Abstract

Patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) commonly suffer chronic respiratory infections, although systemic dissemination is relatively rare. Acute bacterial prostatitis presents dramatically and is believed to be mostly caused by local migration (with or without instrumentation) of the lower urinary tract and presents with a predictable microbial etiology. We report a case of a 26-year-old man presenting with acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacterial prostatitis due to hematogenous propagation from a chronic pulmonary infection.

Introduction

Acute bacterial prostatitis is a urologic emergency that commonly presents with severe voiding symptoms and pelvic pain, and may be complicated by hemodynamic instability and sepsis.1 Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common, fatal, inherited disease of Caucasians. It is a multisystem disease primarily affecting the respiratory, digestive and reproductive systems and is characterized by chronic pulmonary infection. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a relatively common organism in CF-related pulmonary infection and is seldom eradicated, although extrapulmonary spread of chronic infection in immunocompetent CF patients is rare.2–4

We report a case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia and prostatitis in an adult man with CF who was awaiting combined lung-liver transplantation.

Case report

A 26-year-old male with CF, homozygous for the delta F508 mutation, was admitted with a 1-week history of fever, nausea and vomiting in the setting of severe dysuria and penile discharge. He was known to be chronically infected with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with baseline FEV 1 of 1.8 L (47% predicted). His medical history was significant for pancreatic insufficiency, CF-related diabetes (CFRD) and CF-related liver disease, awaiting combined lung-liver transplantation. He had been hospitalized 3 months earlier with an exacerbation of pulmonary symptoms. The patient was not sexually active, and had no history of sexually transmitted infections. He was on chronic antimicrobial therapy (inhaled colistin and oral azithromycin), as well as inhaled salbutamol, inhaled corticosteroids, dornase alfa, pancreatic enzymes, domperidone, omeprazole, PEG 3350, multivitamins including Vitamins D and K, insulin, ursodeoxycolic acid, furosemide and amilioride. He had an allergy to floroquinolones.

On admission, he was febrile (38.8°C). His blood pressure was 110/80, heart rate 88 bpm, respiratory rate 22. Oxygen saturation was 92% on room air. Cardiorespiratory examination revealed bilateral crackles, with normal heart sounds. His abdomen was distended, but non-tender with evidence of splenomegaly. No costovertebral angle tenderness was present. Digital rectal examination revealed a very tender prostate. Admission laboratory tests revealed a leukocyte count of 7.6. Renal function and electrolytes were normal. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and blood. Chest radiograph revealed chronic bronchiectatic changes with no new infiltrates. He was initially started on empiric intravenous ceftriaxone for presumed urosepsis. Urine, blood and sputum cultures were taken prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy.

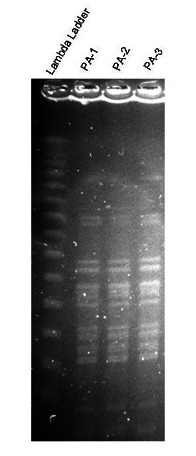

The patient’s fever and dysuria improved on antimicrobial therapy. A pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an enlarged prostate with periprostatic stranding reported as suspicious for prostatitis (Fig. 1). Sputum, blood and urine cultures showed a growing a mucoid strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Urologic consultation confirmed the diagnosis of acute bacterial prostatitis. All isolates were sent for genotyping and were identical on pulsed gel field electrophoresis (Fig. 2). Due to the diagnosis of prostatitis, he was ruled temporarily ineligible for transplant until he completed his antibiotic therapy. Based on culture results, he was treated with intravenous (IV) piperacillin/tazobactam which was subsequently changed to IV ceftazidime due to adverse side effects. He completed a total 8-week course of IV antibiotics for prostatitis. Repeat urine, semen and blood cultures after treatment were negative. He was re-listed for combined transplantation in stable condition with no recurrence of symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Non-contrast computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing enlarged prostate gland and periprostatic inflammation.

Fig. 2.

Pulsed gel field electrophoresis of sputum, blood and urine samples showing same strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first published case of Pseudomonas prostatitis in an adult with CF. Prostatitis has been reported to occur in 10% to 14% of men of all ages and ethnicities.5,6 It is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and physical examination. Acute bacterial prostatitis is classified as Type I prostatitis by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).7 Though its incidence is estimated at only 0.02% of all diagnosed cases of prostatitis, acute bacterial prostatitis represents a urologic emergency that requires the immediate institution of IV antibiotics, and may present with systemic symptoms and hemodynamic instability.1

Previous studies have identified risk factors for the development of prostatitis. These risk factors include benign prostatic hyperplasia, frequent sexual activity, prolonged sexual abstinence, sexually transmitted infections, HIV trauma, stress or transrectal prostate biopsy.5,6,8–10 Typically, entry of microorganisms occurs via the urethra into the prostatic ducts due to direct migration or with intraprostatic reflux of urine.11,12 Usual therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics for 6 weeks; however, in this case, a longer duration was advised.5,11–13 Acute bacterial prostatitis is most often associated with E. coli or Staphylococcus infection, although several other organisms have been reported.1Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute prostatitis has been rarely reported, and has occurred in the setting of poorly controlled HIV with indwelling catheter, frequent intercourse in a hot tub and prostate-cutaneous fistula.14–16

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a predominant pathogen associated with chronic pulmonary infection and mortality in CF.17 Extrapulmonary spread of infection is quite rare, likely owing to enhanced immune complex formation and reticuloendothelial clearance in CF patients.3,4 However, there have been case reports of extrapulmonary spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in immunocompetent CF patients chronically infected with the mucoid strain of this organism with bacteremia, endopthalmitis and pericarditis.18–21 In most cases, patients had poor outcomes, ranging from enucleation to death, despite prompt diagnosis and treatment for their extrapulmonary infections. A common element in these cases was diabetes, the use of steroids or both, that may have affected their immune response and containment of pulmonary infection. Our patient with Pseudomonas aeruginosa prostatitis suffered from CF-related diabetes.

Conclusion

Hematogenous bacterial seeding of the prostate and extra-pulmonary spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are rare events that both occurred in this patient. These are management issues for the CF patient and the acute prostatitis patient. Increased life expectancy in modern CF patients may introduce other comorbidities that affect immune function and proclivity towards extrapulmonary spread of infection. In the patient presenting with classic symptoms of acute bacterial prostatitis, extragenital risk factors must be included in the differential of etiologies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Benway BM, Moon TD. Bacterial Prostatitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantzouranis EC, Rosen FS, Colten HR. Reticuloendothelial clearance in cystic fibrosis and other inflammatory lung disease. N Eng J Med. 1988;319:338–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808113190604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss RB, Lewiston NJ. Immune complexes and humoral responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1980;121:23–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naber KG. Management of bacterial prostatitis: What’s new? BJU Int. 2008;101S:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieger JN, Lee SWH, Jeon J, et al. Epidemiology of Prostatitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31S:S85–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Jr, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallner LP, Clemens JQ, Sarma AV. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Prostatitis in African American Men: The Flint Mens Health Study. Prostate. 2009;69:24–32. doi: 10.1002/pros.20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam RK, Saskin R, Lee Y, et al. Increasing hospital admission rates for urologic complications after transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2010;183:963–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leport C, Rousseau F, Perronne C, et al. Bacterial prostatitis in patients infected with the human immu-nodeficiency virus. J Urol. 1989;141:334–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipsky BA. Urinary tract infections in men. Ann Int Med. 1989;110:138. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-2-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orland SM, Hanno PM, Wein AJ. Prostatitis, prostatosis, and prostatodynia. Urology. 1985;25:439. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kravchick S, Cytron S, Agulansky L, et al. Acute prostatitis in middle-aged men: a prospective study. BJU Int. 2004;93:93–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerin F, Henegar C, Spiridon G, et al. Bacterial prostatitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa harbouring the blaVIM-2 metallo-{beta}-lactamase gene from Saudi Arabia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:601–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dulabon LM, LaSpina M, Riddell SW, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute prostatitis and urosepsis after sexual relations in a hot tub. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1607–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02376-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felipetto R, Viganò L, Cecchi M, et al. Use of fibrin sealant in the treatment of prostatic cutaneous fistula in a case of Pseudomonas prostatitis. Int Urol Nephrol. 1995;27:563–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02564742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoiby N. Recent advances in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in Cystic Fibrosis. BMC Med. 2011;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coffey MJ, Keogan MT, Fitzgerald MX. Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicemia in a young adult with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 1990;84:167–8. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(08)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisner AM, Chart H, Bush A, et al. Detection of antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in serum and oral fluid from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:670–4. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motley W, Augsburger JJ, Hutchins RK, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa endogenous endopthal-mitis with choroidal abcess in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Retina. 2005;25:202–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altemeir WA, Tonelli MR, Aitken ML. Pseudomonal Pericarditis Complicating Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:62–4. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199901)27:1<62::AID-PPUL12>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]