basis in the past 12 months were considered to be frequent heavy drinkers.

2.2.5 Alcohol Related Negative Consequences

Consequences of drinking were based on eleven questions about the negative consequences related to drinking and identify 4 important alcohol related problem areas: work problems (2 items), fights/arguments (3 items), legal problems (3 items) and health problems/injury due to alcohol (3 items). Similar consequence measures have been used in the NAS (Greenfield, Nayak, Bond, Ye, & Midanik, 2006; Lown, Nayak, Korcha, & Greenfield, 2011; L. Midanik & Greenfield, 2000). A dichotomous measure indicated having experienced any of these consequences due to drinking in the past 12 months.

Beliefs about drinking in moderation or abstention

This measure consists of 5 items assessing potential reasons for “abstaining from alcohol or being careful about how much you drink”. Items include beliefs that drinking is bad for your health, against your religion, will make you regretful afterward, it will upset family and friends, and drinking will cause a loss of control over your life. Categorical response ranges from 0 to 3 were rated from ‘not at all important’ to ‘very important’. The items were summed for a scale score up to 15 as well as a 3 category measures broken down by tertiles of ‘low’, ‘moderate’, and ‘strong’ belief categories. The scale showed good reliability (0.78) in accordance with recommended guidelines (Cicchetti, 1994). These items were included in all NAS surveys with the exception of 311 cases in 2005 that were balloted and not asked these items.

2.3 Analytic Strategy

Because we were interested in pressure to quit or change drinking behavior and its association with help seeking in the past 12 months, only the respondents who indicated they had consumed at least one alcoholic beverage during the past 12 months were used for the present analysis (N=16,183). The majority of individuals in the NAS surveys were current drinkers, ranging from 61% of the respondents in 2000 to 69% in 1984 with no significant differences across the survey years.

All analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Software v.11 (Stata Corp., 2009). Reported sample sizes are unweighted while percentages and odds ratios are weighted. Chi square comparisons across NAS years were conducted for Figures 1 and 2. Multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model (Table 3) reports the association of pressure, frequent heavy drinking, negative consequences, and beliefs about moderation in drinking to any help seeking in the past 12 months. Additional models were implemented to ascertain the moderating effects of frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related negative consequences, and beliefs about alcohol to understand the association of pressure to help seeking.

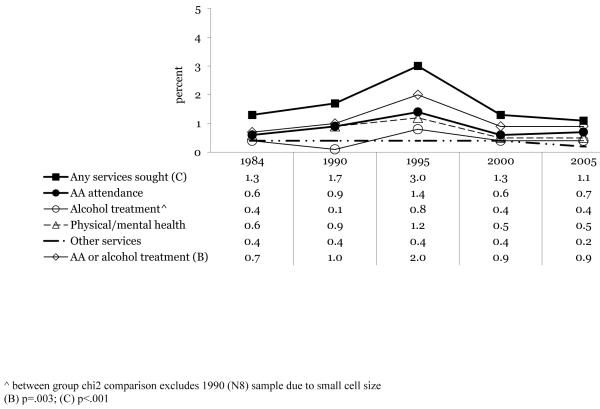

Figure 1.

Percent of current drinkers seeking any alcohol related services in the past 12 months by NAS year (n=291).

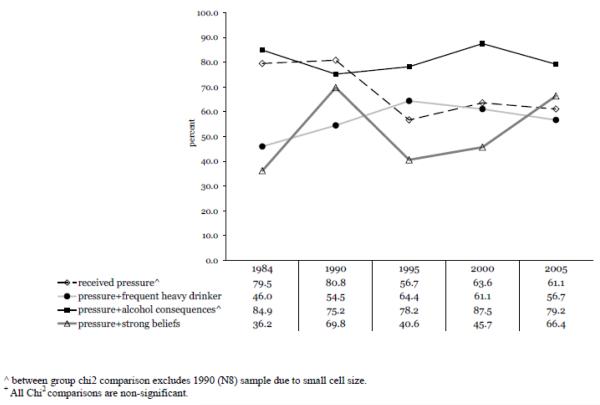

Figure 2.

Percent receiving pressure, drinking behavior, consequences, and beliefs among persons that sought any alcohol related services in the past 12 months by NAS year (current drinkers, weighted; N=291)+.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model predicting any help seeking in the past 12-months among current drinkers (N=15,675)+

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| ORadj | 95% CI | |

|

|

||

| Pressure from any of 6 sources (ref=no pressure) |

5.4 C | 3.2, 9.1 |

| Frequent heavy drinker (ref=not frequent heavy drinker) |

1.9 B | 1.2, 2.9 |

| 1+ consequences (ref=no consequences) |

3.3 C | 2.1, 5.2 |

| Beliefs (ref = low beliefs) moderate beliefs |

2.2 B | 1.2, 4.0 |

| strong beliefs | 4.1 C | 2.4, 7.1 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Model controls for NAS survey year, gender, age, ethnicity, education, employment, and marital status.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Demographically, respondents were predominantly over the age of 29 (74.1%) with a mean age of 42.1 (range 18-104). The gender distribution was nearly equal (51.8% male) and most individuals were either married or in a cohabitating relationship (Table 1). Nearly 80% of the sample was white and the majority had received at least some college education. The percent of past year frequent heavy drinkers, as measured by weekly consumption of five or more drinks in a sitting, was 9.4% with similar rates for those reporting alcohol related consequences (10.4%) and pressure to quit or act differently while drinking (11.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and alcohol treatment service for all NAS surveys (current drinkers, N=16,183).

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

|

|

||

| Demographics | ||

| NAS survey year | ||

| 1984 (N7) | 3182 | 20.7 |

| 1990 (N8) | 1324 | 7.7 |

| 1995 (N9) | 2811 | 18.2 |

| 2000 (N10) | 4617 | 26.6 |

| 2005 (N11) | 4249 | 26.8 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 8145 | 51.8 |

| Age | ||

| 18-29 | 4052 | 25.9 |

| 30-49 | 7203 | 43.4 |

| 50+ | 4790 | 30.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 9342 | 78.4 |

| African-American | 3258 | 9.3 |

| Hispanic | 3098 | 8.5 |

| Other | 485 | 3.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabitating | 9261 | 66.4 |

| sep/wid/div | 3454 | 14.6 |

| never married | 3424 | 19.0 |

| Education | ||

| LT high school | 2744 | 12.2 |

| HS graduate | 4894 | 31.9 |

| some college | 4065 | 26.1 |

| college graduate | 4443 | 29.8 |

| Employment | ||

| full-time (>=35 hours/week) | 9636 | 60.4 |

| part-time (<35 hours/week) | 1686 | 11.2 |

| other | 4845 | 28.4 |

| Alcohol related measures (past 12 mos) | ||

| Pressure to quit or change drinking | 1923 | 11.2 |

| Frequent heavy drinker (5+ weekly drinking) | 1558 | 9.4 |

| 1+ consequences | 1756 | 10.4 |

| Beliefs about abstaining or drinking in moderation& | ||

| low | 4789 | 32.8 |

| moderate | 5499 | 34.6 |

| strong | 5584 | 32.6 |

| Help seeking (past 12 months) | ||

| AA Attendance | 163 | 0.8 |

| Alcohol related treatment | 75 | 0.4 |

| Physical or mental health | 123 | 0.7 |

| Other services (welfare, EAP, other) | 72 | 0.4 |

| Combined measures of help seeking | ||

| AA or alcohol treatment | 201 | 1.1 |

| Any alcohol related services | 291 | 1.6 |

n=311 cases from 2005 (N11) not asked these items.

3.2 Help seeking

Rates of help seeking for all NAS survey years ranged from 0.4% (Alcohol treatment program and other services) to 0.8% (Alcoholics Anonymous, or AA) of the respondents (Table 1). Individuals that sought out any help represented 1.6% of the sample and those seeking out providers of alcohol specific services of AA or alcohol treatment services was 1.1%.

3.3 Help seeking by NAS survey year

Figure 1 displays the percent that sought out alcohol related services by NAS survey year. Help seeking for the specific services of AA, alcohol treatment program, physical or mental health professionals, or other services ranged from 0.1% to 1.4%. The rate of seeking out any help remained relatively steady at each survey year with the exception of NAS survey year 1995, (Figure 1) with three percent of 1995 respondents seeking any help for alcohol problems while the other survey years (1984, 1990, 2000, and 2005) demonstrated lower rates of help seeking ranging from 1.1 to 1.7% . The 1995 respondents reported the highest rates of help seeking for all categories compared to the other NAS survey years however, only physical/mental health (X2=15.4, p<.05), AA or alcohol treatment program attendance (X2=25.6, p<.01), and seeking out any services (X2=47.0, p<.001) significantly differed across groups. AA meeting attendance showed a trend toward significance across NAS survey years with percents ranging from 0.6%-1.4% (X2=15.3, p=.05). A total of six comparisons were conducted for each service category across NAS years and after using a Bonferroni adjustment for the number of comparisons reduced the observed significant test of differences in the rates of AA and Physical/Mental health outcomes to non-significance. However, effects for any services and for AA or alcohol treatment outcomes remained significant after the adjustment.

3.4 Association of pressure and help seeking

The association of pressure and help seeking by each service category is shown in Table 2. Over half of the current drinkers seeking help also reported receiving pressure in the past year with similar rates of pressure and help seeking ranging from 61.9% for other services to 68.9% for attendance to AA. Table 2 also explores whether those receiving pressure were frequent heavy drinkers, reported any alcohol related consequences, or held strong beliefs about moderation or abstention from alcohol use within each of the help seeking categories. The percent of those experiencing pressure and frequent heavy drinking was highest among current drinkers that sought help using physical or mental health services with 55 of the 92 respondents (65.7%, weighted) reporting help seeking and both alcohol related problems. Nearly all of the current drinkers that sought out other services (44 out of 48; 91.9%) reported pressure and had at least one consequence due to alcohol use in the past year while the other service categories of AA attendance, alcohol treatment and physical/mental health services were all above 80%. The association between strong beliefs about drinking and pressure was generally lower across the help seeking categories than for those that had pressure and frequent heavy drinking or pressure and alcohol related consequences.

Table 2.

Receipt of alcohol related services in the past 12 months by pressure, pressure and frequent heavy drinker, pressure and negative conseauences and pressure and strong beliefs about drinking in moderation (in percent).

| AA attendance (n=163) |

Alcohol treatment (n=75) |

Physical or mental health (n=123) |

Other services (n=72) |

AA attendance or Alcohol treatment (n=201) |

Any alcohol related services (n=291) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Received pressure* | 111 | 68.9 | 53 | 67.4 | 92 | 68.8 | 48 | 61.9 | 135 | 67.9 | 191 | 64.9 |

| Received pressure and… Frequent heavy drinking |

65 | 58.0 | 28 | 50.9 | 55 | 65.7 | 27 | 49.3 | 77 | 55.5 | 110 | 57.4 |

| 1+ consequences | 96 | 83.9 | 45 | 80.0 | 79 | 80.6 | 44 | 91.9 | 115 | 84.4 | 161 | 81.5 |

| Strong beliefs+ | 65 | 61.0 | 25 | 37.8 | 48 | 46.8 | 28 | 44.9 | 71 | 53.0 | 97 | 47.8 |

any pressure includes past 12 month pressure from spouse/intimate, family, friends, work, doctor, or police.

strong beliefs are a score in the top 1/3 of the beliefs scale supporting abstention or moderate use of alcohol

A graphic depiction of the association of help seeking to pressure, frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related consequences, and strong beliefs about alcohol use across NAS years is presented in Figure 2. Comparisons across NAS survey years were conducted to assess any changes in the rate of individuals receiving pressure and seeking help for alcohol problems and if these rates changed with the addition of frequent heavy drinking, negative consequences, or strong beliefs about drinking in moderation, resulting in a total of four Chi square comparisons. The percentage of persons seeking help and also receiving pressure declined over the NAS survey years with approximately 80% in 1984 and 1990 and declining to rates of 56.7%, 63.6%, and 61.1% (for 1995, 2000 and 2005 respectively) though this decline was not statistically significant when comparing NAS years 1984, 1995, 2000, and 2005. NAS survey year 1990 was excluded due to a small cell size in 1990 where only 4 respondents seeking help did not receive pressure. Similarly, significance of pressure and alcohol related negative consequences across NAS survey years also excluded 1990. The rates of pressure with frequent heavy drinking and strong beliefs about moderate drinking did not differ across survey years.

3.5 Models predicting any help seeking

Results for the logistic regression model (Table 3), inclusive of all NAS survey years, shows the relative association of pressure, frequent heavy drinking, negative consequences, and beliefs about alcohol to seeking any type of help for alcohol problems, controlling for survey year and demographics. Pressure was most highly associated with help seeking, followed by alcohol related negative consequences, beliefs about drinking in moderation, and frequent heavy drinking. Additionally, models (not shown in table) using drinking pattern, as defined by frequency of any drinking (e.g., lt monthly, monthly, weekly, or daily) and frequency of 5+ drinking (yearly, monthly, weekly or more) were also examined to understand if other styles of drinking were associated with help seeking. Only heavy drinking (i.e., 5 or more drinks) at least one time per week was predictive of help seeking.

3.6 Alcohol and belief measures as moderators of pressure and help seeking

Three additional models (not shown) were conducted to estimate if there were significant interactions between pressure and the other alcohol related measures. Though negative consequences trended toward modifying the relationship between pressure and help seeking (p=.07), none of the interaction models were significant.

4. Discussion

This study supports prior work (Hasin, 1994) showing that pressure to alter one’s drinking or change behavior while drinking is associated with seeking assistance for alcohol related problems. Although we hypothesized that a variety of factors would moderate the relationship between pressure and help seeking (e.g., frequent heavy drinking, alcohol related consequences, and beliefs about drinking), we found independent rather than interactive effects. Thus, individuals were more likely to seek help if they received pressure, were frequent heavy drinkers, experienced alcohol related consequences and had beliefs that drinking was harmful. One implication of this finding is that the association between pressure and help seeking appears to be robust across drinker characteristics. The effect of pressure on help seeking does not appear to be dependent upon or even influenced by these other variables. Rather, there is an additive effect, where the impact of pressure and each of these other variables independently increases the odds of help seeking. However, findings should be taken cautiously as frequent heavy drinking, negative consequences and, to a lesser extent, beliefs about drinking in moderation are also associated with pressure to change drinking behavior among those seeking treatment (Figure 2). Though collinearity is a possibility, we believe these measures to be important in addressing the issues with which we were most concerned, particularly how pressure, drinking behavior, consequences, and beliefs interact to assist individuals to seek out help for alcohol problems.

Additionally, the study illustrates the changes in prevalence of help seeking over a span of 21 years (Figure 1) and assesses the changes in prevalence of pressure and alcohol related problems for persons seeking out help (Figure 2). Though not statistically significant, an observable decline in past year pressure among help seekers occurred after NAS survey year 1990, where rates dropped from approximately 80% to 57% in 1995 and leveling for NAS years 2000 and 2005

We believed that pressure would be associated with help seeking but that a stronger association would emerge when individuals have a frequent heavy drinking pattern or experience negative consequences due to alcohol use. This belief is based, in part, on Willenbring’s (Willenbring, 2007) contention that help seeking appears to be associated with social pressure to seek help together with alcohol related crises. He noted that clinicians have long reported this occurrence as precursors to alcohol treatment entry. Our findings show that pressure, alcohol related negative consequences, frequent heavy drinking, and beliefs about alcohol are predictive in the overall model (Table 3), with pressure and negative consequences showing the strongest association. This intuitively makes sense as negative consequences of drinking are tangible problems that are more likely to become evident to those in the social network, particularly the intimate circle of family and friends where pressure is most likely to be received (Polcin, Korcha, Greenfield, Kerr, & Bond, in press). Frequent heavy drinking, though problematic, shows a lower association with help seeking than negative consequences although we found that pressure and frequent heavy drinking displays the highest incidence of seeking medical or mental health services for alcohol problems (65.7%, Table 2) than other services.

To the best of our knowledge, beliefs about alcohol have not been assessed in terms of the impact on how pressure relates to help seeking but positive beliefs that treatment can alleviate alcohol problems has been shown to be associated with better outcomes (Demmel et al., 2006; Morojele, 1992). We posited that persons with pressure and beliefs that support abstaining from drinking or drinking in moderation would be more likely to seek treatment. A clear association of alcohol beliefs showed that individuals that recognized the potentially destructive consequences associated with drinking were also more likely to seek help in the past year.

4.1 Limitations

While this study shows strength in describing pressure and help seeking using general population data over 21 years, there are limitations. Study findings are based on cross-sectional national surveys and can show changes in prevalence and associations but causal links between pressure, help seeking, and drinking cannot be inferred. To capture the occurrence of pressure and help seeking in the same time frame, we limited our work to the past 12 months and did not consider the respondents who had sought help prior to the past year. And, because our measure of pressure was to quit or change behavior while drinking, we could only use the persons that were currently drinking (i.e, past 12 months), thereby not being able to consider pressure and help seeking among ex-drinkers. It is possible that pressure to remain sober is an important component to seeking help for persons not currently using alcohol but our measures could not capture those individuals. There is also a possibility that this work over-identifies ”unsuccessful’ (i.e., still drinking alcohol) help seekers although treatment attendance and abstinence do not always show a clear pattern (Kaskutas, Bond, & Ammon Avalos, 2009). But, because timing between receipt of pressure, help seeking and drinking cannot be established we can only indicate associations. Lastly, prevalence rates of help seeking in the general population were quite low throughout the survey years (ranging from 1.1% to 3.0% for any services sought) and the clinical revelance of help seeking cannot be implied.

4.2 Conclusions

Heavy drinking, negative consequences, and strong beliefs about moderate drinking showed a strong association with help seeking, but none of these factors moderated the relationship between pressure and help seeking as we had originally hypothesized. Findings suggest that pressure to quit or change drinking behavior and to seek help is not limited to narrow circumstances such as heavy drinking or problems due to alcohol. Future work needs to assess the types of pressure and impact on help seeking to inform public policy and treatment providers as to who receives what type of pressure, when it is helpful, and when it is counterproductive.

Acknowledgements

Funded by NIAAA grant R21AA018174 and P50 AA005595.

Funding was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA grants R21AA018174 and P50 AA005595). NIAAA had no role in the design, implementation, or analysis of the study nor did NIAAA take part in writing the paper or the decision to publish findings. Dr. Polcin was instrumental in developing and implementing the study and wrote the first draft of the introduction. Ms. Korcha conducted analyses and wrote the first draft of the abstract, methods, results and discussion with additional editorial support by Drs. Polcin, Kerr, and Greenfield. Dr. Bond contributed statistical consultation and editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosure

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. Effects of telephone versus face-to-face interview modes on reports of alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2000;95:227–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95227714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Nayak MB, Bond J, Ye Y, Midanik LT. Maximum quantity consumed and alcohol-related problems: assessing the most alcohol drunk with two measures. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1576–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Treatment/self-help for alcohol-related problems: relationship to social pressure and alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:660–666. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Bond J, Ammon Avalos L. 7-year trajectories of Alcoholics Anonymous attendance and associations with treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R. Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984-1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:155–161. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age, period and cohort influences on beer, wine and spirits consumption trends in the US National Surveys. Addiction. 2004;99:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown EA, Nayak MB, Korcha RA, Greenfield TK. Child physical and sexual abuse: a comprehensive look at alcohol consumption patterns, consequences, and dependence from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik L, Greenfield TK. Trends in social consequences and dependence symptoms in the United States: the National Alcohol Surveys, 1984-1995. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:53–56. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. American Public Health Association. Atlanta, GA: Oct 21-25, 2001. Defining “current drinkers” in national surveys: results of the Year 2000-2001 National Alcohol Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Defining “current drinkers” in national surveys: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Addiction. 2003a;98:517–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003b;72:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Reports of alcohol-related harm: telephone versus face-to-face interviews. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:74–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Hines AM, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Face-to-face versus telephone interviews: using cognitive methods to assess alcohol survey questions. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1999;26:673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha RK, Greenfield TK, Kerr WC, Bond JC. Twenty-one year trends and correlates of pressure to change drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01638.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R. The U.S. general population’s experiences of responding to alcohol problems. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:1291–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Bondy SJ, Ferris J. Determinants of suggestions for alcohol treatment. Addiction. 1996;91:643–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9156432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Bond J. Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp . Stata Corporation; College Station, TX: 2009. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.0. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of Applied Studies . The NSDUH Report: Alcohol Treatment: Need, utilization, and barriers. Rockville, MD: [accessed 08/02/2010]. 2009. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/AlcTX/AlcTX.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Matzger H, Kaskutas LA. How important is treatment? One-year outcomes of treated and untreated alcohol-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2003;98:901–911. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenbring ML. A broader view of change in drinking behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:84S–86S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]