Abstract

Background:

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has been linked with oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant defense. A connection has been established between diabetes and periodontal disease.

Aim:

The aim of present study was to compare salivary total antioxidant capacity of type 2 DM patients and healthy subjects with and without periodontal disease.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 120 subjects consisting of 30 type 2 DM patients with periodontal disease; 30 type 2 DM patients without periodontal disease; 30 healthy subjects with periodontal disease; 30 healthy subjects without periodontal disease were included in the study. After clinical measurement and samplings, total antioxidant capacity in saliva of type 2 diabetic and healthy subjects were determined, and the data were tested by non-parametric tests. Total antioxidant capacity of the clinical samples was determined spectrophotometrically.

Results:

The mean salivary total antioxidant capacity was lowest in diabetic patients with periodontitis.

Conclusion:

Total antioxidant capacity is inversely proportional to the severity of inflammation and can be used as an useful marker of periodontitis in healthy and diabetic patients.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Diabetes mellitus, Free radicals, Periodontitis, Total antioxidant capacity

Introduction

Periodontal disease, a chronic infectious inflammatory disease characterized by the destruction of the tooth-supporting structures, is the most prevalent microbial diseases of mankind. It is initiated by the complex micro biota found as dental plaque, a complex microbial biofilm, and tissue destruction is largely mediated by an abnormal host response to specific bacteria and their products.[1] Susceptibility appears to be due to a phenotype characterized by an exaggerated, “hyper-inflammatory” response to the colonizing bacteria.[2] The aberrant response is characterized by exaggerated inflammation, involving the release of excess proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the hyper-active/reactive neutrophils. These neutrophils following chemo attraction from the peripheral blood to the periodontal tissues, generate ROS both spontaneously and following stimulation of Fcγ-receptors or toll-like receptors on the neutrophil surface by their respective ligands.[3,4]

A growing body of evidence implicates oxidative stress in the pathobiology of chronic periodontitis. Several studies demonstrated increased levels of biomarkers for tissue damage, by ROS in periodontitis patients relative to controls.[5–7] In response to oxidative stress, antioxidant enzymes appear up-regulated in inflamed periodontal tissues[5,8] and in gingival crevicular fluid, where levels correlate inversely with pocket depth.[9] Furthermore, extracellular antioxidant scavengers are depleted both individually[10] as well as in terms of total antioxidant activity.[5,11] Collateral host-tissue damage occurs due to the elevated levels of ROS generated by neutrophils during the inflammatory response to both microbial plaque and plaque-induced tissue damage. This is induced both directly, via oxidation of vital tissue components as well as indirectly, via the activation of redox-sensitive gene transcription factors like nuclear factor k-B, which in turn leads to downstream proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production. The resultant periodontal inflammation creates a low-grade inflammatory response detectable within the peripheral vasculature.[12]

Saliva possesses a wide range of antioxidants including uric acid, vitamin C, reduced glutathione, oxidized glutathione, and others.[13] Such antioxidants work in concert, and total antioxidant capacity may be the most relevant parameter for assessing the defense capabilities.[11] Periodontitis has been recognized as a risk factor for certain systemic diseases where low-grade inflammation within the peripheral circulation is associated with the etiology or progression of the disease. These manifestations of increased oxidative stress provide potential mechanisms whereby periodontal inflammation may impact upon systemic inflammatory status. Associations have been demonstrated repeatedly between periodontitis and type-2 diabetes,[14] cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular disease.[15,16] Subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) are 2.8 times more likely to have destructive periodontal disease[4] and 4.2 times more likely to have significant alveolar bone loss[17] compared to systemically healthy subjects. Periodontal disease was proposed to be the sixth complication of DM.[18] Conversely, the presence of periodontitis may exert a negative impact on metabolic risk status in type 2 diabetes patients. Periodontal inflammation has been associated with impaired fasting glucose and is an independent predictor of mortality from ischemic heart disease. However, the nature of the biological relationship between periodontitis and type 2 DM remains unclear.[19] Enhanced oxidative stress was observed in patients with diabetes, resulting in hyper-inflammatory state.[20] Hyperglycemia leads to excess ROS production which stimulates NADPH oxidase, principally in neutrophils.[21] Disruption of redox balance results in stimulation of cell-signaling pathways associated with inflammation, dysregulation of insulin signaling, and development of diabetic complications.[22]

The relationship between DM, periodontal disease, and salivary antioxidant status has not been clarified. We hypothesized that the diabetic state would reduce the salivary antioxidant capacity of subjects and, further, that this antioxidant impairment may help to explain the association between diabetes and inflammatory periodontal disease. The aim of this paper was to estimate and compare the total antioxidant capacity in saliva of type 2 diabetes and healthy subjects with and without periodontal disease.

Materials and Methods

A total of 120 subjects inclusive of both genders, between the age group 40-65 years who reported to the Department of Periodontics, A.B. Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Sciences, Mangalore and from the diabetic clinic of K.S. Hegde Medical Academy, Mangalore were selected by simple random sampling method and were included in the study. Ethical committee of the institute approved the study. Oral and written consent was obtained from the participants of the study. The total duration for the study was 6 months from January 2008 to June 2008.

Sixty patients with type 2 DM and no other systemic disease that could affect periodontal status participated in this cross-sectional study. Of these, group 1 included 30 type 2 diabetic patients with periodontal disease (17 female and 13 male) and group 2 included 30 type 2 diabetic patients without periodontal disease (14 female and 16 male).

Patients with diabetes were those consecutively referred during medical care visits from an outpatient diabetic clinic. Patients with diabetes were diagnosed as having type 2 diabetes using American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria.[23] These patients were not under any oral hypoglycemic agents and/or insulin therapy (fresh cases).

In addition, 60 systemically healthy subjects, of which, 30 healthy subjects with periodontal disease (18 female and 12 male) (group 3) and 30 healthy subjects without periodontal disease (15 male and 15 female) (group 4 – control group) were recruited from those patients seeking dental treatment at the Department of Periodontics, A.B. Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Sciences, Mangalore.

Patients were excluded if they had aggressive periodontitis, <14 teeth present, history of antibiotic therapy within the preceding 3 months, periodontal treatment within the last 6 months smokers, on vitamin supplements, obese, and under insulin therapy/oral hypoglycemic medication.

Dental examination

Clinical periodontal parameters, including plaque index, probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), and bleeding on probing (BOP) were assessed. All clinical examinations were carried out by a single examiner, who was trained, calibrated, and masked to the systemic condition of the patient. Each tooth was measured and examined for PD in millimeters and CAL in millimeters at six sites per tooth (mesio-buccal, buccal, disto-buccal, mesio-lingual, lingual, disto-lingual) using a Williams graduated periodontal probe. Dental plaque was scored as being present or absent at four points (mesial, buccal, lingual, and distal) on each tooth. BOP was assessed at the six sites at which PD was determined and was deemed positive if it occurred within 15 s of probing. BOP was expressed as the percentage of sites showing bleeding. Periodontal health was defined as the absence of gingival pockets ≥4 mm and absence of attachment loss ≥3 mm with no BOP. Periodontal disease was defined as two or more tooth sites with PD ≥ 4 mm or CAL of 4 mm that bled on probing.[24]

Saliva sampling

All saliva samples were obtained in the morning after an over-night fast. The subjects were requested not to drink (except water) or chew gum for the same period and abstention was checked prior to biologic sample collection.[11]

For the collection of saliva, the subject was seated in the coachman's position, head slightly down and was asked not to swallow or move his tongue or lips during the period of collection.[25] Whole saliva samples were obtained by expectorating into disposable tubes prior to clinical measurements, the time period for sample collection was recorded in minutes. The collection time was 5 min and the flow rate was calculated as ml/min. Saliva samples were centrifuged immediately to remove cell debris (× 1000 g for 10 min at 4°C). The supernatant was removed and stored in small aliquots at 80°C until analysis.[26]

Measurement of total antioxidant capacity

The total antioxidant capacity of saliva was evaluated using the spectrophotometric assay. The method is based on the principle that, when a standardized solution of Fe-EDTA [Iron- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid] complex reacts with hydrogen peroxide by a Fenton-type reaction, it leads to the formation of hydroxyl radicals (OH). These ROS degrade benzoate, resulting in the release of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). Antioxidants from the added sample of human fluid cause suppression of the production of TBARS. This reaction can be measured spectrophotometrically and the inhibition of color is development defined as the antioxidant capacity. No single method is considered “gold standard” for total antioxidant determination, suggesting that many comparable methods can be used. Although Randox method has been used frequently for estimation of total antioxidant capacity, the TBARS method also gives comparable results.[27]

Statistical analysis

The statistical comparison of the mean values of periodontal parameters, systemic related parameters, total salivary antioxidants and salivary flow rate with respect to the three study groups and one control group was evaluated using one-way ANOVA, Kruskal – Wallis H test (Nonparametric analysis of ANOVA test), Multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA), Tukey's Post Hoc Test with SPSS data processing software version 17.0. A value of P < 0.01 was considered to be significant.

Results

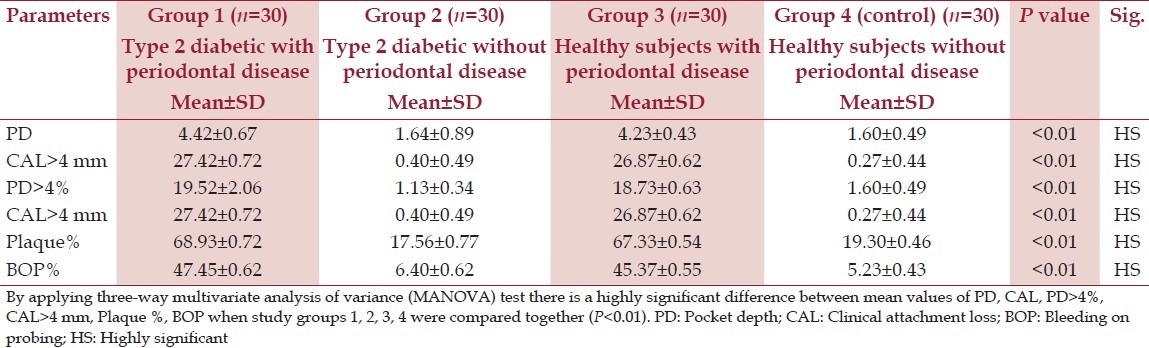

Table 1 displays the clinical periodontal variables in the study groups. As expected mean probing depth (PD) and clinical attachment level (CAL) were higher in diabetic patients with periodontal disease (group 1) when compared with other groups (group 2, 3, and 4) (P < 0.01). Mean PD in group 1 was 4.42 mm when compared with group 2 and group 4 where the values were 1.64 and 1.60 mm, respectively, which were statistically highly significant (P < 0.01). Also, group 1 exhibited a higher percentage of sites with PD ≥ 4 mm, sites with CAL ≥ 4 mm, sites with plaque, and sites exhibiting BOP in comparison with the other three groups which were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Periodontal parameters among the study groups

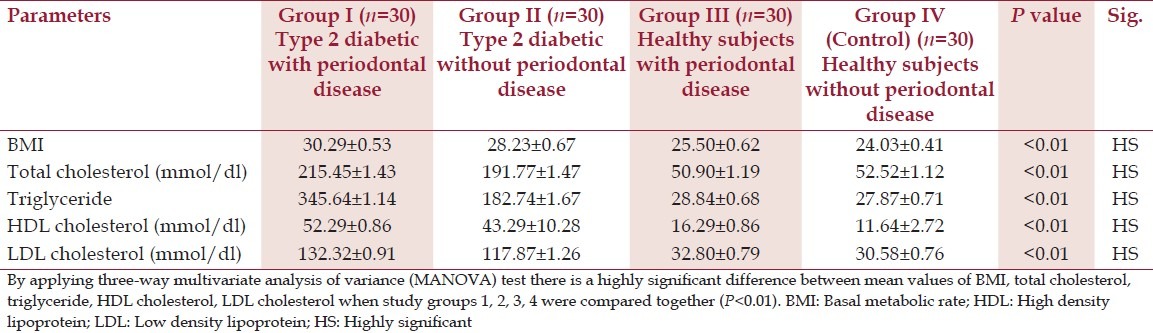

Significant differences in basal metabolic rate (BMI), was not found between the diabetes groups. (P > 0.01). However, both diabetes groups had significantly higher BMI than the non-diabetes group (P < 0.01) [Table 2]. Periodontitis was not associated with differences in plasma lipid status in type 2 diabetes patients as assessed by levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, or Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol [Table 2]. No significant correlations were found between the diabetes-related systemic parameters in either of the two groups with diabetes (P > 0.01). However, these systemic parameters were higher in the diabetes group compared to the non-diabetes group (P < 0.01) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Systemic parameters (mean±SD) in diabetic and non-diabetic groups

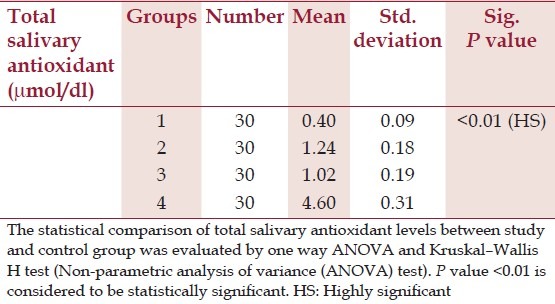

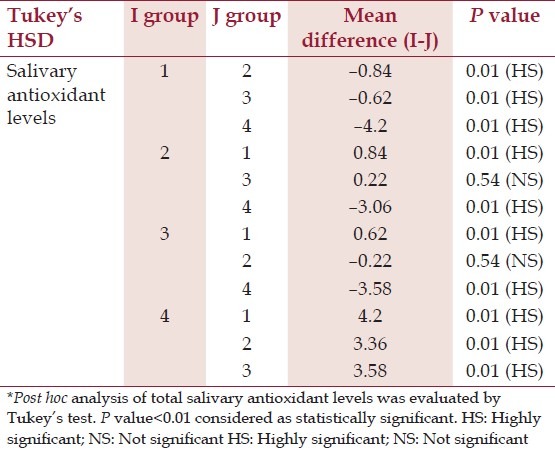

Salivary total antioxidant content in the diabetes group (1.24 ± 0.18) was statistically significantly less compared with healthy controls (4.6 ± 0.31) (P < 0.01). Statistically, there was no significant difference in the salivary total antioxidant capacity of diabetics without periodontitis and healthy individuals with periodontitis (P > 0.01). Periodontally healthy individuals revealed higher antioxidant levels (4.68 ± 0.31) in comparison to individuals with periodontitis (1.09 ± 0.19) which was statistically highly significant (P < 0.01) [Table 3]. The total antioxidant capacity was significantly lower in diabetic patients with periodontitis (0.40 ± 0.09) when compared to healthy individuals with periodontitis (1.09 ± 0.19) and diabetics without periodontal disease (1.24 ± 0.18) (P < 0.01) [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Mean values of total salivary antioxidants in the study group and control group

Table 4.

Post hoc analysis of total salivary antioxidant levels*

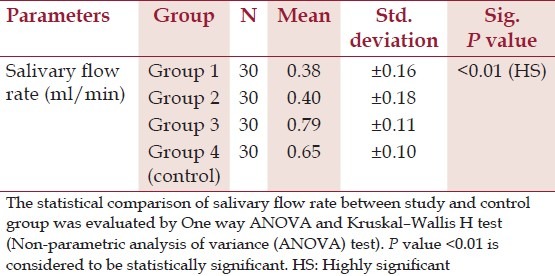

The saliva flow rates were similar in both the groups of diabetic patients (0.38 and 0.40 ml/min) and were statistically not significant. Although there were no significant difference between periodontitis subjects and controls (group 3 and 4) (P > 0.01), the salivary flow rates were significantly less in diabetic patients than the systemically healthy group (P < 0.01) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Mean values of salivary flow rate in study group and control group*

Discussion

Our data show that compared with non-diabetic subjects, type 2 diabetics are subjected to severe oxidative stress identifiable as a depletion of the total antioxidant capacity. Our data are consistent with previous studies that showed increased levels of various indices of ROS in individuals with diabetes, thus leading to depletion in total antioxidant capacity.[28–31] It has been suggested that the oxidation of lipids such as chylomicrons may play a causative role in the generation of ROS in diabetes.[32] This suggestion is consistent with the present study in which increase in plasma triglyceride and cholesterol were observed in group 2 diabetic subjects.

Many biochemical pathways, including glucose autoxidation, polyol, and prostanoid biosynthesis, and protein glycation which are associated with hyperglycemia have been implicated in the increased free radical-production in diabetic subjects.[31,33,34] Evidence of oxidative stress in diabetes has been provided either by the increased levels of degradative products of ROS,[29–33,35] deficiencies of specific antioxidants,[36] or reduction in total antioxidant capacity in diabetic patients.[36] However, relationships between the antioxidant status, glycemic control, and the risk for development of chronic complications in individuals with diabetes are not completely clear.

Our finding of depleted total antioxidant capacity in type 2 diabetes patients with periodontitis compared to type 2 diabetics without periodontitis supports this possibility and suggests that periodontitis has a negative effect on the already compromised oxidative status of type 2 diabetes patients. Oxidative stress leads to an up-regulation of pro-inflammatory pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of both periodontitis and diabetes.[22,37] One possible source of the oxidative stress identified in type 2 diabetes patients with periodontitis may be hyper-active/reactive neutrophils as both periodontitis and diabetes are associated with neutrophil priming and enhanced ROS release, correlating with both severity of periodontitis and glycemic control.[37–40,21]

It may be hypothesized that hyper-active/reactive neutrophils releasing high levels of extracellular ROS could potentially overwhelm antioxidant defenses. Further work is required to explore the impact of periodontal inflammation on insulin resistance, specifically along the oxidative stress/inflammation axis.

Antioxidants, by counteracting the harmful effects of free radicals, protect the structural and tissue integrity. Imbalances between the levels of free radicals and the levels of antioxidants were suggested to play an important role in the onset and development of several inflammatory oral diseases.[41,42]

Moore et al.[43] measured the antioxidant capacity of saliva in periodontally diseased and healthy individuals using the Trolox equivalent assay and failed to find any significant difference between the groups. In a similar study, Chapple et al.[44] studied serum and saliva samples in diseased and control groups using an enhanced chemiluminescent assay. Serum antioxidant capacity in two groups was similar; however, saliva antioxidant capacity and saliva and serum antioxidants were significantly lower in diseased patients compared with controls.

Recently, the possible association of gingivitis and periodontitis with impaired salivary antioxidant status and increased oxidative injury was investigated by Sculley and Langley – Evans.[7] These researchers reported that periodontal disease was associated with reduced salivary antioxidant status and increased oxidative damage within the oral cavity.

The results from the present study show that the total antioxidant capacity is significantly decreased in healthy subjects with periodontal disease compared with periodontally healthy controls. The alterations in total antioxidant capacity is supported by recent studies indicating that chronic periodontal disease is associated with peripheral neutrophils that are hyper-reactive with respect to the production of ROS in response to Fcγ-receptor stimulation.[45,10] Thus, periodontal disease has been suggested to be associated with reduced salivary antioxidant status and increased oxidative damage within the oral cavity.

Stimulation of saliva may increase the flow of Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF), which may result in a false increase in the concentration of antioxidants in the saliva.[44] Hence, in the present study, unstimulated whole saliva samples were used as it is preferred in determination of antioxidant defense parameters to stimulated saliva and moreover, it is claimed that the total antioxidant capacity is higher in unstimulated saliva.[46]

To reduce the potential confounding factors tight matching for gender, age, periodontal status, and exclusion of smokers were done in this study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported investigation of possible differences in total antioxidant capacity in periodontally healthy and diseased diabetic male subjects who were diagnosed for the first time (fresh cases) and were not under any medication.

The principal limitations of our study include the small sample size, the lack of serum, and gingival crevicular fluid data on antioxidants and inclusion of female subjects with menstrual cycle. However, these were beyond the scope of the present study, and evaluation of the antioxidant profile in saliva was the particular goal. Evaluation of serum and/or gingival crevicular fluid samples could be the aim of a separate study.

Conclusion

Based on the results from the present study and data available from the literature, there is increasing evidence that oxidative stress may be an important contributing factor in the pathogenesis of diabetes and periodontal disease. The co-existence of both diseases may augment the pathological effects of oxidative stress.

The data reported here highlight the need for diagnosis and treatment of periodontitis in type 2 diabetes patients to minimize the potential pathogenic effects of cumulative oxidative stress upon B-cell function and glycemic control.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.van Dyke TE. Cellular and molecular susceptibility determinants for periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2007;45:10–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh PD, Devine DA. How is the development of dental biofilms influenced by the host? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredriksson MI, Gustafsson AK, Bergström KG, Asman BE. Constitutionally hyperreactive neutrophils in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:219–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews JB, Wright HJ, Roberts A, Cooper PR, Chapple IL. Hyperactivity and reactivity of peripheral blood neutrophils in chronic periodontitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:255–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panjamurthy K, Manoharan S, Ramachandran CR. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in patients with periodontitis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2005;10:255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugano N, Kawamoto K, Numazaki H, Murai S, Ito K. Detection of mitochondrial DNA mutations in human gingival tissues. J Oral Sci. 2000;42:221–3. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.42.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sculley DV, Langley-Evans SC. Periodontal disease is associated with lower antioxidant capacity in whole saliva and evidence of increased protein oxidation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;105:167–72. doi: 10.1042/CS20030031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akalin FA, Toklu E, Renda N. Analysis of superoxide dismutase activity levels in gingiva and gingival crevicular fluid in patients with chronic periodontitis and periodontally healthy controls. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:238–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis SD, Tucci MA, Serio FG, Johnson RB. Factors for progression of periodontal diseases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:101–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapple IL, Brock G, Eftimiadi C, Matthews JB. Glutathione in gingival crevicular fluid and its relation to local antioxidant capacity in periodontal health and disease. Mol Pathol. 2002;55:367–73. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock GR, Butterworth CJ, Matthews JB, Chapple IL. Local and systemic total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis and health. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:515–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–69. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halliwell B. Reactive oxygen species in living systems: Source, biochemistry, and role in human disease. Am J Med. 1991;91:14S–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor GW. Bidirectional interrelationships between diabetes and periodontal diseases: An epidemiologic perspective. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:99–112. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HJ, Garcia RI, Janket SJ, Jones JA, Mascarenhas AK, Scott TE, et al. The association between cumulative periodontal disease and stroke history in older adults. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1744–54. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor GW, Burt BA, Becker MP, Genco RJ, Shlossman M. Glycemic control and alveolar bone loss progression in type 2 diabetes. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:30–9. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:329–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi YH, McKeown RE, Mayer-Davis EJ, Liese AD, Song KB, Merchant AT. Association between periodontitis and impaired fasting glucose and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:381–6. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes. 2003;52:1–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karima M, Kantarci A, Ohira T, Hasturk H, Jones VL, Nam BH, et al. Enhanced superoxide release and elevated protein kinase C activity in neutrophils from diabetic patients: Association with periodontitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:862–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1004583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–20. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Report of the Expert Committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unal T, Firatli E, Sivas A, Meric H, Oz H. Fructosamine as a possible monitoring parameter in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1993;64:191–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prieto P, Pineda M, Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: Specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal Biochem. 1999;269:337–41. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koracevic D, Koracevic G, Djordjevic V, Andrejevic S, Cosic V. Method for the measurement of antioxidant activity in human fluids. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:356–61. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.5.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santini SA, Marra G, Giardina B, Cotroneo P, Mordente A, Martorana GE, et al. Defective plasma antioxidant defenses and enhanced susceptibility to lipid peroxidation in uncomplicated IDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46:1853–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberley LW. Free radicals and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;5:113–24. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baynes JW, Thorpe SR. Role of oxidative stress in diabetic complications: A new perspective on an old paradigm. Diabetes. 1999;48:1–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G. Oxidative stress and diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:257–67. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staprans I, Rapp JH, Pan XM, Feingold KR. The effect of oxidized lipids in the diet on serum lipoprotein peroxides in control and diabetic rats. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:638–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI116632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paolisso G, Giugliano D. Oxidative stress and insulin action: Is there a relationship? Diabetologia. 1996;39:357–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00418354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Low PA, Nickander KK, Tritschler HJ. The roles of oxidative stress and antioxidant treatment in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 1997;46:S38–42. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdella N, al Awadi F, Salman A, Armstrong D. Thiobarbituric acid test as a measure of lipid peroxidation in Arab patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Res. 1990;15:173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell SR, Thomason H, Sandler D, Leguen C, Baxter MA, Thorpe GH, et al. Antioxidant status in patients with uncomplicated insulin-dependent and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest. 1997;27:484–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.1390687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapple IL, Brock GR, Milward MR, Ling N, Matthews JB. Compromised GCF total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis: Cause or effect? J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:103–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fredriksson MI, Gustafsson AK, Bergström KG, Asman BE. Constitutionally hyperreactive neutrophils in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:219–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapple IL, Matthews JB. The role of reactive oxygen and antioxidant species in periodontal tissue destruction. Periodontol 2000. 2007;43:160–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews JB, Wright HJ, Roberts A, Cooper PR, Chapple IL. Hyperactivity and reactivity of peripheral blood neutrophils in chronic periodontitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:255–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chapple IL. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:287–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battino M, Bullon P, Wilson M, Newman H. Oxidative injury and inflammatory periodontal diseases: The challenge of anti-oxidants to free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1999;10:458–76. doi: 10.1177/10454411990100040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore S, Calder KA, Miller NJ, Rice-Evans CA. Antioxidant activity of saliva and periodontal disease. Free Radic Res. 1994;21:417–25. doi: 10.3109/10715769409056594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapple IL, Mason GI, Garner I, Matthews JB, Thorpe GH, Maxwell SR, et al. Enhanced chemiluminescent assay for measuring the total antioxidant capacity of serum, saliva and crevicular fluid. Ann Clin Biochem. 1997;34:412–21. doi: 10.1177/000456329703400413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fredriksson M, Gustafsson A, Asman B, Bergström K. Periodontitis increases chemiluminescence of the peripheral neutrophils independently of priming by the preparation method. Oral Dis. 1999;5:229–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pereslegina IA. The activity of antioxidant enzymes in the saliva of normal children. Lab Delo. 1989;11:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emrich LJ, Shlossman M, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1991;62:123–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]