Abstract

Most patients with insults to the spinal cord or central nervous system suffer from excruciating, unrelenting, chronic pain that is largely resistant to treatment. This condition affects a large percentage of spinal cord injury patients, and numerous patients with multiple sclerosis, stroke and other conditions. Despite the recent advances in basic science and clinical research the pathophysiological mechanisms of pain following spinal cord injury remain unknown. Here we describe a novel mechanism of loss of inhibition within the thalamus that may predispose for the development of this chronic pain and discuss a potential treatment that may restore inhibition and ameliorate pain.

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, the number of people in the United States who suffer from spinal cord injury is approximately 259,000,1 with some studies reporting an even higher incidence (1,275,000 individuals).2 It is estimated that the number of individuals suffering from SCI increases by approximately 12,000 new cases every year with many of these injuries occuring between the ages of 16 and 30.1 Injury to the spinal cord is devastating and leads to catastrophic consequences such as decreased ability to walk or move,3 loss of sexual function,4 diminished ability to control bladder or bowel function5 and the development of debilitating pain.6

Pain resulting from spinal cord injury is referred to as central pain which is “pain initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the central nervous system”.7 The pain is most often steady and unrelenting, and has been described “as if knives heated in Hell‘s hottest corner were tearing me to pieces.”8 Central pain can be initiated by a variety of conditions and insults at any level of the spinal cord and the brain. The most common conditions are spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis (MS) and cerebrovascular lesions (stroke). The prevalence of pain in these conditions is alarmingly high: as many as 60–80% of spinal cord injury patients experience pain9–15 with at least 1/3 of the patients reporting severe pain.16 In MS patients almost 30% develop chronic neuropathic pain and in stroke patients the prevalence is as high as 10%.6,17,18 Because spinal cord injury is the most common etiology for central pain, this chapter is focused on pain resulting from spinal cord injury.

PAIN CHARACTERISTICS FOLLOWING SPINAL CORD INJURY

Several distinct types of pain can develop following spinal cord injury. One that can be observed in patients with spinal cord injury is musculoskeletal pain occurring due to muscle spasm, or due to overuse or abnormal use of structures such as the arms or the shoulders.19 The pain is often dull, aching and is relieved by physical therapy, exercise, non steroidal anti-inflammatory treatments (NSAIDs) and opiods. Another type of pain is visceral pain in the abdomen, which is dull, cramping and located in a region with intact innervation and is thought to occur due to normal peripheral inputs from sympathetic or vagus nerve.20,21 Both of these types of pain, musculoskeletal and visceral, have delayed onset after injury and are classified as nociceptive pains because they arise from stimulation or activity of peripheral nociceptive afferents.22

However, the most debilitating pain and puzzling is the presence of sharp, shooting, and burning neuropathic pain. This pain is spontaneous in the majority of patients but can manifest both as an increased pain with noxious stimulation (hyperalgesia) and as pain in response to previously innocuous stimuli (allodynia).18,23–25 Neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury can be classified into three categories based on the location of the painful region relative to the location of the spinal injury: (1) Below-level pain: The pain is diffuse and located in areas with interrupted sensory innervation below the level of spinal injury; (2) At-level pain at the border of normal and interrupted sensory innervation and distributed within a band of 2 to 4 segments surrounding the level of injury and (3) Above-level pain in regions with preserved sensory inputs above the level of injury. Neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury is largely resistant to conventional pharmacologic treatments26 and to this date the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development of central neuropathic pain remain a mystery and effective treatments are lacking. Therefore, the study of the mechanisms of central pain and the development of effective treatments and animal models that recapitulate the clinical characteristics of this condition are needed.

ANIMAL MODELS OF SPINAL CORD INJURY PAIN

Several animal models have been developed to study spinal cord injury pain (Table 1). In all of these models, the location, the extent and the means to produce injury vary. Some use controlled spinal contusions to mimic clinical traumatic injuries.27–29 Others have used ischemic lesions,30,31 or a neurotoxic chemical injection into the spinal cord,32,33 whereas some have used cuts to sever the spinal cord (hemisection),34,35 or localized regions in the spinal cord (cordotomy).36,37 Most of these models rely on measures of evoked pain and hypersensitivity, such as mechanical and thermal withdrawal thresholds. However, they commonly do not attempt to quantify spontaneous pain, which is the single most common and debilitating complaint from spinal cord injury patients.15,16,38

Table 1.

Animal models of spinal cord injury pain

| Animal Model | Animal Species | Method | Behavioral Findings | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterolateral cut model36,37,107 | Monkey, rat | Anterolateral cut of the spinal cord to interrupt the STT | Over grooming and below-level bilateral hyperalgesia to electrical and mechanical stimulation |

|

| Contusion model27–29,108 | Rat | Dropping of a weight on the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord | Eighty percent of animals develop at-level and above-level mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia |

|

| Hemisection model34,35 | Rat | Unilateral cut of the spinal cord at the mid thoracic level | All animals develop bilateral below- and above-level bilateral mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia |

|

| Quisqualate model32,33 | Rat | Injection of neurotoxic chemicals into the dorsal horn | Fifty percent of the animals develop over grooming in areas somatotopically related to the lesion and at- and below-level mechanical hyperalgesia |

|

| Ischemia model30,31 | Rat | Injecting a photo sensitive dye through circulation and using a focused laser beam to region of the spinal cord. The interaction of the laser beam with the photosensitive dye results in a lesion in the gray matter of the spinal cord | Forty four percent of animals develop at-level and below level mechanical allodynia. None of the animals develop thermal hyperalgesia |

|

| Discrete avulsion of dorsal roots109 | Rat | Unilateral avulsion of T13 and L1 dorsal root damaging Lissauer’s tract, dorsal horn and dorsal column | Bilateral below-level mechanical hyperalgesia |

|

| Electrolytic lesions model39,40,82 | Rat | Localized electrolytic lesions of the anterolateral quadrant of the spinal cord | Ninety four percent of animals develop bilateral below- and above-level mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia |

|

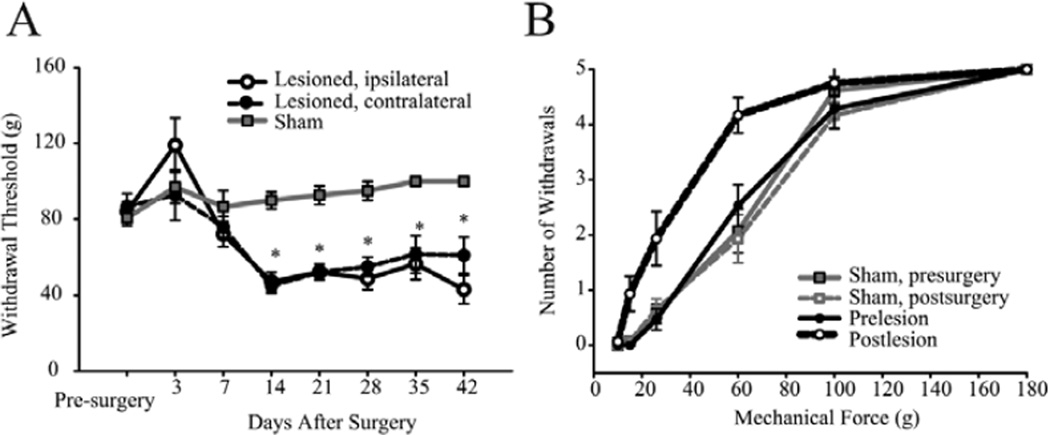

We have demonstrated that localized electrolytic lesions in the anterolateral quadrant of the spinal cord result in consistent, long lasting below- and above-level mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (Fig. 1).39,40 Immediately following the spinal lesion, hindpaw withdrawal thresholds to mechanical stimulation of the dorsal paw surface transiently increased (hypoalgesia). Subsequently, significant reductions in thresholds (hyperalgesia) were evident bilaterally by 14 days post-lesion. The reduction in withdrawal threshold persisted for at least 42 weeks. Sham surgery had no effect on mechanical withdrawal thresholds on either the ipsilateral or the contralateral hindpaw.39 We also tested these animals using a modification of a conditioned place preference paradigm described by King et al,41 to assay if animals with spinal lesions exhibit signs of spontaneous pain. We placed the animals in a custom built, automated 2-chamber box. The walls of one chamber were white with horizontal black stripes and the walls of the other chamber were white with vertical black stripes. Rats with spinal cord lesions and sham-operated controls were habituated to the conditioned place preference box for 3 days and were permitted to move freely between the two chambers for 30 minutes. After habituation, and before conditioning, the time spent in each chamber was recorded to determine each rat’s preference. Rats then underwent a 3-day conditioning phase in which they received either an intraventricular microinjection of vehicle (control: 5 µl saline followed by 10 µl saline flush); or an intraventricular microinjection of clonidine, an alpha 2-adrenergic agonist (analgesic: 5 µl [2 mg/mL] followed by 10 µl saline flush). Animals with spinal cord lesions, but not control animals, develop a significant preference to the analgesic-paired chamber compared to the saline-paired chamber (unpublished data). These findings are consistent with King et al,41 and suggest that animals with spinal cord lesion exhibit signs of tonic pain.

Figure 1.

Behavioral assessment of spinal-lesioned and sham-operated animals. A) hindpaw (dorsal surface) mechanical withdrawal thresholds decrease over time and hyperalgesia develops bilaterally after spinal lesions. B) stimulus-response curves collected before and 14 days after surgery. All values means ± SE; *, statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.39 Reproduced from Masri R, et al. J Neurophysiol 2009; 102:181–191;39 with permission of the American Physiological Society.

MECHANISMS OF SPINAL CORD INJURY PAIN

Since the first published description of central pain, over 120 years ago,42,43 numerous hypotheses have been proposed to explain its pathophysiology.6,18,44,45 Many were disproved with time, and many remain controversial. Fortunately, despite the clinical variability in presentation and variability in size, location and causes of spinal cord injury, there is general agreement on a number of pathophysiological factors:

Many of the earliest reported cases of central pain are based on pain caused by damage or injury to the thalamus.43,46,47 As a result, thalamic abnormalities were thought to be required for development of pain and the condition was referred to for decades by the misleading term “thalamic pain”. Research since that time has established that central pain can result from damage to any structure along the afferent spinothalamocortical pathway that conveys pain and temperature information.18,48–52 This pathway includes: The spinothalamic tract (STT) in the spinal cord and brainstem; thalamic nuclei that receive STT input, including the posterior thalamus (PO), the mediodorsal thalamus (MD) and the ventroposterior complex (VP); the internal capsule; and cortical areas such as the primary (S1) and second (S2) somatosensory cortices.53,54 Damage to the spinothalamocortical pathway is, in fact, necessary for central pain development. There are no documented cases of pain resulting from central nervous system lesions that spare it, such as lesions involving only the dorsal column-medial lemniscal pathway.44 Consistent with an obligatory role for the STT is the finding that essentially all central pain patients have altered pain and temperature sensation, while abnormalities of tactile sensation occur in only a subset of patients.18,49,55 Unfortunately, the consensus appears to end there as there are several hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of central pain.

Most of our knowledge regarding molecular, cellular and physiological changes following spinal cord injury comes from studies performed in animal models of spinal cord injury pain. Hyperalgesia and pain following spinal cord injury can result from maladaptive plastic changes throughout the neural axis. In the spinal cord there are massive changes following injury that include: Ischemia, necrosis, deafferentation, re-organization and sprouting in primary afferents, the activation of astrocytes and glia and the release of inflammatory mediators and neurotoxic excitatory amino acids in the extracellular space.35,56–58

These changes have far reaching consequences that compromise the normal function of not only the surrounding local neurons but also their distant targets within the central nervous system. Indeed, the delayed onset of pain and the diffuse localization of painful symptoms suggest that the pathophysiology does not reflect only direct effects at the denervated spinal segments. Rather, these features strongly suggest the occurrence of maladaptive plasticity in supraspinal structures at which inputs from various body parts converge. Consistent with this notion, it has been shown repeatedly that spinal cord injury is associated with increased activity, increased spike bursts and changes in glial activation in the thalamus.40,59–61 However, the mechanism by which these central maladaptive changes occur requires more study.

One hypothesis that remains in favor, almost a century since it was first formulated, is that central pain results from abnormally suppressed inhibition in the thalamus47 however, the site of operation of this dis-inhibition remains unknown.18,44 For example, it has been argued that the medial lemniscal pathway normally inhibits the spinothalamic system, and that this inhibition is suppressed in central pain. It has been proposed that either descending cortical inputs or ascending spinal inputs to the thalamus are involved in this dis-inhibition.47,62 A more recent elaboration of the Head and Holmes hypothesis47 posits that the disinhibition results from a loss of the discriminative thermosensory representation in the central nervous system.63 This “thermosensory disinhibition hypothesis” assumes that pain is relayed from the spinal cord through independent thalamic pain/temperature nuclei that serve as specific relays in the ascending pain system. However, this viewpoint is controversial and remains unresolved.

Loss of inhibition has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of central pain and is thought to alter the firing properties of thalamic neurons, rendering them more likely to produce spontaneous and evoked bursts of action potentials.64,65 However, some have argued that the incidence and properties of these bursts in central pain do not differ significantly than in controls.66 In sum, remaining unknown are the mechanisms for the engagement of inhibition, the source of this inhibition, and the specific nuclei affected.

ABNORMAL INHIBITION IN THE THALAMUS

A unique source of inhibition to the thalamus is the aptly named zona incerta (ZI) or “zone of uncertainty”. The ZI receives nociceptive inputs through the STT,67,68 and has been implicated in a variety of pain related functions.69,70 A striking feature of ZI is its target specificity: In all sensory systems it provides inhibitory inputs exclusively to “higher-order” thalamic nuclei (e.g., posterior nucleus in the somatosensory system and the inferior pulvinar in the visual system) and avoids first-order thalamic nuclei (e.g., ventroposterior in the somatosensory system and the lateral geniculate in the visual system).71,72

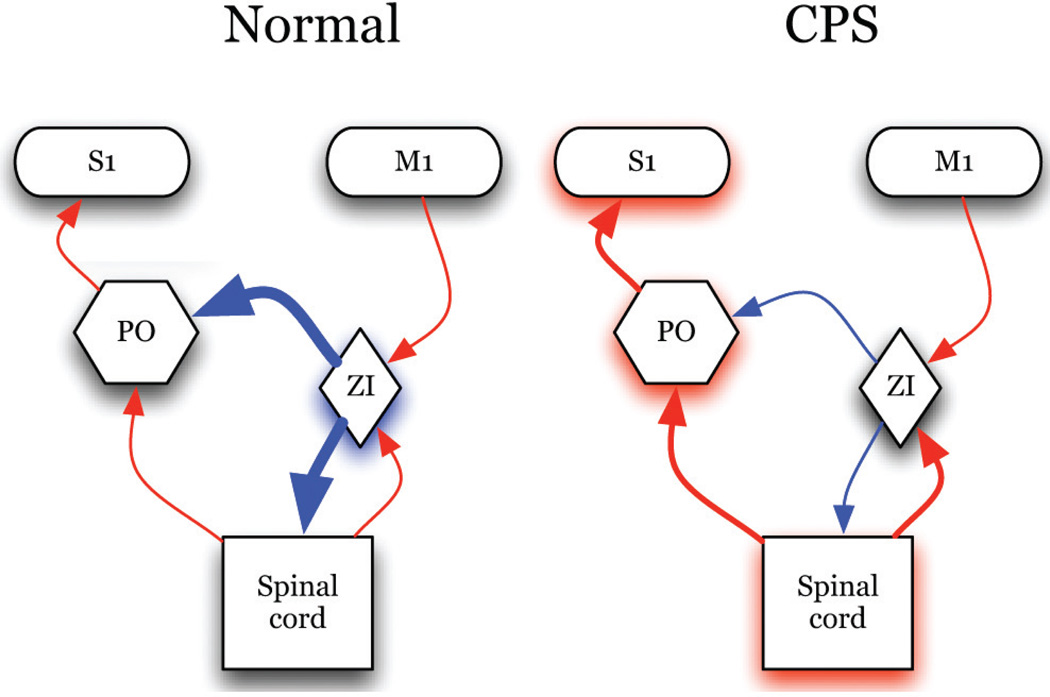

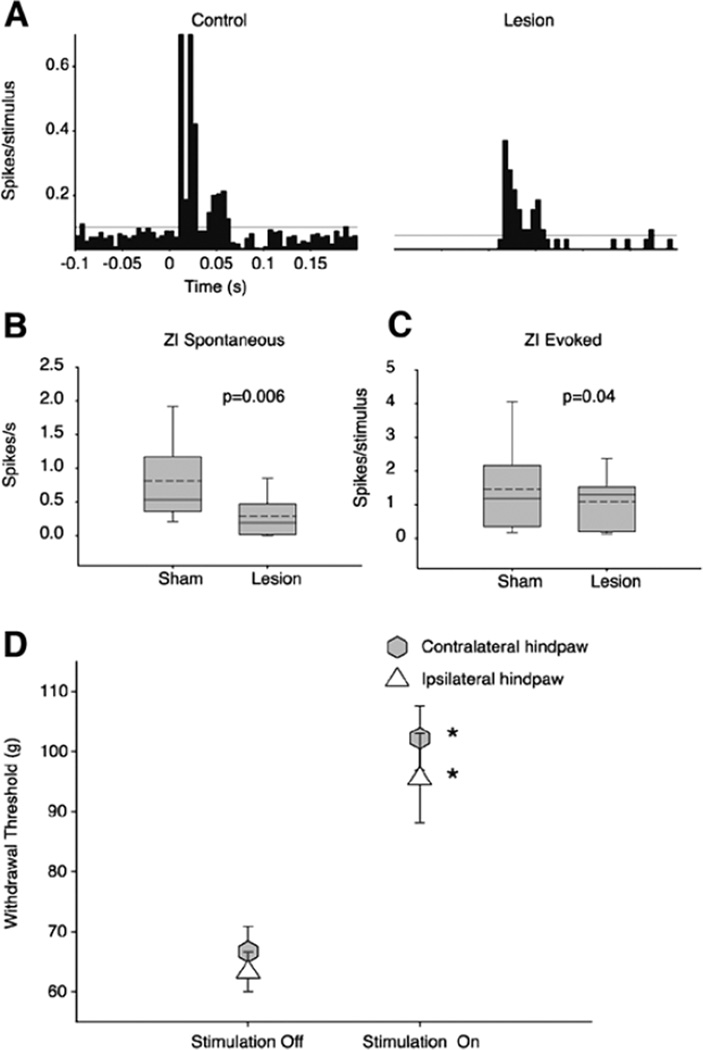

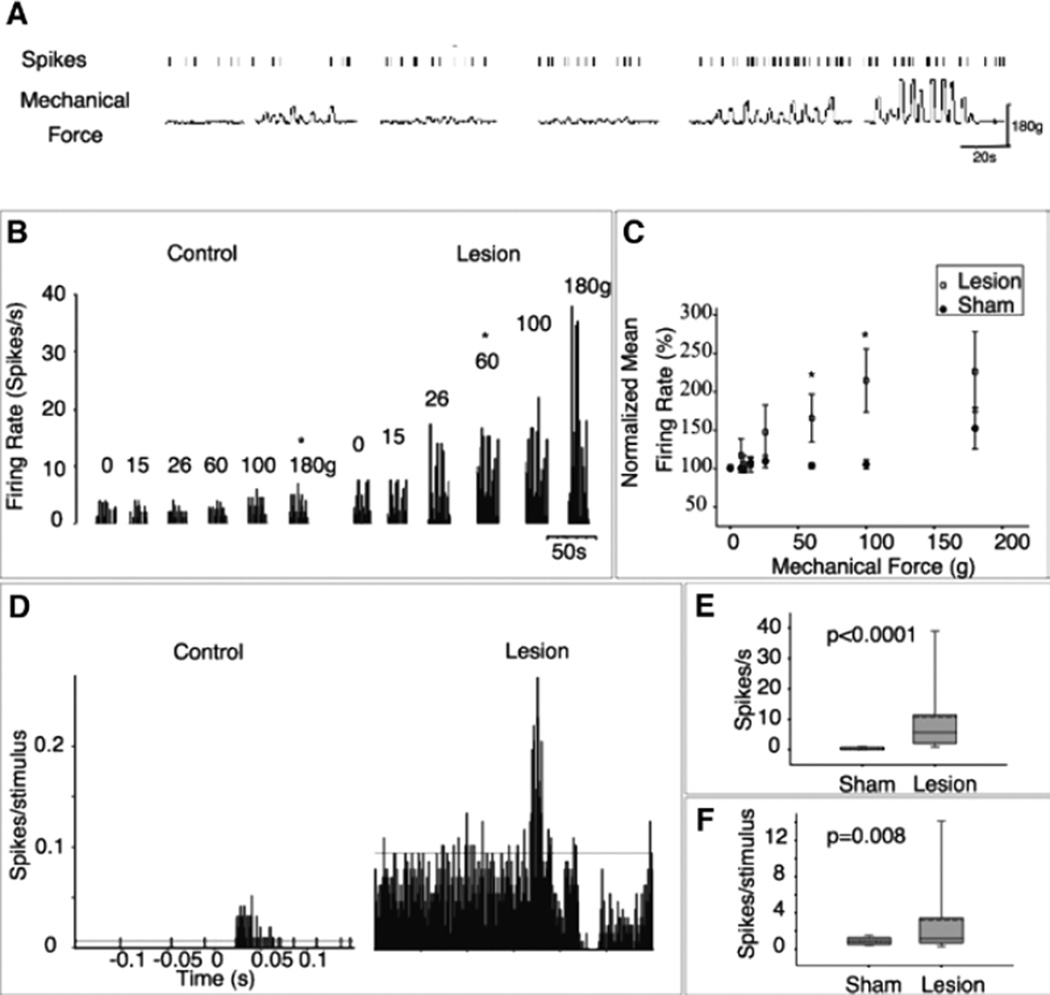

ZI sends a dense GABAergic projection upon the posterior nucleus of the thalamus (PO),71,73 a nucleus critically involved in nociceptive processing.74–77 ZI exerts potent feed-forward and tonic inhibition to PO neurons,78,79 also see ref. 80. Recently, we demonstrated that spontaneous firing rates and somatosensory evoked responses of ZI neurons are lower in animals with spinal cord injury compared to sham-operated controls.39 These findings led us to hypothesize that abnormalities in ZI are casually related to the development of hyperalgesia in animals with spinal cord lesions (Fig. 2). Indeed, and consistent with this hypothesis, electrical stimulation of ZI ameliorates the hyperalgesia in rats with spinal cord lesions.81 The suppressed activity of ZI is associated with a robust enhanced spontaneous and evoked activity in PO (Fig. 3)39 and S1.82 In PO, neurons recorded from animals with hyperalgesia exhibit a 30-fold increase in spontaneous firing rates and significantly greater responses to noxious and innocuous stimuli applied to the hindpaw (Fig. 4). PO neurons respond at the same mechanical threshold that elicit hindpaw withdrawal in animals with spinal cord lesions. Further, the changes in PO activity are not associated with increased afferent drive from spinal inputs.39 These findings led us to conclude that ZI plays an important role in regulating nociceptive transmission from PO to S1 and that abnormalities in ZI are associated with hyperalgesia seen in animals with spinal cord lesions.

Figure 2.

Schematic of our overarching hypothesis: In normal conditions, nociceptive transmission through PO is regulated by powerful inhibition from ZI. In spinal cord injury pain, ZI activity is suppressed and activity in PO is enhanced. MCS enhances activity of ZI and restores inhibition in the thalamus and spinal cord. (Blue represents inhibitory inputs; red: Excitatory Inputs; line thickness represents connection strength).

Figure 3.

Suppressed activity of ZI in animals with spinal cord injury. A) Comparison of activity recorded from a ZI neuron in a sham-operated rat (control) with activity recorded from a rat with a spinal lesion and behaviorally confirmed hyperalgesia. In the neuron recorded from the spinal-lesioned rat the spontaneous firing rate (1.6 Hz) is noticeably lower than in the neuron from the sham-operated rat (12 Hz). The magnitude of evoked responses in the spinal-lesioned rat (0.04 spikes/stimulus) is also markedly lower than in the sham-operated control (1.5 spikes/stimulus). B) As a group ZI neurons from spinal-lesioned rats have significantly lower spontaneous firing rates (0.29 ± 0.28 Hz vs. 0.80 ± 0.70 Hz in shams, P = 0.006), and C) Lower somatosensory evoked responses (1.0 ± 0.7 vs. 1.4 ± 1.3 spikes/stimulus in shams, P = 0.04). D) To test if suppressed activity in ZI is causally responsible for the mechanical hyperalgesia in animals with spinal cord injury, we stimulated ZI using chronically implanted stimulation electrodes. When we applied mechanical stimuli while stimulating ZI (intensity: 25 µA, frequency: 50 Hz, pulse duration: 300 µs), withdrawal thresholds were significantly increased, and typically returned to prelesion levels. ZI stimulation reversed the hyperalgesia in one or both of the hindpaws (range: 0–80% increase in threshold of hindpaw ipsilateral to the lesion, 25–93% increase contralaterally; P < 0.05, MWU).39 Reproduced from Masri R, et al. J Neurophysiol 2009; 102:181–191;39 with permission of the American Physiological Society.

Figure 4.

Enhanced activity of PO in animals with spinal cord injury. A) Representative example of responses recorded from a PO neuron in an animal with spinal cord lesion and confirmed hyperalgesia. Time stamps of action potentials (upper trace) recorded during spontaneous activity, and during application mechanical forces (lower trace) to the dorsal surface of the hindpaw, using an electronic anesthesiometer. B) In a PO neuron from a sham-operated control, spontaneous firing rate is low, and responses significantly exceed this spontaneous activity level only when strong stimuli (>180 g) are applied. In a neuron from the spinal-lesioned animal with hyperalgesia, spontaneous activity is higher, and electrophysiological thresholds are considerably lower (60 g). C) Group data showing that the activity of PO neurons is significantly higher in animals with spinal cord injury in response to mechanical hindpaw stimulation. D) The activity of PO neurons in animals with spinal cord injury is also higher in response to innocuous stimulation. PSTHs (bin = 1 msec) computed for PO neurons recorded from a sham-operated and a spinal-lesioned animal. Spontaneous activity (E) and evoked activity (F) are enhanced in PO neurons recorded from spinal-lesioned animals. *, statistically significant difference, P < 0.05.39 Reproduced from Masri R, et al. J Neurophysiol 2009; 102:181–191;39 with permission of the American Physiological Society.

Another source of inhibition in the thalamus that can be affected after spinal cord injury is the anterior pretectal nucleus (APT). The APT also sends dense GABAergic inputs to higher-order thalamic nuclei and like ZI, has been shown to regulate the activity of PO neurons.83 The APT receives nociceptive inputs through the STT,68,84,85 and have been implicated in a variety of pain-related functions.69,70 Indeed activity in the APT of animals with confirmed hyperalgesia following spinal cord injury is abnormal. The firing rate of APT neurons is increased compared to sham-operated controls. This increase is due to a selective increase in firing of tonic neurons that project to and inhibit ZI and an increase in bursts of fast bursting and slow rhythmic neurons. These findings suggest that APT regulates ZI inputs to PO and that enhanced APT activity contributes to the hyperalgesia observed in animals following spinal cord injury.86

In the rat PO there are no GABAergic interneurons87 and therefore, all GABAergic inhibition is mediated by extrinsic afferents. Another important source of these afferents in addition to ZI and APT is the GABAergic reticular nucleus of the thalamus (TRN), which has been hypothesized to play a role in central pain.88 However, anatomical and electrophysiological evidence argues against a role for TRN in the pathophysiology of central pain. TRN does not receive ascending sensory inputs, and its major source of excitatory input is from somatosensory cortex.89 Further, GABAergic terminals in PO that originate from ZI differ from those of TRN origin by their larger size, the presence of multiple release sites, and multiple filamentous contacts, all features suggesting that ZI exerts significantly more potent inhibition upon PO.71,90 Moreover, responses evoked with innocuous stimuli in ventroposterior thalamus—nuclei that receive inhibition exclusively from TRN—are unaffected by spinal lesions.39

These findings describe a novel system for the regulation of nociceptive processing in the thalamus, the APT/incerto-thalamic system.39,86 Abnormalities in this system are causally related to maladaptive plasticity following spinal cord injury and manipulation of this system may prove effective in ameliorating chronic neuropathic pain.

POTENTIAL TREATMENTS FOR SPINAL CORD INJURY PAIN

Traditionally treatment options for patients suffering from spinal cord injury pain is limited to either pharmacological treatments or nonpharmacologic approaches or a combination of both. A variety of medications have been used for the treatment of spinal cord injury pain including NSAIDS, opioids, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, NMDA receptor antagonists, alpha 2-adrenergic agonists and GABA-receptor agonists. However, these medications are rarely consistently effective, and treatment protocols that produce complete pain relief have never been established.26,91

Nonpharmacologic approaches include electrical stimulation of various structures in the central nervous system such as the spinal cord, the internal capsule,92 the periaqueductal gray-periventricular gray complex,93 the somatosensory cortex and the thalamus.94

A potentially effective nonpharmachologic treatment that has been advocated for patients with chronic neuropathic pain is electrical stimulation of the motor cortex. This method was introduced in 1991 for the treatment of central pain95 and since then its use has been extended for the treatment of several other neuropathic pain conditions.96–98 Motor cortex stimulation is more effective and more advantageous than stimulating other central nervous system structures because of the low occurrence of complications,99 the lower propensity to cause seizures,100 and the ability to apply it non-invasively using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.101

Pain relief occurs almost immediately after onset of motor cortex stimulation in approximately 50% of patients and persists after the stimulation has stopped.102,103 However, mixed outcomes and varied success rates are observed.104 The lack of well controlled studies, the diverse approaches employed and lack of understanding of how motor cortex stimulation results in pain relief have contributed to the mixed outcomes and reduced the enthusiasm for this potentially effective treatment.

Recently, we used our animal model of spinal cord injury pain to study the effective parameters of motor cortex stimulation.81 We systematically tested a large parameter space of stimulus conditions, an advantage not available in human studies. Motor cortex stimulation reduced hyperalgesia in a manner that is dependent on stimulation parameters and protocol used. Stimulation at an intensity of 50 µA and frequency of 50 Hz for 30 minutes was most effective at reducing mechanical hyperalgesia in rats bilaterally81 (Fig. 5).

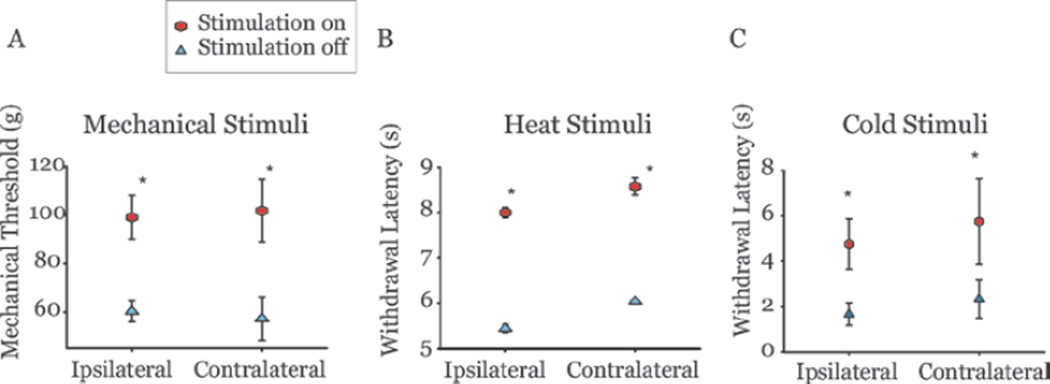

Figure 5.

Motor cortex stimulation relieves hyperalgesia in animals with spinal cord lesions. A) Mechanical thresholds (tested on the dorsal surface) of animals with confirmed hyperalgesia after spinal cord lesions increased following motor cortex stimulation (50 µA, 50 Hz, for 30 minutes) on both hindpaws. Thermal withdrawal latencies to heat (B) and cold (C) stimuli were also increased in the same animals after motor cortex stimulation. Ipsilateral or contralateral are relative to the site of spinal lesion. Error bars = SEM.

Using these effective stimulation parameters we were able to further test mechanisms of pain relief produced by motor cortex stimulation. We discussed above evidence (Fig. 3) that activity of ZI is suppressed in conditions of spinal cord injury pain. The ZI receives dense projections from prefrontal motor area including the motor cortex105,106 and, therefore, reduction in hyperalgesia following motor cortex stimulation could be due to enhanced activity in ZI. To test this notion, we inactivated ZI with lidocaine injections in animals with spinal cord injury and confirmed hyperaglesia, and then stimulated the motor cortex. Administration of lidocaine but not saline into ZI reversibly blocked the effects of motor cortex stimulation.81

These results combined with our earlier findings,39 identify the ZI as a source of inhibition that can be manipulated to produce pain relief, and describe a novel system that affects nociceptive transmission within the thalamus through corticothalamic interactions. Identifying the mechanisms involved in the short- and long-term consequences of motor cortex stimulation will shift current research and clinical practice paradigms and pave the way towards the development of molecular, pharmacologic and physiologic methods for permanent pain relief that target these structures.

CONCLUSION

Spinal cord injury pain is a debilitating condition that affects a large number of patients with a primary lesion or dysfunction in the central nervous system. Despite its discovery over a century ago, the pathophysiological processes underlying the development and maintenance of chronic neuropathic pain are poorly understood. Pain can result from suppressed inhibitory inputs from ZI and APT. The suppressed inhibitory inputs will lead to enhanced activity in the PO, S1 and any thalamic nucleus that is regulated by ZI/APT. Manipulations that enhance activity in ZI/APT and rescue inhibition may prove effective in the treatment of spinal cord injury pain.

REFERENCES

- 1.National spinal cord injury statistical center. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753637. Https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christopher & dana reeve foundation. Paralysis statistics. Http://www.christopherreeve.org/site/c.mtkzkgmwkwg/b.5184189/k.5587/paralysis_facts__figures.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Hedel HJ, Dietz V. Rehabilitation of locomotion after spinal cord injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28(1):123–134. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson C, Mcbride K, Konnyu K, et al. Sexual health outcome measures for individuals with a spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(5):320–324. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persu C, Caun V, Dragomiriteanu I, et al. Urological management of the patient with traumatic spinal cord injury. J Med Life. 2009;2(3):296–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yezierski RP. Pain following spinal cord injury: Pathophysiology and central mechanisms. Prog Brain Res. 2000;129:429–449. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)29033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes G. Pain of central origin. In: Osler W, editor. Contributions to Medical and Biological Research. New York: Hoeber; 1919. pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddall P, Mcclelland J, Rutkowski S, et al. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain. 2003;103(3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolsey R. Chronic pain following spinal cord injury. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1986;9(3–4):39–41. doi: 10.1080/01952307.1986.11719622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nepomuceno C, Fine P, Richards J, et al. Pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;60(12):605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamid S, Chia J, Kohli A, et al. Chronic pain in spinal cord injury: Comparison between inpatients and outpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985;66(11):777–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levi R, Hultling C, Nash M, et al. The stockholm spinal cord injury study: 1. Medical problems in a regional sci population. Paraplegia. 1995;33(6):308–315. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New P, Lim T, Hill S, et al. A survey of pain during rehabilitation after acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35(10):658–663. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stormer S, Gerner H, Gruninger W, et al. Chronic pain/dysaesthesiae in spinal cord injury patients: Results of a multicentre study. Spinal Cord. 1997;35(7):446–455. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonica JJ. Introduction: semantic, epidemiologic, and educational issues. In: Casey KL, editor. Pain and central nervous system disease: the central pain syndrome. New York: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonica JJ. History of pain concepts and pain therapy. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58(3):191–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boivie J. Central Pain. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, editors. Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 1057–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalyan M, Cardenas D, Gerard B. Upper extremity pain after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1999;37(3):191–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn RA. Functional capacity of the isolated human spinal cord. Brain. 1950;73(1):1–51. doi: 10.1093/brain/73.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komisaruk B, Gerdes C, Whipple B. ‘Complete’ spinal cord injury does not block perceptual responses to genital self-stimulation in women. Arch Neurol. 1997;54(12):1513–1520. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddall PJ, Yezierski RP, Loeser JD. Taxonomy and epidemiology of spinal cord injury pain. In: Yezierski RP, Burchiel KJ, editors. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: IASP Press; 2002. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenspan JD, Ohara S, Sarlani E, et al. Allodynia in patients with post-stroke central pain (cpsp) studied by statistical quantitative sensory testing within individuals. Pain. 2004;109(3):357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tasker RR. Meralgia paresthetica. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(1):168. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0168a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baliki M, Geha P, Apkarian A. Spontaneous pain and brain activity in neuropathic pain: Functional mri and pharmacologic functional mri studies. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11(3):171–177. doi: 10.1007/s11916-007-0187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baastrup C, Finnerup N. Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(6):455–475. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheff S, Rabchevsky A, Fugaccia I, et al. Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: Characterization of a force-defined injury device. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20(2):179–193. doi: 10.1089/08977150360547099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulsebosch C, Hains B, Crown E, et al. Mechanisms of chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon Y, Dong H, Arends J, et al. Mechanical and cold allodynia in a rat spinal cord contusion model. Somatosens Mot Res. 2004;21(1):25–31. doi: 10.1080/0899022042000201272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hao J, Xu XJ, Aldskogius H, et al. Allodynia-like effects in rat after ischaemic spinal cord injury photochemically induced by laser irradiation. Pain. 1991;45(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao J, Xu XJ. Treatment of a chronic allodynia-like response in spinally injured rats: Effects of systemically administered excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists. Pain. 1996;66(2–3):279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yezierski RP, Liu S, Ruenes GL, et al. Excitotoxic spinal cord injury: Behavioral and morphological characteristics of a central pain model. Pain. 1998;75(1):141–155. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caudle R, Perez F, King C, et al. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit expression and phosphorylation following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;349(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00700-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen M, Everhart A, Pickelman J, et al. Mechanical and thermal allodynia in chronic central pain following spinal cord injury. Pain. 1996;68(1):97–107. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christensen M, Hulsebosch C. Chronic central pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14(8):517–537. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vierck CJ, Greenspan J, Ritz L. Long-term changes in purposive and reflexive responses to nociceptive stimulation following anterolateral chordotomy. J Neurosci. 1990;10(7):2077–2095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02077.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vierckjr C, Light A. Effects of combined hemotoxic and anterolateral spinal lesions on nociceptive sensitivity. Pain. 1999;83(3):447–457. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finnerup NB, Johannesen IL, Sindrup SH, et al. Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: A postal survey. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(5):256–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masri R, Quiton R, Lucas J, et al. Zona incerta: A role in central pain. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102(1):181–191. doi: 10.1152/jn.00152.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Thompson S. Maladaptive homeostatic plasticity in a rodent model of central pain syndrome: Thalamic hyperexcitability after spinothalamic tract lesions. J Neurosci. 2008;28(46):11959–11969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3296-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King T, Vera-Portocarrero L, Gutierrez T, et al. Unmasking the tonic-aversive state in neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(11):1364–1366. doi: 10.1038/nn.2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greiff F. Zur localisation der hemichorea. Archiv fur Psychologie und Nervenkrankheiten. 1883;14:598–624. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edinger L. Giebt es central antstehender schmerzen. Deutche Zeitschrift fur Nervenheilkunde. 1891;1:262–282. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Central Pain Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fregni F, Freedman S, Pascual-Leone A. Recent advances in the treatment of chronic pain with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):188–191. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dejerine J, Roussy G. Le syndrome thalamique. Rev Neurol. 1906;14:521–532. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Head H, Holmes G. Sensory disturbances from cerebral lesions. Brain. 1911;34:102–254. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmahmann J, Leifer D. Parietal pseudothalamic pain syndrome. Clinical features and anatomic correlates. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(10):1032–1037. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530340048017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowsher D. Central pain. Pain Reviews. 1995;2:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finnerup N, Johannesen I, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A, et al. Sensory function in spinal cord injury patients with and without central pain. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 1):57–70. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macgowan D, Janal M, Clark W, et al. Central poststroke pain and wallenberg’s lateral medullary infarction: Frequency, character, and determinants in 63 patients. Neurology. 1997;49(1):120–125. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Greenspan J, Coghill R, et al. Lesions limited to the human thalamic principal somatosensory nucleus (ventral caudal) are associated with loss of cold sensations and central pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27(18):4995–5004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0716-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dostrovsky JO. Ascending projection systems. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, editors. Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones EG. The Thalamus. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beric A. Post-spinal cord injury pain states. Pain. 1997;72(3):295–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu D, Thangnipon W, Mcadoo D. Excitatory amino acids rise to toxic levels upon impact injury to the rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1991;547(2):344–348. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90984-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christensen M, Hulsebosch C. Spinal cord injury and anti-ngf treatment results in changes in cgrp density and distribution in the dorsal horn in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;147(2):463–475. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yezierski RP. Pathophysiology and animal models of spinal cord injury pain. In: Yezierski RP, Burchiel KJ, editors. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: IASP Press; 2002. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lenz F, Tasker R, Dostrovsky J, et al. Abnormal single-unit activity recorded in the somatosensory thalamus of a quadriplegic patient with central pain. Pain. 1987;31(2):225–236. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lenz F, Kwan H, Dostrovsky J, et al. Characteristics of the bursting pattern of action potentials that occurs in the thalamus of patients with central pain. Brain Res. 1989;496(1–2):357–360. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao P, Waxman S, Hains B. Modulation of thalamic nociceptive processing after spinal cord injury through remote activation of thalamic microglia by cysteine cysteine chemokine ligand 21. J Neurosci. 2007;27(33):8893–8902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2209-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foerster O. Die Lactungsbahnen des Schmerzgefuhls und die chirurgische Behandlung der Schmerzzustande. Berlin: Urban and Schwarzenberg; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Craig AD. Mechanisms of thalamic pain. In: Henry JL, Panju A, Yashpal K, editors. Central Neuropathic Pain: Focus on Poststroke Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2007. pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weng H, Lee J, Lenz F, et al. Functional plasticity in primate somatosensory thalamus following chronic lesion of the ventral lateral spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2000;101(2):393–401. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lenz F, Garonzik I, Zirh T, et al. Neuronal activity in the region of the thalamic principal sensory nucleus (ventralis caudalis) in patients with pain following amputations. Neuroscience. 1998;86(4):1065–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dostrovsky JO. The thalamus and human pain. In: Henry JL, Panju A, Yashpal K, editors. Central Neuropathic Pain: Focus on Poststroke Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 2007. pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shammah-Lagnado SJ, Negrao N, Ricardo JA. Afferent connections of the zona incerta: A horseradish peroxidase study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1985;15(1):109–134. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Craig AD. Distribution of trigeminothalamic and spinothalamic lamina I terminations in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2004;477(2):119–148. doi: 10.1002/cne.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Porro CA, Cavazzuti M, Lui F, et al. Independent time courses of supraspinal nociceptive activity and spinally mediated behavior during tonic pain. Pain. 2003;104(1–2):291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yen CT, Fu TC, Chen RC. Distribution of thalamic nociceptive neurons activated from the tail of the rat. Brain Res. 1989;498(1):118–122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bartho P, Freund TF, Acsady L. Selective gabaergic innervation of thalamic nuclei from zona incerta. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16(6):999–1014. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitrofanis J. Some certainty for the “zone of uncertainty”? Exploring the function of the zona incerta. Neuroscience. 2005;130(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Power B, Kolmac C, Mitrofanis J. Evidence for a large projection from the zona incerta to the dorsal thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404(4):554–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Poggio GF, Mountcastle VB. A study of the functional contributions of the lemniscal and spinothalamic systems to somatic sensibility. Central nervous mechanisms in pain. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1960;106:266–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Casey K. Unit analysis of nociceptive mechanisms in the thalamus of the awake squirrel monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1966;29(4):727–750. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Apkarian A, Shi T. Squirrel monkey lateral thalamus. I. Somatic nociresponsive neurons and their relation to spinothalamic terminals. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 2):6779–6795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06779.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang X, Giesler GJ. Response characterstics of spinothalamic tract neurons that project to the posterior thalamus in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93(5):2552–2564. doi: 10.1152/jn.01237.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trageser JC, Keller A. Reducing the uncertainty: Gating of peripheral inputs by zona incerta. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8911–8915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3218-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trageser JC, Burke KA, Masri RM, et al. State-dependent gating of sensory inputs by zona incerta. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1456–1463. doi: 10.1152/jn.00423.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lavallee P, Urbain N, Dufresne C, et al. Feedforward inhibitory control of sensory information in higher-order thalamic nuclei. J Neurosci. 2005;25(33):7489–7498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2301-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lucas JM, Ji Y, Masri R. Motor cortex stimulation reduces hyperalgesia in an animal model of central pain. Pain. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.025. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quiton R, Masri R, Thompson S, et al. Abnormal activity of primary somatosensory cortex in central pain syndrome. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104(3):1717–1725. doi: 10.1152/jn.00161.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bokor H, Frere S, Eyre M, et al. Selective gabaergic control of higher-order thalamic relays. Neuron. 2005;45(6):929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Apkarian A, Hodge C. Primate spinothalamic pathways: Iii. Thalamic terminations of the dorsolateral and ventral spinothalamic pathways. J Comp Neurol. 1989;288(3):493–511. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shaw V, Mitrofanis J. Lamination of spinal cells projecting to the zona incerta of rats. J Neurocytol. 2001;30(8):695–704. doi: 10.1023/a:1016529817118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murray P, Masri R, Keller A. Abnormal anterior pretectal nucleus activity contributes to central pain syndrome. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103(6):3044–3053. doi: 10.1152/jn.01070.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barbaresi P, Spreafico R, Frassoni C, et al. Gabaergic neurons are present in the dorsal column nuclei but not in the ventroposterior complex of rats. Brain Res. 1986;382(2):305–326. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foix C, Thevenard A, Nicolesco M. Algie faciale dórigine bulbo-trigeminale au cours de la syringomyélie. Troubles sympathiques concomitants. Douleur á type cellulaire. Revue Neurologique. 1922;29:990–999. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu X, Jones E. Predominance of corticothalamic synaptic inputs to thalamic reticular nucleus neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;414(1):67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bokor H, Frère SGA, Eyre MD, et al. Selective gabaergic control of higher-order thalamic relays. Neuron. 2005;45(6):929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Finnerup NB, Johannesen IL, Sindrup SH, et al. Pharmacological treatment of spinal cord injury pain. In: Yezierski RP, Burchiel KJ, editors. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: IASP Press; 2002. pp. 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Namba S, Nakao Y, Matsumoto Y, et al. Electrical stimulation of the posterior limb of the internal capsule for treatment of thalamic pain. Appl Neurophysiol. 1984;47(3):137–148. doi: 10.1159/000101214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gybels J, Kupers R. Deep brain stimulation in the treatment of chronic pain in man: Where and why? Neurophysiol Clin. 1990;20(5):389–398. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(05)80206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Namba S, Nishimoto A. Stimulation of internal capsule, thalamic sensory nucleus (vpm) and cerebral cortex inhibited deafferentation hyperactivity provoked after gasserian ganglionectomy in cat. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1988;42:243–247. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-8975-7_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Treatment of thalamic pain by chronic motor cortex stimulation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1991;14(1):131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1991.tb04058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sol J, Casaux J, Roux F, et al. Chronic motor cortex stimulation for phantom limb pain: Correlations between pain relief and functional imaging studies. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2001;77(1–4):172–176. doi: 10.1159/000064616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ebel H, Rust D, Tronnier V, et al. Chronic precentral stimulation in trigeminal neuropathic pain. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138(11):1300–1306. doi: 10.1007/BF01411059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brown J, Pilitsis J. Motor cortex stimulation for central and neuropathic facial pain: A prospective study of 10 patients and observations of enhanced sensory and motor function during stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(2):290–297. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000148905.75845.98. discussion 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Central pain syndrome: Elucidation of genesis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(11):1485–1497. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.11.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bezard E, Boraud T, Nguyen J, et al. Cortical stimulation and epileptic seizure: A study of the potential risk in primates. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(2):346–350. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199908000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang Y, Edwards M, Rounis E, et al. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron. 2005;45(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lima MC, Fregni F. Motor cortex stimulation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Neurology. 2008;70(24):2329–2337. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000314649.38527.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fontaine D, Hamani C, Lozano A. Efficacy and safety of motor cortex stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain: Critical review of the literature. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2009;110(2):251–256. doi: 10.3171/2008.6.17602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cruccu G, Aziz TZ, Garcia-Larrea L, et al. Efns guidelines on neurostimulation therapy for neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(9):952–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Urbain N, Deschenes M. Motor cortex gates vibrissal responses in a thalamocortical projection pathway. Neuron. 2007;56(4):714–725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mitrofanis J, Mikuletic L. Organisation of the cortical projection to the zona incerta of the thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412(1):173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Levitt M, Levitt J. The deafferentation syndrome in monkeys: Dysesthesias of spinal origin. Pain. 1981;10(2):129–147. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(81)90190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Beattie M, Bresnahan J, Komon J, et al. Endogenous repair after spinal cord contusion injuries in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;148(2):453–463. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wieseler J, Ellis AL, Mcfadden A, et al. Below level central pain induced by discrete dorsal spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2010 doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1311. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]