To the Editor: Dirofilaria repens is a vector-borne, zoonotic, filarial nematode that infects dogs, cats, and humans. In humans, D. repens worms cause subcutaneous dirofilariasis, characterized by the development of benign subcutaneous nodules that mimic skin carcinomas (1), and ocular dirofilariasis in orbital, eyelid, conjunctival, retroocular, and intraocular locations (2). Intraocular and retroocular dirofiliariasis causes considerable damage and discomfort in patients from the presence of the worms and from their surgical removal (3). Here, we report a retroocular D. repens nematode infection in a patient in Russia that illustrates the difficulties in clinical management and the inherent risks of surgical procedures to remove the worms.

A 20-year-old woman living in Rostov-na-Donu in southwestern Russia who had never traveled outside the city sought ophthalmologic consultation for pain and skin redness and swelling in the inner corner of the upper left eyelid. Swelling migrated successively to the temporal area, the lower eyelid, and the inner corner of the lower eyelid. The patient had no other ocular signs or symptoms, and her general condition was otherwise good. Results of ophthalmologic examination and routine laboratory tests were within normal limits. Four days of treatment with cefotaxime resulted in the remission of signs and symptoms. Approximately 2 months later, swelling in the inner corner of the upper eyelid appeared again, affecting the whole upper eyelid, without itching or tenderness. Allergies were diagnosed; cetirizine was administered for 4 days, and the signs remitted at the third day of treatment. One month later, marked upper left eyelid swelling occurred, resulting in ptosis. Cetirizine was prescribed again; edema subsided after 4 days of treatment but relapsed in the following 3–4 days.

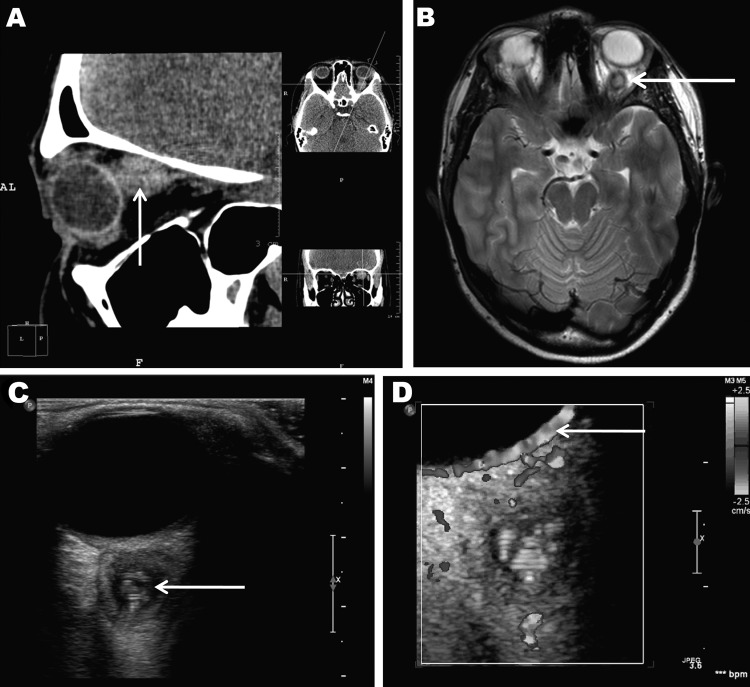

At least 4 subsequent relapses occurred; thus, a computed tomographic scan of the paranasal sinuses and orbits was performed, 4 months after signs and symptoms began (Figure, panel A). The scan detected a soft tissue structure, 12 × 13 × 14 mm, behind the left eyeball, adjacent to and medially dislodging the optic nerve. No other abnormalities were found in the visible area of the brain and sinuses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed 1 month later (Figure, panel B) corroborated the presence of a cyst-like structure with an irregular, rounded shape and clear, smooth borders closely adhered to the eyeball and optic nerve. T2-weighted images showed that the lesion had a high-density core but the surrounding tissue was low density. Adjacent to the lesion, the retrobulbar tissue was slightly swollen, the optic nerve was displaced medially and downward, and the adjacent upper muscle was displaced medially and upward. The diagnosis was evidence of a retroocular cystic lesion in the left orbit with a well-defined capsule and high-density but heterogeneous core structure.

Figure.

Retroocular nodule of a Dirofilaria repens worm detected in a 20-year-old woman, Rostov-na-Donu, Russia. The cyst (arrows) is shown by computed tomography scan (A) and magnetic resonance imaging (B). Ultrasonography images (C) show a worm-like structure inside the cyst (arrow), and color Doppler imaging (D) shows marginal vascularization of the lesion).

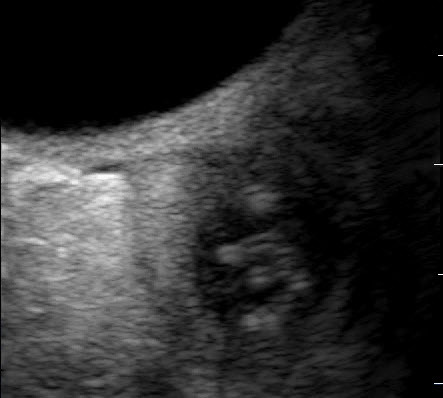

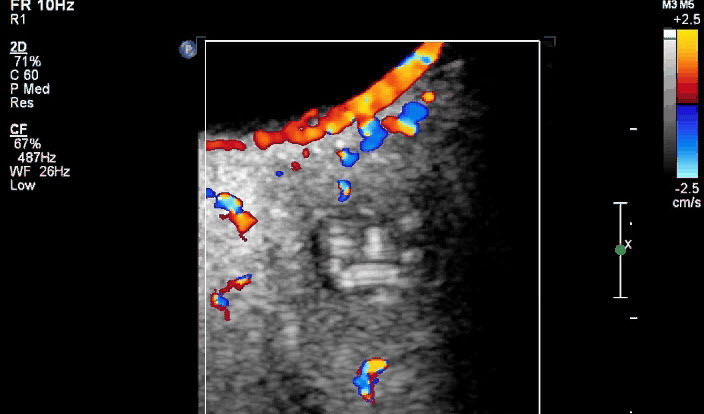

High-resolution ultrasound examination (Figure, panel C) revealed a well-defined, 3-mm, cyst-like wall containing fluid and dense, coiled-twisted linear internal structures that appeared to be actively moving (Video 1). Color Doppler examination (Figure, panel D; Video 2) revealed blood vessels in the wall but not inside the cystic structure. These additional examinations led to a diagnosis of a retroocular parasitic cyst in the left orbit, most likely a Dirofilaria spp. parasite. The parasitic cystic nodule was removed during a transpalpebral orbitotomy. A live, adult roundworm, 87 × 0.6 mm, was discharged from the cyst. Conventional PCR identified the roundworm as D. repens (data not shown).

Video 1.

High-resolution ultrasound examination images showing a Dirofilaria repens worm actively moving inside retroocular nodule in a 20-year-old woman, Rostov-na-Donu, Russia.

Direct Video Link: http://streaming.cdc.gov/vod.php?id=eff01b6f9bbe41f1ea318db3d6e66f9220121218092846890

Video 2.

Color Doppler examination images showing the blood flow only outside the retroocular nodule in which the movement of a Dirofilaria repens worm is detected in a 20-year-old woman, Rostov-na-Donu, Russia.

Direct Video Link: http://streaming.cdc.gov/vod.php?id=e439085f91fad2cea4015df84bd7175220121219104320609

Although human subcutaneous Dirofilaria spp. nodules are benign, their detection may raise suspicion for a malignant tumor; thus, differential diagnosis is the key point in the management of human dirofilariasis (4). The case we described illustrates the difficulties of diagnosis when worms are in deep locations and patients experience unspecific and even unusual signs. These confounders resulted in a lengthy diagnostic procedure, with consequent detrimental physical and psychological effects on the patient. Even though the final diagnosis determined that the nodule was nonmalignant, its anatomic location required aggressive surgical intervention to remove it.

D. repens nematodes are spreading in Europe from the south toward the north and east (5–7) as a consequence of global warming, and prediction models have suggested incidence is increasing among animal and human hosts (3). Consequently, human ocular dirofilariasis will probably be found with increasing frequency in the future. Our experience illustrates that dirofilariasis should be included in the differential diagnosis of any nodule, independent of its anatomic location and the signs and symptoms shown by the patient. Moreover, ultrasonography represents a noninvasive technique that enables rapid preoperative identification of the parasitic origin of the nodules, thus avoiding unnecessary diagnostic delays. This technique is used for the diagnosis of cardiopulmonary dirofilariasis in animals (8) but has been used only sporadically for human dirofilariasis (9,10), which is habitually diagnosed postoperatively, after the surgical removal of the nodules or worms (1).

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ilyasov B, Kartashev V, Bastrikov N, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Simón F. Delayed diagnosis of dirofilariasis and complex ocular surgery, Russia [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1902.121388

References

- 1.Pampiglione S, Canestri Trotti G, Rivasi F. Human dirofilariasis due to Dirofilaria (Nochtiella) repens: a review of world literature. Parassitologia. 1995;37:149–93 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simón F, Siles-Lucas M, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Mellado I, Carretón E, et al. Human and animal dirofilariasis. The emergence of a zoonotic mosaic. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:507–544 . 10.1128/CMR.00012-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genchi C, Kramer LH, Rivasi F. Dirofilarial infection in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1307–17 . 10.1089/vbz.2010.0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simón F, Morchón R, González-Miguel J, Marcos-Atxutegi C, Siles-Lucas M. What is new about animal and human dirofilariosis? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:404–9 . 10.1016/j.pt.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genchi C, Rinaldi L, Cascone C, Mortarino M, Cringoli G. Is heartworm disease really spreading in Europe? Vet Parasitol. 2005;133:137–48 . 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer LH, Kartashev VV, Grandi G, Morchón R, Nagornii SA, Karanis P, et al. Human subcutaneous dirofilariasis, Russia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:150–2 . 10.3201/eid1301.060920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kartashev V, Batashova I, Kartashov S, Ermakov A, Mironova A, Kuleshova Y, et al. Canine and human dirofilariosis in the Rostov region (southern Russia). Vet Med Int. 2011;•••:685713 . 10.4061/2011/685713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venco L, Vezzoni A. Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) disease in dogs and cats. In: Simón F, Genchi C, editors. Heartworm infection in humans and animals. Salamanca (Spain): Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca; 2001. p. 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Reilly MAR, O’Reilly PMR, Kace G. Breast infection due to dirofilariasis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1097–9 . 10.1007/s003300101024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Boysson H, Duhamel C, Heuzé-Lecornu L, Bonhomme J, de la Blanchardière A. Human dirofilariasis: a new French case report with Dirofilaria repens. Rev Med Interne. 2012;33:e19–21 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]