Abstract

Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3-K9) mediates heterochromatin formation by forming a binding site for HP1 and also participates in silencing gene expression at euchromatic sites. ESET, G9a, SUV39-h1, SUV39-h2, and Eu-HMTase are histone methyltransferases that catalyze H3-K9 methylation in mammalian cells. Previous studies demonstrate that the SUV39-h proteins are preferentially targeted to the pericentric heterochromatin, and mice lacking both Suv39-h genes show cytogenetic abnormalities and an increased incidence of lymphoma. G9a methylates H3-K9 in euchromatin, and G9a null embryos die at 8.5 days postcoitum (dpc). G9a null embryo stem (ES) cells show altered DNA methylation in the Prader-Willi imprinted region and ectopic expression of the Mage genes. So far, an Eu-HMTase mouse knockout has not been reported. ESET catalyzes methylation of H3-K9 and localizes mainly in euchromatin. To investigate the in vivo function of Eset, we have generated an allele that lacks the entire pre- and post-SET domains and that expresses lacZ under the endogenous regulation of the Eset gene. We found that zygotic Eset expression begins at the blastocyst stage and is ubiquitous during postimplantation mouse development, while the maternal Eset transcripts are present in oocytes and persist throughout preimplantation development. The homozygous mutations of Eset resulted in peri-implantation lethality between 3.5 and 5.5 dpc. Blastocysts null for Eset were recovered but in less than Mendelian ratios. Upon culturing, 18 of 24 Eset−/− blastocysts showed defective growth of the inner cell mass and, in contrast to the ∼65% recovery of wild-type and Eset+/− ES cells, no Eset−/− ES cell lines were obtained. Global H3-K9 trimethylation and DNA methylation at IAP repeats in Eset−/− blastocyst outgrowths were not dramatically altered. Together, these results suggest that Eset is required for peri-implantation development and the survival of ES cells.

Covalent modifications of DNA and the core histones, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, sometimes referred to as “epigenetic” modifications because the DNA protein-coding sequence is unchanged, are involved in both the regulation of gene expression in euchromatin and stabilization of heterochromatin (13). Epigenetic control of gene expression in euchromatin may be achieved by stabilizing chromatin structure, rendering gene expression states mitotically heritable and stable. Epigenetic modifications of heterochromatin appear to play important roles in maintaining chromosomal stability, which if deregulated can result in cancer (5).

DNA methylation of cytosines in CpG dinucleotides is required for mammalian development and has important functions in the regulation of genome stability, X inactivation, and allele-specific expression of imprinted genes (1, 14, 15). Inactivation of Dnmt1 or both Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b by gene targeting or inheritance of oocytes from a Dnmt3L null mother results in lethality at ∼9.5 days postcoitum (dpc) (2, 6, 15, 21). While the exact mechanism underlying the lethality of these embryos remains unknown, the lethality of embryos derived from Dnmt3L−/− mothers suggests that deregulation of gene expression is probably the primary cause. Embryos from Dnmt3L−/− mothers show normal levels of DNA methylation in interspersed repeats and pericentromeric heterochromatin but lack the DNA methylation associated with the maternal imprints that are established during oocyte development and that regulate imprinted gene expression.

The core histones that form the nucleosomes are subject to many covalent modifications, such as phosphorylation, methylation, and acetylation to name a few (32). For instance, histone H3 can be methylated on lysines 4, 9, 27, 36, and 79 (32). Previous work has demonstrated that, similar to DNA methylation, modifications of histones that influence gene expression when inactivated in the mouse result in premature death of the developing embryos. Homozygous mutant embryos have been shown to die at ∼6.0 dpc with mutation of Ezh2, encoding an H3-K27 histone methyltransferase, at ∼8.5 dpc with mutation of G9a, encoding a H3-K9 histone methyltransferase, and at ∼9.5 dpc with mutation of HDAC1, encoding a histone deacetylase (10, 18, 26). In contrast, nearly one-half the mice lacking both Suv39-h genes are viable. These results suggest that, similar to DNA methylation, epigenetic regulation of the expression of euchromatic genes by histone modification is required for embryonic development.

A surprising result from Neurospora crassa demonstrates that H3-K9 methylation catalyzed by dim-5, specifically trimethylation of H3-K9, directs DNA methylation of CpG dinucleotides (27, 28). Further, non-CpG methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana depends on H3-K9 methylation (7). For the mouse, previous studies have shown that Suv39-h1, Suv39-h2, G9a, Eset, and Eu-HMTase all encode enzymes that catalyze H3-K9 methylation (19, 20, 22, 25, 31). Studies of Suv39 double-null cells show that only the pericentromeric heterochromatin exhibits a partial loss of DNA methylation exclusively at MaeII sites in contrast to HpaII sites (12). Further, studies of G9a also demonstrated an additional link between histone methylation and DNA methylation in the mouse; DNA methylation at the Prader-Willi imprinting center is lost in G9a−/− embryo stem (ES) cells (30). Because ESET is capable of catalyzing di- to trimethylation of H3-K9 residues (29), we began this study with the goal of describing the phenotype of mice that lack Eset and also determining whether DNA methylation in part or in whole depends on the H3-K9 trimethylation catalyzed by ESET. We show here that Eset null embryos exhibit peri-implantation lethality. Further, inactivation of Eset does not appear to affect global H3-K9 trimethylation or genome-wide DNA methylation of IAP repeats at the blastocyst stage.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Generation of Eset mutant mice

The mouse Eset cDNA was used to screen a lambda phage library of mouse genomic DNA. The 22 clones obtained were further screened by Southern blotting using the Eset pre- and post-SET domains as a probe. This yielded two clones, which were subcloned into pBluescript, sequenced, and aligned to the Celera mouse genome. With the aim of eliminating all catalytic activity, a construct was made with a short arm of 1.7 kb and long arm of 5.0 kb that replaced exons 15 through 22 (exons 15 to 22 span the entire pre- and post-SET catalytic domains) with an IRES-β-geo cassette (Fig. 1A) (16). The linearized plasmid was electroporated into J1 mouse ES cells, and Eset+/− ES clones were injected into B6 blastocysts to generate chimeras.

FIG. 1.

Generation of a null Eset allele in the mouse. (A) Schematic representation of the genomic structure of Eset (top), followed by the targeting vector and finally the targeted Eset locus. Deletion of exons 15 to 22 removed the entire pre- and post-SET domains, which, based on biochemical studies, eliminates all H3-K9 catalytic activity. MBD, methyl-CpG binding domain. (B) Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA probed with a 500-bp 3′ probe external to the targeting vector confirms, by the appearance of an ∼7-kb band in contrast to the ∼14-kb wild-type (wt) band, correct homologous recombination of one allele. KO, knockout.

Histology, embryo collection, and X-Gal staining

Pregnant mice from Eset+/− intercrosses were scored for fertilization by the appearance of a plug, and decidua were isolated from euthanized females at around noon on the day of dissection. Mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos were obtained from superovulated female mice. Embryos at different cleavage stages were removed by oviduct flushing at an appropriate time post-hCG injection according to standard procedures. Peri-implantation embryos were stained for X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as described previously (9). Standard histological serial sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin staining of 5.5- and 6.5-dpc embryos were performed to identify presumptive Eset−/− embryos. X-Gal staining of postimplantation embryos was performed as previously described (21).

Blastocyst culturing and ES cell derivation

To determine whether Eset−/− blastocysts were viable and if Eset−/− ES cells could be generated, Eset+/− mice were intercrossed by either natural mating or superovulation, and morulae or blastocysts were collected at 2.5 or 3.5 dpc. The morulae and blastocysts were cultured until the late blastocyst stage and then placed in individual wells in ES media for 4 days in the absence of feeder cells. Photographs of the inner cell mass (ICM) and trophoblast cells were taken with a charge-coupled device camera and light microscope. The ICMs were dissociated for derivation of ES cell lines, and the remaining trophoblast cells were used for PCR genotyping with the following primers: Eset-common, 5′-CTCCAGGGGTTAGGCACTCTG-3′, Eset-wild type, 5′-GCGTTTGTTACACTCATAAACC-3′, and Eset-mutant, 5′-CTCCAACCTCCGCAAACTCCTATTT-3′.

Antibody staining and DNA methylation analysis

We analyzed ESET protein and histone di- and trimethylation of H3-K9 in the presumptive Eset−/− blastocysts and blastocyst outgrowths by immunostaining. The specific antibodies against ESET, dimethyl-H3-K9, and trimethyl-H3-K9 were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at 4°C, followed by three 20-min washes in 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS, and permeabilized by 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The embryos were blocked overnight at 4°C in 1% bovine serum albumin-0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. Primary antibody (diluted by 1:50 to 1:100) incubations were carried out in the blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature, followed by several washes for 1 h. Dye (Alexa-488 or -555)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes; 1:300 to 1:500 dilution) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by washes for 30 min. Genomic DNA was stained with 300 nM 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole hydrochloride (DAPI; Molecular Probes) in PBS for 20 min, followed by several washes. Embryos were mounted on slides after drying and observed with a Zeiss fluorescence microscope. Images were captured digitally with different filter sets and merged with Adobe Photoshop software (version 5.5). Using the DNA from three or four pooled ICM outgrowths from Eset+/− or Eset−/− genotyped samples, we performed sodium bisulfite sequencing as previously described (3). The primers to IAP were originally described by Lane et al. (11).

RESULT

Generation of a null mutation at the Eset locus

The Eset gene was mutated by replacement of the pre- and post-SET catalytic region with an IRES-β-geo cassette (an internal ribosomal entry site directed expression of a β-galactosidase-neomycin fusion protein) using standard gene targeting techniques. The deletion of exons 15 to 22, spanning ∼7 kb, removed the entire pre- and post-SET domains and, based on previous biochemical studies of Eset, is predicted to abolish all catalytic activity (Fig. 1A) (23, 31). The correct targeting of the Eset locus was confirmed by Southern blot analysis using an ∼500-bp 3′ probe external to the targeting vector (Fig. 1B). Approximately 13% (11 of the 84) of the ES colonies obtained after G418 selection showed correct targeting of the Eset locus. ES lines 16, 26, and 82 were injected into B6 blastocysts to generated germ line chimeras. Germ line transmission was achieved with line 26, and all experiments presented here were done with line 26.

Eset expression during mouse embryogenesis

We took advantage of the IRES-β-geo cassette, which resulted in expression of lacZ under the regulation of the endogenous Eset promoter, and thus X-Gal staining served as a reporter that mimics Eset expression (16). The immature oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage were positive for X-Gal expression (data not shown). In addition, mature oocytes were positive for X-Gal, suggesting that Eset transcripts (and possibly the maternal ESET protein) are present in mature oocytes (Fig. 2A). Further, when Eset+/− female mice were crossed with Eset+/− male mice, almost all four-cell and eight-cell embryos, morulae, and blastocysts stained positive for X-Gal (Fig. 2A). Because 25% of these embryos would be expected to be Eset+/+ and lack the lacZ transgene, this raised the possibility that a maternal stock of ESET protein persists from the oocyte to the blastocyst stage. To test the possibility that a maternal stock of ESET was the reason all preimplantation embryos were X-Gal positive, we crossed Eset+/− male mice with wild-type females and assayed for X-Gal staining. As suggested by our initial X-Gal staining of preimplantation embryos, a positive X-Gal signal was obtained in none of the two-cell-stage embryos (n = 15) or in four- and eight-cell-stage embryos (n = 28). However, 1 of 27 morulae and 19 of 31 blastocysts scored positive for X-Gal staining (Fig. 2A). Therefore, zygotic transcription of Eset does not begin until the blastocyst stage, and ESET exists as a maternal stock during preimplantation development. We further examined Eset expression in the developing embryo by staining 7.5-, 8.5-, and 9.5-dpc embryos from Eset+/− males crossed to wild-type females. We found ubiquitous staining of the embryo proper in ∼50% of the embryos examined from each litter (Fig. 2B to D). In addition, X-Gal staining was ubiquitous at the 12.5- and 14.5-dpc stages (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Expression of Eset during mouse embryonic development. Eset transcription was analyzed by X-Gal staining, which detects lacZ expression from the targeted Eset allele. (A) Four-cell and eight-cell oocytes, morulae, and blastocysts derived from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice were all positive for X-Gal staining (left). In contrast, embryos derived from crosses between an Eset+/− male and a wild-type female were almost all negative for X-Gal staining from the two-cell stage through the morula stage (right). Only 1 of 27 morulae was X-Gal positive, whereas about one-half (19 of 31) of the blastocysts were X-Gal positive. (B to D) X-Gal staining of Eset+/− embryos at 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 dpc showed ubiquitous expression of Eset throughout the entire embryo proper. In panels C and D the yolk sac is still attached to the embryo and also stained positive for X-Gal.

Lack of Eset results in peri-implantation lethality

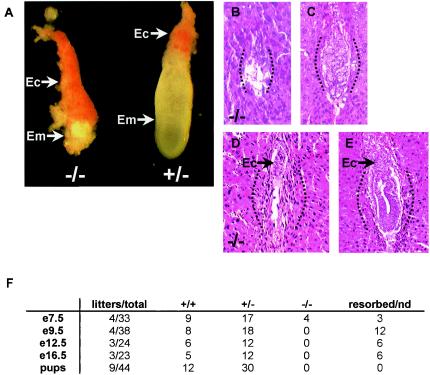

Embryos from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice were isolated and analyzed at 9.5 to 16.5 dpc, and no Eset−/− embryos were recovered (Fig. 3F). However, of 33 embryos isolated at 7.5 dpc, 4 were Eset−/− as determined by PCR genotyping, and three other deciduae were resorbed such that no genotype could be obtained. All four Eset−/− embryos were severely malformed, with the embryonic tissues almost completely resorbed, whereas the trophectoderm-derived ectoplacental cone was relatively normal in size (Fig. 3A and F). To determine when Eset homozygous mutant embryos died, we performed serial sectioning and staining with hematoxylin and eosin of two litters each at 5.5 and 6.5 dpc. The majority of embryos showed normal morphology at 5.5 or 6.5 dpc, but some lacked any discernible embryonic tissue within the deciduae and were considered presumptive Eset null embryos. These presumptive Eset null embryos showed a complete lack of the development of the embryo proper, and at 6.5 dpc only the ectoplacental cone was discernible, similar to the embryos recovered at 7.5 dpc (Fig. 3B to E). These results suggest that the longest-surviving Eset−/− embryos die shortly after implantation due to failure of the primitive ectoderm to develop properly.

FIG. 3.

Fate of Eset−/− embryos. (A) An Eset−/− embryo (left) and an Eset+/− littermate at 7.5 dpc. All Eset−/− embryos (Em) at 7.5 dpc were severely malformed, with only the ectoplacental cone discernible (Ec). (B to E) Approximately sagittal sections from presumptive Eset−/− embryos (B and D) show extensive resorption and the absence of any detectable structure of the embryo proper at 5.5 and 6.5 dpc (arrows [D and E], ectoplacental cones; dotted lines, general outline of each decidua); the majority of embryos showing normal morphology at 5.5 and 6.5 dpc (C and E) were presumptive Eset+/− or wild-type embryos (2 litters each; 2 of 14 at 5.5 dpc appeared to be resorbing, and 2 of 17 at 6.5 dpc appeared to be resorbing). (F) Results of Eset+/− intercrosses. After 7.5 dpc no Eset−/− embryos were recovered at 9.5, 12.5, or 16.5 dpc, and no viable pups were recovered at weaning. nd, not determined.

Eset null mutation prevents proper development of the ICM and establishment of ES cells

To determine the cellular defect in the Eset−/− blastocysts, we cultured blastocysts in vitro and analyzed their morphology. A total of 136 blastocysts were isolated and genotyped from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice (Table 1). We recovered only 24 Eset−/− blastocysts (a reduction of ∼33% compared to the expected number of 36). To test whether Eset−/− ES cells were viable, we isolated blastocysts derived from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice by natural breeding and superovulation. Blastocysts were then hatched from the zona pellucida and grown for 4 days. The ICMs from the resulting colonies were picked and dissociated to allow the derivation of ES cell lines (Fig. 4A). The genotype of each blastocyst outgrowth was determined by PCR of the remaining trophoblast cells. Of 24 Eset−/− blastocysts only 6 had normal ICM morphology and none gave rise to ES cell lines, while ∼65% of the wild-type and Eset+/− blastocysts yielded ES cell lines (Fig. 4B, Table 1, and data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Establishment of mouse ES cell lines from wild-type and Eset−/− blastocystsa

| Expt | No. collected | No. that were:

|

No. of Eset−/− blastocystsb with ICM:

|

No. of Eset−/− ES cell lines recovered/no. of blastocysts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eset+/+ | Eset+/− | Eset−/− | Bad morphology | Normal morphology | |||

| 1 | 23 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0/8 |

| 2 | 33 | 7 | 21 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0/5 |

| 3 | 16 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0/2 |

| 4 | 29 | 10 | 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0/2 |

| 5 | 32 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0/7 |

| Total | 136 | 37 | 72 | 24 | 18/24 | 6/24 | 0/24 |

Of 136 morulae and blastocysts isolated from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice, 24 Eset−/− embryos were recovered, 18 of which showed defective ICM growth. While ES cell lines were established from ∼65% of Eset+/− and wild-type blastocysts (data not shown), none of the 24 Eset−/− blastocysts yielded ES cell lines.

Out of a total of 24.

FIG. 4.

Defective ICM outgrowth of Eset−/− blastocysts. (A) After 3 to 4 days of culture many wild-type and Eset+/− blastocyst outgrowths show normal ICM morphology above the trophectodermal cell layer. Here, an Eset+/− culture is shown (see Table 1). (B) Of the 24 Eset−/− blastocysts obtained, 18 showed defective ICM morphology after 3 to 4 days in culture; the example shown here is a particularly severe one. (C) PCR genotyping of the remaining trophectodermal cells after picking up the ICM outgrowth for the derivation of ES cells allowed the determination of the genotype by size separation on a 3% agarose gel. wt, wild type; KO, knockout. (D) Schematic of the PCR genotyping protocol. The same forward primer anneals to both the targeted (KO) and wild-type Eset alleles, but the reverse primers are specific to either the wild-type Eset locus or the IRES-β-geo inserted cassette and are distinguished by their different sizes.

In parallel to using ICM outgrowths as a means to derive ES cells, we also tried to induce gene conversion by selection of Eset+/− ES cells for loss of the other Eset allele with high concentrations of G418 as previously described (21). Although ∼60 colonies were recovered after selection in 5- to 7-mg/ml G418, no Eset−/− ES cell lines were obtained by this technique. These experiments strongly suggest that Eset is required for the survival of the mouse ICM and ES cells.

Eset−/− blastocyst outgrowths do not show global alterations in H3-K9 trimethylation or DNA methylation

Due to the limited number of Ese−/− cells available for study, we were unable to assay gene-specific changes in H3-K9 methylation by chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. We thus tried to determine the effects of Eset mutation on global levels of histone trimethylation and also global levels of DNA methylation. We collected 33 intact blastocysts from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice and stained them using antibodies specific for di- and trimethylation of H3-K9. The di- and trimethylation of H3-K9 did not show any difference in antibody staining among the 33 blastocysts analyzed (Fig. 5). These results suggested no global defect in di- or trimethylation of H3-K9 in Eset−/− blastocysts; however, it was possible that a maternal stock of Eset “rescues” global H3-K9 methylation in Eset−/− blastocysts. If true, only after zygotic expression begins and the maternal stock is exhausted would we be able to assay for the effects of loss of ESET on global histone methylation or global DNA methylation levels.

FIG. 5.

Di- and trimethylation of H3-K9 in the Eset−/− blastocyst. Thirty-three blastocysts from Eset+/− intercrosses were used. (A) Bright-field microscopy showed normal morphology of all blastocysts. (B) Immunostaining of blastocysts with an anti-dimethyl-H3-K9 antibody. No differences in staining among the 33 blastocysts were detected. (C) Immunostaining of blastocysts with an anti-trimethyl-H3-K9 antibody. No differences among the 33 blastocysts were detected. (D) Merge of images in panels B and C. The anti-di- and anti-trimethyl-H3-K9 signals show colocalization, as judged by the appearance of orange in the merged images. (E) DAPI staining of DNA (blue).

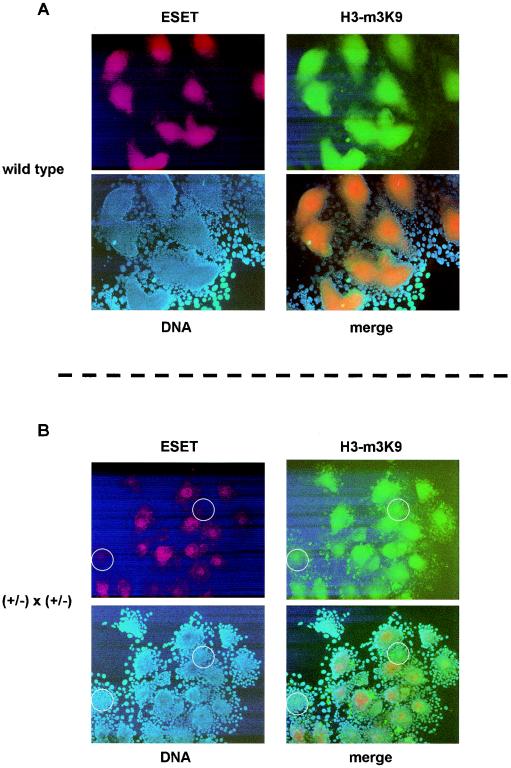

To test whether Eset−/− cells that show reduced staining for the ESET protein also show reduced staining for H3-K9 trimethylation, we first analyzed blastocyst outgrowths from wild-type crosses that were allowed to hatch and grow for 3 days (the same procedure used to derive ES cells; Fig. 4 and Table 1). In these experiments, all colonies showed robust ESET and global H3-K9 trimethylation staining (Fig. 6A). Next, in the hope that blastocyst outgrowths would exhaust the maternal stock of ESET, we examined 21 blastocyst outgrowths from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice. These results showed a wide variation in ESET signal; however, the H3-K9 trimethylation signal appears to be independent of ESET levels (Fig. 6B). Thus, while it is conceivable that the maternal stock of ESET present during preimplantation development persists during blastocyst outgrowth and prevents true loss-of-function analysis, our results suggest that ESET, at this stage of development, does not control global H3-K9 trimethylation.

FIG. 6.

ESET protein expression and H3-K9 trimethylation (H3-m3K9) in blastocyst outgrowths. (A) Wild-type mice were intercrossed to ensure that ESET was detectable by immunostaining. All 10 blastocyst outgrowths derived from wild-type intercrosses showed similar levels of staining with an ESET antibody (red) and an H3-K9 trimethylation antibody (green). The DNA is detected by DAPI staining (blue), and the merged image shows colocalization of ESET and H3-K9 trimethylation. (B) Experiments similar to those shown in panel A were performed using blastocyst outgrowths from intercrosses of Eset+/− mice. A variation in the ESET signal (red) among the 21 blastocyst outgrowths was readily observed; however, the loss of ESET signal (red) did not correlate with the loss of the H3-K9 trimethylation signal (green). The DNA was detected by DAPI staining (blue), and the merged image shows colocalization of ESET and H3-K9 trimethylation. Two blastocyst outgrowths that show low ESET signal are highlighted with white circles for comparison with the still-detectable H3-K9 trimethylation signal.

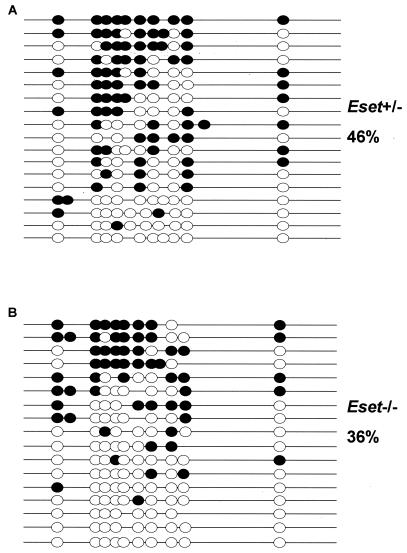

In addition, using DNA from the ICMs of three or four pooled Eset+/− or Eset−/− blastocysts picked after 3 days of culture, we performed DNA methylation analysis by sodium bisulfite sequencing of the repetitive sequence IAP. Previous studies on blastocysts found an ∼60% methylation of IAP without a reduction in methylation levels from the fertilized egg to the blastocyst stage, making this sequence an ideal candidate to study whether Eset mutation alters global DNA methylation levels (11). We found that 36% of CpG sites were methylated in the Eset−/− DNA compared to 46% in the Eset+/− DNA (Fig. 7). However, we cannot conclude that this small difference was caused by the loss of ESET and a possible subsequent defect in H3-K9 trimethylation. In conclusion, these results suggest that DNA methylation at this developmental stage is not regulated by ESET, but the persistence of a maternal stock prevents us from drawing a definite conclusion.

FIG. 7.

DNA methylation analysis of IAP repeats isolated after 3 days of ICM growth in culture. (A) A total of 46% of all CpG sites were methylated in the DNA recovered from the three or four pooled ICM samples obtained from Eset+/− blastocyst outgrowths. As described previously the remaining trophectodermal cells were used for PCR genotyping. (B) A total of 36% of all CpG sites were methylated in the DNA recovered from three or four pooled ICMs obtained from Eset−/− blastocyst outgrowths.

DISCUSSION

Eset deletion results in peri-implantation lethality

The requirement of the de novo and maintenance DNA methyltransferase genes and several histone methyltransferase genes, including Ezh2, G9a, and Eset, during mouse embryonic development indicates that epigenetic silencing of specific genes or the genome as a whole is an essential process during mouse development. Dynamic changes in DNA methylation patterns and histone modification are known to occur during preimplantation and early postimplantation mouse development (8, 13, 24). Eset mutation results in peri-implantation lethality from 3.5 to 5.5 dpc, which precedes that of all mouse embryos with other epigenetic mutations thus far described. Thus it is possible that Eset participates in the earliest stages of epigenetic reprogramming. In addition, the loss of Eset prevented the derivation of mouse ES cells. Consistent with the notion that Eset is required for cell viability, the study of Wang et al. showed that the human ortholog SETDB1, when inactivated by RNA interference (RNAi) from human cancer cell lines, also resulted in cell lethality (29). From these results, in combination with the study presented here, it appears that Eset function is required for cell viability.

Maternal ESET during preimplantation development

Using the lacZ reporter, we show that Eset is expressed in the oocytes and that zygotic Eset is not turned on until the blastocyst stage. The fact that the majority of Eset null embryos die before implantation or shortly after implantation is consistent with the notion that the maternal ESET functions in preimplantation embryos and that the zygotic ESET starts to function at the time of implantation when maternal ESET becomes exhausted. These results suggest that if it were possible to eliminate the maternal stock of ESET (for instance, by targeting Eset transcripts for degradation by RNAi), it might result in an earlier preimplantation lethality corresponding to the timing of the depletion of the Eset maternal stock. Future studies that employ RNAi epialleles against Eset could help resolve the in vivo role of Eset during mouse preimplantation development.

Possible roles for Eset in mouse development

Eset encodes a SET domain-containing protein that in synergy with the transcriptional repressor mAM catalyzes the methylation of histone H3-K9, including the conversion of di- to trimethyl-H3-K9 (29). Since trimethylation of H3-K9 has been frequently associated with silent genes and heterochromatin, it is possible that, in Eset mutant embryos, normally silent genes become ectopically activated, resulting in abnormal development of the embryo. There are two possible ways by which ESET might be essential to mouse development: (i) Eset might regulate genome-wide H3-K9 methylation and perhaps thereby also direct global DNA methylation to ensure proper regulation of heterochromatin and parasitic transposons or (ii) Eset might regulate H3-K9 trimethylation in specific euchromatic regions, thereby regulating gene expression and perhaps also directing DNA methylation to specific genes in euchromatin, where regulated gene expression is essential to mouse development.

We did not observe a significant decrease in H3-K9 trimethylation, suggesting that Eset may not have a role in directing global H3-K9 trimethylation. However, the possibility that the maternal stock of ESET rescues true loss of function cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, our results are more consistent with ESET carrying out trimethylation of H3-K9 at specific genes in the euchromatin. This would be consistent with the extant literature, where genes such as Ezh2, Oct4, and YY1 are all associated with similar levels of peri-implanation lethality (4, 17, 18). In all these cases, the genes mutated have roles in regulating gene expression. However, the specific targets in the euchromatin subject to regulation are not well elucidated. Given that Eset was cloned in a yeast two-hybrid screen using the transcription factor ERG as the bait, it is possible that ESET methylates H3-K9 in genes that are regulated by ERG (31). Due to the limited number of Eset−/− cells available for study, we were not able to empirically test ESET's role in regulating H3-K9 methylation in euchromatin.

In conclusion, we report here that Eset is required for peri-implantation development and exists as a maternal stock during preimplantation development prior to the onset of zygotic transcription at the blastocyst stage. To determine whether ESET trimethylation of H3-K9 controls DNA methylation, we analyzed DNA methylation of the endogenous retrotransposon IAP. Our results favor a model in which ESET functions to regulate gene expression at specific euchromatic sites and does not have a role in regulating global H3-K9 trimethylation or global DNA methylation. Further studies with conditional or hypomorphic Eset alleles are needed to define whether or not Eset has a role in regulating DNA methylation in the mouse.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants (CA82389 and GM52106) to E.L. and an institutional NRSA postdoctoral fellowship award to the Cardiovascular Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital supported J.E.D. Y.-K.K. was supported in part by the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of Korea Science and Engineering Foundation.

We thank Myrtha Constant of the CBRC for histological analysis of early mouse embryos.

REFERENCE

- 1.Beard, C., E. Li, and R. Jaenisch. 1995. Loss of methylation activates Xist in somatic but not in embryonic cells. Genes Dev. 9:2325-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourc'his, D., G. L. Xu, C. S. Lin, B. Bollman, and T. H. Bestor. 2001. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science 294:2536-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodge, J. E., A. F. List, and B. W. Futscher. 1998. Selective variegated methylation of the p15 CpG island in acute myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 78:561-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohoe, M. E., X. Zhang, L. McGinnis, J. Biggers, E. Li, and Y. Shi. 1999. Targeted disruption of mouse Yin Yang 1 transcription factor results in peri-implantation lethality. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7237-7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudet, F., J. G. Hodgson, A. Eden, L. Jackson-Grusby, J. Dausman, J. W. Gray, H. Leonhardt, and R. Jaenisch. 2003. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science 300:489-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hata, K., M. Okano, H. Lei, and E. Li. 2002. Dnmt3L cooperates with the Dnmt3 family of de novo DNA methyltransferases to establish maternal imprints in mice. Development 129:1983-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson, J. P., A. M. Lindroth, X. Cao, and S. E. Jacobsen. 2002. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416:556-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaenisch, R., and A. Bird. 2003. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 33(Suppl.):245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang, Y. K., J. S. Park, C. S. Lee, Y. I. Yeom, A. S. Chung, and K. K. Lee. 1999. Efficient integration of short interspersed element-flanked foreign DNA via homologous recombination. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36585-36591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagger, G., D. O'Carroll, M. Rembold, H. Khier, J. Tischler, G. Weitzer, B. Schuettengruber, C. Hauser, R. Brunmeir, T. Jenuwein, and C. Seiser. 2002. Essential function of histone deacetylase 1 in proliferation control and CDK inhibitor repression. EMBO J. 21:2672-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane, N., W. Dean, S. Erhardt, P. Hajkova, A. Surani, J. Walter, and W. Reik. 2003. Resistance of IAPs to methylation reprogramming may provide a mechanism for epigenetic inheritance in the mouse. Genesis 35:88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehnertz, B., Y. Ueda, A. A. Derijck, U. Braunschweig, L. Perez-Burgos, S. Kubicek, T. Chen, E. Li, T. Jenuwein, and A. H. Peters. 2003. Suv39h-mediated histone h3 lysine 9 methylation directs DNA methylation to major satellite repeats at pericentric heterochromatin. Curr. Biol. 13:1192-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, E. 2002. Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:662-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, E., C. Beard, and R. Jaenisch. 1993. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature 366:362-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, E., T. H. Bestor, and R. Jaenisch. 1992. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69:915-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mountford, P., B. Zevnik, A. Duwel, J. Nichols, M. Li, C. Dani, M. Robertson, I. Chambers, and A. Smith. 1994. Dicistronic targeting constructs: reporters and modifiers of mammalian gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:4303-4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols, J., B. Zevnik, K. Anastassiadis, H. Niwa, D. Klewe-Nebenius, I. Chambers, H. Scholer, and A. Smith. 1998. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 95:379-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Carroll, D., S. Erhardt, M. Pagani, S. C. Barton, M. A. Surani, and T. Jenuwein. 2001. The Polycomb-group gene Ezh2 is required for early mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4330-4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Carroll, D., H. Scherthan, A. H. Peters, S. Opravil, A. R. Haynes, G. Laible, S. Rea, M. Schmid, A. Lebersorger, M. Jerratsch, L. Sattler, M. G. Mattei, P. Denny, S. D. Brown, D. Schweizer, and T. Jenuwein. 2000. Isolation and characterization of Suv39h2, a second histone H3 methyltransferase gene that displays testis-specific expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:9423-9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogawa, H., K. Ishiguro, S. Gaubatz, D. M. Livingston, and Y. Nakatani. 2002. A complex with chromatin modifiers that occupies E2F- and Myc-responsive genes in G0 cells. Science 296:1132-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okano, M., D. W. Bell, D. A. Haber, and E. Li. 1999. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell 99:247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rea, S., F. Eisenhaber, D. O'Carroll, B. D. Strahl, Z. W. Sun, M. Schmid, S. Opravil, K. Mechtler, C. P. Ponting, C. D. Allis, and T. Jenuwein. 2000. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406:593-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz, D. C., K. Ayyanathan, D. Negorev, G. G. Maul, and F. J. Rauscher. 2002. SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 16:919-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surani, A., and A. Smith. 2003. Differentiation and gene regulation. Programming, reprogramming and regeneration. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13:445-447. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tachibana, M., K. Sugimoto, T. Fukushima, and Y. Shinkai. 2001. Set domain-containing protein, G9a, is a novel lysine-preferring mammalian histone methyltransferase with hyperactivity and specific selectivity to lysines 9 and 27 of histone H3. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25309-25317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachibana, M., K. Sugimoto, M. Nozaki, J. Ueda, T. Ohta, M. Ohki, M. Fukuda, N. Takeda, H. Niida, H. Kato, and Y. Shinkai. 2002. G9a histone methyltransferase plays a dominant role in euchromatic histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and is essential for early embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 16:1779-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamaru, H., and E. U. Selker. 2001. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nature 414:277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamaru, H., X. Zhang, D. McMillen, P. B. Singh, J. Nakayama, S. I. Grewal, C. D. Allis, X. Cheng, and E. U. Selker. 2003. Trimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 is a mark for DNA methylation in Neurospora crassa. Nat. Genet. 34:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, H., W. An, R. Cao, L. Xia, H. Erdjument-Bromage, B. Chatton, P. Tempst, R. G. Roeder, and Y. Zhang. 2003. mAM facilitates conversion by ESET of dimethyl to trimethyl lysine 9 of histone H3 to cause transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell 12:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xin, Z., M. Tachibana, M. Guggiari, E. Heard, Y. Shinkai, and J. Wagstaff. 2003. Role of histone methyltransferase G9a in CpG methylation of the Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14996-15000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, L., L. Xia, D. Y. Wu, H. Wang, H. A. Chansky, W. H. Schubach, D. D. Hickstein, and Y. Zhang. 2002. Molecular cloning of ESET, a novel histone H3-specific methyltransferase that interacts with ERG transcription factor. Oncogene 21:148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Y., and D. Reinberg. 2001. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 15:2343-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]