Abstract

Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination is efficacious for newborns or adults with no previous exposure to environmental mycobacteria. To determine the relative contribution and the nature of γδ T-cell receptor-positive T cells in newborns, compared to CD4+ T cells, in immunity induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination, 4-week-old specific-pathogen-free pigs were vaccinated with M. bovis BCG and monitored by following the γδ T-cell immune responses. A flow cytometry-based proliferation assay and intracellular staining for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) were used to examine γδ T-cell responses. Pigs were found to mount Th1-like responses to M. bovis BCG vaccination as determined by immunoproliferation and IFN-γ production. The γδ T-cell lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production to stimulation with mycobacterial antigens were significantly enhanced by M. bovis BCG vaccination. The relative number of proliferating γδ T cells after stimulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv culture filtrate protein was higher than that of CD4+ T cells at an early time point after M. bovis BCG vaccination, but CD4+ T cells were found to be more abundant at a later time point. Although the γδ T-cell responses were dependent on the presence of CD4+ T cells for the cytokine interleukin-2, the enhanced γδ T cells were due to the intrinsic changes of γδ T cells caused by M. bovis BCG vaccination rather than being due solely to help from CD4+ T cells. Our study shows that γδ T cells from pigs at early ages are functionally enhanced by M. bovis BCG vaccination and suggests an important role for this T-cell subset in acquired immunity conferred by M. bovis BCG vaccination.

Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causal agent of tuberculosis, is the leading cause of death from a single infectious organism in humans (29). Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is the only vaccine available that protects humans from tuberculosis. However, the use of this vaccine has been questioned due to its huge variation in efficacy between trials (12). Despite the controversial efficacy of M. bovis BCG, accumulating meta-analyses suggested that M. bovis BCG could reduce the risk of tuberculosis by 50% (6). Furthermore, neonatal M. bovis BCG vaccination consistently imparts protection against the childhood manifestations of the disease in many populations (9). The observed protective efficacy of M. bovis BCG can be attributed to its preference for cell-mediated responses (8, 21, 26, 30), which are believed to be the most crucial protective response against M. tuberculosis infection.

Although CD4+ αβ T cells are the most critical population of immune cells to confer protection against tuberculosis (23, 25), there is increasing evidence that γδ T cells contribute to immunity against tuberculosis and that they possess unique immunological functions (4). γδ T cells recognize a wide range of antigens, including small organic phosphate molecules (34, 35) and unprocessed protein antigens (31). According to studies with mice, γδ T cells appear to play an important role in early protection (10, 19, 22). Although the protective role of γδ T cells in humans have not been proven, their contribution to protection against tuberculosis has been strongly suggested by the high frequency of mycobacterial antigen-specific γδ T cells, especially Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, the major γδ T-cell subpopulation in human blood (15, 20), and their ability to produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and cytotoxicity (11, 36).

As mentioned above, consistently positive results have been obtained for M. bovis BCG vaccination in newborn infants; thus, their profiles of immune response to neonatal M. bovis BCG vaccination would more likely represent the most relevant information. However, studies on immune response to M. bovis BCG vaccination in humans has been performed predominantly in adult subjects. In adults aged 18 to 45 years, γδ T cells, specifically Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells, were found to be the most prominent T-cell subtype induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination (16).

It is important to take into account the fact that the mycobacterium-specific human Vγ9Vδ2+ T-cell subtype accounts for a small portion of blood γδ T cells at birth, and then extrathymically expand with unknown antigenic stimulation, to become the major γδ T-cell subtype (27). For this reason, a large fraction of human γδ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from purified protein derivative-negative, non-M. bovis BCG-vaccinated individuals proliferate in response to killed M. tuberculosis (20). According to studies upon intestinal γδ T cells, the antigen specificity of γδ T cells in the early period after birth is still polyclonal and becomes restricted with age (18). It is tempting to speculate that this difference in the property of γδ T cells between newborns and adults could affect the outcome of M. bovis BCG vaccination.

Since it is difficult to use human subjects to investigate neonatal M. bovis BCG vaccination, the development of relevant animal models is required to allow extensive sampling and a long period of follow-up after M. bovis BCG vaccination. To meet this demand, we adopted swine as an animal model for studying the function of γδ T cells. Swine are a potential candidate for studying tuberculosis because pigs are natural hosts to Mycobacterium species and they develop lesions similar to those of humans after M. bovis infection (3). Furthermore, the generation of swine γδ T-cell receptor repertoires over developmental stages is similar to that of humans (17).

In an attempt to investigate immune responses to human neonatal vaccination, specific-pathogen-free, 4-week-old pigs were chosen for this study. With these animals, the proliferative response of γδ T cells to mycobacterial antigens were monitored over a period of 13 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination and compared with that of CD4+ T cells. In addition, IFN-γ production and the memory-like response of γδ T cells were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Specific-pathogen-free, mixed-breed male pigs at 3 to 5 week of age were obtained from Nextran (Rochester, Minn.). All animals were screened by lymphocyte proliferation and for IFN-γ production against mycobacterial antigens to confirm nonexposure to mycobacteria. All pigs were randomly assigned to M. bovis BCG vaccination (n = 4) or control (n = 4) groups and housed in the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care. Research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota. Animals for M. bovis BCG vaccination were inoculated with 1 × 107 CFU of Copenhagen M. bovis BCG (Copenhagen 1331, Stalines Seruminstad Copenhagen) subcutaneously in the right inguinal area in 1 ml of saline. The placebo group received 1 ml of saline only. Each group was housed in a separate isolation room throughout the study.

Reagents for in vitro stimulation of PBMCs.

Mycobacterial antigens, culture filtrate protein, culture filtrate protein depleted of lipoarabinomannan (culture filtrate protein-L), and heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells were provided by J. Belisle (Colorado State University), and concanavalin A was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Recombinant human IL-2 obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.) was verified to be cross-reactive with swine lymphocytes.

Isolation of PBMCs and lymphoproliferation assay.

PBMCs were separated from whole blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient. Cells were treated with red blood cell lysing buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA; pH 7.4) to lyse red blood cells. PBMCs freshly harvested from M. bovis BCG and placebo recipients were incubated in 96-well tissue culture plates (4 × 105 cells in 0.2 ml/well) in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 units of penicillin G per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin B per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine. Cells were cultured with medium alone, concanavalin A (1 μg/ml), or optimal concentrations of culture filtrate protein (2 μg/ml), culture filtrate protein-L (2 μg/ml), and heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells (2 μg/ml) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cultures were incubated for 2 days, pulsed with 1 μCi of tritiated thymidine (Amersham International, Amersham, United Kingdom), and further incubated for 18 h before measuring the cell-associated radioactivity. Results were expressed as mean total counts per minute of mean net counts per minute (net counts per minute = antigen counts per minute − control phosphate-buffered saline counts per minute).

CD4 and γδ T-cell depletion.

For CD4+ T-cell depletion, PBMCs were stained with mouse unlabeled monoclonal anti-swine CD4 antibody (monoclonal antibody 74-12-4; Veterinary Medical Research and Development, Pullman, Wash.) at 5 μg for 1 × 107 PBMCs. The PBMCs were washed, and magnetic goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.) were added (20 μl of goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin microbeads for 107 total PBMCs). CD4+ T cells were separated in MiniMACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec). CD4-depleted cells had less than 0.04% residual CD4+ cells.

For γδ T-cell depletion, PBMCs were depleted of γδ T cells with an unlabeled anti-swine γδ T-cell receptor monoclonal antibody (PGBL22A; Veterinary Medical Research and Development) at 5 μg for 1 × 107 PBMC and magnetic goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin microbeads. In all γδ depletion experiments, less than 0.05% of the residual cells were γδ T-cell receptor-positive T cells.

PBMC staining with PKH26 red fluorescent cell linker.

PBMCs or CD4-depleted PBMCs were stained with PKH26 fluorescent dye according to the manufacturer's protocol (Sigma). Cells (1 × 107) were washed with fetal bovine serum-free RPMI and resuspended in 500 μl of diluent C (Sigma). They were then mixed with 500 μl of 10−6 M PKH26 dye (Sigma), incubated for 3.5 min at room temperature and for 1 min after adding 1 ml of fetal bovine serum, and washed with medium. The PKH26-stained cells were then added to a 96-well plate at 4 × 105 cells/well and incubated with medium alone or mycobacterial antigens at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified chamber. After 6 days of culture, the cells were stained for cell surface markers (CD4 and γδ T-cell receptor) and analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.).

CD4-depleted cell populations stained with PKH26 dye were stimulated with mycobacterial antigens in the presence or absence of recombinant human IL-2 (1 ng/ml). Only viable cells as determined by forward and side scatter (as previously determined) were included in the analyses. Proliferation profiles were determined as the number of cells proliferating in antigen-stimulated wells minus the number of cells proliferating in nonstimulated wells. Data are presented as the mean number of cells that had proliferated per 10,000 PBMCs ± standard error of the mean.

IFN-γ detection by ELISA.

PBMCs or PBMCs depleted of CD4 T cells or γδ T cells were incubated in 96-well plates (4 × 105 cells in 200 μl/well) with medium alone, with optimal concentrations of culture filtrate protein (2 μg/ml) for 4 days, or concanavalin A (1 μg/ml) for 2 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cell-free supernatants were collected and frozen at −70°C until cytokine levels were determined by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ELISA plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with mouse anti-swine IFN-γ monoclonal antibody A151D5B8 (2.5 μg/ml) (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.) in 0.1 M sodium carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 37°C for 1 h and at 4°C overnight. Plates were blocked with blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin) after washing with phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (0.1%).

Samples (50 μl) and biotin-labeled anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (50 μl; final concentration, 0.25 μg/ml) (A151D13C5, Biosource International) were added to wells and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After being washed, peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (R & D Systems) was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h. After a thorough washing, tetramethylbenzidine substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for approximately 20 min. Optical density at 450 nm was determined with an automated ELISA reader. Swine recombinant IFN-γ (Biosource International) was used as a standard to determine cytokine concentrations.

Intracellular cytokine detection for swine IFN-γ.

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). PBMCs were incubated in 24-well plates (2 × 106 cells in 1 ml/well) with medium alone or with optimal concentrations of M. tuberculosis H37Rv culture filtrate protein (2 μg/ml) for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. On the third day, monensin (GolgiStop, PharMingen) was added 6 h prior to harvesting to block intracellular transport processes, which result in the accumulation of cytokine proteins in the Golgi complex and thereby enhance cytokine-staining signals. Cells were harvested and stained with anti-swine and anti-swine γδ T-cell receptor followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Ctyoperm kit (Pharmingen), and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-swine IFN-γ (P2G10, Pharmingen) for intracellular IFN-γ. Stained cells were run on a flow cytometer and analyzed. Results are expressed as the number of cells producing IFN-γ per 10,000 PBMCs.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between means were analyzed by paired or unpaired Student t tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

M. bovis BCG vaccination induces mycobacteriun-specific T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production.

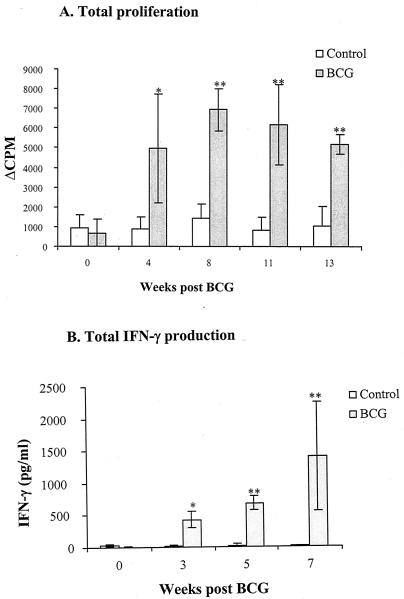

To confirm that swine are the appropriate animal model for studying cell-mediated immune responses to M. bovis BCG vaccination, lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production were measured in pigs following M. bovis BCG vaccination. To prevent complications of preexposure to environmental mycobacteria, which is common to humans and pigs in commercial farms, and to facilitate the identification of memory T-cell responses induced by M. bovis BCG, we obtained pigs raised in a specific-pathogen-free environment. PBMCs were obtained from animals at various times after vaccination (0 to 13 weeks), and proliferative responses and IFN-γ production induced by culture filtrate protein were measured with a [3H]thymidine uptake assay (Fig. 1A) and IFN-γ sandwich ELISA (Fig. 1B), respectively.

FIG. 1.

Cell-mediated immune responses to culture filtrate protein in swine after vaccination with M. bovis BCG. PBMCs were stimulated in vitro with culture filtrate protein and proliferative response (A) and IFN-γ production (B) were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation and IFN-γ sandwich ELISA, respectively. Results are shown as the geometric mean values (± standard error of the mean) obtained from four controls and three M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals. Proliferative responses are expressed as the change in mean cpm of triplicate analyses. The proliferative response of unstimulated cultures was in the range of 40 to 200 cpm. IFN-γ release into culture supernatants is shown. IFN-γ was not detected in unstimulated cultures. Statistically significant increase in cellular responses to M. bovis BCG vaccination are labeled: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, according to Student's t test.

M. bovis BCG vaccination induced significant increases in lymphoproliferation and in IFN-γ production to in vitro culture filtrate protein stimulation compared to controls (P < 0.01). No significant differences between M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs and the controls were observed in terms of prevaccination immunoreactivity to culture filtrate protein stimulation (P > 0.1). T-cell proliferative responses were significant by 4 weeks and maintained for 13 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination. Similarly, the IFN-γ production of M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs was significant by 3 weeks and was sustained for at least 7 weeks. The mean proliferative responses stimulated by concanavalin A were not significantly different between the two groups throughout this study (data not shown), indicating that M. bovis BCG vaccination did not cause an increase in nonspecific T-cell reactivity. Lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production in cultures incubated with medium alone were not increased in the M. bovis BCG group postvaccination (data not shown).

M. bovis BCG vaccination induces enhanced responsiveness in γδ T cells to secondary in vitro stimulation with mycobacterial antigens.

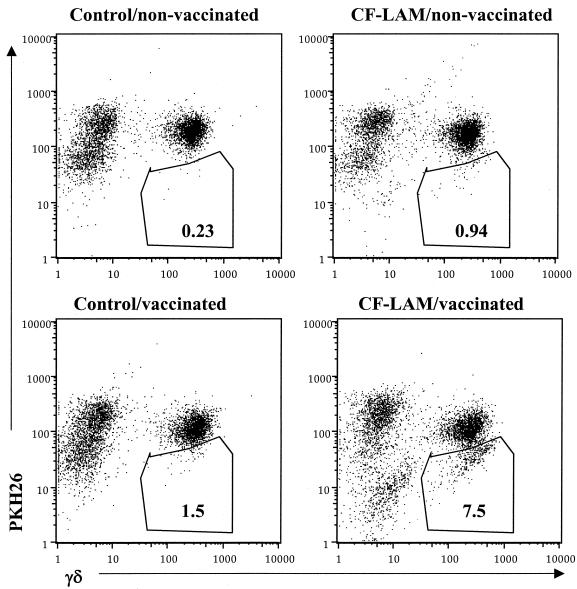

To identify the specific subsets of T cells induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination, flow cytometry with PKH26 fluorescent dyes (1, 37) was used. PKH26 staining intensity diminishes with each cell division, resulting in a decreased mean fluorescence intensity, which enables the detection of proliferating cells. This method was selected instead of counting the absolute number of T-cell subsets after antigen stimulation because the mycobacterial antigens used in this study increased γδ T-cell viability, resulting in a significant increase in viable cell numbers in culture filtrate protein-stimulated cultures versus nonstimulated cultures.

Representative two-parameter dot plots obtained by flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs from one M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pig and one control pig are shown in Fig. 2 for γδ T-cell proliferation 5 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination. PBMCs were stained with PKH-26 red dye, stimulated with culture filtrate protein-L or medium control for 6 days, and stained with reagents specific for γδ T-cell receptor. Analysis of the PBMCs from a representative M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animal demonstrated that 1.5% of the nonstimulated γδ T cells were PHK26 low (proliferating), whereas 7.5% of the culture filtrate protein-L-stimulated γδ T cells were low. Stimulation of PBMCs from a representative control animal with culture filtrate protein-L did not result in a diminishment of PKH26 intensity (0.23% of nonstimulated γδ T cells were low) compared to nonstimulated cells (e.g., 0.94% of stimulated γδ T cells were low) from the same animal. The percentage of proliferating cells correlated with the results from [3H]thymidine uptake assay and the PKH26 low population constituted the lymphoblasts in forward and side light scatter, verifying that PKH26 low cells were the proliferating cell population (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

In vitro stimulation of PBMC with culture filtrate protein-L results in γδ T-cell proliferation. Shown are two-parameter dot plots of flow analyses indicating the number of γδ T cells present in cultures of PBMCs from one representative M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pig and one control pig after in vitro stimulation with culture filtrate protein-L or culture medium for 6 days. The y axis represents PKH-26 red dye, and the x axis represents the fluorescein isothiocyanate fluorescence of γδ T cells. The percentage of proliferating cells is shown in gated areas (PKH26 low). These results were obtained from PBMCs isolated from animals 5 weeks post-M. bovis BCG vaccination.

To determine proliferation values from PKH26 staining, background proliferation (proliferation in nonstimulated cultures) was subtracted from the proliferation in culture filtrate protein-stimulated cultures of CD4+ T cells and γδ T cells. The results for T-cell expansion studies with PBMCs from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs and controls at 5, 11, and 13 weeks following M. bovis BCG vaccination are presented in Table 1. The proliferative responses of both γδ T cells and CD4+ T cells in culture filtrate protein-stimulated PBMC from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs were not significantly (P = 0.065 and P = 0.071, respectively) greater than from control pigs at 5 weeks, but were significantly higher at 11 and 13 weeks (P < 0.01). Thus, the proliferative response of γδ T cells as well as CD4+ T cells to culture filtrate protein was induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination. In M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs, γδ T cells were significantly higher in the proliferative response to culture filtrate protein than CD4+ T cells at 5 weeks (P < 0.05), but CD4+ T-cell proliferative response became significantly higher than γδ T cells at 11 (P < 0.05) and 13 weeks (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Proliferation of CD4+ T cells and γδT cells in PBMCs stimulated with culture filtrate proteina

| Time post- vaccination (wk) | Group (no.) | Mean no. of T cells ± SEM

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | γδ | ||

| 5 | Control pigs (4) | 20.5 ± 37.1 | 71.8 ± 48.3 |

| BCG-vaccinated pigs (3) | 193.3 ± 149.7 | 297.3 ± 186.4c | |

| 11 | Control pigs (4) | 75.5 ± 92.7 | 91.75 ± 48.9 |

| BCG-vaccinated pigs (3) | 1530.0 ± 406.3b | 652.6 ± 220.7b,c | |

| 13 | Control pigs (4) | 39 ± 78 | 142.5 ± 59 |

| BCG-vaccinated pigs (3) | 1053.3 ± 202.6b | 556.6 ± 168.6b,c | |

Data represent the mean number of cells that had proliferated per 10,000 PBMCs in response to stimulation with culture filtrate protein as determined by flow cytometry and PKH-26 staining. Treatment groups included control pigs and BCG-vaccinated pigs.

P < 0.05 comparing the number of cells in BCG and control groups by unpaired Student t test.

P < 0.05 comparing the number of γδ T cells and CD4 T cells from BCG-vaccinated pigs by paired Student t test.

To investigate whether differences in response of each T-cell subset existed in the recognition of various classes of mycobacterial antigens after M. bovis BCG vaccination, PBMCs were stimulated with either culture filtrate protein, culture filtrate protein-L, or heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells 5 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination (Table 2). Overall, T-cell proliferation was the highest in those stimulated with heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells, followed by culture filtrate protein-L and culture filtrate protein. The heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole-cell antigens appeared to preferentially stimulate CD4+ T cells, while the culture filtrate protein antigen preferentially stimulated γδ T cells. Stimulation with culture filtrate protein-L caused the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and of γδ T cells equally. The proliferative responses of γδ T cells and CD4+ T cells in PBMCs stimulated with culture filtrate protein-L were significantly (P < 0.02) higher in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs than controls. Because stimulation with heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells caused substantial γδ T-cell proliferation in the controls, differences in γδ T-cell proliferation between the M. bovis BCG-vaccinated group and controls were not significant (P = 0.226). However, CD4+ T-cell response in heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole-cell-stimulated PBMCs was significantly higher in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs than the controls (P = 0.039).

TABLE 2.

Proliferation of lymphocyte subsets in response to stimulation with M. tuberculosis antigensa

| T cells | Group | Mean no. of proliferating cells/10,000 PBMCs ± SEM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP | CFP-L | WC | ||

| CD4 | Control pigs | 20.5 ± 37.1 | 45.8 ± 95.4 | 275.8 ± 250.8 |

| BCG-vaccinated pigs | 193.3 ± 149.7 | 484.3 ± 200.7b | 881.3 ± 331.9b | |

| γδ | Control pigs | 71.8 ± 48.3 | 94.8 ± 22.6 | 326.8 ± 103.3 |

| BCG-vaccinated pigs | 297.3 ± 186.4c | 400.6 ± 155.6b | 548 ± 307.1c | |

PBMCs from BCG-vaccinated animals (n = 3) and controls (n = 4) were stained with PKH-26 and stimulated with 2 μg of culture filtrate protein (CFP), CFP-L, or Treat-killed M. tuberculosis (WC) for 6 days.

P < 0.05 comparing the number of cells in BCG and control groups by unpaired Student t test.

P < 0.05 comparing the number of γδ T cells and CD4 T from BCG-vaccinated pigs by paired Student t test.

M. bovis BCG vaccination primes γδ T cells.

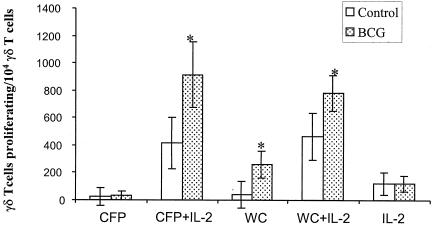

γδ T cells from nonsensitized humans have been shown to be readily induced by killed M. tuberculosis in the presence of IL-2 (20). We investigated whether γδ T-cell responsiveness was due to direct priming of γδ T cells by M. bovis BCG vaccination or to a simple manifestation of helper function by M. bovis BCG-activated IL-2-secreting CD4+ T cells. PBMCs from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals and controls were depleted of CD4+ T cells, and CD4-depleted PBMCs were stained with PKH-26 to visualize the γδ T-cell proliferation (Fig. 3). CD4 depletion abolished γδ T-cell proliferation to culture filtrate protein, while γδ T cells proliferated in the presence of CD4 T cells (in total PBMCs) or recombinant human IL-2. This result indicates that IL-2 is an important mediator secreted by helper CD4+ T cells to costimulate γδ T cells.

FIG. 3.

Direct priming of γδ T cells by M. bovis BCG vaccination. γδ T-cell proliferation in CD4-depleted PBMCs was compared in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals and controls at 11 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination. PBMCs were stained with PKH-26 and then stimulated with culture filtrate protein (CFP) or heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells (WC) in the presence or absence of recombinant human IL-2 (1 ng/ml). The significant increase in γδ T-cell proliferation among the CD4-depleted PBMCs of M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs (n = 3) compared to that of controls (n = 4) is indicated (*, P < 0.05).

When CD4-depleted PBMCs were treated with culture filtrate protein and recombinant human IL-2, γδ T cells from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs showed greater expansion compared with those from nonvaccinated controls (P = 0.025), suggesting that γδ T cells are intrinsically enhanced by M. bovis BCG vaccination. Substantial numbers of γδ T cells from control pigs proliferated upon stimulation with culture filtrate protein and heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells in combination with recombinant IL-2, which is consistent with the results of Kabelitz et al. (20). Unlike stimulation with culture filtrate protein, stimulation with heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells, even in the absence of recombinant human IL-2, caused increased γδ T-cell expansion in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals (P = 0.033), suggesting that heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells components use unknown pathways independent of CD4+ T cells, by which they elicit γδ T-cell proliferation.

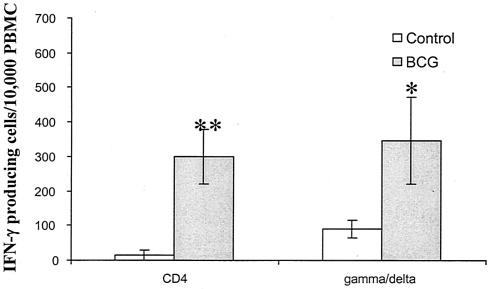

M. bovis BCG vaccination-induced IFN-γ production by γδ T cells.

To investigate whether M. bovis BCG vaccination enhances IFN-γ production by γδ T cells, we measured antigen-specific IFN-γ production by γδ T cells and compared this with that of CD4+ T cells. PBMCs were stimulated with culture filtrate protein and analyzed for the number of CD4+ and γδ T cells producing IFN-γ by intracellular staining. The numbers of IFN-γ producing γδ T cells were significantly (P < 0.01) higher in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs than in control pigs (Fig. 4). The number of IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells was comparable to that of CD4+ T cells in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs.

FIG. 4.

IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells and γδ T cells after culture filtrate protein stimulation. PBMCs were obtained from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs (n = 3) and controls (n = 4) at week 3 and stimulated with culture filtrate protein for 3 days. PBMCs were then stained for cell markers (CD4 and γδ T-cell receptor) and intracellular IFN-γ. Data are expressed as the mean number of IFN-γ-producing cells per 10,000 PBMCs ± standard error of the mean. Statistically significant increases in the number of IFN-γ producing cells induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination are labeled: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, according to Student's t test.

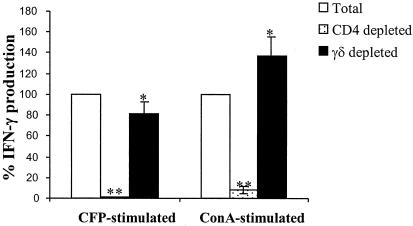

To investigate the relative contribution of γδ T cells to IFN-γ released into the cell culture supernatant from total PBMCs, PBMCs were depleted of γδ T cells or CD4+ T cells, and IFN-γ production was measured after culture filtrate protein stimulation by IFN-γ ELISA. IFN-γ release after the in vitro stimulation of PBMCs depleted of CD4+ or γδ T cells from three M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals is shown in Fig. 5. CD4 depletion blocked IFN-γ production in response to stimulation by both culture filtrate protein and concanavalin A. This result indicates that CD4+ T cells not only produce IFN-γ, but also play a critical role in helping other T-cell subsets to produce IFN-γ.

FIG. 5.

Effect of T-cell subset depletion on IFN-γ production. PBMCs and PBMCs depleted of either CD4+ T cells or γδ T cells from three M. bovis BCG-vaccinated animals at 3 weeks after M. bovis BCG vaccination were stimulated with culture filtrate protein (CFP, 2 μg/ml) for 4 days or concanavalin A (ConA, 1 μg/ml) for 2 days. Secreted IFN-γ in cultured cells was measured by sandwich ELISA. The results are standardized to the total PBMCs, assuming that IFN-γ production by total PBMCs is 100%. The asterisk indicates a value that is significantly different from total PBMCs. Significant differences are labeled: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, according to Student's t test.

Swine have a high frequency of γδ T cells in the blood, and the frequencies of γδ T cells in the blood of the three vaccinated animals were 21%, 23%, and 25%. Therefore, γδ T-cell depletion resulted in substantial αβ T-cell enrichment. αβ T cells appeared to produce IFN-γ more potently after stimulation with concanavalin A, because αβ T-cell enrichment after γδ T-cell depletion resulted in a marked increase in IFN-γ production compared to that produced by total PBMCs. In contrast, αβ T-cell enrichment exhibited lower levels of IFN-γ after stimulation with culture filtrate protein compared to total PBMCs, suggesting that γδ T cells contribute to antigen-specific IFN-γ production, which is consistent with the observation of intracellular IFN-γ staining.

DISCUSSION

It is widely believed that the most critical T-cell subtype in immunity against tuberculosis is the mycobacterium-reactive CD4+ αβ T cells, which activates macrophages to control intracellular mycobacterial growth. Although the protective role of γδ T cells has not been directly demonstrated, accumulating evidence indicates the importance of this T-cell subset in early protection (10, 19, 22) and IFN-γ production (36). The detailed role of γδ T cells in immunity induced by M. bovis BCG, specifically when the M. bovis BCG vaccination is protective, has yet to be determined. It has been shown that γδ T cells are the most prominent T-cell subtype reactive with mycobacterial antigens in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated adult humans (ranging from 18 to 45 years) (16).

To identify the relative contribution of γδ T cells to in vitro response to mycobacterial antigens following M. bovis BCG vaccination, we used 4-week-old pigs, because neonatal M. bovis BCG vaccination consistently imparts protection against the childhood manifestations of disease in many populations (9), while adult pulmonary manifestations are not prevented by M. bovis BCG vaccination (33). Differences between newborns and adult humans also exist in the aspect of γδ T cells. In newborns, Vγ9+ Vδ2+ cells represent a fraction of circulating γδ T cells but constitute a major γδ T-cell population in adults (27). Furthermore, the T-cell receptor δ repertoire in the human intestine is polyclonal at birth and becomes restricted over age (18).

The pigs in this study were raised in specific-pathogen-free conditions to minimize possible preexposure to mycobacterial antigens. A difference was observed in terms of the T-cell subsets induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination between specific-pathogen-free pigs and pigs purchased from conventional swine farms. The conventionally grown pigs examined were found to possess various initial mycobacterial reactivities before M. bovis BCG vaccination, as has been shown in adult humans (16, 30). In conventionally grown pigs, the predominant γδ T-cell response to M. bovis BCG vaccination was found along with low CD4+ T-cell responses, which is similar to the response of adult human T-cell subsets to M. bovis BCG (16). In contrast, in the specific-pathogen-free pigs, the proliferative response of γδ T cells was higher than that of CD4+ T cells at the early time point, and then the CD4+ T cells became more dominant than γδ T cells during the later period after M. bovis BCG vaccination. Thus, the immune response to M. bovis BCG vaccination in young animals with a minimal exposure to environmental mycobacteria may be useful for elucidating γδ T-cell functions as a protective immune component induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination.

Our results show that considerable numbers of γδ T cells from naïve animals expanded to culture filtrate protein and heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells in the presence of recombinant human IL-2, which is consistent with studies on nonvaccinated, purified protein derivative-negative individuals showing that a substantial percentage of γδ T cells are reactive to killed M. tuberculosis in the presence of IL-2 (20). The cytokine IL-2 appears to be the major CD4 T-cell-derived helper factor for γδ T-cell proliferation (28). To rule out the possibility that enhancement of γδ T cells by M. bovis BCG vaccination is a simple manifestation of CD4+ T-cell help, CD4+ T-cell-depleted PBMCs were stimulated with mycobacterial antigens. γδ T cells from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs showed higher responses to stimulation with mycobacterial antigens and recombinant human IL-2 in the absence of CD4+ T cells than γδ T cells in control animals. Our data show, as has been found in adult humans (16), that enhanced γδ T cells after M. bovis BCG vaccination are due to intrinsic changes, which suggests that memory-like functions of these cells exist at an early age.

One of the unique functions of γδ T cells is their early role in protection against tuberculosis (22). Given that γδ T cells do not proliferate to culture filtrate protein antigens in the absence of CD4+ T cells (or IL-2), we questioned how γδ T cells play a role in primary mycobacterial infection before CD4+ T cells are activated. To address this question, we thought that IL-15 might be the strong candidate replacement for IL-2. Salmonella choleraesuis infection stimulates IL-15 production by macrophages, which serves as a growth factor for γδ T cells (24). The substantial proliferation of γδ T cells among PBMCs and among CD4-depleted PBMCs stimulated by heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole cells without IL-2 suggests that there might be cytokines, such as IL-15, which are stimulated by unknown heat-killed M. tuberculosis H37Rv whole-cell components and are responsible for γδ T-cell expansion in the absence of CD4+ T cells.

IFN-γ gene knockout mice and humans with a defect in the IFN-γ receptor showed that IFN-γ is the most critical mediator of the protective immune response to mycobacterial infection (7, 13, 23). CD4+ T cells are known to be major producers of IFN-γ, and CD8+ T cells are also an importance source of IFN-γ in mycobacterial infection (32). Human γδ T cells have also been reported to secrete IFN-γ in response to mycobacterial antigens and to be more efficient producers of IFN-γ than CD4+ T cells (14, 36). Our data confirm the ability of γδ T cells to produce IFN-γ in response to culture filtrate protein by flow cytometric analysis.

In this study, the production of IFN-γ by γδ T cells required sensitization by M. bovis BCG vaccination: γδ T-cell IFN-γ production occurred only in PBMCs from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated pigs. At an early time point after M. bovis BCG vaccination, the number of IFN-γ-producing γδ T cells was comparable to that of CD4+ T cells. To determine the relative contribution of γδ T cells to total secreted IFN-γ production into the medium from PBMCs stimulated with culture filtrate protein, γδ T cells or CD4+ T cells were depleted from PBMCs. CD4+ T-cell depletion completely blocked the total IFN-γ from PBMCs stimulated with culture filtrate protein or with concanavalin A, indicating that γδ T cells are dependent on CD4+ T cells for both antigen and mitogen-induced IFN-γ production. When γδ T cells were depleted, PBMCs stimulated with culture filtrate protein secreted slightly less IFN-γ. On the other hand, when γδ T-cell-depleted PBMCs were stimulated with concanavalin A, IFN-γ production was augmented.

Considering the high percentage of the γδ T cells in pig blood (≈20% for pigs in this study), γδ T-cell-depletion resulted in enrichment of αβ T cells, including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. If the relative contribution of γδ T cells to IFN-γ secretion was inferior to that of their αβ T-cell counterparts, γδ T-cell-depletion would cause an increase in IFN-γ, as seen in concanavalin A-stimulated PBMCs. In summary, our results show that mycobacterial antigen culture filtrate protein preferentially stimulates γδ T cells, which then contribute to the IFN-γ production following in vitro mycobacterial stimulation.

The need for an appropriate animal model for identifying protective immunity and constructing an effective vaccine against tuberculosis is apparent. To date, tuberculosis research depends mainly on murine or guinea pig models for handling convenience and genetic modifications. However, data obtained from murine models cannot be applied directly to humans, and other intermediate animal models are needed to confirm murine data before human trials. In the present study, we used swine as an animal model to investigate γδ T-cell immune response to M. bovis BCG vaccination. The pig is a proven animal model for studies of the human immune system (2) and has recently received attention as a possible source of organs for human transplantation.

Pigs also have potential in the study of tuberculosis. Like humans, swine are a natural host to Mycobacterium species and have also been shown to develop similar pathological lesions to those seen in humans following M. bovis infection (3). In addition, our data indicate that swine efficiently mount cell-mediated immune responses, including lymphoproliferation and IFN-γ production following M. bovis BCG vaccination, which is consistent with that observed in humans (8, 26, 30). Although the frequency of γδ T cells in swine blood is higher than in humans, their development of a T-cell receptor repertoire has been shown to be similar to that of humans (17). In the present study, we found that swine γδ T cells are also highly responsive to in vitro mycobacterial antigens as are those of humans (15, 16, 20), thus providing an additional rationale for the pig as a potential model of the function of γδ T cells in immunity against tuberculosis.

In summary, this study documents the γδ T-cell responses following M. bovis BCG vaccination in infant pigs and demonstrates that M. bovis BCG vaccination enhances γδ T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production to in vitro mycobacterial antigens, suggesting that γδ T cells substantially contribute to immunity induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination. However, the determination of γδ T cells as one of the protective components induced by M. bovis BCG vaccination has yet to be addressed. In addition, identification of a protective subpopulation of γδ T cells may benefit the development of a more efficient vaccine for protection against tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Jack Risdahl and Nextran for providing pigs. We thank Phillip Peterson for helpful advice. We thank Shelia Alexander for help with the FACS analysis, Maria Isabel Guedes for helping in animal experiments, and So Yeong Lee for help with the statistical analyses.

This research was funded by the NIH (5R01DA08496-07).

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashley, D. M., S. J. Bol, C. Waugh, and G. Kannourakis. 1993. A novel approach to the measurement of different in vitro leukaemic cell growth parameters: the use of PKH GL fluorescent probes. Leuk. Res. 17:873-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeker, M., R. Pabst, and H. J. Rothkotter. 1999. Quantification of B, T and null lymphocyte subpopulations in the blood and lymphoid organs of the pig. Immunobiology 201:74-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolin, C. A., D. L. Whipple, K. V. Khanna, J. M. Risdahl, P. K. Peterson, and T. W. Molitor. 1997. Infection of swine with Mycobacterium bovis as a model of human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1559-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boom, W. H. 1999. Gammadelta T cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 1:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt, L., J. Cunha, B Olsen, A. Chilima, P. Hirsch, R. Appelberg, and P. Andersen. 2002. Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:672-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewer, T. F. 2000. Preventing tuberculosis with bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine: a meta-analysis of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31(Suppl. 3):S64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casanova, J. L., and L. Abel. 2002. Genetic dissection of immunity to mycobacteria: the human model. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:581-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castes, M., J. Blackwell, D. Trujillo, S. Formica, M. Cabrera, G. Zorrilla, A. Rodas, P. L. Castellanos, and J. Convit. 1994. Immune response in healthy volunteers vaccinated with killed leishmanial promastigotes plus BCG. I: Skin-test reactivity, T-cell proliferation and interferon-gamma production. Vaccine 12:1041-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colditz, G. A., C. S. Berkey, F., Mosteller, T. F. Brewer, M. E. Wilson, E. Burdick, and H. V. Fineberg. 1995. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics 96:29-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieli, F., J. Ivanyi, P. Marsh, A. Williams, I. Naylor, G. Sireci, N. Caccamo, Di C. Sano, and A. Salerno. 2003. Characterization of lung gamma delta T cells following intranasal infection with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Immunol. 170:463-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dieli, F., Troye- M. Blomberg, J. Ivanyi, J. J. Fournie, M. Bonneville, M. A. Peyrat, G. Sireci, and A. Salerno. 2000. Vgamma9/Vdelta2 T lymphocytes reduce the viability of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:1512-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fine, P. E. 1995. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet 346:1339-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn, J. L., J. Chan, K. J. Triebold, D. K. Dalton, T. A. Stewart, and B. R. Bloom. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178:2249-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia, V. E., P. A. Sieling, J. Gong, P. F. Barnes, K. Uyemura, Y. Tanaka, B. R. Bloom, C. T. Morita, and R. L. Modlin. 1997. Single-cell cytokine analysis of gamma delta T-cell responses to nonpeptide mycobacterial antigens. J. Immunol. 159:1328-1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havlir, D. V., J. J. Ellner, K. A. Chervenak, and W. H. Boom. 1991. Selective expansion of human gamma delta T cells by monocytes infected with live Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Investig. 87:729-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoft, D. F., R. M. Brown, and S. T. Roodman. 1998. Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination enhances human gamma delta T-cell responsiveness to mycobacteria suggestive of a memory-like phenotype. J. Immunol. 161:1045-1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtmeier, W., J. Kaller, W. Geisel, R. Pabst, W. F. Caspary, and H. J. Rothkotter. 2002. Development and compartmentalization of the porcine T-cell receptor delta repertoire at mucosal and extraintestinal sites: the pig as a model for analyzing the effects of age and microbial factors. J. Immunol. 169:1993-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtmeier, W., T. Witthoft, A. Hennemann, H. S. Winter, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1997. The T-cell receptor-delta repertoire in human intestine undergoes characteristic changes during fetal to adult development. J. Immunol. 158:5632-5641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue, T., Y. Yoshikai, G. Matsuzaki, and K. Nomoto. 1991. Early appearing gamma/delta-bearing T cells during infection with Calmette Guerin bacillus. J. Immunol. 146:2754-2762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabelitz, D., A. Bender, S. Schondelmaier, B. Schoel, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1990. A large fraction of human peripheral blood gamma/delta + T cells is activated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis but not by its 65-kD heat shock protein. J. Exp. Med. 171:667-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemp, E. B., R. B. Belshe, and D. F. Hoft. 1996. Immune responses stimulated by percutaneous and intradermal bacille Calmette-Guerin. J. Infect. Dis. 174:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladel, C. H., C. Blum, A. Dreher, K. Reifenberg, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1995. Protective role of gamma/delta T cells and alpha/beta T cells in tuberculosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:2877-2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogues, T., M. E. Goodrich, L. Ryan, R. LaCourse, and R. J. North. 2001. The relative importance of T-cell subsets in immunity and immunopathology of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Exp. Med. 193:271-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishimura, H., K. Hiromatsu, N. Kobayashi, K. H. Grabstein, R. Paxton, K. Sugamura, J. A. Bluestone, and Y. Yoshikai. 1996. IL-15 is a novel growth factor for murine gamma delta T cells induced by Salmonella infection. J. Immunol. 156:663-669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orme, I. M., P. Andersen, and W. H. Boom. 1993. T-cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 167:1481-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pabst, H. F., J. C. Godel, D. W. Spady, J. McKechnie, and M. Grace. 1989. Prospective trial of timing of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination in Canadian Cree infants. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 140:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker, C. M., V. Groh, H. Band, S. A. Porcelli, C. Morita, M. Fabbi, D. Glass, J. L. Strominger, and M. B. Brenner. 1990. Evidence for extrathymic changes in the T-cell receptor/repertoire. J. Exp. Med. 171:1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pechhold, K., D. Wesch, S. Schondelmaier, and D. Kabelitz. 1994. Primary activation of V gamma 9-expressing gamma delta T cells by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Requirement for Th1-type CD4 T-cell help and inhibition by IL-10. J. Immunol. 152:4984-4992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raviglione, M. C., D. Snider, and A. J. Kochi. 1995. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA 273:220-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravn, P., H. Boesen, B. K. Pedersen, and P. Andersen. 1997. Human T-cell responses induced by vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Immunol. 158:1949-1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schild, H., N. Mavaddat, C. Litzenberger, E. W. Ehrich, M. M. Davis, J. A. Bluestone, L. Matis, R. K. Draper, and Y. H. Chien. 1994. The nature of major histocompatibility complex recognition by gamma delta T cells. Cell. 76:29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schluger, N. W. 2001. Recent advances in our understanding of human host responses to tuberculosis. Respir. Res. 2:157-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterne, J. A., L. C. Rodrigues, and I. N. Guedes. 1998. Does the efficacy of BCG decline with time since vaccination? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2:200-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka, Y., C. T. Morita, Y. Tanaka, E. Nieves, M. B. Brenner, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. Natural and synthetic nonpeptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature 375:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka, Y., S. Sano, E. Nieves, et al.. 1994. Nonpeptide ligands for human gamma delta T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8175-8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsukaguchi, K., K. N. Balaji, and W. H. Boom. 1995. CD4+ alpha beta T-cell and gamma delta T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Similarities and differences in Ag recognition, cytotoxic effector function, and cytokine production. J. Immunol. 154:1786-1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waters, W. R., M. V. Palmer, B. A. Pesch, S. C. Olsen, M. J. Wannemuehler, and D. L. Whipple. 2000. Lymphocyte subset proliferative responses of Mycobacterium bovis-infected cattle to purified protein derivative. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 77:257-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]