Abstract

Aptamers are molecules identified from large combinatorial nucleic acid libraries by their high affinity to target molecules. Due to a variety of desired properties, aptamers are attractive alternatives to antibodies in molecular biology and medical applications. Aptamers are identified through an iterative selection–amplification process known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX). Although SELEX is typically carried out using purified target molecules, whole live cells are also employable as selection targets. This technology, Cell-SELEX, has several advantages. For example, generated aptamers are functional with a native conformation of the target molecule on live cells, and thus, cell surface transmembrane proteins would be targets even when their purifications in native conformations are difficult. In addition, cell-specific aptamers can be obtained without any knowledge about cell surface molecules on the target cells. Here, I review the progress of Cell-SELEX technology and discuss advantages of the technology.

Key words: biomarkers, cancer research, nucleic acids, stem cells

Introduction

Aptamers are molecules identified from large combinatorial nucleic acid libraries by their high affinity to target molecules.1,2 Similar to antibodies, aptamers have high affinity and specificity to target molecules. There are, however, several unique qualities of aptamers that are of additional benefit, including robustness against both reducing conditions and heat denaturation. Typical aptamers are shorter than 40 nucleotides (nts) and easy for the high-quality production by chemical synthesis. In addition, they can be inactivated under physiological conditions by hybridization with antisense oligonucleotides, and thus, design of an antidote molecule is quite straightforward. Therefore, the application of aptamers in molecular biology and medical science has been extensively explored.1,2

Aptamers are identified through an iterative selection–amplification process known as systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX).3,4 During the process, a single-stranded nucleic acid (DNA, RNA, or modified nucleic acids) pool consisting of 1014–1015 variants of a random 30–100-nt sequence is incubated with a target molecule. Then, variants with the desired binding activity are recovered, followed by amplification of the enriched library by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Employing this enriched PCR product, the single-stranded pool is regenerated by template-strand removal or by in vitro transcription (for DNA or RNA pools, respectively). Typically, this process is repeated for several to more than 20 rounds for the identification of aptamers.

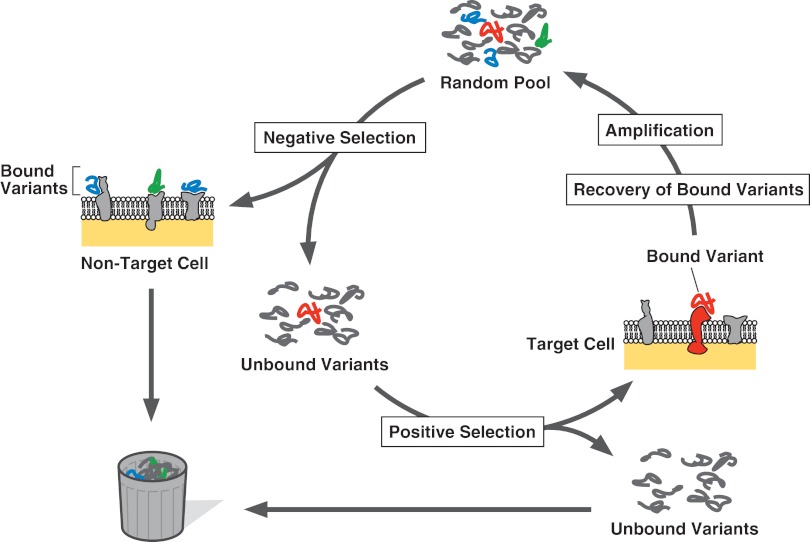

Since the establishment of the SELEX procedure in 1990,3,4 many aptamers have been generated against a variety of targets, including small chemical compounds to large multidomain proteins.1,2 Although SELEX is typically performed using a highly purified target molecule, a theoretical study has suggested that complex heterogeneous targets are also employable for the generation of specific aptamers.5 This idea has been experimentally confirmed by the identification of aptamers against red blood cell ghosts,6 followed by the identification against live African trypanosomes.7 Combining with a negative selection step by which variants binding to nontarget cells are eliminated, target cell-specific aptamers can be generated (Fig. 1). Because of several attractive features of SELEX using live cells, or Cell-SELEX, varieties of live cells have been examined as targets for the procedure (Table 1).7–23 In this article, I review the procedural progress of Cell-SELEX technology.

FIG. 1.

Cell systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) with a negative selection step. By a negative selection step, unspecific and nontarget cell-specific variants (shown by blue and green, respectively), are eliminated from the pool. Then, the intended aptamer (red) that specifically binds to the target cells is selected by a positive selection step, followed by pool regeneration.

Table 1.

Aptamers Identified Via Cell-SELEX

| Target cells | Pool construction | Selection procedures | Results | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma brucei | RNA | Positive selection against the live, bloodstream stage trypanosomes. | One aptamer recognized a subunit of a transferrin receptor (ESAG), and the bound aptamer rapidly become internalized. | 7,10 |

| T. brucei | 2′-fPy-RNA | Purified proteins of two VSG variants or cells expressing them were alternatively employed as selection targets. | An aptamer binding to broad varieties of VSG variants was identified. | 8 |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | 2′-fPy-RNA | Elution of variants bound to the cells by the addition of excess amount of the matrix molecule. Negative selection using a noninfective stage of the parasite. | Aptamers inhibiting the parasite invasion were identified. | 9 |

| Human T-cell lymphoma line (CCRF-CEM) | DNA | Negative selection using human B-cell lymphoma line (Ramos). | Several aptamers specifically binding to the target cells were identified, and each aptamer might recognize a cell surface molecule different from the targets of the other aptamers. | 11 |

| Mouse ESCs (CCE) | 2′-fPy-RNA | Positive selection in the presence of excess amount of a competitor aptamer against the same target cells. Negative selection using a differentiated cell line (A-9). | Differentiation process of mouse ESCs could be monitored employing the fluorescently labeled aptamers. | 12 |

| Vaccina virus-infected, adenocarcinomic epithelial cells (A549) | DNA | Negative selection using uninfected A549 cells. | The identified aptamers bound to several cell lines infected by the virus and would recognize the viral proteins displayed on the host cell surface. | 13 |

| Rat endothelial cells (YPEN-1) | DNA | Negative selection using mouse microglial cells (N9). | One aptamer recognized a protein overexpressed in the tumor microvessels (pigpen). | 14 |

| Immature or mature DCs | DNA | Negative selection using mature or immature DCs for the selection against immature or mature DCs, respectively. | The enriched aptamer pools were employed for affinity isolation of the target cell-specific markers, and several novel markers were identified. | 15 |

| PC12 cells ectopically expressing receptor tyrosine kinase RET | 2′-fPy-RNA | Negative selection using parental PC12 cells. | An antagonistic aptamer binding to cell surface RET was identified. | 16,17 |

| CHO cells ectopically expressing TbRIII | 2′-fPy-RNA | Negative selection using parental CHO cells. | An antagonistic aptamer binding to cell surface TbRIII was identified. | 18,19 |

| Vital CD19+ Burkitt lymphoma cells | DNA | Positive selection was performed by using FACS. | Ten rounds of FACS-SELEX identified intended aptamers, whereas 20 rounds of canonical SELEX based on centrifugation did not. | 20 |

| Human chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells | DNA | Selection based on intracellular uptake rather than binding. | Identified DNA motifs efficiently become transported into the cells. | 21,22 |

| Hepatic tumor-implanted mice | 2′-fPy-RNA | Selection of tumor-targeting aptamers under in vivo context. | One aptamer localized exclusively to the intrahepatic tumors when intravenously injected into the mice. The aptamer recognized an RNA halicase (p68). | 23 |

SELEX, systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment; VSG, variable surface glycoprotein; DC, dendritic cells; TbRIII, transforming growth factor-beta receptor type III; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; ESC, embryonic stem cell; 2′-fPy-RNA, 2′-fluoropyrimidine-modified RNA.

SELEX Against Live Pathogenic Organisms

Because aptamers are useful for the development of diagnosis reagents and drugs, varieties of live pathogenic organisms have been utilized as targets for Cell-SELEX.7–9,24–31 As described above, the first example of Cell-SELEX was performed using a live pathogenic organism, African trypanosomes Trypanosoma brucei.7

T. brucei is a unicellular protozoan parasite and has two hosts; its insect vector (like the tsetse fly) and the mammalian host. This parasite causes African sleeping sickness, a chronic disease in humans and Nagana in cattle. A unique, notable feature of T. brucei is its cell surface shield, known as variable surface glycoprotein (VSG). Because T. brucei constantly varies expressing variant of VSG (its genome encodes ∼1000 variants of VSG with polymorphic N-termini), and other invariant surface molecules are embedded in the polymorphic VSG layer, the parasite can escape from the host immune system.

Homann and Goringer carried out SELEX using live, bloodstream stage trypanosomes of T. brucei as a target and identified several RNA aptamers binding to the live parasite with high affinity.7 UV cross linking and fluorescence microscopy analyses suggested that one aptamer (variant 2–16) binds to expression site associated gene 7 (ESAG 7),7 a subunit of a transferrin receptor localizing the flagellar pocket. The flagellar pocket is a flask-shaped invagination of the plasma membrane, and in contrast to antibodies, small size (∼25 kDa) of the aptamer enabled its access to the inside area of the flagellar pocket.

The same group also reported the generation of aptamers binding to broad varieties of VSG variants.8 Starting with a serum-stable, 2′-fluoropyrimidine-modified RNA (2′-fPy-RNA) pool, they initially performed SELEX against the purified protein of one VSG variant, VSG117, followed by SELEX against the live trypanosomes of T. brucei strain stably expressing the same VSG variant. Then, following rounds of SELEX were performed against the purified protein of a different variant, VSG221, followed by against the live parasites. As expected, the resulting aptamer showed affinities to both variants, and importantly, also to live parasites expressing VSG variants not used in the SELEX.

Ulrich et al. generated aptamers using another live parasite, American trypanosomes, Trypanosoma cruzi, by a unique SELEX strategy.9 T. cruzi causes Chagas disease, a potentially fatal disease of humans. It is known that the parasite surface interacts with the host cell–matrix molecules, and this interaction plays an essential role for parasite invasion. The authors aimed to generate aptamers that compete with the matrix molecules for binding to the parasite to inhibit the host cell–parasite interactions. To this end, a 2′-fPy-RNA pool was incubated with live T. cruzi trypanosomes, followed by the specific elution of desired aptamers by the addition of an excess amount of the matrix molecule (i.e., fibronectin, laminin, heparan sulfate, or thrombospondin). Furthermore, a negative selection step using a noninfective stage (the epimastigote stage) of the parasite was included to eliminate undesired aptamers (Fig. 1). The procedure successfully generated aptamers specific for the target parasite, and the intended inhibitory activity of several aptamers was confirmed by the in vitro invasion assay using monkey kidney cells.

SELEX Against Cultured Mammalian Cells

To develop molecular probes in diagnosis and basic research, aptamers recognizing a certain mammalian cell type are promising tools. Cancer cell lines are one of the most extensively examined targets for Cell-SELEX, and until now, many aptamers against varieties of cancer cell types have been generated (reviewed in Refs.32,33). With a fluorescent labeling (like fluorescein and cyanines), these aptamers have shown to be useful as cancer probes.32,33 For example, Shangguan et al. reported the generation of a series of DNA aptamers as molecular probes for cancer study.11 They used human precursor T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (CCRF-CEM) and the human B-cell line from Burkitt's lymphoma (Ramos) for positive and negative selection steps, respectively. The obtained aptamers showed high affinity to target CCRF-CEM cells and not to Ramos cells. The detailed binding analyses were performed using several cancer cells and also CCRF-CEM cells with partial proteinase treatment, and the results suggested that each aptamer recognized a cell surface molecule different from the targets of the other aptamers. Cell-SELEX can be performed without any knowledge about cell surface molecules displayed on the target cells, and the technology enables de novo generation of cell-specific molecular probes.

Cell-SELEX against somatic cells and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) has been also reported.12 Recently, the author's group succeeded in the generation of 2′-fPy-RNA aptamers against mouse ESCs.34 The generated aptamers efficiently bound to the ESCs and hardly to all the examined differentiated cell lines. In addition, the differentiation process of mouse ESCs could be monitored employing the fluorescently labeled aptamers. Because stem cells are essential source for regenerative medicine and basic developmental biology, development of novel molecular probes for stem cells would be precious.

Another interesting example of Cell-SELEX is the generation of DNA aptamers specifically binding to virus-infected cells.13 Through the virus infection, the host cell surface is modified by the insertion of viral proteins, and these alterations provide virus-specific targets for the design of specific molecular probes that can recognize and provide molecular signatures for virus-infected cells. Tang et al. performed Cell-SELEX against vaccina virus-infected, adenocarcinomic epithelial cells (A549).13 Combining with a negative selection step employing uninfected A549 cells, they succeeded in the generation of the infected cell-specific DNA aptamers. The isolated aptamers bound to several cell lines infected by the virus, suggesting that the aptamers recognized the viral proteins displayed on the host cell surface. Similar effort might reveal host cell proteins if their expression levels are changed upon virus infection.

Biomarker Discovery Employing Cell-Binding Aptamers

Because target molecules of the aptamers generated by Cell-SELEX may be previously unrecognized as cell-specific surface molecules, they might be novel biomarkers. Thus, Cell-SELEX can be applied for de novo identification of novel biomarkers for a desired cell. For example, Blank et al. reported Cell-SELEX employing rat endothelial cells (YPEN-1) and mouse microglial cells (N9) for positive and negative selection steps, respectively.14 Many of the generated aptamers bound to the pathological microvasculature of glioblastoma, and one aptamer (variant III.1) displayed the most intensive binding to the vasculature exclusively in areas of solid tumor growth. The target protein of aptamer III.1 was analyzed by mass fingerprinting and peptide sequencing, and identified as pigpen, a regulatory protein of endothelial differentiation overexpressed in the tumor microvessels. It should be noted that the target identification is sometimes very difficult (or even impossible), because it requires enough amount of the purified target molecules, however.

Berezovski et al. have developed more systematic procedure for the identification of novel biomarkers on desired target cells.15 The procedure, termed aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery (AptaBiD), includes three steps: (1) Construction of the enriched aptamer pools against target cells by Cell-SELEX; (2) affinity isolation of biomarker candidates based on the binding activities of the aptamer pools; (3) identification of the isolated candidate proteins by peptide mass fingerprinting. In the procedure, the enriched pools, instead of cloned aptamers, are utilized, and this would enhance opportunities for the biomarker identification without increasing the number of experimental times. The authors constructed DNA aptamer pools against immature and mature dendritic cells (DCs) by Cell-SELEX, and biomarker candidates were isolated from the target cell lysates using the biotinylated pool DNAs. By virtue of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of the trypsinized candidate proteins, six and three biomarkers were identified for immature and mature DCs, respectively. Importantly, four and two of them were previously unknown biomarkers, demonstrating the effectiveness of AptaBiD.

Modified Cell-SELEX Targeting a Defined Transmembrane Protein

SELEX against cells ectopically displaying a target protein

Cell-SELEX can be applied for the generation of aptamers against a defined target protein displayed on live cells. Varieties of transmembrane proteins, including G protein-coupled receptors, receptor kinases, ion channels, are important targets for the development of molecular target drugs.35,36 Unfortunately, these proteins are usually difficult for the purification in their native conformations, and thus, Cell-SELEX is an attractive choice for the generation of aptamers recognizing native conformation of a transmembrane protein. This can be achieved via Cell-SELEX against cells ectopically expressing the target protein combining with a negative selection step employing parental mock cells. This strategy was examined by Cerchia et al.16,17 and by the author and colleagues.18,19 In these reports, antagonistic 2′-fPy-RNA aptamers against receptor tyrosine kinase RET and transforming growth factor-beta receptor type III (TbRIII) were successfully identified through the modified Cell-SELEX.16–19

Dead cell elimination in a positive selection step

Although above reports have demonstrated utility of the modified Cell-SELEX,16–19 the author also found technical difficulties of the procedure. In our experience, only one case out of ten independent examinations of the modified Cell-SELEX targeting TbRIII could successfully identify the intended aptamer (unpublished observations).

One problem is contamination of dead cells during the positive selection step. Because dead cells nonspecifically adsorb single-stranded nucleic acids, their contamination severely reduces the enrichment factor of the positive selection step.37 To overcome this problem, recovery of bound aptamers by chelating divalent cations would be useful.13,19 The formation of typical high-order RNA structures often requires divalent cations, and thus, its elimination (by adding EDTA, etc.) is expected to inactivate most of the bound aptamers. Because the elimination of divalent cations rarely affects the nonspecific adsorption of nucleic acids to dead cells, the chelation-based recovery may be an effective process to distinguish specific aptamers from nonspecific adsorbates (unpublished observations).

Alternatively, careful elimination of dead cells may be also purposeful.37 Raddatz et al. utilized fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for the positive selection step to eliminate dead cells and efficiently identified DNA aptamers against Burkitt lymphoma cells.20 The procedure, termed FACS-SELEX, has an additional advantage, that is, reduction of experimental steps in Cell-SELEX, because simultaneous performance of positive and negative selection steps can be achieved by FACS-SELEX.

Further improvements for the modified Cell-SELEX

Another problem causing the difficulty of the modified Cell-SELEX is imperfectness of a negative selection step. Several molecules displayed both on mock and target cells are expected to be highly abundant and would be fine (or easy) targets for aptamers. Thus, complete elimination of variants binding to them may be difficult even through repeated execution of a negative selection step (unpublished observations). As described above,9 addition of excess amount of known molecules binding to the desired target (i.e., natural ligands for the target molecule) may competitively release the target-specific aptamers, and can be utilized for the selective recovery of the desired aptamers. However, it should be noted that this procedure might not be effective for the recovery of extremely high-affinity aptamers and may lose the most valuable variants. In addition, noncompetitive aptamers cannot be recovered by the procedure. Because aptamers with intended binding and antagonistic property do not always compete with natural ligands, the procedure would reduce the variety of isolates.

Recent progress of high-throughput sequencing (HTSeq) technology may provide an alternative strategy for the identification of target molecule-specific aptamers through the modified Cell-SELEX. Because huge numbers of sequences can be obtained by HTSeq, target-specific variants would be identified by comparing the sequences of variants bound to the target-displaying cells and that to the mock cells even if the intended aptamers are not highly enriched in the pool. Recently, the HTSeq-based strategy was successfully applied for the identification of antibodies from phage-display libraries panned to antigen-expressing bacterial cells,38 and expected to be effective for the modified Cell-SELEX.

Cellular Uptake–Based SELEX

It has been reported that several aptamers identified through Cell-SELEX not only bind to the target cells, but also become intracellulary transported. For example, one of the aptamers (variant 2–16) selected against live T. brucei cells rapidly become internalized by endocytosis, and transported to lysosome by vesicular transport.7,10 Aptamers with such internalization property can be employed for intracellular drug delivery,39 and especially, utility of aptamer-mediated delivery of short interfering RNAs has been demonstrated.40,41

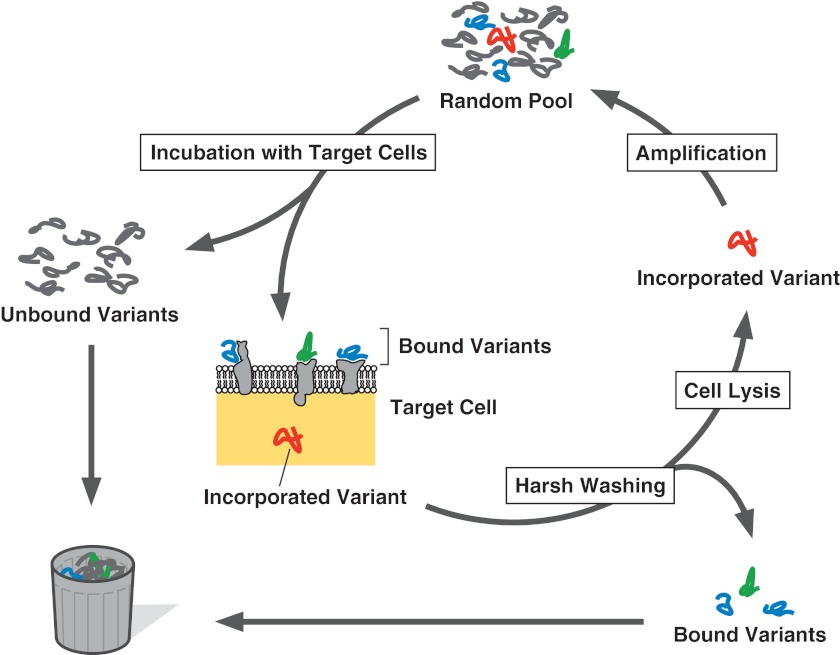

To generate aptamers that mediate target cell-specific, intracellular delivery of drugs, Wu et al. developed a unique SELEX strategy based on intracellular transport rather than binding (Fig. 2).21 In the strategy, a random pool is incubated with target cells, and not only unbound variants, but also variants bound to the cell surface are removed by extensive washing under harsh conditions (in their case, incubation with 0.2 M glycine-HCl, pH 4.0, for 5 min). Then, the incorporated variants are selectively recovered by cell lysis with proteinase and detergent. Employing the strategy, they identified DNA motifs that efficiently become transported into human chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells.21,22 Recently, similar strategy was applied for the generation of tRNA derivatives that can be incorporated into isolated mitochondria.42 The resulting RNA motifs may be utilized for the construction of a novel vector for mitochondrial disease therapies.

FIG. 2.

Cellular uptake-based SELEX. Not only unbound variants (gray), but also variants bound to the cell surface (blue and green) are removed by extensive washing under harsh conditions. The variant with the intended internalization property (red) is, then, recovered by cell lysis.

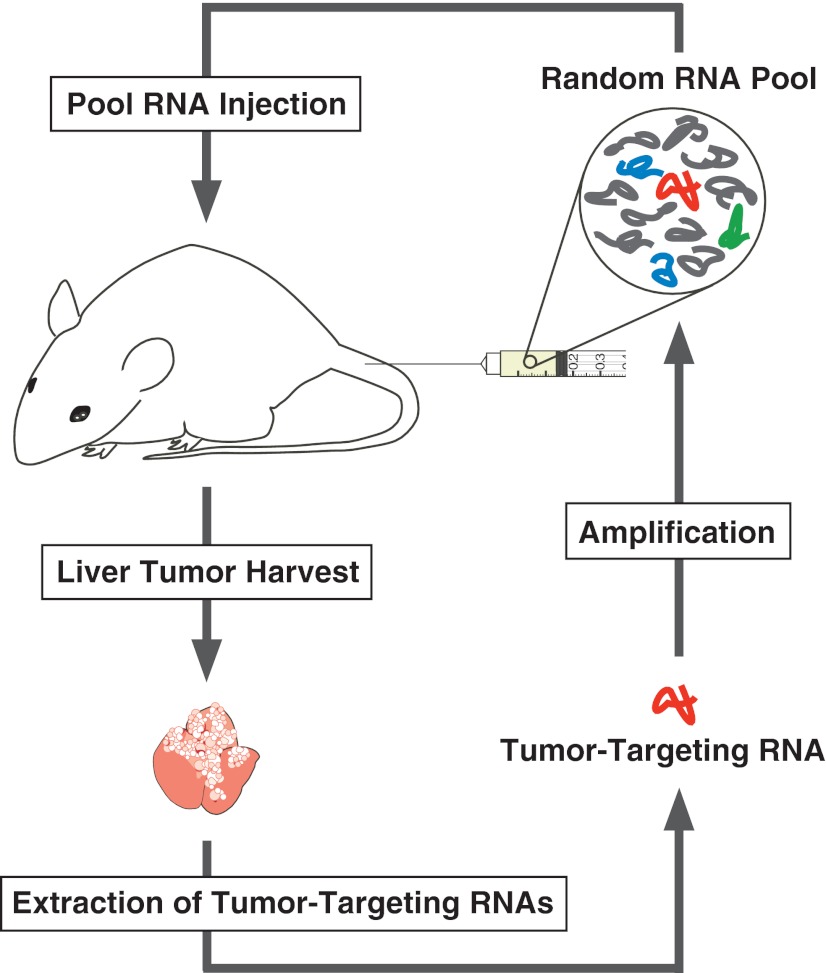

In the actual application of aptamers for the intracellular drug delivery, not only cellular uptake efficiency, but also pharmacokinetic parameters on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, restrict the intracellular availability. Mi et al. extended the cellular uptake–based SELEX to the selection under in vivo context (termed in vivo selection) employing a live tumor model animal (Fig. 3).23 A random 2′-fPy-RNA pool was intravenously injected into hepatic tumor-implanted mice. After 20-min circulation, the liver tumors were harvested, and the variants incorporated into the tumors were extracted, amplified, and employed for the next round of the injection. One of the isolates (variant 14–16) showed enhanced affinity for crude extract of the tumor cells and not for that of normal colon. When fluorescently labeled aptamer 14–16 was administered systematically via tail vein injection, the aptamer localized exclusively to the intrahepatic tumors, demonstrating successful enrichment of a desired variant by their procedure. Peptide mass fingerprinting analysis revealed that aptamer 14–16 recognizes p68, an RNA halicase that has been shown to be upregulated in colorectal cancer.

FIG. 3.

In vivo selection of tissue-targeting aptamers. A random pool is intravenously injected into a live animal, and after circulation, the target tissue (liver tumor) is harvested. Then, the variant with desired targeting property (red) is extracted and used for pool regeneration.

Application of Cell-Binding Aptamers

Finally, I would like to discuss the future aspects of application of cell-binding aptamers. As mentioned above, cell-binding aptamers would be applied for the development of target cell-specific molecular probes and drug delivery systems. Recently, Douglas et al. reported the unique delivery system employing DNA aptamers and DNA origami to specifically target-desired cells.43 In the system, drug molecules (antibodies against cell surface receptors) are encapsulated inside a three-dimensional DNA origami box, and the box is locked by hybridization of the aptamers and DNA oligomers with an antisense sequence of the aptamers. When target molecules on the cells bind to the aptamers, the structural change of the aptamers induces melting of the hybridization and unlocking of the box, resulting in the drug exposure. Thus, the drugs would be exposed only on the cells displaying the target molecules of the aptamers, and a highly specific drug delivery is expected. Aptamers identified through Cell-SELEX may be employed as the lock parts for this system.

Another application of cell-binding aptamers is the development of cell manipulation systems. For example, aptamer-immobilized resins can be utilized for the specific recovery of target cells.44–46 One advantage of the aptamer utilization is that they can be reversibly inactivated under mild conditions like antisense hybridization and divalent cation chelation. Therefore, it is possible to isolate the bound cells under the mild conditions and to use the resin repeatedly.47

Cell-specific aptamers can be employed for the specific adhesion of target cells.48,49 Schroeder et al. have developed a live-cell microarray employing peptide ligands and DNA microarray.50 In the system, target cell-binding peptide ligands are coupled with DNA oligomers and aligned onto DNA microarray through hybridization. When cells are applied onto this microarray, target cells are attached onto desired positions due to the affinities of the aligned peptide ligands. Gartner and Bertozzi have achieved a programmed spatial arrangement of multiple types of cells through hybridization of DNAs immobilized onto the cell surfaces.51 These cell manipulation systems are promising for the study and engineering of cell–cell communications. Although the DNAs are attached onto cells through affinities of peptide ligands or chemical coupling reactions in these reports, cell-binding aptamers may be utilized for such purposes.

While available biological affinity reagents are typically based on antibodies now, aptamers have several unique qualities that are of additional benefit as described in this review. I believe that advances on Cell-SELEX strategy, as well as application procedures of cell-binding aptamers, would open a door for the development of novel medical and biological technologies that cannot be achieved with antibodies.

Note added in proof

After the submission of this article, Thiel et al. reported the cellular uptake–based SELEX employing mouse carcinoma cells ectopically expressing HER2.52

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Prof. Sumiko Watanabe and Dr. Toshiro Iwagawa of IKAKEN (University of Tokyo, Japan) for the comments on this manuscript. The author's study was supported by the Young Investigator Promotion Fund Award from the Center for NanoBio Integration (University of Tokyo) and by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) from The Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, Science and Technology of Japan.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Klussmann S. The Aptamer Handbook: Functional Oligonucleotides and Their Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltenburg R. Reinemann C. Strehlitz B. SELEX—a (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands. Biomol Eng. 2007;24:381–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellington A. Szostak JW. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuerk C. Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vant-Hull B. Payano-Baez A. Davis RH, et al. The mathematics of SELEX against complex targets. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:579–597. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris KN. Jensen KB. Julin CM, et al. High affinity ligands from in vitro selection: complex targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2902–2907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homann M. Goringer HU. Combinatorial selection of high affinity RNA ligands to live African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2006–2014. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.9.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorger M. Engstler M. Homann M, et al. Targeting the variable surface of African trypanosomes with variant surface glycoprotein-specific, serum-stable RNA aptamers. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:84–94. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.1.84-94.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulrich H. Magdesian MH. Alves MJ, et al. In vitro selection of RNA aptamers that bind to cell adhesion receptors of Trypanosoma cruzi and inhibit cell invasion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20756–20762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homann M. Goringer HU. Uptake and intracellular transport of RNA aptamers in African trypanosomes suggest therapeutic “piggy-back” approach. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2571–2580. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shangguan D. Li Y. Tang Z, et al. Aptamers evolved from live cells as effective molecular probes for cancer study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11838–11843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602615103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo KT. Schäfer R. Paul A, et al. Aptamer-based strategies for stem cell research. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2007;7:701–705. doi: 10.2174/138955707781024481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang Z. Parekh P. Turner P, et al. Generating aptamers for recognition of virus-infected cells. Clin Chem. 2009;55:813–822. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.113514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blank M. Weinschenk T. Priemer M, et al. Systematic evolution of a DNA aptamer binding to rat brain tumor microvessels. Selective targeting of endothelial regulatory protein pigpen. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16464–16468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berezovski MV. Lechmann M. Musheev MU, et al. Aptamer-facilitated biomarker discovery (AptaBiD) J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9137–9143. doi: 10.1021/ja801951p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerchia L. Duconge F. Pestourie C, et al. Neutralizing aptamers from whole-cell SELEX inhibit the RET receptor tyrosine kinase. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Cerchia L. D'Alessio A. Amabile G, et al. An autocrine loop involving ret and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor mediates retinoic acid-induced neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:481–488. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohuchi SP. Ohtsu T. Nakamura Y. A novel method to generate aptamers against recombinant targets displayed on the cell surface. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 2005;49:351–352. doi: 10.1093/nass/49.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohuchi SP. Ohtsu T. Nakamura Y. Selection of RNA aptamers against recombinant transforming growth factor-beta type III receptor displayed on cell surface. Biochimie. 2006;88:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raddatz MS. Dolf A. Endl E, et al. Enrichment of cell-targeting and population-specific aptamers by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:5190–5193. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu CC. Castro JE. Motta M, et al. Selection of oligonucleotide aptamers with enhanced uptake and activation of human leukemia B cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:849–860. doi: 10.1089/104303403765701141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mende M. Hopert A. Wünsche W, et al. A hexanucleotide selected for increased cellular uptake in cis contains a highly active CpG-motif in human B cells and primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunology. 2007;120:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mi J. Liu Y. Rabbani ZN, et al. In vivo selection of tumor-targeting RNA motifs. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:22–24. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen F. Zhou J. Luo F, et al. Aptamer from whole-bacterium SELEX as new therapeutic reagent against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi R. Janagama H. Dwivedi HP, et al. Selection, characterization, and application of DNA aptamers for the capture and detection of Salmonella enterica serovars. Mol Cell Probes. 2009;23:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YJ. Han SR. Maeng JS, et al. In vitro selection of Escherichia coli O157:H7-specific RNA aptamer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H. Ding X. Peng Z, et al. Aptamer selection for the detection of Escherichia coli K88. Can J Microbiol. 2011;57:453–459. doi: 10.1139/w11-030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao X. Li S. Chen L, et al. Combining use of a panel of ssDNA aptamers in the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4621–4628. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan N. Wu S. Chen X, et al. Selection and identification of a DNA aptamer targeted to Vibrio parahemolyticus. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:4034–4038. doi: 10.1021/jf300395z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dwivedi HP. Smiley RD. Jaykus LA. Selection and characterization of DNA aptamers with binding selectivity to Campylobacter jejuni using whole-cell SELEX. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;87:2323–2334. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2728-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamula CL. Le XC. Li XF. DNA aptamers binding to multiple prevalent M-types of Streptococcus pyogenes. Anal Chem. 2011;83:3640–3647. doi: 10.1021/ac200575e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y. Chen Y. Han D, et al. Aptamers selected 1 by cell-SELEX for application in cancer studies. Bioanalysis. 2010;2:907–918. doi: 10.4155/bio.10.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips JA. Lopez-Colon D. Zhu Z, et al. Applications of aptamers in cancer cell biology. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;621:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwagawa T. Ohuchi SP. Watanabe S, et al. Selection of RNA aptamers against mouse embryonic stem cells. Biochimie. 2012;94:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hopkins AL. Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:727–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rask-Andersen M. Almen MS. Schiöth HB. Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avci-Adali M. Metzger M. Perle N, et al. Pitfalls of cell-systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX): existing dead cells during in vitro selection anticipate the enrichment of specific aptamers. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:317–323. doi: 10.1089/oli.2010.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H. Torkamani A. Jones TM, et al. Phenotype-information-phenotype cycle for deconvolution of combinatorial antibody libraries selected against complex systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13456–13461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111218108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farokhzad OC. Jon S. Khademhosseini A, et al. Nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates: a new approach for targeting prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7668–7672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu TC. Twu KY. Ellington AD, et al. Aptamer mediated siRNA delivery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNamara JO., 2nd Andrechek ER. Wang Y, et al. Cell type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nbt1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolesnikova O. Kazakova H. Comte C, et al. Selection of RNA aptamers imported into yeast and human mitochondria. RNA. 2010;16:926–941. doi: 10.1261/rna.1914110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Douglas SM. Bachelet I. Church GM. A logic-gated nanorobot for targeted transport of molecular payloads. Science. 2012;335:831–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1214081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JE. Medley CD. Tang Z, et al. Aptamer-conjugated nanoparticles for the collection and detection of multiple cancer cells. Anal Chem. 2007;79:3075–3082. doi: 10.1021/ac062151b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herr JK. Smith JE. Medley CD, et al. Aptamer-conjugated nanoparticles for selective collection and detection of cancer cells. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2918–2924. doi: 10.1021/ac052015r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schäfer R. Wiskirchen J. Guo K, et al. Aptamer-based isolation and subsequent imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in ischemic myocard by magnetic resonance imaging. Rofo. 2007;179:1009–1015. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nomura Y. Sugiyama S. Sakamoto T, et al. Conformational plasticity of RNA for target recognition as revealed by the 2.15 Å crystal structure of a human IgG-aptamer complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7822–7829. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo K. Wendel HP. Scheideler L, et al. Aptamer-based capture molecules as a novel coating strategy to promote cell adhesion. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:731–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo KT. Schafer R. Paul A, et al. A new technique for the isolation and surface immobilization of mesenchymal stem cells from whole bone marrow using high-specific DNA-aptamers. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2220–2231. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroeder H. Ellinger B. Becker CF, et al. Generation of live-cell microarrays by means of DNA-directed immobilization of specific cell surface ligands. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:4180–4183. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gartner ZJ. Bertozzi CR. Programmed assembly of 3-dimensional microtissues with defined cellular connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4606–4610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900717106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiel KW. Hernandez LI. Dassie JP, et al. Delivery of chemo-sensitizing siRNAs to HER2+-breast cancer cells using RNA aptamers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6319–6337. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]