Abstract

We have identified a Crp/Fnr-like transcriptional regulator of Streptococcus pyogenes that when inactivated attenuates virulence. The gene, named srv for streptococcal regulator of virulence, encodes a 240-amino-acid protein with 53% amino acid similarity to PrfA, a transcriptional activator of virulence in Listeria monocytogenes.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is a gram-positive pathogen that is the causative agent of numerous human infections including pharyngitis, a toxic shock syndrome, and necrotizing fasciitis. In addition, the organism is responsible for the postinfectious sequelae acute rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis (1, 7, 26). The only known reservoir of GAS is humans, and the organism is generally disseminated by individuals with symptomatic infection of the mucous membranes or skin, although asymptomatic carriers can transmit the pathogen (7). Thus, rather than exploit a singular niche, GAS has evolved to colonize and disseminate within several distinct anatomical sites of the human host. Such versatility requires the ability to coordinately regulate the expression and production of numerous factors in response to host and environmental signals. Analysis of available GAS genome sequences has revealed a complex regulatory network in GAS, including 13 putative two-component regulatory systems and more than 100 additional possible regulators (11). While the vast majority of these genes remain uncharacterized, the influence of a subset of these GAS regulators is likely to be far-reaching. For example, a recent genome scale analysis indicated that the two-component regulatory system CovRS (CsrRS) directly or indirectly alters the transcription of 15% of the GAS genome (11). Furthermore, the multiple gene regulator Mga has been associated with an array of GAS disease processes such as colonization, invasion, and evasion of the host immune response (15, 18, 23, 27).

A recent investigation of four genomes of GAS (serotypes M1, M3, M5, and M18) (30) identified another putative regulator of GAS. A BLASTP analysis indicated that the 240-amino-acid protein SPy1857 (referred to here as Srv), was homologous to positive regulatory factor A (PrfA), a transcriptional regulator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes (30). It was noted that spy1857 was highly conserved in 37 geographically and phylogenetically diverse GAS strains and that transcription of spy1857 increased by 2.32-fold in a serotype M1 strain lacking mga (30). Taken together, these findings suggested that SPy1857 might play a role in GAS gene regulation. However, the original study was focused on the investigation of putative extracellular proteins, and SPy1857 was not further examined.

PrfA is a member of the Crp/Fnr family of transcriptional regulators, so named for the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (Crp) and the fumarate and nitrate reduction regulator (FNR) of Escherichia coli (17). The basic structural features of this protein family are represented in Crp. These include an N-terminal region consisting of short β-sheets separated by conserved glycine residues (β-roll structures) which form a sensory or allosteric domain (3, 9, 12, 16, 36). The C terminus contains a helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif implicated in DNA binding to a symmetric consensus sequence located upstream of the transcriptional start site (−40 to −200 bp) of regulated genes (3, 9, 12, 16, 36). The best-studied gram-positive member of this protein family is PrfA. PrfA has well-defined N-terminal β-roll structures and a C-terminal HTH motif which binds to a 14-bp symmetric sequence (PrfA box) TTAACANNTGTTAA (where N is an unspecified nucleotide) (10). A recent microarray analysis indicates that PrfA directly or indirectly influences the transcription of 73 L. monocytogenes genes under a variety of conditions (25). Notably, PrfA regulates the expression of most of the known virulence genes of L. monocytogenes, including the virulence gene cluster (prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, and plcB), and several members of the internalin family of proteins (4, 20, 25, 34).

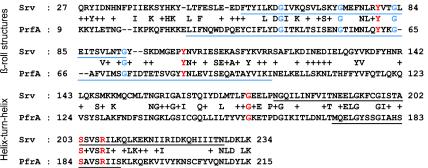

Given the critical role of PrfA in L. monocytogenes virulence, we sought to identify putative structural similarities encoded by srv. Analysis of the inferred amino acid sequence with PredictProtein (http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu) identified four N-terminal β-sheets separated by glycine residues which are predicted to form β-roll structures (Fig. 1). Pairwise sequence alignment of Srv with PrfA indicated that this region overlapped with the identified β-roll structures in PrfA (Fig. 1). The glycine residues which provide the proper spacing of the N-terminal structure are conserved between Srv and PrfA (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Pairwise alignment of the amino acid sequence of GAS Srv and L. monocytogenes PrfA. The sequences are 27% identical and 53% similar over the residues shown. The putative HTH domains of Srv and PrfA are underlined in black. The N-terminal β-roll structures of Srv and PrfA are underlined in blue. The conserved glycine residues separating the β-sheets, thereby allowing the formation of the β-roll structures, are highlighted in blue. Amino acid residues which are required for full activity of PrfA, and are conserved in Srv, are highlighted in red. Srv structural predictions were determined with PredictProtein (http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information Conserved Domain Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/).

PredictProtein analysis and a search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information Conserved Domain Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/) also indicated the presence of a C-terminal HTH motif characteristic of Crp/Fnr proteins (score, 45.0; E value, 7e-06). The two HTH motifs overlap in a pairwise sequence alignment, although the HTH motif of Srv is predicted to be 30 amino acid residues longer (Fig. 1).

Five specific amino acid residues which have been shown in L. monocytogenes to be critical for full function of PrfA are conserved in Srv from a serotype M1 strain (Fig. 1) (13, 33, 35). The residues Y80, Y102, S203, and R207 match PrfA residues Y62, Y83, S184, and R188 in the pairwise sequence alignment, respectively. Amino acid substitutions at three of these positions (Y62, Y83, and R188) lead to decreased PrfA transcriptional activation, while a replacement at S184 alters PrfA binding to the DNA recognition sequence (13, 33). PrfA E77K and G155S mutations lead to increased expression of PrfA-dependent genes (35). PrfA G155 is conserved in Srv (Srv G174), while the residue corresponding to PrfA E77 is K96. To determine if these residues are conserved across multiple strains of GAS, we conducted a multiple sequence alignment of 12 phylogenetically diverse strains which represent 12 M-protein serotypes that commonly cause pharyngitis, rheumatic fever, skin infections, and invasive episodes. All five residues were conserved in the strains examined. Overall, only a single amino acid substitution was identified in a serotype M6 strain, suggesting the action of purifying selection. The functional importance of these residues in Srv is under investigation.

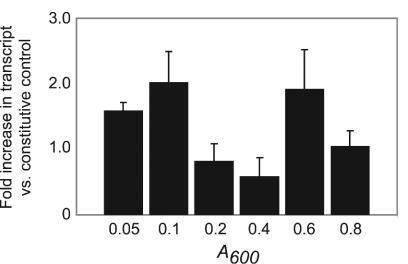

Previous studies have indicated that the expression of GAS genes can vary throughout growth (5, 24, 28, 31). TaqMan assays were performed to study the expression of srv in vitro in MGAS5005 to determine if srv responds to distinct growth phases and to provide insight into points during the bacterial growth cycle when Srv might exert the most influence on the genes it regulates. Bacteria were harvested at six points (when A600 = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8) throughout the growth cycle, total RNA was isolated, and TaqMan assays were performed as previously described (5, 31) (Fig. 2). srv was expressed at all points examined, with the maximal level of gene transcript detected at two distinct points, in early growth (A600 = 0.1) and in late exponential phase (A600 = 0.6) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

TaqMan analysis of srv gene transcription. Total RNA was isolated at six points (when A600 = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8) throughout the growth cycle. The transcription level is expressed as the fold increase in srv transcript compared to the transcript level of a constitutive control gene (gyrA). The data represent values obtained with two independently isolated RNA samples analyzed in triplicate.

As an important step toward determining the function of Srv, the srv gene was replaced in a serotype M1 strain (MGAS5005) with a spectinomycin resistance cassette according to previously described methods (21, 27, 29). The cassette consists of stop codons in all three reading frames, a 5′ consensus ribosome-binding site (GGAGG) followed by a copy of the aad9 gene, another consensus ribosome-binding site (GGAGG), and an ATG start codon (21). Previous studies have shown that in-frame insertion of this cassette does not result in downstream polar effects (21, 29). Sequencing analysis indicated recombination had occurred in frame, replacing an internal 662-bp fragment of the 720-bp srv with the 1,073-bp cassette. Southern hybridization with a probe generated from a 233-bp internal fragment of srv confirmed the absence of srv (data not shown). In addition, an srv transcript was not detected in TaqMan assays of total RNA isolated from the mutant strain (data not shown). The in vitro growth curves, the growth yields, and the average chain lengths (wild type, 7.51 cells; srv mutant, 7.37 cells) of the strains were very similar.

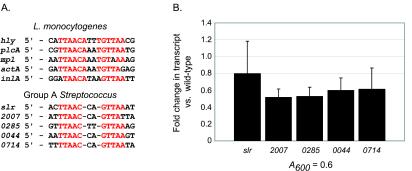

DNase I footprinting analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays have revealed that the HTH domain of PrfA binds to DNA sequences in the upstream region of genes under PrfA control (2, 8, 33). Given the similarity between the HTH domains of PrfA and Srv, we searched the M1 GAS genome sequence for the presence of the PrfA DNA binding site (TTAACANNTGTTAA) and close derivatives by using the Lasergene GeneQuest (DNAStar, Madison, Wis.) software application. We identified a 12-bp symmetric sequence located between −28 and −207 bp upstream of the start codon of five GAS genes (see below). This sequence (TTAACNNGTTAA) matched 10 of 14 bases present in the PrfA binding site (Fig. 3A.). It is important to note that nucleotide variation among PrfA binding sites has been observed (e.g., hly versus mpl) (10), so we allowed for subtle variation in our consideration of possible sequences. The identified genes are located throughout the GAS genome, and BLAST analysis of the inferred amino acid sequences assigned the following putative functions: Slr, homolog of L. monocytogenes internalin A plus B (consensus sequence located at position −29) (29); SPy2007, homolog of Lmo0153, an L. monocytogenes high-affinity zinc binding lipoprotein (−43); SPy0285, ATP binding protein (−207); SPy0044, zinc-containing dehydrogenase (−113); and SPy 0714, zinc binding protein AdcA (−28).

FIG. 3.

Identification of a possible Srv DNA binding site in GAS. (A) The publicly available GAS serotype M1 genome sequence was analyzed for the presence of a sequence similar to the PrfA DNA binding site (TTAACANNTGTTAA) (PrfA box). A sequence matching 10 of 14 bases in the PrfA box was identified in the region immediately upstream of five GAS genes. A multiple sequence alignment of the PrfA box of five L. monocytogenes genes and the possible Srv DNA binding site is shown with conserved residues highlighted in red. (B) TaqMan assays were used to detect the level of gene transcript present in vitro in the mutant and wild-type strains. The fold change in transcript level compared to the level of the wild-type strain is shown for RNA isolated at an A600 of 0.6, a point at which srv expression is elevated in vitro. The transcript levels were measurably lower in the mutant strain for each gene possessing the possible Srv promoter sequence. slr has recently been described (21, 29). 2007, spy2007; 0285, spy0285; 0044, spy0044; 0714, spy0714.

To test the hypothesis that Srv actively influences the transcription of these genes, TaqMan assays were used to detect the level of gene transcript present in vitro in the mutant and wild-type strains (Fig. 3B.). Transcript levels were compared at an A600 of 0.6, a point at which srv expression is elevated in vitro (Fig. 2). Transcript levels were measurably lower for each gene in the mutant strain compared to wild-type expression levels; however, the overall effect was not very dramatic. One must take into account that the present studies were conducted in vitro under conditions optimal for GAS growth. There is ample evidence that many bacterial regulators respond to a specific set of environmental cues. In the case of Crp, glucose limitation leads to an increase in the intracellular level of cAMP. Binding of cAMP to the Crp N-terminal β-roll structures brings about a conformational change which permits specific binding of the HTH motif to a symmetric consensus DNA sequence located upstream of Crp-regulated genes (for a review, see reference 3). The presence of an activating cofactor has also been hypothesized for PrfA (10, 13). Growth in cellobiose inhibits the expression of PrfA-dependent genes despite the active production of PrfA, leading to the suggestion that PrfA is posttranscriptionally modified (32). As mentioned earlier, two N-terminal amino acids critical for PrfA function are conserved in the β-roll structures of Srv, prompting us to hypothesize that a cofactor may be able to interact with Srv and enhance its function. Thus, in an environment promoting Srv function, the observed differences between the transcript levels of the slr, spy2007, spy0285, spy0044, and spy0714 genes may be more pronounced.

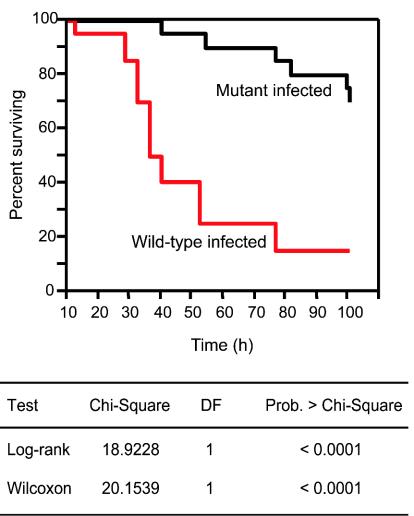

To investigate if the absence of Srv has an effect on GAS virulence, we compared the ability of the wild-type and mutant strains to cause mouse mortality following intraperitoneal inoculation. Mice received an inoculum of ∼5 × 107 CFU of GAS, an amount previously shown to result in the death of >80% of the animals tested (22). Compared to mortality in mice injected with the wild-type strain, the rate of mortality was significantly reduced in mice injected with the mutant strain (log-rank test, P < 0.0001; Wilcoxon test, P < 0.0001), with 15 of 20 mice surviving for greater than 100 h (Fig. 4). Only three mice injected with the wild-type strain survived beyond 100 h (Fig. 4), with a mean survival time of 47.2 ± 4.45 h. Thus, Srv is required for full GAS virulence under the conditions tested.

FIG. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the relative rate of mouse mortality caused by wild-type and isogenic mutant strains lacking srv. Two groups of 20 female CD-1 Swiss mice were challenged intraperitoneally with ∼5.0 × 107 CFU (0.2 ml) of the wild-type or srv mutant strain. The difference in the rate of mouse mortality was significant based on two statistical tests (log-rank and Wilcoxon tests). DF, degree of freedom; Prob., probability.

In summary, we report the first GAS member of the Crp/Fnr family of regulators, srv. The majority of well-studied proteins belonging to the Crp/Fnr family reside in gram-negative bacteria. A BLASTP analysis of Srv identified uncharacterized homologs in Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, and other organisms, but only Fnr of Bacillus subtilis, Flp of Lactobacillus casei, and PrfA of L. monocytogenes are well-documented examples in gram-positive organisms (6, 14, 19). Thus, studies defining the environmental cues promoting Srv activity and research into the functional nature of the Srv N- and C-terminal domains will undoubtedly provide insight into a growing new class of gram-positive regulators.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisno, A. L., M. O. Brito, and C. M. Collins. 2003. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bockmann, R., C. Dickneite, B. Middendorf, W. Goebel, and Z. Sokolovic. 1996. Specific binding of the Listeria monocytogenes transcriptional regulator PrfA to target sequences requires additional factor(s) and is influenced by iron. Mol. Microbiol. 22:643-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busby, S., and R. H. Ebright. 1999. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J. Mol. Biol. 293:199-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty, T., M. Leimeister-Wachter, E. Domann, M. Hartl, W. Goebel, T. Nichterlein, and S. Notermans. 1992. Coordinate regulation of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes requires the product of the prfA gene. J. Bacteriol. 174:568-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaussee, M. S., R. O. Watson, J. C. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz Ramos, H., L. Boursier, I. Moszer, F. Kunst, A. Danchin, and P. Glaser. 1995. Anaerobic transcription activation in Bacillus subtilis: identification of distinct FNR-dependent and -independent regulatory mechanisms. EMBO J. 14:5984-5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickneite, C., R. Bockmann, A. Spory, W. Goebel, and Z. Sokolovic. 1998. Differential interaction of the transcription factor PrfA and the PrfA-activating factor (Paf) of Listeria monocytogenes with target sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 27:915-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmer, M., B. deCrombrugghe, I. Pastan, and R. Perlman. 1970. Cyclic AMP receptor protein of E. coli: its role in the synthesis of inducible enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 66:480-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goebel, W., J. Kreft, and R. Böckmann. 2000. Regulation of virulence genes in pathogenic Listeria spp., p. 499-506. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Graham, M. R., L. M. Smoot, C. A. Migliaccio, K. Virtaneva, D. E. Sturdevant, S. F. Porcella, M. J. Federle, G. J. Adams, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Virulence control in group A Streptococcus by a two-component gene regulatory system: global expression profiling and in vivo infection modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13855-13860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green, J., C. Scott, and J. R. Guest. 2001. Functional versatility in the CRP-FNR superfamily of transcription factors: FNR and FLP. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 44:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herler, M., A. Bubert, M. Goetz, Y. Vega, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, and W. Goebel. 2001. Positive selection of mutations leading to loss or reduction of transcriptional activity of PrfA, the central regulator of Listeria monocytogenes virulence. J. Bacteriol. 183:5562-5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irvine, A. S., and J. R. Guest. 1993. Lactobacillus casei contains a member of the CRP-FNR family. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji, Y., N. Schnitzler, E. DeMaster, and P. Cleary. 1998. Impact of M49, Mrp, Enn, and C5a peptidase proteins on colonization of the mouse oral mucosa by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 66:5399-5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolb, A., S. Busby, H. Buc, S. Garges, and S. Adhya. 1993. Transcriptional regulation by cAMP and its receptor protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:749-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lampidis, R., R. Gross, Z. Sokolovic, W. Goebel, and J. Kreft. 1994. The virulence regulator protein of Listeria ivanovii is highly homologous to PrfA from Listeria monocytogenes and both belong to the Crp-Fnr family of transcription regulators. Mol. Microbiol. 13:141-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaPenta, D., C. Rubens, E. Chi, and P. P. Cleary. 1994. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12115-12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leimeister-Wachter, M., C. Haffner, E. Domann, W. Goebel, and T. Chakraborty. 1990. Identification of a gene that positively regulates expression of listeriolysin, the major virulence factor of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8336-8340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lingnau, A., E. Domann, M. Hudel, M. Bock, T. Nichterlein, J. Wehland, and T. Chakraborty. 1995. Expression of the Listeria monocytogenes EGD inlA and inlB genes, whose products mediate bacterial entry into tissue culture cell lines, by PrfA-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 63:3896-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukomski, S., N. P. Hoe, I. Abdi, J. Rurangirwa, P. Kordari, M. Liu, S. J. Dou, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Nonpolar inactivation of the hypervariable streptococcal inhibitor of complement gene (sic) in serotype M1 Streptococcus pyogenes significantly decreases mouse mucosal colonization. Infect. Immun. 68:535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukomski, S., K. Nakashima, I. Abdi, V. J. Cipriano, R. M. Ireland, S. D. Reid, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and characterization of the scl gene encoding a group A Streptococcus extracellular protein virulence factor with similarity to human collagen. Infect. Immun. 68:6542-6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIver, K. S., and R. L. Myles. 2002. Two DNA-binding domains of Mga are required for virulence gene activation in the group A Streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1591-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIver, K. S., and J. R. Scott. 1997. Role of mga in growth phase regulation of virulence genes of the group A Streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 179:5178-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milohanic, E., P. Glaser, J. Y. Coppee, L. Frangeul, Y. Vega, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, F. Kunst, P. Cossart, and C. Buchrieser. 2003. Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes identifies three groups of genes differently regulated by PrfA. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1613-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musser, J. M., and R. M. Krause. 1998. The revival of group A streptococcal diseases, with a commentary on staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, p. 185-218. In R. M. Krause, J. Gallin, and A. Gauci (ed.), Emerging infections. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 27.Podbielski, A., B. Spellerberg, M. Woischnik, B. Pohl, and R. Lutticken. 1996. Novel series of plasmid vectors for gene inactivation and expression analysis in group A streptococci (GAS). Gene 177:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. A. Leonard, and K. H. Schmidt. 1999. Characterization of nra, a global negative regulator gene in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1051-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid, S., A. G. Montgomery, J. M. Voyich, F. R. DeLeo, B. Lei, R. M. Ireland, N. M. Green, M. Liu, S. Lukomski, and J. Musser. 2003. Characterization of an extracellular virulence factor made by group A Streptococcus with homology to the Listeria monocytogenes internalin family of proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:7043-7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, J. K. Buss, B. Lei, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Multilocus analysis of extracellular putative virulence proteins made by group A Streptococcus: population genetics, human serologic response, and gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7552-7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, G. L. Sylva, J. M. Voyich, E. T. Stenseth, F. R. DeLeo, T. Palzkill, D. E. Low, H. R. Hill, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Postgenomic analysis of four novel antigens of group A Streptococcus: growth phase-dependent gene transcription and human serologic response. J. Bacteriol. 184:6316-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renzoni, A., A. Klarsfeld, S. Dramsi, and P. Cossart. 1997. Evidence that PrfA, the pleiotropic activator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes, can be present but inactive. Infect. Immun. 65:1515-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheehan, B., A. Klarsfeld, R. Ebright, and P. Cossart. 1996. A single substitution in the putative helix-turn-helix motif of the pleiotropic activator PrfA attenuates Listeria monocytogenes virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 20:785-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheehan, B., A. Klarsfeld, T. Msadek, and P. Cossart. 1995. Differential activation of virulence gene expression by PrfA, the Listeria monocytogenes virulence regulator. J. Bacteriol. 177:6469-6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shetron-Rama, L. M., K. Mueller, J. M. Bravo, H. G. Bouwer, S. S. Way, and N. E. Freitag. 2003. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes mutants with high-level in vitro expression of host cytosol-induced gene products. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1537-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zubay, G., D. Schwartz, and J. Beckwith. 1970. Mechanism of activation of catabolite-sensitive genes: a positive control system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 66:104-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]