Abstract

Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (IF/TA) contributes to the loss of kidney allografts, and treatment or preventive options are lacking. We conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether angiotensin II blockade prevents the expansion of the cortical interstitial compartment, the precursor of fibrosis. We randomly assigned 153 transplant recipients to receive losartan, 100 mg (n=77), or matching placebo (n=76) within 3 months of transplantation, continuing treatment for 5 years. The primary outcome was a composite of doubling of the fraction of renal cortical volume occupied by interstitium from baseline to 5 years or ESRD from IF/TA. In the intention-to-treat analysis, using only patients with adequate structural data, the primary endpoint occurred in 6 of 47 patients who received losartan and 12 of 44 who received placebo (odds ratio [OR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13–1.15; P=0.08). We found no significant effect of losartan on time to a composite of ESRD, death, or doubling of creatinine level. In a secondary analysis, losartan seemed to reduce the risk of a composite of doubling of interstitial volume or all-cause ESRD (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.13–0.99; P=0.05), but this finding requires validation. In conclusion, treatment with losartan did not lead to a statistically significant reduction in a composite of interstitial expansion or ESRD from IF/TA in kidney transplant recipients.

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA) in renal allografts, previously termed chronic allograft nephropathy, is a major cause of long-term renal graft dysfunction and loss.1,2 Strategies used to slow the progression of native kidney disease, such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade and strict BP control, have not been formally tested for the prevention or treatment of IF/TA. Expansion of the interstitial compartment is a major component of IF/TA. Multiple studies have demonstrated a direct relationship between interstitial expansion and renal allograft functional decline3–5 and graft failure.6–10 Interstitial expansion is amenable to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. In a 2-year multicenter, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes, Cordonnier et al. found that the ACE inhibitor perindopril prevented expansion of cortical interstitial volume, whereas the placebo group, despite having similar BP and glycemic control, had almost a doubling of that measure.5 We therefore conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 5-year trial in kidney transplant recipients to determine whether angiotensin II blockade could slow or prevent cortical interstitial volume expansion or graft loss from IF/TA. The hypothesis was that abrogating the fibrogenic effects of angiotensin II and ameliorating the hemodynamic consequences of reduced nephron number would reduce structural damage in transplanted kidneys.

Results

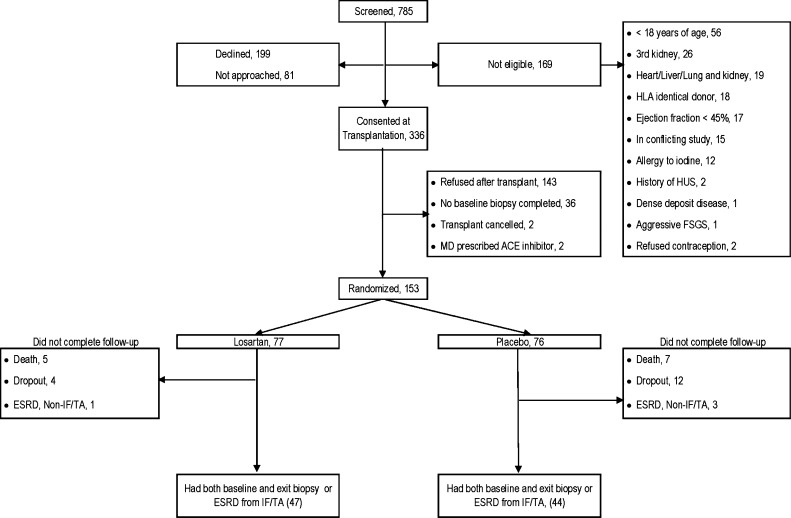

Of the 336 patients who consented at the time of transplantation, 153 recipients consented to be randomly assigned to 100 mg of losartan per day or placebo an average of 58±34 days after transplantation (Figure 1). Age, sex, source of kidney, cause of native kidney disease, and ethnicity were similar for randomly assigned patients, those who declined participation or were not approached (n=280), and those who consented at the time of transplantation but never reached the randomization visit (n=183). The study groups were similar for all baseline characteristics (Table 1). Mean age ± SD at transplantation was 48.7±12.4 years. Most participants were white, had received a kidney from a live donor, and were having their first transplantation; more than one third had diabetes. University of Minnesota participants (n=126) received anti-thymocyte globulin induction and only 5 days of corticosteroids, and Hennepin County Medical Center participants (n=27) received induction with an IL-2 antagonist and continued to receive maintenance steroids. All participants received a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) and mycophenolate mofetil as maintenance immunosuppression. Blood levels of calcineurin inhibitors were similar between the two groups during the entire study. The mean serum creatinine level at randomization was 1.4±0.4 mg/dl in both groups; the iothalamate GFR was 55.8±18.8 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the losartan group and 56.4±15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the placebo group. Measured values of fraction of renal cortical volume occupied by interstitium (VvInt/cortex) at baseline were 0.19±0.04 in the losartan group and 0.18±0.05 in placebo group (P=0.35). During the trial, 12 patients reached the study endpoint of ESRD from biopsy-proven IF/TA and 32 participants did not reach the 5-year exit biopsy (12 because of death and 4 because of ESRD not related to IF/TA [2 from recurrent disease and 2 from polyoma virus nephropathy]). In addition, 16 patients withdrew 17.8±14.2 months after randomization. Most withdrawals occurred because participants did not want to return for annual visits (n=10) or because they were prescribed ACE inhibitors (n=6) outside of the study. The mean serum creatinine level in these 16 participants at 5 years after transplantation was 1.49±0.69 mg/dl, similar to the level in patients who reached the final visit.

Figure 1.

Study participants. HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients | Losartan Group | Placebo Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 153 | 77 | 76 | |

| Age at transplant (yr) | 48.7±12.4 | 49.4±11.1 | 48.0±13.6 | 0.50 |

| Men, n (%) | 94 (61.4) | 47 (61.0) | 47 (61.8) | 1.00 |

| White patients, n (%) | 133 (86.9) | 66 (85.7) | 67 (88.2) | 0.81 |

| Cause of kidney disease, n (%) | 0.19 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 (37.3) | 28 (36.4) | 29 (38.2) | |

| Hypertension | 10 (6.5) | 8 (10.4) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 23 (15.0) | 13 (16.9) | 10 (13.2) | |

| Other | 63 (41.2) | 28 (36.4) | 35 (46.1) | |

| Live donor, n (%) | 108 (70.6) | 53 (68.8) | 55 (72.4) | 0.72 |

| First transplant, n (%) | 132 (86.3) | 69 (89.6) | 63 (82.9) | 0.25 |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | ||||

| CNI + MMF | 115 (75.2) | 59 (76.6) | 56 (73.7) | 0.41 |

| CNI + sirolimus | 21 (13.7) | 8 (10.4) | 13 (17.1) | |

| Other | 17 (11.1) | 10 (13.0) | 7 (9.2) | |

| Prednisone use, n (%) | 42 (27.4) | 18 (23.4) | 24 (31.6) | 0.28 |

| Pancreas transplant, n (%) | 30 (19.6) | 15 (19.5) | 15 (19.7) | 1.00 |

| Acute rejection between transplant and randomization, n (%) | 12 (7.8) | 7 (9.1) | 5 (6.6) | 0.77 |

| Time to randomization (d) | 58.3±33.8 | 61.5±37.2 | 55.1±29.8 | 0.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4±5.1 | 26.6±5.1 | 26.3±5.2 | 0.78 |

| No. of HLA matches | 2.3±1.6 | 2.1±1.6 | 2.5±1.5 | 0.19 |

| Cold ischemia time (h)a | 17.1±6.8 | 14.9±6.1 | 19.7±6.8 | 0.02 |

| Diuretic use, n (%) | ||||

| Loop | 39 (25.5) | 20 (26.0) | 19 (25.0) | 1.00 |

| Thiazide | 12 (7.8) | 6 (7.8) | 6 (7.9) | 1.00 |

| BP (mmHg) | ||||

| Systolic | 130.5±18.3 | 130.1±18.1 | 130.9±18.6 | 0.80 |

| Diastolic | 73.5±10.7 | 74.0±11.9 | 73.1±9.4 | 0.60 |

| Panel-reactive antibodies, n (%) | 104 (67) | 52 (67) | 51 (67) | 0.54 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.4±1.4 | 11.3±1.4 | 11.5±1.5 | 0.45 |

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g) | 23.6±10.3 | 24.4±10.0 | 23.3±11.7 | 0.73 |

| Urine protein (g/d) | 0.34±0.24 | 0.34±0.25 | 0.34±0.21 | 0.72 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.4±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 | 0.40 |

| GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 56.1±17.0 | 55.8±18.8 | 56.4±15.0 | 0.82 |

| VvInt/cortex | 0.19±0.05 | 0.19±0.04 | 0.18±0.5 | 0.35 |

Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean ± SD. CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; MMP, mycophenolate mofetil; BMI, body mass index.

For deceased donors.

Primary Outcome

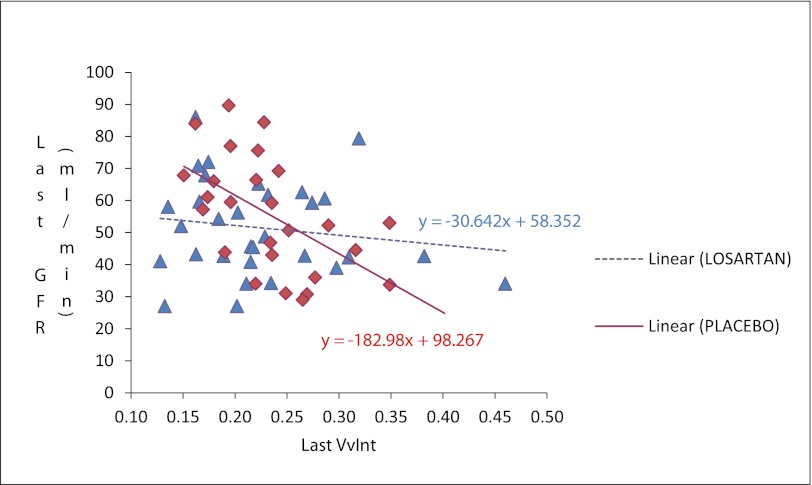

Analysis of recipients who could be assessed for the study's prespecified primary endpoint (i.e., who had adequate baseline and exit biopsy samples or who developed ESRD from IF/TA) showed that doubling of (VvInt/cortex) or ESRD from IF/TA occurred in 6 of 47 patients in the losartan group versus 12 of 44 in the placebo group (odds ratio [OR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13–1.15; P=0.08). Adjustment for center and maintenance steroid use gave similar results. The baseline biopsy specimen was not adequate for morphometric analysis in 31 patients. No baseline clinical or demographic differences were seen between patients with and those without adequate baseline biopsy specimens (data not shown). In addition, 12 exit biopsies were not performed because of technical difficulties, inability to stop anticoagulation, or patient refusal. Clinical, demographic, and baseline biopsy characteristics of patients missing the 5-year biopsy did not differ from those of the other trial participants. At 5 years, VvInt/cortex was 0.22±0.07 in the losartan group and 0.24±0.06 in the placebo group (P=0.45). The mean change in VvInt/cortex was 0.03±0.9 in the losartan group versus 0.06±0.08 in the placebo group (P=0.23). The relationship between GFR at last visit and VvInt/cortex in the exit biopsy specimens is shown in Figure 2. A 10% increase in VvInt/cortex was associated with decreases in GFR of 18.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the placebo group and 3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in the losartan group (P=0.03 for difference in slopes).

Figure 2.

Iothalamate GFR and VvInt/Cortex at study exit.

Secondary Outcomes

When all cases of ESRD (5 cases in losartan-treated and 11 in placebo-treated patients) were considered in the composite endpoint, 7 of 48 and 15 of 47 reached the endpoint in the losartan and placebo groups, respectively (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.13–0.99; P=0.05) (Table 2). Ten patients in the losartan group and 14 in the placebo group died at any time after randomization (hazard ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.31–1.61; P=0.43). Causes of death were similar between the two groups (data not shown). Nineteen of 77 patients in the losartan group reached the more conventional endpoint of time to the earliest of death, ESRD, or doubling of serum creatinine level versus 24 of 76 patients in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.40–1.33; P=0.30). Of note, the mean time to doubling of serum creatinine level was 1065 days in the losartan group compared with 450 days in the placebo group.

Table 2.

Comparison of treatment groups for primary and secondary outcomes

| Variable | Losartan Group (n=77) | Placebo Group (n=76) | OR or HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| Doubling of interstitium or ESRD from IF/TA | 6/47 | 12/44 | OR, 0.39 (0.13–1.15) | 0.08 |

| Doubling of interstitium | 2/47 | 4/44 | OR, 0.44 (0.08–2.56) | 0.42 |

| ESRD from IF/TA | 4/47 | 8/44 | OR, 0.42 (0.12–1.50) | 0.22 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||

| Doubling of interstitium or any ESRD | 7/48 | 15/47 | OR, 0.36 (0.13–0.99) | 0.05 |

| Doubling of interstitium | 2/47 | 4/44 | OR, 0.44 (0.08–2.56) | 0.42 |

| All cause ESRD | 5/48 | 11/47 | OR, 0.38 (0.12–1.20) | 0.09 |

| Time to death any time after randomization | 10/77 | 14/76 | HR, 1.38 (0.62–3.20) | 0.44 |

| Time to earliest of death, any ESRD, or doubling of creatinine | 19/77 | 24/76 | HR, 1.37 (0.75–2.53) | 0.30 |

| Doubling of creatinine | 9/77 | 12/76 | HR, 7.28 (2.22–32.78) | <0.01 |

| All cause ESRD | 4/77 | 5/76 | HR, 0.54 (0.10–2.47) | 0.42 |

| Death | 6/77 | 7/76 | HR, 0.90 (0.28–3.13) | 0.85 |

HR, hazard ratio.

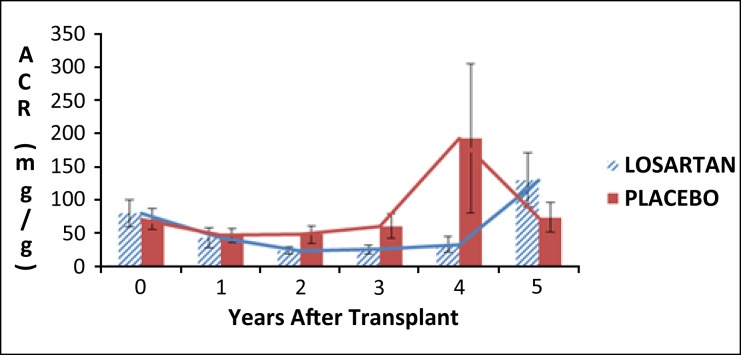

Urinary protein, whether expressed as albumin-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour urine protein or albumin, was similar between the two groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean urinary albumin excretion (expressed as albumin-to-creatinine ratio). Error bars are ± 1 SE

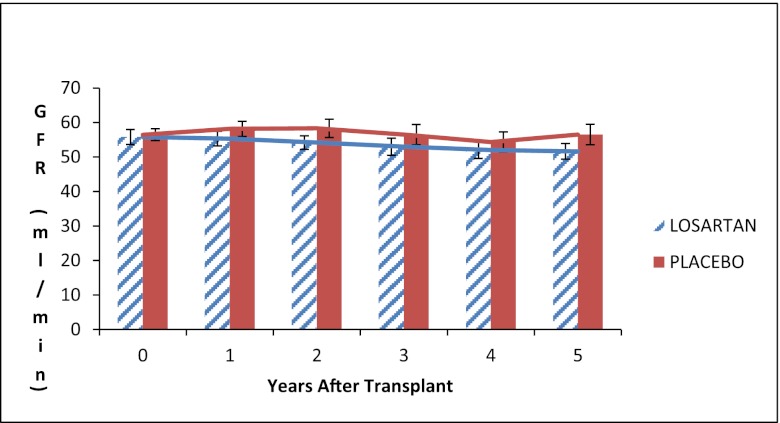

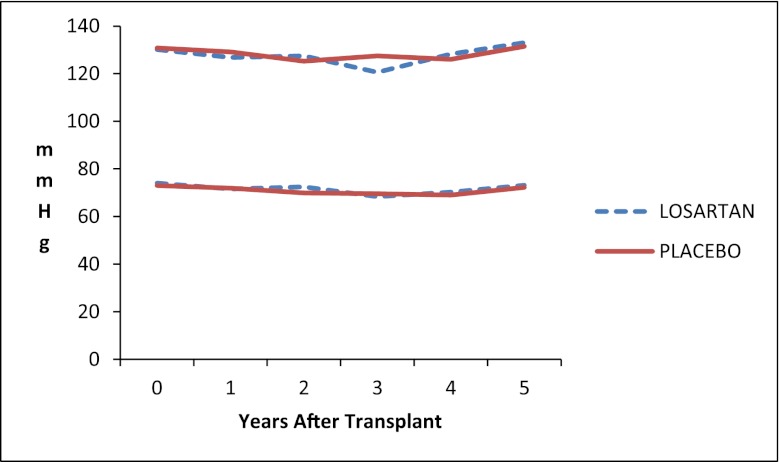

Iothalamate GFR did not differ between the two groups at any follow-up time after baseline (Figure 4). Systolic and diastolic BPs were similar in the two groups during the 5 years of the study (Figure 5); the average systolic BP was 127±17.6 mmHg in the losartan group and 129±19.9 mmHg in the placebo group at 1 year after randomization and 133±15.6 versus 131±14.5 mmHg, respectively, at the 5-year follow-up visit.

Figure 4.

Iothalamate GFR. Error bars are ± 1 SE

Figure 5.

Mean systolic and diastolic BP.

Adherence and Adverse Events

Patients self-reported missing the study drug on 8.8% of the days in year 1. This rate declined to 1.9% in the last year of the trial. In all, 87% of patients were judged adherent for their entire time in the study. A total of 291 adverse events were reported, averaging 1.71 adverse events per participant in the losartan group and 2.09 in the placebo group (P=NS) (Table 3). Seven participants in the losartan group developed noncutaneous cancers (three adenocarcinomas, one renal cell carcinoma, one lymphoma, one bladder cancer, and one unknown primary cancer) versus six in the placebo group (one lymphoma, one cervical cancer, two adenocarcinoma, one central nervous system tumor, and one unknown). Serum potassium level was consistently 0.1–0.3 mEq/L higher in the losartan group, and hyperkalemia (potassium level > 5.4 mEq/L) was observed intermittently in 17 of 77 (22.1%) patients in the losartan group and 5 of 76 (6.6%) patients in the placebo group (P=0.01). Only one serious hyperkalemia event (potassium level > 6.0 mEq/L) occurred in a losartan-treated participant.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Adverse Event | Patients with Adverse Events (n) | Total Adverse Events (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losartan Group (n = 77) | Placebo Group (n = 76) | P Valuea | Losartan Group (n = 77) | Placebo Group (n = 76) | P Valueb | |

| Bacterial infection | 11 | 10 | 1.00 | 15 | 15 | 0.98 |

| Cardiovascular | 9 | 9 | 1.00 | 9 | 11 | 0.64 |

| Death, unknown cause | 2 | 0 | 0.50 | 2 | 0 | NA |

| Digestive | 8 | 14 | 0.17 | 15 | 18 | 0.70 |

| Endocrine | 10 | 18 | 0.10 | 10 | 28 | 0.01 |

| Fungal/other infection | 2 | 4 | 0.44 | 2 | 6 | 0.20 |

| Hematologic | 3 | 5 | 0.49 | 5 | 10 | 0.37 |

| Musculoskeletal | 14 | 9 | 0.37 | 19 | 12 | 0.31 |

| Other/unknown | 11 | 8 | 0.63 | 14 | 10 | 0.51 |

| Rejection | 7 | 8 | 0.79 | 12 | 9 | 0.63 |

| Respiratory | 3 | 5 | 0.49 | 7 | 6 | 0.86 |

| Urogenital | 12 | 21 | 0.08 | 16 | 26 | 0.14 |

| Viral infection | 5 | 8 | 0.40 | 6 | 8 | 0.59 |

NA, not applicable; can't be calculated due to small number of events.

Fisher exact test.

Negative binomial test.

Discussion

Losartan was not associated with a statistically significant benefit in the primary outcome, prevention of interstitial expansion or graft loss from IF/TA in kidney transplant recipients. Losartan appeared marginally protective for the prespecified secondary composite endpoint of (VvInt/cortex) doubling and all-cause ESRD, but this would require independent corroboration. Losartan was well tolerated, and, despite a higher level of serum potassium, only one case of severe hyperkalemia (potassium level > 6 mEq/L) occurred.

Blockers of the renin-angiotensin system are more effective than other antihypertensive agents in reducing time to dialysis, death, or doubling of serum creatinine level in patients with reduced GFR.11–13 These drugs also prevent progression of proteinuria but to our knowledge have never been shown to reduce structural damage or ESRD in patients with preserved kidney function. In fact, neither losartan nor enalapril prevented expansion of the fractional volume of interstitium in normoalbuminuric, normotensive patients with type 1 diabetes and normal or high GFR who were treated for 5 years.14 A retrospective analysis by Heinze et al.15 found evidence supporting a benefit of renin-angiotensin system blockers in kidney transplant recipients, but a 2-year randomized trial with losartan versus placebo showed no structural benefit or favorable effect on allograft function.16

A possible explanation for the lack of clear and robust benefit of losartan in our study, which has been repeatedly observed in relatively advanced native kidney disease, is that ours was a primary prevention trial that included many relatively low-risk patients: Most were white recipients of live-donor kidney transplants and had low immunologic risk. However, studies have documented progressive structural changes in renal allografts in patients with profiles similar to those of the patients in this trial.17 The degree of intersitial expansion in our patients is clearly less than has been described in the literature, and few events occurred. Our original sample size estimate and power calculations predicted that 60% of placebo-treated patients will double their cortical interstitial fractional volume (the major component of the primary outcome) or reach ESRD from IF/TA (Supplemental material, Appendix 1). At the end of the 5-year trial, however, fewer patients than expected reached that endpoint. This finding is in line with the emerging data from serial protocol biopsies indicating the declining prevalence of interstitial fibrosis in recent years that could not have been predicted a decade ago.18,19 In the study by Stegall et al., only 23% of recipients with mild fibrosis 1 year after transplantation progressed to more severe injury.19 Thus, the trend toward a treatment benefit and lack of clear harm noted here despite the lower than expected event rate compared with that originally projected from earlier-era data supports the performance of a larger trial to answer this question more definitively. The relationship between the final GFR and VvInt/cortex seems to suggest that expansion of this compartment may be less detrimental to GFR in patients receiving losartan, but it also indicates that much of the variability in GFR may not be accounted for by the change in VvInt/cortex.

The benefit of strict BP control in kidney transplant recipients has been demonstrated in many observational studies and is linked to more favorable outcomes for the graft and also for recipient survival.20 This has not been shown in prospective studies in which recipients were randomly assigned to two levels of BP control. It is possible that the low event rate in the present trial arose from the superior BP control achieved in the trial. It may also suggest the importance of BP control regardless of which agent is used to achieve it. The unavailability of renal tissue that is adequate for careful morphometric measurements in some participants is a significant limitation. However, because most of these kidneys were from live young donors, it is very unlikely that major histologic abnormalities were missed at baseline. Of note, formal comparison in patients with and those without biopsy revealed no systemic differences and showed that biopsies were indeed missing at random.

This randomized trial suggests that angiotensin II blockade is safe. The failure to detect a clear benefit of such blockade on renal structure agrees with what has been observed early on in renal involvement in type 1 diabetes but is at odds with the benefits demonstrated in patients with established CKD. Both immunologic and nonimmunologic factors conspire to lead to interstitial fibrosis of the renal allograft. It remains plausible that mitigating the nonimmunologic damage to the allograft through angiotensin II blockade could reduce intersitial expansion in renal allografts. We believe that these data provide extremely important information that attest to the safety of angiotensin II blockade and provide a contemporary account for the evolution of renal structure on renal allografts that can be used to design future interventional trials.

Concise Methods

The Angiotensin II Blockade in Chronic Allograft Nephropathy (ABCAN) trial (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01467895) was carried out at two transplant centers, the University of Minnesota and Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This investigator-initiated study was sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and Merck, Inc., which donated the study drugs. The study was approved by the relevant institutional review boards, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The study began in December 2002 and closed out on June 30, 2011. It was overseen by a data and safety monitoring board that met four times before it was reconstituted in June 2009 as part of transitioning the study into a cooperative agreement (U01) with the NIDDK, after which it met twice more.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years in patients receiving a first or a second kidney transplant alone or in combination with a pancreas transplant. Exclusion criteria were serum creatinine level ≥2.5 mg/dl at the time of randomization, persistent hyperkalemia (potassium level > 5.4 mEq/L), known hypersensitivity to losartan or iodine allergy, documented allograft artery stenosis, recipients of grafts from HLA-identical siblings, primary renal diseases with high recurrence risk (such as primary hyperoxaluria, dense-deposit disease, severe FSGS, and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome). Women of childbearing age who wished to become pregnant or were unwilling to use contraceptives during the trial and recipients requiring ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers for a cardiovascular indication (e.g., systolic dysfunction) were excluded. Participants were approached while they were on the deceased-donor waiting list, during their evaluation for living-donor kidney transplantation, or at the time of transplantation. Those who consented to be in the trial underwent a postperfusion biopsy; if that was not feasible, they underwent a kidney biopsy in the early post-transplant period.

Study Design

In the first 3 months after transplantation, patients were randomly assigned to 100 mg of losartan per day or placebo with an allocation ratio of 1:1 using computer-generated blocks size 2–6 and stratified according to donor age (<55 years versus ≥55 years), estimated GFR (<35 versus ≥35 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and acute rejection before randomization (yes or no). A key premise of this trial was that losartan would exert its beneficial effect independently of its BP-lowering properties. Therefore, every effort was made to keep BP similar in the two treatment groups, with targets for systolic BP of <130 mmHg and diastolic BP of <80 mmHg. To achieve these goals, calcium-channel blockers were used as first-line therapy, with diuretics as second-line and β-blockers as third-line. Use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II blockers was prohibited. Losartan was chosen over an ACE inhibitor for its absence of the adverse effect of cough, propensity to cause less hyperkalemia, and proven safety in terms of post-transplant erythrocytosis.

Study Endpoints

The prespecified primary study endpoint was a composite: ESRD from IF/TA or doubling in VvInt/cortex measured in kidney biopsy specimens obtained at the time of transplantation and 5 years later. Secondary outcomes included doubling of (VvInt/cortex) and all-cause ESRD, changes in urinary albumin excretion rate and iothalamate GFR, and also the more conventional composite endpoint of time to doubling of serum creatinine level, ESRD from any cause, or death.

Measurements

(VvInt/cortex) was measured by a single observer masked to study drug assignments. Cortical interstitial fractional volume was estimated by point counting, as described elsewhere21 and detailed in Supplemental material Appendix 2. In brief, the number of points falling on the interstitium relative to those falling on cortical tissue were counted. The interstitial space was defined as the area of cortex not containing glomeruli, tubules, or blood vessels larger than the average tubular diameter. A minimum of 65 points was considered sufficient because it provided a stable estimate of VvInt/cortex. This was decided jointly with a panel of stereology experts who were asked by NIDDK to determine the appropriate number of points needed to assess the primary outcome accurately. Pill counts and measurements of BP, urinary albumin excretion rate, and GFR were assessed annually. GFR was measured annually by urinary clearance of iothalamate. The coefficient of variation of the iothalamate GFR was <8%. The study drug was discontinued 1 month before the last GFR and urinary protein and albumin measurements, which were made at the time of the exit biopsy at 5-year follow-up. Urinary protein was measured in early morning voided urine samples at the annual GFR measurement visits and also from a 24-hour urine collection obtained the day before the five annual visits. All procedures and assays were performed at the University of Minnesota site.

Sample Size Determination and Statistical Analyses

We hypothesized that during a 5-year period, angiotensin II receptor blockade with losartan would reduce by 60% the proportion of patients who doubled their cortical interstitial fractional volume or lost their graft from biopsy-proven IF/TA. When the study was designed in 2001, the only information available about the rate of expansion of VvInt/cortex came from our studies in diabetic transplant recipients in whom (Vvlnt/cortex) increased universally over a 5-year period, and for the effect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade on rate of expansion in the interstitial compartment, we used data from Cordonnier et al. in which an ACE inhibitor given for 2 years to patients with type 2 diabetes and proteinuria completely prevented expansion of the interstitial compartment compared with a universal increase in all controls.5,22 We allowed for a 10% dropout rate and attrition due to patient death and graft failure from causes other than IF/TA. Given these considerations, a sample size of 68 participants per group provided >90% power to detect a group difference in the primary endpoint. At the second planned interim analysis, the data safety and monitoring board recommended recruiting a total of 154 patients because some participants were prescribed ACE inhibitors and some baseline biopsy specimens were deemed inadequate. With these new additional participants, it was predicted that a total of 90 patients would have to be ascertained for the primary outcome to maintain ≥80% power. For detailed sample size and power consideration, please see Supplemental material Appendix 1.

Baseline characteristics were compared using chi-squared and t tests. All outcome analyses were according to randomization treatment assignments (intention to treat). The study groups were compared for the primary outcome using the Fisher exact test. Secondary outcomes measured at each annual visit were compared between treatment groups using mixed linear models. For each patient, all available data from annual visits were included. All analyses included treatment group and follow-up visit number (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) as fixed effects; patients were treated as a random effect, and errors within patients were modeled as having correlation that decayed exponentially with time between measurement visits. Common logarithms of urine protein, urine albumin excretion rate (24-hour collections), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios were used as outcomes in place of the raw measurements because the latter had highly skewed distributions. Analysis of time to the earliest of death, all-cause ESRD, or doubling of serum creatinine used Kaplan-Meier plots and Cox regression.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ann Palmer and John Basgen, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, for performing all the morphometric studies.

The first author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work was supported by NIDDK, U01 DK060706-09, and Merck Inc. donated losartan and the placebo.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Angiotensin II Blockade after Kidney Transplantation,” on pages 167–168.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012080777/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nankivell BJ, Chapman JR: Chronic allograft nephropathy: Current concepts and future directions. Transplantation 81: 643–654, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ, Kremers WK, Amer H, Gloor JM, Cosio FG: Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss. Am J Transplant 9: 527–535, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohle A, Müller GA, Wehrmann M, Mackensen-Haen S, Xiao JC: Pathogenesis of chronic renal failure in the primary glomerulopathies, renal vasculopathies, and chronic interstitial nephritides. Kidney Int 54[Supp]: 2–9, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amico G: Tubulointerstitium as predictor of progression of glomerular diseases. Nephron 83: 289–295, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordonnier DJ, Pinel N, Barro C, Maynard M, Zaoui P, Halimi S, Hurault de Ligny B, Reznic Y, Simon D, Bilous RW, The Diabiopsies Group : Expansion of cortical interstitium is limited by converting enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients with glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1253–1263, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serón D, Carrera M, Griño JM, Castelao AM, Lopez-Costea MA, Riera L, Alsina J: Relationship between donor renal interstitial surface and post-transplant function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 8: 539–543, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leunissen KM, Bosman FT, Nieman FH, Kootstra G, Vromen MA, Noordzij TC, van Hooff JP: Amplification of the nephrotoxic effect of cyclosporine by preexistent chronic histological lesions in the kidney. Transplantation 48: 590–593, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang HJ, Kjellstrand CM, Cockfield SM, Solez K: On the influence of sample size on the prognostic accuracy and reproducibility of renal transplant biopsy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 165–172, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickerson P, Jeffery J, Gough J, McKenna R, Grimm P, Cheang M, Rush D: Identification of clinical and histopathologic risk factors for diminished renal function 2 years posttransplant. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 482–487, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isoniemi H, Taskinen E, Häyry P: Histological chronic allograft damage index accurately predicts chronic renal allograft rejection. Transplantation 58: 1195–1198, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD, The Collaborative Study Group : The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 329: 1456–1462, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I, Collaborative Study Group : Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner JM, Bauer C, Abramowitz MK, Melamed ML, Hostetter TH: Treatment of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 81: 351–362, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauer M, Zinman B, Gardiner R, Suissa S, Sinaiko A, Strand T, Drummond K, Donnelly S, Goodyer P, Gubler MC, Klein R: Renal and retinal effects of enalapril and losartan in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 361: 40–51, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinze G, Mitterbauer C, Regele H, Kramar R, Winkelmayer WC, Curhan GC, Oberbauer R: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist therapy is associated with prolonged patient and graft survival after renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 889–899, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campistol JM, Garcia Del Moral R, Alarcon A, Gonzalez-Molina M, Arias M, Morales JM, Lauzurica R, Grinyo JM, Del Castillo D, Valdes F, Seron D, Ortega F:, Angiotensin II. receptor blockage in kidney transplantation. Design and progress of the allograft study [Abstract]. Transplantation 82: 238, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O’Connell PJ, Allen RD, Chapman JR: The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med 349: 2326–2333, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mengel M, Chang J, Kayser D, Gwinner W, Schwarz A, Einecke G, Broecker V, Famulski K, de Freitas DG, Guembes-Hidalgo L, Sis B, Haller H, Halloran PF: The molecular phenotype of 6-week protocol biopsies from human renal allografts: Reflections of prior injury but not future course. Am J Transplant 11: 708–718, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stegall MD, Park WD, Larson TS, Gloor JM, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Dean PG, Prieto M, Amer H, Textor S, Schwab T, Cosio FG: The histology of solitary renal allografts at 1 and 5 years after transplantation. Am J Transplant 11: 698–707, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opelz G, Wujciak T, Ritz E: Association of chronic kidney graft failure with recipient blood pressure. Collaborative Transplant Study. Kidney Int 53: 217–222, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Sutherland DE, Mauer M: Sequential renal biopsies in insulin-dependent diabetic patients: Structural factors associated with clinical progression. Kidney Int 48: 1929–1935, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim H, Mauer M: Effect of glycemic control on the expansion of the cortical interstitium in type 1 diabetic renal transplant recipients[Abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 691, 2001 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.