Abstract

The airway epithelium represents a primary site for contact between microbes and their hosts. To assess the role of complement in this event, we studied the interaction between the A549 cell line derived from human alveolar epithelial cells and a major nosocomial pathogen, Klebsiella pneumoniae, in the presence of serum. In vitro, we found that C3 opsonization of poorly encapsulated K. pneumoniae clinical isolates and an unencapsulated mutant enhanced dramatically bacterial internalization by A549 epithelial cells compared to highly encapsulated clinical isolates. Local complement components (either present in the human bronchoalveolar lavage or produced by A549 epithelial cells) were sufficient to opsonize K. pneumoniae. CD46 could competitively inhibit the internalization of K. pneumoniae by the epithelial cells, suggesting that CD46 is a receptor for the binding of complement-opsonized K. pneumoniae to these cells. We observed that poorly encapsulated strains appeared into the alveolar epithelial cells in vivo but that (by contrast) they were completely avirulent in a mouse model of pneumonia compared to the highly encapsulated strains. Our results show that bacterial opsonization by complement enhances the internalization of the avirulent microorganisms by nonphagocytic cells such as A549 epithelial cells and allows an efficient innate defense.

The airway epithelium is the largest surface of the respiratory tract and is often the initial site of contact between microbes and their hosts. Through this interaction epithelial cells may have the opportunity to detect and respond to pathogens independently of signals from other cell types of the respiratory system. This is a crucial step for the activation of an efficient inflammatory response and for the recruitment of leukocytes to the lung. However, the capacity of the epithelial cells to detect the respiratory microbial pathogens and directly participate in the defense against them remains poorly investigated.

Respiratory epithelia are coated with a thin layer of airway and alveolar secretions. In the nose, trachea, and bronchi, the secretions are, in part, generated by airway epithelial cells (3, 8). In the distal airways and alveoli, Clara cells and type 2 alveolar cells, respectively, are the predominant secretory epithelial cells (8, 19, 26). Antimicrobial polypeptides and local complement are two of the components of the respiratory secretions that may provide an important early clearance mechanism for pathogens before immune cells are recruited and systemic complement can reach the lung (8, 9, 26, 31). Moreover, the initial phase of inflammatory response to infection involves activation of the humoral innate immune system (in particular, the complement).

Experimental and clinical observations indicate that suitable levels of complement are critical for efficient detection and clearance of the microorganism from the lung. Complement-depleted animals were unable to clear Streptococcus pneumoniae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa from their lungs as efficiently as healthy animals (9). Moreover, certain mannose-binding genotypes of lectin, a key mediator of innate host immunity that activates the complement cascade, have been associated with an increased risk of invasive pneumonia (20). It is reasonable to believe that these observations were made on the basis of the fact that bacterial opsonization by complement promotes adhesion and ingestion of microorganisms by professional phagocytes, including alveolar macrophages resident on the epithelial surface and neutrophils recruited to the lung (29). However, to date the role of complement in the interaction between microbes and the first line of immune innate defense, the airway epithelial cells, has not been described.

To investigate the role of complement in the interaction between the alveolar epithelial cells and bacteria, we used Klebsiella pneumoniae, a major nosocomial pathogen causing pneumonia (17). Pulmonary infections caused by this opportunistic pathogen are characterized by a rapid progressive clinical course complicated by lung abscesses and multilobular involvement which leaves a short time for the establishment of an effective antibiotic treatment in which the first barriers of defense, like the alveolar epithelial cells and complement, might play a crucial role. We observed that complement, specifically C3, enhanced the bacterium-epithelial-cell interaction. This phenomenon was particularly relevant for the poorly encapsulated bacterial strains, which deposited C3 and were internalized by A549 epithelial cells efficiently but showed a marked reduction in their ability to cause pneumonia compared with encapsulated strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and media.

K. pneumoniae clinical isolate 52145R (serotype K2) and its derived serum-resistant avirulent unencapsulated mutant 52K10 were previously described (5). Other K. pneumoniae clinical isolates included in this study were strains 7331, 2056, 5651, 4553, and 2374. Bacterial cells were grown in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C with shaking or solidified with 1.5% agar.

Human reagents and antibodies.

Fresh blood collected from nine healthy volunteers was clotted and centrifuged to obtain normal nonimmune human serum (NHS). NHS was pooled, aliquoted, and frozen at −70°C until its use or incubated at 56°C for 30 min to obtain heat-inactivated human serum (HI-NHS), which was also stored at −70°C. Human C3-deficient serum and human complement component C3 were purchased from Sigma (Madrid, Spain).

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) collected (following standard procedures) (31) from five other human volunteers was centrifuged to remove cells, pooled, concentrated 200-fold by liophilization, dialyzed against distilled water, and stored at −70°C. Calcium (2.6 mM) and magnesium (20 mM) were added back to the samples just before their use. Heat-inactivated BALF (HI-BALF) was obtained as described above for the serum. All human samples were taken after written consent of the participants. They had been informed of the purposes of the study (which had been approved by the Ethics Review Board of the institution).

To obtain soluble recombinant human CD46, an 835-bp DNA fragment comprising the extracellular region of CD46 was amplified by PCR using human CD46 MCP-C2 isoform cDNA as the template (a gift of A. Hirano, Seattle, Wash.) (10) and the following synthetic oligonucleotides: sense strand primer 5′-gaattcCGATGCCTGTGAGGAG-3′ and antisense strand primer 5′-aagcttTATTCCTTCCTCAGGT-3′ (the lowercase letters indicate EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites). The PCR product was cloned in pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands), and the EcoRI-HindIII fragment was subcloned in the pET24b plasmid and sequenced. The His-tagged CD46 protein was produced in Escherichia coli BL-21, extracted from inclusion bodies, and refolded by standard methods. CD46 comprised more than 95% of the refolded protein and was used without further purification. The protein was functional (as assessed by C3b binding or by the binding of monoclonal antibodies sensitive to CD46 denaturation) (data not shown).

Polyclonal antisera against human complement component C3 were developed in goat (Sigma) or in rabbit as described by Albertí et al. (1). Antibodies against human CD35 (CR1), CD21 (CR2), CD11b (CR3), and CD46 (a membrane cofactor protein [MCP]) were supplied by Becton Dickinson (Madrid, Spain).

Determination of CPS production.

Capsular polysaccharide (CPS) production was quantified by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). CPS-containing extracts from 4-ml overnight cultures were obtained by a phenol-water minipreparation method. Phenol was eliminated with chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation (2). Precipitates containing CPS extracts were resuspended in distilled water and used in the inhibition step in the competitive ELISA.

For the ELISA, plates were coated with 1 μg of purified CPS per well. After a blocking step with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), plates were incubated with serial dilutions of CPS extracts and antiserum against CPS. Antibodies bound to the CPS-coated plates were detected with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate. Incubations with antiserum diluted in PBS-1% BSA were carried out at 37°C for 1 h and were always followed by PBS washes. Known amounts of CPS purified by the method of Wilkinson and Sutherland (32) were used to construct a standard curve.

C3 binding to bacterial cells.

Levels of C3 binding to bacteria were analyzed by ELISA or by Western blotting as described previously (1). Bacterial cells were opsonized for 30 or 60 min at 37°C and washed three times with PBS. To disrupt ester bonds between C3 fragments and the bacterial surface, bacterial cells were resuspended in 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.0) containing 1 M NH4OH. After 2 h at 37°C, bacteria were removed by centrifugation and the C3 fragment suspension was collected and processed for the ELISA or Western blotting experiments. For the ELISA, microtiter plate wells were coated with serial dilutions of the C3 suspension in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. After 2 h of incubation with PBS-1% BSA, plates were incubated with anti-human C3, then with alkaline phosphatase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG, and finally with p-nitrophenyl phosphate in 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6)-5 mM MgCl2 to develop alkaline phosphatase. Incubations with antiserum diluted in PBS-BSA were carried out at 37°C for 1 h and were always followed by PBS washes.

For the Western blot experiments, aliquots of C3 fragment suspension (previously reduced and alkylated) were diluted 1:1 in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. Filters were blocked with PBS-1% BSA and incubated sequentially with anti-human C3 (1:1,000) and alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG and developed with BCIP-nitroblue tetrazolium.

Bacterial adhesion and internalization assays.

Monolayers of human lung carcinoma cells A549 (ATCC CCL185) derived from type II pneumocytes were grown to confluence in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum plus penicillin and streptomycin in 24-well tissue culture plates (∼5 × 105 cells per well). For the adhesion assays, A549 cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 with a suspension of 5 ×107 bacterial cells in RPMI medium alone or supplemented with different sources of complement (NHS, HI-NHS, and human C3-deficient serum) (final concentration, 2%). After incubation, wells were washed three times with PBS and adherent bacteria were released by addition of 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and quantified by plating appropriate dilutions on Luria-Bertani agar plates. In the internalization assays, after the incubation of the epithelial cells with the bacterial suspension wells were washed with PBS and then incubated with fresh RPMI medium containing gentamicin (100 μg/ml) to kill extracellular bacteria. At 2 and 24 h after the initial inoculation, an aliquot of the medium was plated to confirm killing of extracellular bacteria and the gentamicin-containing medium was washed again. Epithelial cells were lysed and intracellular bacteria were quantified as described above. Cytotoxicity was estimated by assessing the ability of epithelial cells from replicate wells to exclude trypan blue.

For the blockade of complement-mediated internalization experiments, 106 preopsonized bacterial cells were coincubated with A549 in the presence of purified CD46 (100 μg/ml) or BSA at the same concentration. After 1 h of incubation, intracellular bacteria were quantified as described above.

Cytokine activation of monolayers.

A549 monolayers were stimulated by the addition of interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) (250 U/ml) to the medium and incubated for 18 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Controls wells were incubated with medium alone for 18 h under identical conditions. Supernatants from IL-1α-stimulated wells and unstimulated wells were examined for C3 production as described above.

Murine model of pneumonia.

Male (16 to 20 g) ICR:CD-1 mice (Harlan Ibérica, Barcelona, Spain) were anesthetized and intubated intratracheally using a blunt-ended feeding needle. Approximately 106 CFU of K. pneumoniae from an early log-phase broth culture were suspended in 50 μl of Ringer's solution and inoculated through the needle. The lungs from animals were aseptically removed and homogenized for quantitative bacterial cultures.

All animal experiments were done according to institutional and national guidelines and approved by the Experimental Animal Committee of the institution.

Microscopy.

Monolayers of A549 epithelial cells infected as described above or a tissue block of lungs dissected from infected animals was washed, fixed with glutaraldehyde, and processed for transmission electron microscopy as described previously (13). For the immunohistochemical analysis, biopsies of human lung were fixed in 10 vol. of 10% neutral buffered formalin, imbedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4- to 6-μm intervals. Tissue sections were incubated with human anti-CD46 and developed following standard techniques (18).

Flow cytometry.

Cells (106) resuspended in 50 μl of PBS were incubated 30 min at room temperature with specific antibodies labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate. After washing with PBS, the samples were analyzed on an Epics XL apparatus (Beckman Coulter, Izasa, Barcelona, Spain).

Statistical analysis.

The statistical significance of the data obtained in at least three independent experiments with two replicates for each sample in each experiment was determined by two-tailed t test. Values were considered significantly different when P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of complement opsonization on bacterial internalization by A549 epithelial cells.

To study directly the role of complement activation on the bacterium-epithelial cell interaction, we investigated the ability of the A549 epithelial cells to attach and internalize the wild-type virulent strain 52145R and its derived unencapsulated serum-resistant avirulent mutant 52K10 in the presence or absence of complement (Fig. 1).

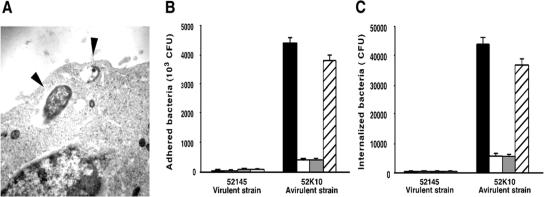

FIG. 1.

Attachment and internalization of K. pneumoniae by A549 alveolar epithelial cells. (A) Transmission electron micrograph of an A549 human lung epithelial cell infected by the avirulent K. pneumoniae strain 52K10. Arrowheads indicate bacterial cells within vacuoles. (B and C) Mean numbers of K. pneumoniae avirulent unencapsulated mutant 52K10 and its parental virulent strain 52145 attached (B) or internalized (C) by human A549 epithelial cells in the presence of nonimmune human serum (black bars), heat-inactivated serum (white bars), human C3-deficient serum (grey bars), and human C3-deficient serum complemented with purified human C3 (hatched bars). The data are the means ± standard deviations (SD) of the results of at least three independent experiments (P < 0.01 for comparison between 51245 and 52K10 and for comparison between black and hatched bars versus white and grey bars only for the avirulent strain 52K10 [two-tailed t test]).

The avirulent strain 52K10 attached and was internalized by A549 epithelial cells with a high level of efficiency compared to the virulent strain 52145R. Electron microscopy showed that the avirulent strain 52K10 was within vacuole-like structures within the culture-grown A549 epithelial cells (Fig. 1A). The avirulent strain showed approximately 10-fold greater adhesion and internalization than the virulent strain (Fig. 1B and C, respectively). We quantified the number of attached and internalized bacteria after coincubation of A549 epithelial cells and both strains in the presence of NHS (2% final concentration). The number of avirulent bacterial cells attached and internalized by A549 epithelial cells was up to a log-fold higher when incubated with NHS than without it. This effect appeared due to the presence of an intact complement system, since incubation of the bacterial cells and A549 epithelial cells in the presence of HI-NHS or C3-deficient serum did not increase the number of bacteria attached or internalized by the human cells. Furthermore, a C3-deficient serum reconstituted with human purified C3 showed attachment and internalization rates similar to those obtained with NHS. The efficiency of the attachment of virulent bacterial cells and uptake by A549 epithelial cells in the presence of complement did not increase compared to the efficiency observed without serum or with HI-NHS and C3-deficient serum.

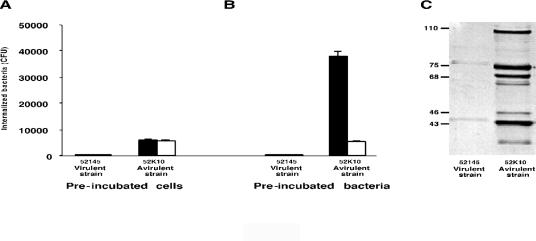

These results indicate that the presence of an intact complement system, particularly the presence of the pivotal component C3, augments attachment and internalization of avirulent bacteria by A549 epithelial cells. Because this enhancement was only observed with the avirulent strain and not with the virulent strain, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the increased efficiency of internalization observed when bacteria were coincubated with the A549 epithelial cells and NHS was due to the opsonization of the bacteria rather than to an alteration of A549 epithelial cell surface molecule expression. To investigate this hypothesis we preincubated A549 epithelial cells with NHS or C3-deficient serum and subsequently with both bacterial strains. In these experiments, we did not observe an augmentation of the intracellular bacteria, indicating an effect of C3 activation on the bacterium rather than on the epithelial cell (Fig. 2A). Preopsonization of the bacteria followed by the internalization assay in serum-free conditions confirmed our hypothesis (Fig. 2B). The internalization rate of the avirulent strain increased after preincubation of the bacterial cells with NHS but not when they were preopsonized with C3-deficient serum. The conditions used to preincubate the bacteria led to deposition of the 105-kDa α′ chain of C3b, the 75-kDa β chain common to C3b, and the 68-kDa chain of iC3b on the bacterial surface of the avirulent strain (Fig. 2C). However, we did not detect C3 deposited on the virulent strain. These results indicate that the virulent strain did not exhibit an increased rate of internalization by A549 epithelial cells in the presence of NHS, because complement failed to opsonize it; consequently, no augmentation of the internalization by A549 epithelial cells was expected (even in the presence of an intact complement).

FIG. 2.

The effect of preincubation with nonimmune human serum. (A and B) The effect of preincubation of human A549 epithelial cells (A) or bacterial cells (B) with NHS (black bars) or C3-deficient serum (white bars) on the internalization of K. pneumoniae virulent strain 52145R and its derived avirulent mutant 52K10 by human A549 epithelial cells. (C) Western blot analysis of C3 fragments deposited on each strain after preincubation with NHS. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left side of the panel.

Role of the complement system present in the lung.

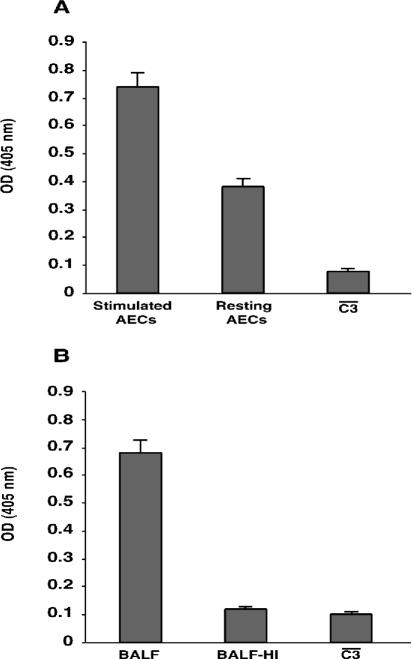

Our results using NHS indicate that C3 opsonic fragments deposited on the bacterial surface interact with A549 epithelial cells and facilitate bacterial uptake into the cells. However, a prerequisite for complement having a role in respiratory tract infections is the ability to opsonize bacteria by the human lung fluids. Alveolar type II epithelial cells synthesize and secrete specific components of the classical and alternative pathways and are a major source of complement in the lung (19). To determine whether A549 epithelial cell complement synthesis could also contribute to the opsonization of K. pneumoniae, we incubated bacteria with the supernatants of A549 epithelial cell cultures stimulated with IL-1α or not stimulated. It has been reported that IL-1α enhances the synthesis of complement components (particularly C3) by A549 epithelial cells (23). We confirmed that A549 epithelial cells exposed to IL-1α produced fivefold more C3 than resting cells (means of concentrations, 29 versus 6 ng/ml). In consequence, bacteria incubated with supernatants from stimulated A549 epithelial cells activated complement and deposited C3 more efficiently than those incubated with supernatants from resting epithelial cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Effect of the presence of local complement on bacterial opsonization. (A and B) C3 deposited on the avirulent K. pneumoniae strain 52K10 after preopsonization with supernatant of cultured A549 epithelial cells (AECs) (A) or BALF (B). C3 binding was measured by ELISA; values represent arbitrary optical densities at 405 nm. Significantly more C3 was bound to bacteria opsonized with the supernatant of IL-1α-stimulated cells and with BALF than to bacteria opsonized with the supernatant of resting cells or with heat-inactivated BALF (P < 0.01 [two-tailed t test]). Data are the means ± SD of the results of at least three independent experiments.

We also determined whether the local complement system in the human lung has a role in the opsonization of the bacteria (and, in consequence, in the internalization by A549 epithelial cells) by incubation of the bacteria with human BALF. Incubation of the avirulent bacteria with BALF (10% final concentration) led to the activation of complement and binding of C3 on the bacterial surface (Fig. 3B).

Taken all together, the data of these experiments show that the epithelial cell complement synthesis and the local complement system present in the human lung fluids are sufficient to opsonize bacteria and therefore to facilitate internalization by human A549 epithelial cells.

MCP mediates bacterial internalization by A549 epithelial cells.

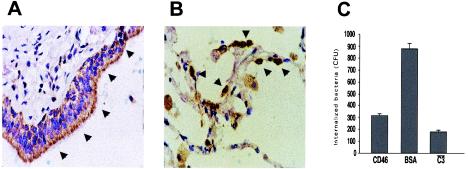

Our data imply that C3 opsonic fragments deposited on the bacterial surface interact with an alveolar epithelial receptor and mediate bacterial uptake into the cells. We examined (by flow cytometry with specific antibodies) the cell surface expression of several complement receptors on the A549 epithelial cells. We observed that MCP or CD46 was strongly expressed; however, we did not detect expression of CR1, CR2, or CR3 (data not shown). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis of normal human lung tissue confirmed the expression of CD46 on the apical area of the bronchoepithelial cells (Fig. 4A) and also on the pneumocytes (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

CD46 expression on respiratory tract epithelial cells and blockade of bacterial complement-mediated internalization by A549 alveolar epithelial cells with purified CD46. (A and B) Strong CD46 expression (arrowheads) on the human bronchoepithelial cells and on alveolar epithelial cells, respectively. (C) Quantification of the number of intracellular bacteria preopsonized with NHS after coincubation with A549 in the presence of purified CD46 (100 μg/ml) or BSA (100 μg/ml) or preopsonized with human C3-deficient serum (P < 0.01 for comparison between blockade with CD46 and BSA [two-tailed t test]). Data are the means ± SD of the results of at least three independent experiments.

To investigate whether CD46 mediates uptake of K. pneumoniae into the A549 epithelial cells, we used purified human CD46 to block the interaction between C3 opsonic fragments deposited on the bacterial surface and epithelial cell surface receptors for C3. Internalization of preopsonized K. pneumoniae 52K10 by A549 epithelial cells was reduced up to 60% in the presence of CD46, whereas the presence of BSA (used as a control) did not affect the rate of internalization (Fig. 4C).

The results of these experiments suggest that CD46 is a lung epithelial receptor that promotes internalization of opsonized K. pneumoniae.

Avirulent K. pneumoniae clinical isolates were internalized efficiently but fail to grow into A549 epithelial cells.

We next investigated whether the differences in the internalization by A549 epithelial cells and deposition of C3 correlate with differences in the abilities of the organisms to cause pneumonia.

We previously demonstrated that the laboratory acapsular mutant 52K10 failed to cause pneumonia in a mouse model (5), although (as we have demonstrated here) the mutant strain deposits C3 and enters efficiently into the A549 epithelial cells compared to the virulent parent strain 52145R. These results suggest that entry into epithelial cells does not promote subsequent invasive infection but rather represents a mechanism to contain infection. To extend these results to other strains, we quantified the C3 deposition on highly encapsulated K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (mean, 283 fg of CPS/CFU; range, 210 to 400) and on poorly encapsulated isolates (mean, 18 fg of CPS/CFU; range, 10 to 30). We detected an inverse relationship between the amount of CPS produced by the strain and its capacity to deposit C3 (Fig. 5A). By contrast, poorly encapsulated strains were internalized by A549 epithelial cells more efficiently that encapsulated strains. Thus, in the absence of complement we recovered 2,310 to 4,680 intracellular microorganisms of K. pneumoniae strains that produce small amounts of capsule but only 430 to 655 microorganisms of the encapsulated strains. As occurred with the unencapsulated mutant, moreover, C3 enhanced the internalization of the poorly encapsulated strains (in contrast with the highly encapsulated strains that show similar rates of internalization to those observed without complement) (Fig. 5B). We studied recovery over time of intracellular K. pneumoniae from infected A549 epithelial cells. Viable intracellular bacteria declined in numbers over time, and after 24 h only 2 to 8% of the bacteria recovered after 2 h of inoculation were viable. After 24 h of incubation, we determined the viability of the epithelial cells by measuring the number of cells that failed to exclude trypan blue. More than 90% of the epithelial cells remained viable, suggesting that epithelial cell death accounted for some, but not all, of the decline in the number of intracellular bacteria. Thus, intracellular bacteria were not able to multiply into the epithelial cells and after 24 h of incubation 92% of the bacteria were nonviable.

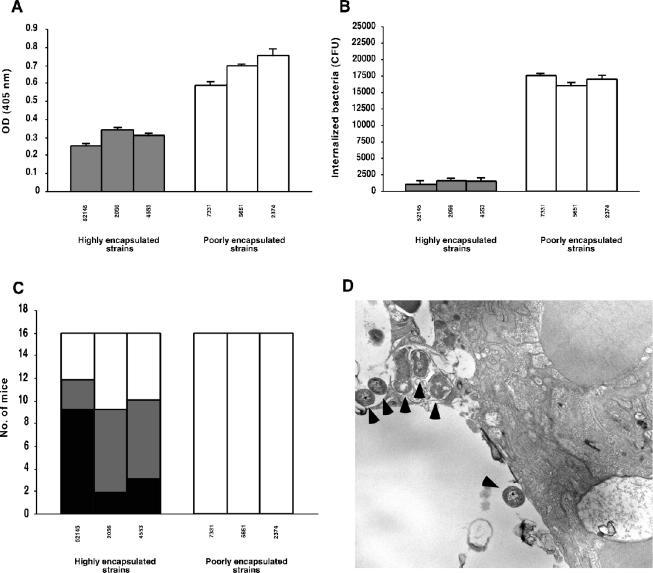

FIG. 5.

Correlation between C3 deposition, internalization by A549 alveolar epithelial cells, and the ability to cause pneumonia of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. Poorly encapsulated strains bound C3 (as measured by ELISA; panel A) and were internalized by A549 epithelial cells in the presence of complement significantly more efficiently than the highly encapsulated strains (B) (P < 0.03). Data are the means ± SD of the results of at least three independent experiments. (C) By contrast, poorly encapsulated strains were avirulent in a mouse model of pneumonia in which at least half of the animals infected with the highly encapsulated strains died or presented positive-testing lung cultures. White bars, live animals with negative-testing lung culture; grey bars, animals with positive-testing lung culture; black bars; deaths. Bacterial culture experiments were performed for all animals at day 7 postinfection. (D) Transmission electron micrograph showing a lung section from a mouse infected with an avirulent strain 24 h postinfection. Bacterial cells (arrowheads) adhered to alveolar epithelial cells or within vacuole-like structures within the epithelial cell.

Finally, we studied experimental pneumonia induced by strains with different degrees of encapsulation. The mice were infected with similar numbers of microorganisms (approximately 106 CFU), so differences in the ability to cause pneumonia between the strains were not due to the inoculum. At 7 days after inoculation, only mice infected with highly encapsulated isolates died or presented positive-testing lung cultures (Fig. 5C). We confirmed (by histological examination) the presence of inflammation with neutrophil infiltration and bacteria in their lungs (data not shown). We studied the lower respiratory tract infection caused by the poorly encapsulated strains over time. We observed that all the animals had bacteria in their lungs the first day. Bacteria reached the alveolus and were adherent or within the epithelial cells within vacuole-like structures similar to those seen in culture-grown A549 epithelial cells (Fig. 5D). However, none of the animals presented bacteria in their lungs after 2 days (data not shown).

All together, these in vivo results suggest that internalization of bacteria by lung epithelial cells might represent a strategy of the host to avoid pneumonia produced by the presence of K. pneumoniae. Furthermore, these results suggest that in addition to complement-mediated phagocytosis induced by alveolar macrophages and recruited neutrophils, bacterial opsonization by complement might modulate the bacterial interaction with lung epithelial cells.

DISCUSSION

In contrast with that seen with other major environmental interfaces, including the skin and the urinary tract, host defense in the lung is unique. The objective in the alveoli is sterility rather than the maintenance of normal floras; however, the number of resident inflammatory leukocytes available for immediate control of infection is relatively small. Microorganisms that elude the upper respiratory mechanisms of defense and reach the alveolar space interact with the alveolar epithelium. Thus, the epithelial barrier itself represents the first line of contact with the pathogens. Recognition of bacteria by the epithelial cells to trigger the inflammatory response and to induce recruitment of additional leukocytes to the airspace may be critical.

In this study, we have shown that recognition of bacteria by A549 epithelial cells is dependent on the presence of a host protein, namely, complement C3. It has been reported that specific host proteins mediate the interaction of many other pathogens with the eukaryotic cells. S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (all typical respiratory pathogens) anchor to airway epithelial cells by binding to the platelet-activator factor receptor (6, 27), to the hyaluronic binding protein CD44 (21), or to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (16), respectively. Other microorganisms are recognized by the eukaryotic cells via Toll-like receptors through pathogen-associated molecular patterns in a process that requires the presence of CD14, a soluble component present in plasma (30). It would appear that A549 epithelial cells use host C3 to interact efficiently with K. pneumoniae.

Although complement levels in the lung are low, we have demonstrated that there is a functional complement system present in the lung that aids the opsonization of bacteria.

On one hand, we have shown that type II alveolar epithelial cells, one of the major sources of complement components in the lung (19), produce sufficient C3 to opsonize K. pneumoniae. Furthermore, the synthesis of the C3 increased markedly after stimulation with IL-1-α; therefore, we observed that stimulated A549 epithelial cells opsonized bacteria more efficiently than resting cells. These results suggest that under inflammatory conditions, the higher concentration of C3 produced by the epithelial cells might enhance internalization of bacteria in vivo.

On the other hand, the lavage samples were able to support significant complement activation (as assessed according to levels of C3 deposition on the bacterial surface). Similar results were reported by Watford et al. with Streptococcus agalactiae (31). It is possible, moreover, that during bacterial pneumonia, complement components synthesized by the recruited neutrophils increase the normal levels of C3 in the lungs. Therefore, levels of C3 deposition might exceed those observed with healthy human BALF. All together, our results show that levels of C3 in the lung are sufficient to support bacterial opsonization during infection.

We investigated whether the mechanism for C3-mediated uptake of opsonized K. pneumoniae by A549 epithelial cells occurs via a receptor-ligand interaction. C3 opsonic fragments deposited on the bacterial surfaces are recognized by receptors displayed by the phagocytic cells (typically CR1, CR2, and CR3). However, we did not detect expression of these receptors with the A549 epithelial cells. By contrast, CD46 or MCP that specifically interacts with C3b is present on the respiratory epithelial cells, suggesting that it might be a candidate receptor. Furthermore, purified soluble human CD46 inhibited the internalization of opsonized bacteria. Thus, this purified receptor has the ability to block the interaction between the opsonized bacteria and A549 epithelial cells. These observations indicate that the adhesion and internalization of opsonized K. pneumoniae are mediated by a complement receptor, probably CD46. Other microorganisms exploit CD46 or CD46-like molecules to gain entry into epithelial cells. Uropathogenic E. coli activates complement, depositing C3 on its surface and enabling it to enter uroepithelial cells via Crry, a functional homologue of CD46 in the mouse (24). Adherence of S. pyogenes to keratinocytes is also mediated by CD46 (15). Our results show that A549 epithelial cells internalize complement C3-opsonized K. pneumoniae via CD46.

The biological significance of the internalization of certain bacterial pathogens by nonphagocytic cells (such as epithelial cells) is not known. Previous studies have shown that internalization of certain respiratory pathogens by epithelial cells does not promote subsequent invasive infection but rather represents a mechanism to contain infection (4, 11, 16, 22, 25). This study again shows an inverse relationship between the ability to cause pneumonia and the capacity to enter into lung epithelial cells. Poorly encapsulated strains deposited more C3, were internalized efficiently by A549 epithelial cells, and were completely avirulent in mice compared to highly encapsulated strains. An explanation for these observations is that deposition of complement opsonic fragments on the surface of the microorganisms conveys to the phagocytic cells the ability to recognize and phagocyte K. pneumoniae efficiently (5). An additional explanation for our results is that complement promotes uptake of the avirulent strains by the lung epithelial cells, since internalized bacteria did not proliferate into the epithelial cells but rather exhibited a steady decline in viability.

The results of our experiments indicate that C3 deposited on the bacteria promotes the uptake of the microorganism by A549 epithelial cells in a fashion similar to that normally carried out by traditional phagocytes even though these cells are not considered phagocytic (12). Thus, as occurs in the interaction with alveolar macrophages (in which CPS blocks the phagocytosis of the bacteria) (5), CPS acts as a virulence factor, preventing complement deposition and the ingestion of the bacteria by the epithelial cells.

It has been reported that interaction of certain pathogens with the epithelial cells results in the release of cytokines and chemokines by the epithelial cells (7, 14, 28). We have observed that internalization of K. pneumoniae results in the up-expression of IL-8 and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 by the A549 epithelial cells (J.A. Bengoechea, personal communication). Therefore, internalization of K. pneumoniae by epithelial cells mediated by C3 might represent an efficient mechanism to trigger the inflammatory response and to induce recruitment of additional inflammatory cells to the airspace. In these cases, the epithelial cells would function like “sentinels” of the enormous surface area to defend.

In summary, our in vitro results demonstrate that internalization of K. pneumoniae by human A549 epithelial cells represents a mechanism to contain infection. The presence of an intact complement cascade promotes the uptake and consequently the clearance of the bacteria by the A549 epithelial cells. Our results do not exclude the possibility that in vivo, other actions of the complement (for example, complement-mediated opsonophagocytosis by alveolar macrophages) are critical and essential for clearance of the microorganism from the lung. However, our results suggest that C3-mediated uptake by the lung epithelial cells might be a contributory factor. Variability in the capacity of the host to produce C3 or in the ability of the bacteria to activate C3 might influence not only the clearance of the microorganism by professional phagocytes but also the recognition of the bacteria by the first line of defense, the epithelial cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Sauleda for providing human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, M. Pocoví for technical assistance in electron microscopy, and J. Pons for technical advice in flow cytometry.

This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III through grants from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (02-0977), Red Española de Investigación en Patología Infecciosa (REIPI C03/14), and Red Respira (RTIC C03/11).

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertí, S., D. Álvarez, S. Merino, M. T. Casado, F. Vivanco, J. M. Tomás, and V. J. Benedí. 1996. Analysis of complement C3 deposition and degradation on Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 64:4726-4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albertí, S., J. Imperial, T. J. M., and V. J. Benedí. 1991. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide extraction in silica gel-containing tubes. J. Microbiol. Methods 14:63-69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, A. M., P. Ewan, and T. Ganz. 1999. Innate antimicrobial activity of nasal secretions. Infect. Immun. 67:3267-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortés, G., D. Álvarez, C. Saus, and S. Albertí. 2002. Role of lung epithelial cells in defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 70:1075-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortés, G., N. Borrell, B. de Astorza, C. Gómez, J. Sauleda, and S. Albertí. 2002. Molecular analysis of the contribution of the capsular polysaccharide and the lipopolysaccharide O side chain to the virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a murine model of pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 70:2583-2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cundell, D. R., N. P. Gerard, C. Gerard, I. Idanpaan-Heillila, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1995. Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activated human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature 377:435-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frick, A. G., T. D. Joseph, L. Pang, A. M. Rabe, J. W. St. Geme III, and D. C. Look. 2000. Haemophilus influenzae stimulates ICAM-1 expression on respiratory epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 164:4185-4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganz, T. 2002. Antimicrobial polypeptides in host defense of the respiratory tract. J. Clin. Investig. 109:693-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross, G. N., S. R. Rehm, and A. K. Pierce. 1978. The effect of complement depletion on lung clearance of bacteria. J. Clin. Investig. 62:373-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano, A., S. Yant, K. Iwata, J. Korte-Safarty, T. Seya, S. Nagasawa, and T. C. Wong. 1996. Human cell receptor CD46 is down regulated through recognition of a membrane-proximal region of the cytoplasmic domain in persistent measles virus infection. J. Virol. 70:6929-6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulse, M. L., S. Smith, E. Y. Chi, A. Pham, and C. E. Rubens. 1993. Effect of type III group B streptococcal capsular polysaccharide on invasion of respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 61:4835-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isberg, R. R. 1991. Discrimination between intracellular uptake and surface adhesion of bacterial pathogens. Science 252:934-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruskal, B. A., K. Sastry, A. B. Warner, C. E. Mathieu, and R. A. B. Ezekowitz. 1992. Phagocyte chimeric receptors require both transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains from the mannose receptor. J. Exp. Med. 176:1673-1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murdoch, C., R. C. Read, Q. Zhang, and A. Finn. 2002. Choline-binding protein A of Streptococcus pneumoniae elicits chemokine production and expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD54) by human alveolar epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1253-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada, N., M. K. Liszewski, J. P. Atkinson, and M. Caparon. 1995. Membrane cofactor protein (CD46) is a keratinocyte receptor for the M protein of the group A streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2489-2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pier, G. B., M. Grout, T. S. Zaidi, J. C. Olsen, L. G. Johnson, J. R. Yankaskas, and J. B. Goldberg. 1996. Role of mutant CFTR in hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis patients to lung infections. Science 5:64-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podschum, R., and U. Ullman. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prophet, E. B., B. Mills, J. B. Arrington, and L. H. Sobin (ed.). 1992. Laboratory methods in histotechnology. American Registry of Pathology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Rothman, B. L., A. W. Despins, and D. L. Kreutzer. 1990. Cytokine regulation of C3 and C5 by the human type II pneumocyte cell line, A549. J. Immunol. 145:592-598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy, S., K. Knox, S. Segal, D. Griffiths, C. E. Moore, K. I. Welsh, A. Smarason, N. P. Day, W. L. McPheat, D. W. Crook, A. V. Hill, and Oxford Pneumococcal Surveillance Group. 2002. MBL genotype and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: a case-control study. Lancet 359:1569-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrager, H. M., S. Alberti, C. Cywes, G. J. Dougherty, and M. R. Wessels. 1998. Hyaluronic acid capsule modulates M protein-mediated adherence and acts as a ligand for attachment of group A streptococcus to CD44 on human keratinocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1708-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrager, H. M., J. G. Rheinwald, and M. R. Wessels. 1996. Hyaluronic acid capsule and the role of streptococcal entry into keratinocytes in invasive skin infection. J. Clin. Investig. 98:1954-1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith, B. L., and M. K. Hostetter. 2000. C3 as substrate for adhesion of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 182:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Springall, T., N. S. Sheerin, K. Abe, V. M. Holers, H. Wan, and S. H. Sacks. 2001. Epithelial secretion of C3 promotes colonization of the upper urinary tract by Escherichia coli. Nat. Med. 7:801-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens, D. S., P. A. Spellman, and J. S. Swartley. 1993. Effect of the (alpha 2→8)-linked polysialic acid capsule on adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human mucosal cells. J. Infect. Dis. 167:475-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strunk, R. C., D. M. Eidlen, and R. J. Mason. 1988. Pulmonary alveolar type II epithelial cells synthesize and secrete proteins of the classical and alternative complement pathways. J. Clin. Microbiol. 81:1419-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swords, W. E., B. A. Buscher, L. K. Ver Steeg, A. Preston, W. A. Nichols, J. N. Weiser, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 2000. Non-typable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells via an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 37:13-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swords, W. E., M. R. Ketterer, J. Shao, C. A. Campbell, J. N. Weiser, and M. A. Apicella. 2001. Binding of the non-typable Haemophilus influenzae lipooligosaccharide to the PAF receptor initiates host cell signalling. Cell. Microbiol. 3:525-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Underhill, D. M., and A. Ozinsky. 2002. Phagocytosis of microbes: complexity in action. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:825-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Underhill, D. M., and A. Ozinsky. 2002. Toll-like receptors: key mediator of microbe detection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watford, W. T., A. J. Ghio, and J. R. Wright. 2000. Complement-mediated host defense in the lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 279:790-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilkinson, J. F., and I. W. Sutherland. 1971. Chemical extraction methods of microbial cells. Methods Microbiol. 5:345-383. [Google Scholar]