Abstract

Objectives. I incorporated qualitative methods to explore how HIV-related stigma functions in New York City’s House and Ball Community (HBC).

Methods. From January through March 2009, I conducted 20 in-depth 1-on-1 interviews with a diverse sample of New York City HBC members. Interviews addressed perceptions of HIV-related stigma, the treatment of HIV-positive members in the community, and the potential impact of HIV-related stigma on risk behaviors.

Results. HIV-related stigma contributes to a loss of moral experience for HBC members. Moral experience (i.e., threats to what really matters in a community) disrupts established social connections and hinders the attainment of “ball status” (i.e., amassing social recognition) in the local world of these individuals.

Conclusions. My recommendations address HIV-related stigma in the New York City HBC from the vantage of moral experience and highlight the need for longitudinal studies of individual house members and for the implementation of stigma-focused interventions in the community that utilize the unique ball status hierarchy and HBC network to influence social norms surrounding the treatment of HIV-positive community members.

The New York City (NYC) House and Ball Community (HBC) is a hard-to-reach population of ethnoracial and sexual minorities that is filled with pride, support, contradictions, gender and sexuality constructs, socioeconomic symbolism, blurring of ethnoracial paradigms, music, dance, and competition.1,2 One study that examined HIV prevalence in the NYC HBC found that of 504 participants, 20% were HIV positive (HIV+), with 74% of those unaware of their HIV+ status.3 NYC remains the most HIV-impacted city in the United States, with ethnoracial and sexual minority health disparities existing among those who are HIV+.4–9 Overall, 82% of HIV+ NYC residents are Black (52%) or Latino (30%). The rate of HIV infections among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) is twice that of their White counterparts, and that of Latino MSM is 55% higher than that of White MSM.10 Clearly, the HIV epidemic in NYC is adversely affecting Black and Latino MSM populations, who make up a large portion of the HBC; however, little research has qualitatively assessed the sociocultural influences of HIV among these individuals.

The NYC HBC has its roots in the Harlem Renaissance and is a vibrant underground community that has evolved into a network of support systems for displaced and marginalized ethnoracial and sexual minorities that helps them find figurative, and sometimes literal, second homes.1,2 The core unit of the HBC is the house, which is governed by non–gender-specific mother and father figures. The general members of a house are known as the children or house kids. Houses come together to compete at events known as balls, which are illustrious fashion and dance sports-like events. Individual house members “walk” (i.e., compete) in various categories in an effort to gain recognition for themselves and for the houses they represent. Gender categories are unique in the HBC, with the 2 dominant genders being “butch queen” (gay and bisexual men) and “femme queen” (transgender women).

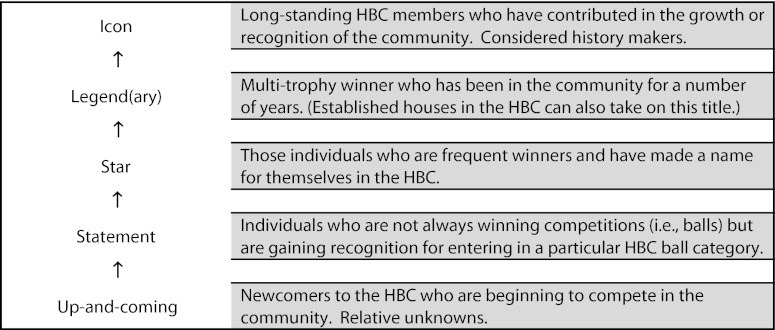

In addition to winning trophies and prizes, the main goal in participating in ball competitions is to amass social recognition, known as “ball status,” which is the factor that creates lines of respect in the HBC. Individual, self-fulfilling titles constitute a ball status hierarchy in the HBC (Figure 1). Members acquire status and move up in this hierarchy on the basis of the number of years they have been involved with the community, number of awards they have won, and number of balls they have participated in through the years.

FIGURE 1—

Ball status hierarchy in the New York City HBC.

Note. HBC = House and Ball Community.

A key term in the community is “shade.” In its most simplistic definition, shade refers to the notion of keeping others down, usually by means of backhanded remarks. In a more complex definition, it denotes the deliberate oppression of other individuals to maintain power relations among those with status. This occurs as higher ranking HBC members influence the beliefs of those of lower standings (e.g., Figure 1 shows how the opinions of individuals with legendary status regarding members with up-and-coming status have more credibility than do lower ranking members’ opinions regarding those with higher status). This process is similar to the influence that popular opinion leaders have in other populations.11–13

In 2004, the House and Ball Survey recruited Black and Latino MSM and transgender individuals in the HBC to complete a questionnaire and take an HIV antibody test.3 That study was the first of its kind to assess infection rates and risk behaviors of HBC members, and it showed that in the prior year, risk behaviors of the participants included having more than 5 sexual partners (26%), unprotected anal intercourse (30%), and sex in exchange for drugs or money (5%). The study also demonstrated that stressors were common among all participants; however, transgender women (i.e., femme queens) were more likely to report experiences of sex work, stigmatization, and stressful life events.14 Stressors identified in that study included depression, perceived stigma, experiences of discrimination, and number of prejudice-related life events. This information is consistent with the minority stress model, which posits that those with multiple minority identities (i.e., ethnoracial and sexual or gender) are exposed to greater proximal (i.e., personal) and distal (i.e., social) stressors.15 This is a particularly important point, as HBC members constitute individuals from multiple stigmatizing populations (e.g., Black and gay) and may experience discrimination from various sources (e.g., home, ball house, employer).

Stigma has long been understood as an attribute that links a person to an undesirable stereotype, leading other people to reduce the individual from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted person.16 In recent years, this notion of stigma has been reconceptualized as “status loss and discrimination,” acknowledging that stigmatization functions at the intersection of culture, power, and difference.17–19 In this respect stigma, prejudice, and discrimination exist as social interactions that enable power dynamics in societies to maintain oppressive mechanisms between the stigmatized and the stigmatizers. In this framework, stigma is viewed as an undesired characteristic, prejudice is the process of holding negative attitudes or beliefs about those who are stigmatized, and discrimination occurs when someone acts on these stigmatized beliefs.20–22 As such, stigma models tend to be concerned with individual-level characteristics, such as HIV-related stigma; and prejudice models usually emphasize social-level characteristics, such as sexual prejudice.23–25

Yang et al.26 describe stigma in terms of “moral experience,” which notes that stigma goes beyond the individual, as family members become stigmatized and vital connections that link the person to a social network of support, resources, and life chances become threatened. The loss of these social links represents the concept of moral experience and connotes the relevance of local worlds. The authors underscore that what defines a local world is the fact that something is at stake. This point is particularly relevant for the HBC, as ball status is the factor that defines their local world. Framing moral experience as a loss of these connections can assist in answering questions regarding HIV-related stigma among HBC members, as the attainment of ball status (i.e., what really matters in their local world) can become threatened. For example, if HIV status is disclosed in a local world that functions as a second home and family to its membership, how does the community respond to that person? Will concealment of HIV status protect one’s ball status? Do houses of known HIV+ persons become discredited and lose popularity in the HBC? Or does drive to achieve ball status influence HIV risk factors?

Recognizing that the NYC HBC is mainly composed of Black and Latino MSM, that there are increases in HIV among urban MSM in NYC, and that risk behaviors and stressors are common among the HBC, I sought to investigate how HIV-related stigma affects the lives of HBC members.

METHODS

I conducted interviews between January and March 2009 in NYC. Inclusion criteria for the study were being aged 18 years or older and being a self-identified member of the HBC. Community descriptors of butch queen and femme queen are the reported gender categories. Given that prior research suggests associations of HIV serostatus, gender and ethnoracial identities, and ball status, I sought to include a diverse sample representative of those characteristics. Initially, I determined recruitment for the interviews on a list of “information-rich”27 potential participants developed from recommendations of a Manhattan-based social service agency that has a long history of working directly with the HBC. From this list, I conducted 4 interviews. Following a snowball sampling approach,28 I asked each of these 4 individuals to refer up to 3 additional HBC members to take part in the study. I then recruited a first generation of snowball participants. Repeating this referral process brought a second generation of snowball participants. I conducted interviews until I reached theoretical saturation (i.e., no new gain of information).29

Data Collection

I used in-depth interviews to explore how HIV+ members are treated in the community (both from a lived experience from those who self-identified as HIV+ and from the perception of the treatment of HIV+ members from self-identified HIV-negative participants), to assess how individuals believed HIV affects membership in the HBC, and to examine how the kinship networks of the HBC influence risk behaviors. Interviews were approximately 1.5 hours long, and I conducted them on-site at a local social service agency. I recorded interviews using a digital recorder and entered transcribed documents into an Atlas.ti (Berlin: Scientific Software Development) hermeneutic file.30 HBC members did not receive financial compensation for their participation, which helped to reduce incentivized bias.

Analysis

Guided by the principles of grounded theory,31 I employed an inductive process to analyze the data set. During the first phase of analysis, I used a system of free coding to develop categories of concepts and themes emerging from the data. I also used in vivo codes—verbatim phrases used by the participants (e.g., “shade”)—during this process. An initial inductive analysis process involved discovering patterns and in-case themes to develop a project codebook.27 From these preliminary findings, code names and definitions evolved to match emerging data during iterative analyses of the interviews. That is, using previously identified coding procedures, I reconstructed codes (filling in), expanded on code definitions (extending), collapsed or combined codes (bridging), and added new codes to the list (surfacing).32 I created code families relating to participant characteristics (e.g., “HIV+”) and grouped quotes describing HIV-related stigma in the HBC, either perceived or experienced, into relevant families.

The thematic analysis process included iterative memo-writing steps that documented meaning and rationale for the groupings of emergent themes.33 Ultimately, I framed thematic findings in the concept of moral experience, which I determined to be the most appropriate stigma concept given its focus on social interactions in populations and the role of cultural norms in local worlds.

RESULTS

I conducted 20 in-depth interviews with HBC members who hailed from all 5 of NYC’s boroughs. Table 1 reports self-identified demographics stratified by snowball recruitment generation. Ethnoracial identity, gender identity, informant type, and HIV status are roughly split among the sample. With respect to diversity of ball house representation, the study included 12 individual houses. Qualitative data analysis revealed that HIV-related stigma contributes to a loss of moral experience for HBC members by threatening the connections that HIV+ persons have to others in the community, including ball house, and by posing a threat to attaining ball status. Table 2 is a summary of these findings and illustrates how I translated components of moral experience to understand how HIV-related stigma functions in the HBC. I have given exemplary narratives with reference to relevant themes.

TABLE 1—

Self-Identified Demographics Stratified by Snowball Recruitment Generation: HIV-Related Stigma in the New York City HBC, January–March 2009

| Characteristic | Initial Sample (n = 4), Mean (Range) or No. | First-Generation Snowball (n = 9), Mean (Range) or No. | Second-Generation Snowball (n = 7), Mean (Range) or No. | Total, Mean (Range) or No. (%) |

| Age, y | 33.0 (28–42) | 30.0 (20–44) | 25.0 (18–35) | 28.5 (18–44) |

| Ethnoracial identity | ||||

| Black | 2 | 5 | 1 | 8 (40) |

| Latina/o | 2 | 3 | 3 | 8 (40) |

| Mixed | … | 1 | 3 | 4 (20) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Butch queen | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 (50) |

| Femme queen | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 (50) |

| HIV serostatus | ||||

| Positive | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 (45) |

| Negative | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 (55) |

| HBC ball status | ||||

| Legendary | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 (35) |

| Star | … | 3 | 1 | 4 (20) |

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 (20) |

| Other | 1 | … | 4 | 5 (25) |

Note. HBC = House and Ball Community. The sample size was n = 20.

TABLE 2—

HIV-Related Stigma Resulting From a Loss of Moral Experience in the New York City HBC: January–March 2009

| Component of Moral Experience | HBC-Adapted Component of Moral Experience | Examples |

| Stigma is sociosomatic and moral–emotional, whereby cultural values are tied to an individual’s experience of emotions | Feelings of shame result from physiologic attributes or the loss of status and support | Not competing at balls and fading in and out of the scene because of illness |

| Fear of bringing shame to one’s house because of HIV status | ||

| Internalizing humiliation brought on by not winning competitions | ||

| Stigma is intersubjective, whereby stigma occurs in the space between people at the local level of ascribed words, gestures, meanings, and feelings | Existing in a social world with decreased societal stigmas heightens HIV-related stigma | Experiences of racism, homophobia, or transphobia in home communities |

| Balls are one of few available spaces for marginalized populations in New York City to congregate | ||

| Competition categories derived from gender and class norms increase internalized oppressions | ||

| Stigma threatens what matters most, whereby what is most at stake for individuals (i.e., what they have the most to lose from) in their local world becomes endangered | HIV poses a threat to attain ball status in the community | Spread of shade and gossiping in the HBC because of serostatus |

| Fear of losing respect and recognition after disclosure | ||

| Members usually comfortable disclosing HIV+ status only after obtaining legendary ball status |

Note. HBC = House and Ball Community; HIV+ = HIV−positive. Source. Yang et al.26

Expressed Feelings of Shame

HIV+ participants described instances in which they felt they could not compete at balls or associate with certain HBC members because of their physical appearance associated with HIV. For example, the following participant tells of a time when she internalized feelings of shame and how she believed the shame would be extended to her house if others in the HBC had seen her looking less than her best (or at least her usual self):

Respondent (R): You’ve seen the balls … you know how it goes. It’s all about fashion.

Interviewer (I): So you didn’t walk [in the balls] that year ’cause of your [emaciated] looks?

R: Mmm-hmm … I didn’t want nobody to see me looking haggard. I waited till I was my usual self before coming back [to the HBC]. (femme queen, HIV+)

Other physical attributes associated with HIV described by participants included tiredness, skinniness, weakness, and nausea. Along with feelings of shame in the community owing to personal appearance, most HIV+ participants expressed frustration with wanting to disclose their HIV status, as they believed that the shade in the community would bring a sense of “drama” to their ball house:

R: Even though I wanted to let people know [about my HIV+ status], I couldn’t.

I: What would’ve happened if you started to let people know?

R: No one would talk to me. I wouldn’t be able to walk any balls. All that. It’s messed up. A lot of people assume everyone has it, so the first chance they get to act on it, you’ll see it. I can’t have that kind of drama in my house. (butch queen, HIV+)

In addition to feeling that HIV disclosure could have potential negative consequences to their house, some HIV+ participants believed that members in their house would think less of them. One participant recalls a time when she was suffering from a prolonged bout with pneumonia and felt she had to disclose her status to her house family:

I: So no balls for you during that time?

R: Hell no! You crazy? [laughs]. I kept my ass in bed and did what I needed to do. It’s not always about the balls; sometimes you need to take time out and do you. Because I didn’t get back into the scene until summer, I had to let my children know—that was the hardest part. I think some of them knew already, but to others, I feel like I let them down. (femme queen, HIV+)

As the participant notes, disclosure of HIV status to other HBC members was a concern expressed among many HIV+ participants. Although the initial concern of the impact disclosure was focused on the individual level, HIV+ participants described how their HIV+ status may affect their respective HBC houses. In particular, participants believed that HBC members from other houses would judge and discriminate against their house. This suggests not only that HIV-related stigma affects the individual but also that stigmatization extends to a person’s house. In several situations participants told of narratives in which concealment was a strategy employed to prevent bringing shame to their ball house:

R: How did I tell people [about my HIV+ status]? Girl, that tea [information] was spilled. It was a hot mess! At first I wanted to post [on the Internet] and deny it, but I thought of other people who weren’t afraid to have their tea out… .

I: What happened after? Were people giving you shade?

R: Honey, girls will give you shade whether it’s good or bad news [laughs]. I let it be and let them carry as like however they wanted.

I: So how do you think that affected your ball status, or did it?

R: That was one of my first concerns. You know how it is in the scene. Once people know you have it, no one wants to talk to you; but things seemed to fade out, you know, once the next big piece of news comes along. Really, I wasn’t all that concerned with me. I was worried how shady other girls would be to my house. (femme queen, HIV+)

Because of described shade in the HBC, participants did not want other members to perceive their house as being prevalent with HIV+ members or as having members that engage in risky behaviors (e.g., multiple partners or unprotected intercourse).

Heightening of HIV-Related Stigma

The effect of 1 type of stigma (e.g., gender-based or ethnoracial-based) to either increase or decrease another type of stigma (e.g., HIV-related or sexual) can be operationalized as additive stigma or layered stigma34 and is critical in understanding minority stress.15 Layered stigma results from multiple sources and is associated with personal attributes and behaviors.18 HBC members face various layers of stigma that occur both in and outside their local world. Although HBC members deal with multiple stigmatized identities (e.g., Black and transgender woman, Latino and gay) that can conflict with each other,35 entering the local world of the HBC assists in eliminating these societal stigmas. However the alleviation of those stigmatized identities can increase HIV-related stigma once at an HBC function.

R: Most of my other friends couldn’t deal with me being [HIV] pos—that’s how it was in the ’90s. I guess she [my house sister] was always there though. That’s why I wanted to connect to her house. But still, there’s a lot of shade in the scene, and I always find it hard with everybody knowing about my [HIV+] status. People are always talking. Like trans isn’t an issue. Black isn’t an issue. Gay isn’t an issue. Spanish isn’t an issue. Trade [sex work] isn’t an issue. Femme isn’t an issue. But HIV, now that’s an issue. (femme queen, HIV+)

Unlike other stigmas, HIV-related stigma is not necessarily evident physically and can often be concealed.36 As such, HIV+ members hide their status both in their houses and in the larger HBC to allow them to move up the ball status hierarchy. All participants expressed experiences of perceived discrimination in society (e.g., racism, homophobia, transphobia, or some combination, depending on the context). Narratives of being called “faggot” and “homo” or receiving dirty looks when walking down the street or on the subway were common. Many butch queens, all of whom identified as gay men, told of instances in which they felt racism in the local NYC gay community and of not fitting the “Chelsea boy mold” (i.e., stereotypical young, White, seemingly affluent, fit men living in the Chelsea neighborhood).

R: I don’t like gay clubs. Even the ones for us.

I: What do you mean “for us?”

R: Like for Blacks and Latinos. It’s like if it wasn’t for the balls, I wouldn’t even go out. I hate dealing with Chelsea boys. Most of them aren’t even from here. They’re from the Midwest or some jacked up place and now they come here and think they’re badass. Those aren’t my people. (butch queen, HIV+)

The HBC balls have historically been one of the few places where ethnoracial and sexual minority youths in NYC can turn for acceptance, which increases familial bonds among house members and the larger HBC. However, because the HBC creates a homophobic-free and transphobic-free space for ethnoracial minorities, any deviation could result in possible HIV-related stigma.

Threats to Attaining Ball Status

Although Figure 1 depicts a solid movement through status titles, real-life nuances exist in creating and establishing ball status. The most notable difference is the self-reported status of an individual versus the status perceived from other community members. For example, individuals may believe that they have progressed to “legendary” status, whereas the general consensus of the HBC could be that they are still “up-and-coming.” As there are no set standards for obtaining ball status (e.g., winning 3 competitions per year for 2 years to advance), ball status is affected by 2 main factors: individuals’ ability to promote themselves and other HBC members’ acknowledgment of their self-proclaimed status titles. Because ball status is so heavily regarded in the HBC (it is what is most at stake in their local world), individuals are quick to amass ball status once becoming indoctrinated into the HBC. All participants perceived HIV as a barrier to achieving ball status.

R: You know, I try not to hook up with people in the balls … it’s like, you know, all the shade? I hear of lots of things about the [HIV] rates in the community … and that’s just not something I need right now.

I: A relationship?

R: Maybe that. But the kitty [HIV]. I hear lots of stories of how everybody have it and nobody’s saying anything. I want to be legendary … I want to have a future and I can’t have one with all that. (butch queen, HIV negative)

Indeed, all participants expressed that if they were to be known to be HIV+ early in their ball career their progression to legendary status was highly unlikely. As a result, many in the HBC conceal their HIV+ status for fear of losing recognition. Every participant mentioned that it was the “shade” in the community that fosters secrecy of HIV status in the HBC and prevents individuals from supporting their HIV+ counterparts. In fact, it was mentioned that HIV+ members will also “throw shade” and stigmatize other HIV+ members in an effort to prevent them from moving up the ball status hierarchy.

I: So do people in your house know you’re [HIV] positive?

R: Very few, I would say. It’s something I really don’t get into with them.

I: Why’s that?

R: Girl, it’s the shade! They might be my house and all, but you know, one slip then somebody’s telling someone who’s telling someone who’s telling someone. I’m trying to move up [in the HBC] and with all the shade, that’s not gonna happen. Besides, it’s my business. (butch queen, HIV+)

Interestingly, a finding that is seemingly counter to other results revealed that in addition to serving as role models for younger HBC members, legendary members serve as role models for each other and more established community members even if they are known to be HIV+:

R: I’ve always been secretive about having it [HIV]. Like, sometimes I wouldn’t tell boyfriends because I knew word would get around. I thought they would throw shade, but once my house knew they were nice about it. But then, I am their father [laughs].

I: So you think if you weren’t the housefather that it would’ve ended up differently?

R: Probably. Like, there’s always stories of people getting shade after people find out. Then there’s people like Geo [an alias; another legendary HIV+ housefather], where everybody know his business and it’s ok.

I: Kinda like role models?

R: Yeah, just like that. I think the more open people become, the more open others become to accepting. (butch queen, HIV+)

The only participant to have attained a graduate degree likened having legendary status in the HBC to professors in academia who have attained tenure. As she explained, “Once you’re at the top, it doesn’t matter what others say” (femme queen, HIV negative). Only after being recognized as having legendary ball status were HIV+ individuals more likely to receive accolades from others within the HBC.

DISCUSSION

To my knowledge, this study is the first qualitative academic work to contextualize the role of HIV-related stigma in the NYC HBC. Results revealed that the effect of HIV in the HBC extends beyond traditional health outcomes and that HIV affects social structures that affect the overall well-being of an individual as well as the social norms and cultural values in the local world of the community. Operationalized as a loss of what is most important for an individual, moral experience factors into the HBC in terms of both a loss of ball status attainment and a loss of social and emotional support for HBC members. HBC house families serve as both a refuge from and a source of stigma, as houses are idealized as a place of unconditional love and acceptance. In fact, however, the houses are part of a larger HBC that sustains intense competition for acceptance and love that is, in part, derived from how well house members meet certain expectations. The loss of social standing resulting from HIV-related stigma through shame and humiliation contradicts the founding values of the HBC, which were to include individuals looking to escape societal stigmas.

The results present nuanced understandings of how HIV-related stigma functions in social interactions among a disproportionately affected population of urban ethnoracial and sexual minorities. Because of the pervasiveness of shade in the HBC, HIV+ members not only are stigmatized by non-HIV+ persons but also act as stigmatizers to fellow HBC members, including those in their own house, in an effort to sustain their social position or to prevent others from gaining ball status recognition. HBC balls provide literal spaces for these individuals to congregate and create their own local world that defines, redefines, and, in some cases, reinforces societal class, gender, and race lines. As such, the competitive nature of the HBC produces inherent jealousy and self-defeating alliances among the population, and the intricate ball categories can increase physiological stressors, such as internalized homophobia and racism, which are known to influence sexual risk-taking behaviors.37 An important study finding was that although HIV stigma can result as a loss of moral experience, achievement of legendary status (i.e., recognition in the HBC) can serve as a protective factor to the potential disconnection of social ties in the local world of the HBC.

Limitations

The study sample included a mix of HIV+, HIV-negative, younger, older, and ethnoracially diverse individuals. As such, the findings present both variation and commonality in the viewpoints and experiences expressed. Still, there exist several study limitations. First, the NYC HBC is a select population, and findings may not be generalizable to other, non-NYC HBCs or minority populations. That is, regional cultures of HBCs (e.g., in Chicago and Atlanta) may present nuanced characteristics other than those found in the population. Second, cultural group differences in the use of moral experience, which was originally developed on the basis of mental illness in China, may reshape how the concept is experienced in these distinct cultural groups. This is particularly true as HIV-related stigma is viewed as morally discrediting and, as is the case with the NYC HBC, can be even more threatening in a socially discredited population existing in a local world that acts as both support and competition. Third, there is a lack of analysis surrounding gender and sexuality constructs in relation to competition categories, most notably among transgender (i.e., femme queen) persons. Fourth, in exploring risk behaviors, the study might have benefited from a detailed discussion of injection use (particularly, hormone use among femme queens) or the exploration of drug use patterns in relation to sexual risk. Finally, this study could have been strengthened with a mixed methods approach or the inclusion of other data sources (e.g., by triangulating participant observation logs, field journals, and focus groups, or by having survey data).

Implications

With respect to future studies that focus on the HBC, I put forth the following recommendations: a descriptive mapping of the HBC to better gauge the size of the HBC (including number of houses and number of people in each house), a comparison of HBCs in other states and regions, longitudinal studies of individual house members, and an implementation of a stigma-focused intervention in the community. Whereas previous work with the HBC has focused on traditional HIV prevention paradigms (e.g., condom use and testing), in considering how social service agencies may intervene with the HBC in the future, I recommend that programs be designed that aim to reduce HIV-related stigma by lessening threats to moral experience. A significance of the house structure of the HBC is that it has the potential to support community members in the face of HIV.38 Influential individuals in a community are usually considered popular opinion leaders and are seen as catalysts for information distribution and behavioral influence.11–13 Housemothers, -fathers, and legends in the local world of the HBC are role models who have the agency to champion interventions that prevent a loss of moral experience for their fellow HBC members. Although HBC houses provide much needed social and material support in a world of societal stigmas (e.g., homophobia, transphobia), HBC members are concurrently forced to deny or conceal their HIV status or risk being rejected and cut off from these material and emotional support systems. Providers should reflect on their work with the HBC to enhance services that lessen threats to moral experience, and academics should realize the potential for addressing health disparities and gender constructs among a population of marginalized individuals in an urban setting.

Acknowledgments

The University of California, San Francisco Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, Traineeship in AIDS Prevention Studies (TAPS) Program supported dedicated time to write this article (grant NIMH T32 MH019105).

Sincere gratitude goes to Patrick A. Wilson, Theo G. Sandfort, Joyce Hunter, Debra S. Kalmuss, and Miguel A. Muñoz-LaBoy of the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University as well as Rafael M. Diaz, Karen Tu, and Brynn Saito for their support and insights during the data analysis process. The author would like to express his deepest appreciation to the study participants, who generously gave their time in support of this project. Finally, the author would like to acknowledge the significant input from his TAPS program directors and fellow TAPS scholars.

Human Participant Protection

The Columbia University Research Compliance and Administration System approved all human participant procedures (IRB-AAAD1825). I obtained verbal informed consent from the study participants.

References

- 1.Galindo GR. Stigma, Status and Support: Exploring the Treatment of HIV+ Members and Social Service Agency Involvement Within the New York City House and Ball Community [dissertation]. New York: Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galindo GR. History and description of the New York City House and Ball Community: implications for public health interventions. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality; November 4–7, 2010; Las Vegas, NV.

- 3.Murrill CS, Liu KL, Guilin Vet al. HIV prevalence and associated risk behaviors in New York City’s House Ball Community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1074–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene HIV Epidemiology Program. 1st Quarter Report. 2006;4:1 Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/dires-2006-report-qtr1.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene New HIV Diagnoses Rising in New York City Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. Young Blacks and Hispanics Hit Hardest. Press release no. 079-07; 2007. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2007/pr079-07.shtml. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6. San Francisco Department of Public Health. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Annual Report. HIV Epidemiology Section; 2010. Available at: http://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/reports/RptsHIVAIDS/AnnualReport2010.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 7.County of Los Angeles. Public Health. HIV Epidemiology Program; 2011 Annual HIV Surveillance Report. 2011; Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/wwwfiles/ph/hae/hiv/2011_Annual%20HIV%20Surveillance%20Report.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 8. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New York City Annual HIV/AIDS Surveillance Statistics 2009. HIV Epidemiology and Field Services Program; 2009. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/surveillance2009_tables_all.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012.

- 9.Miami-Dade County Health Department HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report; 2010. Available at: http://www.dadehealth.org/hiv/HIVsurveillance.asp. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene New HIV (non-AIDS) diagnoses among young men who have sex with men, New York City, 2001–2008 NYC DOHMH HIV Epidemiology and Field Services Program Semiannual Report. 2009;4(1):1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group Selection of populations represented in the NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial. AIDS. 2007;21(suppl 2):S19–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Detels Ret al. Selecting at-risk populations for sexually transmitted disease/HIV intervention studies. AIDS. 2007;21(8):S81–S87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JA. Popular opinion leaders and HIV prevention peer education: resolving discrepant findings and implication for the development of effective community programmes. AIDS Care. 2004;16(2):139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Murrill C, Guilin V, Dean L. Risk behaviors and psychosocial stressors in the New York City House Ball Community: a comparison of men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity New York: Simon and Schuster; 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Link B, Phelan J. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman A. What Really Matters: Living a Moral Life Amidst Uncertainty and Danger Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):157–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herek GM. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: theory and practice. J Soc Issues. 2007;63(4):905–925 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayala G, Beck J, Lauer K, Reynolds R, Sundararaj M. MSMGF Policy Brief: Social Discrimination Against Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM)—Implications for HIV Policy and Programs. The Global Forum on MSM and HIV; 2010. Available at: http://www.msmgf.org/index.cfm/id/11/aid/2106. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phelan JC, Link BC, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: one animal or two? Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):358–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford AM. Stigma associated with AIDS: a meta-analysis. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1996;26(5):398–416 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang LH, Kleinmam A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(7):1524–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckathorn DD. Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2011;41(1):355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muhr T. Atlas.ti for Windows. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deacon H. Towards a sustainable theory of health-related stigma: lessons from the HIV/AIDS literature. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16(6):418–425 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson PA. A dynamic-ecological model of identity formation and conflict among bisexually-behaving African-American men. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(5):794–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Comulada S, Weiss R, Ramos ME. Predictors of HIV-related stigma among young people living with HIV. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):501–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Díaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(3):255–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnold EA, Bailey MM. Constructing home and family: how the Ballroom Community supports African American GLBTQ youth in the face of HIV/AIDS. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2009;21(2):171–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]