Abstract

We previously reported that the fawn-hooded hypertensive (FHH) rat is a natural Rab38 knockout, supported by a congenic animal (FHH.BN-Rab38) having less proteinuria than FHH animals. Because these congenic animals contain Brown Norway (BN) alleles for five other named genes; however, a causal role for Rab38 in the FHH phenotype remains uncertain. Here, we used transgenic and knockout models to validate Rab38 and to exclude other genes within the 1.5 Mb congenic region from involvement in causing the FHH phenotype. Transgenic rats homozygous for the wild-type Rab38 BN allele on the FHH background exhibited phenotypic rescue, having 43% lower proteinuria and 75% lower albuminuria than nontransgenic FHH littermates. Conversely, knockout of the Rab38 gene on the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic line recapitulated a proteinuric phenotype indistinguishable from the FHH strain. In addition, in cultured proximal tubule LLC-PK1 cells, knockdown of Rab38 mRNA significantly decreased endocytosis of colloidal gold-coupled albumin, supporting the hypothesis that Rab38 modulates proteinuria through effects on tubular re-uptake and not by altering glomerular permeability. Taken together, these findings validate Rab38 as a gene having a causal role in determining the phenotype of the FHH rat, which models hypertension-associated renal disease. Furthermore, our data suggest that Rab38 affects urinary protein excretion via effects in the proximal tubule.

Genome-wide association studies continue to identify regions that influence risk to common disease, such as hypertension, diabetes, and renal failure.1 Affected sibpair and family-based study designs have also identified regions of the human genome relevant to these same traits.2–7 However, these studies fall short of isolating with certainty the causal variant within the linkage disequilibrium or quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with the phenotype, leaving the underlying mechanism of action undefined. Animal models offer a complementary approach to discovery and validation of genotype-phenotype relationships. Reduced genetic complexity, controlled environmental interactions, a host of genome manipulation technologies, and a wealth of comparative pharmacologic and pathophysiologic studies position rat models as powerful tools in the quest from gene identification to translation into clinically actionable insights. The mapping of five QTLs (Rf-1 through Rf-5) linked to the development of proteinuria (urinary protein excretion [UPE]), albuminuria (urinary albumin excretion [UAE]), and focal glomerulosclerosis (FGS) in the fawn-hooded hypertensive (FHH) rat was the first direct genetic evidence of hypertension-associated renal disease.8–10 Syntenic regions to these QTLs in humans have since been implicated in renal failure by multiple investigators.11–13 The Rf-2 locus maps to chromosome 1 and has been shown to play a role in the development of proteinuria in FHH and other rat models of renal disease.14–17 We previously reported that the FHH strain is a natural Rab38 knockout, harboring a G→A mutation that causes a substitution in the start codon (Met→Ile). This mutation ablates RAB38 protein expression and appeared to contribute to the development of UPE and UAE.18 Rab38 is a member of the Rab family of small GTPases, which regulate intracellular vesicle formation and trafficking.19 This GTPase has also been implicated in the storage pool bleeding disorder in FHH and other rat strains.20–22 A mutation in this gene is also responsible for oculocutaneous albinism in FHH, characterized by fawn coat color (instead of black, as seen in Rab38 wild-type rats) and decreased eye pigmentation.18,22 In our previous study, we developed a congenic animal (FHH.BN-Rab38) in which the mutant Rab38 was replaced by a wild-type allele derived from the Brown Norway (BN) strain. FHH.BN-Rab38 rats showed significant improvement in both UPE (40% lower) and UAE (60% lower) compared with FHH.18 These changes were independent of glomerular permeability or BP and suggested that Rab38 affects tubular re-uptake and processing of filtered proteins. However, the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics carry seven other genes (five are named genes) with alleles from BN, as well as Rab38, making it possible that the Rab38 mutation was not causal, even if it was the only coding variant identified between the FHH and FHH.BN-Rab38 strains.18

For this study, we set out to validate Rab38 as the Rf-2 gene by two complementary approaches. First, we tested whether we could rescue the phenotype, defined as reducing UPE and UAE levels in FHH to levels similar to that of FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics, by adding the wild-type allele of Rab38 from BN onto the FHH background using the transposon-mediated transgenesis technique.23 Reciprocally, we disrupted the BN allele of Rab38 in the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic strain using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) targeted mutagenesis to mimic the natural FHH mutation and test whether we could ablate the protective effects of the congenic region on UPE and UAE.

To gain insight into the subcellular mechanisms by which Rab38 may influence proteinuria, we investigated the effect of knocking down the expression of Rab38 on the endocytotic processing of albumin in cultured renal tubular cells. Knockdown of Rab38 in LLC-PK1 cells was achieved via stable transduction with a lentivirus expressing a short hairpin RNA construct (shRNA) targeting the Rab38 mRNA. Cells were evaluated for their ability to uptake colloidal gold-coupled BSA (BSA-gold) by transmission electron microscopy.

Results

Characterization of Tg-Rab38+/+ Transgenic Animals

In our previous work, we identified a mutation in Rab38 that was associated with higher levels of proteinuria in FHH.18 If this variant contributes to the levels of UPE and UAE found in the FHH, then providing the wild-type allele of Rab38 from the BN to the FHH via transgenesis would mimic the protective effect on protein excretion seen in FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics.

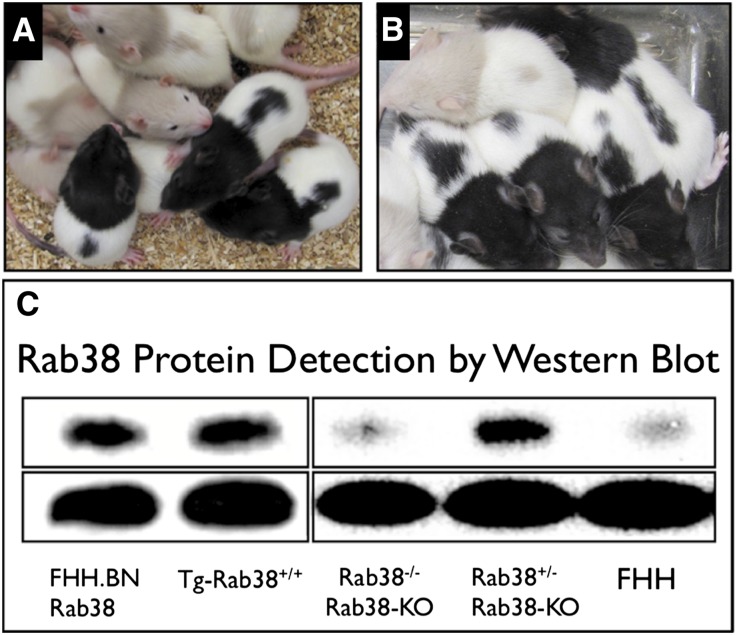

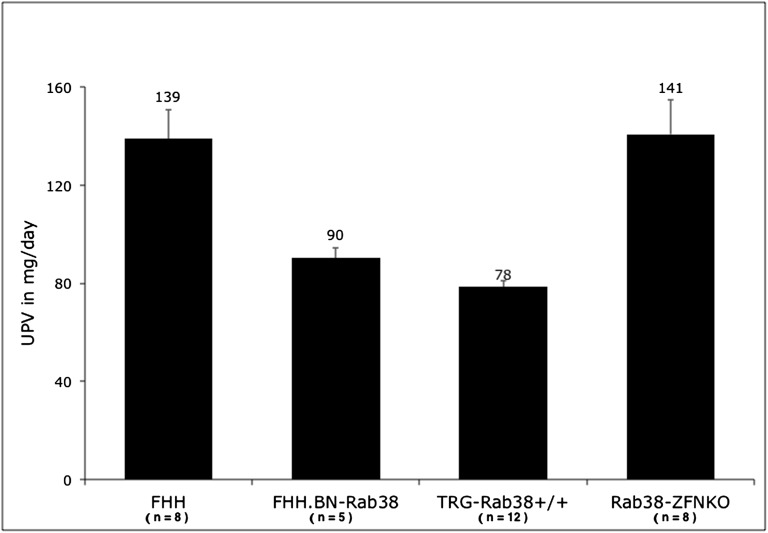

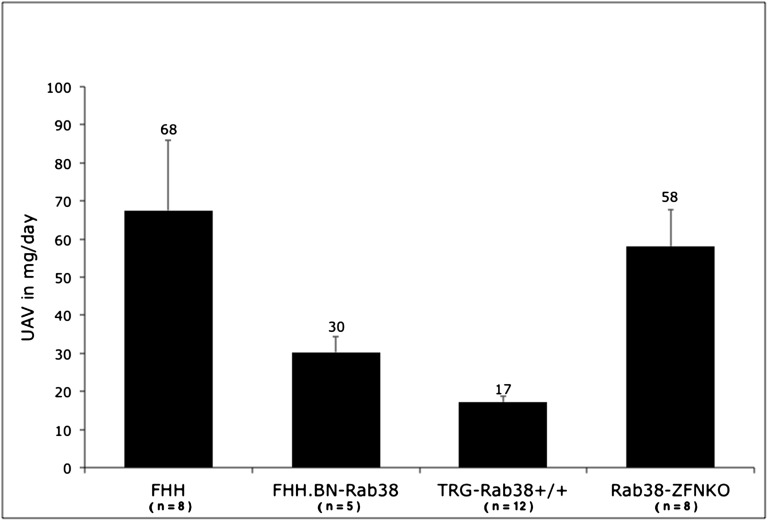

Tg-Rab38+/+ animals carry the wild-type allele that is driven by the ubiquitous chicken-actin-globin (CAG) promoter on a FHH genomic background (Figure 1). Transgenic founders were backcrossed and transgenic siblings intercrossed to generate homozygote animals used in the experiments reported here. In line with our previous observations in the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics,18 restoration of Rab38 expression in Tg-Rab38+/− or Tg-Rab38+/+ corrected the oculocutaneous albinism in FHH (Figure 2A), producing the expected black hood and dark brown eyes as opposed to the fawn hood and ruby eyes seen in FHH. Western blot analysis revealed an immunoreactive band at the apparent molecular weight of RAB38 (27 kD) in whole-kidney homogenates of FHH.BN-Rab38 and Tg-Rab38+/+, but not in FHH (Figure 2C). There was no difference in conscious mean arterial BP between Tg-Rab38+/+ and FHH (BP: 116±3 versus 111±2 mmHg, respectively, P=0.14). The UPE (Figure 3) and UAE (Figure 4) phenotypes were successfully rescued in Tg-Rab38+/+ animals, which presented 43% lower UPE and 75% lower UAE than nontransgenic FHH littermates (UPE: 79±3 mg/d versus 139±12 mg/d, respectively, P<0.001; UAE: 17±1 mg/d versus 68±18 mg/d, respectively, P=0.003).

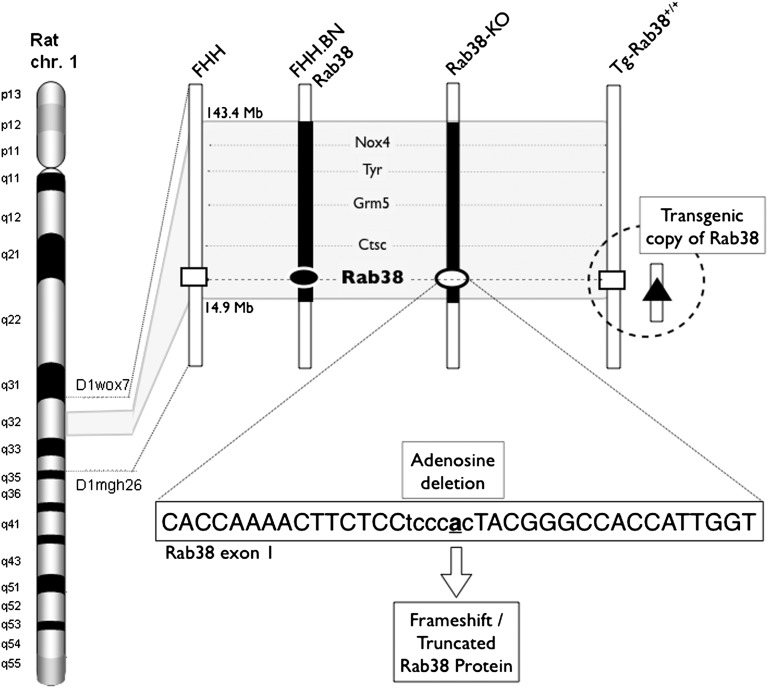

Figure 1.

Genetic makeup of FHH and the three animal models (FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic, Rab38-KO knockout, and Tg-Rab38+/+ transgenic) within the Rf-2 QTL on rat chromosome 1. Five named genes are present within the region (Nox4, Tyr, Grm5, Ctsc, and Rab38). Solid bars indicate BN genome and open bars indicate FHH genome. The congenic animals carry an approximately 1.5 Mb region of the BN genome on the FHH background. Open rectangles indicate FHH Rab38 allele. Solid oval indicates BN Rab38 allele. Solid triangle indicates added transgenic copy of BN Rab38 inserted onto chromosome 14, roughly 13.2 Mbp, and is >100 kbp away from the nearest gene (downstream of Antrx2) as a single copy on the FHH genetic background. Open oval indicates the ZFN-mediated knockout of the Rab38 gene in the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic genetic background. The ZFN target sequence is shown within the text box. Rab38-KO animals carry an adenosine deletion (bold and underlined “a”) that leads to a frameshift and truncation of the RAB38 protein.

Figure 2.

Oculocutaneous albinism and protein expression is affected by Rab38 allele status. (A) Transgenic addition of normal copies of the Rab38 onto the FHH genomic background (fawn hood coat color) corrects the oculocutaneous albinism in Tg-Rab38+/+ animals (black hood coat color). (B) Knockout of Rab38 in the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic background (black hood) recapitulates the pigment disorder of FHH in Rab38-KO animals (fawn hood). (C) Composite image of two representative Western blots of whole-kidney homogenates (gel 1, leftmost two lanes; gel 2, rightmost three lanes). Top row, a band at the apparent molecular mass of Rab38 (27 kD) is detected in the wild-type FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics, Tg-Rab38+/+ transgenics, and heterozygote Rab38-KO (Rab38+/−) knockouts, but not in the FHH strain or homozygote Rab38-KO (Rab38−/−) knockouts. Replacement of the mutant allele (FHH) with the normal (BN) restores RAB38 protein expression in the Tg-Rab38+/+ transgenics. Bottom row, β-actin protein (ACTB) detection is shown as a control for equal loading of the lanes.

Figure 3.

UPE in FHH and Rab38 models. Proteinuria is significantly reduced in the models that harbor normal alleles of Rab38 (FHH.BN-Rab38 and Tg-Rab38+/+) compared with FHH (P<0.05). Disruption of the functional Rab38 alleles in the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic by ZFN in the Rab38-KO model abolishes the protective effect of the congenic region and re-establishes high levels of proteinuria indistinguishable from that of FHH (P=0.92). The number of animals used in each group is indicated under the model name. Numbers above the error bars indicate the mean UPE in milligrams per day. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 4.

UAE in FHH and Rab38 models. Albuminuria is markedly reduced in the Tg-Rab38+/+ compared with FHH (P<0.01). Consistent with our previous observation in FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics, the effect of restored Rab38 in decreasing UAE is more pronounced than that on UAE. Disruption of the functional Rab38 alleles in the Rab38-KO model abolishes the protective effect of the congenic region and recapitulates high UAE levels similar to that of FHH (P=0.65). The number of animals used in each group is indicated under the model name. Numbers above the error bars indicate the mean UAE in milligrams per day. Error bars represent SEM.

Characterization of Rab38-KO Knockout Animals

Congenic FHH.BN-Rab38 rats are >99.99% genetically identical to FHH, except for the introgressed 1.5 Mb region from the BN (Figure 1), and exhibit a marked reduction of UPE and UAE.18 Rab38-KO rats were generated by ZFN-mediated mutagenesis targeting the wild-type Rab38 allele from BN in this FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic model.24 If a mutation in Rab38 is indeed part of the underlying mechanism leading to higher protein excretion in FHH, disruption of the wild-type allele would be expected to ablate the protective effects of the congenic region observed in FHH.BN-Rab38 rats.

Sequencing of a founder animal revealed a single adenosine nucleotide deletion in the spacer region of the target sequence, predicted to cause a frameshift and truncation of the protein (Figure 1). Homozygous congenic Rab38-KO pups from intercrosses of heterozygous parents display a fawn-hooded coat color and ruby eyes in contrast to the heterozygous and wild-type littermates that retained the black coat color and dark eyes (Figure 2B). Kidney extracts of the Rab38-KO heterozygotes (Rab38+/−) showed RAB38 expression at levels comparable with FHH.BN-Rab38, indicating that ablation of a single copy of the gene was not sufficient to achieve a significant effect (Figure 2C). This is consistent with the recessive mode of inheritance of the Rf-2 locus.10,18 In the homozygote Rab38-KO, RAB38 expression levels are similar in migration pattern and intensity to the one seen in FHH, which carries a mutation in the ATG-start site, producing a natural Rab38 knockout.18,22 The remaining shadow band most likely represents cross-reactivity with another highly homologous member of the RAB family.

BP was indistinguishable between FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic and the Rab38-KO (108±3 mmHg versus 111±1 mmHg, respectively, P=0.2). Knockout animals showed an average increase of 55% in UPE and 92% in UAE compared with FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics (UPE: 141±14 mg/d versus 91±4 mg/d, respectively, P<0.05; UAE: 58±10 versus 30±4 mg/d, respectively, P<0.05) (Figures 4 and 5). Importantly, UPE and UAE in rats carrying the Rab38-KO were statistically indistinguishable from the FHH rats (UPE: 141±14 versus 139±12 mg/d, respectively, P=0.92: UPE: 58±10 versus 68±18, respectively, P=0.65). Thus, disruption of Rab38 completely abolished the protective effects of the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic region.

Figure 5.

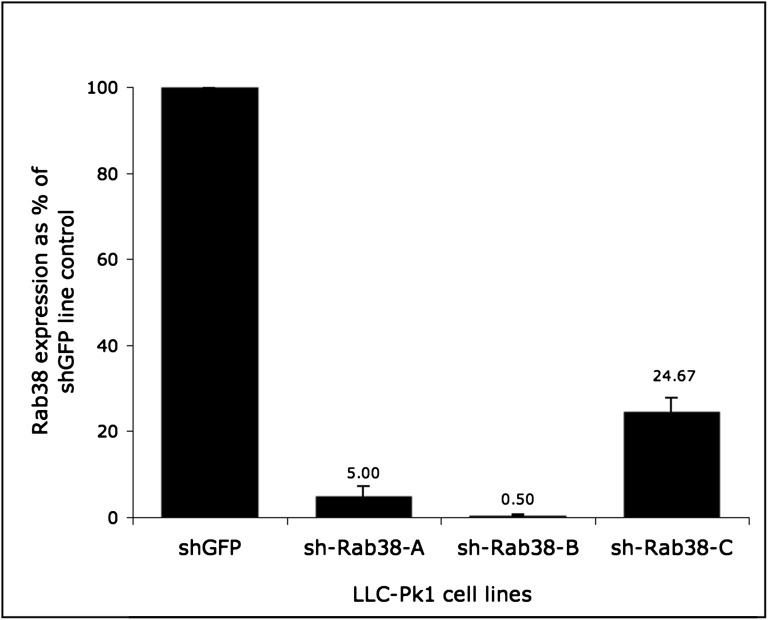

Rab38 expression in LLC-PK1 knockdown cell lines measured by real-time quantitative PCR and shown as a percentage of control. The expression level of the control sh-GFP line is designated as 100%. Rab38 mRNA expression levels in the knockdown cell lines range from 0.5% to about 25%. The sh-Rab38-B line shows the most efficient inhibition (99.5%) and is used in subsequent studies.

BSA-Gold Endocytosis in LLC-PK1 Cells

On the basis of our previous work,18 we sought to investigate if Rab38 influences the absorption of albumin at the level of the proximal tubule cells. To test this question, we used shRNA constructs to knock down Rab38 in LLC-PK1 cells, which are differentiated porcine kidney cells of proximal tubular origin. This cell line possesses characteristics of the proximal tubule such as brush border, Na+-dependent transport systems, alkaline phosphatase, and megalin expression.25,26 LLC-PK1 cells have a well characterized mechanism of protein uptake27,28; therefore, if Rab38 is involved at the level of the proximal tubule, the shRNA-mediated knockdown may affect transport of BSA-gold. We used three distinct shRNA targeting Rab38 (sh-Rab38-A, sh-Rab38-B, and sh-Rab38-C) to generate three stable cell lines, each carrying one of the shRNA constructs.

To assess mRNA inhibition, we compared the three stable Rab38 knockdown LLC-PK1 cell lines with an LLC-PK1 cell line carrying a shRNA targeting green fluorescent protein (GFP) that was used as a control. Rab38 mRNA levels in the knockdown lines ranged from 0.5% to 25% of that of the control line as quantified by real-time quantitative PCR (Figure 5). The sh-Rab38-B line showed the highest rate of inhibition and was selected for subsequent experiments.

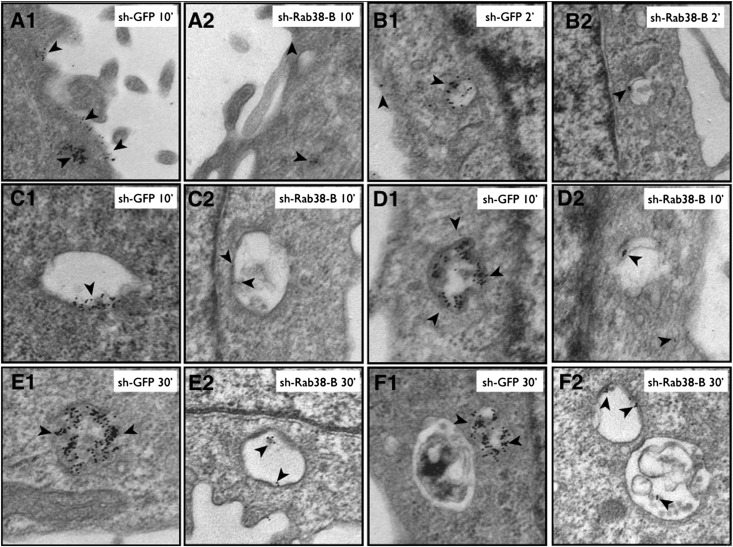

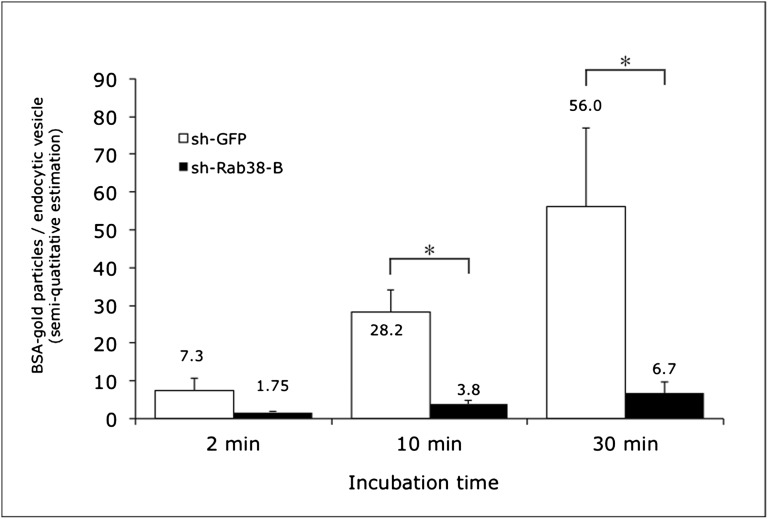

To determine the effect of Rab38 knockdown on protein uptake, sh-GFP control and sh-Rab38-B (99.5% Rab38 knockdown) LLC-PK1 cells were incubated for 2, 10, and 30 minutes with 10 nm BSA-gold and evaluated by electron microscopy. Semi-quantitative analysis of BSA-gold internalization and accumulation in endocytic vesicles and early endosomes showed markedly reduced uptake in sh-Rab38-B cells (Figures 6 and 7). The mean BSA-gold particle/endocytic vesicle ratio was lower in sh-Rab38-B compared with sh-GFP cells at all time points and reached statistical significance at 10 minutes (3.8±1.2 particles per vesicle versus 28.15±5.8 particles per vesicle, P=0.003) and 30 minutes (6.7±2.8 particles per vesicle versus 56±20 particles per vesicle, P=0.04), suggesting that Rab38 contributes normal tubular uptake of filtered proteins (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Representative images showing BSA-gold uptake assayed by transmission electron microscopy. LLC-PK1 cells maintain well differentiated proximal tubule morphology with a well developed brush border (A1 and A2), coated pits, and several small and large endosomes. Cell line sh-Rab38-B carries a shRNA construct targeting Rab38 and the control sh-GFP line carries a construct targeting GFP. Cells are incubated with BSA-gold for increasing intervals and particle uptake is evaluated. Incubation for 10 minutes reveals markedly reduced association of BSA-gold particles with the brush border in Rab38 knockdown cells compared with controls (A2 and A1, respectively, arrowheads). At each additional time point (2–30 minutes), BSA-gold uptake into endosomes at different stages of maturation is also significantly reduced in the knockdown lines (A2, B2, C2, D2, E2, and F2, arrowheads) compared with control cells (A1, B1, C1, D1, E1, and F1, arrowheads).

Figure 7.

Semi-quantitative analysis of BSA-gold uptake assayed by transmission electron microscopy. The number of BSA-gold particles per endocytic vesicle is lower in the sh-Rab38-B cell lined compared with control sh-GFP cells at all time points (2, 10, and 30 minutes). This finding suggests a role for Rab38 in the tubular processing of filtered proteins. Data are shown as average ratios of BSA-gold particles/endocytic vesicles. Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences between cell lines (P<0.05). Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Hypertension-associated renal disease in FHH has been linked to five genomic regions (Rf-1 through Rf-5).8–10,29 We previously demonstrated that the Rf-2 locus accounts for approximately 40% of the difference in UPE and at least 60% of the difference in UAE between FHH and FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics.18 However, despite being >99.99% genetically identical to FHH, FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics carry the BN allele for seven genes (five named), which could not be formally excluded from affecting protein excretion. In this study, we utilized two complementary genomic modification approaches to show direct evidence that Rab38 is the gene within the congenic region which influences the development of UPE and UAE in vivo in FHH rats. Through transgenic replacement, we demonstrated that restoration of Rab38 expression in Tg-Rab38+/+ significantly reduced protein excretion, illustrating that the phenotype can be rescued. The transgenic differs from the parental FHH by carrying two additional copies of wild-type Rab38 from the nonproteinuric BN strain. In the transgenics, the oculocutaneous phenotype was corrected (Figure 2A) and UPE and UAE were 43% and 75% lower than FHH, respectively. Conversely, knockout of the Rab38 gene on the FHH.BN-Rab38 background reversed both the oculocutaneous pigmentation (Figure 2B) and the antiproteinuric effect of the congenic region. Protein excretion in Rab38-KO increased on average 55% (UPE) and 92% (UAE) compared with FHH.BN-Rab38 congenics and was statistically indistinguishable from that of FHH. Changes in UPE and UAE were independent of BP in all genetically modified strains, which was indistinguishable from that of FHH.

Our previous work indicated that the congenic region in FHH.BN-Rab38 does not reduce glomerular permeability or protect from FSGS.18 These observations combined with the lack of change in BP suggest defective proximal tubular protein reabsorption as a potential mechanism contributing to the UPE and UAE in this model. The tubular mechanism of protein endocytosis involves extensive intracellular vesicle formation and trafficking that is partly regulated by small Rab GTPases such as Rab38.19,30 Knockdown of Rab38 in LLC-PK1 porcine proximal tubule cells resulted in markedly diminished internalization and accumulation of BSA-gold particles within endocytic vesicles and early endosomes. This suggests that Rab38 may be indeed necessary for proper tubular re-uptake of filtered proteins and that lack of functional Rab38 in FHH or in Rab38-KO may significantly impair this process, leading to tubular proteinuria. The concept of aberrant vesicular trafficking in tubular cells as the mechanism for the development of proteinuria is supported by evidence derived from several forms of renal disease including Dent’s disease, Lowe syndrome, and some forms of cystinosis, as well as from animal studies.31–40 Defective trafficking of the receptors cubilin and megalin leads to marked proteinuria in the CLC-5 knockout mouse model of Dent’s disease. Of note, at least two Rab proteins (Rab5 and Rab7) are involved in the placement of these receptors at the tubular cell apical membrane.34 Lastly, a rat model that carries the same Rab38 mutant allele as FHH, the Long Evans Cinnamon rat, has a defect in the tubular excretion of phenolsulfonphthalein as a result of altered vesicular trafficking.41 These reports, together with our in vivo observations in FHH, FHH.BN-Rab38, Tg-Rab38+/+, and Rab38-KO and in vitro observations in LLC-PK1 cells, strongly support our hypothesis that lack of functional Rab38 contributes to UPE and UAE likely by altering tubular re-uptake and processing of filtered proteins.

Rab38 may achieve its effect on proteinuria through a number of mechanisms. Fawn-hooded rats have dysfunctional lysosome-related organelles such as platelet dense granules, melanosomes, and alveolar cell lamellar bodies that can be normalized by restoration of Rab38 expression.20,42,43 Abnormal lysosomal function in proximal tubular cells could conceivably diminish the breakdown of filtered proteins. Alternatively, aberrant trafficking could lead to misplacement or redistribution of receptors such as megalin and cubilin, causing decreased protein re-uptake.

In summary, our combined results from three distinct in vivo models validate Rab38 as the Rf-2 gene, which modulates proteinuria and albuminuria in the FHH model of hypertension-associated renal disease. In addition, we show in vitro evidence that Rab38 may affect UPE and UAE at the level of the proximal tubule. We demonstrated that albumin uptake in LLP-PK1 cells is significantly decreased in the absence of Rab38 expression.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that formally assigns a role for Rab38 in renal pathophysiology. Although the exact mechanism of action of Rab38 in protein excretion remains to be elucidated, FHH and our congenic, transgenic, and knockout rats emerge as valuable in vivo models for the study of proteinuria and albuminuria isolated from BP and glomerular damage.

Concise Methods

FHH.BN-Rab38 Congenic Animals

Experiments were performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The official Rat Genome Database (RGD) strain name of the FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic is FHH.BN-(D1Hmgc14-D1Hmgc15)/Mcwi. This strain was developed by marker-assisted selective breeding to carry 1.5 Mb of the BN genome on the FHH background as reported previously.18 Rats were fed standard chow (Purina) and water ad libitum.

Generation of Tg-Rab38+/+ Transgenic Animals

A Sleeping Beauty transposon expressing the wild-type BN (RGD strain: BN/NHsdMcwi) Rab38 cDNA coding sequence under the control of the ubiquitous CAG promoter was injected into FHH (RGD strain: FHH/EurMcwi) embryos with a mRNA source of the SB100× transposase to produce Tg-Rab38+/+ transgenics (RGD strain: FHH-Tg(CAG-Rab38)1Mcwi) on FHH background.23,44 Linker-mediated PCR was used to clone the site(s) of integration of the T2Rab38 transgene. The line was found to harbor a single insertion of the transgene integrated by transposition, also evidenced by Mendelian inheritance after backcross. The transgene insertion was mapped to chromosome 14, roughly 13.2 Mbp, and was more than 100 kbp away from the nearest gene (downstream of Antrx2). Heterozygous animals were intercrossed to establish a homozygous breeding colony used for studies.

Generation of Rab38-KO Knockout Animals

The FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic strain was the progenitor strain for the Rab38 knockout rats (RGD strain: FHH.BN-(D1Hmgc14-D1Hmgc15)/Mcwi-Rab38em1Mcwi−/−) made using a ZFN as previously described.18,24 Briefly, ZFN reagents were designed and assembled by Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) to target the following genomic sequence CACCAAAACTTCTCCtcccacTACGGGCCACCATTGGT in the first exon of Rab38, which we believed would best mimic the ATG-start site mutation found in the FHH. The underlined sequences are the target site recognition sequence for each molecule of the ZFN pair, separated by a 6 bp spacer in lowercase letters. The ZFN mRNA was diluted in microinjection buffer (1 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.4, 0.1 mM EDTA) at a concentration of 10 ng/µl and injected into the pronucleus of newly fertilized FHH.BN-Rab38 (FHH.BN-(D1Hmgc14-D1Hmgc15)/Mcwi) congenic strain embryos. Founder generation biopsy was performed and DNA was extracted as previously described,45 PCR amplified using Rab38_F: 5′-GTAATCGGCGACCTAGGTG-3′ and R: 5′-TCCATTCCCGGAACCTTCAC-3′, and subjected to the Surveyor Nuclease Cel-I assay (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE) as previously described.24 We selected a founder carrying a deletion/truncation of Rab38 for backcrossing. Sibling carriers were identified by genotyping before intercrossing to establish a colony for the studies reported here.

Production of Rab38 shRNA Lentiviral Vectors

Plasmids TRCN0000048183, TRCN0000048184, and TRCN0000048186 and a control vector targeting GFP were from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). For simplicity, we designated these plasmids as sh-Rab38-A, sh-Rab38-B, sh-Rab38-C, and sh-GFP, respectively. Each vector consists of a pLKO.1 backbone harboring a puromycin resistance cassette and a shRNA targeting either human RAB38 or GFP driven by the human U6 promoter (hU6).46 Sequence alignment was performed to determine the degree of homology between human Rab38 and the porcine homolog found in LLC-PK1 cells. The shRNA target sequence of sh-Rab38-B is identical in human and pig. There was one mismatch in each sh-Rab38-A and sh-Rab38-C between pig and human targets. The packaging plasmid psPAX2 and the envelope plasmid pMD2G containing the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein were obtained through the laboratory of Dr. Didier Trono (Lausanne, Switzerland). Lentivirus vectors were produced using a modification of a previously published protocol.47 Briefly, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA) was used to cotransfect the plasmids psPAX2, pMD2G, and sh-Rab38-(A, B, or C) into 293T/17 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 hours. Viral particles were harvested by centrifugation of the cell culture supernatant, filter sterilized, aliquoted, and kept at −80°C until time of use.

Cell Culture and Generation of LLC-PK1 Rab38 Knockdown and Control Cell Lines

Porcine LLC-PK1 proximal tubule cells were from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were grown to a confluent monolayer in DMEM, 10% FBS with penicillin, and streptomycin in 100-mm dishes at 37°C, 5% CO2. Transduction was carried out by overnight incubation in 5 ml of lentiviral particle solution. Starting 48 hours after transduction, cells were selected for stable integration of the shRNA cassette by incubation in 5 μg/ml puromycin. One cell line was generated for each of the constructs (sh-Rab38-A, sh-Rab38-B, sh-Rab38-C, and sh-GFP). Cells were split 1:20 under continuous puromycin selection for a minimum of four passages. The cell line carrying the sh-Rab38-B construct (TRCN0000048184) showed the greatest rate of Rab38 mRNA knockdown (99.5% inhibition) and was used in the BSA-gold uptake experiments.

Rab38 Expression in PK1-Rab38-sh Lines

Rab38 expression was measured by real-time quantitative PCR using SYBR green chemistry as described elsewhere.48 Relative Rab38 transcript abundance was estimated as the average of four measurements per cell line using the ΔΔ Ct method with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a reference gene.49 The average Rab38 expression in the control sh-GFP line was designated as 100%. The average cell line-specific Rab38 expression rate was calculated and plotted relative to the sh-GFP control line. The average inhibition rate for each cell line was calculated by subtracting each cell line’s average expression from that of control sh-GFP line. Primers used to amplify porcine Rab38 (XM_003482585.1) were pigRab38_F: 5′-GCATCAGCCCAGTGTTTA-3′ and pigRab38_R: 5′-GACCAGCAGAGGATGTATTG-3′. Primers for porcine GAPDH (NM_001206359.1) were pigGAPDH_F: 5′-GATCCCGCCAACATCAAA-3′ and pigGAPDH_R: 5′-GGTTCACGCCCATCACAA-3′.

Evaluation of BSA-Gold Endocytosis by Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy-grade 10 nm BSA-gold was from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA). The BSA-gold particle solution was dialyzed against 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) to remove azide preservative and suspended in the same buffer to a final absorbance of 1.5 at 525 nm. Cells from line sh-Rab38-B were seeded at 3×106 cells per well in six-well culture plates and allowed to adhere and form a confluent monolayer overnight. Culture medium was removed the following day and cells were incubated in 1 ml of prewarmed (37°C) BSA-gold solution for 2 minutes, 10 minutes, and 30 minutes followed by three washes in 3 ml warm PBS and immediate fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Sheets of cells were mechanically detached, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a series of graded ethanols, and embedded in epoxy resin. Thin sections were examined with a Hitachi 600 transmission electron microscope (Nissan Sangyo, San Jose, CA) operated at 75 kV. Albumin uptake was estimated in a semi-quantitative fashion by counting the number of BSA-gold containing vesicles (early endosomes and endocytic vesicles) in five random electron microscopic fields (4.4 mm2) per time point and calculating the gold particle per vesicle ratio. Data are summarized as the ratio of mean BSA-gold particles per endocytic vesicles. Between-group difference was performed by single-factor ANOVA.

Urinary Protein/Albumin Excretion

Rats aged 12 weeks were placed in metabolic cages for 24 hours, after which urine was collected in two consecutive 24-hour periods. Total protein was measured by the Weichselbaum’s Biuret method.50 Albumin excretion was measured with the AB580 assay.51 Results are reported as the average of the two collection days.

BP Measurements

BP was measured directly, in conscious rats, by catheterization of the femoral artery coupled to telemetry as previously reported.52 Briefly, 13-week-old rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and a BP transmitter (PA-C40, DSI) was implanted subcutaneously with the catheter tip secured in the abdominal aorta via the femoral artery. After the 3-day recovery period, BP was measured by radio telemetry in conscious freely moving animals for 3 days, for 3 hours per day. Mean arterial pressure was averaged over the recorded segment.

Western Immunoblotting

Proteins from whole-kidney homogenates of 12-week-old FHH, FHH.BN-Rab38 congenic, Tg-RAB38+/+, and Rab38-KO rats were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and probed with a polyclonal mouse anti-rat RAB38 antibody as previously described.18 Detection of β-actin was used as a control.

Statistical Analyses

BP, UPE, and UAE in all groups were compared by single-factor ANOVA and all pairwise multiple comparisons were performed by the Newman–Keuls method. Data are presented as mean and SEM. Five to 12 animals per experimental group were studied. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. W. Wells (Medical College of Wisconsin Electron Microscopy Core Facility) for assistance with transmission electron microscopy, as well as Rebecca Schilling, Matt Hoffman, Allison Zappa, Nadia Barreto, Jaime Foeckler, and Shawn Kalloway for technical assistance.

This study was performed with financial support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI-5R01HL069321) to H.J.J.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Present address: Dr. Artur Rangel-Filho, Department of Pathology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida.

References

- 1.McCarthy MI, Hirschhorn JN: Genome-wide association studies: Potential next steps on a genetic journey. Hum Mol Genet 17[R2]: R156–R165, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lander ES, Schork NJ: Genetic dissection of complex traits. Science 265: 2037–2048, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schork NJ: Genetics of complex disease: Approaches, problems, and solutions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: S103–S109, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pattaro C, Köttgen A, Teumer A, Garnaas M, Böger CA, Fuchsberger C, Olden M, Chen M-H, Tin A, Taliun D, Li M, Gao X, Gorski M, Yang Q, Hundertmark C, Foster MC, O’Seaghdha CM, Glazer N, Isaacs A, Liu C-T, Smith AV, O’Connell JR, Struchalin M, Tanaka T, Li G, Johnson AD, Gierman HJ, Feitosa M, Hwang S-J, Atkinson EJ, Lohman K, Cornelis MC, Johansson Å, Tönjes A, Dehghan A, Chouraki V, Holliday EG, Sorice R, Kutalik Z, Lehtimäki T, Esko T, Deshmukh H, Ulivi S, Chu AY, Murgia F, Trompet S, Imboden M, Kollerits B, Pistis G, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, Mitchell BD, Boerwinkle E, Schmidt H, Cavalieri M, Rao M, Hu FB, Demirkan A, Oostra BA, de Andrade M, Turner ST, Ding J, Andrews JS, Freedman BI, Koenig W, Illig T, Döring A, Wichmann H-E, Kolcic I, Zemunik T, Boban M, Minelli C, Wheeler HE, Igl W, Zaboli G, Wild SH, Wright AF, Campbell H, Ellinghaus D, Nöthlings U, Jacobs G, Biffar R, Endlich K, Ernst F, Homuth G, Kroemer HK, Nauck M, Stracke S, Völker U, Völzke H, Kovacs P, Stumvoll M, Mägi R, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Rivadeneira F, Aulchenko YS, Polasek O, Hastie N, Vitart V, Helmer C, Wang JJ, Ruggiero D, Bergmann S, Kähönen M, Viikari J, Nikopensius T, Province M, Ketkar S, Colhoun H, Doney A, Robino A, Giulianini F, Krämer BK, Portas L, Ford I, Buckley BM, Adam M, Thun G-A, Paulweber B, Haun M, Sala C, Metzger M, Mitchell P, Ciullo M, Kim SK, Vollenweider P, Raitakari O, Metspalu A, Palmer C, Gasparini P, Pirastu M, Jukema JW, Probst-Hensch NM, Kronenberg F, Toniolo D, Gudnason V, Shuldiner AR, Coresh J, Schmidt R, Ferrucci L, Siscovick DS, van Duijn CM, Borecki I, Kardia SLR, Liu Y, Curhan GC, Rudan I, Gyllensten U, Wilson JF, Franke A, Pramstaller PP, Rettig R, Prokopenko I, Witteman JCM, Hayward C, Ridker P, Parsa A, Bochud M, Heid IM, Goessling W, Chasman DI, Kao WHL, Fox CS, CARDIoGRAM Consortium. ICBP Consortium. CARe Consortium. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) : Genome-wide association and functional follow-up reveals new loci for kidney function. PLoS Genet 8: e1002584, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adeyemo A, Gerry N, Chen G, Herbert A, Doumatey A, Huang H, Zhou J, Lashley K, Chen Y, Christman M, Rotimi C: A genome-wide association study of hypertension and blood pressure in African Americans. PLoS Genet 5: e1000564, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J, Bradfield JP, Zhang H, Annaiah K, Wang K, Kim CE, Glessner JT, Frackelton EC, Otieno FG, Doran J, Thomas KA, Garris M, Hou C, Chiavacci RM, Li M, Berkowitz RI, Hakonarson H, Grant SFA: Examination of all type 2 diabetes GWAS loci reveals HHEX-IDE as a locus influencing pediatric BMI. Diabetes 59: 751–755, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böger CA, Gorski M, Li M, Hoffmann MM, Huang C, Yang Q, Teumer A, Krane V, O’Seaghdha CM, Kutalik Z, Wichmann H-E, Haak T, Boes E, Coassin S, Coresh J, Kollerits B, Haun M, Paulweber B, Köttgen A, Li G, Shlipak MG, Powe N, Hwang S-J, Dehghan A, Rivadeneira F, Uitterlinden A, Hofman A, Beckmann JS, Krämer BK, Witteman J, Bochud M, Siscovick D, Rettig R, Kronenberg F, Wanner C, Thadhani RI, Heid IM, Fox CS, Kao WH, CKDGen Consortium : Association of eGFR-related loci identified by GWAS with incident CKD and ESRD. PLoS Genet 7: e1002292, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DM, Provoost AP, Daly MJ, Lander ES, Jacob HJ: Renal disease susceptibility and hypertension are under independent genetic control in the fawn-hooded rat. Nat Genet 12: 44–51, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DM, Van Dokkum RP, Korte MR, McLauglin MG, Shiozawa M, Jacob HJ, Provoost AP: Genetic control of susceptibility for renal damage in hypertensive fawn-hooded rats. Ren Fail 20: 407–411, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiozawa M, Provoost AP, van Dokkum RP, Majewski RR, Jacob HJ: Evidence of gene-gene interactions in the genetic susceptibility to renal impairment after unilateral nephrectomy. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2068–2078, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman BI, Rich SS, Yu H, Roh BH, Bowden DW: Linkage heterogeneity of end-stage renal disease on human chromosome 10. Kidney Int 62: 770–774, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman BI: End-stage renal failure in African Americans: Insights in kidney disease susceptibility. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 198–200, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt SC, Hasstedt SJ, Coon H, Camp NJ, Cawthon RM, Wu LL, Hopkins PN: Linkage of creatinine clearance to chromosome 10 in Utah pedigrees replicates a locus for end-stage renal disease in humans and renal failure in the fawn-hooded rat. Kidney Int 62: 1143–1148, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz A, Litfin A, Kossmehl P, Kreutz R: Genetic dissection of increased urinary albumin excretion in the munich wistar frömter rat. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2706–2714, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz A, Standke D, Kovacevic L, Mostler M, Kossmehl P, Stoll M, Kreutz R: A major gene locus links early onset albuminuria with renal interstitial fibrosis in the MWF rat with polygenetic albuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3081–3089, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Lezin E, Griffin KA, Picken M, Churchill MC, Churchill PC, Kurtz TW, Liu W, Wang N, Kren V, Zidek V, Pravenec M, Bidani AK: Genetic isolation of a chromosome 1 region affecting susceptibility to hypertension-induced renal damage in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 34: 187–191, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yagil C, Sapojnikov M, Katni G, Ilan Z, Zangen SW, Rosenmann E, Yagil Y: Proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis in the Sabra genetic rat model of salt susceptibility. Physiol Genomics 9: 167–178, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rangel-Filho A, Sharma M, Datta YH, Moreno C, Roman RJ, Iwamoto Y, Provoost AP, Lazar J, Jacob HJ: RF-2 gene modulates proteinuria and albuminuria independently of changes in glomerular permeability in the fawn-hooded hypertensive rat. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 852–856, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira-Leal JB, Seabra MC: Evolution of the Rab family of small GTP-binding proteins. J Mol Biol 313: 889–901, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datta YH, Wu FC, Dumas PC, Rangel-Filho A, Datta MW, Ning G, Cooley BC, Majewski RR, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ: Genetic mapping and characterization of the bleeding disorder in the fawn-hooded hypertensive rat. Thromb Haemost 89: 1031–1042, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loftus SK, Larson DM, Baxter LL, Antonellis A, Chen Y, Wu X, Jiang Y, Bittner M, Hammer JA, 3rd, Pavan WJ: Mutation of melanosome protein RAB38 in chocolate mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 4471–4476, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oiso N, Riddle SR, Serikawa T, Kuramoto T, Spritz RA: The rat Ruby ( R) locus is Rab38: Identical mutations in Fawn-hooded and Tester-Moriyama rats derived from an ancestral Long Evans rat sub-strain. Mamm Genome 15: 307–314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mátés L, Chuah MKL, Belay E, Jerchow B, Manoj N, Acosta-Sanchez A, Grzela DP, Schmitt A, Becker K, Matrai J, Ma L, Samara-Kuko E, Gysemans C, Pryputniewicz D, Miskey C, Fletcher B, VandenDriessche T, Ivics Z, Izsvák Z: Molecular evolution of a novel hyperactive Sleeping Beauty transposase enables robust stable gene transfer in vertebrates. Nat Genet 41: 753–761, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, Zeitler B, Miller JC, Choi VM, Jenkins SS, Wood A, Cui X, Meng X, Vincent A, Lam S, Michalkiewicz M, Schilling R, Foeckler J, Kalloway S, Weiler H, Ménoret S, Anegon I, Davis GD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jacob HJ, Buelow R: Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases. Science 325: 433, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hull RN, Cherry WR, Weaver GW: The origin and characteristics of a pig kidney cell strain, LLC-PK. In Vitro 12: 670–677, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen R, Birn H, Moestrup SK, Nielsen M, Verroust P, Christensen EI: Characterization of a kidney proximal tubule cell line, LLC-PK1, expressing endocytotic active megalin. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1767–1776, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishibashi F: High glucose reduces albumin uptake in cultured proximal tubular cells (LLC-PK1). Diabetes Res Clin Pract 65: 217–225, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caruso-Neves C, Kwon S-H, Guggino WB: Albumin endocytosis in proximal tubule cells is modulated by angiotensin II through an AT2 receptor-mediated protein kinase B activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 17513–17518, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kriz W, Hosser H, Hähnel B, Gretz N, Provoost AP: From segmental glomerulosclerosis to total nephron degeneration and interstitial fibrosis: A histopathological study in rat models and human glomerulopathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2781–2798, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duclos S, Corsini R, Desjardins M: Remodeling of endosomes during lysosome biogenesis involves ‘kiss and run’ fusion events regulated by rab5. J Cell Sci 116: 907–918, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weyer K, Storm T, Shan J, Vainio S, Kozyraki R, Verroust PJ, Christensen EI, Nielsen R: Mouse model of proximal tubule endocytic dysfunction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3446–3451, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theilig F, Kriz W, Jerichow T, Schrade P, Hähnel B, Willnow T, Le Hir M, Bachmann S: Abrogation of protein uptake through megalin-deficient proximal tubules does not safeguard against tubulointerstitial injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1824–1834, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carr G, Simmons N, Sayer J: A role for CBS domain 2 in trafficking of chloride channel CLC-5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 310: 600–605, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen EI, Devuyst O, Dom G, Nielsen R, Van der Smissen P, Verroust P, Leruth M, Guggino WB, Courtoy PJ: Loss of chloride channel ClC-5 impairs endocytosis by defective trafficking of megalin and cubilin in kidney proximal tubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 8472–8477, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Camilli P, Emr SD, McPherson PS, Novick P: Phosphoinositides as regulators in membrane traffic. Science 271: 1533–1539, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devonald MAJ, Karet FE: Renal epithelial traffic jams and one-way streets. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1370–1381, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faucherre A, Desbois P, Satre V, Lunardi J, Dorseuil O, Gacon G: Lowe syndrome protein OCRL1 interacts with Rac GTPase in the trans-Golgi network. Hum Mol Genet 12: 2449–2456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalatzis V, Cohen-Solal L, Cordier B, Frishberg Y, Kemper M, Nuutinen EM, Legrand E, Cochat P, Antignac C: Identification of 14 novel CTNS mutations and characterization of seven splice site mutations associated with cystinosis. Hum Mutat 20: 439–446, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shotelersuk V, Larson D, Anikster Y, McDowell G, Lemons R, Bernardini I, Guo J, Thoene J, Gahl WA: CTNS mutations in an American-based population of cystinosis patients. Am J Hum Genet 63: 1352–1362, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suchy SF, Olivos-Glander IM, Nussabaum RL: Lowe syndrome, a deficiency of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 5-phosphatase in the Golgi apparatus. Hum Mol Genet 4: 2245–2250, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itagaki S, Shimamoto S, Hirano T, Iseki K, Sugawara M, Nishimura S, Fujimoto M, Kobayashi M, Miyazaki K: Comparison of urinary excretion of phenolsulfonphthalein in an animal model for Wilson’s disease (Long-Evans Cinnamon rats) with that in normal Wistar rats: Involvement of primary active organic anion transporter. J Pharm Pharm Sci 7: 227–234, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ninkovic I, White JG, Rangel-Filho A, Datta YH: The role of Rab38 in platelet dense granule defects. J Thromb Haemost 6: 2143–2151, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Yu K, Robert KW, DeBolt KM, Hong N, Tao J-Q, Fukuda M, Fisher AB, Huang S: Rab38 targets to lamellar bodies and normalizes their sizes in lung alveolar type II epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L461–L477, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J: Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108: 193–199, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreno C, Kaldunski ML, Wang T, Roman RJ, Greene AS, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW, Jr: Multiple blood pressure loci on rat chromosome 13 attenuate development of hypertension in the Dahl S hypertensive rat. Physiol Genomics 31: 228–235, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moffat J, Grueneberg DA, Yang X, Kim SY, Kloepfer AM, Hinkle G, Piqani B, Eisenhaure TM, Luo B, Grenier JK, Carpenter AE, Foo SY, Stewart SA, Stockwell BR, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM, Root DE: A lentiviral RNAi library for human and mouse genes applied to an arrayed viral high-content screen. Cell 124: 1283–1298, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karolewski BA, Watson DJ, Parente MK, Wolfe JH: Comparison of transfection conditions for a lentivirus vector produced in large volumes. Hum Gene Ther 14: 1287–1296, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison J, Knoll K, Hessner MJ, Liang M: Effect of high glucose on gene expression in mesangial cells: Upregulation of the thiol pathway is an adaptational response. Physiol Genomics 17: 271–282, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winer J, Jung CK, Shackel I, Williams PM: Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal Biochem 270: 41–49, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weichselbaum TE: An accurate and rapid method for the determination of proteins in small amounts of blood serum and plasma. Am J Clin Pathol 10: 40–49, 1946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler MA, Meinitzer A, Wolfbeis OS: Albumin blue 580 fluorescence assay for albumin. Anal Biochem 248: 180–182, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno C, Williams JM, Lu L, Liang M, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW, Jr, Roman RJ: Narrowing a region on rat chromosome 13 that protects against hypertension in Dahl SS-13BN congenic strains. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1530–H1535, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]