Abstract

Background

The coordination of growth within a tissue layer is of critical importance for tissue morphogenesis. For example, cells within the epidermis undergo stereotypic cell divisions that are oriented along the plane of the layer (planar growth), thereby propagating the layered epidermal structure. Little is known about the developmental control that regulates such planar growth in plants. Recent evidence suggested that the Arabidopsis AGC VIII protein kinase UNICORN (UCN) maintains planar growth by suppressing the formation of ectopic multicellular protrusions in several floral tissues including integuments. In the current model UCN controls this process during integument development by directly interacting with the ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE (ATS) protein, a member of the KANADI (KAN) family of transcription factors, thereby repressing its activity. Here we report on the further characterization of the UCN mechanism.

Results

Phenotypic analysis of flowers of ucn-1 plants impaired in floral homeotic gene activity revealed that any of the four floral whorls could produce organs carrying ucn-1 protrusions. The ectopic outgrowths of ucn integuments did not accumulate detectable signals of the auxin and cytokinin reporters DR5rev::GFP and ARR5::GUS, respectively. Furthermore, wild-type and ucn-1 seedlings showed similarly strong callus formation upon in vitro culture on callus-inducing medium. We also show that ovules of ucn-1 plants carrying the dominant ats allele sk21-D exhibited more pronounced protrusion formation. Finally ovules of ucn-1 ett-1 double mutants and ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 triple mutants displayed an additive phenotype.

Conclusions

These data deepen the molecular insight into the UCN-mediated control of planar growth during integument development. The presented evidence indicates that UCN downstream signaling does not involve the control of auxin or cytokinin homeostasis. The results also reveal that UCN interacts with ATS independently of an ATS/ETT complex required for integument initiation and they further emphasize the necessity to balance UCN and ATS proteins during maintenance of planar growth in integuments.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Auxin, ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE, AGC protein kinase, AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 4, Cell division, Cytokinin, ETTIN, Growth regulation, KANADI, Planar growth, Ovule, Signal transduction, UNICORN

Background

In plant tissue morphogenesis the control of cell division patterns is crucial for the establishment and propagation of tissue layers. Spatially restricted asymmetric cell divisions frequently generate new cell layers. Subsequently, symmetric cell divisions maintain a cell layer, often by aligning the division planes along the plane of the layer (planar growth). The regulation of asymmetric cell divisions is under intense scrutiny [1-5]. By contrast, the developmental control of planar growth is largely unknown [6].

There is evidence for a link between the control of adaxial-abaxial polarity and the laminar growth of the leaf blade. Leaves are lateral determinate organs and are characterized by a distinct adaxial-abaxial or dorsal-ventral polarity across the whole multi-layered organ. Outgrowth of the developing leaf lamina is believed to require stimulation of cells located at the adaxial-abaxial boundary [7]. The control of adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity relies on the antagonistic interactions between Class III HD-ZIP and KANADI (KAN) transcription factors [8,9]. Class III HD-ZIP genes promote adaxial identity [10-13] and KAN genes, in conjunction with auxin response factor genes ETTIN (ETT) and ARF4, direct abaxial cell fate and lamina outgrowth in leaves [10,14-16]. Interestingly, defects in the control of adaxial identity can result in localized ectopic blade-like outgrowths on adaxial surface of affected leaves [13,17]. Similarly, it has been observed that misregulation of abaxial leaf polarity can lead to ectopic blade-like outgrowths on the abaxial side of leaves and cotyledons [18,19].

Evidence for a connection between the regulation of adaxial-abaxial polarity and planar growth also comes from studies using Arabidopsis integuments as model system [20,21]. Integuments are lateral determinate tissues of ovules and the progenitors of the seed coat. Arabidopsis ovules develop an inner and outer integument of entirely epidermal origin [22,23]. Upon initiation they form laminar extensions of distinct adaxial-abaxial polarity each consisting of two cell layers of anticlinally dividing cells. The outer integument will grow asymmetrically and eventually envelop the inner integument and the developing embryo sac.

Recently it was discovered that maintenance of planar growth of integuments is under control of UNICORN (UCN) [20,21]. UCN encodes a functional protein kinase that belongs to the AGC2 subclass of the plant-specific AGC VIII family [24-27]. Integuments of recessive ucn mutants exhibit local disorganized growth resulting in the formation of one to several multicellular protrusions containing cells with at least partial integument identity. Similar protrusions are also present on stamens and petals. At the cellular level, the earliest detectable defects are local periclinal or oblique cell divisions in individual cell layers. They are clearly distinct from the typical anticlinal cell divisions that maintain planar growth of integuments. In addition, ucn proembryos show altered cell division planes and double mutants carrying null alleles of UCN and its closest homolog UNICORN-LIKE (UCNL) are embryo lethal. These observations indicated that UCN suppresses ectopic growth by influencing division planes in symmetrically dividing cells.

UCN maintains planar growth during integument outgrowth by interacting with ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE (ATS) [21]. ATS is a KAN gene required for several processes of integument development including, integument boundary formation, inner integument outgrowth and the control of adaxial-abaxial polarity [28-31]. In addition, the ATS protein appears to form a functional complex with the auxin response factor ETTIN (ETT) [32] to control early integument development [33]. Protrusion formation in integuments of ucn ats double mutants is strongly diminished indicating that UCN represses ATS[21]. This negative regulation is likely to occur through physical interaction of the two proteins as ATS transcript levels are unaltered in ucn mutants and recombinant UCN protein is able to phosphorylate ATS in in vitro kinase assays. Moreover, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis further supports direct physical interaction between UCN and ATS [21]. Thus, by inhibiting ATS UCN appears to prevent misregulation of transcriptional programs that control planar growth in integuments.

Here we further characterize UCN-mediated maintenance of planar growth during integument development. We provide evidence that UCN functions in an organ-specific manner and that UCN does not influence auxin and cytokinin homeostasis. Our data further suggest that UCN and ATS protein levels must be balanced and that repression of ATS by UCN does not involve either ETT or the ATS/ETT complex.

Results and discussion

UCN functions in an organ- not a whorl-specific manner in floral organogenesis

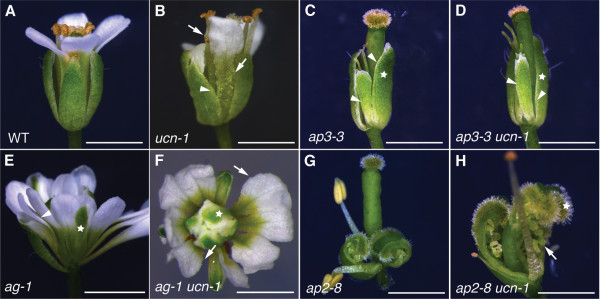

Flowers carry four different types of floral organs arranged in whorls. In Arabidopsis, sepals occupy whorl 1, petals whorl 2, stamens whorl 3 and carpels including the ovules whorl 4 [34]. According to the ABC model floral organ identity is specified at the whorl level by a set of floral homeotic genes, encoding mostly MADS-domain transcription factors, that act in a combinatorial fashion [35-37]. Interestingly, ucn mutants show protrusions in petals, stamen and ovules (Figure 1B, Figure 2B) [21], however, we never observed protrusions on sepals or carpels. This observation raised the question whether UCN acts in an organ- or whorl-specific manner.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic analysis of ap3 ucn, ag ucn and ap2 ucn flowers. Light micrographs of stage 14 flowers. Arrows indicate protrusions, arrowheads indicate absence of protrusions. (A) Wild-type (Ler). (B) ucn-1. Note the presence of protrusions on petals and stamens but their absence on sepals. (C) ap3-3. One first-whorl sepal was removed to reveal the inner second-whorl sepal. The star indicates a first-whorl sepal. (D) ap3-3 ucn-1 double mutant. Similar setup as in (C). Note the absence of protrusions on the second-whorl sepal. Serrations at the tip of the second-whorl sepal regularly occur in ap3-3 single mutants. (E) ag-1 flower. Star indicates a fourth-whorl sepal. (F) ag-1 ucn-1 double mutant. Protrusions are found on second- and third-whorl petals. (G) ap2-8. First-whorl unfused carpels with ovules are visible. (H) ap2-8 ucn-1. The first-whorl ovules carry protrusions. Scale bars: 0.5 mm.

Figure 2.

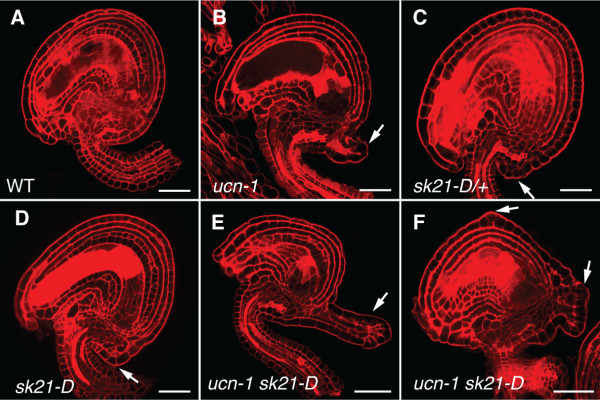

Ovules of ucn-1 sk21-D mutants show enhanced protrusion formation. Confocal micrographs of early stage 4 ovules stained with pseudo-Schiff propidium iodide (mPS PI) are shown. Arrows indicate protrusions. (A) Wild-type ovule (Ler). (B) ucn-1 ovule. Note the presence of a protrusion. (C) sk21-D/+ ovule. A small protrusion is indicated. (D) sk21-D ovule. (E, F) ucn-1 sk21-D ovules. (E) Note the prominently enlarged protrusion (compare with B, D). (F) Multiple protrusions are detectable. Scale bars: 20 μm.

To address this issue we generated a set of double mutants between ucn-1 and several floral homeotic mutants (Figure 1). Flowers of apetala3 (ap3) mutants carry sepals in whorl 2 and carpels in whorl 3 [38]. The second whorl sepals of ucn-1 ap3-3 flowers did not show ucn-like protrusions (Figure 1D), although the second-whorl petals of ucn-1 mutants do, providing first evidence that UCN acts in an organ and not a whorl-specific manner. To test this assumption further we analyzed two additional combinations. Plants with a defect in AGAMOUS (AG) exhibit petals in the third whorl and an additional flower in the fourth whorl [38]. Third-whorl petals of ucn-1 ag-1 still showed protrusions (Figure 1F). In apetala2 (ap2) mutants unfused carpels with ovules and stamens develop in the first whorl and second whorl, respectively [38-40]. Flowers of ucn-1 ap2-8 double mutants were characterized by first-whorl carpels devoid of protrusions but that included ucn-like ovules (Figure 1H). Thus, in particular the phenotypes of ucn-1 ap3-3 and ucn-1 ap2-8 flowers suggest that UCN acts in an organ-specific rather than whorl-specific manner in floral organogenesis.

Outgrowths in ucn-1 integuments develop autonomously of auxin and cytokinin

The maintenance of plant tissue morphogenesis and the prevention of aberrant growth and tumor formation is under hormonal and genetic control [41-43]. For example, callus formation can be induced at non-wounding sites in explants by in vitro auxin and cytokinin treatment [44,45] resulting in masses of partially dedifferentiated cells that resemble root meristem tips [46-48]. Furthermore, defects in PROPORZ1 (PRZ1), encoding a putative component of a chromatin-remodeling complex, result in callus formation upon addition of auxin or cytokinin [49]. In addition, ectopic expression of AINTEGUMENTA (ANT), encoding an AP2-class transcription factor involved in the control of cell division and organ initiation [50-57], results in unorganized cell proliferation in wounded or detached ends of fully differentiated leaves [58]. ANT acts downstream of auxin and regulates meristematic competence during organogenesis [58,59].

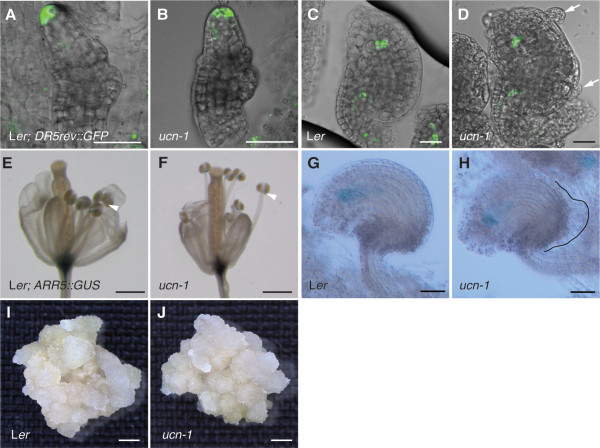

To explore the relationship between UCN and auxin as well as cytokinin we tested whether the integument protrusions of ucn-1 expressed the well-characterized reporters DR5rev::GFP or ARR5::GUS that act as proxies for the presence of auxin and cytokinin, respectively [60,61]. We observed DR5rev::GFP signal distribution as reported previously in developing ovules, such as the tip of the ovule primordium or the micropylar end of the young embryo sac [61,62]. Interestingly, however, no signal could be seen in variably advanced protrusions of ucn-1 integuments (Figure 3A-D). ARR5::GUS expression could be observed in the tip of filaments as noted earlier [63]. During ovule development we could also detect a signal in the developing embryo sac. The latter signal is in accordance with the expression pattern of the IPT1::GUS reporter, using the promoter of a cytokinin biosynthesis enzyme [64,65], and the synthetic cytokinin reporter TCSpro::GFP[65,66]. However, we did not observe ARR5::GUS signal in developing protrusions of ucn-1 integuments (Figure 3E-H). These results suggest that ucn-1 integument protrusions do not accumulate auxin or cytokinin, at least not to a level or in a fashion detectable by these two reporters.

Figure 3.

Hormone-induced callus formation is not affected in ucn-1 seedlings and ucn-1 protrusions do not accumulate detectable DR5rev::GFP and ARR5::GUS reporter signals. (A-D) Confocal micrographs of live wild-type (Ler) and ucn-1 plants carrying the DR5rev::GFP reporter. Overlays of GFP and bright-field channels. No difference in signal detected between wild-type and ucn-1. (A, B) Stage 2-III ovules. (C, D) Stage 3-III ovules. Note the absence of detectable signal in the ucn-1 protrusions (arrows). (E-H) Plants carrying the ARR5::GUS reporter. No difference in signal detected between wild-type and ucn-1. (E, F) Light micrographs of fixed stage 14 flowers (4 h incubation in GUS staining solution). Arrowheads indicate signal at the junction between filament and anther. (G, H) Differential interference contrast micrographs of fixed stage 3-IV ovules (16 h incubation in GUS staining solution). Note the absence of signal in the ucn-1 protrusion (outlined). (I) Light micrograph of a 30-days-old callus grown from germinated wild-type (Ler) seedling grown on callus induction medium (CIM). (J) Light micrograph of a 30-days-old callus grown from germinated ucn-1 seedling grown on CIM. Callus is of comparable size than the one in (I). Scale bars: (A-D): 20 μm, (G, H) 30 μm, (E, F, I, J) 0.5 mm.

To assess further the relationship between UCN and auxin as well as cytokinin we tested whether UCN influences callus formation in seedlings treated with exogenous auxin and cytokinin. However, when comparing wild-type and ucn-1 seedlings grown on callus inducing medium (CIM) we detected no difference in size or number of formed calli (Figure 3I, J) (n = 25). Thus, it appears that UCN does not affect hormone-induced callus formation in this assay.

The reporter-based experiments described above need to be interpreted with caution. Still, the results are also in accordance with previous genetic data. For example, the additive ovule phenotype of ucn bel1 double mutants [21] further supports the notion that ucn integument protrusions develop autonomously of auxin. BEL1 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor required for chalaza development [20,67-69]. Plants lacking BEL1 activity develop ovules carrying large protrusions emanating from the chalaza. Interestingly, young protrusions of bel1 ovules show ectopic expression of a PIN1::PIN1:GFP reporter [65], used to assess the presence of the polar auxin transport facilitator PIN1 [70,71]. Furthermore, bel1 mutants treated with the polar auxin transport inhibitor N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) failed to form protrusions. These results indicate that auxin contributes to the formation of bel1 outgrowths [65]. If auxin would play a major role in the induction of outgrowth formation in ucn-1 integuments one might expect enlarged protrusion formation in ucn bel1 double mutants. However, this is not the case, as ucn bel1 double mutants did not show a noticeable increase in protrusion size [21]. In addition, protrusion formation still occurs on petals and stamen in ucn ant double mutants [21].

Available evidence suggests that cytokinin may be of little importance for the control of integument outgrowth. Signaling mediated by the three cytokinin receptor genes CRE1, AHK2, and AHK3[72] appears to be critical for ovule primordium outgrowth [65] and embryo sac development [65,73]. However, these genes appear to play a minor role if any during integument outgrowth as either no defects in integument development [73] or only a frequency of 10 percent of finger-like ovules lacking integuments [65] were reported in strong cre1 ahk2 ahk3 triple mutants. These affected ovules may have still suffered from defects occurring during prior primordium outgrowth. The absence of detectable ARR5::GUS expression in ucn-1 protrusions, consisting of at least partially differentiated integument cells, may thus reflect the minor role of cytokinin in integument outgrowth.

Taken together the available evidence suggests that processes functioning downstream of UCN growth suppression do not involve the regulation of auxin and cytokinin homeostasis.

Relative levels of UCN and ATS are critical for planar growth of integuments

The current model states that UCN maintains planar growth in integuments by directly repressing the activity of the ATS protein implying that the balance between UCN and ATS proteins may be crucial in this process. Previously we could show that an about 45-fold increase of ATS transcript levels within its normal spatial expression domain in the activation tagging mutant sk21-D[74] is accompanied by ucn-like protrusion formation in integuments [21]. This result supports the genetic model that UCN is a negative regulator of ATS. One interpretation of the sk21-D integument phenotype includes the assumption that elevated ATS transcript levels lead to higher than normal amounts of ATS protein, which may titrate out available UCN. If this notion is correct one might expect that upon reduction of UCN function even more exaggerated protrusion formation should take place in sk21-D plants.

To test this notion we performed a genetic gene dosage assay (Figure 2, Table 1). Ovules of ucn-1/+ plants do not show protrusions [21]. Analysis of ovules of sk21-D/+ heterozygous plants revealed less prominent protrusion formation than in ovules of sk21-D homozygous plants (Figure 2C, D). Furthermore, we generated ucn-1 plants that were either heterozygous or homozygous for sk21-D. Indeed ovules of these mutants showed an increase in protrusion formation, both in terms of protrusion size (Figure 2E) and in number of protrusions formed (Figure 2F, Table 1). Strongest effects were seen in ucn-1 sk21-D double mutants. A dosage effect was discernable as ucn-1 plants heterozygous for sk21-D showed an intermediate phenotype compared to ucn-1 or ucn-1 homozygous for sk21-D (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quantification of protrusion number on ovules of wild-type, ucn-1, sk21-D, and ucn-1 sk21-D mutants

| Genotype | No. of ovules analyzed | No. of ovules with only one protrusion | No. of ovules with >1 protrusions | % of ovules with protrusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT |

200 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

ucn-1 |

200 |

96 |

89 |

92.5 |

|

sk21-D/+ |

200 |

11 |

0 |

5.5 |

|

sk21-D |

200 |

87 |

2 |

44.5 |

|

ucn-1 sk21-D/+ |

200 |

93 |

95 |

94 |

| ucn-1 sk21-D | 200 | 34 | 158 | 96 |

Taken together these data support the model that elevated transcript levels of ATS can ultimately lead to out-titration of functional UCN. In addition, they provide further genetic evidence that it is indeed critical to maintain a proper balance between UCN and ATS protein levels in the regulation of planar integument growth.

UCN acts independently of ETT and ARF4 during integument development

Genetic studies indicated that AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR (ARF) gene ETTIN (ETT) and its closest homolog ARF4 are required for the control of adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity in conjunction with KAN1 and KAN2[16]. Furthermore, the ETT and ATS proteins may physically interact to form a functional complex required for integument development and polarity [33]. Our previous data suggested that UCN maintains planar growth of integuments by negatively regulating the polarity factor ATS through a physical interaction between the two proteins [21]. If interaction between ATS and ETT proteins is crucial for the formation of a functional complex then impairing either protein should result in similar absence of function. As a consequence ats and ett should show a similar genetic behavior with respect to ucn.

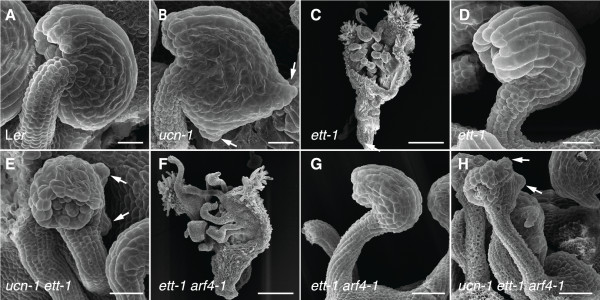

To test this hypothesis we generated ucn-1 ett-1 double and ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 triple mutants and analyzed their ovule phenotypes (Figure 4). In agreement with a repressive role of UCN on ATS activity ats is epistatic to ucn-1 in ucn-1 ats-3 double mutants [21]. Ovules of ett-1 mutants displayed an ats-like phenotype (Figure 4D) confirming earlier results [33]. Surprisingly, however, ovules of ucn-1 ett-1 double mutants (Figure 4D) or ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 triple mutants (Figure 4H) exhibited an additive phenotype. These results suggest that UCN and ETT/ARF4 function in different pathways. They further indicate that UCN does not participate in auxin-related aspects of integument development that involve these two auxin response factors.

Figure 4.

Ovules of ucn-1 ett-1 and ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 mutants show additive phenotypes. Scanning electron micrographs of early stage 4 ovules are depicted with the exception of (C, F) which show gynoecia of stage 14 flowers. (A) Wild-type ovule. (B) ucn-1 ovule. Arrows highlight protrusions. (C) Typical gynoecium of an ett-1 flower. (D) ett-1 ovule. (E) Additive phenotype of a ucn-1 ett-1 double mutant ovule. Note the protrusions (arrows). (F) Typical gynoecium of an ett-1 arf4-1 flower. (G) ett-1 arf4-1 ovule. Not noticeably different from an ett-1 ovule (compare with D). (H) Additive phenotype of a ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 triple mutant ovule. Not noticeably different from a ucn-1 ett-1 double mutant ovule (compare with E). Arrows mark protrusions. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Interestingly, the additive ovule phenotype of ucn-1 ett-1 double mutants and ucn-1 ett-1 arf4-1 triple mutants seems not in accordance with the notion of a functional ATS/ETT complex. How can this apparent discrepancy be resolved? At least two models are conceivable. In one scenario the ATS/ETT complex is required throughout integument development and UCN inactivates ATS that is not in a complex with ETT. Alternatively, the ATS/ETT complex is transient and only active during early integument development. Sometime after integument initiation the ATS/ETT complex ceases to be required and dissociates. UCN then interacts with now available free ATS and represses its activity. We favor the latter model as the ATS-dependent protrusions in integuments of ucn-1 or sk21-D mutants first appear once integuments are initiated and continue to outgrow [21].

Both models detailed above imply that ATS protein that is not bound to ETT interferes with the transcriptional programs regulating planar integument growth and must be repressed. Thus, the new genetic data presented above are in agreement with and at the same time refine our current view on the UCN-mediated control of planar integument growth.

Conclusions

Here we provide genetic data that UCN acts in an organ-specific manner during floral development. Furthermore, the repression of ectopic growth by UCN-mediated signaling does not appear to involve a control of auxin or cytokinin homeostasis. UCN-dependent growth suppression is mediated through a repression of ATS and requires a critical balance of both proteins. This repression is independent of a likely earlier-acting ATS/ETT protein complex involved in integument initiation. The presented evidence deepens our understanding of UCN-mediated suppression of ectopic growth. It furthers the link between the control of adaxial-abaxial polarity and planar growth and contributes to a solid experimental and conceptual foundation for further exploration of planar growth control during integument development.

Methods

Plant work

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. var. Columbia (Col-0) and var. Landsberg (erecta mutant) (Ler) were used as wild-type strains. Plants were grown essentially as described previously [20]. The following mutants were used: ag-1[38,75]; ap2-8[35], ap3-3[76], arf4-1[16,77,78], ett-1[16,79], sk21-D[74], ucn-1[20,21]. In double-mutant studies respective double mutants were identified based on their phenotypes segregating in a Mendelian fashion. The ucn-1 sk21-D/+ or ucn-1 sk21-D/sk21-D plants were genotyped using primers sk21-D (GT)_F :GAGAATTAGTACAATGTAATG, sk21-D (GT)_R :GTGATTTAACCCTTCTCAAGTGC and pSKI (GT)_F: CCACCCACGAGGAACATCGTG.

In vitro culture and hormone treatment

Seedlings were grown in a growth room under constant light conditions at 23°C. For induction of callus freshly germinated seedlings were grown on MS plates for 6 days. Seedlings were then transferred onto MS plates supplemented with 3 μg/ml each of the auxin 1-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) (Sigma) and the cytokinin kinetin (Sigma) (callus induction medium, CIM).

Microscopy and art work

Preparation and analysis of samples for light microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and histochemical localization of β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity in whole-mount tissue was done essentially as described [20,80]. Ovule staining with pseudo-Schiff propidium iodide (mPS-PI) was done as described [81]. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed with an Olympus FV1000 setup and FluoView software (Olympus Europa GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) as described previously [21]. Images were adjusted for color and contrast using Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) software.

Authors’ contributions

BE conceived of the study, participated in the design, and carried out experiments. KS conceived of the study, participated in the design and coordination and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Balaji Enugutti, Email: balaji.enugutti@imba.oeaw.ac.at.

Kay Schneitz, Email: schneitz@wzw.tum.de.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Friml and Alex Christmann for providing the DR5rev::GFP and ARR5::GUS lines, respectively. We also thank J. Lohmann for sending the ett-1 and arf4-1 mutants and members of the Schneitz lab for fruitful discussions. This work was funded by grants SCHN 723/3-1 and SCHN 723/3-2 (KS) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

References

- Abrash EB, Bergmann DC. Asymmetric cell divisions: a view from plant development. Dev Cell. 2009;16:783–796. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ramirez A, Diaz-Trivino S, Blilou I, Grieneisen VA, Sozzani R, Zamioudis C, Miskolczi P, Nieuwland J, Benjamins R, Dhonukshe P, Caballero-Perez J, Horvath B, Long Y, Mahonen AP, Zhang H, Xu J, Murray JA, Benfey PN, Bako L, Maree AF, Scheres B. A bistable circuit involving SCARECROW-RETINOBLASTOMA integrates cues to inform asymmetric stem cell division. Cell. 2012;150:1002–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet I, Beeckman T. Asymmetric cell division in land plants and algae: the driving force for differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:177–188. doi: 10.1038/nrm3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Weits DA, Cruz-Ramirez A, Deinum EE, Tindemans SH, Kakar K, Prasad K, Mahonen AP, Ambrose C, Sasabe M, Wachsmann G, Luijten M, Bennett T, Machida Y, Heidstra R, Wasteneys G, Mulder BM, Scheres B. A PLETHORA-auxin transcription module controls cell division plane rotation through MAP65 and CLASP. Cell. 2012;149:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petricka JJ, Van Norman JM, Benfey PN. Symmetry breaking in plants: molecular mechanisms regulating asymmetric cell divisions in Arabidopsis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000497. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen CG, Humphries JA, Smith LG. Determination of symmetric and asymmetric division planes in plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2011;62:387–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites R, Hudson A. phantastica: a gene required for dorsoventrality of leaves in Antirrhinum majus. Development. 1995;121:2143–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Husbands AY, Chitwood DH, Plavskin Y, Timmermans MC. Signals and prepatterns: new insights into organ polarity in plants. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1986–1997. doi: 10.1101/gad.1819909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakonyi D, Moschopoulos A, Byrne ME. Perspectives on leaf dorsoventral polarity. J Plant Res. 2010;123:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10265-010-0336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JF, Floyd SK, Alvarez J, Eshed Y, Hawker NP, Izhaki A, Baum SF, Bowman JL. Radial patterning of Arabidopsis shoots by class III HD-ZIP and KANADI genes. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell JR, Emery J, Eshed Y, Bao N, Bowman J, Barton MK. Role of PHABULOSA and PHAVOLUTA in determining radial patterning in shoots. Nature. 2001;411:709–713. doi: 10.1038/35079635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell JR, Barton MK. Leaf polarity and meristem formation in Arabidopsis. Development. 1998;125:2935–2942. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge MJ, Otsuga D, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Drews GN, Clark SE. Class III homeodomain-leucine zipper gene family members have overlapping, antagonistic, and distinct roles in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:61–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Baum SF, Perea JV, Bowman J. Establishment of polarity in lateral organs of plants. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00392-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter RA, Bollman K, Taylor RA, Bomblies K, Poethig RS. KANADI regulates organ polarity in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;411:706–709. doi: 10.1038/35079629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekker I, Alvarez JP, Eshed Y. Auxin response factors mediate Arabidopsis organ asymmetry via modulation of KANADI activity. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2899–2910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinon V, Etchells JP, Rossignol P, Collier SA, Arroyo JM, Martienssen RA, Byrne ME. Three PIGGYBACK genes that specifically influence leaf patterning encode ribosomal proteins. Development. 2008;135:1315–1324. doi: 10.1242/dev.016469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Izhaki A, Baum SF, Floyd SK, Bowman JL. Asymmetric leaf development and blade expansion in Arabidopsis are mediated by KANADI and YABBY activities. Development. 2004;131:2997–3006. doi: 10.1242/dev.01186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izhaki A, Bowman JL. KANADI and class III HD-Zip gene families regulate embryo patterning and modulate auxin flow during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:495–508. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneitz K, Hülskamp M, Kopczak SD, Pruitt RE. Dissection of sexual organ ontogenesis: a genetic analysis of ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1997;124:1367–1376. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enugutti B, Kirchhelle C, Oelschner M, Torres Ruiz RA, Schliebner I, Leister D, Schneitz K. Regulation of planar growth by the Arabidopsis AGC protein kinase UNICORN. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15060–15065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205089109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenik PD, Irish VF. Regulation of cell proliferation patterns by homeotic genes during Arabidopsis floral development. Development. 2000;127:1267–1276. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneitz K, Hülskamp M, Pruitt RE. Wild-type ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana: a light microscope study of cleared whole-mount tissue. Plant J. 1995;7:731–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07050731.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bögre L, Ökrész L, Henriques R, Anthony RG. Growth signalling pathways in Arabidopsis and the AGC protein kinases. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:424–431. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván-Ampudia CS, Offringa R. Plant evolution: AGC kinases tell the auxin tale. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt H, Garcia AV, Oelmuller R. AGC kinases in plant development and defense. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:1030–1033. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.7.15580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McCormick S. AGCVIII kinases: at the crossroads of cellular signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léon-Kloosterziel KM, Keijzer CJ, Koornneef M. A seed shape mutant of Arabidopsis that is affected in integument development. Plant Cell. 1994;6:385–392. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian S, Schneitz K. NOZZLE links proximal-distal and adaxial-abaxial pattern formation during ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2002;129:4291–4300. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAbee JM, Hill TA, Skinner DJ, Izhaki A, Hauser BA, Meister RJ, Venugopala Reddy G, Meyerowitz EM, Bowman JL, Gasser CS. ABERRANT TESTA SHAPE encodes a KANADI family member, linking polarity determination to separation and growth of Arabidopsis ovule integuments. Plant J. 2006;46:522–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DR, Skinner DJ, Gasser CS. Roles of polarity determinants in ovule development. Plant J. 2009;57:1054–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A, Nemhauser JL, McColl A, Roe JL, Feldmann KA, Zambryski PC. ETTIN patterns the Arabidopsis floral meristem and reproductive organs. Development. 1997;124:4481–4491. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DR, Arreola A, Gallagher TL, Gasser CS. ETTIN (ARF3) physically interacts with KANADI proteins to form a functional complex essential for integument development and polarity determination in Arabidopsis. Development. 2012;139:1105–1109. doi: 10.1242/dev.067918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth DR, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1990;2:755–767. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.8.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Genetic interactions among floral homeotic genes of Arabidopsis. Development. 1991;112:1–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen ES, Meyerowitz EM. The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature. 1991;353:31–37. doi: 10.1038/353031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann JU, Weigel D. Building beauty: the genetic control of floral patterning. Dev Cell. 2002;2:135–142. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman JL, Smyth DR, Meyerowitz EM. Genes directing flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1989;1:37–52. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaki MK, Okada K, Nishino E, Shimura Y. Isolation and characterization of novel mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana defective in flower development. Development. 1988;104:195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst L, Klenz JE, Martinez-Zapater J, Haughn GW. AP2 gene determines the identity of perianth organs in flowers of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 1989;1:1195–1208. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.12.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodueva IE, Frolova NV, Lutova LA. Plant tumorigenesis: different ways for shifting systemic control of plant cell division and differentiation. Transgen Plant J. 2007;1:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Doonan JH, Sablowski R. Walls around tumours - why plants do not develop cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:794–802. doi: 10.1038/nrc2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enugutti B, Kirchhelle C, Schneitz K. On the genetic control of planar growth during tissue morphogenesis in plants. Protoplasma. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skoog F, Miller CO. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;54:118–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens D, Van Montagu M, Lijsebettens M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5536–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta R, Laurens L, Boucheron-Dubuisson E, Guivarc'h A, Carnero E, Giraudat-Pautot V, Rech P, Chriqui D. Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J. 2009;57:626–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Lall S, Howell SH. Developmental steps in acquiring competence for shoot development in Arabidopsis tissue culture. Planta. 2007;226:1183–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Jiao Y, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;18:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieberer T, Hauser M-T, Seifert GJ, Luschnig C. PROPORZ1, a putative Arabidopsis transcriptional adaptor protein, mediates auxin and cytokinin signals in the control of cell proliferation. Curr Biol. 2003;13:837–842. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott RC, Betzner AS, Huttner E, Oakes MP, Tucker WQ, Gerentes D, Perez P, Smyth DR. AINTEGUMENTA, an APETALA2-like gene of Arabidopsis with pleiotropic roles in ovule development and floral organ growth. Plant Cell. 1996;8:155–168. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucher KM, Chow H, Reiser L, Fischer RL. The AINTEGUMENTA gene of Arabidopsis required for ovule and female gametophyte development is related to the floral homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell. 1996;8:137–153. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek BA, Prost V, Macias A. AINTEGUMENTA promotes petal identity and acts as a negative regulator of AGAMOUS. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1357–1366. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek BA. AINTEGUMENTA utilizes a mode of DNA recognition distinct from that used by proteins containing a single AP2 domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1859–1868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Franks RG, Klink VP. Regulation of gynoecium marginal tissue formation by LEUNIG and AINTEGUMENTA. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1879–1892. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Barton MK. Initiation of axillary and floral meristems in Arabidopsis. Dev Biol. 2000;218:341–353. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nole-Wilson S, Krizek BA. DNA binding properties of the Arabidopsis floral development protein AINTEGUMENTA. Nucleic Acids Resesarch. 2000;28:4076–4082. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneitz K, Baker SC, Gasser CS, Redweik A. Pattern formation and growth during floral organogenesis: HUELLENLOS and AINTEGUMENTA are required for the formation of the proximal region of the ovule primordium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1998;125:2555–2563. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.14.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami Y, Fischer RL. Plant organ size control: AINTEGUMENTA regulates growth and cell numbers during organogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:942–947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Xie Q, Chua NH. The Arabidopsis auxin-inducible gene ARGOS controls lateral organ size. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1951–1961. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I, Sheen J. Two-component circuitry in Arabidopsis cytokinin signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413:383–389. doi: 10.1038/35096500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Vieten A, Sauer M, Weijers D, Schwarz H, Hamann T, Offringa R, Jürgens G. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2003;426:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnussat GC, Alandete-Saez M, Bowman JL, Sundaresan V. Auxin-dependent patterning and gamete specification in the Arabidopsis female gametophyte. Science. 2009;324:1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.1167324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliji S, Lacatus G, Sunter G. The interaction between geminivirus pathogenicity proteins and adenosine kinase leads to increased expression of primary cytokinin-responsive genes. Virology. 2010;402:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K, Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kakimoto T. Expression of cytokinin biosynthetic isopentenyltransferase genes in Arabidopsis: tissue specificity and regulation by auxin, cytokinin, and nitrate. Plant J. 2004;37:128–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencivenga S, Simonini S, Benkova E, Colombo L. The transcription factors BEL1 and SPL are required for cytokinin and auxin signaling during ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2886–2897. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller B, Sheen J. Cytokinin and auxin interaction in root stem-cell specification during early embryogenesis. Nature. 2008;453:1094–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature06943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Beers K, Pruitt RE, Gasser CS. Ovule development in wild-type Arabidopsis and two female-sterile mutants. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1237–1249. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrusan Z, Reiser L, Feldmann KA, Fischer RL, Haughn GW. Homeotic transformation of ovules into carpel-like structures in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1994;6:333–349. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser L, Modrusan Z, Margossian L, Samach A, Ohad N, Haughn GW, Fischer RL. The BELL1 gene encodes a homeodomain protein involved in pattern formation in the Arabidopsis ovule primordium. Cell. 1995;83:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gälweiler L, Guan C, Müller A, Wisman E, Mendgen K, Yephremov A, Palme K. Regulation of polar auxin transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis vascular tissue. Science. 1998;282:2226–2230. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrasek J, Mravec J, Bouchard R, Blakeslee JJ, Abas M, Seifertova D, Wisniewska J, Tadele Z, Kubes M, Covanova M, Dhonukshe P, Skupa P, Benkova E, Perry L, Krecek P, Lee OR, Fink GR, Geisler M, Murphy AS, Luschnig C, Zazimalova E, Friml J. PIN proteins ferform a rate-limiting function in cellular auxin efflux. Science. 2006;312:914–918. doi: 10.1126/science.1123542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Pischke MS, Mahonen AP, Miyawaki K, Hashimoto Y, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Shinozaki K, Kato T, Tabata S, Helariutta Y, Sussman MR, Kakimoto T. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8821–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402887101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita-Tsujimura K, Kakimoto T. Cytokinin receptors in sporophytes are essential for male and female functions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:66–71. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.13999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Li X, Cui D, Wu L, Parkin I, Gruber MY. A new dominant Arabidopsis transparent testa mutant, sk21-D, and modulation of seed flavonoid biosynthesis by KAN4. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:979–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky MF, Ma H, Bowman JL, Drews GN, Feldmann KA, Meyerowitz EM. The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature. 1990;346:35–39. doi: 10.1038/346035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack T, Brockman LL, Meyerowitz EM. The homeotic gene APETALA3 of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a MADS box and is expressed in petals and stamens. Cell. 1992;68:683–697. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parinov S, Sevugan M, Ye D, Yang WC, Kumaran M, Sundaresan V. Analysis of flanking sequences from dissociation insertion lines: a database for reverse genetics in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2263–2270. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan V, Springer P, Volpe T, Haward S, Jones JD, Dean C, Ma H, Martienssen R. Patterns of gene action in plant development revealed by enhancer trap and gene trap transposable elements. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1797–1810. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions RA, Zambryski PC. Arabidopsis gynoecium structure in the wild and in ettin mutants. Development. 1995;121:1519–1532. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross-Hardt R, Lenhard M, Laux T. WUSCHEL signaling functions in interregional communication during Arabidopsis ovule development. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1129–1138. doi: 10.1101/gad.225202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truernit E, Bauby H, Dubreucq B, Grandjean O, Runions J, Barthelemy J, Palauqui JC. High-resolution whole-mount imaging of three-dimensional tissue organization and gene expression enables the study of phloem development and structure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1494–1503. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]