Abstract

Background: Scarce data are available on hemoglobin and platelet in relation to coronary artery spasm (CAS) development. We sought to determine the roles that high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), hemoglobin and platelet play in CAS patients.

Methods: Patients (337 women and 532 men) undergoing coronary angiography with or without CAS but without obstructive coronary artery disease were evaluated during a 12-year period.

Results: Among women with high hemoglobin levels, the odds ratios (OR) from the lowest (<1 mg/l) to the highest tertiles (>3 mg/l) of hs-CRP were 1.21, 2.15, and 5.93 (p=0.009). In women with low hemoglobin levels, an elevated risk was found from the middle to the highest tertiles of hs-CRP (OR 0.59 to 3.85) (p=0.004). This relationship was not observed in men. In men, platelet count was the most significant risk factor for CAS (p=0.004). The highest likelihood of developing CAS was found among women with the highest hs-CRP tertile and low platelet counts (OR 8.77; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.20-35.01) and among men with the highest hs-CRP tertile and high platelet counts (OR 4.58; 95% CI 0.48-43.97). Neither hemoglobin level nor platelet count was associated with frequent recurrent angina in both genders with CAS whereas death and myocardial infarction were rare.

Conclusions: There are positive interactions among hs-CRP, hemoglobin and platelet in women with this disease, but not in men. While hemoglobin is a modifier in CAS development in women, platelet count is an independent risk factor for men. Both women and men have good prognosis of CAS.

Keywords: gender, hemoglobin, platelets, C-reactive protein, coronary spasm

Introduction

Coronary artery spasm (CAS), of which the mechanism is not fully understood, is an important cause of variant angina and ischemic heart disease 1-2. While smoking and inflammation, characterized by elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels 2, 3, may predispose to CAS, they are unlikely to constitute major direct causes of CAS in the whole population of patients with this disease 2. CAS has been even purportedly associated with bitter orange (Citrus aurantium)-containing products 4. Thus, elucidating other potential triggers could represent elusive therapeutic targets. It has long been recognized that red blood cells are vasoactive 5-7. While the benefit of modest anemia to reduce blood viscosity is well established in cerebral spasm 7, 8, it is unclear in CAS. A J-shaped relationship has been observed between hemoglobin (Hb) levels and prognosis, indicating that low and high Hb levels are associated with poor prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) 9. Such an association, however, has never been investigated in patients with CAS.

A dynamic interaction has been demonstrated between platelet aggregates and CAS in myocardial infarction 1. Transient increases in platelet counts are observed in many inflammatory diseases 10. Although there is evidence that women have higher platelet counts and reactivity than men with CAD 11, it is unclear whether there is a similar gender disparity in CAS. We previously demonstrated that the relationship between hs-CRP and CAS in patients without obstructive CAD differed between women and men and that age contributed to CAS development in men 4. Little is known, however, about the effect of the relationship among hs-CRP, Hb and platelet on risk and prognosis for CAS. Therefore, we enrolled more patients with and without CAS to determine whether there are interactions among gender, hs-CRP, Hb and platelet that influence CAS development in patients without obstructive CAD. Furthermore, we determined the long-term prognosis of CAS in these patients.

Methods

Study population

From January 1999 to December 2010, 869 patients with suspected ischemic heart disease and no angiographic evidence of obstructive CAD were subjected to intracoronary methylergonovine testing. Inclusion criteria for patients with CAS included spontaneous chest pain at rest associated with electrocardiographic evidence of ST-segment elevation or depression, subsequently relieved by sublingual administration of nitroglycerin, no angiographic evidence of obstructive CAD after intracoronary nitroglycerin administration, and/or a positive result on intracoronary methylergonovine provocation tests. The control group consisted of patients who presented with atypical chest pain, no angiographic evidence of obstructive CAD, and negative results on intracoronary methylergonovine provocation tests (no CAS). Exclusion criteria included evidence of obstructive CAD, inflammatory manifestations probably associated with noncardiac diseases (e.g., infections and autoimmune disorders), liver disease/renal failure (serum creatinine level >2.5 mg/dl), collagen disease, or malignancy, and loss of blood samples. This study was approved by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board (96-1069B) and the Taipei Medical University-Joint Institutional Review Board (201011004). All patients gave written informed consent.

Definition of terms

Current smoking was defined as having smoked a cigarette within 3 weeks of the cardiac catheterization. Diabetes mellitus was defined from dietary treatment and/or medical therapy. Baseline seated blood pressure is the mean of 6 readings obtained during the first 2 office visits performed 2 weeks apart. Hypertension is defined as blood pressure of >140/90 mmHg or receiving antihypertensive treatment. Hypercholesterolemia was defined where serum total cholesterol was >200 mg/dl.

Laboratory analysis

Blood specimens were collected after an overnight fast immediately before coronary angiography. Serum hs-CRP was measured in duplicate by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (IMMULITE hs-CRP, Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, California). The lower limit of this assay was 0.10 mg/l and coefficients of variation were ≤5% at 0.20 mg/l of C-reactive protein.

Provocative protocol

Coronary angiography was performed using the standard Judkins technique. Nitrates and calcium antagonists were withdrawn for ≥24 hours before the procedure. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using Simpson's method. Obstructive coronary stenosis was defined as a ≥50% reduction in luminal diameter after administration of intracoronary nitroglycerin 12. If no obstructive coronary stenosis was found, intracoronary methylergonovine (Methergin®; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) was administered stepwise (1, 5, 10, 30 μg) first into the right coronary artery and subsequently into the left coronary artery. CAS was defined as a >70% reduction in luminal diameter compared with postintracoronary nitroglycerin, with associated angina and ⁄ or ST depression or elevation 13. Provocation testing was stopped with an intracoronary injection of 50-200 μg of nitroglycerin (Millisrol®; G. Pohl-Boskamp, Hohenlockstedt, Germany). Reversal in coronary artery diameter confirmed the diagnosis of CAS. Spontaneous CAS was defined as the relief of >70% diameter stenosis after intracoronary nitroglycerin 50-200 μg administration.

Follow-up

Patient follow-up data were obtained from medical records of outpatient visits and hospital readmissions or telephone interviews. All patients with the exception of those who died were followed up for at least 12 months. The study end point was the occurrence of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), which is a composite of death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and recurrent angina pectoris requiring repeat coronary angiography. All deaths were considered cardiac-related deaths unless an unequivocal noncardiac cause could be identified. Coronary events were defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction and recurrent angina pectoris requiring repeat coronary angiography.

Of the 869 patients in the initial study, follow-up data were available for 783 patients (90.1%), of whom 293 were women (86.9% follow-up) and 490 were men (92.1% follow-up).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD or as median (interquartile range), and log transformation was performed for variables with positive skewness for the subsequent Student's t tests between 2 groups. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percent) and were analyzed using the chi-square test. Tertiles of hs-CRP were categorized as lowest (<1 mg/l), middle (1-3 mg/l), or highest (>3 mg/l) 14. Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated with multiple logistic regression were used to identify risk factors for CAS in patients without obstructive CAD. Variables were selected based on a priori knowledge and significance of univariate tests while constructing multivariable models. Stratified analyses were performed on a subset of 526 patients whose hs-CRP measurements were available to examine the interaction of hs-CRP tertiles, Hb level (high/low determined by the mean concentration of 13.6 g/dl), and platelet count (high/low determined by the mean count of 205×109/l) on CAS. Differences in incidence of MACE and coronary event-free survival between groups during the follow-up period were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Differences in Hb levels and platelet counts across age groups were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and the post hoc Scheffe's procedure. The level of significance was set at p<0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the 869 patients who underwent diagnostic coronary angiography was 57±12 years, and 39% were women. A total of 495 patients had CAS (spasm group) (Figure 1) and 374 did not have CAS (control group). Advanced age, male gender, and current smoking status were associated with a greater likelihood of developing spasm. Moreover, Hb level, hematocrit, platelet count, and hs-CRP were significantly higher in the spasm group than in the control group (Table 1). Single-vessel spasm was the most common finding in patients with spasm, and spasm was provoked mostly in the right coronary artery. The number of patients who used β-blockers and calcium-channel blockers before coronary angiography was significantly greater in the control group than in the spasm group. However, after coronary angiography, the number of patients who used calcium-channel blockers and nitrates was significantly greater in the spasm group than in the control group.

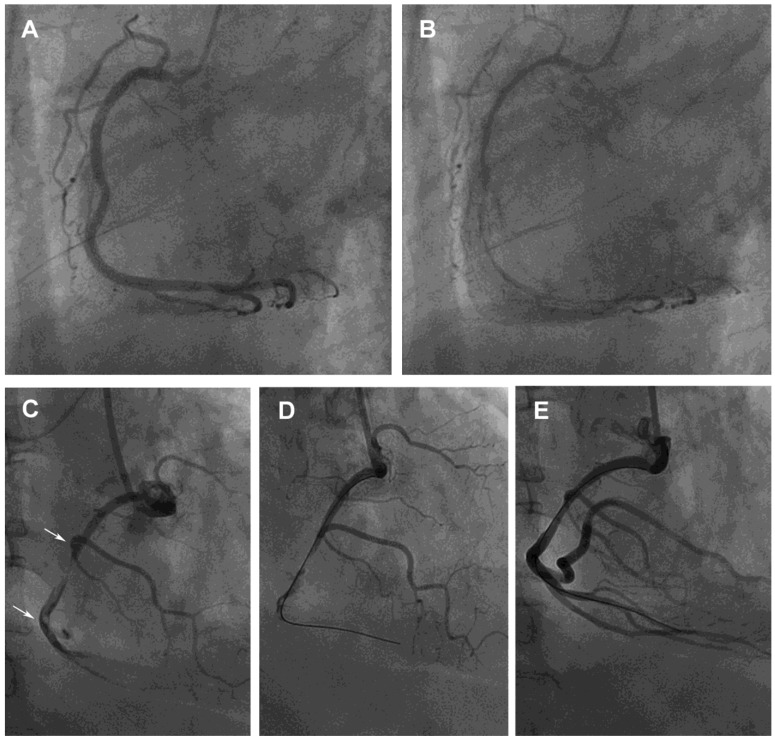

Figure 1.

Provoked coronary spasm and a dynamic interaction between platelet aggregates and spontaneous spasm related to angina and myocardial infarction, respectively. (A) A 62-year-old man had an unstable angina, presenting after wakening with resting chest tightness at night. Baseline angiography showed normal right coronary artery (RCA) with minimal plaquing. (B) Nearly 100% spasm appeared at middle and distal sites after intracoronary administration of 46 μg methylergonovine, which responded to intracoronary nitroglycerin 200 μg. (C) A 59-year-old man, a 15-cigarettes-per-day smoker, with a platelet count of 317×109/l had an acute inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. His platelet count was 264×109/l 1 year before this event. A subtotal occlusion without response to intracoronary nitroglycerin 400 μg with a large intramural thrombus in the mid-RCA (arrows) lead to poor distal runoff flow. (D and E) Manual thrombectomy using a Thrombuster catheter aspirated a large red thrombus clot about 1.5×20 mm. He then developed further chest pain and ST-segment elevation inferiorly. The mid RCA segment showed severe spasm with disappearance of mid and distal flow which responded to intracoronary nitroglycerin 200 μg. ST-segment elevation returned to baseline. He was then started on verapamil and aspirin and was asymptomatic at a 6 month follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | Controls (n=374) |

CAS (n=495) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56±12 | 59±12 | 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 185 (50) | 347 (70) | <0.001 | ||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.0±4.1 | 25.8±3.8 | 0.62 | ||||

| Current smoker | 84 (23) | 223 (45) | <0.001 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 68 (18) | 95 (19) | 0.70 | ||||

| Hypertension | 172 (46) | 217 (44) | 0.51 | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 67±12 | 66±9 | 0.06 | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 204±41 | 199±41 | 0.05 | ||||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 141±37 | 134±45 | 0.10 | ||||

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 37±14 | 37±14 | 0.89 | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.2±1.9 | 13.8±1.6 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hematocrit, % | 39.2±5.4 | 40.7±4.2 | <0.001 | ||||

| Platelet, ×109/l | 197±84 | 211±78 | 0.019 | ||||

| hs-CRP, *† mg/l | 1.24 (0.62-3.08) | 2.28 (0.78-6.68) | <0.001 | ||||

|

Provoked coronary artery Left main artery Left anterior descending artery Left circumflex artery Right coronary artery |

|||||||

| 4 (0.8) 145 (29) |

|||||||

| 109 (22) | |||||||

| 328 (66) | |||||||

|

Number of provoked spastic artery 1-vessel spasm 2-vessel spasm 3-vessel spasm |

|||||||

| 409 (83) | |||||||

| 30 (6) | |||||||

| 56 (11) | |||||||

| Medications | A | D | A | D | A | D | |

| β -blockers | 67 (18) | 30 (8) | 45 (9) | 25 (5) | <0.001 | 0.075 | |

| Calcium-channel blockers | 168 (45) | 150 (40) | 139 (28) | 470 (95) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ACE inhibitors | 34 (9) | 64 (17) | 46 (9) | 92 (19) | 0.919 | 0.575 | |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 56 (15) | 135 (36) | 69 (14) | 198 (40) | 0.667 | 0.241 | |

| Nitrates | 142 (38) | 108 (29) | 198 (40) | 257 (52) | 0.543 | <0.001 | |

| Statins | 37 (10) | 71 (19) | 59 (12) | 114 (23) | 0.345 | 0.149 | |

| Aspirin | 262 (70) | 123 (33) | 332 (67) | 134 (27) | 0.349 | 0.063 | |

| Diuretics | 82 (22) | 41 (11) | 89 (18) | 69 (14) | 0.147 | 0.191 | |

A: before angiography; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; CAS: coronary artery spasm; D: at discharge; hs-CRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Values are given as n (%), mean±SD or median (interquartile range).

* hs-CRP samples were collected in a subset of 526 patients, with 210 and 316 in the control and spasm groups, respectively; †Log-transformed values were used in analyses

Among women, Hb level, hematocrit, and hs-CRP level were positively associated with CAS. Among men, however, age, current smoking status, platelet count and hs-CRP level were positively associated with CAS (Table 2). Among spasm patients, women tended to have a higher LVEF than men. In addition, the prevalence rates of current smokers, high Hb level, and high hematocrit level were higher among men than women.

Table 2.

Gender-specific baseline characteristics between study groups.

| Characteristics | Women (n=337) | Men (n=532) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=189) | CAS (n=148) | p value | Controls (n=185) | CAS (n=347) | p value | p value* | ||

| Age, years | 58±10 | 59±11 | 0.45 | 54±13 | 59±13 | <0.001 | 0.99 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.7±4.3 | 26.1±3.7 | 0.36 | 26.2±3.8 | 25.7±3.8 | 0.14 | 0.27 | |

| Current smoker | 11 (6) | 15 (10) | 0.14 | 73 (40) | 208 (60) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40 (21) | 28 (19) | 0.61 | 28 (15) | 67 (19) | 0.23 | 0.90 | |

| Hypertension | 87 (46) | 71 (48) | 0.72 | 85 (46) | 146 (42) | 0.36 | 0.23 | |

| LVEF, % | 69±12 | 68±9 | 0.59 | 66±12 | 65±9 | 0.32 | 0.003 | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 207±40 | 203±42 | 0.33 | 201±41 | 197±41 | 0.28 | 0.15 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.2±1.6 | 12.7±1.2 | 0.002 | 14.2±1.6 | 14.3±1.5 | 0.69 | <0.001 | |

| Hematocrit, % | 36.6±5.0 | 37.9±3.5 | 0.014 | 41.7±4.6 | 41.9±3.9 | 0.71 | <0.001 | |

| Platelet, ×109/l | 206±89 | 214±84 | 0.45 | 188±78 | 210±76 | 0.005 | 0.66 | |

| hs-CRP,†‡ mg/l | 1.49 (0.72-3.11) | 1.98 (0.90-6.94) | 0.003 | 1.07 (0.50-2.96) | 2.42 (0.71-6.34) | <0.001 | 0.55 | |

CAS: coronary artery spasm; hs-CRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. Values are given as n (%), mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). * Comparison between women and men among patients with CAS; †hs-CRP samples were collected in a subset of 526 patients, with 99 and 93 in the control and spasm groups in women, and 111 and 223 in the control and spasm groups in men, respectively; ‡Log-transformed values were used in analyses.

Gender-specific factors and CAS in the hs-CRP subset

Multivariable stratified analyses demonstrated that the levels of Hb and hs-CRP were associated with CAS among women, with hs-CRP as an independent risk factor. However, age, current smoking status, and platelet count were independently associated with CAS among men (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gender-specific univariate and multivariable analysis of variables associated with CAS.

| Variable | Units of increase | Women(n=337) | Men (n=532) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariable* | Univariate | Multivariable* | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |||

| Age | 1 year | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | 0.45 | 1.00 (0.97-1.04) | 0.79 | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02-1.07) | 0.001 | |

| Body mass index | 1 kg/m2 | 1.03 (0.97-1.08) | 0.36 | 1.02 (0.94-1.12) | 0.62 | 0.97 (0.92-1.01) | 0.14 | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) | 0.30 | |

| Current smoker | 0=no; 1=yes | 1.83 (0.81-4.10) | 0.15 | 2.17 (0.70-6.77) | 0.18 | 2.26 (1.56-3.25) | <0.001 | 1.81 (1.06-3.07) | 0.029 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0=no; 1=yes | 0.87 (0.51-1.49) | 0.61 | 0.42 (0.17-1.06) | 0.07 | 1.34 (0.83-2.18) | 0.23 | 1.24 (0.62-2.48) | 0.54 | |

| Hypertension | 0=no; 1=yes | 1.08 (0.70-1.66) | 0.72 | 0.56 (0.28-1.11) | 0.10 | 0.85 (0.59-1.21) | 0.36 | 0.92 (0.54-1.56) | 0.74 | |

| LVEF | 1 % | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.59 | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.78 | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 0.32 | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | 0.74 | |

| Total cholesterol | 1 mg/dl | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.33 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.15 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.28 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.40 | |

| Hemoglobin | 1 g/dl | 1.31 (1.09-1.56) | 0.003 | 1.48 (0.97-2.26) | 0.07 | 1.03 (0.90-1.17) | 0.69 | 1.24 (0.70-2.21) | 0.46 | |

| Hematocrit | 1 % | 1.08 (1.01-1.14) | 0.016 | 0.92 (0.80-1.06) | 0.26 | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) | 0.71 | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) | 0.52 | |

| Platelet | 1×109/l | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.44 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.97 | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.005 | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 0.004 | |

| hs-CRP* | 1 mg/l | 1.09 (1.02-1.17) | 0.008 | 1.15 (1.06-1.25) | 0.001 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 0.04 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.15 | |

CAS: coronary artery spasm; CI: confidence interval; hs-CRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; OR: odds ratio.

* Multivariable analysis was performed in a subset of 526 patients with hs-CRP measurements, with 192 in women, and 334 in men, respectively

Stratified analyses on hs-CRP tertiles, Hb and platelet

Significant interactions were demonstrated between hs-CRP tertiles and Hb (model 1) and platelet (model 2) on the risk of CAS among women but not in men (Table 4).

Model 1 analysis. In women, high Hb level was a significant modifier for CAS. Women with high and low Hb levels in the highest tertile of hs-CRP had a 5.9-fold (95% CI 1.57-22.37) and a 3.9-fold (95% CI 1.52-9.74) higher risk for CAS, respectively, than those with low Hb levels in the lowest hs-CRP tertile. This relationship was not observed in men.

Model 2 analysis. In men, platelet count was the most significant risk factor for CAS. The highest likelihood of developing CAS was found among women with the highest hs-CRP tertile and low platelet counts (OR 8.77, 95% CI 2.20-35.01) and among men with the highest hs-CRP tertile and high platelet counts (OR 4.58, 95% CI 0.48-43.97, p=0.19).

Table 4.

Stratified analyses of multivariate-adjusted odds ratios for CAS with hs-CRP tertiles, hemoglobin and platelet.

| Model | Women (n=192) | Men (n=334) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile of hs-CRP | Tertile of hs-CRP | |||||||

| <1 mg/l | 1-3 mg/l | >3 mg/l | <1 mg/l | 1-3 mg/l | >3 mg/l | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | <13.6 | 1.0 (reference) | 0.59 (0.22-1.58) | 3.85 (1.52-9.74) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.81 (0.21-3.09) | 1.50 (0.42-5.32) | |

| ≥13.6 | 1.21 (0.29-4.95) | 2.15 (0.52-8.96) | 5.93 (1.57-22.37) | 0.43 (0.13-1.42) | 0.47 (0.14-1.59) | 1.19 (0.36-3.94) | ||

| Platelet (×109/l) | <205 | 1.0 (reference) | 1.07 (0.27-4.32) | 8.77 (2.20-35.01) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.09 (0.54-2.23) | 2.63 (1.35-5.13) | |

| ≥205 | 2.06 (0.62-6.88) | 1.23 (0.35-4.25) | 5.69 (1.65-19.59) | 1.55 (0.63-3.84) | 1.55 (0.42-5.73) | 4.58 (0.48-43.97) | ||

CAS: coronary artery spasm; hs-CRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein. Values are given as odds ratio (95% confidence interval), with adjusted variables including age, body mass index, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, left ventricular ejection fraction, cholesterol and hematocrit other than the stratified variable per se.

Hb, platelet and age

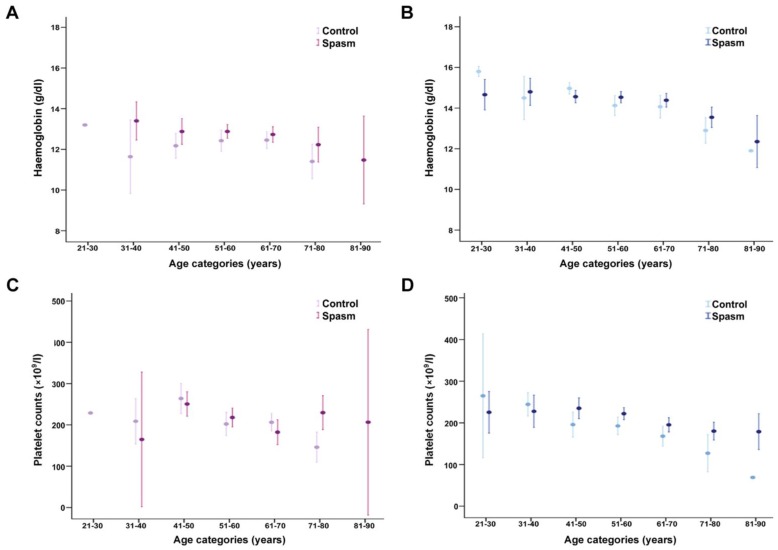

Hb level tended to decrease with advancing age in men, while a moderate decline was observed in women after the age of 50 years (p<0.001 and p=0.018, respectively). In women, patients with spasm had higher Hb levels in every age category than patients without spasm (Figure 2A). However, this pattern was less clear in men (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Geometric mean hemoglobin concentration and platelet count by gender and age. (A and B) Hemoglobin level tended to decrease with advancing age in men, while a moderate decline was observed in women after the age of 50 years (p<0.001 and p=0.018, respectively). In women, patients with spasm had higher hemoglobin levels in every age category than patients without spasm. However, this pattern was less clear in men. (C and D) Women were found to have higher platelet counts than men after 40 years of age. Platelet counts decreased with advancing age in men, while a moderate decline was observed in women after the age of 40 years (p<0.001 for both genders). In men, patients with spasm appeared to have higher platelet counts in most age strata than patients without spasm. Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Men with current smoking status had higher platelet counts than men who did not smoke (p=0.002). Women were found to have higher platelet counts than men after 40 years of age (Figure 2C). Platelet counts decreased with advancing age in men (Figure 2D), while a moderate decline was observed in women after the age of 40 years (p<0.001 for both genders). In men, patients with spasm appeared to have higher platelet counts in most age strata than patients without spasm.

Follow-up data

All patients with the exception of those who died were followed up for at least 12 months (follow-up period: 1 to 144 months; mean 87.9±40.7 months; median 96 months). Five patients in the control group died during the follow-up period (1%), and deaths in all 5 patients were due to a noncardiac cause (septic shock [n=4] or cancer [n=1]). Three deaths occurred in the spasm group (0.6%), and the deaths were due to sudden cardiac death (n=2) or cancer (n=1). Coronary events occurred in 7 (2%) patients in the control group and in 40 (8%) patients in the spasm group. Three nonfatal myocardial infarction events were identified in the spasm group (0.6%).

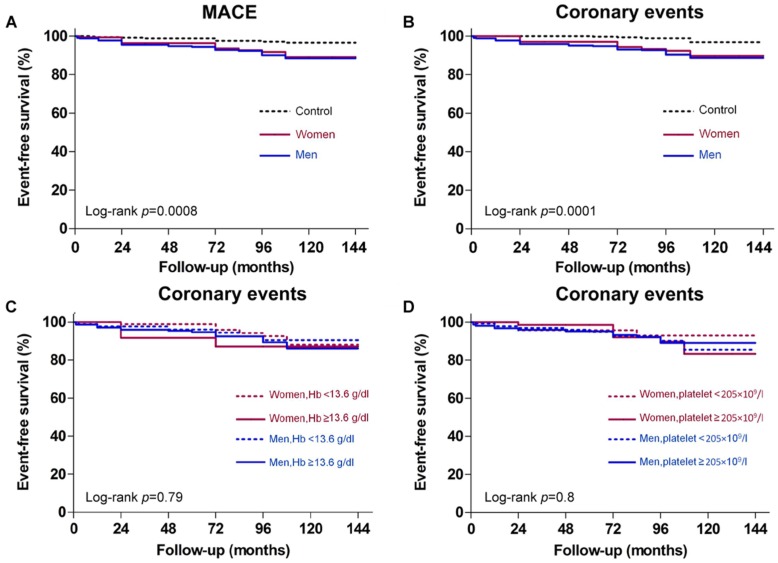

The frequency of MACE-free survival was significantly lower among both genders in the spasm group than in the control group (p=0.0045 for women and p=0.0002 for men) (Figure 3A). Comparison of coronary events between the spasm and control groups equally disclosed a significant difference for both genders (Figure 3B). However, neither Hb level nor platelet count was associated with risk for coronary events (Figure 3C, 3D).

Figure 3.

Gender-specific outcomes according to presence or absence of coronary artery spasm (CAS), higher or lower than mean hemoglobin (Hb) Levels, and higher or lower than mean platelet counts. Kaplan-Meier survival curves of: (A) major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE)-free survival showing the frequency was significantly lower in the CAS group than in the control group; (B) coronary events showing significantly more events in patients with CAS than in controls; (C) coronary events shown for women and men with high or low Hb levels; and (D) coronary events shown for women and men with high or low platelet counts.

Discussion

We found that hs-CRP was an independent risk factor for CAS among women and that age, current smoking status, and platelet count were independently associated with CAS in men. Hb is a potential modifier of the occurrence of CAS in women while platelet count is the most significant risk factor for CAS in men. There are interactions among hs-CRP, Hb and platelet in CAS development in women, but not in men. Prognosis of CAS is similarly good in both women and men, as recurrent angina was frequently observed whereas death and myocardial infarction were rare. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to describe that there are gender differences in the effects of Hb levels and platelet counts on the development of CAS in individuals without obstructive CAD.

Our finding that Hb had a dose dependent effect on CAS development among women has not been previously demonstrated. However, the disparity between genders on the association of Hb with CAS is not fully understood. It has been suggested that women have greater vasodilatory responses and are more resistant to the effects of vasoconstricting signals than men, indicating that overall vascular reactivity is lower in women than in men 15, contributing to the fact that women tolerate a low Hb better than men 16. In this study we did not detect an association between hs-CRP and Hb levels in both genders, eliminating the role of hs-CRP involving in the relationship between Hb levels and CAS development. Among women in model 1 analysis, more patients with low Hb levels had lowest hs-CRP tertile than those with high Hb levels (36% and 27%, respectively), while more patients with high Hb levels had highest hs-CRP tertile than those with low Hb levels (44% and 35%, respectively), suggesting Hb may increase the role of high hs-CRP levels in the development of CAS in women, contributing to the threshold effect of hs-CRP in women with low Hb levels. However, this interaction was not observed in men. Longitudinal studies are needed to investigate whether the different roles of Hb in women and men in CAS development are secondary to hormonal effects.

A previous study has reported a dynamic interaction between platelet aggregates and CAS, in which platelet aggregation may lead to CAS and the constriction may promote further platelet aggragation 1. Enhanced platelet reactivity has been demonstrated in patients with vasospastic angina 17. While a study has proposed that platelets are less thrombotic in women than in men 15, our finding that women with CAS had higher platelet counts than men with CAS suggests that platelet reactivity is dependent on aggregate size of platelets, which represents the activated state of platelet function rather than platelet count per se. It has been shown that testosterone deteriorated only small aggregates while estradiol deteriorated all sizes of aggregates 18. Therefore, it is possible that greater baseline reactivity in women allows for a more prominent reduction in platelet function when exposed to estradiol, contributing to the insignificant role of platelets in CAS development in women. Furthermore, that there was no correlation between hs-CRP level and platelet count in our patients eliminates the role of hs-CRP involvement in determination of platelet count on CAS development. Men with high hs-CRP levels and platelet counts can easily be identified during routine examination and could possibly benefit from early intervention, suggesting that platelet count can serve as a simple and cost-effective biomarker of CAS.

Consistent with a previous report 19, we found that platelet counts were significantly higher among men who smoke than among men that do not smoke. Our observations that men had higher Hb concentrations than women and that older adults had lower Hb levels and platelet counts than younger patients were in line with other studies 20, 21. Furthermore, Hb levels and platelet counts have been found to vary substantially according to age, gender, and race/ethnicity 20, 21. Population-based studies are needed for Hb and platelet to differentiate the causality from predisposing factors through biomarkers to the occurrence of CAS.

There are limitations to this study that should be taken into context when evaluating our results. First, this study is a clinical observational study based on a hospital patient cohort, and not a population-based causality analysis. The observational study design, even with extensive multivariable analysis, cannot prove causal relationships. Accordingly, this observed relationship among Hb, platelet and hs-CRP in CAS development provides valuable information on both mechanistic conjecture and clinical practice. Second, the causes of low or high Hb levels in patients were not examined. Complicated pathways may exist, but they were not explicitly demonstrated in this study. Third, the sample size of women who were current smokers was small, which might have resulted in an underestimation of the effect of smoking on risk for CAS in women. Fourth, the data were collected from a community based teaching hospital. One of the major limitations might be placed as the Berkson's bias under a referral delivery system. In addition, the patients' behavior may be different as opposed to those in the primary care settings.

Conclusions

Among women, hs-CRP is an independent risk factor for CAS development. Age, current smoking status and platelet count are independently associated with CAS among men. There are interactions among hs-CRP, Hb and platelet in women with CAS, but not in men. Hb is a potential modifier of the occurrence of CAS in women while platelet count is the most significant risk factor for CAS in men. These potential triggers of CAS may act in the same patient to cause angina attacks in different conditions. Recurrent episodes of angina are frequently observed in women and men with CAS whereas death and myocardial infarction are rare. Neither Hb level nor platelet count is associated with risk for coronary events. These results may contribute to a basis for the gender differences in CAS development and treatment strategies in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant CMRPG23011 and CMRPG 250131 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Keelung and by Grant NSC 95-2314-B-182A-058 from the National Science Council, Taiwan. We gratefully acknowledge the support we received from the Healthy Aging Research Center (HARC) of the Chang Gung University. We also thank Dr. Ning-I Yang, Li-Tang Kuo, and Chao-Hung Wang for their invaluable support and access to their patient databases.

Abbreviations

- A

before angiography

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CAS

coronary artery spasm

- CI

confidence interval

- D

at discharge

- Hb

hemoglobin

- hs-CRP

high sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular event

- OR

odds ratio.

References

- 1.Oliva PB, Breckinridge JC. Arteriographic evidence of coronary arterial spasm in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1977;56:366–374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanza GA, Careri G, Crea F. Mechanisms of coronary artery spasm. Circulation. 2011;124:1774–1782. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.037283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung MY, Hsu KH, Hung MJ. et al. Interactions among gender, age, hypertension and C-reactive protein in coronary vasospasm. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:1094–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stohs SJ, Preuss HG, Shara M. A Review of the Human Clinical Studies Involving Citrus aurantium (Bitter Orange) Extract and its Primary Protoalkaloid p-Synephrine. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:527–38. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Goldman D. et al. Erythrocytes: oxygen sensors and modulators of vascular tone. Physiology. 2009;24:107–116. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00038.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancaster JR Jr. Simulation of the diffusion and reaction of endogenously produced nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8137–8141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schechter AN, Gladwin MT. Hemoglobin and the paracrine and endocrine functions of nitric oxide. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1483–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr023045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tummala RP, Sheth RN, Heros RC. Hemodilution and fluid management in neurosurgery. Clin Neurosurg. 2006;53:238–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah AD, Nicholas O, Timmis AD. et al. Threshold haemoglobin levels and the prognosis of stable coronary disease: two new cohorts and a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrakis MG, Passam FH, Moschandrea IA. et al. Levels of serum cytokines and acute phase proteins in patients with essential and cancer-related thrombocytosis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:135–140. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breet NJ, Sluman MA, van Berkel MA. et al. Effect of gender difference on platelet reactivity. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:451–457. doi: 10.1007/s12471-011-0189-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharaf BL, Williams DO, Miele NJ. et al. A detailed angiographic analysis of patients with ambulatory electrocardiographic ischemia: results from the Asymptomatic Cardiac Ischemia Pilot (ACIP) study angiographic core laboratory. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyao Y, Kugiyama K, Kawano H. et al. Diffuse intimal thickening of coronary arteries in patients with coronary spastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:432–437. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00729-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al; Centers for Disease Control, Prevention; American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwertz DW, Penckofer S. Sex differences and the effects of sex hormones on hemostasis and vascular reactivity. Heart Lung. 2001;30:401–426. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.118764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arant CB, Wessel TR, Olson MB. et al. Hemoglobin level is an independent predictor for adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women undergoing evaluation for chest pain: results from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2009–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakata K, Hoshino T, Yoshida H. et al. Characteristics of vasospastic angina with exercised-induced ischemia--analysis of parameters of hemostasis and fibrinolysis. Jpn Circ J. 1996;60:277–284. doi: 10.1253/jcj.60.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haque SF, Matsubayashi H, Izumi S. et al. Sex difference in platelet aggregation detected by new aggregometry using light scattering. Endocr J. 2001;48:33–41. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.48.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erikssen J, Hellem A, Stormorken H. Chronic effect of smoking on platelet count and "platelet adhesiveness" in presumably healthy middle-aged men. Thromb Haemost. 1977;38:606–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel KV. Variability and heritability of hemoglobin concentration: an opportunity to improve understanding of anemia in older adults. Haematologica. 2008;93:1281–1283. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal JB, Moliterno AR. Platelet counts differ by sex, ethnicity, and age in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]