Abstract

Aim

Resistance of cancer cells to hyperthermic temperatures and spatial limitations of nanoparticle-induced hyperthermia necessitates the identification of effective combination treatments that can enhance the efficacy of this treatment. Here we show that novel polypeptide-based degradable plasmonic matrices can be employed for simultaneous administration of hyperthermia and chemotherapeutic drugs as an effective combination treatment that can overcome cancer cell resistance to hyperthermia.

Method

Novel gold nanorod elastin-like polypeptide matrices were generated and characterized. The matrices were also loaded with the heat-shock protein (HSP)90 inhibitor 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), currently in clinical trials for different malignancies, in order to deliver a combination of hyperthermia and chemotherapy.

Results

Laser irradiation of cells cultured over the plasmonic matrices (without 17-AAG) resulted in the death of cells directly in the path of the laser, while cells outside the laser path did not show any loss of viability. Such spatial limitations, in concert with expression of prosurvival HSPs, reduce the efficacy of hyperthermia treatment. 17-AAG–gold nanorod–polypeptide matrices demonstrated minimal leaching of the drug to surrounding media. The combination of hyperthermic temperatures and the release of 17-AAG from the matrix, both induced by laser irradiation, resulted in significant (>90%) death of cancer cells, while ‘single treatments’ (i.e., hyperthermia alone and 17-AAG alone) demonstrated minimal loss of cancer cell viability (<10%).

Conclusion

Simultaneous administration of hyperthermia and HSP inhibitor release from plasmonic matrices is a powerful approach for the ablation of malignant cells and can be extended to different combinations of nanoparticles and chemotherapeutic drugs for a variety of malignancies.

Keywords: 17-AAG, cancer, combination treatment, gold nanorod, heat-shock inhibitor, hyperthermia, photothermal ablation, plasmonic matrix, prostate cancer

Cancer diseases are among the leading causes of death in the USA and account for approximately one in every four deaths. Hyperthermia involves raising the temperature of malignant cells in the range of 40 to 46°C in order to induce tumor ablation [1], and is receiving increased attention as an adjunctive treatment option for cancer [2]. Cellular injury/death at temperatures above 43°C is attributed to protein denaturation triggered by these elevated temperatures [3,4]. Consequently, microwaves and radiowaves [5,6], magnetic heating [7] or ultrasound [8] have been employed for hyperthermic ablation of cancer cells.

The ability to generate high temperatures at a desired site with externally tunable control holds significant promise for cancer therapy compared with whole-body hyperthermia. Nanomaterials localized at the tumor in vivo can be subjected to laser irradiation from an external source, leading to the selective localization of the hyperthermic treatment [9]. In addition to gold nanoshells [10] and nanocages [11], gold nanorods (GNRs) [12–14] are attractive candidates for ablation of tumors. Recently, photothermolysis, strong near-infrared absorbance and magnetic functionality were also demonstrated using 30-nm gold/iron oxide nanoclusters for application in combined imaging and therapy [15]. Properties such as biocompatibility, ease of functionalization and tunable near-infrared light absorption, make gold nanoparticles promising in novel theranostic platforms [16].

Suboptimal administration of hyperthermia leads to thermotolerance in cancer cells, which, in part, is caused by the induction of the heat-shock response mediated by heat-shock proteins (HSPs) [17]. In particular, HSP27, 72 and 90 play a significant role in enabling the survival of cancer cells to hyperthermic conditions [18,19]. In addition, spatial limitations and suboptimal administration associated with hyperthermia can lead to selection of resistant tumor clones, which further complicates therapy. As a result, therapeutic strategies that can synergistically enhance the efficacy of hyperthermic ablation (e.g., by overcoming HSP resistance) can help advance the potential of this approach in cancer therapy.

We demonstrate, for the first time, that GNRs can be interfaced with cysteine-containing elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) resulting in bio-compatible and degradable plasmonic matrices that can be employed to effectively administer hyperthermic treatment to cancer cells. Laser irradiation of cancer cells cultured on top of the matrix led to the death only of cells in the path of the laser, revealing spatial limitations associated with nanoparticle-induced hyperthermia. The chemotherapeutic drug 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-AAG), an inhibitor of HSP90 investigated in clinical trials [20,21], was incorporated in the matrix. Laser irradiation was employed for simultaneous hyperthermic treatment of the cancer cells and for inducing the release of 17-AAG from the matrix under these elevated temperatures, in order to synergistically administer hyperthermia and chemotherapy (17-AAG), resulting in more than 90% loss of cancer cell viability.

Experimental

Materials

Sodium borohydride, powder, reagent grade, no less than 98.5%, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 95%, gold (III) chloride tri-hydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O), +99.9%, L-ascorbic acid, reagent grade were purchased from Sigma. Crystalline silver nitrate was purchased from Spectrum and dithiothreitol (DTT) was purchased from EMD. All materials were used as received without further purification.

GNR synthesis

Gold nanorods were synthesized using the seed-mediated method as described by El-Sayed et al. [22]. Briefly, the seed solution was prepared by adding 0.6 ml of iced-water-cooled sodium borohydride (0.01 M) to reduce a solution of 5 ml (0.2 M) of CTAB in 5 ml (0.0005 M) auric acid with vigorous stirring. The growth solution was prepared by reducing 5 ml (0.2 M) CTAB in 5 ml (0.001 M) auric acid containing 280 μl (0.004 M) silver nitrate with 70 μl (0.0788 M) L-ascorbic acid solution. Seed solution (12 μl) was introduced to 10 ml of growth solution, which resulted in the generation of GNRs after 4 h of continuous stirring. The nanorods were centrifuged once, the supernatant was removed, and resuspended in deionized (DI) water to remove extra free CTAB molecules. This method was employed for generating GNRs that possessed absorbance maxima (λmax) in the near-infrared region of the light absorption spectrum.

Synthesis, expression & purification of cysteine-containing ELPs

Cysteine-containing ELPs, C8ELP and C12ELP, were generated via the recursive directional ligation method described previously [23] . C8ELP and C12ELP, respectively, contain 8 and 12 cysteine residues in the sequence: MVSACRGPG-[VG VPGVG VPGVG VPGVG VPGVG VPG]8-[VG VPGVG VPGVG VPGCG VPGVG VPG]8(or 12)-WP. Briefly, oligonucleotides encoding the ELPs were cloned into pUC19 vector, followed by cloning into a modified version of the pET25b+ expression vector at the sfiI site. Escherichia coli BLR(DE3) (Novagen) was used as a bacterial host. Both C8ELP and C12ELP were expressed, purification lyophilized and stored at room temperature, as described previously [23].

Determination of transition temperature

The transition temperatures (Tt) of C8ELP and C12ELP were characterized by monitoring the absorbance at 610 nm as a function of temperature with an UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beckman DU530) in 0.5× phosphate-buffered solution (PBS). Briefly, 1 ml of C8ELP (0.5 mg/ml in 0.5× PBS) and 1 ml of C12ELP (1 mg/ml in 0.5× PBS) were prepared and placed in 1.5-ml disposable cuvettes. The temperature of CnELP (n: the number of cysteines in the ELP repeat sequence; n = 8/12) was tuned by placing the CnELP-contained cuvette into a Precision 288 Digital Water Bath (Thermo Scientific) and was recalibrated by FLUKE 54 II (Type K) thermometer before absorbance measurement. The absorbance of CnELP was monitored at 610 nm with an UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beckman DU530) immediately after withdrawing the cuvette out of the water bath. The Tt is defined as the temperature at which the absorbance of CnELP solution reaches 50% of the maximum value. The temperature response of the C8ELP and C12ELP indicated Tt values of 31.3 and 30.5°C, respectively.

Generation of CnELP–GNR nanoassemblies

Two different ELPs, C8ELP and C12ELP, containing 8 and 12 cysteines in the ELP repeat sequence, respectively, were employed in the current study. Cysteine-containing ELPs were self-assembled on GNRs (CTAB–GNRs) whose peak absorbance (λmax) was at 800 nm (Supplementary Figure 1, see online www.future-medicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/nnm.10.133). ELPs were self-assembled on GNRs overnight at 4°C, leading to formation of the nanoassemblies (CnELP–GNR assemblies) via gold-thiol bonds. Briefly, 1 ml of CnELP (2 mg/ml in 1× PBS) was mixed overnight with 1 ml of GNR (optical density at 800 nm = 0.5) dispersion in DI water at 4°C to form a 2-ml CnELP–GNR dispersion (1 mg/ml in 0.5× PBS). Prior to self-assembly, 20 mg of reductacryl resin (EMD Biosciences, Inc.) was added to ELP (1 ml) solution for 15 min in order to reduce the cysteines in the polypeptide [24]. Reduced ELP was separated from the resin by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and immediately added to GNRs at a volumetric ratio of 1:1 and stirred overnight at room temperature. Equivalent concentrations of GNRs (without self-assembled CnELP) and CnELP (without GNRs) were used as controls in the experiments. CnELP (2 mg/ml in 1× PBS) was added into DI water at a 1:1 volume ratio, to form CnELP solution (1 mg/ml in 0.5× PBS; CnELP alone). GNRs in DI water (1 ml; λmax= 800 nm; optical density at 800 nm = 0.5) were added to an equal volume (1 ml) of 1× PBS in order to bring the final concentration to 0.5× PBS (GNR alone).

Formation of CnELP–GNR matrices

A volume of 1 ml C8ELP–GNR, and C12ELP–GNR solutions (1 mg/ml, 0.5× PBS, optical density: 0.25), in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes, was incubated in a 37°C water bath for 6 h in order to allow the phase separation of GNR–CnELP, resulting in the formation of the matrix at the bottom of the tubes. The matrices were subsequently cooled and stored at room temperature. GNRs (without self-assembled CnELP) and CnELP (without GNR) solutions were used as controls in the experiment. To study the kinetics of matrix formation, the absorption spectra of the supernatant of both C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR dispersions were determined at different times using a temperature-controlled plate reader (Biotek Synergy 2) during water heating (bath incubation) and cooling. The spectra were typically measured between 300 and 999 nm. The C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices are stable at room temperature for at least 1 month.

Dissolution of C8ELP–GNR matrices

For dissolution experiments, the PBS supernatants were removed from individual CnELP–GNP matrices and replaced with equivalent volumes of 10 mM dithiothreitol solution for 30 min at 4°C, following which, absorbance spectra were determined as a function of time in order to investigate dissolution kinetics.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

Gold nanorods and C8ELP- and C12ELP-based matrices were loaded on a germanium-attenuated total reflectance crystal, such that they covered the central area of the crystal. The sample chamber was equilibrated to approximately 4 mb pressure in order to minimize the interference of atmospheric moisture and CO2. The absorption spectrum was measured between 650 and 4,000 cm−1 using a Bruker IFS 66 v/S FT-IR spectrometer and the background spectrum was subtracted from all sample spectra, as described previously [25].

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) samples were prepared by placing CnELP–GNR matrices on a flat alumina substrate. The matrix on the substrate was allowed to dry out in open laboratory atmosphere. SEM images were obtained with an environmental field-emission SEM (PHILIPS FEI XL-30 SEM) operating an accelerating voltage of 25 kV, and several magnifications between 2500 and 20,000×.

Photothermal properties of a C12ELP–GNR matrix film

C12ELP–GNR dispersion (750 μl of 1 mg/ml in 0.5× PBS; optical density: 0.25; 4°C) in 1-mm diameter acrylic cell (homemade) was immediately incubated in 37°C, 5% CO2 environment for 3 h, in order to allow matrix formation on top of a tissue culture-treated 1.5-mm diameter cover slip originally placed at the bottom of the acrylic cell. The supernatant was removed from the acrylic cell after incubation and the absorption spectrum of the C12ELP–GNR film was determined using a plate reader (Biotek Synergy 2) at room temperature. The spectrum was measured between 300 and 999 nm at five individual times.

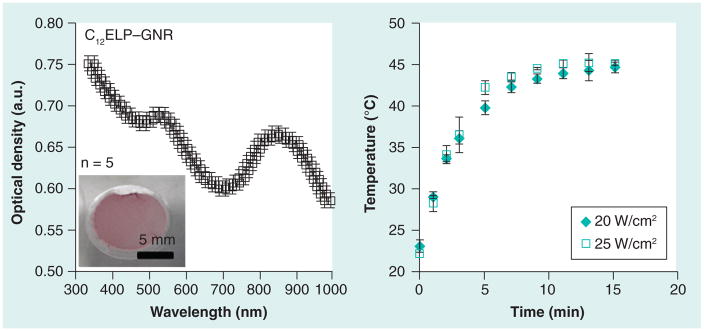

The photothermal properties of the matrix were determined using irradiation with a titanium CW sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics, Tsunami) pumped by a solid-state laser (Spectra-Physics, Millennia). Briefly, the excitation source was tuned to 850 nm in order to coincide with the longitudinal absorption maximum of the C12ELP–GNR matrix. The C12ELP–GNR matrix was placed at the bottom of a 24-well plate (Corning) with 500 μl of 1× PBS as the supernatant over the matrix. The well was irradiated with laser light at 850 nm at power densities of 20 or 25 W/cm2 for 15 min, and the dispersion temperature was monitored by FLUKE 54 II (Type K) thermocouple during laser exposure. Controls with only 500 μl of 1× PBS solution in 24-well plates (i.e., without C12ELP–GNR film) were carried out; temperature remained invariant at 24 ± 0.5°C after 15 min laser exposure in this case.

Formation of 17-AAG-loaded C12ELP–GNR matrix film (24-well plate)

C12ELP–GNR dispersion (750 μl of 1 mg/ml, 0.5× PBS, optical density: 0.25 at 4°C), containing 750 μg of 17-AAG (LC Laboratories, MA,USA) was placed in the 1-mm diameter acrylic cell, and immediately transferred to an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) for 3 h, allowing phase separation and formation of 17-AAG-loaded C12ELP–GNR (17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR) matrix on top of a tissue culture-treated 1.5-mm diameter cover slip. While 6 h were previously employed for generating C12ELP–GNR matrices (without 17-AAG), analysis of matrix formation kinetics indicated that 3 h were sufficient to generate the matrix. As a result a 3-h incubation period was used for generating 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices in order to reduce processing times. Following incubation, the supernatant, containing free 17-AAG molecules, was removed from the acrylic cell after 3 h, and assayed for concentration using absorbance analysis. The amount of 17-AAG encapsulated in the matrix was determined from a mass balance on the drug. Briefly, absorbance values of known concentrations of 17-AAG at 335 nm were employed to generate a standard calibration curve. Following matrix formation, the concentration of 17-AAG in the supernatant was then back-calculated based on the absorbance and the calibration curve. Since the initial amount of 17-AAG is known, the amount encapsulated in the matrix was calculated as the difference of 17-AAG before and after encapsulation. The absorption spectrum of the 17-AAG encapsulated C12ELP–GNR film was determined at room temperature using a plate reader (Biotek Synergy 2) with five individual measurements. A peak at 335 nm was used to detect encapsulation of the drug.

Release of 17-AAG from 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices

Drug (17-AAG)-loaded C12ELP–GNR matrices were prepared as described above and placed in a 24-well plate with 500 μl of 1× PBS. The diffusional release of 17-AAG from the matrix was monitored for 24 h. The laser beam was tuned to 2 mm in diameter for all near-infrared irradiation-triggered drug-release studies. The first laser irradiation lasted for 5 min (850 nm, 25 W/cm2). Five subsequent laser irradiations (850 nm, 25 W/cm2) lasted for 10 min, followed by a 20-min period without laser irradiation each. The temperature profile during the 10-min laser exposure was monitored using a K-type thermocouple.

Cell culture

The PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cell line [26] was a generous gift from Michel Sadelain of the Memorial Sloan Cancer Center (NY, USA). RPMI 1640 with L-glutamine and HEPES (RPMI-1640 medium), pen-strep solution: 10,000 units/ml penicillin and 10,000 μg/ ml streptomycin in 0.85% NaCl, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Hyclone. Serum-free medium is RPMI-1640 medium plus 1% antibiotics. Serum-containing medium is serum-free medium plus 10% FBS. Cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C using RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% antibiotics (10,000 units/ml penicillin G and 10,000 μg/ml streptomycin).

Cell culture & laser irradiation on C12ELP–GNR matrices

C12ELP–GNR and 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices on tissue culture cover slips were prepared as described previously. Prior to cell culture, the matrices were pretreated with 500-μl serum containing media in a 24-cell culture well plate (Corning) overnight in order to promote cell attachment. The serum-containing media was removed after incubation and the matrix-coated cover slips were washed twice with fresh serum-containing media. PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cells were seeded on top of the matrices in several wells with a density of 150,000 cells/well and allowed to attach for 24 h at 37°C, in a 5% CO2 incubator. For the laser irradiation experiment, the excitation source was tuned to 850 nm in order to coincide with the longitudinal absorption maximum of the C12ELP–GNR film. Matrices with PC3-PSMA cells were exposed to laser irradiation at 850 nm at a power density of 25 W/cm2 for 7 min (no laser exposure for the control samples). The solution temperature was monitored by a FLUKE 54 II (Type K) thermocouple during laser exposure. Fluorescence-based Live/Dead® assay was employed to investigate cancer cell viability 24 h after laser irradiation. Briefly, cells were treated with 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (Invitrogen) and 2 μM calcein AM (Invitrogen) for 30 min, and imaged using Zeiss AxioObserver D1 inverted microscope (10 × X/0.3 numerical aperture objective; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Germany). Dead/dying cells with compromised nuclei stained positive (red) for EthD-1, viable/live cells stained green for calcein AM.

Results & discussion

Cysteine-containing ELPs (CnELPs; n= 8 or 12, indicating 8 or 12 cysteines in the ELP repeat sequence) were synthesized via recursive directional ligation, expressed in E. coli, and purified, as described previously [23]. The transition temperatures (Tt) [27] of C8ELP and C12ELP were determined to be 31.3 and 30.5°C, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2). CTAB–GNRs, with maximum peak absorbance at 800 nm in the near-infrared region of the absorption spectrum (Supplementary Figure 1), were generated using the seed-mediated growth method [22]. The cysteines in CnELPs were first reduced using Reductacryl® [24], following which they were employed to facilitate the self-assembly of polypeptide molecules on GNRs at 4°C. A red-shift of approximately 20 nm (from 800 to 820 nm) was observed in the maximal absorbance peak, which indicated the formation of CnELP–GNR nanoassemblies (Supplementary Figure 1) [23].

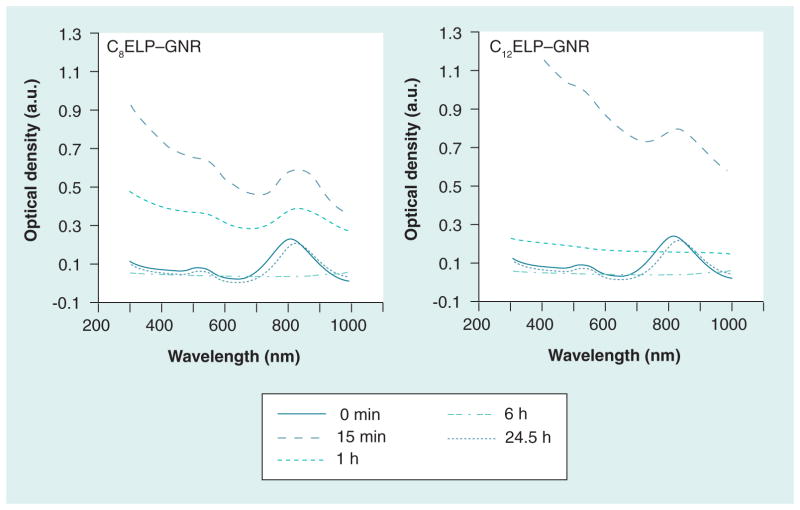

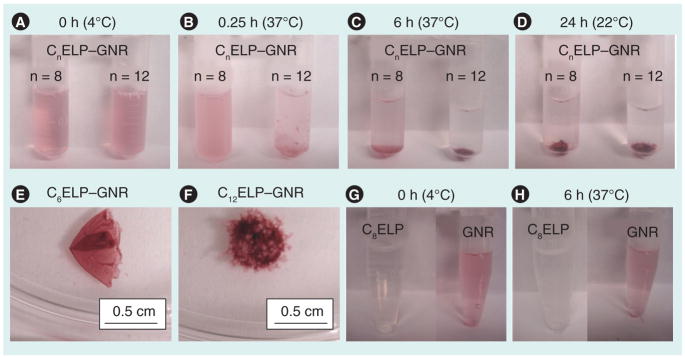

The temperature transition property of CnELPs was exploited for generating C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices from CnELP–GNR nanoassemblies. C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR nanoassemblies were kept at 37°C (> Tt for both ELPs) for 6 h. Incubating GNRs and CnELPs below the transition temperature results in the formation of well-dispersed ‘assemblies’. However, incubation at temperatures above Tt results in temperature-triggered, entropy-dominated phase transition of ELP [27,28], in addition to GNR-thiol (from ELP cysteines), and intra-and inter-molecular cysteine–cysteine crosslinking resulting in the formation of reddish-colored plasmonic matrices (Figure 1A–1F). Lowering the temperature below Tt did not result in dissolution of the C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices (Figure 1D), which indicated that matrix formation was not reversible with temperature, owing to extensive crosslinking. Unlike CnELP–GNR matrices, CnELP in the absence of GNRs (Figure 1G) demonstrated a reversible phase transition process (change in optical density), but no matrix formation. GNRs, in the absence of CnELP, showed no visible differences following the temperature changes (Figure 1H). Kinetics of matrix formation were followed using the light absorption spectrum of the CnELP–GNR supernatant. Matrix formation was not observed immediately after taking the GNR-C8ELP and GNR-C12ELP nanoassemblies out of the 4°C cooler; the light absorption spectrum at time = 0 min in Figure 2 shows a profile characteristic of the GNRs in the dispersion (e.g., Supplementary Figure 1). The maximum optical density was 0.25 for both C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR dispersions under these conditions. Incubation of the C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR assemblies at 37°C first resulted in an increase in optical density indicating aggregation of the GNR-CnELP nanoassemblies above the Tt of the respective CnELPs; the optical densities of C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR assemblies were highest 15 min after incubation. Further incubation led to crosslinking and phase separation of the C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices, leading to precipitation of the solid-phase matrix. Precipitation from the liquid dispersion resulted in the sequestration of both GNRs and the ELP in the solid phase matrix. This, in turn, is manifested as a decrease in optical density or absorbance of the supernatant (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Formation of C8 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod and C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

C8ELP–GNR, C12ELP–GNR, C8ELP alone and GNR alone were incubated in a water bath (37°C) for 6 h, followed by cooling and storage at room temperature. The transition temperature of C8ELP was 31.3°C and that of C12ELP was 30.5°C. Digital snapshots of C8ELP–GNR, and C12ELP–GNR formation were taken at (A) 0 min, (B) 15 min (0.25 h), (C) 6 h and (D) 24 h. Images (E) and (F) show the C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices. Two controls, C8ELP alone and GNR alone, are shown in (G) 0 min and (H) 6 h; no matrices were formed in these cases; as expected, an increase in C8ELP turbidity was observed following an increase in temperature (H).

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Figure 2. Formation and dissolution kinetics of C8 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod and C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

The UV-vis absorbance spectra of the supernatant of C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR were monitored during the 37°C water bath incubation stage (0–6 h), cooling/storage (6–24 h), and 30 min after adding dithiothreitol solution (24.5 h). Increase in optical density of GNR spectrum in the first hour indicates turbidity due to ELP aggregation above the transition temperature. The flat absorbance spectrum at 6 h indicates completion of the matrix formation and the absence of GNRs in the supernatant. Full recovery of the GNR spectrum at 24.5 h indicates degradability of the matrix in the presence of reducing agents.

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

As may be expected, matrix formation using C12ELP–GNR assemblies proceeded at a faster rate compared with that observed with C8ELP–GNR assemblies. This is presumably due to the higher number of thiols/cysteines in the C12ELP sequence, which results in faster crosslinking and, therefore, matrix formation. The absorbance spectrum of the supernatant following incubation at 37°C for 6 h and storage at room temperature for 18 h showed no absorbance signal, which indicated that GNRs were fully sequestered into the matrix and undetectable amounts were present in the supernatant. It was found that 3 h were sufficient for matrix formation in case of C12ELP.

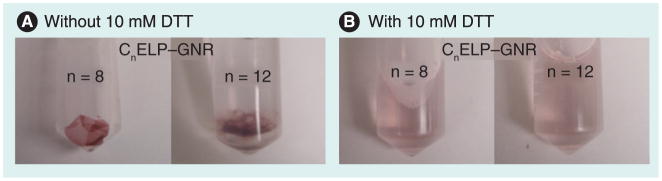

Reduction of disulfide bonds and dissociation of gold-thiol bonds using dithiothreitol led to the degradation of the matrices within minutes (Supplementary Movie 1). DTT is not present in vivo and was used only as a model reducing agent in these experiments in order to demonstrate that the matrices can be degraded under such conditions. While C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices were stable in the absence of DTT, they completely degraded upon addition of the reducing agent (Figure 3). The absorbance spectra indicated complete recovery of the GNRs in the dispersion, as evidenced by the recovery of the transverse and longitudinal peaks at 520 and 840 nm, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Digital snapshots of C8 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod and C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices in the presence and absence of dithiothreitol.

C8ELP–GNR, C12ELP–GNR matrices were formed by incubation at 37°C for 6 h as described above, followed by cooling and storage at room temperature (6–24 h). The supernatant was replaced with an equal volume of 10 mM DTT for 30 min at 4°C (24–24.5 h). (A & B) C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices with (A) and without (B) the presence of DTT.

DTT: Dithiothreitol; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

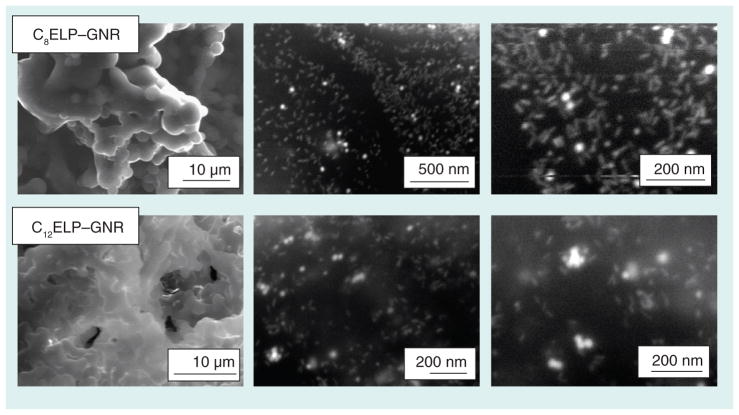

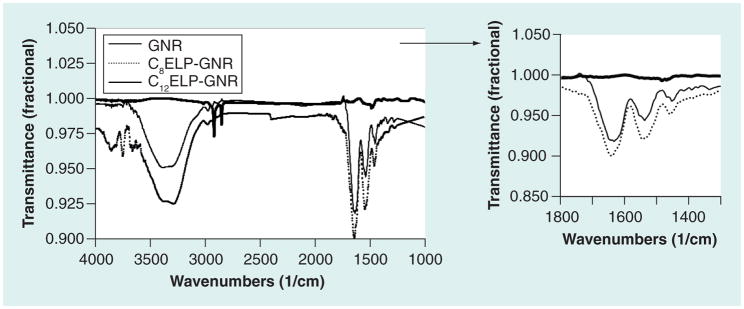

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR nano-composites indicated a combination of N–H bending and C–N stretching vibrations (amide II peak) at wave number 1550 cm−1, a peak corresponding to the C=O stretches in the amide functionality (amide I peak) at 1645 cm−1, and a band corresponding to the N–H stretching vibrations, at 3200 and 3000 cm−1 (Figure 4), which are characteristic of ELP spectra [29]. Field emission SEM images showed that GNRs (~50 nm in length) were well dispersed in the matrices (Figure 5), indicating the possibility that the matrices were able to demonstrate stable plasmonic/photothermal properties. The absorbance spectrum of the C12ELP–GNR matrix (Figure 6) showed the transverse (520 nm) and red-shifted longitudinal peak (850 nm) characteristic of GNRs, indicating that the matrices indeed demonstrated plasmonic properties due to the uniform distribution of the GNRs. Photothermal properties of CnELP–GNR matrices were investigated by recording the temperature of PBS supernatant (500 μl) above the matrix in 24-well plates. Temperatures in each case reached their respective steady-state values (~46°C) 5 min following laser irradiation, consistent with our previous observations with GNRs [23,30,31]; the steady-state temperatures did not change following the relatively minor change in power density from 20 to 25 W/cm2.

Figure 4. Fourier-transform infrared spectrum of gold nanorod, C8 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod and C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

Fourier-transform infrared (Bruker Vacuum FT-IR IFS 66v/S) spectroscopy of C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices indicating characteristic peaks at wave numbers of 3500–3000 cm−1, corresponding to the N–H stretching vibrations, 1660 cm−1, corresponding to the C=O stretches in the amide functionality (amide I peak), and a peak at 1550 cm−1, which is the combination band of N–H bending and C–N stretching vibrations (amide II peak). Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide–GNR shows peaks at 2850 and 2917 cm−1, which reflect the symmetric and asymmetric C–H stretching vibrations, respectively. No peaks were observed in the 2550–2600 cm−1 region, which indicates the absence of the S–H bond.

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Figure 5. Scanning electron microscope images of C8 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod and C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

Environmental field-emission scanning electron microscopy (Philips FEI XL-30 scanning electron microscope operating an accelerating voltage of 25 kV) images indicate a fairly uniform distribution of GNRs throughout C8ELP–GNR and C12ELP–GNR matrices.

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Figure 6. Optical and photothermal response of C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

C12ELP–GNR matrices were formed on a glass cover slip (inset) and the absorbance (optical density) spectrum of the film was analyzed using a plate reader. Uniform distribution of GNRs in the matrix resulted in optical properties similar to that of GNR dispersions; characteristic peaks at 520 nm and in the near infrared (~850 nm) region in the spectrum can be seen. Retention of optical properties of GNRs in the matrix resulted in a reliable photothermal response as seen from the temperature kinetics of 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline on top of the matrix in a 24-well plate. The matrix was irradiated using an 850 nm laser at two different power densities and the temperature of phosphate-buffered saline was measured using a K-type thermocouple.

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

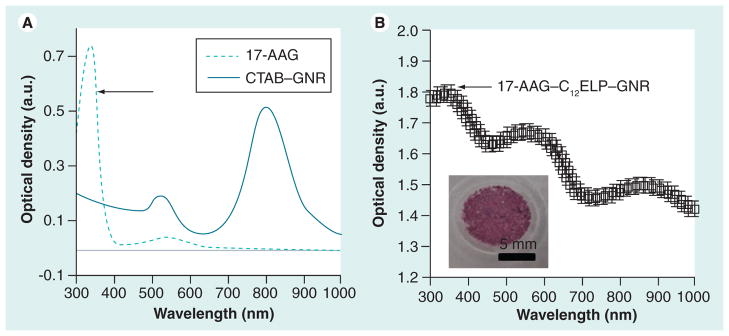

Suboptimal administration of hyperthermia can result in the incomplete ablation of tumors and selection of clones that are resistant to treatment. While temperatures above 46°C result in significant loss of cell viability, mild or moderate hyperthermic temperatures (40–46°C) can have differential cytotoxic effects on cells, leading to variable efficacies. Constitutive and induced expression of HSPs, including HSP90, results in the refolding of proteins denatured by hyperthermia and, therefore, results in overcoming the apoptotic effects of the treatment. In particular, HSP90 is a stress-related protein, which interacts with several client proteins and regulates key processes inside cells, including protein degradation, and aids cancer cell survival following hyperthermia. Strategies that combine hyperthermic ablation with chemotherapeutic drugs that can overcome HSP-induced resistance can result in enhanced efficacy of hyperthermia as an adjuvant treatment. As a representative example of this approach, we incorporated the chemotherapeutic HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG in the matrix, with an eye towards generating a multifunctional matrix capable of simultaneously administering both hyperthermia and chemotherapy, in order to enhance the ablation of cancer cells. The HSP90 inhibitor was incorporated within C12ELP–GNR matrices during their formation leading to 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices (Figure 7). The absorbance spectrum of 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices demonstrated an additional peak at 335 nm (Figure 7), which was indicative of the incorporation of 17-AAG within the polypeptide matrix; approximately 550 μg of the drug were incorporated within a single matrix.

Figure 7. Spectrum of 17-AAG-loaded C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

C12ELP–GNR matrices loaded with the heat-shock protein (HSP) 90 inhibitor drug, 17-AAG for ablation of cancer cells using a combination treatment of hyperthermia and HSP inhibition.

(A) Absorbance spectrum 17-AAG shows a peak at approximately 330 nm, which is reflected in the 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices. (B) The inset in (B) shows a digital snapshot of the 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrix loaded with 0.55 mg of the HSP90 inhibitor drug. Drug loading can also be seen from the change in color of the matrix.

CTAB: Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

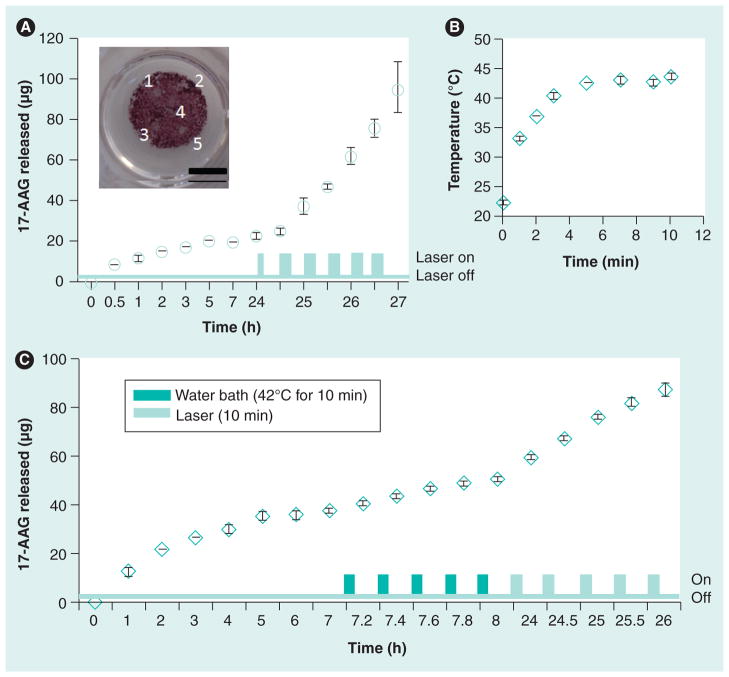

Figure 8 shows a representative release profile of the 17-AAG from the matrix. The matrix was first placed in PBS to investigate diffusional leaching of the drug. Approximately 10 μg of the drug was released in the first hour, following which an additional 7 μg of the drug were released over the next 23 h, indicating that only a total of 3% of the encapsulated drug leached out due to diffusion. This demonstrates that the matrices are able to stably incorporate chemotherapeutic drugs with minimal loss owing to leaching. This is significant, since unintended drug loss from the matrix can result in undesired side effects. Subjecting the matrix to laser irradiation resulted in an increase in local temperature due to the photothermal effects of GNRs, which, in turn, led to enhanced release of 17-AAG from the matrix, presumably due to ELP structural changes and aggregation above the transition temperature, which in turn, can result in contraction of the matrix leading to drug efflux. The concomitant temperature increase is shown in Figure 8 and is similar to that observed with the matrix in the absence of the drug (Figure 6). A 5-min laser irradiation pulse (850 nm laser, 25 W/cm2) resulted in the release of only 2.5 μg 17-AAG, indicating longer exposure times were necessary for increased release of the drug. Subsequent laser exposures were, therefore, carried out for 10 min each (850 nm, 25 W/cm2), which resulted in the release of 12.6 μg ± 2.4 μg for each round of laser irradiation. Discolored spots on the C12ELP–GNR matrix (Figure 8) indicate regions of drug release following exposure to the laser. This is consistent with the temperature profiles in Figure 8, which indicated that merely reaching hyperthermic temperatures may not be enough to trigger drug release and that sustained hyperthermic temperatures are required.

Figure 8. Photothermally activated release of the heat-shock protein 90 inhibitor drug, 17-AAG from 17-AAG–C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

(A) Diffusional release (leaching) of 17-AAG from the 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrix was monitored for 24 h to a supernatant of phosphate-buffered saline (volume 500 μl). Approximately 10 μg of the drug was released in the first hour, following which minimal drug release was observed for the rest of the duration as seen in the cumulative data plotted above. The matrix was then subjected to laser irradiation for releasing the drug. During laser pulse-triggered release, the first laser irradiation lasted for 5 min (850 nm, 25 W/cm2), the second to sixth laser irradiations (850 nm, 25 W/cm2) were for 10 min, with 20-min interval without laser in between each irradiation. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation from four independent experiments (n = 4). (B) The temperature profile during 10-min laser exposure was monitored with a K-type thermocouple. The temperature reached 43–44°C (heat-shock conditions) following 5 min of laser irradiation, and remained invariant thereafter. Laser irradiation resulted in an additional 45–50 mg of 17-AAG released from the 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices, indicating the potential for combined hyperthermia and heat-shock inhibition. (C) Role of laser irradiation on enhancing 17-AAG release from C12ELP–GNR matrices. Matrices were first investigated for diffusional leaching of the drug, followed by incubation in a water bath at 42°C, and were finally irradiated with an near-infrared laser. Increased amounts of drug were released following laser treatment, presumably due to higher localized temperatures in the path of the laser.

17-AAG: 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod; HSP: Heat-shock protein.

In order to further investigate the role of laser-induced drug release, we first investigated the matrix for diffusional drug release, followed by incubation at moderately hyperthermic temperatures (42°C), and finally laser treatments. The total amount of drug originally encapsulated in this matrix was approximately 614 μg, which was higher than the amount encapsulated in the matrix shown in Figure 8. As seen in Figure 8, higher 17-AAG quantities were released following laser irradiation compared with the water bath incubation treatment. It is possible that temperatures directly in the path of the laser are significantly higher than 42–44°C, and lead to greater drug release due to more significant changes in the matrix at these locations. This is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Taken together, these results indicate that the photothermal properties of the polypeptide matrix facilitate local increases in temperature following laser irradiation, which in turn triggers release of the encapsulated drug, presumably due to a combination of increased drug diffusivity and ELP aggregation and contraction at temperatures above the polypeptide transition temperature.

We next evaluated the efficacy of the simultaneous administration of hyperthermia and HSP90 inhibitor for the ablation of prostate cancer cells. In order to account for the efficacy of this combination treatment, two ‘single-agent’ treatments were first carried out: hyperthermia alone, in which the matrix without the 17-AAG drug was employed for killing cancer cells only due to hyperthermic temperatures in the absence of the drug, and 17-AAG alone, in which loss of cancer cell viability due to constitutive 17-AAG diffusional release from the matrix was evaluated in the absence of laser-induced hyperthermia.

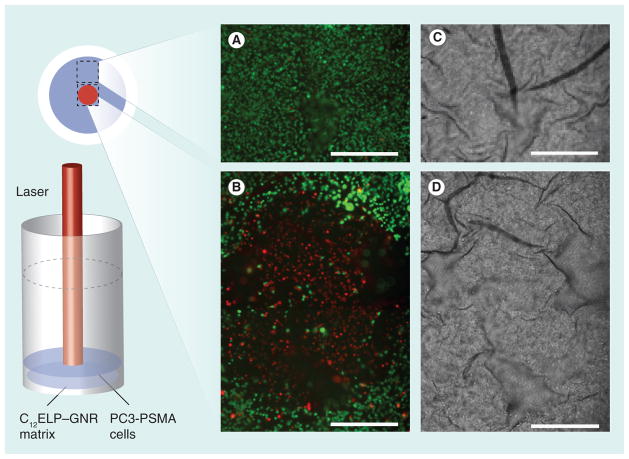

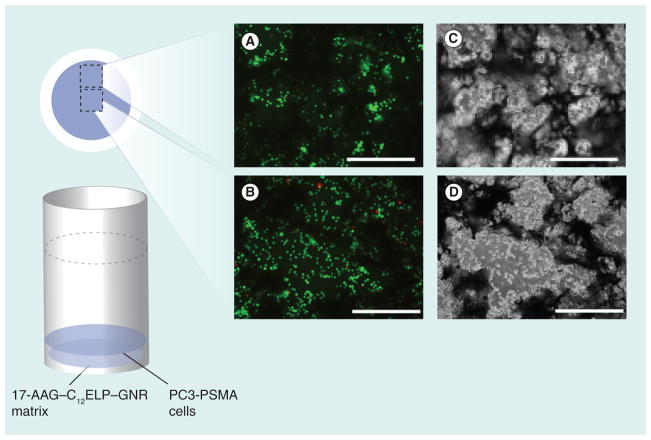

C12ELP–GNR matrices (without 17-AAG) supported the growth of PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cells, indicating that the plasmonic matrix was not toxic to cells. For the ‘hyperthermia alone’ treatment, cells were irradiated with an 850 nm laser (25 W/cm2 laser for 7 min) and cell viability was determined using the Live/Dead assay 24 h after the laser treatment. Phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy images were recorded immediately after staining. As expected, laser irradiation resulted in significant death of PC3-PSMA cells directly in the path of the laser beam as seen from the red-stained cells in Figure 9, consistent with previous observations in the literature [32,33]. However, cells outside the path of the laser beam did not undergo any loss of viability as seen from the green-stained living cells in Figure 9. These results highlight spatial limitations associated with nanoparticle-mediated hyperthermic ablation of cancer cells; while nanoparticles and laser irradiation can be employed for localized treatments, effective treatment can be administered only over a limited region, leading to ineffective treatment. Importantly, the plasmonic matrix is biocompatible and can be used for the hyperthermic ablation of cancer cells, and in treatments where the spatial limitations of hyperthermia are not a concern.

Figure 9. C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices cell ablation set up with fluorescence (A & B) and phase (C & D) images.

PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cells were cultured on C12ELP–GNR matrices (without 17-AAG drug) for 24 h, and irradiated with an 850-nm laser (25 W/cm2) for 7 min. Viability of cells directly under the 1-mm laser irradiation spot (top; circled area) and outside the laser spot (bottom) was determined using the Live/Dead® assay in which living cells stained green while dead cells stained red. Cells directly under the laser were killed by the hyperthermic treatment while those outside the laser irradiation spot were alive. Approximate locations of the images on the matrix are shown. Representative images are from two independent experiments (n = 2). Scale bar: 500 μm.

ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

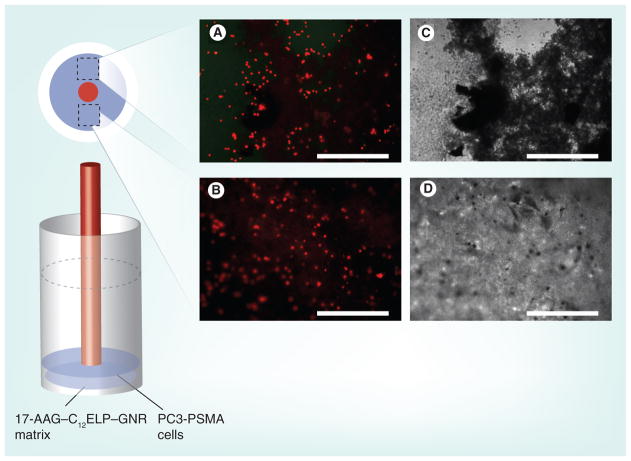

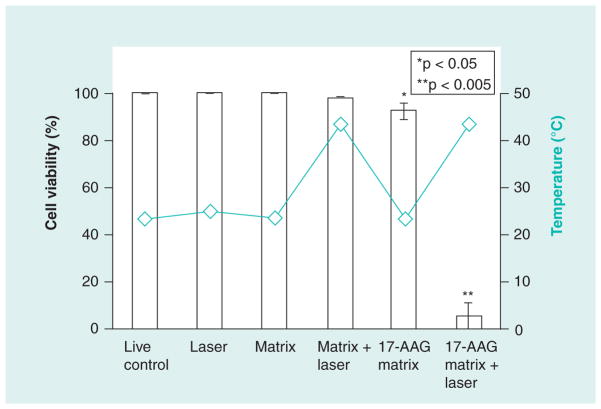

C12ELP–GNR plasmonic matrices, containing the anti-HSP90 drug 17-AAG (17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR), were evaluated in the absence of laser-induced hyperthermia (drug-alone treatment). The matrices were able to support cell culture for 48 h, indicating that the constitutive diffusional release of 17-AAG from the matrix was not sufficient to induce cell death in cancer cells (Figure 10). In order to investigate the efficacy of the combination treatment for killing cancer cells, PC3-PSMA cells were exposed to an 850-nm laser (25 W/cm2 laser for 7 min) and as before, cell viability was evaluated 24 h following the laser treatment. While a single circular shape corresponding to the size of the laser beam could not be located in this case, dead cells could be seen throughout the matrix (Figure 11), indicating that a combination of the hyperthermic temperatures and the triggered release of the anti-HSP90 drug 17-AAG was responsible for extensive cancer cell death. The synergistic action between these combination treatments is demonstrated by quantitative analysis of the cell death results (Figure 12). Drug-alone and laser-alone treatments resulted in minimal loss of cell viability (<10% of the cell population). However, the combination treatment (laser-induced hyperthermia and release of the HSP90 inhibitor) resulted in over 90% loss in cell viability (Figure 12). Our results indicate that drug-loaded nanoparticle–polypeptide matrices can simultaneously overcome cancer cell resistance to nanoparticle-induced hyperthermia, which is mediated by HSP overexpression, and spatial limitations of laser-induced hyperthermia using plasmonic nanoparticles (Table 1).

Figure 10. 17-AAG–C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices cell culture set up with fluorescence (A & B) and phase (C & D) images.

PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cells were cultured on 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR matrices for 48 h (no laser treatment) and viability of cells was determined using the Live/Dead® assay. Diffusional release of 17-AAG from the matrix did not alter the viability of the cells. Approximate locations of the images on the matrix are shown. Representative images from three independent experiments (n = 3). Scale bar: 500 μm.

17-AAG: 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Figure 11. 17-AAG–C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices cell ablation set up with fluorescence (A & B) and phase (C & D) images.

PC3-PSMA human prostate cancer cells were cultured on C12ELP–GNR-17-AAG matrices for 24 h and irradiated with an 850-nm laser (25 W/cm2) for 7 min. Cell viability was investigated after 24 h of the laser treatment using the Live/Dead® assay (total cell culture time = 48 h). Representative images at two different locations away from the laser irradiation spot demonstrate approximately 90% cell death due to the combination of mild hyperthermia (43°C; Figure 8B) and release of the heat-shock inhibitor drug 17-AAG (Figure 8A). This pattern of uniform cell death throughout the well is higher than what was seen with the single agent (i.e., mild hyperthermia alone and 17-AAG release alone) treatments. Approximate locations of the images are on the matrix are shown. Representative images from three independent experiments (n = 3). Scale bar: 500 μm.

17-AAG: 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Figure 12. Quantitative analysis of cell death demonstrates the efficacy of the laser-induced combination treatment of hyperthermia and heat-shock inhibitor 17-AAG using 17-AAG–C12 elastin-like polypeptide–gold nanorod matrices.

Matrix indicates the C12ELP–GNR matrix and 17-AAG matrix indicates 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR (i.e., drug-loaded) matrices (n = 3 for all conditions).

17-AAG: 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Table 1.

Summary of combination treatments.

| CnELP–GNR matrices | Laser power density (7-min irradiation) | Cell death | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser spot | Periphery | ||

| C12ELP–GNR | 0 W/cm2 | No | No |

| C12ELP–GNR | 25 W/cm2 | Yes | No |

| 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR | 0 W/cm2 | No | No |

| 17-AAG–C12ELP–GNR | 25 W/cm2 | Yes | Yes |

17-AAG: 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin; ELP: Elastin-like polypeptide; GNR: Gold nanorod.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that engineered polypeptides can be interfaced with GNRs, resulting in the formation of stable, degradable and biocompatible plasmonic matrices. The matrices maintain the photothermal properties of the GNRs and can be employed for the hyperthermic ablation of cancer cells. However, spatial limitations of the administered hyperthermia treatment, in addition to the prosurvival heat-shock response associated with cancer cells, led us to incorporate the HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG in the matrix. Laser irradiation of the plasmonic matrices resulted in simultaneous administration of hyperthermic temperatures and release of 17-AAG. Synergistic action between hyperthermia and HSP90 inhibition led to significant enhancement of cancer cell death. To our knowledge, this is the first report that describes the use of a HSP inhibitor in combination with nanoparticle-induced hyperthermia for the ablation of cancer cells. Our results indicate that such matrices can be used for enhancing the efficacy of hyperthermia as an adjuvant treatment. In addition, this is the first report that describes ELP–GNR matrices as plasmonic nanobiomaterials. The availability of a variety of engineered polypeptides, nanoparticles and chemotherapeutic drugs should advance this approach, leading to biocompatible plasmonic matrices for different therapeutic modalities and other biomedical applications, including biosensing and regenerative medicine.

Future perspective

It is anticipated that plasmonic matrices will be useful for localized delivery of drugs for a variety of applications, in which on-demand release of drugs can be affected using near-infrared irradiation. Owing to their size and the limited penetration of near-infrared radiation in the body, these matrices may find application in the elimination of accessible, superficial tumors where intratumoral injection is possible, or for destruction of residual disease after surgery. In addition, these matrices may be useful in other superficial/topical applications, including antibacterial materials and wound healing. These matrices could also be useful in regenerative medicine for combined cell and drug delivery and in biosensing applications. Future work in our laboratory will involve an investigation into these applications of the plasmonic matrices. In addition, detailed studies on the effect of ELP and GNR concentration on matrix formation, phase behavior and kinetics of matrix formation will also be carried out.

Supplementary Material

Executive summary.

Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) containing 8 and 12 cysteines within the polypeptide repeat sequence were self-assembled with gold nanorods (GNRs) leading to the formation of GNR–ELP matrices.

GNR–ELP matrices demonstrate a robust photothermal response due to the homogeneous distribution of GNRs throughout the polypeptide matrix.

Laser irradiation of the matrix results in death of cancer cells directly under the path of the laser, indicating that the photothermal properties of the matrix can be used for administering hyperthermia to cancer cells. These results also demonstrate the spatial limitations of nanoparticle-induced hyperthermia.

GNR–ELP matrices alone were not toxic to cells employed in this study.

Chemotherapeutic drugs can be incorporated in the GNR–ELP matrices.

Minimal diffusional leaching of the encapsulated drug (17-[allylamino]-17-demethoxygeldanamycin [17-AAG]) was observed from the matrices. The concentrations of the drug released from the matrix were insufficient to induce cancer cell death.

Laser irradiation of drug-containing GNR–ELP matrices results in release of large quantities of the encapsulated drug.

Laser irradiation resulted in simultaneous administration of hyperthermia and release of the heat-shock protein 90 inhibitor 17-AAG, which resulted in significant (>90%) death of prostate cancer cells compared with single-agent treatments (i.e., hyperthermia alone and 17-AAG alone, both of which resulted in <10% cell death).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zaki Megeed and Martin L Yarmush at the Center for Engineering in Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, MA, for helpful discussions. The authors also thank Su Lin and Neal Woodbury at the Biodesign Institute at ASU for access to the laser facility.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact: reprints@futuremedicine.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CBET 0829128), NIH (5R21 CA 133618-02) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA 1-10-1-019), as well as start-up funds from the state of Arizona to Kaushal Rege, and a Fulton Undergraduate Research Initiative (FURI) Award at ASU to Alisha Nanda. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Bibliography

- 1.Overgaard J. The current and potential role of hyperthermia in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16(3):535–549. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang XH, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Determination of the minimum temperature required for selective photothermal destruction of cancer cells with the use of immunotargeted gold nanoparticles. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82(2):412–417. doi: 10.1562/2005-12-14-RA-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He XM, Wolkers WF, Crowe JH, Swanlund DJ, Bischof JC. In situ thermal denaturation of proteins in dunning at-1 prostate cancer cells: implication for hyperthermic cell injury. Ann Biomed Engin. 2004;32(10):1384–1398. doi: 10.1114/b:abme.0000042226.97347.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lepock JR. Cellular effects of hyperthermia: relevance to the minimum dose for thermal damage. Int J Hypertherm. 2003;19(3):252–266. doi: 10.1080/0265673031000065042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki T, Wakabayashi M, Nakagawa T, et al. Percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy for solitary metastatic liver tumors from colorectal cancer: a pilot clinical study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(2):322–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazelle GS, Goldberg SN, Solbiati L, Livraghi T. Tumor ablation with radio-frequency energy. Radiology. 2000;217(3):633–646. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc26633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilger I, Andra W, Bahring R, Daum A, Hergt R, Kaiser WA. Evaluation of temperature increase with different amounts of magnetite in liver tissue samples. Investig Radiol. 1997;32(11):705–712. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jolesz FA, Hynynen K. Magnetic resonance image-guided focused ultrasound surgery. Cancer J. 2002;8:S100–S112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickerson EB, Dreaden EC, Huang X, et al. Gold nanorod assisted near-infrared plasmonic photothermal therapy (PPTT) of squamous cell carcinoma in mice. Cancer Lett. 2008;269(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Near-infrared resonant nanoshells for combined optical imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2007;7(7):1929–1934. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skrabalak SE, Chen J, Sun Y, et al. Gold nanocages: synthesis, properties, and applications. Accounts Chem Res. 2008;41(12):1587–1595. doi: 10.1021/ar800018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang X, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Plasmonic photothermal therapy (PPTT) using gold nanoparticles. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23(3):217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10103-007-0470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(6):2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Maltzahn G, Park JH, Agrawal A, et al. Computationally guided photothermal tumor therapy using long-circulating gold nanorod antennas. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3892–3900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma LL, Feldman MD, Tam JM, et al. Small multifunctional nanoclusters (nanoroses) for targeted cellular imaging and therapy. ACS Nano. 2009;3(9):2686–2696. doi: 10.1021/nn900440e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong L, Wei Q, Wei A, Cheng J-X. Gold nanorods as contrast agents for biological imaging: optical properties, surface conjugation and photothermal effects. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85(1):21–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepock JR. Cellular effects of hyperthermia: Relevance to the minimum dose for thermal damage. Int J Hypertherm. 2003;19(3):252–266. doi: 10.1080/0265673031000065042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbons NB, Watson RW, Coffey RN, Brady HP, Fitzpatrick JM. Heat-shock proteins inhibit induction of prostate cancer cell apoptosis. Prostate. 2000;45(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000915)45:1<58::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rylander MN, Feng Y, Bass J, Diller KR. Thermally induced injury and heat-shock protein expression in cells and tissues. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1066:222–242. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heath EI, Hillman DW, Vaishampayan U, et al. A Phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(23):7940–7946. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solit DB, Osman I, Polsky D, et al. Phase II trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8302–8307. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikoobakht B, El-Sayed MA. Preparation and growth mechanism of gold nanorods (NRs) using seed-mediated growth method. Chem Mater. 2003;15(10):1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H-C, Koria P, Parker SM, Selby L, Megeed Z, Rege K. Optically responsive gold nanorod–polypeptide assemblies. Langmuir. 2008;24(24):14139–14144. doi: 10.1021/la802842k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rege K, Patel SJ, Megeed Z, Yarmush ML. Amphipathic peptide-based fusion peptides and immunoconjugates for the targeted ablation of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(13):6368–6375. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barua S, Joshi A, Banerjee A, et al. Parallel synthesis and screening of polymers for nonviral gene delivery. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(1):86–97. doi: 10.1021/mp800151j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong MC, Latouche JB, Krause A, Heston WD, Bander NH, Sadelain M. Cancer patient T cells genetically targeted to prostate-specific membrane antigen specifically lyse prostate cancer cells and release cytokines in response to prostate-specific membrane antigen. Neoplasia. 1999;1(2):123–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urry DW. Physical chemistry of biological free energy transduction as demonstrated by elastic protein-based polymers. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101(51):11007–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(2):357–367. doi: 10.1021/bm015630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janorkar AV, Rajagopalan P, Yarmush ML, Megeed Z. The use of elastin-like polypeptide–polyelectrolyte complexes to control hepatocyte morphology and function in vitro. Biomaterials. 2008;29(6):625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H-C, Barua S, Kay DB, Rege K. Simultaneous enhancement of photothermal stability and gene delivery efficacy of gold nanorods using polyelectrolytes. ACS Nano. 2009;3(10):2941–2952. doi: 10.1021/nn900947a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Hc, Rege K, Heys JJ. Spatiotemporal temperature distribution and cancer cell death in response to extracellular hyperthermia induced by gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2009;4(5):2892–2900. doi: 10.1021/nn901884d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(6):2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowery AR, Gobin AM, Day ES, Halas NJ, West JL. Immunonanoshells for targeted photothermal ablation of tumor cells. Int J Nanomed. 2006;1(2):149–154. doi: 10.2147/nano.2006.1.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.