Abstract

Objectives

Patient reported outcomes (PRO) assessing multiple gastrointestinal symptoms are central to characterizing the therapeutic benefit of novel agents for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Common approaches that sum or average responses across different illness components must be unidimensional and have small unique variances to avoid aggregation bias and misinterpretation of clinical data. This study sought to evaluate the unidimensionality of the IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) and to explore person centered cluster analytic methods for characterizing multivariate-based patient profiles.

Methods

Ninety-eight Rome-diagnosed IBS patients completed the IBS-SSS and a single, global item of symptom severity (UCLA Symptom Severity Scale) at pretreatment baseline of an NIH funded clinical trial. A k-means cluster analyses were performed on participants symptom severity scores.

Results

The IBS-SSS was not unidimensional. Exploratory cluster analyses revealed four common symptom profiles across five items of the IBS-SSS. One cluster of patients (25%) had elevated scores on pain frequency and bowel dissatisfaction, with less elevated but still high scores on life interference and low pain severity ratings. A second cluster (19%) was characterized by intermediate scores on both pain dimensions, but more elevated scores on bowel dissatisfaction. A third cluster (18%) was elevated across all IBS-SSS sub-components. The fourth and most common cluster (37%) had relatively low scores on all dimensions except bowel dissatisfaction and life interference due to IBS symptoms.

Conclusions

PRO endpoints and research on IBS more generally relying on multicomponent assessments of symptom severity should take into account the multidimensional structure of symptoms to avoid aggregation bias and to optimize the sensitivity of detecting treatment effects.

Keywords: disease severity, questionnaire development, outcome research, health status indicators, rating scale, psychometric properties, global assessment

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic often times disabling gastrointestinal condition characterized by abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation, or both in an alternating manner). With a worldwide prevalence of 10-15% [1], IBS imposes a considerable burden both on the individual sufferer and society as a whole [2,3]. There is currently no satisfactory medical treatment for the full range of symptoms of IBS. Two of the past three drug therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of IBS have required regulatory intervention leading to drug withdrawal in one case and a severely restrictive risk management program in the other. These events, coupled with recent FDA restrictions on the primary study endpoint to be used in IBS pharmaceutical development, have reduced perceived commercial value of new drug development for IBS and limited options for one of the most common gastrointestinal disorder experienced by patients and seen by physicians in clinical practice [4].

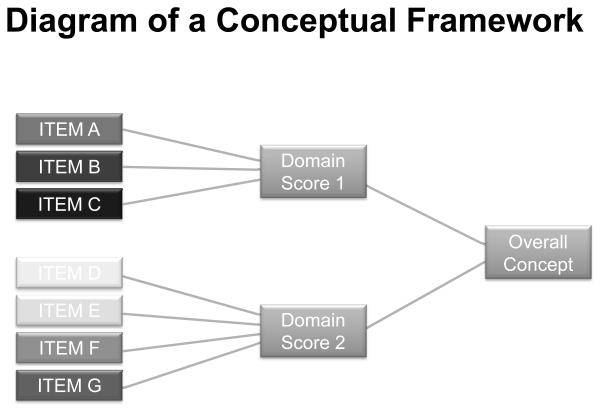

To meet the unmet need for safe and effective treatments for IBS, the U.S FDA’s Study Endpoint and Label Development (SEALD) group has issued a Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) Guidance document [5] that specifies a multistage procedure for evaluating novel agents using valid and reliable patient reported outcomes. The FDA regards IBS as one of the top five medical conditions for which a PRO is urgently needed. The process of developing a PRO begins with the delineation of a conceptual framework that clearly describes the relationship among what the PRO instrument is trying to measure [concept],the core signs or symptoms specific to the underlying disease or condition being assessed (domain), and the individual items representative of aspects of the domains; proceeds with both qualitative and quantitative research to define items reflecting those symptoms and establish their psychometric properties; and culminates in the production of a PRO measure that reflects therapeutic benefit from the patient’s perspective. Historically, attempts to develop patient reported endpoints have gravitated toward the construct of perceived severity of symptoms both as a metric for gauging illness status and the benefit of novel treatments. Representative of this approach is the IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS), a global measure of IBS symptoms that aggregate patient ratings of different, well defined domains of IBS into a single overall score. The IBS-SSS [6] has been recommended by the Rome Foundation [7] as the global endpoint for measuring IBS symptom severity in clinical trials. This scale asks individuals to rate four symptom dimensions, each measured on a 0 to 100 rating scale: a) the severity of abdominal pain; b) the severity of abdominal distention/tightness (bloating); (c) satisfaction with bowel habits; and d) life interference due to IBS symptoms. A final item asks the number of days out of previous 10 when the patient experiences abdominal pain with the answer multiplied by 10 to create a 0 to 100 metric for it.

Like other composite measures developed under the PRO initiative [8], the IBS-SSS generates a total aggregate by summing its items to derive an index of overall symptom severity. Combining items across multiple symptom domains for the purpose of generating a global score is a common practice in PRO development [9]. Theoretically this approach maps onto the requisite conceptual framework (see Fig. 1) the FDA recommends for constructing a PRO instrument whose overarching measurement focus (concept) is a product of multiple domains (e.g., signs and symptoms). Methodologically, however, aggregating scores from composite items potentiates at least two problems that can make scales misleading. The first problem is aggregation bias. The underlying mechanisms that impact one set of symptoms may differ from the underlying mechanisms that impact another set of symptoms. Aggregating across items obscures such dynamics. One is left with a total score whereby component scores may behave differently in response to a treatment or where the overall score masks a relationship between a component symptom and some other variable of clinical import. For example, a pharmacological treatment may impact defecatory symptoms but have limited, if any, effect on abdominal pain or discomfort. An overall score would then reflect a mixture of change on the item associated with bowel habits and random or systematic “noise” due to the pain items. The result is an index that can mask the true effects of the treatment or make it harder to detect those effects. By the same token, a novel agent may provide some pain relief but little, if any, benefit for defecatory symptoms. An aggregate index will capture both the genuine therapeutic change as well as “noise” due to the other components measured by the scale. Aggregation bias represents a serious threat to accurately characterizing patients’ experience of their disease and associated treatment which is the penultimate goal of the FDA’s PRO Guidance Document [10].

Adapted from US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/06d-0044-gdl0001.pdf. (2006).

A second problem is that variation in the total score, all else being equal, is dominated by whichever sub-component has the most variability across people. If patients exhibit considerable variation on the pain subscale but only modest variation on a subscale about defecatory symptoms such as stool frequency, then variations on the total score will primarily reflect variations in pain, not bowel symptoms. Such a dynamic would advantage agents with strong analgesic properties over those that are primarily designed to relieve defecatory symptoms when using the overall composite score to evaluate a therapeutic agent. This is particularly germane to the IBS-SSS because, three of its five items tap abdominal pain or discomfort (pain and bloating severity, number of pain days) and thus, likely contribute more variability to the total score. In effect, the IBS-SSS “triple weights” items assessing abdominal pain/discomfort over those assessing non pain aspects of IBS experience.

These issues are not necessarily problematic if individual items comprising a multi-item scale are highly correlated and unidimensional in nature. Unidimensional scales measure a single dimension or group of dimensions that cluster with one another. To the extent that a scale is unidimensional and items are highly correlated, then the behavior of one item parallels the behavior of other items. The extent to which composite measures of IBS (or for that matter other diseases) are unidimensional is thus an important and largely overlooked psychometric matter critical to the development of sound, meaningful, and sensitive PROs. To our knowledge, IBS endpoints have been developed without regard to documenting their unidimensional versus multidimensional proprieties. One purpose of the present study was to examine the unidimensional versus. multidimensional structure of the IBS-SSS.

To the extent that individual IBS symptoms are characterized by both non-trivial unique and common variance, it can be useful to identify symptom clusters that characterize significant numbers of patients with IBS. Different treatment regimens might then be implemented depending on the observed symptom patterns, with some therapeutic agents being more appropriate for some types of patients but less appropriate for other types. The present study applied cluster analytic methods to the core symptoms measured by the IBS-SSS scale with the objective of identifying distinct patient profiles that may require different approaches to symptom resolution. In contrast to traditional approaches that treat each symptom as a separate construct, person-centered cluster analysis uses an idiographic approach that represents the presentation of multiple symptoms as an organized whole [11].

Methods

Participants

Participants included 98 consecutively evaluated IBS patients recruited primarily through local media coverage and community advertising and referral by local physicians to a tertiary care center at an academic medical center. To qualify, participants must have met Rome II IBS diagnostic criteria [12] without organic gastrointestinal disease (e.g., IBD, colon cancer, etc) as determined by a board-certified study gastroenterologist. Because this study was conducted as part of a clinical trial for more severely affected patients with IBS, participants must have also reported IBS symptoms of at least moderate intensity (i.e., symptom occurring at least twice weekly for 6 months and causing life interference). Institutional review board approval and written, signed consent were obtained before the study began. This study was completed in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure

After a brief telephone interview to determine whether participants were likely to meet basic inclusion criteria, participants were scheduled for a medical examination to confirm IBS diagnosis [12,13] and psychometric testing, which for the purposes of this study included the following test battery. Detailed information about study procedure can be found elsewhere [14]

Measures

The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) [6] is a 5-item instrument used to measure severity of abdominal pain, frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distension, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference with quality of life on a 100-point scale. For four of the items, the scales are represented as continuous lines with endpoints 0% and 100%, with different descriptors at the endpoints and adverb qualifiers (e.g., “not very,” “quite”) strategically placed along the line. Respondents mark a point on the line reflecting the extremity of their judgment between the two endpoints and the proportional distance from zero is the score assigned for that scale (hence scores range from 0 to 100). The endpoints for the severity items are “no pain” and “very severe,” for satisfaction, the endpoints are “not at all satisfied” and “very satisfied,” and for interference they are “not at all interferes” to “completely interferes.” A final item asks the number of days out of 10 the patient experiences abdominal pain and the answer is multiplied by 10 to create a 0 to 100 metric. The items were summed and thus the total score could range from 0 to 500. The IBS-SSS was used as an endpoint of the clinical study from which secondary analyses were derived for this study.

We also obtained a single item, global measure of symptom severity using the UCLA Global Severity of Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scale (UCLA-SSS). The UCLA SSS [15] is a 21-point rating scale where participants rate the overall severity of their symptoms (where the specific symptoms are unspecified) on a 0 (no symptoms) to 20 (most intense symptoms imaginable) point scale.

Data Analytic Plan

To place variables on a common metric and to ease interpretation of some analyses, all measures were re-scaled to a 0 to 10 metric. This was accomplished by subtracting the lowest possible score attainable for each variable from an individual’s observed score and then dividing this by the highest possible score on that variable. This result was then multiplied by 10. Thus, scores for every variable range from 0 to 10 with a midpoint of 5. This strategy represents a simple linear transformation that preserves differential variability, differential central tendencies, and distributional forms for the variables, all while establishing a common 0 to 10 metric. We first tested if the five component measures of the IBS-SSS scale behaved in accord with a single factor model (i.e., unidimensionality) using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) based on maximum likelihood methods. Once unidimensionality was rejected, we used exploratory factor analysis to gain insights into the underlying dimensional structure of the scale, based on principal components extraction with an oblimin rotation. The oblimin rotation permits the underlying factors to be correlated, which seemed more theoretically compelling than a varimax rotation. Finally, as described later, cluster analysis of the measures was applied to the data using K-means clustering algorithms which are described below. This method of analysis identifies clusters of individuals who show similar profiles across the component symptoms but who have distinct profile relative to individuals in other clusters. The goal is to classify individuals into categories, with each category containing individuals who are similar to each other and different from individuals in other categories. Such an approach is useful in IBS research where there is known heterogeneity in the complexion of symptoms that characterize patients with a common syndrome. The K-means algorithm specifies a fixed number of clusters, k, and assigns cases to clusters so that the means for all variables are as different from each other as possible for the different clusters. The value of k is determined through successive solutions that increment the value of k by one, with the chosen solution being one that yields theoretically meaningful cluster profiles that meaningfully increment estimates of explained variance relative to solutions with smaller k, and whose cluster sizes are not trivial. Although it would have been preferable to use more modern methods of classification analysis, such as Latent Profile Analysis, the sample size was judged to be too small for such methods. As such, the results reported here should be viewed as illustrative and tentative.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

There were minimal missing data, amounting to no more than a few cases on most variables and representing less than 2% of the cases. Missing values were imputed using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method based on Schafer [16] . Non-normality of the variables was evaluated by computing values of skewness and kurtosis. These values as well as the means and standard deviations of the variables are presented in Table 1. We evaluated the data for multivariate outliers using a leverage statistic. An individual was identified as an outlier if s/he had a leverage score four times larger than the mean leverage index. No outliers were identified.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | Std. Dev | Skewness | Kurtosis | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | - | - | - | - | 88% |

| Married | - | - | - | - | 29% |

| Employed full time | - | - | - | - | 46% |

| Graduating college | - | - | - | - | 52% |

| Age, y | 46.7 | 16.9 | .03 | −.99 | |

| Months with IBS | 197.8 | 184.0 | 1.05 | .06 | |

| UCLA-SSS | 5.49 | 2.03 | −.36 | −.35 | |

| IBS-SSS | 5.97 | 1.54 | −.11 | −.29 | |

| Bowel subtypes | |||||

| IBS-Diarrhea | - | - | - | - | 41% |

| IBS-Constipation | - | - | - | - | 39% |

| IBS-Mixed | - | - | - | - | 18% |

| Missing | - | - | - | - | 2% |

Note: Untransformed mean for UCLA-SS is 11.52 and for IBS-SSS it is 298.5.

The Unidimensionality of the IBS-SSS Measure

To determine if the five component items of the IBS-SSS are unidimensional in structure, a single factor CFA model was fit to the 5 × 5 covariance matrix for the items. The single factor model yielded a poor fit to the data (chi square with 5 degrees of freedom = 19.99, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.80, RMSEA = 0.18, p value for close fit < 0.01), suggesting a multidimensional structure. An exploratory factor analysis on the component measures was performed using principal components extraction and an oblimin rotation. A two factor solution was suggested by the analysis, with the two pain and bloating items loading on one abdominal pain/discomfort factor and the life interference and satisfaction with bowel items loading on the second symptom burden factor. Columns 2 through 6 of Table 2 present the 5×5 correlation matrix between the component measures as well as the standardized factor loadings and standardized unique variances for the two factor solution. Even though a two factor model reasonably accounts for the correlations between the measures, several of the individual measures have considerable unique variance associated with them, independent of the two common factors, ranging from about 25% to 50%. These data are presented in Table 2. The presence of substantial unique variance was even true of pain items, one of which taps the number (frequency) of pain days and the other tapping pain intensity. This suggests that even forming two “total scores,” one for each of the factors observed in the factor analysis, may obscure important dynamics for some of the component measures in their own right when mapping out the mechanisms underlying IBS symptoms. The estimated correlation between the factors was 0.20.

Table 2.

Correlations between IBS-SSS Component Items, the Total IBS-SSS Score, and Results of a Factor Analysis on the Items

| Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain- Severity |

Pain- Freq |

Bloat | Bowel | Interfere | F1 Loading |

F2 Loading |

Unique Variance |

|

| Total | .76* | .76* | .66* | .42* | .57* | - | - | - |

| Pain-Sev | 1.00 | .87 | .17 | .24 | ||||

| Pain-Frq | .45* | 1.00 | .65 | .45 | .48 | |||

| Bloating | .53* | .29* | 1.00 | .80 | .02 | .34 | ||

| Bowel Dis | .00 | .23* | .02 | 1.00 | .00 | .85 | .25 | |

| Interfer | .30* | .25* | .14 | .35* | 1.00 | .33 | .75 | .41 |

Notes: signifies a statistically significant correlation, p < 0.05; “Total” refers to the total score on the IBS-SSS scale; Factor loadings are standardized; Unique variances are standardized and reflect proportion of variance in a measure unaccounted for by the two factors: F1= Factor 1, F2 = Factor 2.

Exploratory Cluster Analysis of Items of the IBS-SSS

Given the failure of unidimensionality for the IBS-SSS and the pattern of correlations in Table 3, we conducted exploratory cluster analyses on the items of the IBS-SS using a K-means clustering algorithm. A four group solution was settled upon. The cluster sizes and profile means on the 5 items are presented in Table 3. All means are on a 0 to 10 metric, with 5 representing the scale midpoint.

Table 3.

Profile Means for K Means Cluster Analysis

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain-severity | 3.97 | 5.01 | 7.28 | 1.75 |

| Pain-frequency | 9.22a | 4.29 | 8.72a | 3.27 |

| Bloating | 3.85a | 6.11 | 7.53 | 2.97a |

| Bowel dissatisfaction | 8.97a | 7.16 | 8.94a | 8.28a |

| Life interference | 7.11a | 6.61b | 8.11a | 6.34b |

| Percent of cases | 25.5% | 19.4% | 18.4% | 36.7% |

| UCLA severity mean | 5.56a | 5.86a | 7.19 | 4.41 |

Notes: Within a row, cluster means are statistically significantly different at p < 0.05 if they do not share a common superscript; The UCLA severity scale was not a formal part of the cluster analysis. The mean values as a function of cluster are reported here for their interest value.

The first cluster of patients, representing about 25% of the cases, is characterized by elevated scores on pain frequency and bowel dissatisfaction, with somewhat less elevated but still high mean scores on life interference. However, the pain severity ratings tend to be low. The second cluster of patients, representing about 19% of the cases, is characterized by intermediate scores on the pain dimensions, with somewhat more elevated scores on bowel dissatisfaction. The third cluster of patients, representing about 18% of the cases, is elevated on all sub-components. Finally, the fourth cluster of patients, representing about 37% of the cases, has relatively low scores on all dimensions except bowel dissatisfaction, with a somewhat elevated mean for life interference due to IBS symptoms.

It is interesting to compare the four clusters on the overall global ratings of symptom severity on the independently assessed UCLA severity scale. Table 3 reveals, not surprisingly, that the mean global characterization of IBS symptom severity is highest for cluster 3 patients who scored high on all IBS-SSS subscales and somewhat elevated for cluster 1 and 2 patients.

Variance Contributions of Individual Items to the Total Score

The first row of Table 2 presents the correlations between the individual items of the IBS-SSS and the total IBS-SSS score. The correlations are strongest for the two pain items. The squared semi-partial correlation between the two pain items and the total score was 0.19 (holding constant the other items), suggesting that the pain items uniquely account for 19% of the variation in the total scores. The squared semi-partial correlation for bloating and the total score was 0.07, suggesting it uniquely accounts for 7% of the variation in IBS-SSS. For bowel dissatisfaction, the squared semi-partial correlation was 0.05, suggesting it uniquely accounts for 5% of the variation in the IBS-SSS total score, and for life interference, it was 0.04, suggesting it uniquely accounts for 4% of the variation in the total IBS-SSS score. Using the logic of communality analysis [17], 66% of the variation in the total score was due to variance common to two or more of the items, whereas 34% of the variation was unique to individual items independent of this common variance.

Discussion

The present study explored psychometric properties of a multi-domain PRO scale, the commonly used IBS-SSS. Several interesting results emerged.

First, we found that the multi-item IBS-SSS was not unidimensional in character, but rather multidimensional. The individual items were only moderately correlated with one another and patterned themselves in accord with a two factor/latent variable model underlying their associational structure rather than one. Although two latent variables can reasonably account for the correlations between the component items, each component also was found to have non-trivial amounts of unique variance, suggesting that each component probably should be treated separately to avoid aggregation bias. For example, even though pain frequency and pain intensity were correlated 0.45, the estimated proportion of unique variance in each measure that could not be accounted for by the common factors was 0.24 and 0.48, respectively. This item-specific unique variance is large enough that these two facets of pain could respond differentially to treatment or show differential associations to variables designed to illuminate the mechanisms underlying IBS symptomology. At these early stages of theory development in IBS research, it probably is judicious to keep such measures separate and to empirically document their common versus unique response to different treatment protocols rather than to collapse them into an aggregate index that obscures possible differential dynamics among component symptoms. One option is to adopt co-primary endpoints reflecting the core symptoms that define IBS (i.e. abdominal pain and bowel symptoms). Beyond issues of sample size, trial costs, and drug development timelines, this approach presumes that two symptoms accurate capture the patient’s experience (i.e. equally intense, bothersome, distressing, impactful). To be sure, some patients experience bowel symptoms and pain as equally problematic. But for some patients, abdominal pain or discomfort is the most clinically significant IBS symptom; while for other he illness is defined by their bowel symptoms [18,19]. The assumption that the clinical significance of IBS symptoms is necessarily uniform across all patients runs the risk of imposing through endpoint selection a value judgment on patients’ symptom experience. To us, this would undermine a core principle of the PRO movement namely incorporating into therapy development the patient’s perspective on the impact of a disease and its treatment on his/her functioning and well-being. An alternative approach based on the recently released FDA guidance [20] is to calibrate the selection of endpoints to the target symptom and its putative mechanism of action, e.g.. drugs that target abdominal pain would use a single endpoint of pain intensity.

Of course, if one’s goal is merely to document a consistently low score across all symptoms without concern for the different mechanisms that can produce moderate to high scores, then aggregating across the diverse items can be justified. However, aggregating items that are multidimensional in structure carries a realistic risk of introducing a degree of noise that makes it difficult to understand the patients experience and detect treatment effects. This is particularly problematic for agents that differentially impact different aspects of a given disease “where the intention is not necessarily to cure but to ameliorate symptoms, facilitate functioning, or improve quality of life” [8]. For these reasons, we believe that such practices are not conducive to building an informative and useful knowledge base surrounding IBS [21]. Nor will it lend itself to characterizing precisely the therapeutic benefit of novel agents for specific symptoms. In our opinion, it is preferable to distinguish between the different components defining IBS symptom severity and to model these components separately or multivariately, such as in a person-centered approach.

To this end, we conducted an exploratory cluster analysis of the five symptom items of the IBS-SSS to identify meaningful, distinct patient profiles on the basis of their IBS-SSS responses. We found evidence for four discrete patient subtypes or profiles. One cluster of patients (25%) was characterized by elevated scores on pain frequency and bowel dissatisfaction, with somewhat less elevated but still high mean scores on life interference. The pain severity ratings, however, tended to be relatively low. Although these patients do not report severe pain, what pain they experience is persistent and a source of moderate life interference. A second cluster of patients (19%) was characterized by intermediate scores on the pain dimensions, but with more elevated scores on bowel dissatisfaction. These patients seem to endure IBS without experiencing the levels of pain of other groups of patients, but their symptoms take a toll on their well-being. A third cluster of patients (18%) was elevated on all sub-components of the IBS-SSS. Finally, the fourth and most common cluster of patients (37%) had relatively low scores on all dimensions except dissatisfaction with bowels and, to a lesser extent, IBS interfering with one’s life. Interestingly, the mean global characterization of IBS symptom severity was highest for cluster 3 patients, lowest for cluster 4 patients, and somewhat elevated for cluster 1 and 2 patients. This analysis, of course, was based on a relatively small sample and a restricted population from a single investigative team, so it must be interpreted judiciously. However, future research might benefit from adapting a person-centered approach to data analysis to characterize common combinations of IBS symptoms. Both the factor analyses and the cluster analyses underscore the utility of differentiating rather than aggregating symptom dimensions.

Clinically, these data have important implications. Classifying patients into subgroups on the basis of features they share may expand our understanding of a disorder marked by dramatic heterogeneity. To date, the most sophisticated mechanism for making sense of the clinical diversity of IBS are the Rome criteria [22]. The goals of Rome criteria, like any classification system, is identifying common features within groups of individuals (within group homogeneity) and identifying differences with groups of individuals (between group heterogeneity). The nomothetic focus of any diagnostic system means that it is concerned with grouping of individuals not heterogeneity within these groups (within group heterogeneity). As such, it is often assumed that once subjects have been assigned a diagnostic label (e.g., met Rome criteria for IBS) they are sufficiently similar to be randomly assigned to treatment arms in order to determine the efficacy of a novel agent. The tacit assumption that all patients with a given disorder are one homogeneous group – what is referred to as the patient uniformity myth [23] -- is intrinsic to most clinical research that features randomized clinical trials. But just because patients enrolled into a clinical trial satisfy diagnostic criteria does not necessarily mean they suffer from the same set of problems any more than family members who share the same surname have identical attributes. Not all patients diagnosed with IBS are the same. The severity and complexion of their symptoms, underlying pathophysiology, and treatment motivations (e.g., pain reduction, bowel symptom relief) differ often dramatically between patients. Assigning a diagnostic label links individuals of a heterogeneous population on the basis of shared clinical attributes, but it does not “homogenize” pathogenic processes, diverse symptom dimensions or patients’ treatment goals. We are not confident that global endpoints (e.g. adequate relief, IBS-SSS, composite symptom severity scores) are psychometrically sound enough to correct for the within group heterogeneity that characterizes IBS patients of so many different stripes. Indeed, there are some reasons to believe that they may actually introduce error variance that makes it more difficult to detect the beneficial effect of therapy [24]. Disregarding individual differences that make up the symptom topography of patients who share a diagnostic label may very well explain why so many studies testing the therapeutic benefit of novel agents yield disappointing results. Peripherally acting therapies for IBS have demonstrated partial efficacy at best with numbers needed to treat (NNT) in the double digits [25]. CNS pharmacotherapies that have proven efficacious for non-GI pain disorders [26] [27] have a disappointing track record with IBS in spite of a growing body of evidence highlighting the abnormal pain processing pathways in IBS [28].

Our data raise the question of whether meaningful conclusions regarding the therapeutic benefit of a given therapy can be confidently drawn until patient heterogeneity is recognized and factored into the design and interpretation of RCTs. If not, then researchers would be wise to move beyond the “horserace “ questions of does treatment X work better than Y for patients with the a shared diagnosis and confront the question of what treatments produce what changes for which kind of symptoms [21]. Establishing subtypes of IBS may help develop more targeted, effective interventions that are calibrated to the symptoms for which patients seek relief not the diagnosis they have been assigned. For an illness as heterogeneous as IBS, a claim based on diagnosis confers little information about the specific symptoms for which a treatment is beneficial. A more tailored approach may optimize treatment benefits, minimize harms, and conserve use of limited health resources. The process of subgrouping patients may yield indirect benefits to physicians and their patients. Because unrecognized heterogeneity among patients can undermine the power of a randomized trial to detect a truly beneficial treatment [29,30], efforts to systematically minimize heterogeneity may help accelerate the development of novel agents and index more accurately their genuine treatment effects that differences among study participants may obscure. This may in the long term improve the quality of care and reduce the disease burden of IBS

The results of this study are by no means the last or first word on subtyping IBS patients. Previous, efforts to delineate IBS subgroups have focused on patterns of symptoms (e.g., predominant bowel type), their severity, visceral hyperalgesia, intestinal transit, psychological distress, and illness behaviors [31-38]. We chose to use the IBS-SSS as a basis for subtyping because the Rome Foundation recommends it as an endpoint in clinical trials [7]. That said, we understand that its scope is limited to subjective complaints. Other factors that make up the multifactorial puzzle of IBS include gut-related dysfunctions (motility, secretion, immune function, permeability) as well as brain-related alterations, including increased stress reactivity,[39], impaired coping styles[40], selective attention to threat and symptom-related fears[41] . Further research that integrates the biobehavioral variables and instruments (patient reported outcomes, biological assessments) that define a subgroup scheme with the greatest clinical and research utility is urgently needed.

The results of the present research, of course, must be interpreted in light of limitations. The sample is relatively small and representative of only a single clinic in an academic medical center located in the Northeast. Because the measures of all constructs were based on self-report data, they are subject to some bias and measurement error, which can bias parameter estimates. K-means classification algorithms are less than optimal but we could not use more advanced latent class analyses because of sample size restrictions. Because this is a cross sectional study, data were collected at a single point in time. In light of research showing that subtyping of bowel habits among a significant proportion of IBS patients changes over time [42], it will be important to determine the temporal stability of subtyping derived from the IBS-SSS using longitudinal research designs. Despite such limitations, the results of the research are interesting and set the stage for more refined empirical work on the important issues identified. The research suggests the need to distinguish between different GI symptoms defining IBS severity, without obscuring matters through aggregation into total scores unless unidimensionality can be first demonstrated. This is an empirical question that demands more than leaps of faith to heed the FDAs call for quality PROs. Even if there is evidence of unidimensionality, if the one or more of the individual items has large amounts of unique variance, then, averaging items relegates the unique features of a single symptom to error variance and diverts attention from what might be clinically meaningful facets of patient experience of IBS. These are weighty psychometric issues. In the end, attention to these important maters will go a long way in creating an empirically sound, meaningful and clinically useful PRO that is sensitive to the treatment effects of agents for IBS and other disease states whose symptoms lack a reliable biomarker and are best understood from the patient perspective.

Acknowledgments

Source of financial support: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the IBS PRO Working Group of which two of the authors (JML, CB) are members.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy RL, Von Korff M, Whitehead WE, et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome patients in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3122–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Zack MM, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: can less be more? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:312–20. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204897.25745.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer EA. Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1692–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for Industry Irritable Bowel Syndrome — Clinical Evaluation of Products for Treatment. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irvine EJ, Whitehead WE, Chey WD, et al. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1538–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnanasakthy A, Mordin M, Clark M, et al. A review of patient-reported outcome labels in the United States: 2006 to 2010. Value Health. 2012;15:437–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revicki DA, Camilleri M, Kuo B, et al. Development and content validity of a gastroparesis cardinal symptom index daily diary. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:670–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration [Accessed March 10, 2012];Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 2009 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UC M193282.pdf.

- 11.Magnusson D, Pervin L, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Guilford; New York: 1990. Personality development from an interactional perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment: A multinational consensus. Second ed Degnon Associates; McLean, VA: 2000. Rome II. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, et al. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, et al. Predictors of patient-assessed illness severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2536–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman & Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seibold D, McPhee R. Commonality analysis: A Method for decomposing explainedvariance in multiple regression analyses. Human Communications Research. 1979;5:355–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Northcutt AR, Harding JP, Kong S, et al. Urgency as an endpoint in IBS. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(pt2):A1036. [Google Scholar]

- 19.International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders . IBS in the real world. IFFGD; Milwaukee, WI: 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Drug Administration [Accessed March 10, 2012];Guidance for Industry Irritable Bowel Syndrome — Clinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment. 2012 May; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm or http://www.regulations.gov.

- 21.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, et al. How does cognitive behavior therapy for irritable bowel syndrome work? A mediational analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:433–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. The functional gastrointestinal disorders: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment: A multinational consensus. 2 ed Degnon Associates; McLean, VA: 2006. Rome III. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiesler DJ. Some myths of psychotherapy research and the search for a paradigm. Psychological Bulletin. 1966;65:110–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lackner J, Jaccard J, Baum C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for irritable bowel syndrome are associated with patients’ severity ratings of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological factors. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah E, Kim S, Chong K, et al. Evaluation of harm in the pharmacotherapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Med. 2012;125:381–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camilleri M. Pharmacology of the new treatments for lower gastrointestinal motility disorders and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:44–59. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19–31. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00669-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer EA, Tillisch K. The brain-gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:381–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012309-103958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betensky RA, Louis DN, Cairncross JG. Influence of unrecognized molecular heterogeneity on randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2495–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Betensky RA, Louis DN, et al. The use of frailty hazard models for unrecognized heterogeneity that interacts with treatment: considerations of efficiency and power. Biometrics. 2002;58:232–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cann PA, Read NW, Brown C, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: relationship of disorders in the transit of a single solid meal to symptom patterns. Gut. 1983;24:405–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.5.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellow JE, Gill RC, Wingate DL. Prolonged ambulant recordings of small bowel motility demonstrate abnormalities in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(5 Pt 1):1208–18. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Munakata J, et al. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:40–52. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G. Division of the irritable bowel syndrome into subgroups on the basis of daily recorded symptoms in two outpatients samples. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:993–1000. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snape WJ, Jr., Carlson GM, Cohen S. Colonic myoelectric activity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:326–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehead WE. Patient subgroups in irritable bowel syndrome that can be defined by symptom evaluation and physical examination. Am J Med. 1999;107:33S–40S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS. Is rectal pain sensitivity a biological marker for irritable bowel syndrome: psychological influences on pain perception. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1263–71. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor I, Darby C, Hammond P, et al. Is there a myoelectrical abnormality in the irritable colon syndrome? Gut. 1978;19:391–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.5.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12:453–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lackner J, Jaccard J, Baum C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for irritable bowel syndrome are associated with patients’ severity ratings of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological factors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:957–964. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, et al. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: Further validation of the Visceral Sensitivity Index. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:89–98. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e2f24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Hu Y, et al. A prospective assessment of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome in women: defining an alternator. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:580–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]