Abstract

Herpesviruses assemble large virions capable of delivering to a newly infected cell not only the viral genome, but also viral proteins packaged within the tegument layer between the DNA-containing capsid and the lipid envelope. In this review, we describe the tegument transactivator of the β-herpesvirus human CMV, the pp71 protein. We present the known mechanistic features through which it activates viral gene expression during a lytic infection but fails to do so when the virus establishes latency, and describe how pp71 stimulates the cell cycle and may help infected cells avoid detection by the adaptive immune system. A historical overview of pp71 is extended with current perceptions of its roles during human CMV infections and suggestions for future avenues of experimentation.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, HCMV, herpesvirus, pp71, tegument

Human CMV (HCMV) is a β-herpesvirus that infects a majority of the world’s population. Much of its success as a human pathogen can be attributed to its ability to persist despite intense immune surveillance and attack. HCMV-induced morbidity generally only presents in patients with immature, compromised or suppressed immune function, but infections are never cleared even from healthy, immune-competent patients [1].

At least one component of the HCMV arsenal of immune evasion tactics is to enter a nonproductive state of latency [2,3]. Productive, lytic infection is the process by which infectious progeny virions are produced and spread. This requires the synthesis of a substantial number of viral gene products that can be prime targets for both antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses. During latency, only minimal viral gene expression occurs, allowing the virus to go undetected by the immune system. Periodically, HCMV reactivates from this latent state to produce progeny virions that allow for spread within the host or to new hosts [4]. Although lytically infected cells, such as fibroblasts, die within a few days, it is currently unclear how long a latently infected cell can survive in vivo. HCMV is known to establish latency in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells [5–8], which are known to be long lived in mice [9]. The lifespan of human CD34+ cells, infected or uninfected, remains unknown.

HCMV is an enveloped, dsDNA virus. The genome is approximately 235 kb and is divided into two main regions – the unique long (UL) and unique short (US) – each of which is flanked by a series of repeats [4]. HCMV encodes at least 166 and as many as 200 open reading frames [10]. Virions consist of a genome packaged within a protein capsid, which in turn is protected by a lipid envelope. Found between the capsid and envelope is a proteinaceous layer, known as the tegument, which is a defining structural feature of herpesvirus virions. Although composed mainly of viral proteins, cellular proteins, as well as cellular and viral RNAs, are present in the tegument. Components of the tegument begin to modulate the cellular environment immediately upon viral entry, even prior to the initiation of viral gene expression. Known activities of tegument proteins include immune evasion, transport of the capsid to the nucleus, cell cycle modulation and, most notably, activation of viral gene expression [11].

The HCMV lytic gene expression cascade is temporally regulated. Immediate early (IE) genes are the first to be expressed. The IE proteins then activate expression of early and late genes. Early proteins are required for DNA replication and late proteins are primarily structural components of the virion [4]. Failure to express IE genes results in the silencing of the majority of viral genes. This silencing must occur for the virus to properly establish latency. The main tegument transactivator that activates HCMV gene expression and promotes commitment to lytic replication is the pp71 protein [12,13], which is encoded by the UL82 gene [14].

Nomenclature

The protein composition of HCMV particles was analyzed by SDS-PAGE in 1975 and 23 individual species were identified and labeled numerically as virion proteins (VPs). The protein migrating at an estimated molecular weight of 75 kDa was named VP8 [15]. By 1983, this protein was described as a 74-kDa phosphorylated matrix protein, indicating that it had been defined as a component of the tegument [16]. Shortly thereafter, a study characterizing monoclonal antibodies directed against HCMV virion components used the term ‘pp71’ (for 71-kDa phosphoprotein), giving the protein its most common and currently favored name [17], although it can also be found referred to as the upper matrix protein [18]. Complete sequencing and subsequent computational analysis of the protein-coding capacity of the AD169 laboratory-adapted strain of HCMV revealed that the gene encoding pp71 was located in the 82nd open reading frame within the UL region of the genome, and was therefore named UL82 [14]. Thus, pp71 is sometimes referred to as ppUL82 [19], for the phosphoprotein encoded by the UL82 gene.

Expression

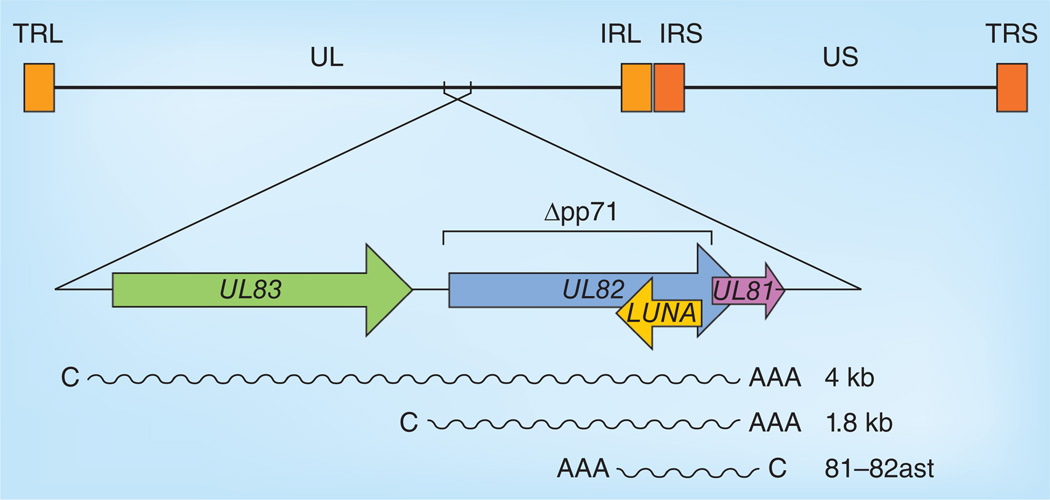

Early work localized the HindIII restriction fragments capable of producing pp71 to map units 0.510–0.530. Another tegument protein, pp65 (lower matrix protein; ppUL83), was also mapped to this region, which was found to generate two mRNAs of 4 and 1.8 kb in length [20]. It was later determined that the 4-kb mRNA was bicistronic, encoding first pp65 (UL83), followed by pp71 (UL82), and that the 1.8-kb mRNA represented a 3´ coterminal segment of the larger species encoding only pp71 (Figure 1) [21]. Recent high-resolution transcriptome analysis failed to detect any substantial deviations from this previously reported expression pattern [22].

Figure 1. The UL82 locus.

Schematic diagram of the prototypic human CMV genome with an expansion of the region surrounding UL82 (shown, for simplicity, in reverse orientation to its arrangement in the genome). Annotated open reading frames are shown as block arrows. mRNAs are shown as wavy lines with a C and a AAA, with their size is indicated in kilobase pairs. The deletion made in UL82 to construct the pp71-null virus is indicated.

AAA: 3´ poly-A tail; C: 5´ cap; IRL: Internal repeat long; IRS: Internal repeat short; TRL: Terminal repeat long; TRS: Terminal repeat short; UL: Unique long; US: Unique short.

Also encoded within this genomic locus is a transcript initiating from the opposite strand that runs antisense to UL82 and UL81 (Figure 1), known as UL81–82ast [23]. UL81 is a small open reading frame that has the potential to encode a 116-amino acid protein [14], but is likely noncoding, as it lacks an ATG start codon and is not conserved in chimpanzee or rhesus CMVs [24]. It has been speculated that UL81–82ast may function as a noncoding RNA, perhaps during latency, to post-transcriptionally downregulate pp71 protein accumulation by decreasing the stability or translatability of pp71-encoding RNAs. To date, no experimental evidence supports this hypothesis, although the potential for antisense suppression of pp71 expression appears real [25], and UL81–82ast appears to be expressed during both natural and experimental (in vitro) latent infections [23,26,27]. Transcripts antisense to major HSV-1 transactivator proteins have been shown to encode miRNAs capable of curtailing the expression of the protein on the opposing strand [28]. However, bioinformatics tools combined with northern blot analysis failed to identify miRNAs encoded by UL81–82ast [sullivan c, kalejta r, unpublished data]. UL81–82ast encodes a protein named LUNA that appears to be expressed in vivo, as it is recognized by antibodies from HCMV-infected patients [26] and can be detected in vitro during lytic infection of fibroblasts [23]. Expression of LUNA during latency has not been examined. Functions of the LUNA protein or its potential roles during HCMV infection have not been described.

During lytic infection, pp71 is expressed with early/late kinetics [19]. Many viral proteins, such as pp71, are expressed to high levels late in infection, but do not have the requirement of DNA replication for their expression, and thus are referred to as early/late genes. pp71 is not expressed during latency, and its transcript was detected after those from the major IE locus during induced reactivation of experimental latency in vitro [27].

Structure

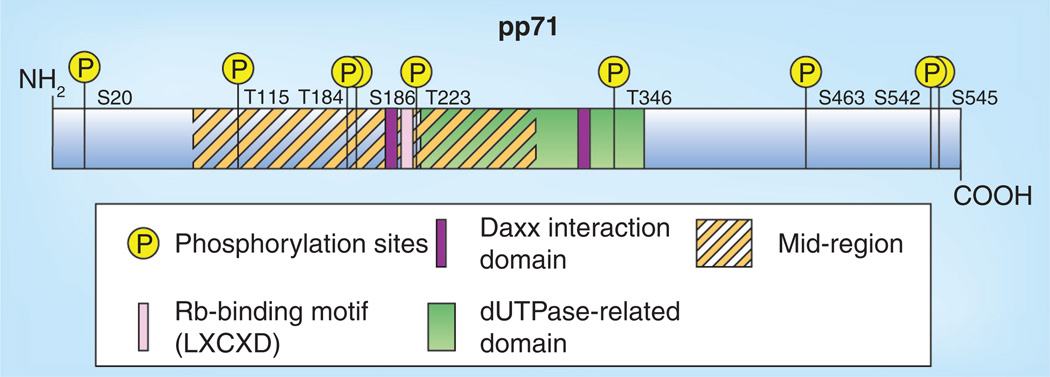

No structural information for pp71 exists. Protein sequence comparisons of pp71 with herpesviral and cellular genes revealed a domain with similarity to 2´-deoxyuridine 5´-triphosphate pyrophosphatase, otherwise known as dUTPase (Figure 2). Thus, pp71 has been described as a dUTPase-related protein with a dUTPase-related domain, and there are approximately 20 similarly classified human herpesvirus proteins [29]. It is speculated that an ancestral herpesvirus acquired a cellular dUTPase, and over time, the genes have undergone duplications and divergence. In most instances, the dUTPase catalytic residues are absent, and thus these dUTPase-related proteins are generally inactive. While the dUTPase-related domain likely represents a structural scaffold for pp71, this hypothesis has not been explored experimentally.

Figure 2. Sequence features of pp71.

A linear representation of the 559-amino acid pp71 protein. Locations of the known post-translational modification (i.e., phosphorylation) sites are indicated (S and T). Domains of the protein representing a likely structural scaffold (dUTPase-related domain, amino acids 266–365) or controlling subcellular localization (mid-region, amino acids 94–300) are indicated. Motifs that mediate the interactions with Daxx (Daxx interaction domain 1, amino acids 206–213; Daxx interaction domain 2, amino acids 324–331) and the Rb family proteins (LXCXD, amino acids 216–220) are also depicted.

Rb: Retinoblastoma; S: Serine; T: Threonine.

Interactome

Multiple methods to identify binding partners for pp71 have been employed, including yeast two-hybrid screening, coimmunoprecipitation with western blotting (IP-WB) and mass spectrometry (MS). Detecting pp71 interactors in human cells can be challenging, as pp71 is known to induce the degradation of at least a subset of the proteins to which it binds (see below). Nevertheless, identification of pp71-associating proteins has been instrumental in deciphering much of what is known mechanistically about how pp71 functions. Here, we highlight pp71-interacting proteins and the methods used to define them. Discussion of the significance of these interactions is left to subsequent sections of the manuscript.

The first protein shown to interact with pp71 was the cellular Daxx protein, a histone H3.3 chaperone [30] and transcriptional corepressor [31] that recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) to targeted promoters and represses transcription. This interaction was first detected by yeast two-hybrid screening [32]. Its observation was instrumental in deciphering the mechanism through which pp71 promotes viral gene expression (see below). There appears to be two regions of Daxx that interact with pp71: an N-terminal region [32,33] and a central, glutamine-rich domain [32]. Similarly, two regions of pp71 have affinity for Daxx. These short motifs (amino acids 206–213 and 324–331) have some homology to the previously mapped Daxx interaction domain (DID) of the CENP-C protein, and thus have been named DID1 and DID2, respectively (Figure 2). Deletion of either of these motifs abrogated Daxx binding, but individual alanine substitution mutants retained binding ability [32].

Shortly after the Daxx interaction was uncovered, the observation that pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression and the identification of a near-canonical retinoblastoma (Rb) protein-binding motif (with the sequence LXCXD (Figure 2), where X stands for any amino acid) led to the demonstration by IP-WB that pp71 interacts with all three Rb family members [34]. Very recently, a bevy of host cell proteins were identified in complex with pp71 by MS [35]. Included among these was BclAF1, the only interaction from the list verified by IP-WB. Pathway analysis using BiNGO [36] indicates that gene expression, actin-based motility, RNA processing and ribosome biogenesis are biological processes that may be influenced by pp71. While the ability of the protein to modulate gene expression is well established (see below), whether or not pp71 affects the other processes implicated by the ontology analysis of its interactome awaits further experimentation. Interestingly, Daxx and the Rb proteins were not found to be associated with pp71 in these pull-down MS experiments, implying that they were not comprehensive, and that our catalog of known or candidate pp71-interacting proteins is likely to be incomplete. In addition to these cellular proteins, pp71 has also been shown to interact with several viral proteins, including UL32 (pp150), UL35 [37] and UL94 [38,39]. The functional significance of these interactions has not been explored.

Localization

The subcellular localization of pp71 is affected by several factors, including whether the protein is tegument-delivered or nascently expressed, the differentiation status of the infected cell (incompletely vs fully differentiated) and the time after infection (early vs late). When HCMV infects differentiated cells that are permissive for lytic replication, such as fibroblasts, tegument-delivered pp71 protein accumulates in the nucleus [19]. At these pre-IE times, pp71 can be observed in discrete spots within nuclei that correspond to promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs) [33,40]. Localization to PML-NBs is dependent upon the ability of pp71 to associate with Daxx [33]. As infection proceeds, Daxx levels decrease due to pp71-mediated degradation (see below) and pp71 levels increase as de novo synthesis occurs, resulting in a pan-nuclear localization of pp71. At late times during infection, pp71 is further redistributed to the cytoplasmic assembly compartments [19,41], which are found immediately adjacent to the nucleus, where it is packaged into virions.

When HCMV infects incompletely differentiated cells (henceforth referred to as undifferentiated) where latency will be established, such as CD34+ cells, tegument-delivered pp71 accumulates in the cytoplasm [42–44]. Interestingly, de novo-expressed pp71 (by plasmid transfection or recombinant adenoviral transduction) accumulates within the nuclei of these cells at PML-NBs. Thus, undifferentiated cells are competent at transporting pp71 to the nucleus, except when it is delivered by infecting virions.

Pieces of information have emerged as to how pp71 localization is regulated, but detailed mechanistic information remains elusive. Computational searches have failed to identify a canonical nuclear localization signal within the 559-amino acid protein. The smallest fragment that can be attached to GFP and promote its nuclear localization was determined to be amino acids 94–300. This domain is referred to as the mid-region (MR) [41]. The requirement of such a large fragment suggests that the MR (Figure 2) may mediate binding to a cellular protein or complex that is responsible for nuclear transport of pp71. This, in fact, is the case for the HSV-1 tegument transactivator, VP16, which must associate with cellular HCF-1 to enter the nucleus [45]. Why this hypothetical, critical interaction does not occur or is nonfunctional for tegument-delivered pp71 in undifferentiated cells is unclear. Perhaps the ability of the tegument to disassemble properly in undifferentiated cells is compromised, and the interaction surface required for nuclear import remains masked. Such a model is bolstered by the observation that the tegument-delivered pp65 protein travels to the nucleus in differentiated cells, but similar to pp71, remains cytoplasmic when the virus latently infects undifferentiated cells [42]. As cytoplasmic localization of a normally nuclear tegument protein during infection of undifferentiated cells is not pp71-specific, mislocalization under these circumstances may be more generalized to the tegument as a whole, and thus indicative of a disassembly defect. The observation that tegument-delivered pp71 and pp65 appear to colocalize in the cytoplasm of undifferentiated cells [penkert r, kalejta r, unpublished data] further supports the notion of a defect in tegument disassembly, as these two viral proteins do not appear to directly interact [38,39].

Phosphorylation has also been implicated in modulating the subcellular localization of pp71 expressed from transfected plasmids. Nine phosphorylation sites on pp71 have been cataloged (Figure 2) [41], but the kinases responsible for phosphorylation have not been identified. One phosphorylation site, threonine 223, which is located in the MR, might control pp71 subcellular localization. An alanine substitution mutant (T223A) mimicking an unphosphorylated residue still localizes to the nucleus. However, a phosphomimetic substitution mutant (T223D) is cytoplasmic [41]. Thus, phosphorylation at this site clearly has the potential to regulate pp71 subcellular localization. The fact that pp71 is phosphorylated in the virion [16,18] suggests a model in which nuclear pp71 is phosphorylated at T223 late during infection to promote export to the cytoplasm and virion incorporation, and becomes dephosphorylated upon entry into differentiated cells (but not undifferentiated cells) to promote nuclear localization. However, phosphatase inhibition with okadaic acid failed to inhibit tegument-delivered pp71 from reaching the nucleus in fibroblasts [penkert r, kalejta r, unpublished data]. Thus, either this model is incomplete or an okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase is responsible for dephosphorylation. Whether or not this residue in fact modulates pp71 subcellular localization during lytic or latent infections awaits the generation and analysis of recombinant viruses that express these mutant alleles of pp71.

Finally, it is now clear that the inability of tegument-delivered pp71 to translocate to the nuclei of undifferentiated cells results from a missing function within these cells, and not from a dominant block. In heterogeneous fusions of differentiated and undifferentiated cells, tegument-delivered pp71 was efficiently transported to the nucleus, indicating that undifferentiated cells lack a factor that is required for pp71 nuclear import that was provided by the fibroblast cells in the heterokaryons [42]. In light of the data discussed above, such a differentiated cell factor may be a phosphatase, some other enzyme that could break apart tegument protein complexes (such as a kinase or protease) or a nonenzymatic protein that can promote tegument disassembly. It is important to note that pp71 may not be the direct target of this putative factor, but its ultimate effect may include the liberation of the MR surface of pp71 for protein binding, or the unmasking of threonine 223 for dephosphorylation.

Transactivation

Knowing that a virion component activated IE gene expression [46,47], a candidate approach identified pp71 as a tegument transactivator of the viral major IE promoter (MIEP) [13]. This was a fundamental advance towards deciphering the mechanism through which HCMV IE gene expression is controlled. Reporter assays identified ATF and AP-1 sites as mediators of pp71 transactivation, both in the context of the MIEP as well as synthetic promoters [13]. A similar candidate approach discovered the ability of pp71 to increase the infectivity of transfected HCMV DNA [48]. Surprisingly, considering that pp71 activates the MIEP, expression plasmids for neither the entire MIEP locus nor for the most abundant proteins derived from this locus (IE1 and IE2) were able to significantly increase the infectivity of transfected viral genomic DNA [48]. While the IE proteins are assumed to play a role in this enhancement of infectivity, these experiments demonstrate that pp71 apparently has additional viral (or cellular) targets that are critical to this activity. Despite the incomplete mechanistic understanding at the time, cotransfection of a pp71 expression plasmid became, and continues to be, a standard protocol when generating recombinant, infectious virus from transfected viral genomes, such as those carried on the bacterial artificial chromosome clones now commonly used for HCMV mutagenesis [49,50].

Additional transfection assays showed the ability of pp71 to enhance the expression of the HCMV US3 [51] and US11 [52] genes. Furthermore, pp71 has been shown to activate the expression of HSV-1 [53,54] and adenovirus genes [53], indicating that the influence of pp71 extends beyond the HCMV genome. Effects of pp71 on cellular gene expression have not been directly analyzed. Note that some of the assays described above use artificial systems to assay for pp71 transcriptional transactivation and thus it remains to be determined whether these activities are physiologically relevant in the context of viral infection.

Genetics

The initial indication of the necessity for UL82 (pp71) for efficient HCMV replication came serendipitously through experiments designed to assess the requirement for UL83 (pp65) during lytic infection. pp65 expression was down-regulated by two independent mechanisms: deletion of the UL83 gene [55] or expression of an antisense UL83 cDNA [25]. While the pp65-null virus grew with wild-type kinetics, wild-type virus replication in cells constitutively expressing the UL83 antisense cDNA was inhibited. IE gene expression occurred normally, but viral DNA replication, late gene expression and progeny virion production were severely impaired in these cells [25]. Interestingly, these defects were not observed upon infection with the pp65-null virus, indicating that the antisense transcript was not having ‘off target’ effects. Detailed investigation revealed that the UL83 antisense cDNA inhibited accumulation of the bicistronic 4-kb mRNA, which encodes both pp65 (UL83) and pp71 (UL82), and consequently decreased levels of both proteins. The pp65-null virus lacked the targeted sequence and hence pp71 expression was unaffected. This overlooked study is important for two reasons. First, it provides compelling data that the 4-kb bicistronic mRNA is translated to produce both pp65 and pp71. Second, it indicated that pp71 is required for efficient viral DNA replication. As tegument-delivered pp71 was unaffected in this study, no inhibition of IE gene expression was observed using this approach (see below).

More direct evidence for the requirement of pp71 for efficient replication came from the analysis of a pp71-null virus [12]. Isolation of this mutant required growth on a complementing cell line that produced pp71 in trans. In these cells, the ectopically expressed pp71 is incorporated into viral particles, meaning that the virions released from these cells contain pp71 protein in the tegument, but lack the pp71 gene (UL82) in their genomes. Passage of such stocks once at high multiplicities through noncomplementing cells generates pp71-null virions that also lack pp71 in the tegument. Such stocks can also be created by growing pp71-null viruses on Daxx-knockdown cells (see below). Single-step (high-multiplicity) growth curves indicated that pp71-null viruses lacking tegument pp71 had a 100-fold growth defect. Mutant viruses grown on complementing cells with pp71 packaged in the tegument showed only a tenfold defect. This appeared to indicate that pp71 promotes HCMV infection at two independent steps, only one of which is performed by the tegument-delivered protein. Multistep growth curves revealed a 10,000-fold growth defect, showing the strict requirement for pp71 at low multiplicities [12].

Phenotypic analysis indicated that pp71-null viruses had severe defects in the accumulation of IE genes, including IE1 and IE2 (transcription factors), UL37x1 and UL38 (antiapoptotics), UL106–UL109 (the 5-kb RNA) and UL115–UL119 (glycoproteins). Reduced viral DNA replication and late gene expression were also observed, but it is unclear whether these events are directly impacted by pp71 or if the observed defects are secondary to decreased IE gene expression. Experiments in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide indicated that tegument-delivered pp71 was responsible for promoting the expression of the IE genes [12]. This landmark technical achievement of generating and trans-complementing a pp71-null virus (prior to the time of bacterial artificial chromosome mutagenesis) provided physiologic significance to earlier transfection studies, and firmly defined pp71 as a tegument transactivator.

Subsequent genetic analysis went on to show that it was the ability of pp71 to interact with Daxx that was critical for its transactivation function. Recombinant viruses expressing either of the DID mutants in place of wild-type pp71 showed phenotypes that were similar to pp71-null viruses, with defects in IE gene expression and productive replication [56]. Thus, the pp71 protein stimulates IE gene expression through its interaction with the cellular Daxx protein.

Further genetic analysis explored the requirement for Rb family member inactivation by pp71 (see below). A recombinant virus expressing a pp71 mutant unable to induce the degradation of Rb family members grew with wild-type kinetics [56], indicating that Rb degradation induced by pp71 was dispensable for virus replication. Since that time, it has been discovered that the viral UL97 protein also mediates Rb inactivation, in this case through direct phosphorylation [57]. Thus, the redundancy of Rb-targeting proteins encoded by HCMV may explain, in part, why Rb family member degradation by pp71 is not required for lytic replication in fibroblast cells in vitro.

De-repression

While the necessity of the pp71–Daxx interaction for IE gene expression had been established, the mechanism through which this occurred remained unknown. Independent work (see below) had discovered that pp71 induced the proteasomal degradation of the Rb family of tumor repressors [34,58]. Extending that work, a critical breakthrough occurred when it was observed that Daxx levels dropped precipitously after HCMV infection of fibroblasts [59]. This was shown to occur through a process that required proteasome function and tegument-delivered pp71. Inhibition of the proteasome with lactacystin prevented IE gene expression upon HCMV infection, unless either HDACs were inhibited or Daxx levels were reduced by RNAi approaches [59].

Subsequent experiments demonstrated that Daxx knockdown in semipermissive U373 cells permitted IE gene expression after infection with a pp71-null virus [60,61], and rescued viral growth [60]. Furthermore, U373 derivatives that overexpress Daxx were refractory to wild-type HCMV infection [60,62]. Congruent with the ability of HDAC inhibitors to rescue IE gene expression under conditions of Daxx stabilization [59], knockdown of Daxx increased the acetylation of histones (a mark of transcriptional activity) associated with the viral MIEP early after infection [62].

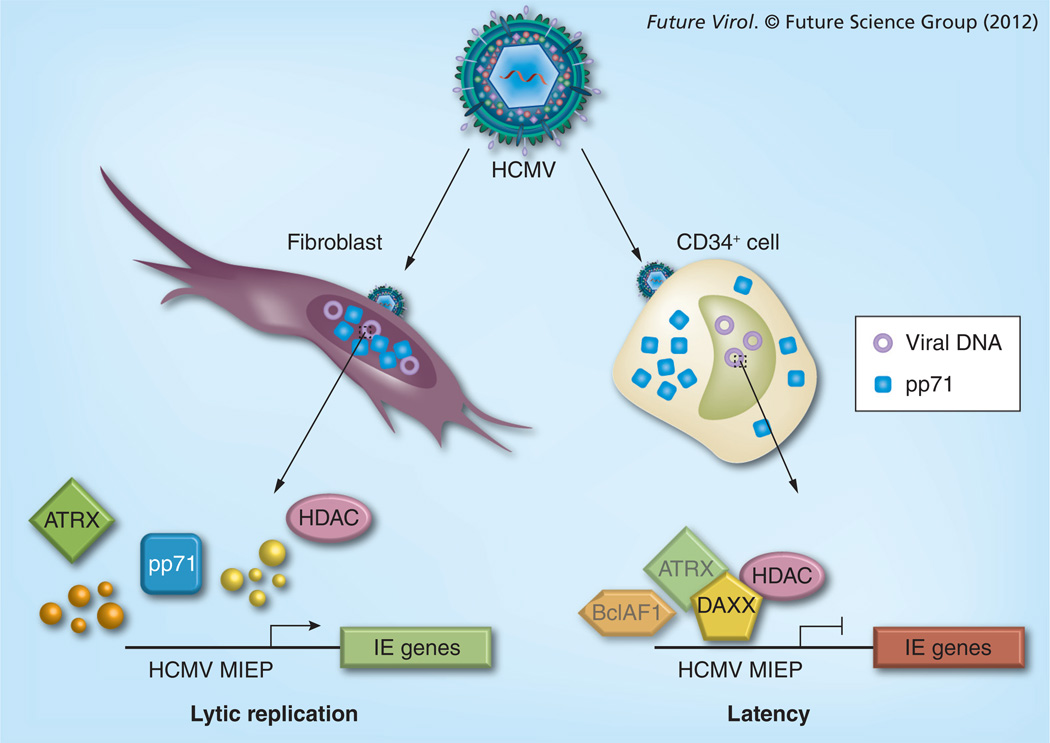

These series of experiments performed by multiple, independent groups, led to a model (Figure 3) describing the molecular events that preceded IE gene expression (called the pre-IE stage) during lytic infection of fibroblasts [63]. Viral genomes entering the nucleus are transcriptionally silenced by an intrinsic cellular defense [59] mediated by the Daxx protein that establishes a repressive chromatin structure on the MIEP. The migration of tegument-delivered pp71 to the nucleus and the subsequent degradation of Daxx relieve this repression to promote IE gene expression. Thus, the HCMV tegument transactivator is really a tegument de-repressor.

Figure 3. The subcellular localization of tegument-delivered pp71 influences the outcome of viral infection.

Upon entry, HCMV virions (top) introduce tegument proteins into infected cells. In differentiated cells such as fibroblasts (left), tegument-delivered pp71 enters the nucleus and induces the degradation of Daxx and BclAF1, and displaces HDACs and ATRX. This inactivates the intrinsic defense instated by these proteins, activates IE gene expression and initiates productive, lytic viral replication. In undifferentiated cells such as CD34+ cells (right), tegument-delivered pp71 is cytoplasmic and Daxx is not degraded. The intrinsic defense is able to silence IE gene expression, and latency is established. While it is likely that BclAF1 and ATRX (depicted as transparent) also restrict viral gene expression during latency, this has not been demonstrated experimentally.

HCMV: Human CMV; HDAC: Histone deacetylase; IE: Immediate–early; MIEP: Major immediate–early promoter.

Newer data have refined this model. In addition to mediating its degradation, pp71 also induces the SUMOylation of Daxx [64]. The function of this modification remains to be determined, as SUMOylation has no discernible effect on Daxx degradation or IE gene expression. pp71 also disrupts the association of Daxx with the chromatin-remodeling protein ATRX. Whether pp71-mediated Daxx degradation or simple association is required for ATRX dispersal has not been determined. Knockdown of ATRX partially rescues the IE gene expression defect observed in the pp71-null virus [65]. Finally, pp71 has been shown to participate in the degradation of another HCMV restriction factor that suppresses IE gene expression: the BclAF1 protein [35]. While knockdown of BclAF1 promotes IE gene expression, it fails to rescue the growth defect of the pp71-null virus. Thus, it appears that proteins other than BclAF1 are more critical targets of pp71.

Latency

In the absence of pp71 function (null or DID mutation, proteasome inhibition or Daxx overexpression), IE genes are not expressed and productive replication is inhibited. This mirrors what happens when latent infections are established. During latency, only a small subset of viral genes are expressed [66], and thus a majority of viral genes, especially the IE genes, must be silenced. This would seem to indicate that tegument-delivered pp71 must somehow be inhibited from acting during latency.

This appears to be true, as Daxx is not degraded in the undifferentiated cells where quiescent [44] or true latent infections [43] are established. Quiescent infections in model cells such as NT2 teratoma cells and THP-1 monocytes are not characterized as truly latent because reactivation of these infections has not been efficiently achieved, although there are reports that challenge this paradigm [67,68]. True experimental latent infections can be established in CD34+ cells [69,70]. In these undifferentiated cells, Daxx is not degraded because tegument-delivered pp71 is sequestered in the cytoplasm and cannot bind to Daxx, which is a nuclear protein. Inactivation of the intrinsic defense through either chemical HDAC inhibition or Daxx knockdown permits IE gene expression during what would otherwise be quiescent [44] or latent [43] infections with the AD169 strain of HCMV, indicating that cytoplasmic sequestration of pp71 is functionally relevant during the establishment of latency (Figure 3).

Interestingly, clinical strain viruses appear to enact an additional, trans-dominant, HDAC-independent restriction to IE gene expression [43] that likely does not involve pp71. This additional, clinical strain-specific defense appears to explain why a previous report failed to demonstrate the rescue of IE gene expression in NT2 cells by knocking down Daxx, as the clinical strain Toledo was examined in that study [71]. Thus, preventing the lytic-phase localization and function of a tegument protein is one way HCMV achieves the silencing of IE gene expression when it establishes latency, but this is not the only way. The use by HCMV of an intrinsic cellular defense against lytic replication as one means to establish latency may represent an evolutionary dilemma for the host. Daxx alleles with reduced intrinsic defense function might impair the ability of HCMV to establish latency, but would likely leave the host more susceptible to lytic infections. Conversely, Daxx alleles mediating increased intrinsic resistance may more efficiently protect against rampant lytic infection, but increase the propensity for the virus to colonize the host by expanding the latent reservoir. Further complicating matters, Daxx is essential for murine embryogenesis [72]. Thus any selective pressure applied by HCMV or other viruses must be balanced by the need to maintain Daxx function during development. The lack of a suitable host solution to this conundrum likely plays some role in the success of HCMV as a human pathogen.

IE gene expression must also be initiated upon reactivation of latent infections to produce infectious progeny virions, a molecular event recently labeled ‘animation’ [73]. As pp71 initiates IE gene expression during lytic infection, it has been proposed as a potential mediator of animation as well. It is unlikely that enough tegument-delivered pp71 would remain in the cytoplasm to traffic to the nucleus and de-repress the IE genes upon differentiation of a latently infected cell. A more likely scenario would be that differentiation induces the transcription of the pp71 gene, creating de novo synthesized protein that is fully capable of entering the nucleus and animating the genome. As pp71 is classified as an early/late gene, this would require that the kinetics of pp71 expression differ substantially between lytic replication and reactivation. Such a scenario would mimic what has been observed during reactivation of HSV-1 latency, where expression of the tegument transactivator VP16 was detected prior to IE gene expression [74]. While pp71 expression prior to IE mRNA accumulation during reactivation was not detected [27], a definitive test of this model requires genetic experiments that have not yet been reported.

Proliferation

It was well established that HCMV infection modulated cell cycle progression [75] when pp71 was identified as a cell cycle stimulator through a candidate approach [76] using a newly developed flow cytometry assay [77,78]. The cell cycle consists of phases where the DNA is synthesized (S phase) or divided equally among daughter cells (mitosis; M phase). One gap phase (G1) follows M and precedes S phase, while another (G2) follows S and precedes M phase. A more extensive gap phase (G0) called ‘quiescence’ can occur during G1 in response to various stimuli, such as contact inhibition or serum withdrawal. pp71 was shown to have two independent effects on the cell cycle, stimulating quiescent cells out of G0 and into the S phase [34], and accelerating cycling cells through the G1 phase [76].

Sequence analysis of pp71 [34] identified a motif (LXCXD) (Figure 2) with similarity to the canonical Rb-binding motif (LXCXE) found in viral oncoproteins and cellular proteins such as HDACs. The Rb family of tumor suppressors consists of three members – Rb, p107 and p130 – which are expressed at different times and interact with different members of the E2F family of transcription factors [79]. E2Fs control the expression of many genes required for progression from G0/G1 into the S phase, and for DNA synthesis itself [80]. When bound to E2F, Rb and its associated HDAC repress transcription from E2F-responsive promoters, thus arresting cells in G0/G1 phase. In uninfected cells, CDKs phosphorylate Rb family members, disrupting their complexes with HDACs and E2Fs, thereby activating the expression of E2F-responsive genes and promoting cell cycle progression and DNA replication [80,81]. In infected cells, viral oncoproteins target the Rb family members, either inducing their proteasomal degradation or simply disrupting Rb–E2F complexes to promote cell cycle progression [82]. This presumably favors viral replication, especially for DNA viruses, by advancing quiescent cells into a cell cycle state where DNA replication would be more efficient. Surprisingly, there is little direct evidence for this widely accepted model.

pp71 proteins with mutated Rb-binding motifs fail to drive quiescent cells into the S phase [34], but still accelerate cells through the G1 phase [76], indicating that pp71 has at least two independent mechanisms to drive cell cycle progression. How pp71 accelerates the G1 phase is not understood, but how it stimulates quiescent cells to enter the S phase by targeting Rb has been deciphered. pp71 interacts with the growth-suppressive, hypophosphorylated forms of the Rb family members and induces their proteasomal degradation. A pp71 mutant with a disruption of the Rb-binding motif (LXGXD) is unable to induce Rb family member degradation [34]. Therefore, Rb protein degradation appears to be directly responsible for stimulating quiescent cells to enter the S phase, but not for accelerating cycling cells through G1 phase.

The physiologic relevance of pp71-mediated cell cycle stimulation is undetermined. During lytic replication, pp71-mediated Rb degradation is dispensable [56], presumably because UL97 also inactivates Rb through phosphorylation [57]. Perhaps in other cell types or other infection circumstances (e.g., reactivation from latency) pp71-mediated Rb degradation may be more important.

Finally, degrading Rb proteins is a pp71 activity shared with the E7 oncoproteins encoded by human papillomaviruses. However, unlike E7, pp71 fails to induce apoptosis, or to cooperate with other oncoproteins to transform cells [34]. It is unclear if this is due to a comparatively weaker effect on the Rb pathway by pp71 or because additional functions by one or the other protein is responsible for the phenotypic differences.

Degradation

Evidence that pp71 mediates the degradation of the proteins to which it binds includes a decrease in both their steady-state levels as determined by western blot, as well as their half lives as determined by pulse–chase analysis. Furthermore, proteasome inhibitors also stabilize binding partners in the presence of pp71, indicating that their degradation is proteasome-dependent [34,35,58,59]. The proteasome is a large, multisubunit complex responsible for the majority of protein degradation that occurs within cells. While most proteasome substrates must be covalently modified with a polyubiquitin chain prior to recognition and degradation, a few examples of proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation have been described [83]. All evidence points to a ubiquitin-independent mode for the proteasomal degradation induced by pp71 [58,84], although such a mechanism is difficult to prove [83], and many remain skeptical that proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation is either real or physiologically relevant.

The pp71 protein lacks easily discernable motifs (e.g., HECT domain or RING finger) found in the ubiquitin ligase proteins that target substrates for ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation, and polyubiquitinated intermediates of pp71 substrates have not been observed under conditions where their half lives are reduced by pp71. Furthermore, an overexpressed dominant-negative ubiquitin failed to inhibit pp71-mediated protein degradation [58]. While these experiments provide evidence for ubiquitin-independent degradation, they are all based on negative data. Perhaps the most compelling argument for the independence of pp71-mediated protein degradation from the need for polyubiquitination comes from the positive data generated in ts20 cells. These cells encode a temperature-sensitive E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme. When shifted to the restrictive temperature, E1 activity is inhibited and ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation ceases. Under such conditions, pp71-mediated degradation continues, implying that it is ubiquitin-independent [58,84]. However, even this result must be interpreted with caution, as cells contain at least one additional E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme [85] and because different substrates show different sensitivities to ubiquitin pool depletion through E1 inactivation [86].

The mechanism through which pp71-mediates the proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of its substrates remains unknown. Logical possibilities include direct delivery and/or unfolding of substrates to allow their access to proteasomes in the absence of polyubiquitination. Interestingly, pp71 has recently been shown to be necessary but not sufficient for the proteasomal degradation of BclAF1. For degradation of this substrate, pp71 cooperates with the viral UL35 tegument protein [35]. The requirement or dispensability of ubiquitin for pp71- and UL35-mediated BclAF1 degradation has not yet been examined. However, UL35 associates with components of cellular ubiquitin ligase complexes [87], implying that BclAF1 degradation induced by these two viral proteins may proceed through a ubiquitinated intermediate, and that pp71 may use multiple mechanisms to induce the degradation of its targeted substrates.

Finally, pp71 appears to preferentially target the variants of its substrates that migrate faster on standard SDS-PAGE gels [34,88]. For the Rb proteins, these clearly represent the hypophosphorylated forms of the proteins. For Daxx, it is presently unclear whether faster migrating bands represent different phosphoisoforms or splice variants [89] of the protein.

Immunoevasion

Establishment of latency, in which pp71 clearly plays a role, is perhaps the most effective immune evasion strategy employed by HCMV. However, HCMV also expresses many viral gene products designed to help a lytically infected cell avoid detection by the innate and adaptive immune systems [90]. Many of these rely on suppressing the function of the MHC class I set of proteins. All nucleated cells contain MHC class I molecules, which present peptides on the cell surface to CD8+ T lymphocytes. Presented peptides represent a sampling of the current protein production ongoing within the cell. Detection of a viral peptide by a CD8+ T lymphocyte typically results in lysis of the infected cell [91].

Multiple HCMV MHC class I evasion genes are located in the US region of the HCMV genome [92]. To determine whether other viral loci could alter the generation of immune responses, pp71 was ectopically expressed in semipermissive U373 cells. A modest but reproducible inhibition of cell surface expression of MHC class I molecules was observed upon pp71 expression. Moreover, knockdown of pp71 in cells infected with an HCMV lacking the immune evasion genes of the US region increased cell surface expression of MHC class I. The timing of this experiment (48 h postinfection) and the method of pp71 downregulation (RNAi) indicates that de novo-expressed (as opposed to tegument-delivered) protein was responsible for the observed effect. pp71 does not affect MHC class I gene expression or protein stability, but appears to delay the transport of these complexes through the endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi apparatus to the cell surface [93]. Whether pp71 accomplishes this by a direct or indirect mechanism is currently unclear. A direct mechanism would possibly appear late during infection as pp71 accumulates in assembly compartments [19,41], which colocalize with trans-Golgi markers [94,95]. However, pp71 is not known to associate with MHC class I molecules, and it is difficult to reconcile a direct mechanism with the subcellular localization of ectopically expressed pp71, which is nuclear, although cytoplasmic spillover can occur when the protein is overexpressed. Although intriguing, the relevance of this reported activity of pp71 during a wildtype infection (i.e., in the presence of the many other MHC evasion genes encoded in the US region) or in fully permissive cells has not been examined.

Finally, although pp71 neutralizes intrinsic and perhaps adaptive immune defenses, it appears to be a target of the innate immune system. Granzyme M, which is highly expressed by NK cells, was shown to cleave pp71 after leucine 439, inhibiting its ability to activate the MIEP in reporter assays [96]. More work is required to determine not only the role of this cleavage during the immune attack against HCMV-infected cells, but also why pp71 has not evolved to escape granzyme M-mediated cleavage. Possibilities include that this amino acid sequence is critical for pp71 function, and thus mutant alleles would adversely affect viral fitness or that granzyme M cleavage of pp71 does not exert significant selective pressure against HCMV. Granzymes generally kill infected cells by apoptosis [97]. However, granzyme B delivered by lytic granules released from CD8+ T cells cleaved the HSV-1 ICP4 protein and inhibited viral reactivation from neuronal latency without killing the infected cell [98]. Interestingly, neighboring fibroblasts lytically infected with HSV-1 appeared to die by apoptosis in these experiments, indicating that granzyme-mediated death may be cell type specific. If pp71 were required for animation of latent infections, perhaps granzyme-mediated cleavage may be a way to suppress reactivation in the presence of a specific and localized immune response while maintaining the viability of the latently infected cell.

Conclusion

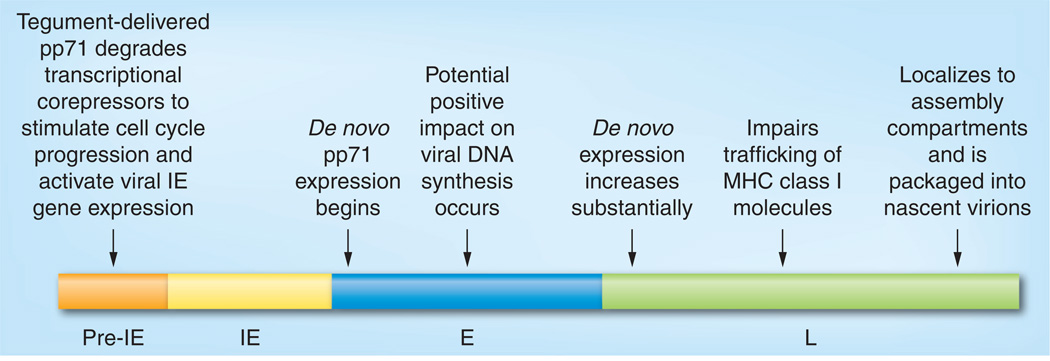

A timeline for pp71 function during viral infection can be compiled from the primary data reviewed above (Figure 4). After viral entry into differentiated cells where lytic infection will initiate, tegument-delivered pp71 travels to the nucleus, where it induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of cellular transcriptional regulators Daxx, BclAF1, Rb, p107 and p130. Daxx and Rb family member degradation is ubiquitin independent, and BclAF1 degradation requires co-operation with tegument-delivered UL35. Daxx and BclAF1 degradation promotes IE gene expression by inactivating the intrinsic defense imposed by these cellular restriction factors. Daxx degradation is critical for efficient viral replication. Rb family member degradation promotes cell cycle progression, but, probably due to redundant viral mechanisms for cell cycle stimulation, this degradation is dispensable for viral replication under the conditions tested. De novo pp71 is expressed with early/late kinetics. It initially localizes to the nucleus and may promote viral DNA replication through an unknown mechanism. Later during infection, pp71 is found in cytoplasmic assembly compartments, where it is packaged into virions and may help cells avoid immune detection by impairing the transport of MHC class I molecules to the cell surface.

Figure 4. Timeline of pp71 activities during lytic infection.

Known functions of pp71 are temporally placed within the time course of a human CMV infection.

E: Early; IE: Immediate–early; L: Late.

During the establishment of viral latency, tegument-delivered pp71 is found in the cytoplasm, preventing it from degrading Daxx. This allows the intrinsic defense to silence IE gene expression and promote latency. Involvement of pp71 during animation and reactivation remains to be examined, as does the potential roles for other activities of pp71 during latency.

Although the focus of this review is pp71, we would be remiss not to acknowledge the redundancy that exists for many of the biological process targeted by this important viral protein. Readers interested in more thorough examinations of individual activities modulated by pp71, as well as other HCMV factors, are directed to comprehensive reviews or recent primary research articles that cover intrinsic restriction of lytic gene expression [99,100], latency [3,101], cell cycle modulation [102] and immune evasion [103].

Future perspective

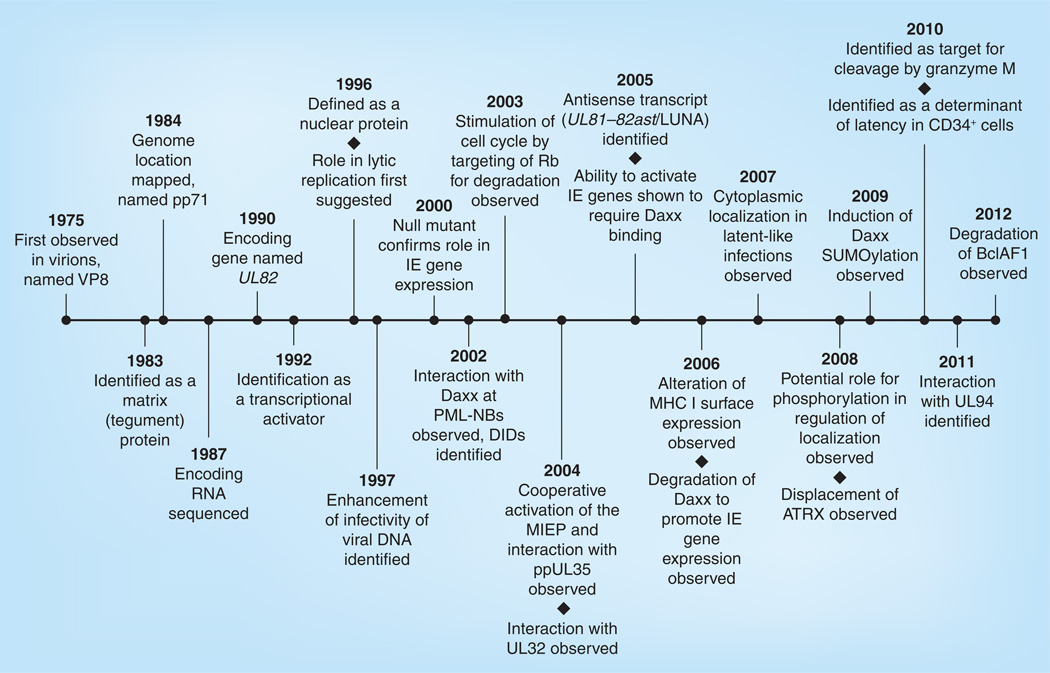

While nearly four decades of work (Figure 5) has illuminated the roles of pp71 during lytic infection and latency, substantial gaps in our knowledge still exist. Many of these are mechanistic in nature, including how pp71 is incorporated into the tegument, how the subcellular localization of the tegument-delivered protein is differentially controlled in differentiated or undifferentiated cells and how pp71, alone or in cooperation with UL35, promotes protein degradation. More fundamental questions still remain, including whether or not pp71 is required for the animation or reactivation of latent infections. Finally, many new pp71-interacting proteins have recently been identified. Determining which of these interactors may be potential substrates or modulators of pp71 could open new vistas to our understanding of the role of pp71 during HCMV infection.

Figure 5. Historical timeline of pp71.

Beginning with its identification in virions and ending with the recent identification of an additional cellular target of pp71-mediated degradation (BclAF1), this timeline highlights significant advancements during the history of pp71 research.

DID: Daxx interaction domain; IE: Immediate–early; MIEP: Major immediate–early promoter; PML-NB: Promyelocytic leukemia nuclear body; Rb: Retinoblastoma; VP: Virion protein.

Executive summary.

Nomenclature, expression & structure

pp71 is a 71-kDa phosphoprotein encoded by the 82nd gene in the unique long region of the viral genome.

pp71 is expressed with early/late kinetics as the second open reading frame of a 4-kb bicistronic transcript with UL83 (pp65) and as a 1.8-kb monocistronic transcript.

No structural information on pp71 exists.

Interactome & location

Ontology analysis of interactome predicts pp71 may impact gene expression, actin-based motility, RNA processing and ribosome biogenesis.

Subcellular localization of pp71 is controlled by method of delivery, cellular differentiation status, time of infection and phosphorylation.

Transactivation, genetics, de-repression & latency

pp71 inactivates intrinsic immune defense and stimulates immediate–early gene expression by degrading Daxx.

pp71 promotes latency by allowing Daxx intrinsic defense to silence immediate–early genes in undifferentiated cells due to cytoplasmic localization of tegument-delivered protein.

pp71 likely has additional roles, including facilitating viral DNA replication.

Proliferation, degradation & immunoevasion

pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression in part by degrading the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors.

pp71 mediates degradation of several of its substrates by a proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent mechanism.

pp71 impairs trafficking of MHC class I molecules to the cell surface.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank H VanDeusen for the illustrations, and members of the laboratory for helpful comments.

This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (AI074984) to RF Kalejta, who is a Vilas Associate and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪ ▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Boeckh M, Geballe AP. Cytomegalovirus: pathogen, paradigm, and puzzle. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121(5):1673–1680. doi: 10.1172/JCI45449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves M, Sinclair J. Aspects of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;325:297–313. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodrum F, Caviness K, Zagallo P. Human cytomegalovirus persistence. Cell. Microbiol. 2012;14(5):644–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mocarski E, Shenk T, Pass R. Cytomegaloviruses. In: Howley P, editor. Fields Virology. Lippincott, PA: USA; 2007. pp. 2701–2772. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendelson M, Monard S, Sissons P, Sinclair J. Detection of endogenous human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ bone marrow progenitors. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77(Pt 12):3099–3102. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn G, Jores R, Mocarski ES. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(7):3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sindre H, Tjoonnfjord GE, Rollag H, et al. Human cytomegalovirus suppression of and latency in early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;88(12):4526–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maciejewski JP, Bruening EE, Donahue RE, Mocarski ES, Young NS, St Jeor SC. Infection of hematopoietic progenitor cells by human cytomegalovirus. Blood. 1992;80(1):170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheshier SH, Morrison SJ, Liao X, Weissman IL. In vivo proliferation and cell cycle kinetics of long-term self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96(6):3120–3125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy E, Yu D, Grimwood J, et al. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(25):14976–14981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalejta RF. Tegument proteins of human cytomegalovirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008;72(2):249–265. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bresnahan WA, Shenk TE. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(26):14506–14511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14506. ▪ The genetic deletion of pp71 demonstrates its necessity for immediate–early gene expression and efficient replication.

- 13.Liu B, Stinski MF. Human cytomegalovirus contains a tegument protein that enhances transcription from promoters with upstream ATF and AP-1 cis-acting elements. J. Virol. 1992;66(7):4434–4444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4434-4444.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chee MS, Bankier AT, Beck S, et al. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1990;154:125–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarov I, Abady I. The morphogenesis of human cytomegalovirus. Isolation and polypeptide characterization of cytomegalovirions and dense bodies. Virology. 1975;66(2):464–473. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irmiere A, Gibson W. Isolation and characterization of a noninfectious virion-like particle released from cells infected with human strains of cytomegalovirus. Virology. 1983;130(1):118–133. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowak B, Sullivan C, Sarnow P, et al. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal immune sera directed against human cytomegalovirus virion proteins. Virology. 1984;132(2):325–338. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roby C, Gibson W. Characterization of phosphoproteins and protein kinase activity of virions, noninfectious enveloped particles, and dense bodies of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 1986;59(3):714–727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.714-727.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hensel GM, Meyer HH, Buchmann I, et al. Intracellular localization and expression of the human cytomegalovirus matrix phosphoprotein pp71 (ppUL82): evidence for its translocation into the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77(Pt 12):3087–3097. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak B, Gmeiner A, Sarnow P, Levine AJ, Fleckenstein B. Physical mapping of human cytomegalovirus genes: identification of DNA sequences coding for a virion phosphoprotein of 71 kDa and a viral 65-kDa polypeptide. Virology. 1984;134(1):91–102. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90275-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruger B, Klages S, Walla B, et al. Primary structure and transcription of the genes coding for the two virion phosphoproteins pp65 and pp71 of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 1987;61(2):446–453. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.2.446-453.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gatherer D, Seirafian S, Cunningham C, et al. High-resolution human cytomegalovirus transcriptome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(49):19755–19760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115861108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bego M, Maciejewski J, Khaiboullina S, Pari G, St Jeor S. Characterization of an antisense transcript spanning the UL81–82 locus of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 2005;79(17):11022–11034. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11022-11034.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy E, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus genome. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;325:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dal Monte P, Bessia C, Ripalti A, et al. Stably expressed antisense RNA to cytomegalovirus UL83 inhibits viral replication. J. Virol. 1996;70(4):2086–2094. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2086-2094.1996. ▪ First evidence that pp71 promotes human CMV infection.

- 26.Bego MG, Keyes LR, Maciejewski J, St Jeor SC. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein LUNA is expressed during HCMV infections in vivo. Arch. Virol. 2011;156(10):1847–1851. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves MB, Sinclair JH. Analysis of latent viral gene expression in natural and experimental latency models of human cytomegalovirus and its correlation with histone modifications at a latent promoter. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91(Pt 3):599–604. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umbach JL, Kramer MF, Jurak I, Karnowski HW, Coen DM, Cullen BR. MicroRNAs expressed by herpes simplex virus 1 during latent infection regulate viral mRNAs. Nature. 2008;454(7205):780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davison AJ, Stow ND. New genes from old: redeployment of dUTPase by herpesviruses. J. Virol. 2005;79(20):12880–12892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12880-12892.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Noh KM, Stadler SC, Allis CD. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(32):14075–14080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008850107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michaelson JS. The Daxx enigma. Apoptosis. 2000;5(3):217–220. doi: 10.1023/a:1009696227420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hofmann H, Sindre H, Stamminger T. Functional interaction between the pp71 protein of human cytomegalovirus and the PML-interacting protein human Daxx. J. Virol. 2002;76(11):5769–5783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5769-5783.2002. ▪▪ Detects the interaction of pp71 with Daxx.

- 33.Ishov AM, Vladimirova OV, Maul GG. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J. Virol. 2002;76(15):7705–7712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7705-7712.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalejta RF, Bechtel JT, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression by inducing the proteasome-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23(6):1885–1895. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.1885-1895.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SH, Kalejta RF, Kerry J, et al. BclAF1 restriction factor is neutralized by proteasomal degradation and microRNA repression during human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109(24):9575–9580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207496109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schierling K, Stamminger T, Mertens T, Winkler M. Human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins ppUL82 (pp71) and ppUL35 interact and cooperatively activate the major immediate–early enhancer. J. Virol. 2004;78(17):9512–9523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9512-9523.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips SL, Bresnahan WA. Identification of binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus virion proteins. J. Virol. 2010;85(1):440–447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01551-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.To A, Bai Y, Shen A, et al. Yeast two hybrid analyses reveal novel binary interactions between human cytomegalovirus-encoded virion proteins. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e17796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall KR, Rowley KV, Rinaldi A, et al. Activity and intracellular localization of the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83(Pt 7):1601–1612. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen W, Westgard E, Huang L, et al. Nuclear trafficking of the human cytomegalovirus pp71 (ppUL82) tegument protein. Virology. 2008;376(1):42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. Nuclear localization of tegument-delivered pp71 in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells is facilitated by one or more factors present in terminally differentiated fibroblasts. J. Virol. 2010;84(19):9853–9863. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00500-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saffert R, Penkert R, Kalejta R. Cellular and viral control over the initial events of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency in CD34+ cells. J. Virol. 2010;84(11):5594–5604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00348-10. ▪▪ Discovers the role of pp71 in the establishment of human CMV latency.

- 44.Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression is silenced by Daxx-mediated intrinsic immune defense in model latent infections established in vitro. J. Virol. 2007;81(17):9109–9120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00827-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.La Boissiere S, Hughes T, O’Hare P. HCF-dependent nuclear import of VP16. EMBO. J. 1999;18(2):480–489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spaete RR, Mocarski ES. Regulation of cytomegalovirus gene expression: alpha and beta promoters are trans activated by viral functions in permissive human fibroblasts. J. Virol. 1985;56(1):135–143. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.1.135-143.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stinski MF, Roehr TJ. Activation of the major immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus by cis-acting elements in the promoter-regulatory sequence and by virus-specific trans-acting components. J. Virol. 1985;55(2):431–441. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.2.431-441.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baldick CJ, Jr, Marchini A, Patterson CE, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 1997;71(6):4400–4408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4400-4408.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borst EM, Hahn G, Koszinowski UH, Messerle M. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J. Virol. 1999;73(10):8320–8329. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8320-8329.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paredes AM, Yu D. Human cytomegalovirus: bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) cloning and genetic manipulation. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2012;Chapter 14(Unit 14E.4) doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc14e04s24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Biegalke BJ. Human cytomegalovirus US3 gene expression is regulated by a complex network of positive and negative regulators. Virology. 1999;261(2):155–164. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chau NH, Vanson CD, Kerry JA. Transcriptional regulation of the human cytomegalovirus US11 early gene. J. Virol. 1999;73(2):863–870. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.863-870.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Homer EG, Rinaldi A, Nicholl MJ, Preston CM. Activation of herpesvirus gene expression by the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Virol. 1999;73(10):8512–8518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8512-8518.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Preston CM, Nicholl MJ. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 directs long-term gene expression from quiescent herpes simplex virus genomes. J. Virol. 2005;79(1):525–535. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.525-535.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmolke S, Kern HF, Drescher P, Jahn G, Plachter B. The dominant phosphoprotein pp65 (UL83) of human cytomegalovirus is dispensable for growth in cell culture. J. Virol. 1995;69(10):5959–5968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.5959-5968.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cantrell SR, Bresnahan WA. Interaction between the human cytomegalovirus UL82 gene product (pp71) and hDaxx regulates immediate–early gene expression and viral replication. J. Virol. 2005;79(12):7792–7802. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7792-7802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hume AJ, Finkel JS, Kamil JP, Coen DM, Culbertson MR, Kalejta RF. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science. 2008;320(5877):797–799. doi: 10.1126/science.1152095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kalejta RF, Shenk T. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of the Rb family of tumor suppressors by the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(6):3263–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538058100. ▪ Demonstrates that ubiquitin-independent degradation of retinoblastoma proteins by pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression.

- 59. Saffert RT, Kalejta RF. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic immune defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate–early gene expression. J. Virol. 2006;80(8):3863–3871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3863-3871.2006. ▪▪ Determines the mechanism through which pp71 activates viral immediate–early gene expression.

- 60.Cantrell SR, Bresnahan WA. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL82 gene product (pp71) relieves hDaxx-mediated repression of HCMV replication. J. Virol. 2006;80(12):6188–6191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02676-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Preston CM, Nicholl MJ. Role of the cellular protein hDaxx in human cytomegalovirus immediate–early gene expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87(Pt 5):1113–1121. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Woodhall DL, Groves IJ, Reeves MB, Wilkinson G, Sinclair JH. Human Daxx-mediated repression of human cytomegalovirus gene expression correlates with a repressive chromatin structure around the major immediate early promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281(49):37652–37660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604273200. ▪ Demonstrates that Daxx affects the chromatin structure of the viral genome.

- 63.Kalejta RF. Functions of human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins prior to immediate early gene expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;325:101–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hwang J, Kalejta RF. Human cytomegalovirus protein pp71 induces Daxx SUMOylation. J. Virol. 2009;83(13):6591–6598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02639-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lukashchuk V, McFarlane S, Everett RD, Preston CM. Human cytomegalovirus protein pp71 displaces the chromatin-associated factor ATRX from nuclear domain 10 at early stages of infection. J. Virol. 2008;82(24):12543–12554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01215-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slobedman B, Cao JZ, Avdic S, et al. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection and associated viral gene expression. Future Microbiol. 2010;5(6):883–900. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keyes LR, Bego MG, Soland M, St Jeor S. Cyclophilin A is required for efficient human cytomegalovirus DNA replication and reactivation. J. Gen. Virol. 2012;93(Pt 4):722–732. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.037309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu X, Yuan J, Wu AW, McGonagill PW, Galle CS, Meier JL. Phorbol ester-induced human cytomegalovirus major immediate–early (MIE) enhancer activation through PKC-delta, CREB, and NF-kappaB desilences MIE gene expression in quiescently infected human pluripotent NTera2 cells. J. Virol. 2010;84(17):8495–8508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00416-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goodrum F, Jordan CT, Terhune SS, High K, Shenk T. Differential outcomes of human cytomegalovirus infection in primitive hematopoietic cell subpopulations. Blood. 2004;104(3):687–695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reeves MB, Lehner PJ, Sissons JG, Sinclair JH. An in vitro model for the regulation of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation in dendritic cells by chromatin remodelling. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86(Pt 11):2949–2954. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Groves IJ, Sinclair JH. Knockdown of hDaxx in normally non-permissive undifferentiated cells does not permit human cytomegalovirus immediate–early gene expression. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88(Pt 11):2935–2940. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Michaelson JS, Bader D, Kuo F, Kozak C, Leder P. Loss of Daxx, a promiscuously interacting protein, results in extensive apoptosis in early mouse development. Genes Dev. 1999;13(15):1918–1923. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Penkert RR, Kalejta RF. Tegument protein control of latent herpesvirus establishment and animation. Herpesviridae. 2011;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/2042-4280-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson RL, Preston CM, Sawtell NM. De novo synthesis of VP16 coordinates the exit from HSV latency in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000352. e1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalejta RF, Shenk T. Manipulation of the cell cycle by human cytomegalovirus. Front. Biosci. 2002;7:d295–d306. doi: 10.2741/kalejta. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kalejta RF, Shenk T. The human cytomegalovirus UL82 gene product (pp71) accelerates progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 2003;77(6):3451–3459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3451-3459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kalejta RF, Brideau AD, Banfield BW, Beavis AJ. An integral membrane green fluorescent protein marker, Us9-GFP, is quantitatively retained in cells during propidium iodide-based cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;248(1):322–328. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalejta RF, Shenk T, Beavis AJ. Use of a membrane-localized green fluorescent protein allows simultaneous identification of transfected cells and cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1997;29(4):286–291. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19971201)29:4<286::aid-cyto4>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grana X, Garriga J, Mayol X. Role of the retinoblastoma protein family, pRB, p107 and p130 in the negative control of cell growth. Oncogene. 1998;17(25):3365–3383. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trimarchi JM, Lees JA. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3(1):11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adams PD. Regulation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein by cyclin/cdks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1471(3):M123–M133. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(01)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hume AJ, Kalejta RF. Regulation of the retinoblastoma proteins by the human herpesviruses. Cell Div. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hwang J, Winkler L, Kalejta RF. Ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation during oncogenic viral infections. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1816(2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hwang J, Kalejta RF. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of Daxx by the viral pp71 protein in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Virology. 2007;367(2):334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schulman BA, Harper JW. Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: the apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;10(5):319–331. doi: 10.1038/nrm2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salvat C, Acquaviva C, Scheffner M, Robbins I, Piechaczyk M, Jariel-Encontre I. Molecular characterization of the thermosensitive E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme cell mutant A31N-ts20. Requirements upon different levels of E1 for the ubiquitination/degradation of the various protein substrates in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267(12):3712–3722. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salsman J, Jagannathan M, Paladino P, et al. Proteomic profiling of the human cytomegalovirus UL35 gene products reveals a role for UL35 in the DNA repair response. J. Virol. 2012;86(2):806–820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05442-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tavalai N, Papior P, Rechter S, Stamminger T. Nuclear domain 10 components promyelocytic leukemia protein and hDaxx independently contribute to an intrinsic antiviral defense against human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 2008;82(1):126–137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01685-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wethkamp N, Hanenberg H, Funke S, et al. Daxx-beta and Daxx-gamma, two novel splice variants of the transcriptional co-repressor Daxx. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(22):19576–19588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Powers C, Defilippis V, Malouli D, Fruh K. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;325:333–359. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neefjes J, Jongsma ML, Paul P, Bakke O. Towards a systems understanding of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11(12):823–836. doi: 10.1038/nri3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lemmermann NA, Bohm V, Holtappels R, Reddehase MJ. In vivo impact of cytomegalovirus evasion of CD8 T-cell immunity: facts and thoughts based on murine models. Virus Res. 2011;157(2):161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Trgovcich J, Cebulla C, Zimmerman P, Sedmak DD. Human cytomegalovirus protein pp71 disrupts major histocompatibility complex class I cell surface expression. J. Virol. 2006;80(2):951–963. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.951-963.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Das S, Pellett PE. Spatial relationships between markers for secretory and endosomal machinery in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells versus those in uninfected cells. J. Virol. 2011;85(12):5864–5879. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00155-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanchez V, Greis KD, Sztul E, Britt WJ. Accumulation of virion tegument and envelope proteins in a stable cytoplasmic compartment during human cytomegalovirus replication: characterization of a potential site of virus assembly. J. Virol. 2000;74(2):975–986. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.975-986.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Van Domselaar R, Philippen LE, Quadir R, Wiertz EJ, Kummer JA, Bovenschen N. Noncytotoxic inhibition of cytomegalovirus replication through NK cell protease granzyme M-mediated cleavage of viral phosphoprotein 71. J. Immunol. 2010;185(12):7605–7613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chowdhury D, Lieberman J. Death by a thousand cuts: granzyme pathways of programmed cell death. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:389–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Knickelbein JE, Khanna KM, Yee MB, Baty CJ, Kinchington PR, Hendricks RL. Noncytotoxic lytic granule-mediated CD8+ T cell inhibition of HSV-1 reactivation from neuronal latency. Science. 2008;322(5899):268–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1164164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tavalai N, Stamminger T. Intrinsic cellular defense mechanisms targeting human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res. 2011;157(2):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zydek M, Uecker R, Tavalai N, Stamminger T, Hagemeier C, Wiebusch L. General blockade of human cytomegalovirus immediate–early mRNA expression in the S/G2 phase by a nuclear, Daxx- and PML-independent mechanism. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92(Pt 12):2757–2769. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sinclair J. Chromatin structure regulates human cytomegalovirus gene expression during latency, reactivation and lytic infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1799(3–4):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soroceanu L, Cobbs CS. Is HCMV a tumor promoter? Virus Res. 2011;157(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Noriega V, Redmann V, Gardner T, Tortorella D. Diverse immune evasion strategies by human cytomegalovirus. Immunol. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8304-8. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]