Abstract

Purpose

Aberrant vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling have been shown to play a role in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) pathogenesis and are associated with decreased survival. We evaluated the clinical activity and tolerability of sunitinib malate (SU11248), an oral, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the activity of receptors for VEGF and PDGF, as well as related tyrosine kinases in patients with previously treated, advanced NSCLC.

Patients and Methods

Patients with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC for whom platinum-based chemotherapy had failed received 50 mg/d of sunitinib for 4 weeks followed by 2 weeks of no treatment in 6-week treatment cycles. The primary end point was objective response rate (ORR); secondary end points included progression-free survival, overall survival, and safety.

Results

Of the 63 patients treated with sunitinib, seven patients had confirmed partial responses, yielding an ORR of 11.1% (95% CI, 4.6% to 21.6%). An additional 18 patients (28.6%) experienced stable disease of at least 8 weeks in duration. Median progression-free survival was 12.0 weeks (95% CI, 10.0 to 16.1 weeks), and median overall survival was 23.4 weeks (95% CI, 17.0 to 28.3 weeks). Therapy was generally well tolerated.

Conclusion

Sunitinib has promising single-agent activity in patients with recurrent NSCLC, with an ORR similar to that of currently approved agents and an acceptable safety profile. Further evaluation in combination with other targeted agents and chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for 1.18 million deaths per year.1 New agents using novel treatment approaches are needed to improve survival outcomes. Recent nonclinical and clinical studies have identified critical biologic pathways in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which are growth factors that play an important role in tumor growth. Elevated expression of VEGF is a strong prognostic indicator in NSCLC and is associated with early postoperative relapse and decreased survival,2 and increased expression of PDGF has also been associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC.3,4 Furthermore, these pathways may cooperate in neoangiogenesis. In nonclinical studies using human lung squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma cell lines, as well as surgically resected fresh human NSCLC samples, PDGF-AA (which binds to the PDGF receptor [PDGFR]-α) was shown to be an essential regulator of VEGF expression.5,6 Thus PDGF as well as VEGF pathways are rational targets for antiangiogenic therapy in NSCLC and rational targets for anticancer therapy. Therefore, multitargeted inhibition of angiogenic pathways may be a more effective therapy for NSCLC than single-pathway inhibition.

Clinical studies with bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the VEGF-A ligand, have shown that targeting angiogenesis increases the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic regimens in NSCLC.7–9 In a phase II/III study evaluating carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced disease who had not received prior treatment,8 the addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel treatment significantly improved response rate (35% v 15%; P < .001), median progression-free survival (6.2 v 4.5 months; P<.001), and median overall survival (12.3 v 10.3 months; P = .003).

Sunitinib malate is an oral, selective multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic and antitumor activities. It inhibits VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-1, -2, and -3 and PDGFR-α and -β activity, as well as the activity of several related tyrosine kinases10–13 (Pfizer Inc; data on file). In preclinical studies, sunitinib effectively inhibited the growth of established human NSCLC xenografts,11 and antitumor activity has also been observed in patients with NSCLC in a phase I study.14 Phase III studies with sunitinib in other types of cancers have shown clinical efficacy with acceptable tolerability at a dose of 50 mg/d administered for 4 weeks, followed by 2 weeks of no treatment, in repeated 6-week cycles.15–17 This treatment regimen was used in the current phase II, open-label, multicenter study to evaluate the clinical activity and tolerability of sunitinib in patients with advanced NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Male and female patients 18 years of age or older had histologically proven stage IIIB or IV NSCLC which had progressed during or after treatment with at least one platinum-based combination chemotherapy regimen. Up to two prior systemic chemotherapy regimens were permitted regardless of the number of prior treatments with an epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor. All patients had unidimensionally measurable disease; evidence of disease progression within 6 months of their most recent prior systemic anticancer treatment; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1; adequate hepatic, renal, and hematologic function; and had provided informed consent. Patients were excluded if they had had a grade 3 hemorrhage, based on the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), or gross hemoptysis (> 5 mL of blood per episode and > 10 mL of blood/d) less than 4 weeks before beginning treatment. Previous treatment with antiangiogenic agents was not permitted. Additional reasons for exclusion included uncontrolled hypertension; diagnosis of any second malignancy within the last 5 years (except for adequately treated basal cell or squamous cell skin cancer or in situ carcinoma of the cervix uteri); a history of or known brain metastases, spinal cord compression or carcinomatous meningitis or evidence of brain or leptomeningeal disease based on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans; clinically significant cardiovascular disease (severe/unstable angina, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, symptomatic congestive heart failure), pulmonary embolism or cerebrovascular accident within 12 months before study drug administration; a history of a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction that was below the lower limit of normal; or ongoing cardiac dysrhythmias (NCI CTCAE grade ≥ 2), atrial fibrillation, or prolongation of the QTc interval.

Study Design and Treatment

In this phase II, open-label, multicenter study, patients received sunitinib in 6-week cycles, comprising once-daily treatment for 4 consecutive weeks, followed by 2 weeks of no treatment (schedule 4/2). Sunitinib was self-administered orally in the morning without regard to meals at a starting dose of 50 mg/d. When required, based on individual patient tolerability, subsequent doses were adjusted to 37.5 mg/d and then to 25 mg/d by study investigators, and therapy could be interrupted or delayed for up to 4 weeks (in addition to the scheduled 2-week off-treatment period). Treatment was otherwise administered for up to 54 weeks until disease progression or withdrawal of consent occurred.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center and was carried out in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines protocol, as well as applicable local laws and regulatory requirements.

The protocol was amended to examine the efficacy and safety of continuous daily sunitinib treatment at a starting dose of 37.5 mg in an additional cohort of patients; these results will be reported separately.

Study Assessments

The primary end point of this study was the overall confirmed objective response rate (ORR), defined as the percentage of patients with confirmed complete responses (CRs) or partial responses (PRs) based on radiologic tumor assessments (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scans as appropriate) and the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria.18 Imaging scans included the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and were collected at the end of dosing in cycles 1 to 4, 6, and 8, and at study termination. Bone scans were collected at the same interval if bone metastases were present at screening, and brain and/or bone scans were performed if metastases were suspected in these regions during the study. Scans were also performed 4 weeks after observation of an initial PR for response confirmation according to RECIST criteria.

Other evaluations included medical history, physical examination (including height, weight, and vital sign measurements), laboratory tests (urinalysis, hematology, coagulation, and blood chemistry), and assessment of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, cardiac function (12-lead ECGs), and adverse events (AEs; graded using the NCI CTCAE, version 3.0).

Progression-free survival (PFS), duration of response (DR), overall survival (OS), and the 1-year survival rate were evaluated as secondary end points of the study.

Statistical Methods

On the basis of a two-stage Simon Minimax design19 with an α level of 10% and 90% power, 60 patients (39 patients in stage 1 of the study and an additional 21 patients in stage 2) were required to test the null hypothesis that the true ORR was ≤ 5% versus the alternative hypothesis that the true ORR was ≥ 15%. At least two confirmed objective responses were needed in stage 1 to allow expansion of the trial to stage 2. At the end of the study, at least six confirmed objective responses were needed to reject the null hypothesis.

Efficacy (and safety) analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of sunitinib. The number and proportion of patients who achieved an objective response (CR or PR) was summarized along with the corresponding exact two-sided 95% CI, calculated using a method based on the F distribution. PFS, DR, and OS were summarized using the Kaplan-Meier method,20 with the median event time and a two-sided 95% CI for the median provided for each end point.21 The 1-year survival rate was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and a two-sided 95% CI interval for the log(−log[1-year survival rate]) was calculated using a normal approximation and then back transformed to give a CI for the 1-year survival rate.

RESULTS

A total of 64 patients from 10 centers in the United States and Europe were enrolled onto the cohort of patients assigned to schedule 4/2 dosing in the study. Sixty-three patients received at least one dose of sunitinib. Baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1 and show a median age of 60 years, male predominance, and a good performance status and history of smoking in a majority of patients. Sixty-four percent of patients (n = 40) had been diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the lung, and 22% had been diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Stage IV disease was present in 90% of patients (n = 57). All patients received chemotherapy before study enrollment, including a platinum agent in 94% (n = 59); 60% (n = 38) of the patients had received two or more systemic treatments before study entry. The starting dose of sunitinib was 50 mg/d on schedule 4/2 for all 63 patients who received at least one dose of sunitinib. The median duration of sunitinib treatment was 11 weeks (range, 1 to 54 weeks; Table 2). No patients remain on treatment; 65% (n = 41) discontinued therapy because of disease progression; 29% (n = 18) discontinued because of an AE, and 3% (n = 2) of patients completed all nine cycles of treatment (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Sunitinib (N = 63) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. of Patients |

% | |

| Age, years | |||

| Median | 60 | ||

| Range | 33–86 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 41 | 65 | |

| Female | 22 | 35 | |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 | 28 | 4 | |

| 1 | 35 | 56 | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Ever | 50 | 79 | |

| Never | 10 | 16 | |

| Not known | 3 | 5 | |

| NSCLC histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 40 | 64 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 14 | 22 | |

| Bronchioloalveolar | 2 | 3 | |

| Large-cell carcinoma | 2 | 3 | |

| NSCLC NOS | 5 | 8 | |

| Disease stage | |||

| IIIB | 6 | 10 | |

| IV | 57 | 90 | |

| Metastatic sites | |||

| Lymph nodes | 39 | 62 | |

| Bone | 24 | 38 | |

| Pleural effusion | 15 | 24 | |

| Liver | 13 | 21 | |

| Soft tissue | 11 | 18 | |

| Adrenal gland | 7 | 11 | |

| Skin | 5 | 8 | |

| Peritoneal | 1 | 2 | |

| Other | 9 | 14 | |

| No. of prior systemic regimens | |||

| 1 | 25 | 40 | |

| 2 | 30 | 48 | |

| ≥ 3 | 8 | 13 | |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimens | |||

| 1 | 37 | 59 | |

| 2 | 23 | 36 | |

| ≥ 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| Prior treatments | 63 | 100 | |

| Platinum agent | 59 | 94 | |

| Carboplatin | 42 | 67 | |

| Cisplatin | 19 | 30 | |

| Gemcitabine | 34 | 54 | |

| Paclitaxel | 24 | 38 | |

| Docetaxel | 19 | 30 | |

| Pemetrexed | 6 | 10 | |

| EGFR inhibitor* | 21 | 33 | |

| Erlotinib | 12 | 19 | |

| Gefitinib | 10 | 16 | |

| Cetuximab | 2 | 3 | |

| Other | 9 | 14 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; NOS, not otherwise specified; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Cetuximab, erlotinib, or gefitinib.

Table 2.

Treatment Duration and Patient Disposition

| Sunitinib (N = 63) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. of Patients |

% | |

| Weeks on treatment | |||

| Median | 11 | ||

| Range | 1–54 | ||

| Treatment interruption | 15 | 24 | |

| Adverse event | 14 | 22 | |

| Other | 2 | 3 | |

| Dose reduction | 14 | 22 | |

| Reductions to 37.5 mg | 11 | 17 | |

| Reductions to 25 mg | 3 | 5 | |

| Primary reason for treatment discontinuation | |||

| Disease progression | 41 | 65 | |

| Adverse events | 18* | 29 | |

| Consent withdrawn | 2 | 3 | |

| Patient completed study per protocol | 2 | 3 | |

Includes one patient for whom the adverse event was grade 5 disease progression.

Safety/Tolerability

The most commonly reported AEs include fatigue/asthenia, pain/myalgia, nausea/vomiting, and stomatitis/mucosal inflammation. Most AEs were mild to moderate in severity (grades 1 to 2; Table 3) and did not interfere with scheduled treatment. Grade 3 or 4 AEs included fatigue/asthenia (29%), pain/myalgia (17%), dyspnea (11%), and nausea/vomiting (10%; Table 3). Grade 3 hypertension, which was reported in three patients (5%), was managed according to standard clinical practice, combined with sunitinib dose interruption and/or reduction if necessary. Lymphopenia was the most common grade 3 or 4 hematologic, treatment-emergent AE (Table 3) and occurred at grade 3 in 12 patients (20%) and at grade 4 in three patients (5%). Grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia occurred in two patients (3%) and one patient (2%), respectively; similarly, grade 3 and 4 neutropenia occurred in two patients (3%) and one patient (2%), respectively. However, no cases of febrile neutropenia were observed.

Table 3.

Treatment-Emergent, Nonhematologic, and Hematologic Adverse Events Reported by at Least 10% of Patients

| Grades 1/2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total (grade 1–4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Nonhematologic adverse event, n = 63 | ||||||||

| Fatigue/asthenia | 26 | 41 | 15 | 24 | 3 | 5 | 44 | 70 |

| Pain/myalgia | 27 | 43 | 9 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 38 | 60 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 27 | 43 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 52 |

| Stomatitis/mucosal inflammation | 25 | 40 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 43 |

| Anorexia/weight decreased | 19 | 30 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 35 |

| Dyspnea | 15 | 24 | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 35 |

| Diarrhea | 19 | 30 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 33 |

| Dysgeusia | 17 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 27 |

| Cough | 15 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 25 |

| Headache | 12 | 19 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 24 |

| Constipation | 13 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 21 |

| Peripheral edema | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 16 |

| Dizziness | 9 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 14 |

| Dyspepsia | 9 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 14 |

| Dry mouth | 8 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 13 |

| Chills | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Dehydration | 2 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Depression | 6 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Dry skin | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Hypertension | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Rash | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Skin discoloration | 7 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 11 |

| Hematologic (laboratory) adverse event, n = 59* | ||||||||

| Anemia | 34 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 58 |

| Leukopenia | 39 | 66 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 68 |

| Lymphopenia | 26 | 44 | 12 | 20 | 3 | 5 | 41 | 69 |

| Neutropenia† | 26 | 44 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 49 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 29 | 49 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 32 | 52 |

Central laboratory data available for 59 of 63 patients.

No cases of febrile neutropenia were reported.

Transient dose interruption occurred in 15 patients (24%), and 14 patients (22%) underwent a dose reduction (to 37.5 mg in 11 patients and to 25 mg in three patients). Seventeen patients permanently discontinued sunitinib because of one or more AEs (excluding disease progression), for a total of 31 AEs leading to discontinuation. The most commonly reported AEs leading to permanent discontinuation of sunitinib included fatigue (four patients), asthenia (three patients), diarrhea (two patients), and vomiting (two patients).

A total of 19 patients died while enrolled onto the study. Disease progression was the cause of death for 13 patients, and six patients died as a result of other causes. Three hemorrhage-related deaths occurred on study, two of which were treatment-related; grade 5 pulmonary hemorrhage which was assessed as treatment-related occurred in a 62-year-old female patient with squamous cell lung cancer 7 days after the patient’s last dose of sunitinib and 27 days after her first dose. In another squamous cell lung cancer case, a 77-year-old male patient developed grade 4 pulmonary hemorrhage followed by death owing to disease progression. A cerebral hemorrhage occurred in a 73-year-old male patient with adenocarcinoma and was reported as treatment-related. This event occurred 6 days after the patient’s last dose and 20 days after his first dose of medication and was associated with the development of brain metastasis in the frontal lobe. Grade 5 hemorrhage was also reported in a 68-year-old female patient who developed an extensive hematoma of the face and arm after a failed attempt at intravenous access into the subclavian vein at a time when the patient was anticoagulated for pulmonary embolism; this event occurred 1 day after the patient’s last dose of sunitinib and 77 days after her first dose. The remaining on-study deaths were due to disseminated intravascular coagulation, pneumothorax, and stroke. The first two cases were judged by the investigator to be related to study drug.

In addition to the deaths occurring on study, 34 patients died during study follow-up, with 33 deaths attributed to progressive disease and one death resulting from traumatic injury.

Efficacy

Seven patients achieved a confirmed objective response (all PRs), giving an ORR of 11.1% (95% CI, 4.6% to 21.6%). An additional 18 patients (28.6%) had a best response of stable disease for 8 weeks or longer. The median DR was 21.2 weeks (range, 4.4+ to 36.3+ weeks), and the median duration of stable disease was 22.1 weeks (range, 10.1 to 46.3 weeks).

Baseline characteristics of the seven patients with a confirmed PR are shown in Table 4 and are generally representative of the larger patient population. Most of the patients with a PR had a history of smoking, stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung, and had previously received treatment with a platinum-based doublet. Interestingly, five of the seven responses were observed in women.

Table 4.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Tumor Response to Sunitinib

| Age (years) |

Sex | Smoking Status | Stage | Histology | Chemotherapy Regimens | Sites of Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | Female | Ex-smoker | IV | Squamous cell carcinoma | Carboplatin/gemcitabine | Primary tumor, liver, bone, aortopulmonary lymph nodes |

| 56 | Female | Ex-smoker | IV | Adenocarcinoma | Carboplatin/gemcitabine | Local recurrence, liver, bone, renal |

| 58 | Male | Current smoker | IIIB | Adenocarcinoma | Cisplatin/gemcitabine | Primary tumor, local recurrence, paratracheal lymph nodes |

| 58 | Female | Ex-smoker | IV | Adenocarcinoma | Carboplatin/paclitaxel, docetaxel | Primary tumor, local recurrence, lung, hilar and prevascular lymph nodes |

| 69 | Female | Lifelong nonsmoker | IV | Adenocarcinoma | Cisplatin/gemcitabine, carboplatin/paclitaxel (×2) | Primary tumor, lung |

| 55 | Female | Ex-smoker | IV | Adenocarcinoma | Carboplatin/gemcitabine/bortezomib, pemetrexed | Primary tumor, lung |

| 70 | Male | Ex-smoker | IV | Adenocarcinoma | Carboplatin/cetuximab | Primary tumor, local recurrence, lung, paratracheal lymph nodes |

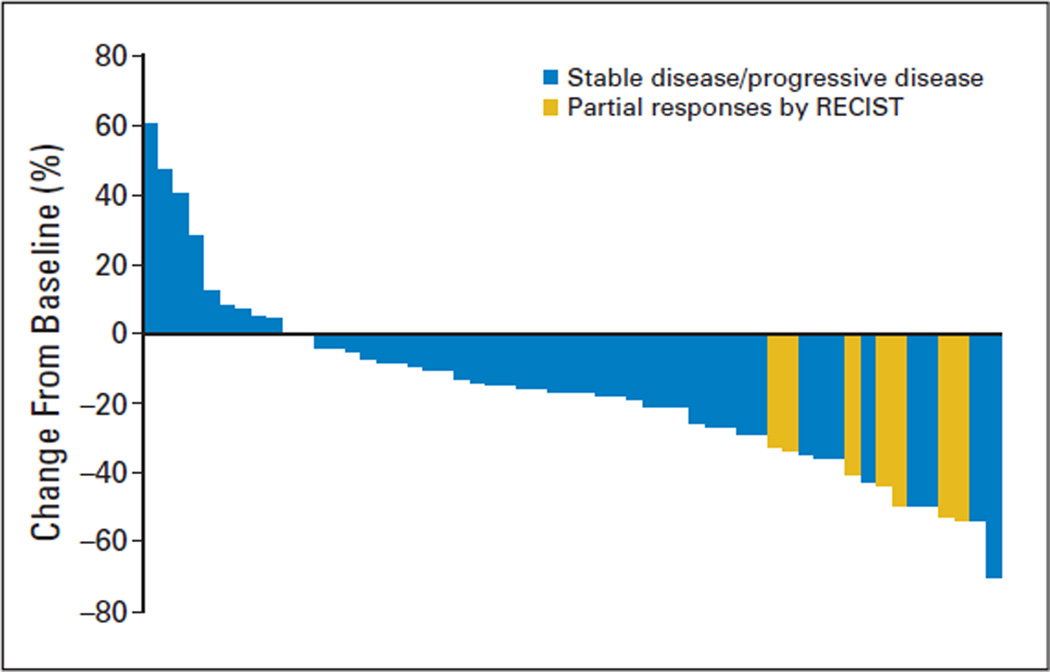

Some degree of target lesion shrinkage was observed in the majority of the patients (44 of 63 patients; 70%). Tumor assessments performed on-study revealed 15 patients (24%) with a maximum decrease in target lesion measurements of at least 30% when compared with screening. In addition to the seven patients with a confirmed PR, one patient was unassessable because of the absence of restaging bone scan, but this patient otherwise met RECIST criteria for a confirmed PR. The other seven patients did not meet RECIST criteria for a confirmed PR as a result of disease progression at the subsequent imaging assessment (n = 6) or death before reimaging (n = 1). Disease progression was documented with a new lesion (n = 3, one patient each with bone, adrenal, and brain metastasis), target lesion measurement increase (n = 1), target lesion measurement increase and progression of a nontarget lesion (n = 1), and target lesion measurement increase and development of a new lesion (n = 1). Best response for target lesion(s) by patient is shown in the waterfall plot in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Best response for target lesions by patient, based on maximal percentage of tumor reduction. Patients experiencing a partial response according Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) are shown in yellow bars, while those with stable disease or progressive disease are shown in blue bars. (Some patients withdrew from the study before their first postscreening scan.)

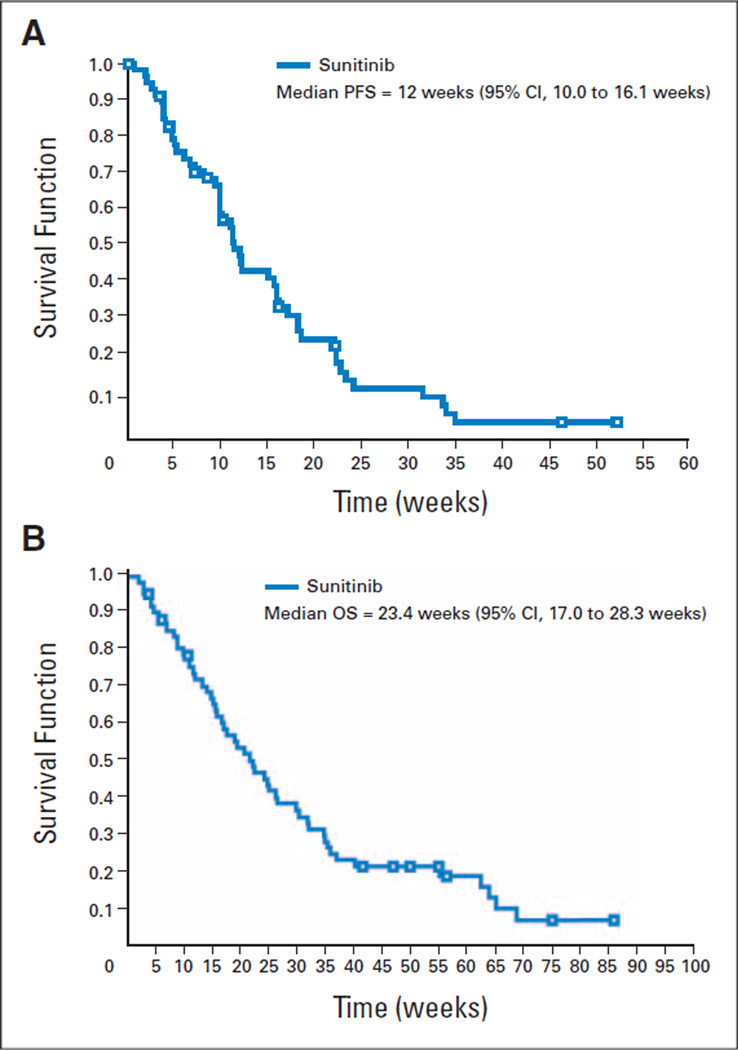

Median PFS was 12.0 weeks (95% CI, 10.0 to 16.1 weeks; Fig 2A), and median OS was 23.4 weeks (95% CI, 17.0 to 28.3 weeks; Fig 2B). The 1-year survival rate was 20.2% (95% CI, 10.0% to 30.4%).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of (A) progression-free survival (PFS) and (B) overall survival (OS).

DISCUSSION

In NSCLC, as inmost solid tumors, it is believed that there is multilevel cross-stimulation among targets along several pathways of signal transduction that lead to malignancy. As most first-generation targeted agents act by blocking only one of these pathways, other pathways are allowed to act as salvage or escape mechanisms for cancer cells. Therefore, a logical approach would involve a single agent with multiple targets, which, in combination with chemotherapy, may provide a more complete therapeutic benefit. Such agents include a number of small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target several receptor tyrosine kinases associated with NSCLC and activated vascular endothelial cells.

The potential advantages of multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors over single-targeted agents may include convenience of multiactivity in single agent, higher likelihood of single-agent activity, direct targeting of both tumor and blood vessels, and potentially lower costs. These possible benefits must be weighed against potential disadvantages; for instance, the inhibition of each target may not be equally effective at the relevant dose used in patients, and the potential exists for different toxicity profiles for multitargeted agents compared with single-targeted agents.

Preclinical data have shown benefits for combining VEGFR and PDGFR inhibition in terms of tumor regression in the H266 human lung carcinoma model.22 The antitumor activity of single-agent sunitinib in mouse models is similar to that observed with the combination of a PDGFR/kit inhibitor with a selective VEGFR inhibitor and superior to either agent administered alone.22 These data support the importance of dual inhibition of VEGFR and PDGFR for antitumor activity. The importance of these signaling pathways has been further evaluated in patients with NSCLC, where aberrant VEGF and PDGF signal transduction is associated with decreased survival and tumor angiogenesis.2,3

Clinical trials with the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab have confirmed the importance of VEGF pathways in advanced NSCLC, showing that the addition of an anti-VEGF agent to chemotherapy improves survival when compared with chemotherapy alone.8 However, the importance of PDGF pathways is increasingly recognized.3–5 In the present study, sunitinib, an inhibitor of both VEGFR and PDGFR, has demonstrated single-agent activity in patients with previously treated, advanced NSCLC with an ORR of 11.1%. Similar response rates in this disease setting have not been previously reported for an antiangiogenic agent, suggesting that the broader and/or more complete inhibition of angiogenic pathways of sunitinib can effect greater antitumor activity.

As shown in Fig 1, the majority of patients demonstrated some reduction in the target lesion measurements while enrolled onto the study. However, the activity of sunitinib and other antiangiogenic agents may still be underestimated by RECIST criteria. Some patients who showed small changes in tumor measurements demonstrated tumor cavitation, suggesting clinical efficacy might not always result in decreases in target lesion measurements.

Docetaxel, pemetrexed, and erlotinib are approved for patients with recurrent NSCLC.23–25 Single-agent treatment with docetaxel results in an ORR of 6.7% to 10.8% and a median OS of 5.5 to 7.5 months.23,26 Pemetrexed and erlotinib have shown similar response rates.24,25 The clinical activity of sunitinib observed in the current study seems similar to the currently approved agents despite the evaluation of sunitinib in a more heavily pretreated patient population, with the majority (60%) of the sunitinib-treated patients having received two or more prior systemic treatment regimens.

The AEs observed in this study were either expected for this patient population or similar to those reported in other trials of sunitinib.15–17 Sunitinib was generally well tolerated, with the majority of AEs being grade 1 or 2 in nature. Preliminary analysis of the additional patients (n = 47) treated on the continuous schedule of sunitinib at 37.5 mg/d suggest a lower rate of severe fatigue.27,28 In addition, evidence suggests that hemorrhage seems to occur with antiangiogenic agents in NSCLC,29 as described in this study. Hematologic toxicity was minimal, but careful phase I/II trials of sunitinib combined with standard cytotoxic agents must be undertaken to be sure sunitinib does not worsen hematologic toxicity, as has previously been observed with bevacizumab.8

In conclusion, this study shows that sunitinib has promising single-agent activity and a manageable tolerability profile in patients with recurrent NSCLC. The clinical activity of sunitinib in this heavily pretreated population of patients was similar to that of currently approved agents. This study has been amended to evaluate an alternative sunitinib treatment schedule comprising continuous once-daily dosing at 37.5 mg/d.27 Given the preliminary evidence of sunitinib activity in NSCLC, additional studies are currently underway, including trials of sunitinib in combination with chemotherapy or molecularly targeted agents and trials evaluating sunitinib as maintenance therapy in those patients who derive clinical benefit from first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Acknowledgment

Editorial and medical writing assistance was provided by ACUMED (Tytherington, United Kingdom) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

This study was supported by funding from Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 43rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 1–5, 2007, Chicago, IL; the 8th Annual Lung Cancer Conference, June 27–30, 2007, Maui, HI; the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 2–6, 2006 Atlanta, GA (Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 24:364s, 2006 [abstr 7001]); and the 31st European Society for Medical Oncology Congress, September 29-October 3, 2006, Istanbul, Turkey.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Lesley Tye, Pfizer (C); Paulina Selaru, Pfizer (C); Richard C. Chao, Pfizer (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: Julie R. Brahmer, Eli Lilly (C), Cephalon (C), Genentech (C); Chandra P. Belani, Pfizer (C); Giorgio V Scagliotti, Eli Lilly (C) Stock Ownership: Lesley Tye, Pfizer; Paulina Selaru, Pfizer; Richard C. Chao, Pfizer Honoraria: Mark A Socinski, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis; Heidi H. Gillenwater, Genentech; Giorgio V. Scagliotti, Eli Lilly, Sanofi-Aventis, Roche Research Funding: Mark A. Socinski, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis; Julie R. Brahmer, Wyeth, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Medarex; Ramaswamy Govindan, Pfizer; Heidi H. Gillenwater, Pfizer; Giorgio V. Scagliotti, Eli Lilly Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mark A. Socinski, Chandra P. Belani, Lesley Tye, Richard C. Chao

Provision of study materials or patients: Mark A. Socinski, Silvia Novello, Julie R. Brahmer, Rafael Rosell, Jose-Miguel Sanchez -Torres, Chandra P. Belani, Ramaswamy Govindan, James N. Atkins, Cinta Pallares, Giorgio V. Scagliotti

Collection and assembly of data: Mark A. Socinski, Silvia Novello, Chandra P. Belani, Heidi H. Gillenwater, Cinta Pallares, Lesley Tye, Richard C. Chao, Giorgio V. Scagliotti

Data analysis and interpretation: Mark A. Socinski, Silvia Novello, Julie R. Brahmer, Chandra P. Belani, Lesley Tye, Paulina Selaru, Richard C. Chao, Giorgio V. Scagliotti

Manuscript writing: Mark A. Socinski, Silvia Novello, Chandra P. Belani, Lesley Tye, Richard C. Chao, Giorgio V. Scagliotti

Final approval of manuscript: Mark A. Socinski, Silvia Novello, Julie R. Brahmer, Rafael Rosell, Jose M. Sanchez -Torres, Chandra P. Belani, Ramaswamy Govindan, James N. Atkins, Heidi H. Gillenwater, Richard C. Chao, Giorgio V. Scagliotti

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan A, Yu CJ, Kuo SH, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor 189 mRNA isoform expression specifically correlates with tumor angiogenesis, patient survival, and postoperative relapse in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:432–441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, O’Byrne KJ, et al. Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor expression correlates with tumour angiogenesis and prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:477–481. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Byrne KJ, Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor and angiogenesis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1427–1432. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shikada Y, Yonemitsu Y, Koga T, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-AA is an essential and autocrine regulator of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7241–7248. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepherd FA. Angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(suppl 3):S81–S89. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fehrenbacher L, O’Neil VJ, Belani CP, et al. A phase II, multicenter, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of bevacizumab (Avastin) in combination with either chemotherapy (docetaxel or pemetrexed) or erlotinib hydrochloride (Tarceva) compared with chemotherapy alone for treatment of recurrent or refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Slide presentation at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; June 2–6; Atlanta, GA. Available at http://www.asco.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, et al. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: Determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Farrell AM, Abrams TJ, Yuen HA, et al. SU11248 is a novel FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2003;101:3597–3605. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray LJ, Abrams TJ, Long KR, et al. SU11248 inhibits tumor growth and CSF-1R-dependent osteolysis in an experimental breast cancer bone metastasis model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:757–766. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006873.65590.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toner GC, Mitchell PL, De Boer R, et al. PET imaging study of SU11248 in patients with advanced malignancies. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:191. (abstr 767) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, et al. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA. 2006;295:2516–2524. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casali PG, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, et al. Updated results from a phase III trial of sunitinib in GIST patients (pts) for whom imatinib (IM) therapy has failed due to resistance or intolerance. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006;24:523s. (abstr 9513) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brookmeyer R, Crowley JJ. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potapova O, Laird AD, Nannini MA, et al. Contribution of individual targets to the antitumor efficacy of the multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor SU11248. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1280–1289. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-03-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens: The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2354–2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brahmer J, Govindan R, Novello S, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous daily sunitinib dosing in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Results from a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):7542. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Socinski MA, Novello S, Sanchez JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in a multicenter phase II trial of previously treated, advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Ann Oncol. 2006;17(suppl 9):729PD. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatzemeier U, Blumenschein G, Fosella F, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent sorafenib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006;24:18S. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0541. (abstr 7002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]